3.1. Reflection of Light by a Moving Mirror

Unlike References [

1] and [

2], the same article,

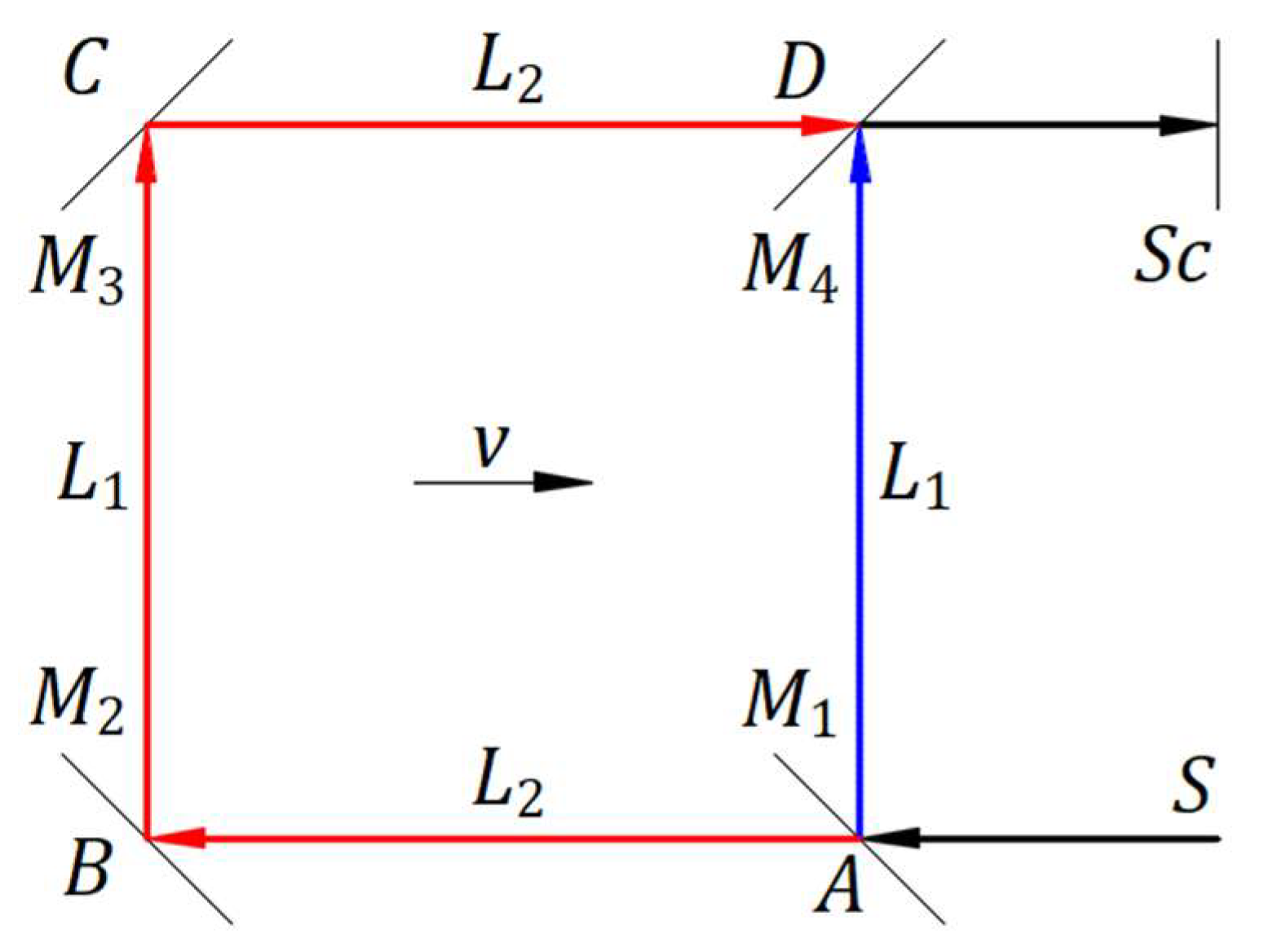

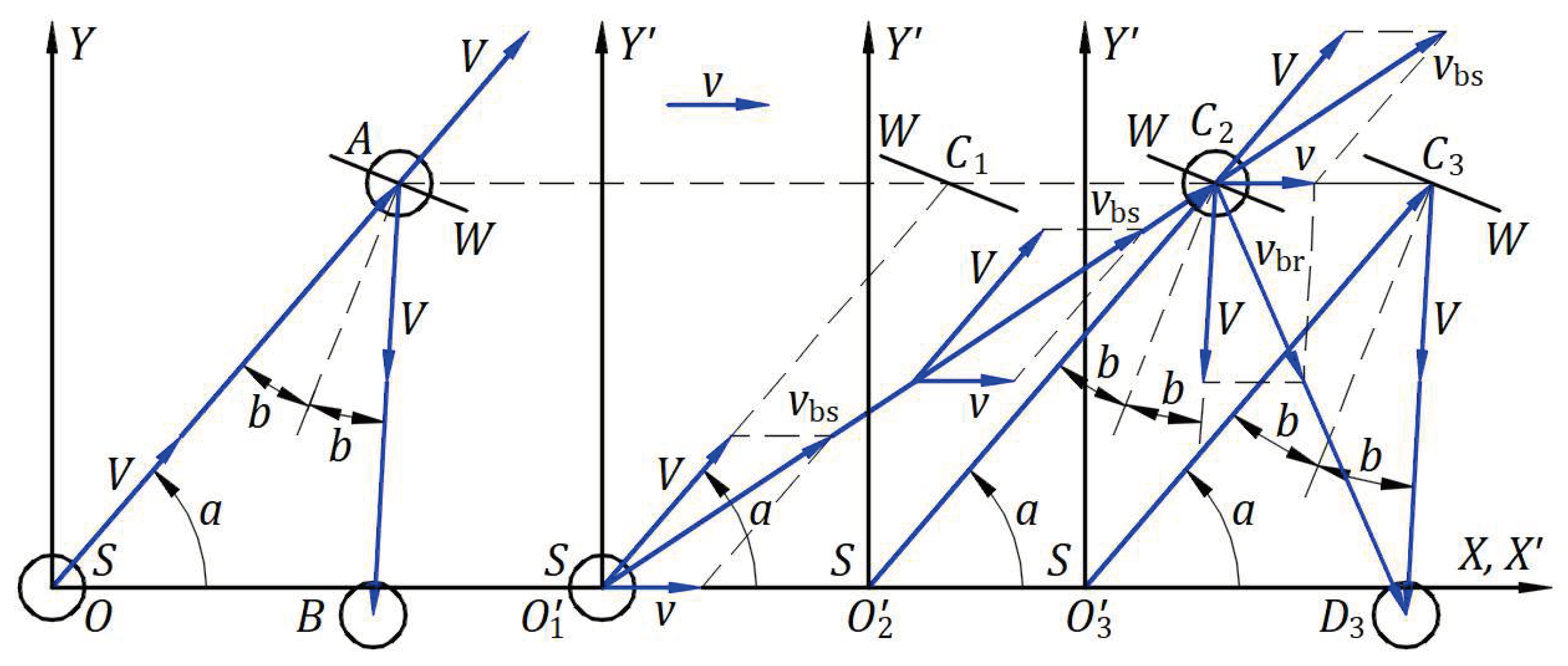

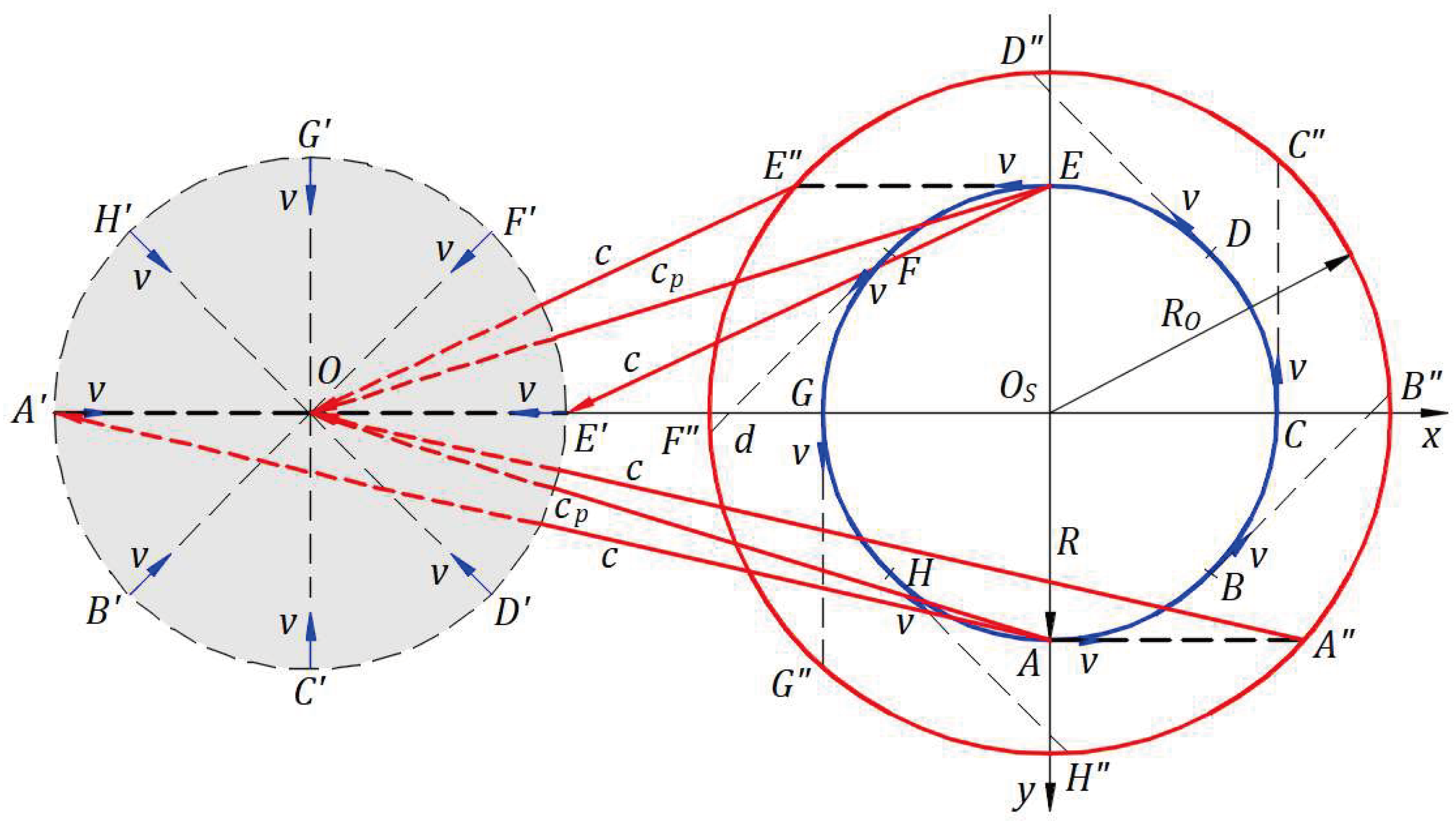

Figure 4 illustrates the absolute frame in which a mirror M travels at velocity

and a source S of coherent light is at rest.

This section employs Eq. (3)

, in which the reflected speed of light

in the absolute frame replaces

and speed

of electromagnetic nature replaces

.

In the absolute frame, the speed of the mirror in the opposite direction of incident light is , and the speed of the mirror in the direction of reflected light is .

A detailed form of Eq. (6) is

where angles

and

are measured counterclockwise from velocity

. In the absolute frame, the mirror moves in one direction, but the mirror inclination reflects light in multiple directions.

After a second from the initial instance at , the wavefront is at , and the mirror is at . The wavefronts reflected between and travel in the absolute frame in the direction at velocity . In the absolute and mirror’s inertial frames, the wavefronts travel from to , forming the light propagation as a continuous ray at velocity , wavelength , period , and frequency . A local observer at sees the light coming from emitted at speed , wavelength , period , and frequency . In the absolute frame, the mirror moves in one direction, but its inclination reflects light in multiple directions.

In References [

1] and [

2], the source is at rest in the inertial frame of the mirror, and the velocity of light is considered independent from the velocity of its source. The light ray reflected at point

comes from one point of source. In

Figure 4, wavefronts reflected in point

of the mirror belong to rays sequentially coming from the source.

The source may not be at rest; therefore, the source speed of light propagation is

in the absolute frame. In this case, the mirror may also perceive the source’s velocity. References [

6] and [

7], which are the same article, approach this situation.

3.2. Kinematics of Light as a Mechanical Phenomenon in Inertial Frames

Unlike Newtonian laws, we employ the expressions “observer in the absolute frame” and “observer in an inertial frame,” meaning that the observer is hypothetical and knows/oversees the phenomena in that frame. These terms may be eliminated and state how the phenomena are to be consistent with mechanics. However, the expression “local observer” must remain. A local observer perceives the phenomena by light coming directly from a source, reflected by objects from the observer’s frame or others, and partially reflected rays of a light beam traveling in a transparent medium such as air. In a vacuum, a beam of light is invisible, except when it comes directly to the human eye. Furthermore, the human eye observes only the light emitted from a source and its reflection in a mirror. Therefore, the physics phenomena are perceived by a local observer differently from reality given by Newtonian laws. Nevertheless, we may know reality better by applying Newtonian laws and local observation of light.

The study of emission, propagation, and reflection of light is based on that of balls, as described in

Section 2.4. In light case, velocity

of mechanical nature is the same as is for balls with mass or massless balls. Emitted velocity

, as defined by Maxwell’s equations, replaces emitted velocity

, wavefronts propagation velocity from source

given by the vector sum of velocities

and

replaces propagation velocity

, and wavefronts propagation velocity

from a mirror given by the vector sum of reflected velocity

and velocity

replaces propagation velocity

.

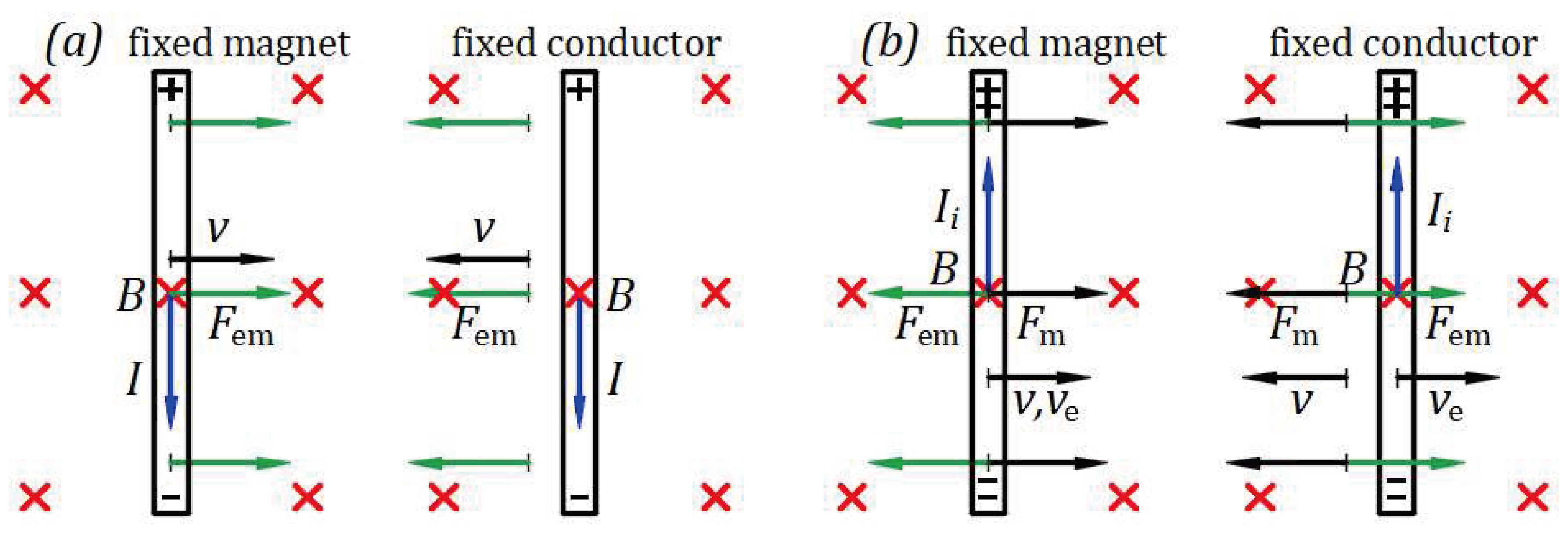

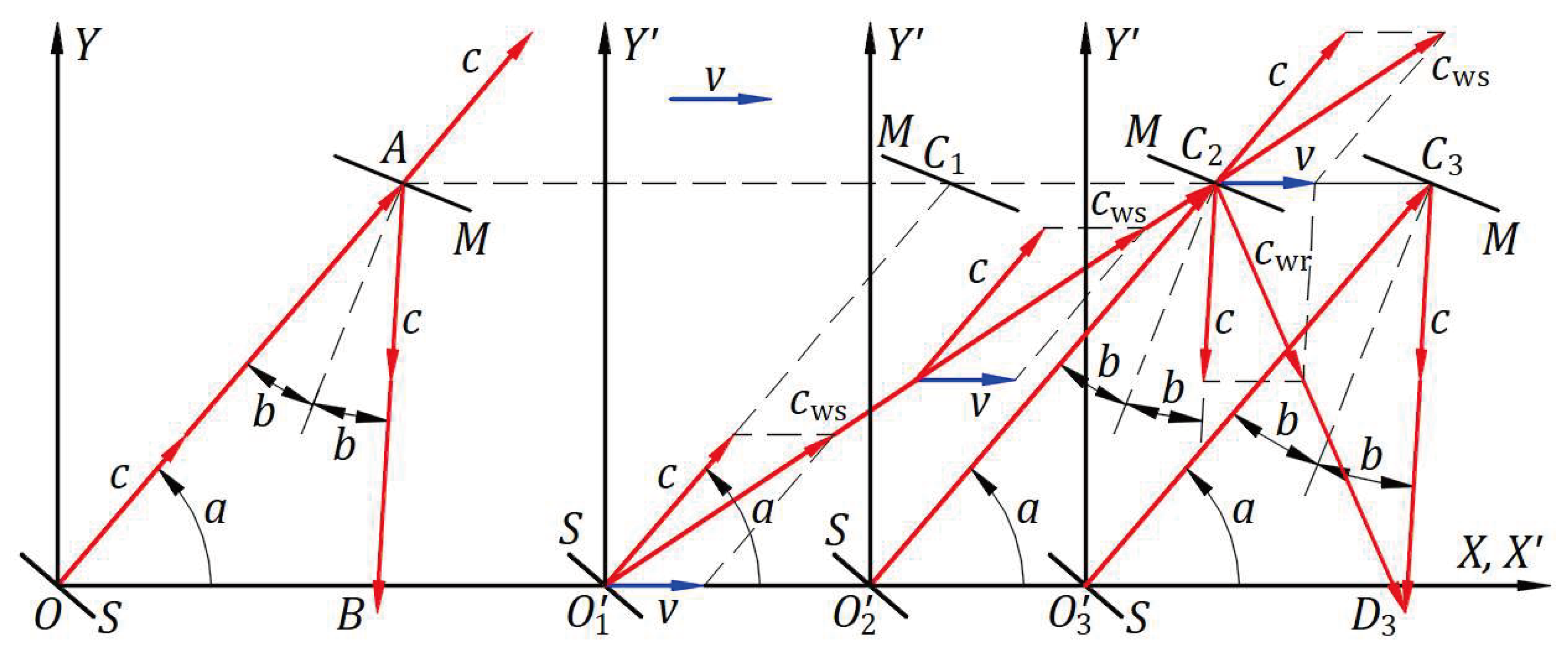

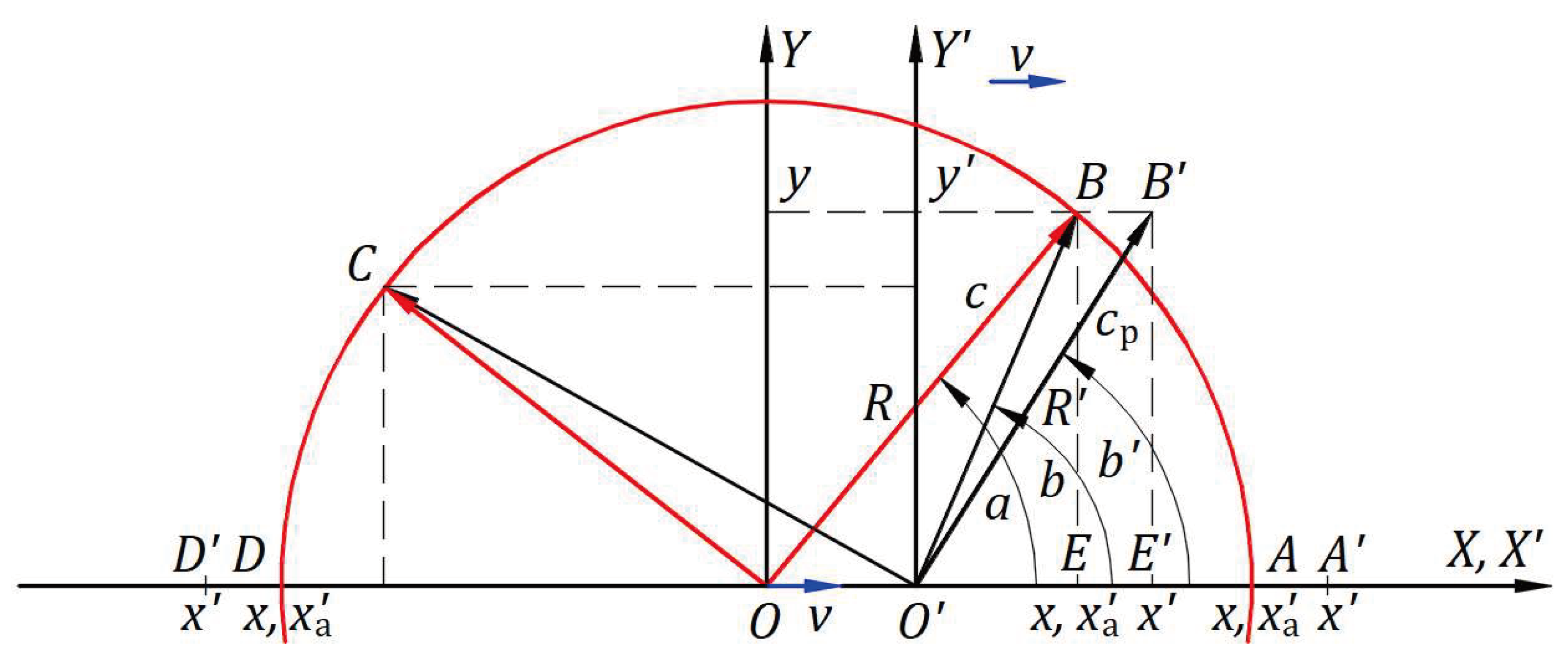

Figure 5 illustrates an inertial frame traveling in the absolute frame at velocity

. In the absolute frame

, a light source emits a wavefront at velocity

in direction

at an angle

from axis

. At point

, a mirror

reflects the wavefront with velocity

. After a time

from the instance of emission at

, the wavefront is at point

. The light on the paths

and

travels at speed

, wavelength

, period

, and frequency

.

In the inertial frame, , a source of light at origin and a mirror are at rest. Points and belong to the inertial frame, and their instances in the absolute frame have a corresponding index. At , the source emits a wavefront at velocity in direction at an angle from axis . Velocity drags the wavefront from the projected path at emission, , on propagation path, , at velocity . The dragging of the wavefront does not change the direction and magnitude of its emitted velocity but changes its propagation direction. Speed for this geometry. At point the wavefront is at , the direction makes an angle from axis , and light traveled the path at velocity , wavelength , period , and frequency . The light traveled in the inertial frame at as in the absolute frame.

In the inertial frame in which the source and mirror are at rest, the mirror perceives only the magnitude and direction of emitted velocity because, at collision, wavefronts and mirror have the same velocity . Hence, the wavefront’s velocity relative to the mirror is . The incident and reflected angle are measured from the normal to the mirror at the collision point to the incident and reflected velocity . After reflection, velocity keeps the same direction and magnitude. The wavefront moves at propagation velocity given by the vector sum of reflected velocity and velocity . Therefore, velocity drags the wavefronts from the projected direction of reflected velocity on the propagation path, , at velocity . After reflection, the propagation speed for this geometry.

At point the wavefront emitted from is at , the direction makes an angle from axis , and light traveled the paths and at velocity , wavelength , period , and frequency as the path and , respectively, in the absolute frame. In the inertial frame at point , the wavefront emitted from traveled from to and then to in time as in the absolute frame.

We can conclude that:

A source at rest in the absolute frame emits waves of light in all directions uniformly distributed in space at speed defined by Maxwell’s equations with wavelength and period . A source in motion emits wavefronts of light in the absolute frame in all directions independent of source velocity at speed . The source velocity drags each of the emitted wavefronts such that the waves in the source’s inertial frame are uniformly distributed in space and travel at speed with wavelength and period , as in the absolute frame.

In a source’s inertial frame, a mirror at rest perceives only the emitted direction of wavefronts, which are reflected accordingly. The source velocity continues to drag each of the reflected wavefronts, such that the waves travel at speed with wavelength and period in the inertial frame of the source.

In an inertial frame, the law of dragging applies to bodies at rest and in motion belonging to that inertial frame. The dragging is embedded in the laws of mechanics, including the kinematics of light. It works in the background of inertial frames. It acts on bodies and electromagnetic radiation created by bodies of each inertial frame, making phenomena as in the absolute frame. Therefore, the dragging explains and confirms the principle of relativity, according to which no experiment in an inertial frame can prove the motion of that frame. It explains that the laws of physics have the same form in each inertial frame, including electromagnetic radiation defined by Maxwell’s equations, and that the speed of light is the constant in the absolute and each inertial frame when the source and reflected mirror are at rest in those frames.

For theoretical studies, it is convenient to compare physics phenomena from inertial frames only to the frame at absolute rest, which is an inertial frame at zero speed. The kinematics of phenomena in each inertial frame are like in the frame at absolute rest. Therefore, each inertial frame can be considered a local frame at absolute rest for phenomena belonging to that inertial frame. To study interactions between physical systems belonging to two inertial frames, one can be considered a stationary/local frame at absolute rest in which another frame travels at the relative speed between the two frames.

3.3. Experiments and Observations that Support Kinematics of Light as a Mechanical Phenomenon

The kinematic of light as a mechanical phenomenon explains different experiments and local observations that supported special relativity due to insufficient and incorrect understanding.

1. Light travels through a transparent medium at a specific constant speed independent of source speed. Michelson and Morley [

13] considered their experiment in the fixed ether. Therefore, the emitted light speed and the incident and reflected light speed to a mirror have the same magnitude in the hypothetical ether of the absolute frame. In ether theory, the speed of light is limited by ether. The ether theory predicts a fringe shift, which is not confirmed by the zero fringe shift of the experimental results.

Differently, the kinematics of light demonstrate that in an inertial frame where a source of light and a mirror are at rest, the speed of light emitted by a source is limited at the constant of electromagnetic nature as in Maxwell’s equations. However, the light speed in the inertial frame of the source is the vector sum of velocity and velocity of the source of mechanical nature; emitted velocity remains unaffected by its dragging in magnitude and direction. Therefore, the kinematics of light predicts zero fringe shift for the Michelson‒Morley experiment in agreement with the experimental results.

2. Emission, propagation, and reflection of light in inertial frames [

4] explains the experiment performed at CERN, Geneva, in 1964 [

14] without rejecting Ritz’s ballistic theory [

15].

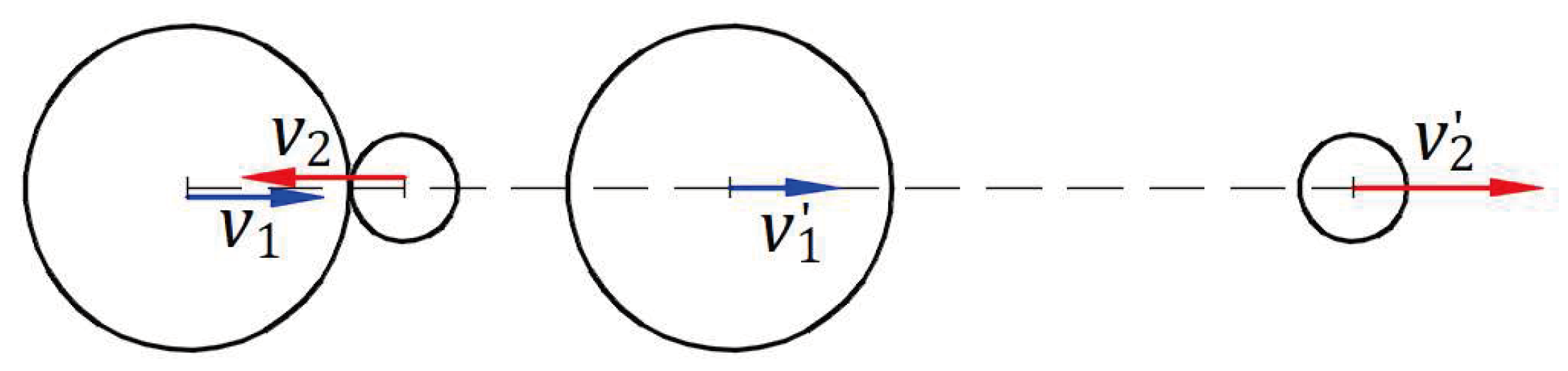

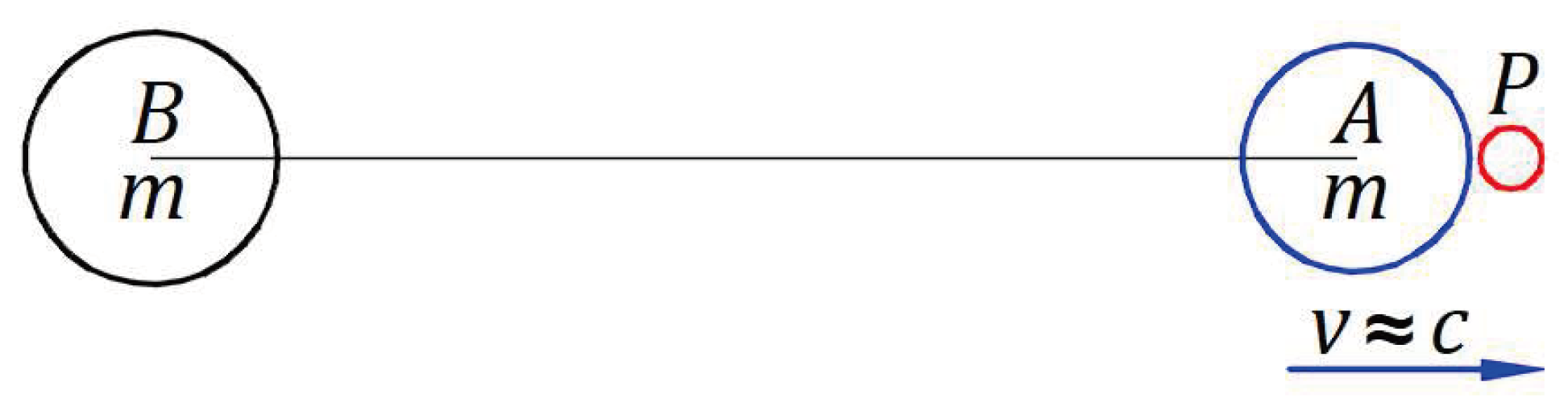

Figure 6 illustrates the phenomenon in a simplistic approach.

A boson of mass accelerated at a mechanical speed near the constant speed of light decays in a particle of mass and one massless photon. At speed , particle changes its direction, and the photon is moving free at speed . Bosons are only carriers that give photons only their mechanical speed near the constant speed of light . Bosons are not sources of light to give photons the speed of electromagnetic nature on top of speed of mechanical nature. This experiment confirms the dragging of light by source velocity.

3.

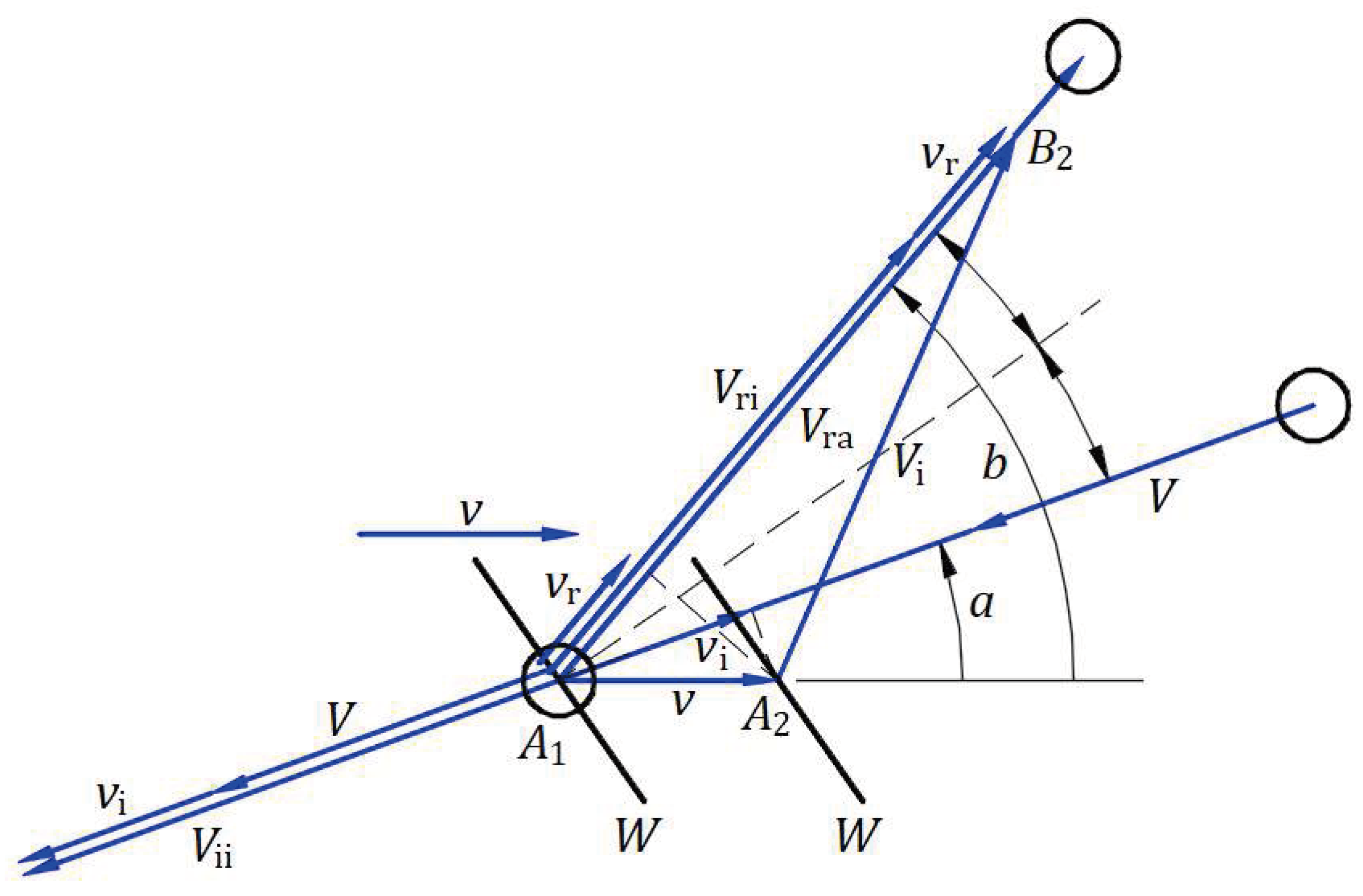

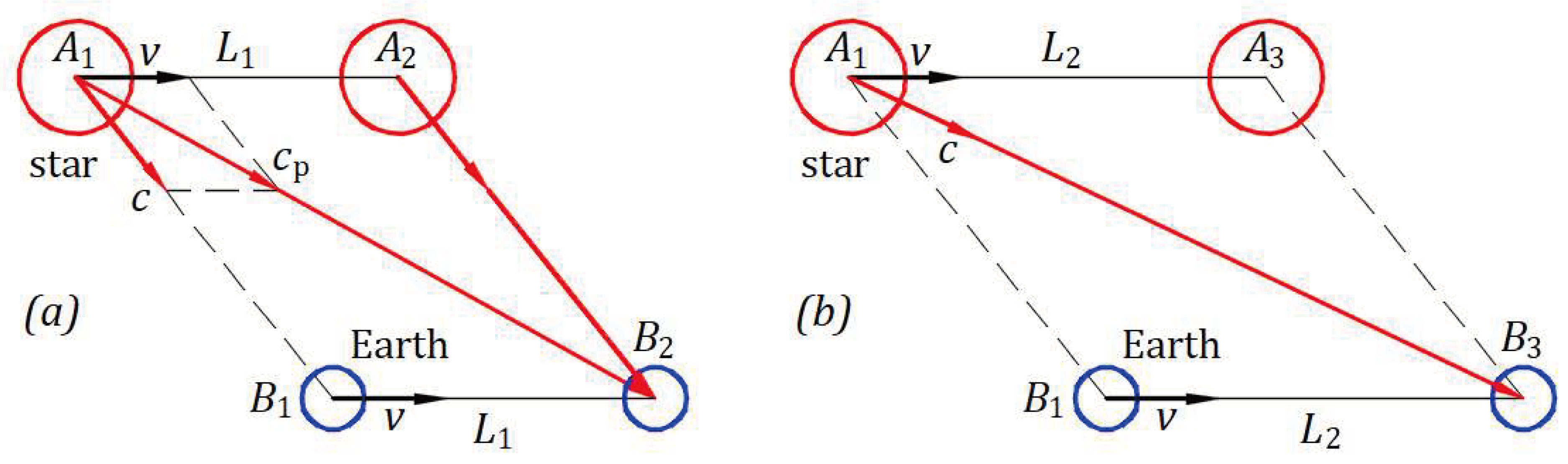

Figure 7(a) illustrates the observation of a star in the Universe according to the kinematics of light as a mechanical phenomenon. A star at point

and Earth at point

travel at velocity

. At this initial instance, the star emits a wavefront of light in the direction

at emitted speed

. After a time, the star travels at point

and Earth at point

the same length

, and velocity

drags the wavefront emitted in the direction

along

; at

, a local observer perceives the wavefront coming from

. Therefore, the star is seen at its actual location.

Figure 7(b) illustrates the observation of a star in the Universe according to the hypothesis that the speed of light is independent of the motion of the source, as in ether theory. A star at point

and Earth at point

travel at velocity

. At this initial instance, the star emits a wavefront of light in the direction

at emitted speed

. After a time, the star travels at point

and Earth at point

the same length

, and the wavefront emitted in the direction

reaches point

where a local observer perceives the wavefront coming from

. Therefore, the star is observed at the initial location, not its actual one, which means that the hypothesis of the light speed constancy creates irregularities unobserved by astronomers. These irregularities differ from those de Sitter incorrectly predicted. [

16,

17]

4. The emission of light as a mechanical phenomenon [

4] applies to observing a star’s orbit [

5].

Figure 8 depicts the actual star orbit of radius

in the plane of the paper and the imaginary circle of radius

with its plane parallel to the front of the paper plane. The distance

is perpendicular to the orbit and imaginary circle planes. The observer is at point

. The observed star orbit of radius

is centered at

. The view is from the back-right of the observer to have a clear image of the actual and observed orbit.

The distances in each set of ( and (), including all other similar distances corresponding to points , and are equal.

The emitted rays from the star in motion are dragged by the star velocity at the emission point through different paths to a local observer. At point , the star emits a wavefront of light at velocity in the direction that is dragged by velocity along the path at the propagation velocity . At point , the observer sees the wavefront coming from point at speed . At point , the star emits a wavefront of light at velocity in the direction that is dragged by velocity along the path at the propagation velocity . At point , the observer sees the wavefront coming from point at speed . The same observation occurs for each point of the circular orbit.

Points

, and

give the corresponding points

, and

that form the observed orbit with the center in

for this particular case. The local observer sees the star’s orbit rotated with a bigger diameter than the actual orbit. The speed of light from any point from the observed orbit to the observer is the constant

. Therefore, no time irregularities exist to reject Ritz’s ballistic theory, [

15] as de Sitter predicted, [

16,

17] and observing the star’s orbit supports the kinematics of light as a mechanical phenomenon. This study is an example of the phenomenon of an actual star orbiting and how a local observer views the observed orbit.

5. Emission, propagation, and reflection of light as mechanical phenomena applied to the Michelson interferometer with sunlight as a source [

8,

9] in Miller’s experiment [

18] at Cleveland Laboratory in 1924 are explained; the fringe shift is in the order of

. [

8,

9]

Miller mainly employed light from local sources in his experiments. The kinematic of light [

4] predicts zero fringe shift for any altitude location on Earth’s inertial frame. The experiments with local sources at Cleveland Laboratory in 1924 are explained by Reference [

4]. At Mount Wilson at high altitude, where experiments were performed with local sources, the fringe shift of 0.08 in 1921 and 0.088 in 1925 remain unexplained.

In Reference [

8], the author incorrectly considered that the experiments at Mount Wilson employed sunlight, which explains the fringe shifts of 0.08 and 0.088. The mistake was caught later in the review process. [

9] If there is no theoretical explanation, the attention may return to the ambiance of experiments and, in particular, to the device’s temperature uniformity.

6. Majorana’s experiment [

19] in Earth’s inertial frame employs a fixed light source. The light travels through three stages, each consisting of one movable and one fixed mirror, and enters a Michelson interferometer with unequal-length arms. The movable mirrors are fixed on a rotational disk in both directions. When the disk is at rest, a fringe image is observable. When the disk is rotated from the maximum speed of one direction to another, a shift of 0.71 fringes is observed [

19]. Like the Michelson interferometer, Majorana’s experimental device remains an outstanding contribution to the physics of light despite changes in experiment interpretation with time. Majorana misunderstood the phenomenon within the device and the significance of the fringe shift observed at the experimental time, explaining the fringe shift favorably to special relativity. The reflection of light as a mechanical phenomenon [

1,

2,

4] applied to the Majorana experiment [

10] shows that the speed of light changes after each stage, causing the fringe shift in the Michelson interferometer. Reference [

10] approximates rotational mirrors as inertial frames and derives a shift of 0.27 fringes. However, the observed shift of 0.71 fringes confirms the kinematics of light as a mechanical phenomenon and rejects the constancy of light.

7. Besides interactions of emission and reflection of light with matter, another example is the refraction of light when it travels from one medium to another at rest, according to Snell’s law. Airy’s experiment is an example of the dragging of light by a moving medium. Airy [

20] expected to adjust the telescope’s inclination after introducing a tube with water along its axis, but that was unnecessary. Considering the dragging of light by the moving water and the experiment result, we obtained the Fresnel dragging coefficient

from a mechanics perspective, [

11] where

is the medium’s refraction index.

3.4. Galilean Transformation

We study Galilean transformation as in mechanics, where physics phenomena are as they are and without observations.

All inertial frames extended to infinite overlap. The phenomenon in an inertial frame is shared instantly in any other inertial frame. The inertial frame in which a phenomenon is to be shared is considered at relative rest/stationary frame.

Galilean transformation offers how a physics phenomenon, including emission, propagation, and reflection of light as mechanical phenomena, is shared instantly from a stationary frame in an inertial frame.

Figure 9 depicts a stationary frame

in which an inertial frame

travels at relative velocity

along the

axis, and the planes

and

coincide.

The kinematics of light prove that in a stationary frame, light rays from a source at rest are uniformly distributed and travel at speed ; we do not assume these phenomena.

Origins

and

coincide at the initial instance when the source belonging to origin

of the stationary frame emits a spherical wavefront of light formed by individual ray wavefronts. After a time

, the spherical wavefront of light has its center at

, and the origin of the inertial frame is at

at a distance

from

. Galilean transformation offers the coordinates of each ray wavefront on the spherical wavefront.

Figure 9 shows at a time

the ray wavefronts at points

,

,

, and

on the circular wavefront in plane

and their coordinates in plane

.

The ray wavefront emitted in direction at the initial instance travels in this direction at all times, and it is at all times on this spherical wavefront, which enlarges continuously. This ray wavefront travels length in the inertial frame at the propagation velocity . The vector difference of vector and vector gives velocity illustrated at points and . This ray wavefront travels at the same angle and velocity for any other instance of the spherical wavefront. This process is identical for each ray wavefront on the spherical wavefront. However, velocity of ray wavefronts varies with angle . Therefore, the directions of the ray wavefronts are not uniformly distributed in the space of the inertial frame. The ray density increases from to .

Galilean transformation, in its simplest form, consists of four equations applicable to each ray wavefront of a spherical wavefront:

Figure 9 and the Galilean transformation apply identically to a hypothetical ball source when the source emits a spherical ball front and the speed of balls

.

Figure 9 may be deceiving. It may suggest that the spherical wavefront also belongs to the inertial frame, which is incorrect. The set of Eqs (8) gives just the location of coordinates of the spherical wavefront in the inertial frame at a time

. The phenomenon of light propagation of the physical system consisting of a source and spherical wavefront belongs to the stationary frame. The source, which has its coordinate

, and the spherical wavefront do not belong to the inertial frame. A phenomenon in an inertial frame is unique in the Universe and instantly shared in each inertial frame, not duplicated. The laws of physics have the same form in each inertial frame, and the phenomenon of a stationary frame is independent of any other inertial frame. There are no transformations of phenomena from stationary frame to inertial frame to undergo changes that may or may not affect the physics laws of those phenomena. The term transformation may be inappropriately used. It may suggest that a phenomenon obeys rules, laws, or hypotheses to be transformed from one inertial frame to another when it is a simple sharing. A better wording may be Galilean coordinates.