Submitted:

16 April 2024

Posted:

16 April 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Inflorescence Architecture

1.2. The Change from Fruit-Forming to Non-Fruit-Forming Flowers

1.3. Genotypes

1.4. Development of the Mat (Genet)

1.5. Inflorescence Architecture and Environment

2. Results

2.1. Measured Data: Hb, Fh, Fb, Pr and Pf

2.2. Changes to the Data Caused by Modification

2.3. Coefficients of the Exponential Reciprocal Function, r, C, Tb and A

2.4. Modified Data: Hb, Fh, Fb, Pr and Pf

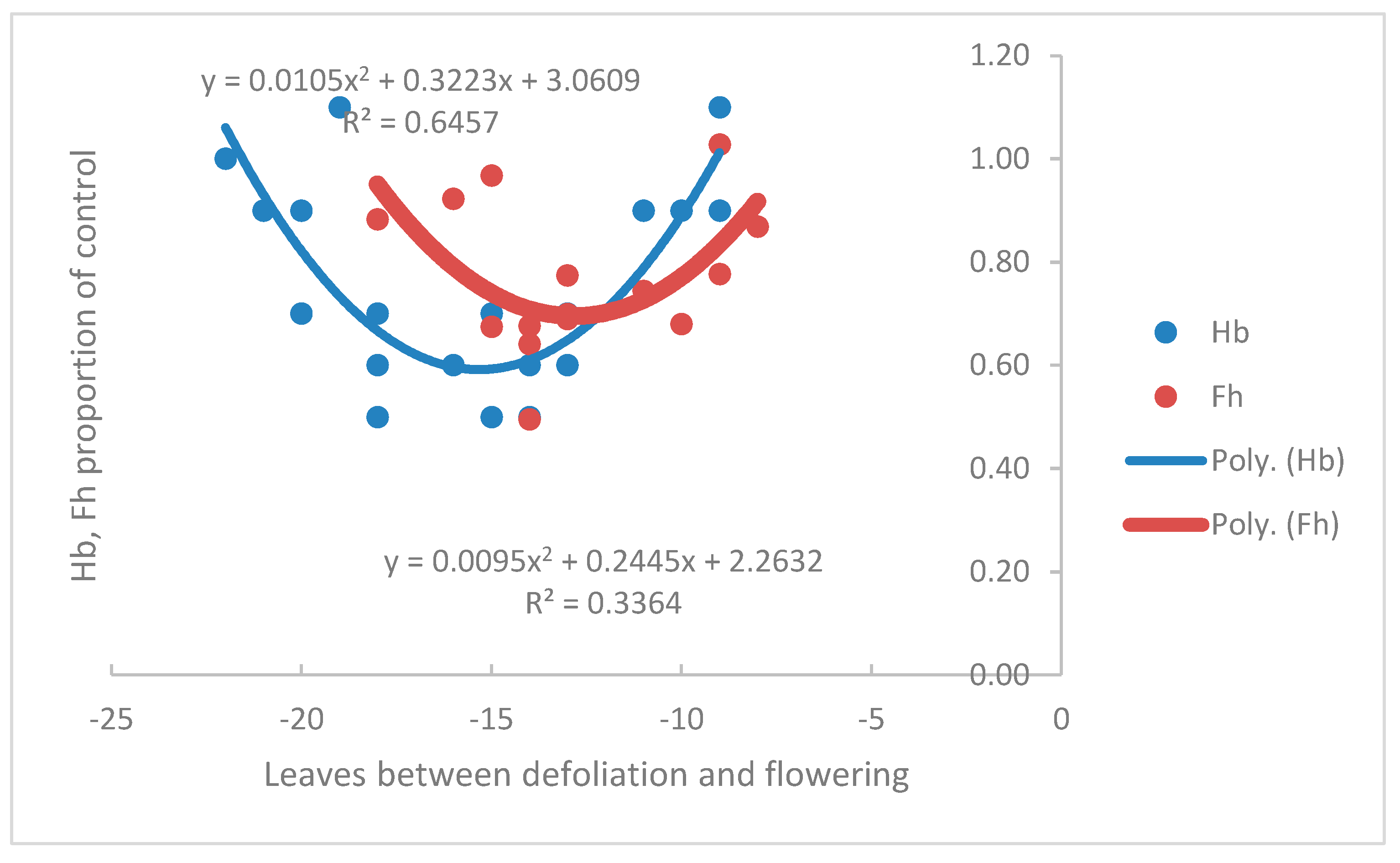

2.5. The Balance between Rate, R, and Time, Ti, in Determining Hb and Fh

3.6. Effect of the Genet on Hb, Fh and Fb

3. Discussion

3.1. Fruit Per Bunch, Fb

3.2. Fruit Per Hand, Fh

3.3. Hands Per Bunch, Hb

3.4. Hb, Site Temperature and Resources

3.5. Plant Reserves and Inflorescence Architecture

3.6. Peduncle Total Length, Pr, and the Proportion that Was Female, Pf

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data and Its Analysis

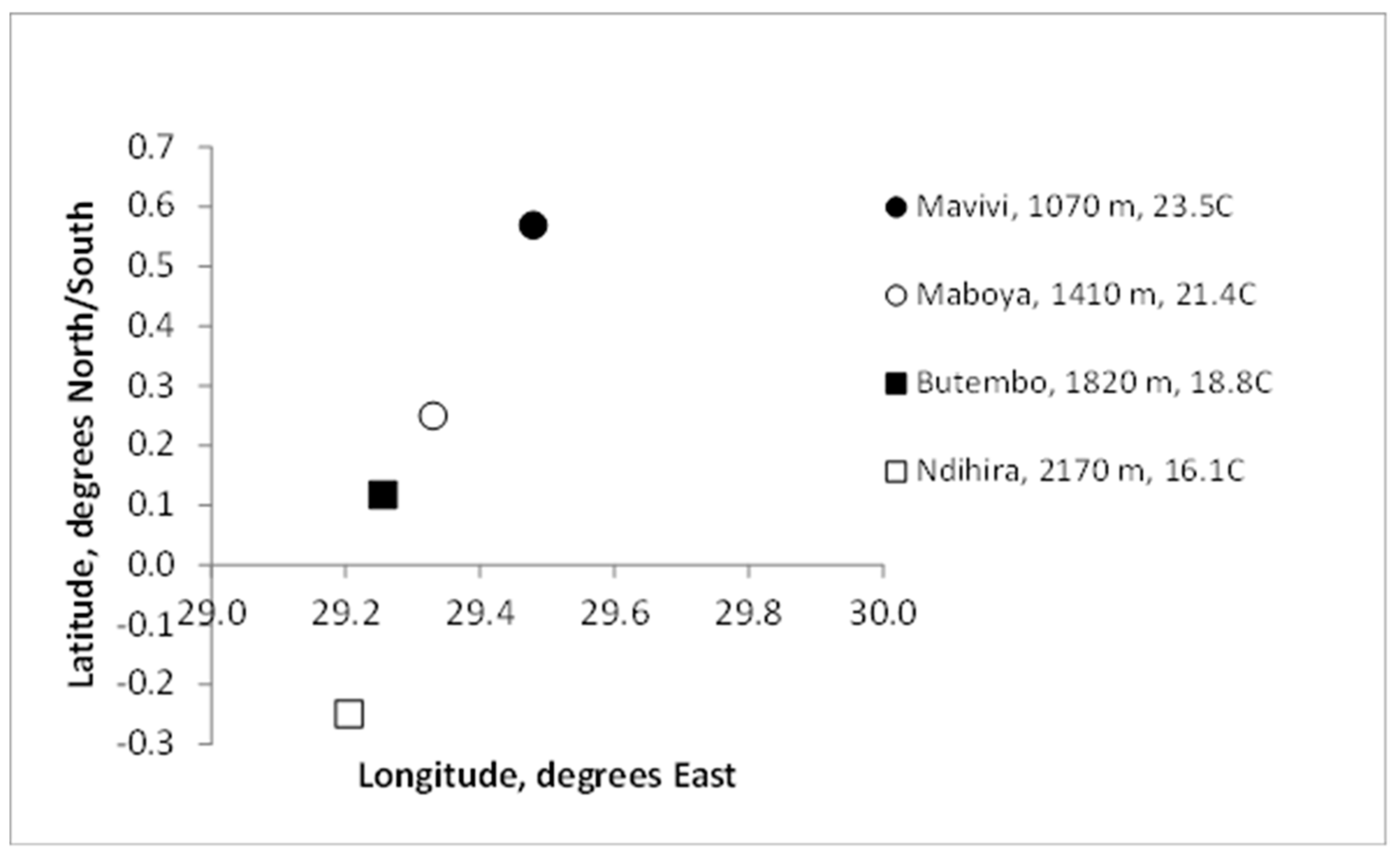

4.2. Sites, Cultivars and Clone-Sets

4.3. Development of the ‘Modified’ Data Set and the Calculated Data Set for Ndihira

4.4. Analyses of Measured and ‘Modified’ Data

4.5. The Exponential Reciprocal Function and the Curvature Coefficient

4.6. The Effect of the Genet

4.7. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adheka JG, De Langhe E. Characterisation and classification of the Musa AAB Plantain subgroup in the Congo Basin. Scripta Botanica Belgica 2018, 54, 1-104. [CrossRef]

- Adheka JG, Dhed’a DB, Karamura D, Blomme G, Swennen R, De Langhe E. The morphological diversity of plantain in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Scientia Horticulturae 2018, 234, 126-133. [CrossRef]

- Alexandrowicz L. ‘Etude du developpement de l’inflorescence du bananier Nain’. Annales 9, Institut des Fruits et Agrumes Coloniaux (IFAC), Paris, France. 1955.

- Allen RN. Epidemiological factors influencing the success of roguing for the control of Bunchy Top disease of bananas in New South Wales. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 1978, 29, 535-544. [CrossRef]

- Allen RN. Spread of Bunchy Top disease in established banana plantations. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 1978, 29, 1223-1233. [CrossRef]

- Allen RN, Dettmann EB, Johns GG, Turner DW. Estimation of leaf emergence rates of bananas. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 1988, 39, 53-62. [CrossRef]

- Amah D, Turner DW, Gibbs DJ, Waniale A, Gram G, Swennen R. ‘Overcoming the fertility crisis in bananas (Musa spp.)’. In ‘Achieving sustainable cultivation of bananas. Vol. 2. Germplasm and genetic improvement’. (Eds. G Kema, A Drenth). Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing Limited, Cambridge, UK. 2021, pp. 257-306.

- Argent GCG. The wild bananas of Papua New Guinea. Royal Botanical Gardens Edinburgh, Notes 1976, 35, 77-114.

- Argent GCG. Two interesting wild Musa species (Musaceae) from Sabah, Malaysia. Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore 2000, 52, 203-210.

- Baker JG. A synopsis of the genera and species of Musaceae. Annals of Botany 1893, 7, 189-222.

- Bartlett ME, Specht CD. Evidence for the involvement of GLOBOSA-like gene duplications and expression divergence in the evolution of floral morphology in the Zingiberales. New Phytologist 2010, 187, 521-541. [CrossRef]

- Blomme G, Ocimati W, Sivirihauma C, Vutseme L, Turner DW. The performance of a wide range of plantain cultivars at three contrasting altitude sites in North Kivu, Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Fruits 2020, 75, 21-35. [CrossRef]

- Daniells, JW, O’Farrell PJ. Effect of cutting height of the parent pseudostem on yield and time of production of the following sucker in banana. Scientia Horticulturae 1987, 31, 89-94. [CrossRef]

- De Langhe E. La taxonomie du bananier plantain en Afrique Equatoriale. Journal d’agriculture tropicale et de botanique appliquee 1961, 8 (10-11), 417-449.

- Dodsworth S. Petal, sepal, or tepal? B-genes and monocot flowers. Trends in Plant Science 2017, 22 (1), 8-10. [CrossRef]

- Eckstein K, Robinson JC. The influence of the mother plant on sucker growth, development, and photosynthesis in banana (Musa AAA: Dwarf Cavendish). Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 1999, 74, 347-350. [CrossRef]

- Fahn A. The origin of the banana inflorescence. Kew Bulletin 1953, (3), 299-306. [CrossRef]

- Fortescue JA, Turner DW, Romero R. Evidence that banana (Musa spp.), a tropical monocotyledon, has a facultative long-day response to photoperiod. Functional Plant Biology 2011, 38, 867-878. [CrossRef]

- Friend DJC. Tillering and leaf production in wheat as affected by temperature and light intensity. Canadian Journal of Botany 1965, 43, 1063-1076. [CrossRef]

- Ganry J. Determination ‘in situ’ du stade de transition entre la phase vegetative et la phase florale chez le bananier, utilisant le ‘coefficient de Vitesse de croissance des feuilles’. Essai d’interpretation de quelques processus de developpement durant la periode florale. Fruits 1977, 32, 373-386.

- Ganry J. Le developpement du bananier en relation avec les facteurs du milieu: Action de la temperature et du rayonnement d’origine solaire sur la vitesse de croissance des feuilles. Etude du rythme de developpement de la plante. Fruits 1980, 35, 727-743.

- Irish V. The ABC model of flower development. Current Biology 2017, 27, R853-R909.

- Johns GG. Effects of bunch trimming and double bunch covering on yield of bananas during winter in New South Wales. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 1996, 36, 229-235. [CrossRef]

- Jullien A, Munier-Jolain, N.G., Malezieux, E., Chillet, M., Ney B. Effect of pulp cell number and assimilate availability on dry matter accumulation rate in a banana fruit (Musa sp. AAA group ‘Grande Naine’ (Cavendish sub-group)). Annals of Botany 2001, 88, 321-330. [CrossRef]

- Kirchoff BK. Inflorescence and flower development in Musa velutina H. Wendl. & Drude (Musaceae), with a consideration of developmental variability, restricted phyllotactic direction, and hand initiation. International Journal of Plant Science 2017, 178, 259-272. [CrossRef]

- Lahav E, Turner DW. ‘Fertilising for high yield – Banana’ 2nd edn. IPI Bulletin 7, International Potash Institute, Berne, Switzerland, 1989.

- Mayfield E. ‘Illustrated Plant Glossary’ CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, Australia, 2021.

- McIntyre BD, Speijer P, Riha SJ, Kizito F. Effects of mulching on biomass, nutrients, and soil water in banana inoculated with nematodes. Agronomy Journal 2000, 92, 1081-1085. [CrossRef]

- Mead R, Curnow RN, Hasted AM. ‘Statistical Methods in Agriculture and Experimental Biology’. 2nd Edn. Chapman & Hall, London, UK, 1993.

- Mekwatanakarn W, Turner DW. A simple model to estimate the rate of leaf production in bananas in the subtropics. Scientia Horticulturae 1989, 40, 53-62. [CrossRef]

- Moncur MW. ‘Floral development of tropical and subtropical fruit and nut species. An atlas of scanning electron micrographs. Division of Water and Land Resources, Natural Resources Series No 8, CSIRO, Australia, 1988.

- Nur N. Studies on pollination in Musaceae. Annals of Botany 1976, 40, 167-177. [CrossRef]

- Nyine M, Uwimana B, Akech V, Brown A, Ortiz R, Dolezel J, Lorenzen J, Swennen R. Association genetics of bunch weight and its component traits in East African highland banana (Musa spp. AAA group). Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2019, 132, 3295-3308. [CrossRef]

- Nyine M, Uwimana B, Swennen R, Batte M, Brown A, Christelova P, Hribova E, Lorenzen J, Dolezel J. Trait variation and genetic diversity in a banana genomic selection training population. PLoS ONE 2017, 12(6), e0178734. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. ‘R: A language and environment for statistical computing’. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2019.

- Ram HYM, Ram M, Steward FC. Growth and development of the banana plant, 3a. The origin of the inflorescence and the development of flowers. 3b. The structure and development of the fruit. Annals of Botany 1962, 26, 657-673. [CrossRef]

- Robinson JC, Human NB. Forecasting of banana harvest (‘Williams’) in the subtropics using seasonal variations in bunch development rate and bunch mass. Scientia Horticulturae 1988, 34, 249-263. [CrossRef]

- Robinson JC, Nel DJ. Comparative morphology, phenology, and production potential of banana cultivars ‘Dwarf Cavendish’ and ‘Williams’ in the Eastern Transvaal Lowveld. Scientia Horticulturae 1985, 25, 149-161. [CrossRef]

- Robinson JC, Nel DJ. Competitive inhibition of yield potential in a ‘Williams’ banana plantation due to excessive sucker growth. Scientia Horticulturae 1990, 43, 225-236. [CrossRef]

- Sass C, Iles WJD, Barrett CF, Smith SY, Specht CD. Revisiting the Zingiberales: using multiplexed exon capture to resolve ancient and recent phylogenetic splits in a characteristic plant lineage. Peer Journal 2016, 4:e1584.

- Savvides A, Dieleman JA, van Ieperen W, Marcelis LFM. A unique approach to demonstrating that apical bud temperature specifically determines leaf initiation rate in the dicot Cucumis sativus. Planta 2016, 243, 1071-1079. [CrossRef]

- Sikyolo I, Sivirihauma C, Ndungo V, De Langhe E, Ocimati W, Blomme G. ‘Growth and yield of plantain cultivars at four sites of differing altitude in North Kivu, Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo’. In ‘Banana Systems in the Humid Highlands of Sub-Saharan Africa – Enhancing Resilience and Productivity’. Eds. G Blomme, P van Asten, B Vanlauwe. CAB International, Wallingford, UK. 2013, pp. 48-57.

- Simmonds NW. Varietal identification in the Cavendish group of bananas. Journal of Horticultural Science 1954, 29, 81-88. [CrossRef]

- Simmonds NW. ‘The evolution of the bananas. Longmans, London, UK. 1962.

- Simmonds NW. ‘Bananas’. 2nd edn. Longman, London, UK. 1966.

- Sivirihauma C, Blomme G, Ocimati W, Vutseme L, Sikyolo I, Valimuzigha K, De Langhe E, Turner DW. Altitude effect on plantain growth and yield during four production cycles in North Kivu, Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Acta Horticulturae 2016, 1114, 139-148. [CrossRef]

- Summerville WAT. Studies on nutrition as qualified by development in Musa cavendishii Lamb. The Queensland Journal of Agricultural Science 1944, 1, 1-127.

- Swennen R, Vuylsteke D. ‘Morphological taxonomy of plantain (Musa cultivars AAB) in West Africa’. In ‘Banana and Plantain Breeding Strategies’. Eds. GJ Persley, EA De Langhe pp. 165-171. ACIAR Proceedings No 21, ACIAR Canberra. 1987, pp 165-171.

- Swennen R, Vuylsteke D, Ortiz R. Phenotypic diversity, and patterns of variation in West and Central African plantains (Musa spp., AAB group, Musaceae). Economic Botany 1995, 49, 329-327. [CrossRef]

- Swennen R, Wilson GF, De Langhe E. Preliminary investigation of the effects of gibberellic acid (GA3) on sucker development in plantain (Musa cv AAB) under field conditions. Tropical Agriculture (Trinidad) 1984, 61, 253-256.

- Tezenas du Montcel H, De Langhe E, Swennen R. Essai de classification des bananiers plantains (AAB). Fruits 1983, 38, 461-474.

- Tixier P, Dorel M, Malezieux E. A model-based approach to maximise gross income by selection of banana planting date. Biosystems Engineering 2007, 96, 471-476. [CrossRef]

- Turner DW. Effects of climate on rate of banana leaf production. Tropical Agriculture (Trinidad) 1971, 48, 283-287.

- Turner DW. Crop physiology of bananas – quo vadis? Madras Agricultural Journal 1981, 68, 78-84.

- Turner DW, Fortescue JA, Ocimati W, Blomme G. Plantain cultivars (Musa spp. AAB) grown at different altitudes demonstrate cool temperature and photoperiod responses relevant to genetic improvement. Field Crops Research 2016, 194, 103-111. [CrossRef]

- Turner DW, Gibbs DJ. ‘A functional approach to bunch formation in banana’. In ‘Achieving sustainable cultivation of bananas, Vol 1. Cultivation techniques. Eds. GHJ Kema, A Drenth. Burleigh Dodds Scientific Publishing: Cambridge UK. 2018, pp. 93-116.

- Turner DW, Gibbs DJ, Ocimati W, Blomme G. The suckering behaviour of plantain (Musa, AAB) can be viewed as part of an evolved reproductive strategy. Scientia Horticulturae 2020, 261, 108975. [CrossRef]

- Turner DW, Hunt N. ‘Growth, yield and nutrient composition of 30 banana varieties in subtropical New South Wales’. Technical Bulletin 31, Department of Agriculture NSW, Sydney. 1984.

- Turner DW, Hunt N. Planting date and defoliation influence the time of harvest of bananas. Scientia Horticulturae 1987, 32, 233-248. [CrossRef]

- Twyford IT. Banana nutrition: a review of principles and practice. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 1967, 18, 177-183. [CrossRef]

- White PR. Studies on the banana. An investigation of the floral morphology and cytology of certain types of the genus Musa L. Zeitschrift. Fuer. Zellforschung und Mikroskopische Anatomie Bd. 1928, 7, 673-733. [CrossRef]

- Yockteng R, Almeida AMR, Morioka K, Alvarez-Buylla ER, Specht CD. Molecular evolution and patterns of duplication in the SEP/AGL6-like lineage of the Zingiberales: a proposed mechanism for floral diversification. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2013, 30, 2401-2422. [CrossRef]

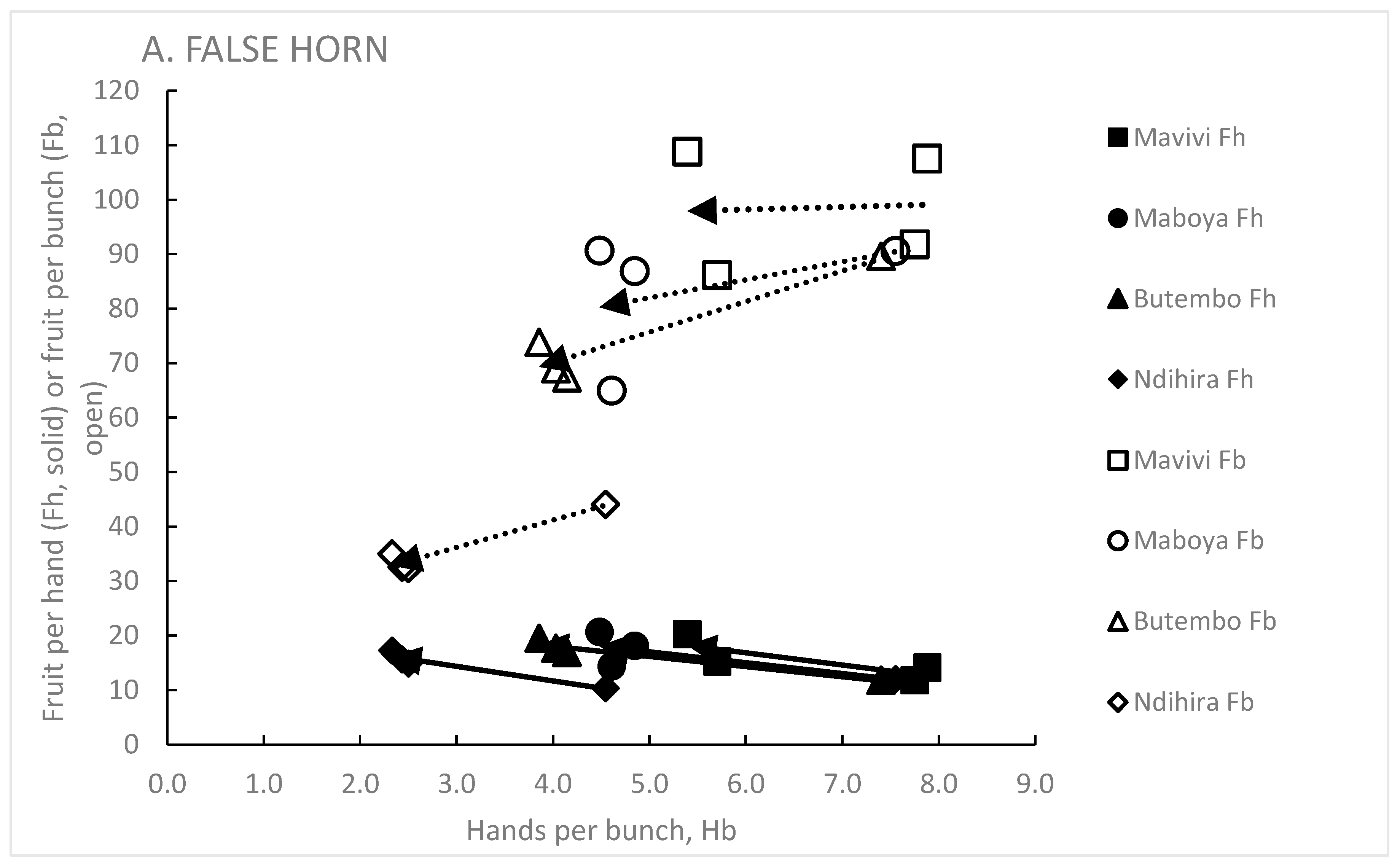

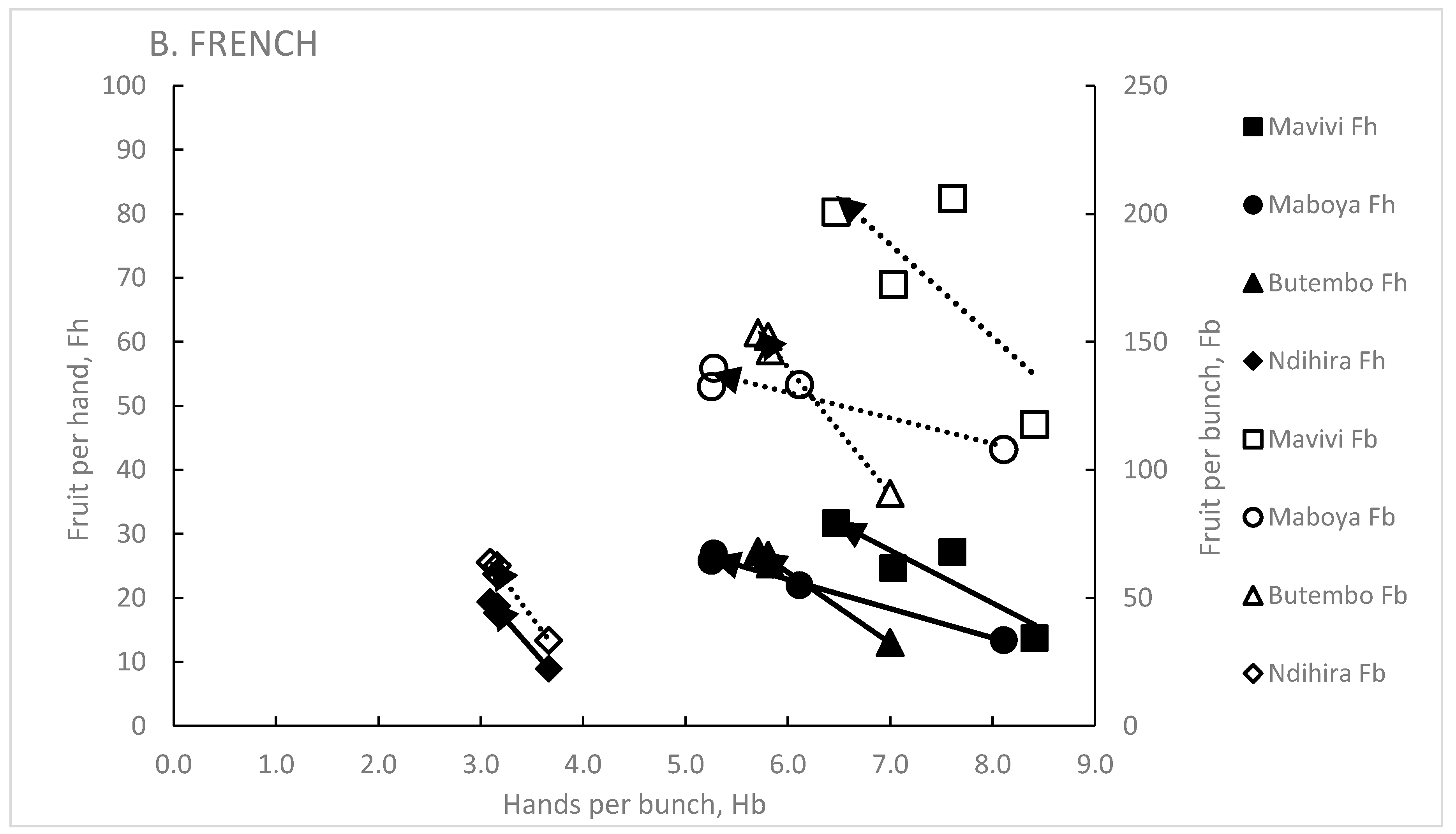

| Parameters of the female peduncle | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Hands/bunch, Hb | ||||

| Clone set | False Horn | French | |||

| Site/Cultivar | ‘Kotina’ | ‘Vuhembe’ | ‘Musilongo’ | ‘Nguma’ | ‘Vuhindi’ |

| Mavivi, 1066 m | 5.29 | 4.67 | 5.57 | 5.42 | 5.63 |

| Maboya, 1412 m | 3.69 | 3.73 | 3.91 | 4.73 | 4.67 |

| Butembo, 1815 m | 3.60 | 3.49 | 4.73 | 5.86 | 4.73 |

| Ndihira, 2172 m | 2.12 | 2.04 | 2.36 | 2.07 | 1.94 |

| LSD, P=0.05 | 0.23 | ||||

| Parameter | Fruit per hand, Fh | ||||

| Mavivi | 11.8 | 14.4 | 20.2 | 24.1 | 21.8 |

| Maboya | 14.6 | 13.9 | 21.9 | 20.9 | 17.2 |

| Butembo | 17.4 | 14.6 | 21.6 | 24.2 | 24.4 |

| Ndihira | 2.6 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 3.5 |

| LSD, P=0.05 | 0.2 | ||||

| Parameter | Fruit per bunch, Fb | ||||

| Mavivi | 58.8 | 65.7 | 110.8 | 127.4 | 120.2 |

| Maboya | 52.9 | 50.4 | 83.1 | 97.1 | 79.0 |

| Butembo | 59.8 | 49.5 | 100.3 | 139.2 | 113.3 |

| Ndihira | 5.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 5.5 | 5.9 |

| LSD, P=0.05 | 1.3 | ||||

| Dimensions of the reproductive peduncle | |||||

| Parameter | Length of reproductive peduncle, Pr, cm | ||||

| Cultivar | ‘Kotina’ | ‘Vuhembe’ | ‘Musilongo’ | ‘Nguma’ | ‘Vuhindi’ |

| Mavivi | 128 | 95 | 143 | 148 | 142 |

| Maboya | 78 | 80 | 121 | 141 | 111 |

| Butembo | 109 | 95 | 137 | 159 | 132 |

| Ndihira | 107 | 130 | 105 | 100 | 107 |

| LSD, P=0.05 | 3 | ||||

| Parameter | Female proportion of reproductive peduncle, Pf, % | ||||

| Mavivi | 74 | 74 | 57 | 66 | 60 |

| Maboya | 73 | 69 | 52 | 61 | 56 |

| Butembo | 70 | 66 | 58 | 59 | 57 |

| Ndihira | 22 | 17 | 26 | 26 | 18 |

| LSD, P=0.05 | 1 | ||||

| Site | Mavivi | Maboya | Butembo | Ndihira |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site Temperature, °C | 23.5 | 21.4 | 18.8 | 16.1 |

| Data/parameter | Hands/bunch, Hb | |||

| Measured | 5.31 a | 4.15 b | 4.48 c | 2.11 d |

| SQRT(PK) | 6.75 a | 5.19 b | 5.07 c | 3.00 d |

| SQRT(PK), Ndhi calc | 6.75 | 5.19 | 5.07 | 2.86 |

| Parameter | Fruit/hand, Fh | |||

| Measured | 18.3 a | 17.6 a | 18.9 b | 2.8 c |

| SQRT(PK) | 23.3 a | 22.0 b | 23.1 a | 3.0 c |

| SQRT(PK), Ndhi calc | 23.3 | 22.0 | 23.1 | 17.6 |

| Parameter | Fruit/bunch, Fb | |||

| Measured | 97 a | 73 b | 92 c | 5.5 d |

| PK | 156 a | 113 b | 118 c | 6.3 d |

| PK, Ndhi calc | 156 | 113 | 118 | 52 |

| Parameter | Total peduncle length, Pr, cm | |||

| Measured French | 144a | 125b | 143a | 104c |

| Measured False Horn | 112d | 79e | 102c | 118f |

| SQRT(PK) French | 183a | 156b | 162c | 111d |

| SQRT(PK) False Horn | 142e | 99f | 115d | 127g |

| Clone set | A | Tb, °C | Curvature coeff, C | r | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hands per bunch, Hb | |||||

| French | 6.98 A | 15.1 | -0.81 A | 0.75 | *** |

| False Horn | 20.1 B | 5.0 | -22.78 B | 0.87 | *** |

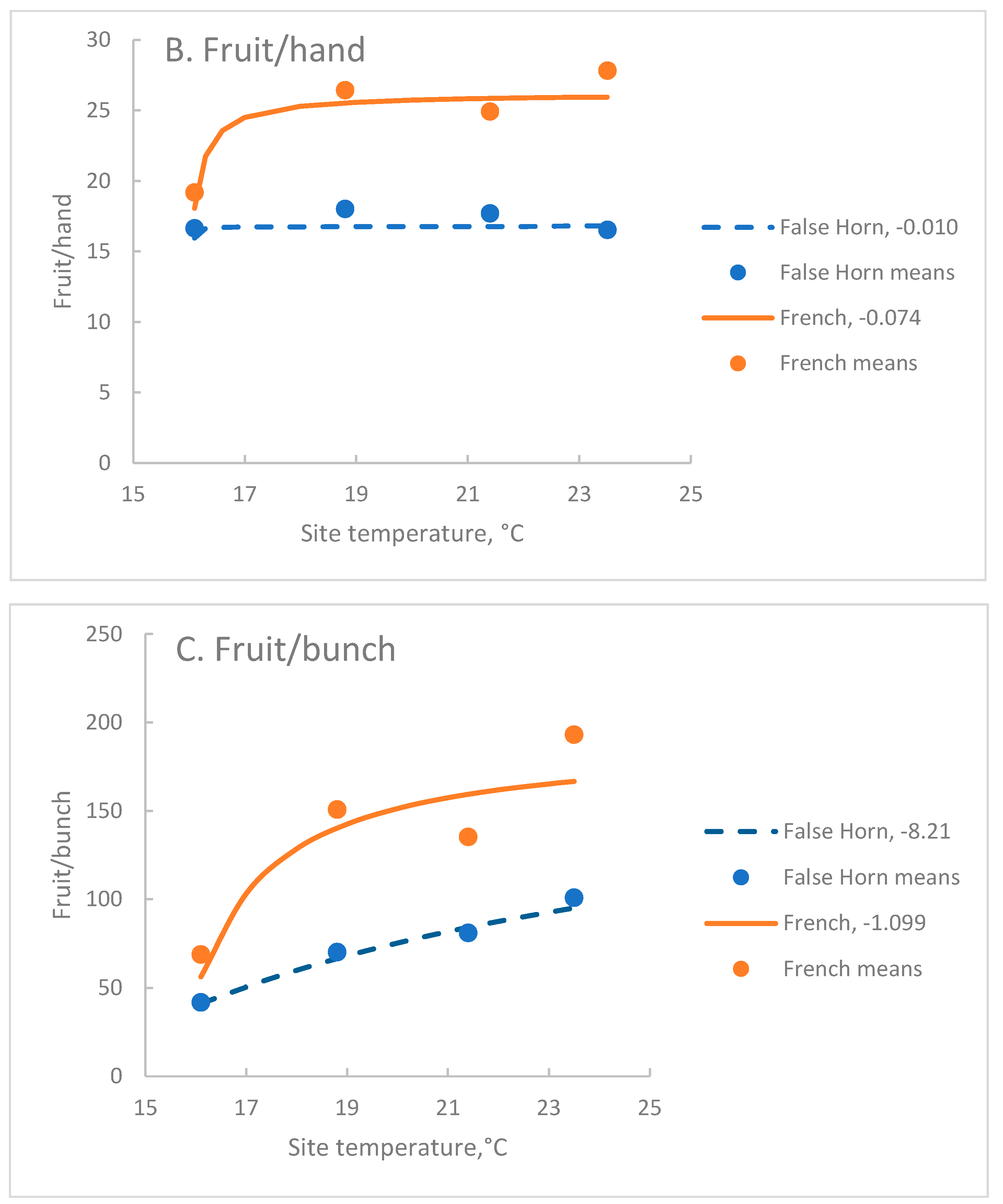

| Fruit per hand, Fh | |||||

| French | 26.2 A | 15.9 | -0.074 B | 0.51 | *** |

| False Horn | 16.8 B | 15.9 | -0.010 C | 0.08 | 0.097 |

| Fruit per bunch, Fb | |||||

| French | 190 A | 15.2 | -1.09 B | 0.74 | *** |

| False Horn | 179 B | 10.5 | -8.21 C | 0.83 | *** |

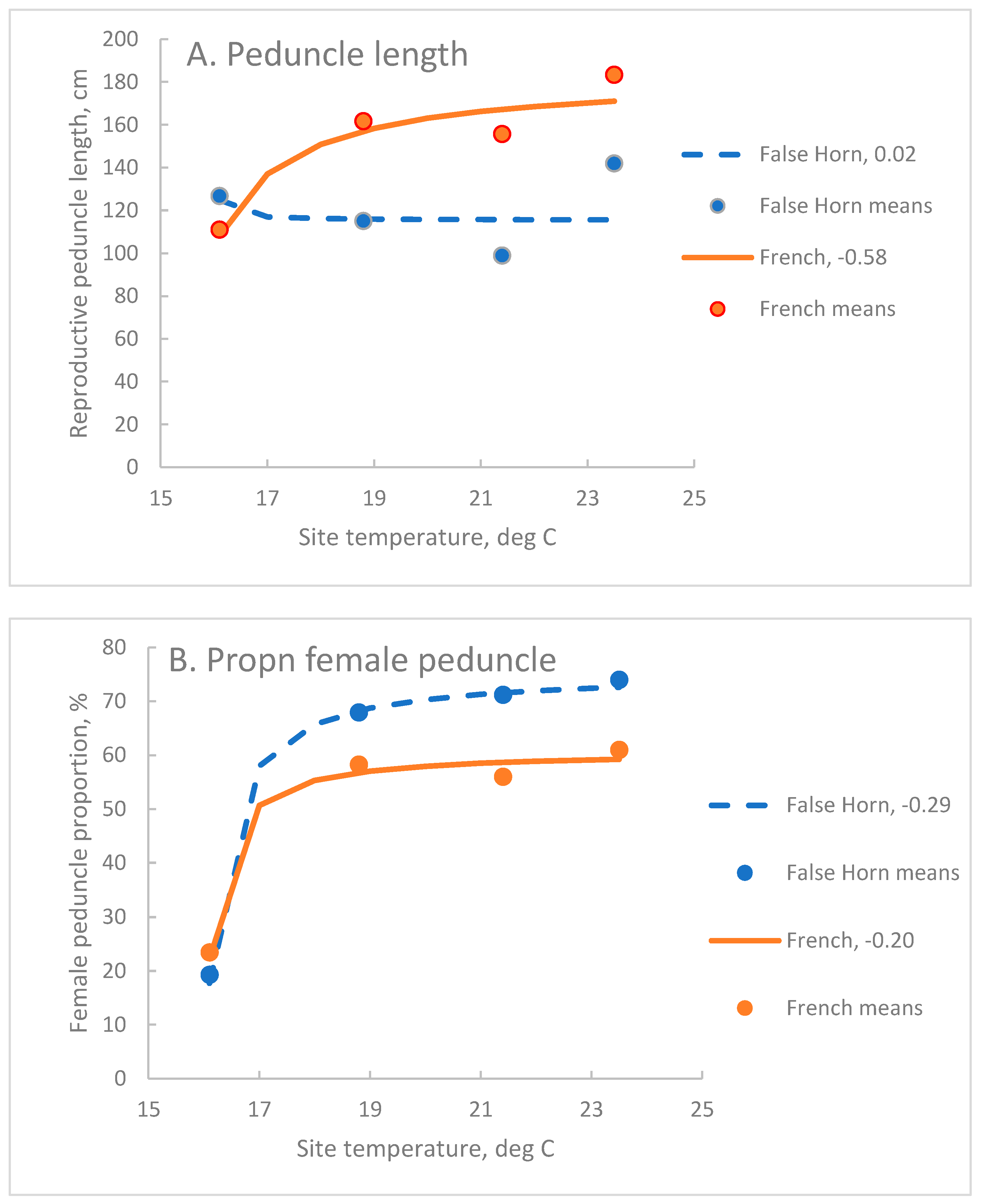

| Length of reproductive peduncle, Pr, cm | |||||

| French | 183 B | 15.0 | -0.581 B | 0.73 | *** |

| False Horn | 115 C | 15.9 | -0.016 C | 0.16 | 0.001 |

| Proportion of peduncle with female flowers, Pf | |||||

| French | 60.8 A | 15.9 | -0.201 B | 0.92 | *** |

| False Horn | 75.5 B | 15.9 | -0.290 C | 0.94 | *** |

| Site, Temperature, °C | Hands/bunch, Hb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Rate-1 | Days to produce Hb | |||

| French | False Horn | Days/hand | French | False Horn | |

| Mavivi, 23.5 | 6.34 | 5.87 | 1.64 | 10.4 | 9.6 |

| Maboya, 21.4 | 6.14 | 5.01 | 2.13 | 13.1 | 10.7 |

| Butembo, 18.9 | 5.64 | 3.90 | 3.33 | 18.8 | 13.0 |

| Ndihira, 16.1 | 3.11 | 2.58 | 5.26 | 16.4 | 13.6 |

| Flowers/hand, Fh | |||||

| Observed | Rate-1 | Flowers/day | |||

| French | False Horn | Days/cincinnus | French | False Horn | |

| Mavivi, 23.5 | 25.9 | 16.8 | 11.4 | 2.27 | 1.47 |

| Maboya, 21.4 | 25.8 | 16.8 | 14.9 | 1.73 | 1.13 |

| Butembo, 18.9 | 25.6 | 16.7 | 23.2 | 1.10 | 0.72 |

| Ndihira, 16.1 | 18.1 | 16.0 | 35.4 | 0.51 | 0.45 |

| Genome (n) | Increase in fruit/hand, Fh, % | Increase in hands/bunch, Hb, % |

|---|---|---|

| AAA (17) | 60 | 15 |

| AAB + ABB (7) | 23 | 16 |

| Cultivar | Ndhi ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fh | Hb | Fb | |

| ‘Kotina’ | 0.97 | 0.60 | 0.58 |

| ‘Vuhembe’ | 0.87 | 0.71 | 0.62 |

| ‘Musilongo’ | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.17 |

| ‘Nguma’ | 0.85 | 0.70 | 0.60 |

| ‘Vuhindi’ | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).