1. Introduction

The most controversial aspect of quantum theory is the apparent contradiction between the nature of its predictions and the existence of an objective microscopic reality [

1,

2]. The only accepted way to produce observer-independent ontological models is by rejecting other principles of classical physics, such as locality and/or freedom of choice with regard to measurement settings [

3]. This is not “just a philosophical concern”, because the mentioned contradiction is supported by a very strong formal argument (Bell’s Theorem [

4]) and several decades of rigorous experimental work [

5,

6,

7,

8]. In particular, a series of loophole-free experiments have been designed and successfully conducted [

9,

10,

11,

12], such as to verify the relevance of three ontological assumptions for quantum behavior. The first condition is known as “Realism” and corresponds to the statistical concept of joint distribution. It is based on the famous argument of Einstein, Podolsky and Rosen (EPR) [

13], suggesting that quantum properties must be real before the act of measurement. This simultaneous existence makes them amenable for analysis with classical (Kolmogorov) probability theory. The second condition is known as “Locality” and corresponds to the statistical concept of conditional independence. It was defined by Bell [

4] as a criterion for physical independence. In plain language, when Alice and Bob make parallel observations, detectable outcomes of Alice cannot depend on the choice of measurement by Bob (and vice versa). Instead, their correlations must be explained by hidden variables. This is why loophole-free experiments are designed with “space-like separated” measurement stations. The third condition is known as “Free Will” and corresponds to the absence of statistical correlations between measurements choices and the hidden variables that produce correlations. As formulated by CHSH [

14], the reasoning behind this criterion is that Alice and Bob should not be able to distort the underlying physical reality with restricted patterns of joint observation. This is why modern loophole-free experiments use random-number generators for measurement choices.

These three conditions are rigorously defined, from a mathematical point of view. Unfortunately, their ontological content is far from definitive. In particular, the formulation of Realism is limited to physical properties that exist (or can be recorded) at the same time. This constraint is unjustified, because mutually exclusive properties can also be real. Contrary to Bohr [

15], there is no conflict between contextuality and classical physics [

16,

17,

18,

19]. For example, the arrow of an analogue clock can point in different directions at different points in time. We only observe “1 o’clock” (or “2 o’clock”, “3 o’clock” etc.) when the conditions for its manifestations are satisfied, yet the underlying mechanism is perfectly real in an observer-independent fashion. The side-effect of this limitation is that the Locality Criterion is also ill-defined, from an ontological point of view. In particular, Bell’s Theorem appeared to rule out the possibility of pairwise consistency between alternative joint measurements (i.e., for Alice’s value to be the same, regardless of Bob’s choice of measurement), if quantum theory is correct. Yet, this prediction is at odds with the non-signaling principle [

20]. Indeed, “quantum-like” and “super-quantum” correlations with pairwise consistency are also possible in classical systems, as will be shown below. Finally, the Free-Will criterion cannot distinguish between remote and local alternative settings. It turns out that local mechanisms can produce the markers of statistical dependence without restricting the freedom of observation in any ontologically meaningful way.

The fundamental inconsistency between classical and quantum mechanics is mathematical. Some properties are compatible and require phase spaces for analysis. Other properties are incompatible and require Hilbert spaces. The question is: do we not have classical behavior in both cases? The current practice is to reject this possibility, as if Hilbert spaces demand non-classical ontologies. Yet, as will be shown below, “non-classical” properties are very common in our everyday life. Simply by looking at the properties of a spinning arrow, we can observe “super-quantum” correlations, far beyond the scope of entangled quanta. More importantly, these patterns emerge as part of single systems, without any room for doubt about their “locality” or “realism”. Accordingly, the challenge is not to defend the accuracy of quantum predictions, but rather to justify the need for dramatic interpretive conclusions. When new phenomena are discovered, classical mechanics is not necessarily falsified. Just as likely, it is expanded.

2. Materials and Methods

Quantum entanglement was officially discovered by EPR, as a thought experiment. Their stated intent was to illustrate a reasonable Reality Criterion [

13]. If Alice measured a quantum property, she could predict with certainty the outcome of an identical measurement by Bob (provided that the two quanta were suitably correlated). The same would hold for any other choice of measurement by Alice, even if Bob did not perform a measurement. Therefore, all the unmeasured properties of Bob’s quantum should be treated as real at the same time,

as part of a single system. A similar idea is latent in the derivation of Bell’s theorem, where joint probabilities are defined for classical models of reality [

4]. What happens when all the observables exist at the same time, as part of a single system? The answer is that Bell violations are impossible. This gives us a platform for thinking about correlated remote measurements. Alice gets the same result as Bob for property 1 and for property 2. If they measure different properties, they simply confirm what would happen if both measurements were done on the same system. This is how we know that Alice and Bob events are physically independent, despite their statistical dependence, if Bell’s inequality is obeyed. In the same way, if we knew that Bell violations were locally possible, as part of a single system, then identical patterns for remote joint measurements would not require additional explanations.

When physical properties exist at the same time, they can be detected at the same time. Yet, when such properties are mutually exclusive, this is no longer possible. The only way to detect coincidences between sequential properties, as part of a single system, is by allowing for measurement schemes with extended windows of coincidence. For example, the arrows of an analogue clock can point in every possible direction, in sequence, but only one at a time. If the arrow points to 1 o’clock, then it is not pointing to 2 o'clock, and so on. Accordingly, it is possible to isolate consecutive events in pairs, if the window of coincidence is wide enough to include two events, but not wide enough to include three or more. Remarkably, a chain of pairwise connections on a clockface must close back on itself. This is convenient, because a Bell-type experiment is also a closed chain of pairwise measurements, such that any single variable is measured in coincidence with two others. So, let us attempt to replicate a CHSH experiment with staggered properties in a “clockwork” classical system.

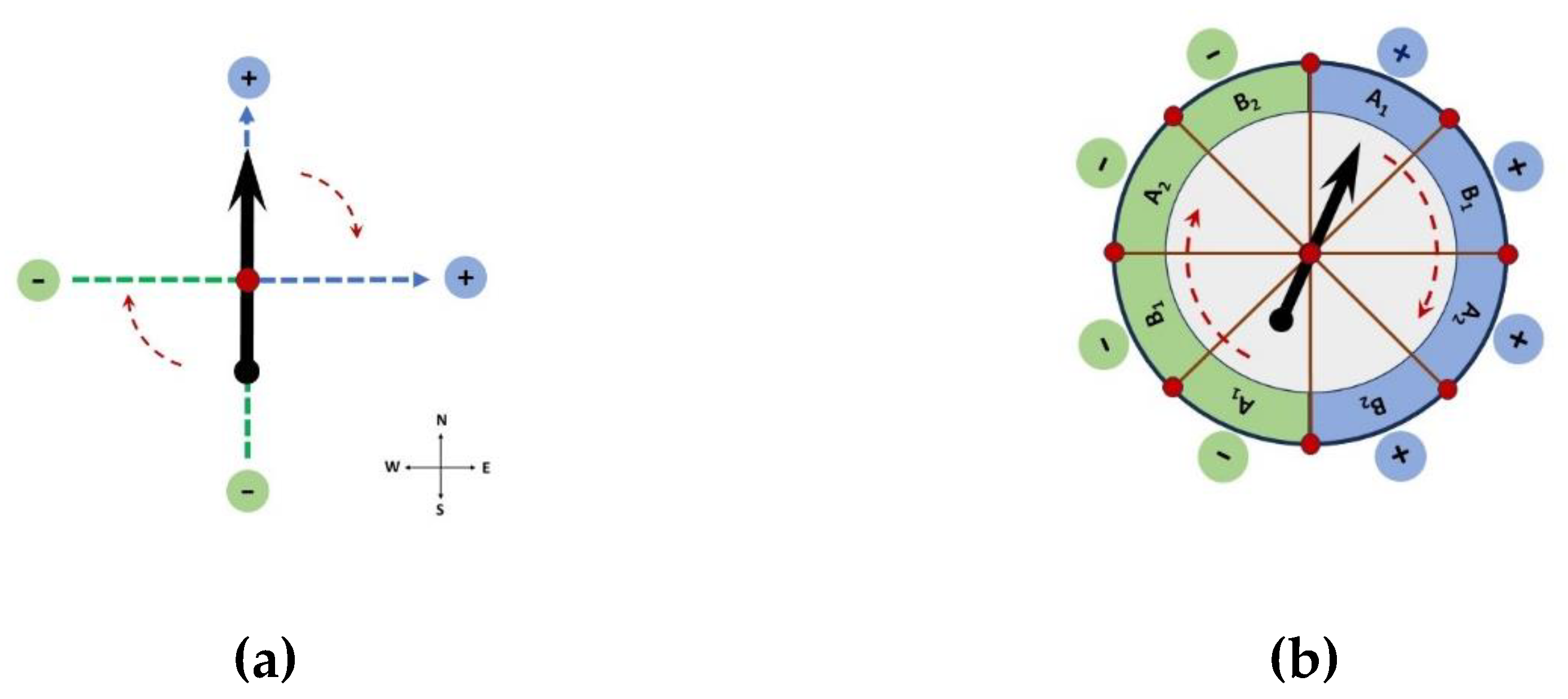

Consider a large (classical) object in the shape of an arrow, rotating above a table with printed markers. Any imaginary axis through the center of the table is crossed by the arrow twice per full rotation. Accordingly, it is possible to assign binary values to opposite ends of each axis, such as “+” for North and “−” for South, or “+” for East and “−” for West (

etc.), as shown in

Figure 1a. The “outcomes” for each axial variable must exhibit 50-50 distributions, as long as the arrow is moving continuously. The CHSH protocol requires 4 binary variables. Therefore, it is possible to replicate a Bell setting with four suitably arranges axes. For clarity, the surface of the underlying table can be divided into 8 sectors, as shown in

Figure 1b.

A1 and

A2 values are interlaced with

B1 and

B2 values, in order to enable the pair-wise detection of all the necessary combinations for a Bell test. If the arrow is forced to rotate at a fixed rate, by means of an actuator, it passes over each sector, one at a time. If the arrow is in the state of hovering over sector “

A1+”, then we can describe this observation as a “conditional real outcome”. The same rule applies to all the other sectors, in sequence, resulting in a simple toy model with contextual classical properties.

Figure 1.

Classical system with sequential binary properties. A macroscopic arrow is forced by a clockwork mechanism to rotate at a constant rate. (a) A full rotation produces two passages over each axis, as shown in the background. The opposite ends of each axis can be marked with binary values, such as “+” or “−”. (b) A CHSH arrangement can be produced by dividing the background plane into 8 sectors, containing the ordered measurement outcomes for the 4 relevant observables. It is possible to make two copies of this system, one for Alice and one for Bob. Yet, the value of this example is to illustrate the relationships between these 4 variables as part of a single system. Each observable “becomes real” when the arrow passes above the corresponding sector. Maximal Bell violations emerge if pairs of events are detected in coincidence windows that include only two events at a time.

Figure 1.

Classical system with sequential binary properties. A macroscopic arrow is forced by a clockwork mechanism to rotate at a constant rate. (a) A full rotation produces two passages over each axis, as shown in the background. The opposite ends of each axis can be marked with binary values, such as “+” or “−”. (b) A CHSH arrangement can be produced by dividing the background plane into 8 sectors, containing the ordered measurement outcomes for the 4 relevant observables. It is possible to make two copies of this system, one for Alice and one for Bob. Yet, the value of this example is to illustrate the relationships between these 4 variables as part of a single system. Each observable “becomes real” when the arrow passes above the corresponding sector. Maximal Bell violations emerge if pairs of events are detected in coincidence windows that include only two events at a time.

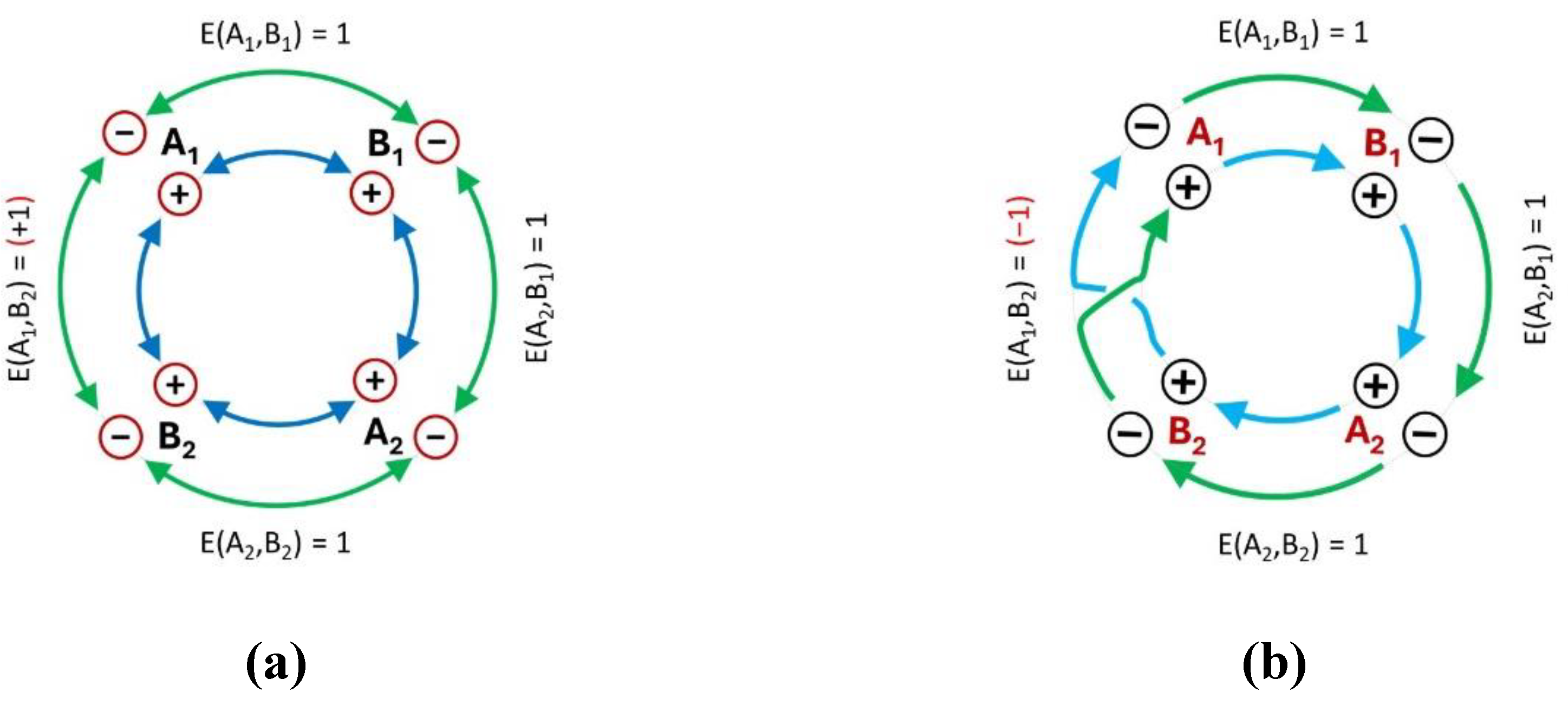

A well-known feature of quantum entanglement is that Bell violations happen for pairwise measurements (and only for pairwise measurements [

21]). Such patterns are not possible for systems with jointly distributed variables. For example, as shown in

Figure 2a, maximally correlated simultaneous properties exist in homogeneous quadruplets. Objectively, all the four observables have “+” values, or all of them have “−” values, depending on which iteration is chosen. Hence, pairwise detections cannot do more than sample this underlying pattern. The outcome is a set of Kolmogorov -compatible set of coefficients of correlations. The CHSH inequality for this case is:

Given that all the pairs are maximally correlated, and that all the expectation values are equal to 1, we get:

Figure 2.

Coincidence patterns for simultaneous vs sequential properties. Jointly distributed variables can only have compatible coefficients of correlation. This rule does not extend to mutually exclusive (but still objective) properties. (a) Simultaneous realism entails that all the variables express their values at the same time, for each object. In a population with maximal correlations, each object is either represented by the green circle, or the blue circle. Pairwise observations sample this pattern and cannot violate the CHSH inequality. (b) Sequential realism enables the pairwise detection of two observables at a time, with no regard for the state of other properties. The same Möbius-strip pattern is replayed over and over. Both loops must be traversed in full before returning to the same starting point. Maximal CHSH violations emerge, as explained in the text.

Figure 2.

Coincidence patterns for simultaneous vs sequential properties. Jointly distributed variables can only have compatible coefficients of correlation. This rule does not extend to mutually exclusive (but still objective) properties. (a) Simultaneous realism entails that all the variables express their values at the same time, for each object. In a population with maximal correlations, each object is either represented by the green circle, or the blue circle. Pairwise observations sample this pattern and cannot violate the CHSH inequality. (b) Sequential realism enables the pairwise detection of two observables at a time, with no regard for the state of other properties. The same Möbius-strip pattern is replayed over and over. Both loops must be traversed in full before returning to the same starting point. Maximal CHSH violations emerge, as explained in the text.

In contrast, sequential properties are not limited in the same way. Instead, a full cycle includes all the 8 possible observations in a closed chain, resulting in a Möbius-strip pattern, as shown in

Figure 2b. The net effect is a combination of statistically incompatible coefficients. Three pairs of observables can only coincide with (+,+) or (−,−) outcomes, making them maximally correlated. In contrast, one pair is only able to coincide with (+, −) or (−,+) outcomes, due to the double crossover between the inner and the outer loops of the Möbius strip (

Figure 2b). This makes it maximally anti-correlated. When plugging these values in the CHSH expression, we get:

Such a mixture of pairwise combinations is logically impossible for jointly distributed variables. Nonetheless, it emerges naturally in a system with sequential properties. We have a classical mechanism that operates like a clock, whether or not it is observed. All the values are printed on the table and cannot change just because the arrow is passing over them, or because a person is looking at them. Each transient outcome is flanked by two different sectors on the table. So, pairwise consistency is maintained throughout, meaning that distributions (A1, B1) and (B1, A2) always agree about the values of B1, while (B1, A2) and (A2, B2) always agree about the values of A2, etc. Surprisingly, a maximal Bell violation was produced anyway.

If such behavior is possible for a single system, then it can also happen for correlated copies of the same system. This is self-evident. As a result, non-signaling and local behavior must be described as physically equivalent. In other words, the expression

does not describe just the

average probability that Alice might observe the same outcome for both settings of Bob. It is actually possible for

every one of Alice’s events to be exactly the same, no matter what Bob does. Accordingly, it is not meaningful to suggest that entangled quanta influence each other directly in hidden-variable models. Statistical separability is just a consequence of statistical compatibility. If relevant variables are not jointly distributed, then their joint probabilities are not separable. The “non-classical” implications of this relationship are not so clear, given its demonstration in a classical system.

3. Results

Theoretical physics is famous for its rigorous precision. Not surprisingly, even abstract concepts like “Realism”, “Locality” and “Free Will” enjoy precise mathematical definitions in quantum mechanics. However, it is not enough to have quantitative accuracy. When studying ontological subtleties of unobservable entities, qualitative exactitude is just as important. If we are going to question the fundamental existence of reality, shouldn’t we have good reasons for that? In other words, if we are going to draw conclusions about the outside world on the basis of mathematical arguments, shouldn’t our mathematical constructs correspond to the philosophical categories that they claim to represent? As will be shown below, it is not possible to map quantitative Realism to qualitative Realism in modern physics, and the same is true for the other two conditions of Bell’s argument, namely Locality and Free Will.

3.1. Realism vs Realism

In the context of quantum entanglement, the notion of

Realism is defined as the principle that different measurement outcomes can be described by two families of random variables:

Yet, this apparent simplicity of notation conceals a complex theoretical construct, including a sample space with hidden variables and a system of rules for mapping the elements of this space to expected measurement outcomes [

3]. The most important feature of this definition of Realism is that measurement outcomes are amenable to analysis with classical (Kolmogorov) probability theory. In other words, we assume a Universe in which all the observable properties of quantum mechanics correspond to physical properties that exist at the same time, in the absence of measurement, as part of a single system. This is why the corresponding variables are expected to be jointly distributed.

Contradiction #1: According to this definition, an objective “clockwork” Universe must only include permanent unconditional properties. Yet, as shown above, the most useful feature of a clock is the ability to display conditional properties one at a time. (It must show the time of the day). Just because some properties are mutually exclusive, it does not follow that the Universe is less “real”. Yet, such observables cannot be accurately described with jointly distributed variables. For the same reason, they cannot be expected to obey Bell-type inequalities. The mathematical definition of “Realism” does not convey the full ontological meaning that it was supposed to capture.

3.2. Locality vs Locality

Debates about quantum entanglement employ two different meanings of “non-locality”. As defined by Bell [

4], locality is equivalent to conditional separability in statistical analysis:

This expression is

also anchored in classical probability theory, and therefore requires joint distributions for validity [

22]. In other words, Bell violations are markers for “signaling non-locality” in the context of hidden variable models. Pre-existing values must “flip” in response to remote choices, like telegraphs, or else violations are impossible. Ergo, the non-signaling condition (4) is implicitly violated. However, we also know today that non-signaling behavior can happen for maximal Bell violations [

20], if the “Realism” condition is violated. Accordingly, quantum correlations must be described as “non-local” in a different way. Non-commuting properties are mutually exclusive. According to the Copenhagen interpretation, each measurement is the result of local “wave-function collapse”. Yet, a “local collapse” for Alice’s quantum must also induce a “non-local collapse” for Bob’s quantum, due to entanglement. The caveat is that “non-locality” must also be “non-signaling” in this case, such that Alice’s outcome is always the same for any choice by Bob (and vice versa). To sum up, “realist” models achieve non-locality by flipping the values of permanent properties

without pairwise consistency, while “non-realist” models express non-locality via remote emergence of contextual properties

with pairwise consistency.

Contradiction #2: The Möbius pattern, presented above, displays maximal Bell violations with pairwise consistency. Therefore, it contradicts the separability condition, associated with Bell locality. Moreover, all the combinations emerge from a clockwork mechanism, as part of a single system. There is no reason to invoke local collapse for single events, or non-local collapse for synchronized correlated arrow systems. A formal contradiction with “Locality”, as defined in this context, does not justify the need to invoke ontological non-locality.

3.3. Free Will vs Free Will

The “Free Will” condition is controversial in modern physics, because it is unverifiable in some super-deterministic scenarios [

23]. Nonetheless, such proposals entail esoteric aspects with debatable relevance, at least at the moment. Therefore, the practically established criterion in this case is to satisfy the requirement of “experimental freedom” with random measurement settings. As stated by CHSH in their notorious paper, “

we assume that the normalized distribution ρ(λ) characterizing the ensemble is independent of (adjustable parameters) a and b” [

14]. The well-known concern here is that a local hidden variable model can produce Bell violations if the so-called “detection loophole” is not closed [

3,

24]. In particular, observable statistics may distort the underlying reality if measurement settings are correlated with the hidden parameter

λ. This is why it is important to demonstrate the ability of Alice and Bob to choose their measurement settings independently, for example by employing separate random number generators.

Contradiction #3: This “loophole argument” is tightly connected to the formal definition of Realism, in terms of compatible properties. Accordingly, it is mathematically possible to treat a Mobius strip pattern as a system of jointly distributed variables. Yet, this would entail that Bell violations emerge from the strong correlation between hidden variables and measurement settings. The problem is that such a treatment distorts the actual physics of the proposed model. In particular, we are dealing with a deterministic system that is explicitly designed not to express simultaneous properties. The crucial feature of this demonstration is that everything happens as part of a single system. The pattern of detection is fixed, but this is due to an objective internal mechanism. There are no “measurement artifacts” in this model. Hence, the formal definition of “Free Will” can be violated without any concern about the ability to capture the true underlying reality.

To sum up, it is possible to contradict all the formal parameters of Local Realism, as defined for a Bell experiment, while observing a system that is unquestionably Local and Real. Quantum theory is correct, and its predictions are valid, but currently accepted interpretations cannot be justified.

4. Discussion

Quantum entanglement was discovered as part of a debate about physical reality. The problem was that classical formal models (with unconditional properties) did not work at the microscopic level. Quantum observables were known to be conditional. They only emerged in “measurement contexts”, where they had to be prepared with suitable devices and then recorded with detectors. Surprisingly, Bohr decided to ignore the physical significance of preparation, suggesting that detection alone is the essence of contextuality. Instead of an objective material Universe, he advanced an “observer-dependent” model of reality. In response, EPR came up with a Reality Criterion that falsified the fundamental role of observation. When physical properties are predictable with certainty, in the absence of measurement, they have to be treated as real. Such predictions are possible with strongly correlated systems, even for non-commuting variables. Unfortunately, EPR did not use their argument to shift the attention back to the act of preparation. They could have said, for example, that Alice measures a contextual property. Therefore, her predictions about Bob are also conditional on Bob’s decision to make an identical preparation. Instead, they implied that Alice’s phenomena are unconditional (and therefore Bob’s observables are also unconditional). They ended up defending a model of reality with permanent properties, as if preparation again did not matter. In short, they tried to recover the relevance of classical probability theory for quantum phenomena. As a result, they cemented the relevance of old models that did not work, with an apparent contradiction between Realism and quantum theory.

The goal of physics is to study the world as it is. Accordingly, physicists are rarely comfortable with “anti-realism”. Instead, they seem to be drawn to alternative explanations. Maybe the world is nonlocal? Maybe it is super-deterministic? Maybe it is retro-causal? The lost detail is that Realism, as formally defined, includes just a narrow slice of reality. It only contains permanent unconditional properties – the kind that can fit in Kolmogorov probability models without contradictions. As shown above, the other assumptions for Bell’s inequality are also dependent on such expectations about probability theory. In particular, the Locality criterion and the Free Will criterion can only be derived as consequences of Simultaneous Realism. Everything is stacked on the same foundation, layer by layer. In retrospect, it is unnecessary to limit Realism to jointly distributed variables. Classical systems can undergo alternative contextual transformations with “quantum-like” correlations, or they can have programmable sequences of properties with “super-quantum” correlations. As shown above, programmable staggered events can display objective properties with unquestionable locality, even though the corresponding formal criteria are violated. In short, the problem is not that physical Realism is false. The problem is that wide ontological concepts are improperly mapped to narrow mathematical conditions.

In conclusion, there is no contradiction between quantum mechanics and Local Realism. Existing arguments to the contrary appear strong because of their logical consistency. They are also supported by hard evidence. Nonetheless, they are based on excessively narrow definitions. The mathematical expressions for “Realism”, “Locality” and “Free Will” do not capture the full ontological scope of these concepts. All of them are limited to properties that can be analyzed with classical probability theory. Unfortunately, this means that simultaneous observables alone are treated as “real”, at the expense of mutually exclusive phenomena. To clarify this issue, it was necessary to adopt a radically simple approach, by focusing on the properties of individual systems. If a single classical process can display maximal Bell violations, then quantum level violations cannot falsify Local Realism. Though, it should be noted that the “Möbius strip” model, as discussed above, was developed for conceptual purposes and is not intended to explain the actual details of quantum entanglement. This concern is deliberately omitted in this text, to avoid confusion, and will be addressed in a separate article. Similarly, the problem of Realism in the context of classical physics is another topic that was ignored for too long [

25], but it needs to be discussed in a different venue.