Introduction

The combination of active genes and the interactions between them within a cell generates a gene regulatory network (GRN) that enables a cell to specialize in fulfilling its function. Therefore, an improved understanding of GRNs paves the way to use such information not only as a means to understand the principles of gene regulation but also as a tool to drive cell fate for purposes such as cellular engineering, or to prevent disease outcomes (Badia-i-Mompel et al., 2023). There are several approaches to infer GRNs from omics data (Badia-i-Mompel et al., 2023, McCalla et al., 2023, Mercatelli et al., 2020). These approaches rely on a combination of biological and statistical information to identify pairs of related genes for the construction of GRNs. Approaches such as co-expression network analysis aim to build a network by identifying genes whose expression profiles are correlated. While these approaches systematically examine the genome and as such are hypothesize-free, the retrieved network is undirected due to the symmetrical nature of correlations. Other methods try to resolve this issue by incorporating biological information. Notably, they use data from CHIP-seq and cis-regulatory elements to identify transcription factors that bind to target genes and as such turn the undirected network into a network that its edges indicate causality. The gene regulatory network obtained from such approaches does not cover the interactions among gene products, (i.e. interaction at the level of pathway/biological processes). Furthermore, they assign transcription factors to their target genes based on genomic proximity which could introduce bias in the presence of distal regulatory effects (Badia-i-Mompel et al., 2023, McCalla et al., 2023, Mercatelli et al., 2020). Another factor that limits the practicability of current approaches is that they require access to individual level data which is not always feasible for reasons such as participants privacy or logistical considerations. In this study, I describe a method based on eQTLs that can address the issues described above.

An eQTL or an expression quantitative trait locus is a site on DNA that variation in its sequence impacts the expression of a gene. If an eQTL is located near the gene it acts upon, it is referred to as a cis-eQTL; however, if it is located distant from its gene of origin, sometimes on a different chromosome, it is referred to as a trans-eQTL. Over the past decades, high throughput studies have been developed to map the eQTLs. Results from these studies which basically summarize the magnitudes and the natures of associations between genomic variants (eQTLs) and genes then are considered collectively to investigate the genetics of transcriptome. An insight from these studies is the evidence that trans-eQTLs tend to be tissue specific (Consortium, 2020, Price et al., 2011, Nica and Dermitzakis, 2013). A new development in this field is the advent of statistical methods that can leverage publicly available GWAS summary statistics including eQTLs to investigate the nature of relation between two biological entities (e.g. two genes) (Pasaniuc and Price, 2017, Zhu et al., 2016). A prominent method in this regard is Mendelian randomization (MR) that can not only test the association between two genes, but also differentiate between causation, correlation, and reverse causation (Davey Smith and Hemani, 2014, Zhu et al., 2018); moreover, because MR uses a set of independent SNPs for association testing, the results are immune to the bias that may be introduced by the environmental (non-genetic) factors. Building upon these notions, in this study, I devised a workflow that can complement the previous approaches for constructing tissue-specific GRNs.

Materials and Methods

eQTL Data

Previously, eQTLGen consortium has investigated the genetic architecture of blood gene expression by incorporating eQTL data from 37 datasets, compromising a total of 31,684 blood samples. (Võsa et al., 2021) After processing eQTL data (P<5e-8) from this database, I found trans-eQTLs for 3,628 genes, and cis-eQTLs (P<5e-8) for 15,786 genes (a total of 16,259 genes).

To understand the distribution of eQTLs and account for the linkage disequilibrium (LD) between them for downstream analyses. I generated a list of independent (r2<0.05) eQTLs per gene using the clump algorithm implemented in PLINK (v.1.9) (Chang et al., 2015). In summary, the algorithm takes a list of eQTLs and their P-values, conducts LD pruning, and returns a list of eQTLs in linkage equilibrium and prioritized by P-values. The clump algorithm requires access to a genotype panel to compute LD values. For this purpose, I used a subset of genotype data from the 1000 genomes (phase 3), compromising 503 individuals of European ancestry.

Following the LD pruning, the phenotypic variance (

, proportion of variation in a gene expression) attributed to an eQTL was calculated, as previously described (Park et al., 2010) using the equation:

Where

is the frequency of effect allele and

is its regression coefficient derived from the association model. eQTLGen consortium reported Z-scores instead of regression coefficients. As such, a conversion was made using the equation (Zhu et al., 2016):

To understand the distribution of eQTLs with regard to genes, the ANNOVAR software (version June 2020) (Wang et al., 2010) was used to annotate eQTLs.

Results

General Characteristics of Trans-eQTLs

In the eQTLGen consortium, the authors reported trans-eQTLs (P<5e-8) for 3,628 genes. After taking the linkage disequilibrium among SNPs into account and conducting the clumping analysis, a total of 9,882 independent trans-eQTLs were identified (Table S1). On average, a trans-eQTL explained 0.4% of variation in the expression of a gene which was lower than the value I computed for a cis- eQTL (1%). By annotating the trans-eQTLs, I noted the majority are located in genic regions (73%, N=7,207). This suggests the likely mechanism through which a trans-eQTL acts is by changing the expression of a gene which in turn impacts the expression of the target gene.

A number of trans-eQTLs had large impacts on expression of genes (Table S1). For example, rs1427407-T within BCL11A gene on chromosome 2, explained 12% of variation in expression of the gamma globin gene (HBG1); furthermore, rs9399137-C within the intergenic region of HBS1L-MYB on chromosome 6 explained 14% of variation in expression of HBG1. These findings are in line with previously published results indicating trans acting loci on chromosomes 6 and 2 impact the expression of HBG1. (Lettre et al., 2008)

ARHGEF3 locus is reported to impact platelet activation. Here, I found rs1354034-T within this gene contributes to this effect by impacting the expression levels of several genes involved in cellular adhesion including ITGB3, PPBP, PARVB, ITGA2B, SH3BGRL2, MMRN1, and CALD1. Additional examples of trans-eQTLs with large impact are available from Table S1.

While majority of genes were associated with a few number of trans-eQTLs, I noted a number of genes are associated with numerous loci, indicating they have a polygenic mode of inheritance. For example, HBM (hemoglobin subunit mu), CLEC1B (calcium-dependent lectin domain family 1 member B), MYL9 (myosin light chain 9), and ABCC3 (ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 3), were under the regulatory impact of more than 20 independent trans-eQTLs (P<5e-8) spread across the genome (Figure S1).

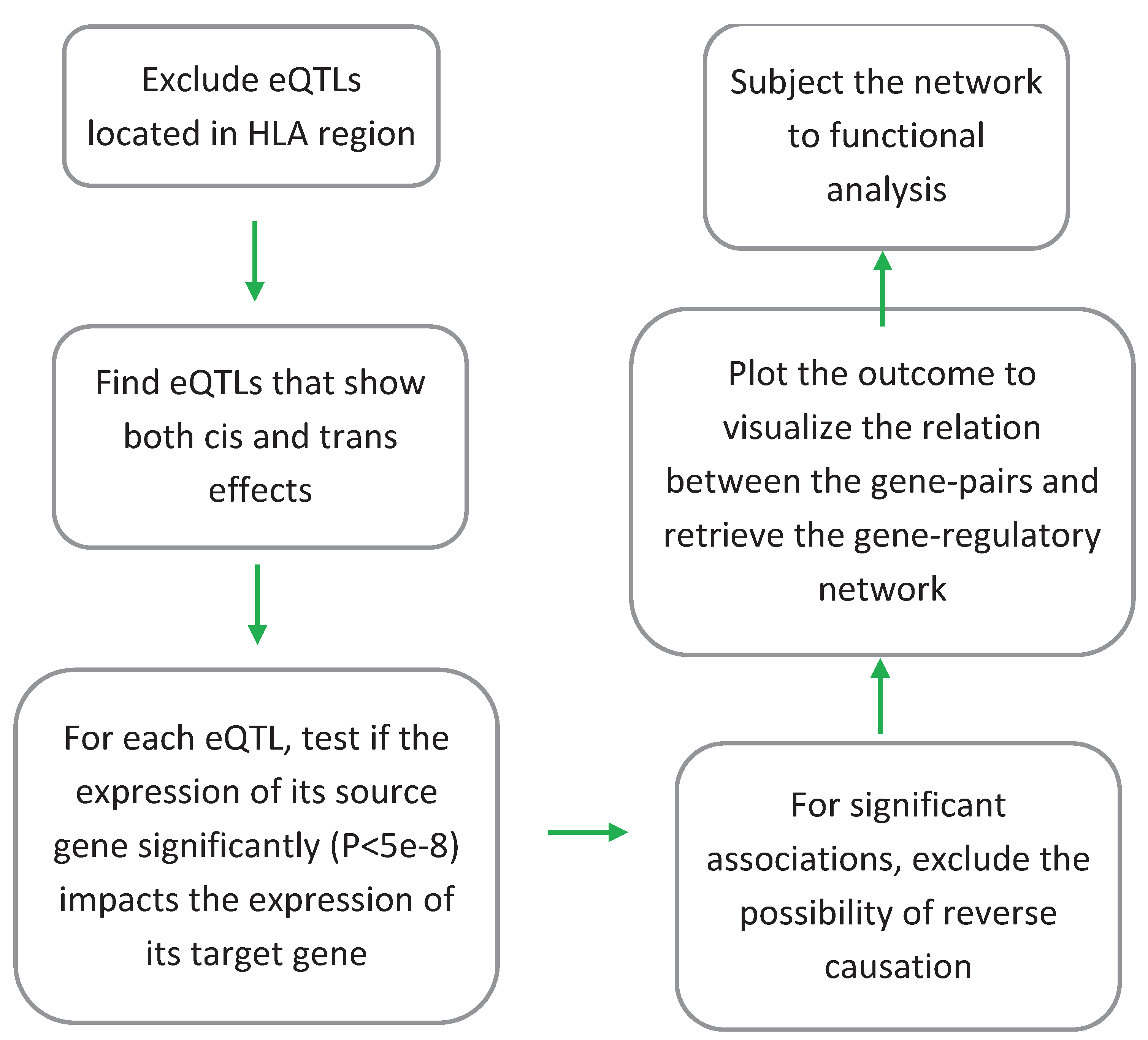

Identifying the Source Genes

I used the analytical pipeline described in Figure 1 to identify source gene(s) through which a trans-eQTL acts. Initially, I searched for eQTLs (P<5e-8) that display both trans and cis effects. Next, Mendelian randomization was used to examine if change in the expression of the source gene impacts the expression of the target gene. Reverse MR was also conducted by swapping the places of the source and the target gene in the equation to rule out the possibility of bi-directional association.

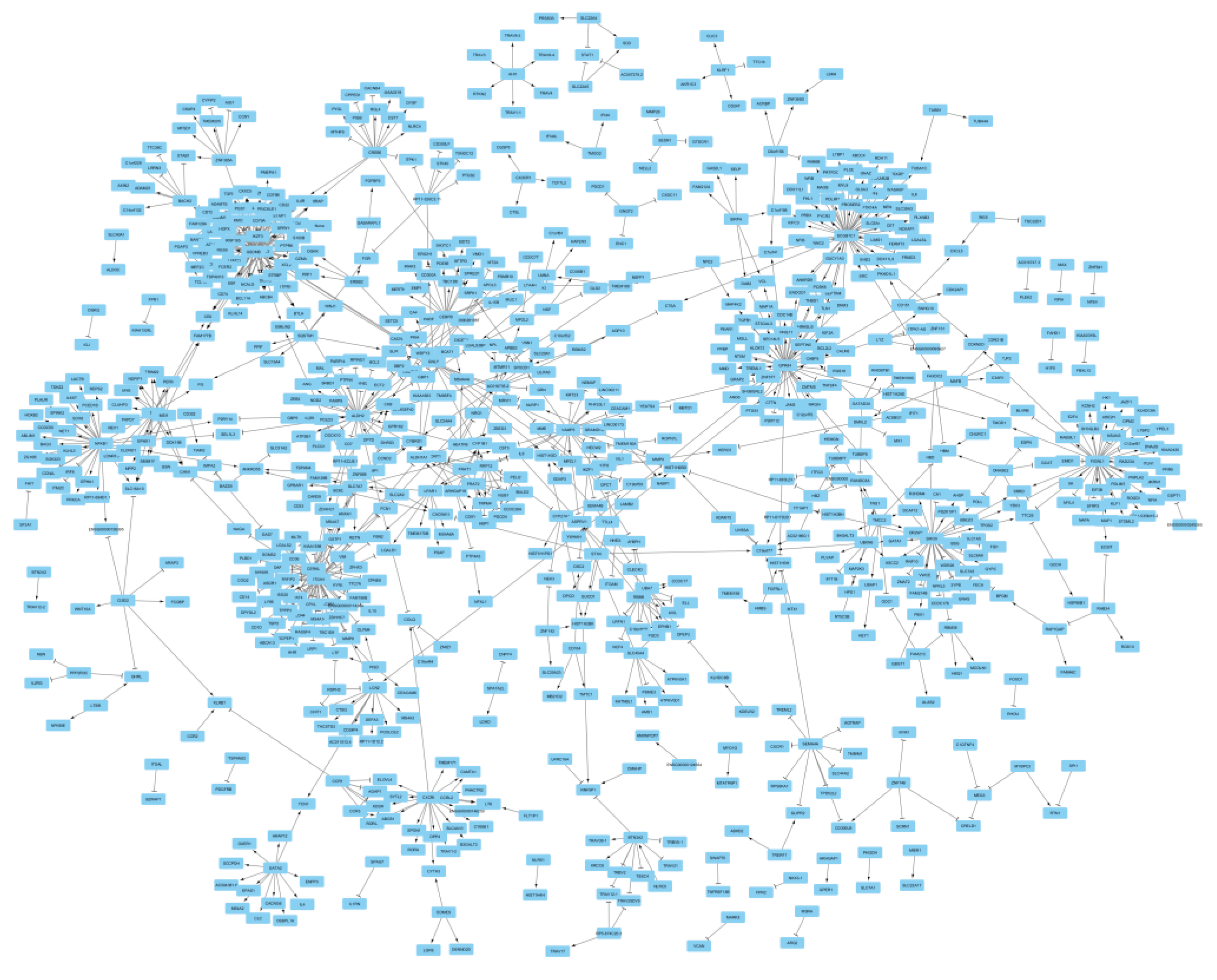

Following this procedure, I identified a total of 169 genes that exerted the trans-regulatory impact (P<5e-8) on 692 genes (Table S2). The source-target gene pairs obtained from this step, then were plotted to view the nature of relation between them. Figure 2 provides an overview of the interactions between the identified gene pairs. 90% of genes (N=749) aggregated into a network. The outcome of gene ontology enrichment analysis highlighted overrepresentation of hemo-immune processes among genes of the network (Table 1). To examine the validity of the results, a simulation step was also undertaken by generating 1000 random genesets that had similar size to the network (N=749 genes). I then searched for biological processes that are significantly associated with each geneset using gprofiler2 (Kolberg et al., 2023) that allows systematic search for enriched GO-biological processes through its R package (version 0.2.2). The outcome of the analyses was mainly null and revealed a few unrelated biological processes (Table S3).

As depicted in Figure 2, the main network displayed a scale-free topology. Distribution of the nodes by the frequency of their edges also indicated a power law distribution (Figure S2). 88% of the nodes had in average 1.5 edges while a group of 10 nodes (SCGB1C1, ORMDL3, GSDMB, ITGA4, GPR84, FIGNL1, ALDH2, SMOX, CERKL, and NFKB1) had more than 30 edges (accounted for 22% of interactions in the network). In a scale-free network, targeting the hub nodes are key in regulating the function of the network. As such, I investigated the association of the identified hub genes with the phenome. The analysis revealed ORMDL3, and GSDMB on chromosome band 17q21 are associated with several diseases of immune origin. Both genes appeared to be co-expressed as their underpinning eQTLs display correlated effect sizes (Figure S3). Mendelian randomization then revealed higher expression of these genes contribute to higher risks of allergic disease, asthma, atrial fibrillation but lower risks of primary biliary cholangitis, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis and lower levels of HDL (Table 2). Furthermore, I noted an association between ALDH2 and obesity related traits. The outcome of Mendelian randomization revealed higher expression of ALDH2 contributes to higher risk of obesity (Table S4).

Figure 2.

Overview of gene-pairs identified in this study and the nature of associations among them. Mendelian randomization revealed a total of 169 genes that exerted trans-regulatory impacts on 692 genes. Majority of gene pairs aggregated into a network with the scale free topology. An edge with an arrow end indicates as the expression of the source gene increases, the expression of the target gene increases as well; whereas, an edge with a T end indicates an inverse association. Summary association statistics detailing the nature of association between gene pairs are provided in

Table S2.

Figure 2.

Overview of gene-pairs identified in this study and the nature of associations among them. Mendelian randomization revealed a total of 169 genes that exerted trans-regulatory impacts on 692 genes. Majority of gene pairs aggregated into a network with the scale free topology. An edge with an arrow end indicates as the expression of the source gene increases, the expression of the target gene increases as well; whereas, an edge with a T end indicates an inverse association. Summary association statistics detailing the nature of association between gene pairs are provided in

Table S2.

Table 1.

Biological processes that are overrepresented in genes of the main network.

Table 1.

Biological processes that are overrepresented in genes of the main network.

| GO Term |

Description |

Fold Enrichment |

P |

Corrected P* |

| 0071222 |

Cellular response to lipopolysaccharide |

4.5 |

3.1e-11 |

1.1e-7 |

| 0006955 |

Immune response |

2.5 |

1.3e-7 |

4.6e-4 |

| 0006954 |

Inflammatory response |

2.5 |

8.9e-7 |

0.003 |

| 0007155 |

Cell adhesion |

2.2 |

2.0e-6 |

0.007 |

| 0070527 |

Platelet aggregation |

6.5 |

5.7e-6 |

0.02 |

| 0098609 |

Cell-cell adhesion |

3.2 |

1.2e-5 |

0.04 |

| 0019722 |

Calcium-mediated signaling |

4.5 |

1.3e-5 |

0.05 |

Table 2.

Higher expression of GSDMB and ORMDL3 impact several diseases of polygenic nature.

Table 2.

Higher expression of GSDMB and ORMDL3 impact several diseases of polygenic nature.

| Trait information |

GSDMB expression |

ORMDL3 expression |

| Name |

PMID |

B |

SE |

P |

B |

SE |

P |

| Asthma |

32296059 |

0.11 |

0.01 |

3.1e-71 |

0.13 |

0.01 |

1.4e-67 |

| Allergic disease |

29083406 |

0.07 |

0.01 |

2.7e-29 |

0.07 |

0.01 |

1.6e-27 |

| Atrial fibrillation |

30061737 |

0.04 |

0.01 |

1.3e-10 |

0.05 |

0.01 |

8.9e-11 |

| Type 1 diabetes |

25751624 |

-0.13 |

0.02 |

6.2e-10 |

-0.15 |

0.02 |

5.6e-10 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

24390342 |

-0.09 |

0.02 |

1.1e-8 |

-0.11 |

0.02 |

1.2e-8 |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis |

26394269 |

-0.23 |

0.04 |

1.9e-10 |

-0.28 |

0.04 |

1.2e-11 |

| HDL cholesterol |

32203549 |

-0.02 |

0.002 |

1.0e-33 |

-0.03 |

0.002 |

1.5e-36 |

| Ulcerative colitis |

26192919 |

-0.13 |

0.01 |

5.7e-21 |

-0.15 |

0.02 |

1.0e-20 |

| Crohn's disease |

26192919 |

-0.12 |

0.01 |

8.2e-20 |

-0.14 |

0.02 |

1.1e-19 |

Discussion

Gene regulatory network (GRN) enables a cell to specialize in carrying out its function. There are various cell types in the body and identification of their GRNs are important for various biological purposes including to better diagnose and treat diseases. There are currently several approaches that can investigate such networks by analyzing the raw data available at individual levels. This hinders the possibility of collaboration among researchers in order to combine their data, to map gene-regulatory networks with higher statistical power. Furthermore, as indicated in the introduction, the existing methods make a number of assumptions for generating GRNs; however, such assumptions could introduce bias in presence of alternative scenarios. The method proposed in this study provides several benefits. First, it can scan the genome systematically (hypothesis-free) and identify genes whose transcripts are related. Second, it uses SNPs (eQTLs) to test the association between two gene transcripts as such, it is undisturbed by the impact of confounding environmental factors, because the distribution of alleles at conception is a random process (Mendel’s law of segregation). Third, it can determine if the association between a source and a target gene indicates causation, correlation or reverse-causation because it uses Mendelian randomization for association testing. As a result, the generated network is directed. Fourth, it uses eQTL summary association statistics that are publicly available as such, it provides a convenient path for researchers who wish to share their data or combine findings from several studies to identify GRNs with higher statistical power.

By applying the devised workflow to eQTL data for blood, I detected gene pairs that aggregated into a gene-regulatory network. Examining the function of the network revealed it is associated with hemo-immune processes which is expected considering the examined eQTL data are from blood. The topology of the network resembles the properties of a scale free network (Barabási and Albert, 1999). A core of 10 genes (1.3% of nodes) accounted for 22% of the interactions and the distribution of interactions per gene followed a power law distribution (Figure S2). If this happens to be the case in other cell types then this provides a convenient path for therapeutic interventions, because a scale free network is manageable by targeting its hub genes.

On average a trans-eQTL explained 0.4% of variation in expression of a gene which is in line with previous findings (Consortium, 2020, Nica and Dermitzakis, 2013). Therefore, studies that aim to identify GRNs using trans-eQTLs, should obtain their eQTL data from studies with large sample sizes. For a well-powered analysis (statistical power>80%), the eQTL data (with P<5e-8) should come from a study with a sample size ≥ 11,000 individuals.

eQTL studies tend to report significant findings only, however, to fairly examine the association between two genes, access to full GWAS summary statistics data is required. This is important considering there are genes under the influence of numerous loci (Figure S1). Although, in the past publishing the full GWAS summary statistics was not feasible due to computational limits. Such a practice should not be a concern at present.

By examining the association of the network’s hub genes with the phenome. I found GSDMB and ORMDL3 impact several diseases of immune origin. Higher expression of these genes contributed to higher risks of allergic disease, asthma, atrial fibrillation but lower risks of primary biliary cholangitis, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis and lower levels of HDL. This finding indicates therapeutic approaches that aim to change the expression of these genes, should find an optimal threshold that balances the antagonistic peliotropic effect of these genes. Otherwise, side effects are expected.

ORMDL3 is localized to the endoplasmic reticulum and regulates downstream pathways including sphingolipids, metalloproteases, remodeling genes, and chemokines. GSDMB encodes gasdermin B, a member of gasdermin domain containing proteins which are involved in different processes associated with cellular state, such as cell cycle control, differentiation, and apoptosis (Das et al., 2017). The analyses revealed higher expression of these genes have concordant effects on several disorders of immune origin. Therefore, they may act through the same molecular pathway to impact diseases of immune origin. In this regard, inflammation is notable because ORMDL3 is involved in the development of the unfolded protein response, which triggers an inflammatory response including the formation of gasdermin pores on cellular wall and pyroptosis.

I also found an association between ALDH2 and the risk of obesity. Higher expression of ALDH2 contributed to higher risk of obesity. Several mechanisms have been suggested in this regard including the impact of ALDH2 on alcohol use behavior and subsequent changes on energy intake, appetite control, systemic inflammation, hormone levels, etc., as well as, the impact of ALDH2 on oxidizing the endogenous acetaldehyde during the oxidative stress (Hu, 2019).

In summary, this study describes a workflow to identify tissue-specific gene-regulatory networks. The proposed workflow complements previous approaches as it uses genetic information (i.e. eQTL summary statistics) to infer causal interactions and generates a directed gene regulatory network through a hypothesis-free genome-wide scan; furthermore, because the introduced workflow relies on eQTL data, it provides a convenient path for researchers who wish to combine data from several studies to identify GRNs with higher statistical power. The network identified in this study showed the scale-free topology. If further researches prove this is the inherent property of tissue/cell specific networks, then in each network, targeting the hub genes could prevent disease outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

This research work was enabled in part by computational resources and support provided by the Compute Ontario and the Digital Research Alliance of Canada.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

References

- BADIA-I-MOMPEL, P.; WESSELS, L.; MÜLLER-DOTT, S.; TRIMBOUR, R.; RAMIREZ FLORES, R. O.; ARGELAGUET, R.; SAEZ-RODRIGUEZ, J. Gene regulatory network inference in the era of single-cell multi-omics. Nature Reviews Genetics 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BARABÁSI, A.-L.; ALBERT, R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science 1999, 286, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CHANG, C. C.; CHOW, C. C.; TELLIER, L. C.; VATTIKUTI, S.; PURCELL, S. M.; LEE, J. J. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. GigaScience 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CONSORTIUM, G. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 2020, 369, 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DAS, S.; MILLER, M.; BROIDE, D. H. Chapter One - Chromosome 17q21 Genes ORMDL3 and GSDMB in Asthma and Immune Diseases. In Advances in Immunology; ALT, F. W., Ed.; Academic Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- DAVEY SMITH, G.; HEMANI, G. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Human Molecular Genetics 2014, 23, R89–R98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HU, C. Aldehyde dehydrogenases genetic polymorphism and obesity: from genomics to behavior and health. Aldehyde Dehydrogenases: From Alcohol Metabolism to Human Health and Precision Medicine 2019, 135–154. [Google Scholar]

- HUANG, D. W.; SHERMAN, B. T.; LEMPICKI, R. A. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Research,.

- HUANG, D. W.; SHERMAN, B. T.; LEMPICKI, R. A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nature protocols 4, 44–57. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KOLBERG, L.; RAUDVERE, U.; KUZMIN, I.; ADLER, P.; VILO, J.; PETERSON, H. g:Profiler—interoperable web service for functional enrichment analysis and gene identifier mapping (2023 update). Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, W207–W212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LETTRE, G.; SANKARAN, V. G.; BEZERRA, M. A. C.; ARAÚJO, A. S.; UDA, M.; SANNA, S.; CAO, A.; SCHLESSINGER, D.; COSTA, F. F.; HIRSCHHORN, J. N.; ORKIN, S. H. DNA polymorphisms at the BCL11A, HBS1L-MYB, and beta-globin loci associate with fetal hemoglobin levels and pain crises in sickle cell disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 11869–11874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MCCALLA, S. G.; FOTUHI SIAHPIRANI, A.; LI, J.; PYNE, S.; STONE, M.; PERIYASAMY, V.; SHIN, J.; ROY, S. Identifying strengths and weaknesses of methods for computational network inference from single-cell RNA-seq data. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MERCATELLI, D.; SCALAMBRA, L.; TRIBOLI, L.; RAY, F.; GIORGI, F. M. Gene regulatory network inference resources: A practical overview. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 2020, 1863, 194430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICA, A. C.; DERMITZAKIS, E. T. Expression quantitative trait loci: present and future. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2013, 368, 20120362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PARK, J.-H.; WACHOLDER, S.; GAIL, M. H.; PETERS, U.; JACOBS, K. B.; CHANOCK, S. J.; CHATTERJEE, N. Estimation of effect size distribution from genome-wide association studies and implications for future discoveries. Nat Genet 2010, 42, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PASANIUC, B.; PRICE, A. L. Dissecting the genetics of complex traits using summary association statistics. Nature Reviews Genetics 2017, 18, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PRICE, A. L.; HELGASON, A.; THORLEIFSSON, G.; MCCARROLL, S. A.; KONG, A.; STEFANSSON, K. Single-tissue and cross-tissue heritability of gene expression via identity-by-descent in related or unrelated individuals. PLoS Genet 2011, 7, e1001317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SHANNON, P.; MARKIEL, A.; OZIER, O.; BALIGA, N. S.; WANG, J. T.; RAMAGE, D.; AMIN, N.; SCHWIKOWSKI, B.; IDEKER, T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome research 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VÕSA, U.; CLARINGBOULD, A.; WESTRA, H.-J.; BONDER, M. J.; DEELEN, P.; ZENG, B.; KIRSTEN, H.; SAHA, A.; KREUZHUBER, R.; YAZAR, S.; et al. Large-scale cis- and trans-eQTL analyses identify thousands of genetic loci and polygenic scores that regulate blood gene expression. Nature genetics 2021, 53, 1300–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WANG, K.; LI, M.; HAKONARSON, H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Research 2010, 38, e164–e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ZHU, Z.; ZHANG, F.; HU, H.; BAKSHI, A.; ROBINSON, M. R.; POWELL, J. E.; MONTGOMERY, G. W.; GODDARD, M. E.; WRAY, N. R.; VISSCHER, P. M.; YANG, J. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nature genetics 2016, 48, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ZHU, Z.; ZHENG, Z.; ZHANG, F.; WU, Y.; TRZASKOWSKI, M.; MAIER, R.; ROBINSON, M. R.; MCGRATH, J. J.; VISSCHER, P. M.; WRAY, N. R.; YANG, J. Causal associations between risk factors and common diseases inferred from GWAS summary data. Nature communications 2018, 9, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).