1. Introduction

In recent years, with the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms, computing capacities, data models, interpretable AI, and related methods have been nourishing tremendous products in the domain of medical imaging, especially in the field of malignant tumor diagnosis and treatment. Cervical cancer, endometrial cancer, and ovarian cancer represent three major types of gynecological malignant tumors, where the global incidence rate is increasing year by year and displays the prevalent incidence of diseases with a younger trend in mainland China [

1].

In the medical domain, the contemporary study of gynecological tumors represents a very specific branch, which comprises a variety of topics such as disease prevention and control, early-stage screening and detection, the distribution of diseases, genetic testing, human data analysis, diagnosis, and treatment, to name a few. Those aspects have close intersections with explainable AI, which are gradually established on the foundations of big data, cloud computing, and deep learning-related approaches, indicating potential advantages on significant contributions to cancer screening and medical treatments.

As a communication article oriented for the state-of-the-art approaches, this paper mainly presents challenges and advances in explainable AI and current progress with big data, deep learning, radiation diagnosis, and treatments, providing referrable evidence and innovative ideas for the latest research on AI in the field of gynecological oncology.

2. Approaches and Methods

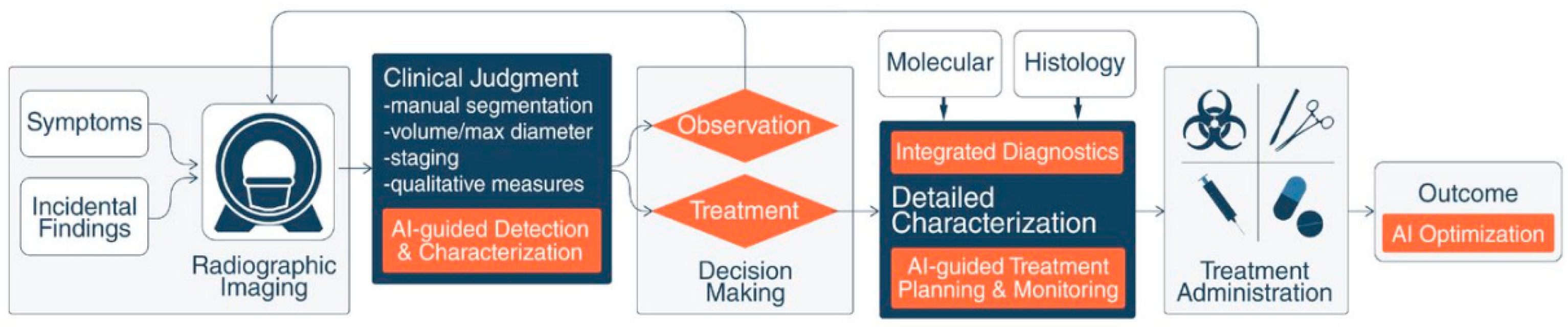

In general, an explainable AI-assisted clinical workflow consists of three modules [

2]: current practice, decision port, and “areas of impact” guided by AI. A workflow to enhance the standard of care for cancer patients is depicted in

Figure 1, where the block diagrams of current practice, decision port, and AI “areas of impact” are colored white, dark blue, and orange, respectively. Explainable AI provides auxiliary support to enhance this workflow and decision-making when diagnosing and treating cancers. Subsequently, the measured outcomes also generate feedback from patients and AI-based optimization for systematic improvement.

In gynecological malignant tumors, the links between explainable AI and big data mainly comprise early disease warning, medical imaging diagnosis and treatment, health management, genetic testing, and drug development [

3].

Take disease warning as the first example [

3]: it aims to discover correlations among multiple test results from patients, the present conditions of their disease, and medical outcomes from big data analysis, and then identify high-risk female patients with truly pre-cancerous potentials for invasive cancer and pre-invasive illness, referring them for medical referral, mandatory health monitoring, or providing them with personalized interventions and treatments in advance. While AI displays stronger capacities for data analysis and computation, it lacks emotions, self-awareness, and the ability to reflect on situations of one’s own [

3]. As a result, input information is just processed and analyzed with respect to manually designed computer programs. In a word, AI is still immature in quite a few aspects. Hence, appropriately explainable AI models and disease warnings demand crucial attention in preventing and treating gynecological malignant tumors.

In the last decade, crucial AI-based approaches and methods on the clinical use for gynecological tumors are summarized below:

An advanced neural network (NN) and AI technique-based clinical Decision Support Scoring System (DSSS) was developed by Kyrgiou et al. [

4], which exploits the capacities of all biomarker information on accurate prediction for which women display clinically significant lesions with true carcinogenic potential (CIN2 or worse), offering quantitative probabilities for different histological diagnosis.

Similarly, a neural network-based AI scheme was adopted by Pergialiotis et al. [

5], predicting endometrial cancer with an accuracy of 85.4% in 178 female patients with endometrial thickness of 5mm and post-menopausal vaginal bleeding.

The advantages of explainable AI on gynecological diagnosis are also oriented to skipping manual analysis while only requiring reviewed results from medical specialists [

3]. For diagnostic imaging, reliable AI techniques can reduce observer bias, alleviate the workload of doctors, and thereafter enable them to concentrate more on difficult cases, helping accurately identify rare diseases along with the quality of standardized reports [

2]. Therefore, it may significantly improve the efficiency of disease screening, overcome those errors due to the more vital subjectivity of manual diagnosis, and thereafter enhance the accuracy of diagnosis [

3].

In 2017, Bora et al. [

6] proposed a training and recognition framework for cervical atypical hyperplasia, which involves computer vision (CV) techniques for performing structured restructuring and analysis of cervical dysplasia, extracting key features of the lesion site, showing AI-based analysis of disease development, then proposing suitable plans for auxiliary diagnosis and treatments. Meanwhile, the classification and prediction of colposcopic images also benefit from the technical outputs of AI, which may effectively capture fine texture features and achieve higher diagnostic accuracy comparable to those achieved by medical experts [

7,

8].

While taking care of complicated gynecological tumors, AI usually offers guidance on clinical diagnosis and treatment in pre-operative imaging diagnosis: first, it predicts the presence of microvascular, lymph node metastasis, and nerve invasion lesions, then assists in designing personalized treatments; later, it helps to distinguish the benign and malignant conditions of the uterus and its attachments owing to the advantages from big data models [

9]. For pathological diagnosis, the differentiation of benign and malignant gynecological tumors, disease classification, and prognosis judgment are also dependent on automated histopathological image analysis [

10]. For instance, AI-aided screening for cervical cancers may demand technical output from automated detection on liquid-based cervical cell imaging [

11]. Besides, AI-based classifications between normal and CIN I-III features of cervical epithelial cells can be achieved by extracting kernel nuclear features or artificial biomarkers for nuclear images [

12].

AI-related clinical treatments for gynecological tumors are also broadly classified as surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, etc. [

3]. Currently, the most typical minimally invasive surgical method for gynecological tumors is undoubtedly robot-assisted surgery, represented by the Da Vinci robot, which consists of a surgical console, mobile robotic arm, and a three-dimensional (3D) imaging system. The main advantages of the Da Vinci Robot system are displayed with high magnification, high-definition stereoscopic field of view of 3D imaging, as well as higher surgical accuracy. Utilizing an intuitive motion control and a turning instrumental arm, the smart surgical system may perform more sensitive operations while filtering out tremors, hence increasing stability and safety. In contrast to traditional laparoscopic surgeries, due to less trauma, less bleeding, and fewer complications, which are capable of effectively alleviating post-operative pain, this AI-assisted system is suitable for ovarian cancer patients who have pretty strong demands to preserve fertility in the early stage [

13]. Besides, by creating images of virtual surgical sites, explainable AI-related deep images, and video processing may not only qualify for pre-operative planning, intra-operative navigation, accurate ablation of tumors and dissection of lymph nodes, etc. [

3], but also remotely control mechanical arms through the Internet to achieve telemedicine [

14].

In response to the potential drug resistance of gynecological malignant carcinoma cells in chemotherapy, AI has great potential for predicting the most effective anticancer drugs with their responses and continuously releasing the drugs to a concentration level above certain thresholds [

15]. For in-vivo targeted treatment of gynecological malignant tumors, AI mainly combines drugs through the functionalization of nano-robots, which points out cancer cells fast and accurately for later specific combination when enhancing the effectiveness of treatment; hence, the dosage of drug and potential side effects are decreased [

16]. Besides, while overcoming most drawbacks of poor penetration on intra-peritoneal infusion chemotherapy and its potential limitation on the surface of tumors, where AI-based computer-aided models incorporate their spatial heterogeneity, i.e., the distribution of capillary vessels and hydrophilicity, which may simulate spatial dynamics of available anti-cancer drugs, and enhance their capacities when penetrating towards the center area of tumor for treatment [

17].

In addition to those advances in surgical and chemotherapic treatments in the past few years, research progress in the field of gynecological malignant tumor radiotherapy also relies on the cooperative use of diagnostic imaging, big data, and explainable AI, which mainly focuses on some general workflows such as automatic delineation, dose and efficacy prediction, and adverse reactions to radiotherapy [

18]. Typically, deep learning-based approaches for the correlations of patient individual characteristics and dosimetry characteristics may automatically predict appropriate doses and develop radiotherapy plans. Besides, while improving the clinical practice of radiation oncology to develop precise, efficient, and optimized automated boundaries for three-dimensional (3D) space, both can be transplanted into the field of gynecological oncology [

19,

20]. Meanwhile, Saw et al. developed the Eclipse treatment planning software for the Varian Medical System to achieve intelligent design and dose optimization toward radiotherapy plans [

21].

However, applicable techniques for explainable AI, i.e., machine learning and deep neural networks for analyzing and treating gynecological tumors, are still in the research stage, which demands a certain number of experts on training image segmentation to meet advanced expectations of professional radiologists [

3,

18]. In the target area delineation of radiotherapy, typical AI advantages are efficiency, accuracy, good consistency, and strong standardization. For other organs at risk, AI shows delineation accuracy and good effects on segmentation. However, there is still a shortage of in-depth studies on designing radiotherapy plans, the fusion of imaging equipment, radiation toxicity assessment, and prediction of control rate on tumors. Take AutoPlan (Pinnacle platform, developed by Philip Inc. in the US) for a second example [

22]. As another relatively mature system for radiotherapy treatment on tumors, AutoPlan performs automatic planning in contrast to the emphasis on manual planning in the volume rotation of Eclipse. There are not only significant improvements in the conformability and uniformity of the target area in automatic planning but also an apparent reduction in organs at risk. It is imaginable that instead of merely relying on a few parameters, implementing deep learning models may replace prior indicators in clinical testing and achieve higher accuracy in personalized prediction. Meanwhile, while explainable AI-assisted delineations of the target area and their schematic planning currently still present limited applications in the diagnosis and treatment of gynecological malignant tumors, it only takes 25-40 minutes to achieve those tasks equivalent to traditional human labor of several hours, and after that improving the efficiency of both treatment planning and quality control, increasing benefits from those involved patients as well as reducing risks.

3. Recent Advances and Challenging Issues

In this section, recent challenges and advances in establishing recent diagnosis and treatment models for treating gynecological tumors are summarized, which may combine big data and AI for assisting clinicians in standardized operations, providing precise diagnosis and viable treatment, and contributing to personalized, safe, effective design for medical therapy and efficacy evaluation [

22]. We perform a concise study on a few representative challenging issues and recent progress (from the Year 2020 to the present) for explainable AI schemes and gynecological oncology, where a crucial summary of their work is presented below:

Tanabe et al. [

23] established a pre-trained CNN model AlexNet on recognizing early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) by adopting principal component analysis (PCA)-based 2D barcodes, where the diagnostic accuracy reached 95.1% of Receiver Operating Characteristics and Area Under Curve (ROC-AUC), reducing both financial stress and mental tension of patients when contributing to improving their survival rates. Later, a deep-learning-related mini-review on empowering the capacities of diagnosing diseases was proposed by Zhang et al. [

24], which promoted clinical decisions from representative studies among 19 different countries.

A computer-aided diagnosis (CADx) framework was proposed by Chen et al. [

25], performing self-supervised learning for in-vivo 3D OCT volumes from the cervix on screening cervical cancers and for cervical OCT image classification. This kernel strategy focused on contrastive learning for texture features from pre-trained convolutional neural network (CNN) models.

In Spring 2022, Lawton and Pavlik investigated eight major factors closely related to diagnosing ovarian cancer from 1809 to 2022 and beyond [

26].

AI-assisted colposcopy for cervical diagnostic pathology unit in a tertiary hospital was studied by Zimmer-Stelmach et al. [

27], evaluating the potential capabilities of this AI algorithm for correct identification of histopathology results of abnormal CIN2+, and then comparing clinical assessment results before and after using this scheme for the viability of prospective applications.

Zhang, Zhou, and Luo [

28] studied the scheme of applying extracellular vesicles to common gynecologic tumors and discussed their roles in treating tumors. However, while there were a great number of potentialities on both diagnostic and therapeutic capacities for gynecologic oncology, it is still at the exploratory stage when cooperating this means with explainable AI.

Given the test results of gynecologic cancer patients, Maruthi et al. [

29] presented a brief experimental study on identifying the clinical utility rate of their tests and analyzing the survival benefits for those receiving targeted therapy. While the high clinical utility of the tests used by gynecologic oncologists appeared to be a significant survival benefit, limited technical input combined with AI stands for their weakness. Besides, combining AI and genes represents a progressive tendency for future immunotherapy, which is capable of integrating information from multiple parameters, revealing characteristics of tumors, and providing implications for treatment decisions [

3].

Terlizzi et al. [

30] reported tests of applying 3D pulsed dose rate brachytherapy for curing children with vaginal tumors, where their proposed strategy on multimodal organ conservation was expected to achieve better oncological results for some typical cases of pediatric vaginal cancers.

When applying image segmentation and classification algorithms to handle cervical screening images, deep-learning-based solutions were reviewed by Youneszade et al. [

31], which suggests adopting viable AI techniques and supporting female patients with early detection, diagnosis and treatment of cervical cancer.

Liu et al. [

32] studied pre-treatment histopathology images of high-grade ovarian cancers, when predicting sensitivity or resistance of this cancer to subsequent platinum-based chemotherapy. A deep-learning-based Al framework was presented on improving the prediction of responses to therapy of high-grade serous ovarian cancers, as well as any further adaptation to other types of gynecological cancers and imaging modalities.

With respect to potential challenges in emergency medicine, Okada, Ning, and Ong [

33] displayed keynote definitions, importance, and the role of explainable AI, aiming to make those concepts in emergency contexts more clearly understandable by clinicians.

Ghnemat et al. [

34] performed medical image classification using explainable AI and accomplished 90.6% testing and validation accuracy on a relatively small image dataset, demonstrating improved accuracy and reduced time cost may practically fit the medical diagnosis, and thereby suggesting the interpretability and transparency of explainable AI on promoting medical diagnosis, and candidates on transplanting feasible schemes for gynecological oncology.

Allahqoli et al. [

35] performed an updated review of all the relevant studies on the promising applications of 18F-FDG PET/MRI and 18F-FDG PET/CT in five categories of gynecological malignancies, where the results indicate potential capacities and existing challenges of non-invasive imaging tools of those FDG PET/MRI and FDG PET/CT for enhancing the management of gynecological cancers.

Sekaran et al. [

36] developed a creative game theoretic approach, i.e., the Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) on analyzing the results of the vaginal microbiome in cervical cancer by classifying relative species, then showing confirmation with this AI model in the presence of pathogenic microbiomes in vaginal samples of cervical cancer, and their mutuality with microbial imbalance.

Considering patients with uterine cervical cancer undergoing radiation therapy and the related late bladder toxicity, Cheon et al. [

37] derived a lightweight prediction model and compared the performance of logistic regression with deep-learning models when predicting late bladder toxicity in patients with cervical cancer, where the outcome of patients got improved and featured as minimized treatment-related complications with secured reliability.

Abuzinadah et al. [

38] put up a stacked explainable AI model to accelerate screening and offer more accurate results on predicting, detecting, and treating ovarian cancer, which achieved an accuracy of 96.87% among 49 features on enhancing detection results, elaborating viable applications of explainable AI techniques for better understandings.

Most recently, when establishing a comprehensive overview of long-axial field-of-view (LAFOV) PET/CT imaging for those patients with gynecological malignant tumors, Triumbari et al. [

39] explored some potential applications and benefits for all phases of management, i.e., the initial staging to surgery and radiotherapy planning, evaluation of treatment response, restaging, as well as later patient-tailored care.

Another latest review was proposed by Margul, Yu and AlHilli [

40], which studied the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) in all three major types of gynecological tumors and vaginal/vulvar cancers. Data sources of clinical trials were analyzed, proving their understanding of TIME to treat gynecologic malignancies.

Pang, Xiu and Ma [

41] summarized the progress of explainable AI when diagnosing, treating, and predicting mediastinal malignancies with a cross-area survey of machine learning and artificial intelligence, where the potential shortcomings may lie on the shortage of clear definitions of specific type of tumors and lacking visible experimental results. Similar problematic issues were also inherent when specifically interpreting and understanding the machine learning models from explainable AI as proposed by Robert et al. [

42]. Most notably, reviewing applicable AI-based radiomics by Wang et al. [

43] toward similar assessment of ovarian cancers is more specific, claiming its potential to enhance the capacities of diagnosis and prognostic prediction in patients to facilitate the innovative concept of precision medicine.

Seo, Refai and Hile [

44] applied a modern data-driven learning technique for testing spatiotemporal plantar pressure data collected from 16 female patients with active breast, ovarian or uterine cancers by walking through the high-resolution sensor-impregnated walkway, then reported an average accuracy of over 86% in tests. It is concluded that for automatic identification of peripheral neuropathy and other chemotherapy side effects, which might have a great impact on mobility, indicating the presence of persistent deviation from pre-chemotherapy step consistencies of survivors. Meanwhile, Jopek et al. [

45] also developed a multi-class deep-learning-based scheme, which was integrated as similar as the explainable AI approach (XAI) - SHAP, where the outcome was originated from a set of sixty genes to show its promising capacity on cancer detection, and could support the decision-making process of clinicians for complicated case of tumors.

Integrations of AI and applications into a variety of medical specialties for clinical practice were reviewed by Karalis [

46], which justified the enhanced accuracy of AI-aided diagnosis and personalized treatment plans in addition to special reference on legal and ethical concerns. A short subsection discussed obstacles and progress of integrating AI in obstetrics and gynecology while neglecting recent advances in gynecological oncology, which renders a shortcoming in this set of work arousing further discussions.

However, there are quite a few challenging issues for explainable AI. There are rather scarce image datasets in cervical malignant tumors and a shortage of external validation [

47]. Longer periods and higher expenses are common for auxiliary diagnostic systems such as colposcopy, while the necessity of developing dynamic systems for explainable AI imaging and the relative unfamiliarity in a certain domain remain potential technical barriers for conducting research. Secondly, despite some early-stage screening algorithms undergoing extensive training, most are small-scale sample investigations and short of external validation. Besides, take the field of radiotherapy as an example [

18]: Recent studies of AI are mainly oriented on head and neck cancers as well as prostate cancers, while such progress was mostly restricted to gynecology. Besides, in chemotherapy and immunotherapy, the compatibilities of explainable AI with equipment, reagents, images, and dependencies on a large number of high-quality datasets and deep-learning-based methods still represent prevalently tricky issues. Needless to say, the interpretability of diagnostic results and ethical responsibilities for the doctor-patient relationships and topics on intelligent health management [

3]. Most notably, applications of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) for psychological therapy and remote medicine come across restrictions of time and space, also benefit the treatment of gynecological cancers to ensure the optimal opportunities of medical care and thereby release the unbalanced distribution of medical resources, which are under development towards higher-level system integration, offering advanced support for gynecological oncology [

48].

4. Discussion

In retrospect to those technical advances of explainable AI, a variety of considerable achievements were fulfilled on early screening and precise diagnosis of gynecological tumors, especially in the field of AI-aided diagnostic imaging and pathological analysis. However, it is still difficult to select the most appropriate AI techniques for accuracy, reliability, and efficacy. In addition, regarding the applications of new staging, which jointly adopt pathological classifications and molecular classifications, a booming demand for human labor may appear for pathologists, where explainable AI provides solutions for sharing some of their workload due to the presence of big data, advanced neural networks, weakly supervised learning schemes as well as deep-learning based algorithms.

Up till now, a brief study on the connective communications of explainable AI and clinical advances in gynecological oncology is presented, where the major contributions of our work are summarized as follows:

i) Firstly, we picked up some keynote AI-based approaches on the very specific topics of gynecological oncology, including theoretical advances in the past decade, early-stage screening, and diagnostic and surgical treatments with respect to several practical fields, with some emphasis on a couple of present mature systems for radiotherapy treatments.

ii) Secondly, we established a narrow but complete investigation on applicable areas of explainable AI in several crucial branches of diagnosing and treating gynecological malignant tumors, i.e., disease warning, pathological analysis, virtual reality, minimally invasive surgical planning and health management, etc. Enhanced detection accuracy, time efficiency, and quality evaluation of those technical advances have been refreshed and are up to date.

iii) Last but not least, coping with the concept of integrating AI and biomedical science towards future healthcare, the potential weakness of prior studies in a small portion of the listed research products are specified along with potential challenging issues in the field of study on gynecological oncology and practical devices for clinical use.

Despite such kind of innovative ideas and critical thinking in those aforementioned manifolds, our study still has several limitations, which are concisely described below:

To begin with, explainable AI techniques are progressing in the primary stage, where the specific values of clinical applications and marketing potentials are beyond discussion. Restrictions such as lacking self-awareness, emotional response and perspective reflecting on individual situations, remain open to problems candidating for solution [

3]. Besides, many current explainable AI schemes involve complicated high-performance computer-aided techniques, which might not be friendly to most common clinicians. In other words, explainable AI is effective only if it truly saves time and improves efficiency for most people, and this concept is also universally applicable to any clinical branch related to gynecological oncology. Meanwhile, due to the scarcity of either first-hand clinical data or practical implementation of algorithms, we still do not have a uniform platform to train, test, and validate those technical advances, i.e., deep learning-based schemes for the latest study on gynecological tumors, hence, our set of work demands prospective orientations and progressive exploration in machine learning and deep learning-based framework for medical image analysis [

49,

50], self-distillation framework of multiple-instance learning for image classification [

51], deep transfer learning with explainable AI paradigm when diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease [

52], and other reliable applications of explainable AI for gynecological oncology towards the promising goal of precision medicine in digital health [

18,

53].

The accepted fifty-five papers in this communication article originated from research scholars among twenty-nine nations: Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, China, Egypt, France, Germany, Greece, India, Iran, Italy, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, Netherlands, Nigeria, Pakistan, Poland, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Qatar, UK, and USA.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

In sum, the latest progress of explainable AI in the field of gynecological oncology is mainly distributed on cytological screening of cervical lesions, disease warning and early diagnosis of uterine and ovarian tumors, etc. While introducing refreshed statistical explanations and by means of diagnostic imaging and pathological analysis, subsidiary treatment plans are provided for clinicians. More specifically, virtual reality, minimally invasive technology, and intelligent robots may provide new concepts and challenges for difficulties of pre- and intra-operative strategies, and speed up post-operative healing for gynecological tumors. In the practical fields such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy, etc., deeper involvements of AI technology integrate multi-parameter information, accelerate the revelation of crucial features on tumors, supplement clinical decision-making, and optimize treatment plans, which stand for a much more popular trend for the future developments of gynecological oncology.

We sketch plans for prospective study on explainable AI with gynecological cancers in the following manifolds: for the purpose of multi-center and larger-scale investigations, public image group data platform demands installation for expanding image datasets and covering various radiotherapy centers, which is within our scope for dataset construction. Meanwhile, explainable AI-based techniques not only call for clinical translation, but also require accuracy enhancement in radiotherapy applications, where those perspectives are originated from data sources, quality control, technical support and reliable algorithms themselves [

54]. In addition to Chat-GPT and beyond techniques [

55] on AI for healthcare, we also intend to seek for in-depth cooperations with clinical departments in provincial hospitals and research institutions for the information sharing of related issues and facing up with those challenging topics of gynecological oncology in the new era of “Healthy China 2030”. Finally, thanks to the progressive discovery of applicable values in these explainable AI-based models, future exploration, and deeper integration with their viability, interpretability, accuracy, and reliability, our society may benefit from refreshed ideas and improved solutions for the diagnosis and treatment of gynecological tumors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.G. and Y.-D. Z.; methodology, X.G.; validation, X.G., and Y.-D. Z.; formal analysis, X.G., H.-H. L.; investigation, X.G. and C.-X. Y.; resources, X.G., Q.-X. S, Z.-L.Y., S.-C. S.; data curation, X.G., H.-H. L. and L.-L. Z; writing—original draft preparation, X.G.; writing—review and editing, X.G., H.-H. L. and Y.-D. Z; supervision, C.-X.Y. and Y.-D. Z.; project administration, X.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors received no external research funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Duan, R.-F.; Zhang, H.-P.; Yu, J.; Deng, S.-S.; Yang, H.-J.; Zheng, Y.-T.; Huang, Y.-C.; Zhao, F.-H. , Yang, H.-Y. Temporal trends and projections of gynecological cancers in China, 2007-2030. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, W.-Y.; Hosny, A.; Schabath, M.B.; Giger, M.L.; Birkbak, N.J.; Mehrtash, A.; Allison, T.; Arnaout, O.; Abbosh, C.; Dunn, I.F.; Mak, R.H.; Tamimi, R.M.; Tempany, C.M.; Swanton, C.; Hoffmann, U.; Schwartz, L.H.; Gillies, R.J.; Huang, R.Y.; Aerts, H.J. W. L. Artificial intelligence in cancer imaging: clinical challenges and applications. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 0, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.-L; Li, L. Research and applications of big data and artificial intelligence on gynecological malignant tumors. Chin. J. Prac. Gynecol. Obstet. 2019, 35, 720–723. [Google Scholar]

- Kyrgiou, M.; Pouliakis, A.; Panayiotides, J.G. Personalised management of women with cervical abnormalities using a clinical decision support scoring system. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 141, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pergialiotis, V.; Pouliakis, A.; Parthenis, C.; Damaskou, V.; Chrelias, C.; Papantoniou, N.; Panayiotides, I. The utility of artificial neural networks and classification and regression trees for the prediction of endometrial cancer in postmenopausal women. Public Health 2018, 164, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bora, K.; Chowdhury, M.; Mahanta, L.B.; Kundu, M.K.; Das, A.K. Automated classification of Pap smear images to detect cervical dysplasia. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 2017, 138, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, T.A.; Puppala, M.; Ogunti, R.O. ,Ensor, J.E.; He, T.-C.; Shewale, J.B.; Ankerst, D.P.; Kaklamani, V.G.; Rodriguez, A.A.; Wong, S.T. C.; Chang, J.C. Correlating mammographic and pathologic findings in clinical decision support using natural language processing and data mining methods. Cancers 2017, 123, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, M.; Horie, K.; Hara, A.; Miyamoto, Y.; Kurihara, K.; Tomio, K.; Yokota, H. Application of deep learning to the classification of images from colposcopy. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 3518–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aramendia-Vidaurreta, V.; Cabeza, R.; Villanueva, A.; Navallas, J.; Alcázar, J.L. Ultrasound image discrimination between benign and malignant adnexal masses based on a neural network approach. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2016, 42, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.H.; Mousavi, H.S.; Monga, V.; Rao, G.; Rao, UK A. Histopathological image classification using discriminative feature-oriented dictionary learning. IEEE Trans. Med. Imag. 2016, 35, 738–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Le, L.; Nogues, I.; Summers, R.M.; Liu, S.-X.; Yao, J.-H. DeepPap: deep convolutional networks for cervical cell classification. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2017, 21, 1633–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sornapudi, S.; Stanley, R.J.; Stoecker, W.V.; Almubarak, H.; Long, R.; Antani, S.; Thoma, G.; Zuna, R.; Shelliane, R.; Frazier, S.R. Deep learning nuclei detection in digitized histology images by superpixels. J. Pathol. Inform. 2018, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinno, A.K.; Fader, A.N. Robotic-assisted surgery in gynecologic oncology. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 102, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aruni, G.; Amit, G.; Dasgupta, P. New surgical robots on the horizon and the potential role of artificial intelligence. Investig. Clin. Urol. 2018, 59, 221–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussa, H.G.; Husseini, G.A.; Abel-Jabbar, N.; Ahmed, S. Use of model predictive control and artificial neural networks to optimize the ultrasonic release of a model drug from liposomes. IEEE Trans. Nanobiosci. 2017, 16, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Tian, Y.-H.; Song, C.; Wang, J.; Zou, Y.-G.; Anderson, G.A.; Han, J.-Y.; Chang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, L.; Zhou, G.-B.; Nie, G.-J. , Yan, H.; Ding, B.-Q.; Zhao, Y.-L. A DNA nanorobot functions as a cancer therapeutic in response to a molecular trigger in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsi, M.; Sedaghatkish, A.; Dejam, M.; Saghafianc, M.; Mehdi Mohammadi, M.; Sanati-Nezhad, A. Magnetically assisted intraperitoneal drug delivery for cancer chemotherapy. Drug Deliv. 2018, 25, 846–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, M.; Liu, X.-X.; Xu, C.-J.; Zhang, X.-Y. Research progress on application of artificial intelligence (AI) in radiotherapy for gynecological malignancy. China J. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 31, 671–674. [Google Scholar]

- Nwankwo, O.; Mekdash, H.; Sihono, D.S.K.; Wenz, F.; Glutting, G. Knowledge-based radiation therapy (KBRT) treatment planning versus planning by experts: validation of a KBRT algorithm for prostate cancer treatment planning. Radiat. Oncol. 2015, 10, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Hosny, A.; Parmar, C.; Quackenbush, J.; Schwartz, L. H; Aerts, H. Artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, C.B.; Li, S.; Battin, F.; McKeague, J.; Peters, C.A. External beam planning module of Eclipse for external beam radiation therapy. Med. Dosim. 2018, 43, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Zeng, Z.-Y.; Li, L. Progress of artificial intelligence in gynecological malignant tumors. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 12823–12840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, K. ; Ikeda, M; Hayashi, M.; Matsuo, K.; Yasaka, M.; Machida, H.; Shida, M.; Katahira, T.; Imanishi, T.; Hirasawa, T.; Sato, K.; Yoshida, H.; Mikami, M. Comprehensive serum glycopeptide spectra analysis combined with artificial intelligence (CSGSA- AI) to diagnose early-stage ovarian cancer. Cancers, 2020; 12, 2373. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.-D.; Gorris, J.M.; Wang, S.-H. Deep learning in medical image analysis: a review. J. Imag. 2021, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.-Y.; Wang, Q.-B.; Ma, Y.-T. Cervical optical coherence tomography image classification based on contrastive self-supervised texture learning. Med. Phys. 2022, 49, 3638–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, F.G.; Pavlik, E.J. Perspectives on ovarian cancer: 1809 to 2022 and beyond. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmer-Stelmach, A.; Zak, J.; Pawlosek, A.; Rosner-Tenerowicz, A.; Budny-Winska, J.; Pomorski, M.; Fuchs, T.; Zimmer, M. The application of artificial intelligence-assisted colposcopy in a tertiary care hospital within a cervical pathology diagnostic unit. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Zou, Y.; Luo, J. Application of extracellular vesicles in gynecologic cancer treatment. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruthi, V.K.; Khazaeli, M.; Jeyachandran, D.; Desouki, M.M. The clinical utility and impact of next generation sequencing in gynecologic cancers. Cancers 2022, 14, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlizzi, M.; Minard, V.; Haie-Meder, C.; Espenel, S.; Martelli, H.; Guérin, F.; Chargari, C. Implementation of image-guided brachytherapy for pediatric vaginal cancers feasibility and early clinical results. Cancers 2022, 14, 3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youneszade, N.; Marjani, M.; Chong, P.-P. Deep learning in cervical cancer diagnosis: architecture, opportunities, and open research challenges. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 6133–6149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lawson, B.C.; Huang, X.; Broom, B.M.; Weinstein, J.N. Prediction of ovarian cancer response to therapy based on deep learning analysis of histopathology images. Cancers 2023, 15, 4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y.; Ning, Y.-L.; Ong, M.E.H. Explainable AI in emergency medicine: an overview. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2023, 10, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghnemat, R.; Alodibat, S.; Abu Al-Haija, Q. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) for deep learning based medical image classification. J. Imaging 2023, 9, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahqoli, L.; Hakimi, S.; Laganà, A.S.; Momenimovahed, Z.; Mazidimoradi, A.; Rahmani, A.; Fallahi, A.; Salehiniya, H.; Ghiasvand, M.M.; Alkatout, I. 18F-FDG PETMRI and 18F-FDG PETCT for the management of gynecological malignancies: a comprehensive review of the literature. J. Imaging 2023, 9, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, K.; Varghese, R.P.; Gopikrishnan, M.; Alsamman, A.M.; El Allali, A.; Zayed, H.; Doss C, G.P. Unraveling the dysbiosis of vaginal microbiome to understand cervical cancer disease etiology: an explainable AI approach. Genes 2023, 14, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheon,W. ; Han, M.; Jeong, S.; Oh, E.S.; Lee, S.U.; Lee, S.B.; Shin, D.; Lim, Y.K.; Jeong, J.H.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.K. Feature learning analysis of a deep learning model on predicting late bladder toxicity occurrence in uterine cervical cancer patients. Cancers 2023, 15, 3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzinadah, N.; Kumar Posa, S.; Alarfaj, A.A.; Alabdulqader, E.A.; Umer, M.; Kim, T.-H.; Alsubai, S.; Ashraf, I. Improved prediction of ovarian cancer using ensemble classifier and shapy explainable AI. Cancers 2023, 15, 5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triumbari, E.K.A.; Rufini, V.; Mingels, C.; Rominger, A.; Alavi, A.; Fanfani, F.; Badawi, R.D.; Nardo, L. Long axial field-of-view PETCT could answer unmet needs in gynecological cancers. Cancers 2023, 15, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margul, D.; Yu, C.; AlHilli, M.M. Tumor immune microenvironment in gynecologic cancers. Cancers 2023, 15, 3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.; Xiu, W.; Ma, X. Application of artificial intelligence in the diagnosis, treatment, and prognostic evaluation of media- stinal malignant tumors. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, A.; Potter, K.; Frank, L. Explainable AI: interpreting and understanding machine learning models. Artificial Intelligence, 2024, 1–18; [Online Available]: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/377844899. 3778. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.-L.; Lin, W.-H.; Zhuang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-L. , He, Y.-F.; Li, L.-H.; Lyu, G.-R. Advances in artificial intelligence for the diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cancer. Onco. Rep. 2024, 51, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, K.; Refai, H.H.; Hile, E.S. Application of dynamic mode decomposition to characterize temporal evolution of plantar pressures from walkway sensor data in women with cancer. Sensors 2024, 24, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jopek, M.A.; Pastuszak, K.; Cygert, S.; Best, M.G.; THOMAS WÜrdinger, T.; Jassem, J.; Żaczek, A.J.; Supernat, A. Deep learning-based multiclass approach to cancer classification on liquid biopsy data. IEEE J. Translation. Health Med. 2024, 12, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karalis, V.D. The integration of artificial intelligence into clinical practice. Appl. Biosci. 2024, 3, 14–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.-Y.; Remela, R.; Qiao, Y.-L. Progress and challenge of artificial intelligence in diagnosis treatment of cervical lesions. Chin. Gen. Pract. 2022, 25, 2215–2222, 2230. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.-G; Zhou, G.-W. Artificial Intelligence and Medical Health: Introduction to Application Status and Future Development. Beijing: Publishing House of Electronics Industry, 2021; 181–182. [Google Scholar]

- Moltó-Balado, P.; Reverté-Villarroya, S.; Alonso-Barberán, V.; Monclús-Arasa, C.; Balado-Albiol, M.T.; Clua-Queralt, J.; Clua-Espuny, J.-L. Machine learning approaches to predict major adverse cardiovascular events in atrial fibrillation. Technologies 2024, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litjens, G.; Kooi, T.; Bejnordi, B.E.; Setio, A.A. A.; Ciompi, F.; Ghafoorian, M.; Laak, J.A.W.M. van der; Ginneken, B. van; S’anchez, C.I. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2017, 42, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.-Y.; Qu, L.-H.; Guo, Q.-H.; Song, Z.-J.; Wang, M.-N. Negative instance guided self-distillation framework for whole side image analysis. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 28, 964–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, T.; Barua, K.; Habiba, S.U.; Sharmen, N.; Hossain, M.S.; Andersson, K. An explainable AI paradigm for Alzheimer’s diagnosis using deep transfer learning. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, B. The promise of explainable AI in digital health for precision medicine: a systematic review. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H; Madanchian, M. AI advancements: comparison of innovative techniques. AI 2024, 5, 38–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hulsen, T. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: ChatGPT and beyond. AI 2024, 5, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).