Submitted:

03 August 2024

Posted:

05 August 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Premises on Environmental Sustainability

1.2. Building with Earth

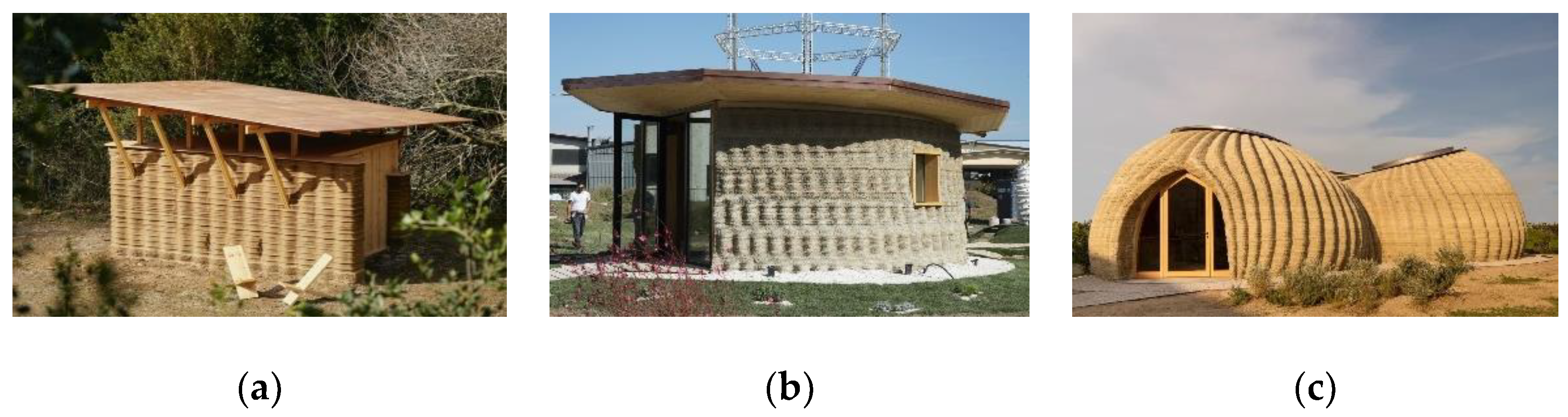

1.3. 3D Printing with Earth: The Challenge of Roofing

2. Materials and Methods

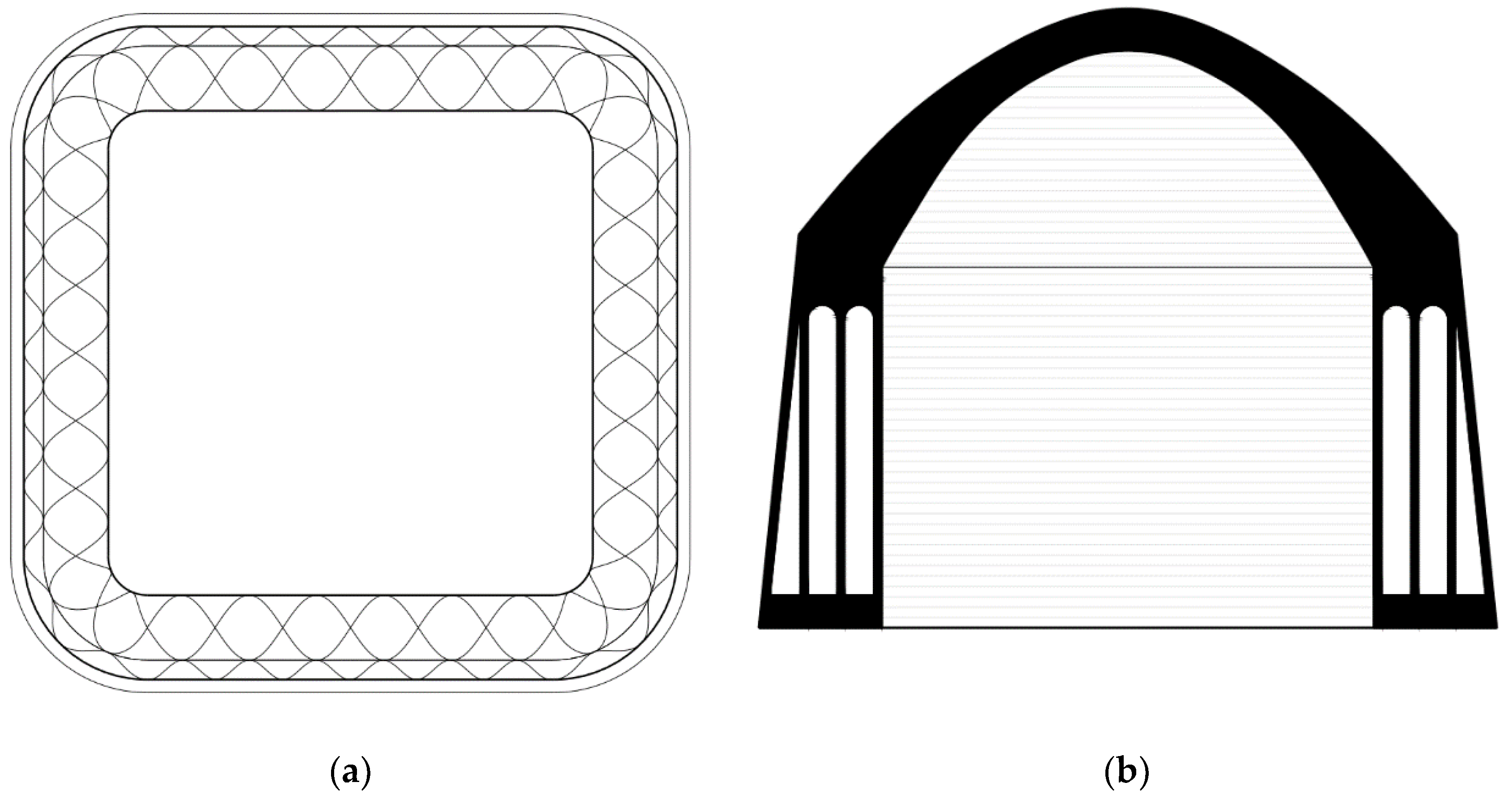

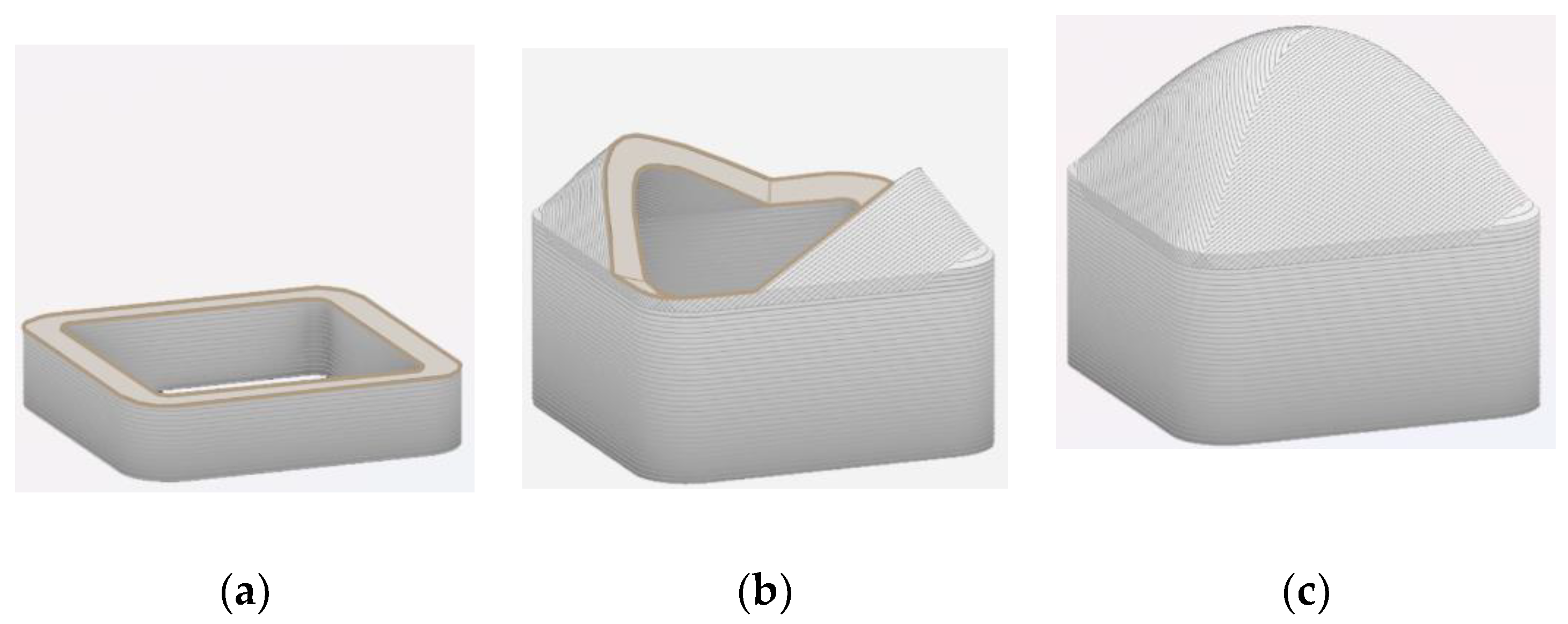

2.1. Definition of the Project Concept

2.2. Structural Design

2.2.1. The Mechanical Properties of the Printed Material

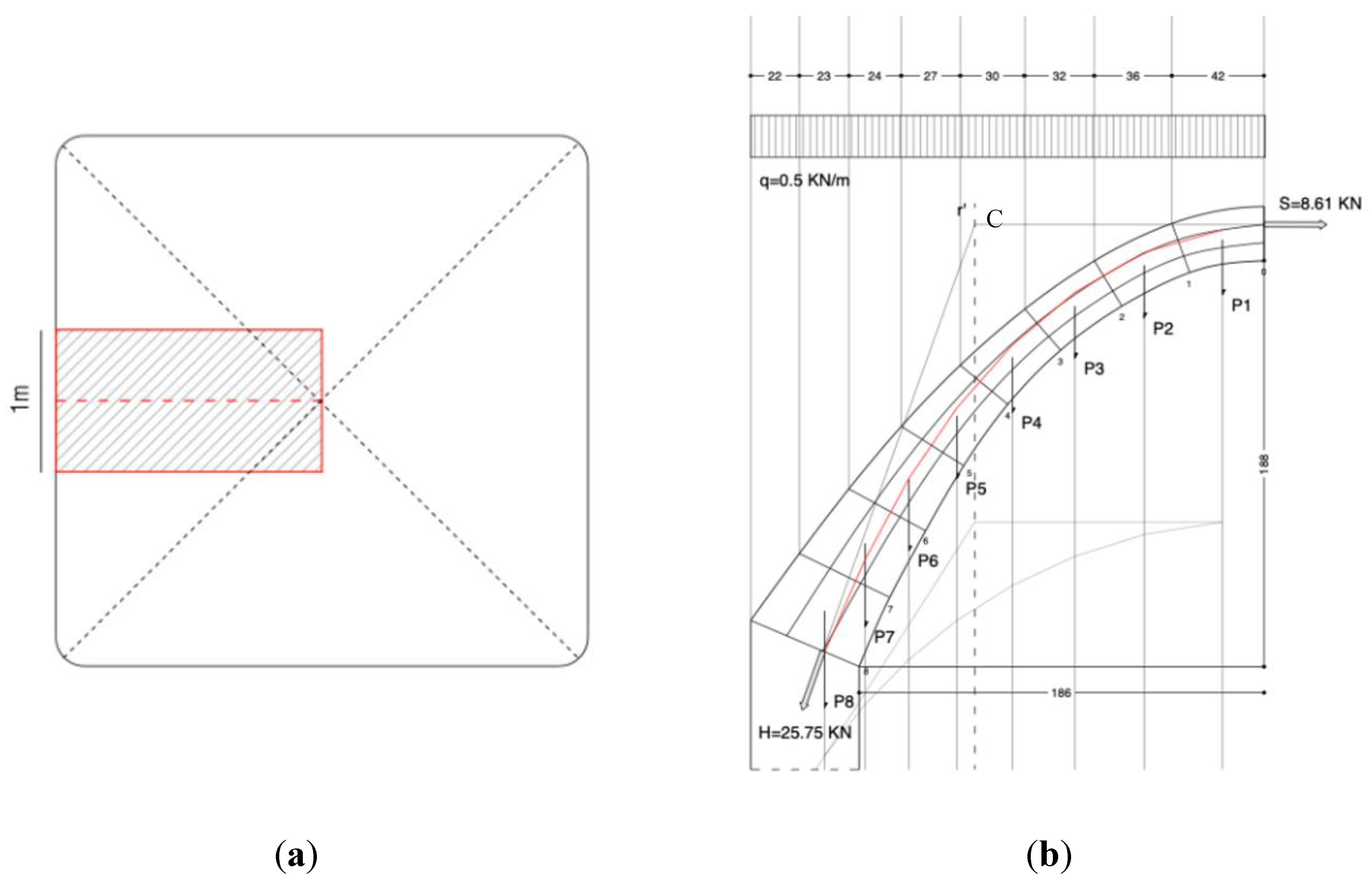

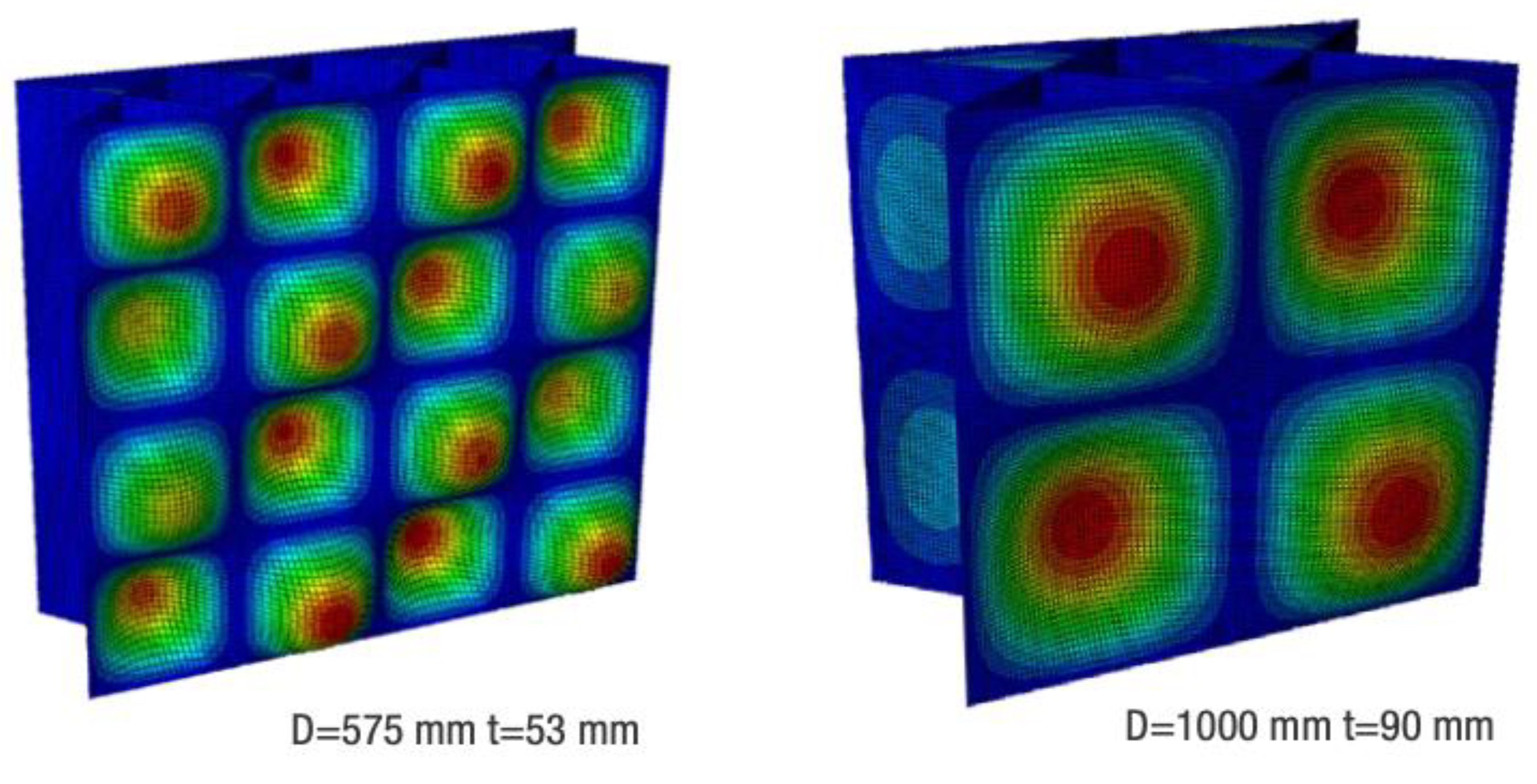

2.2.2. Roof

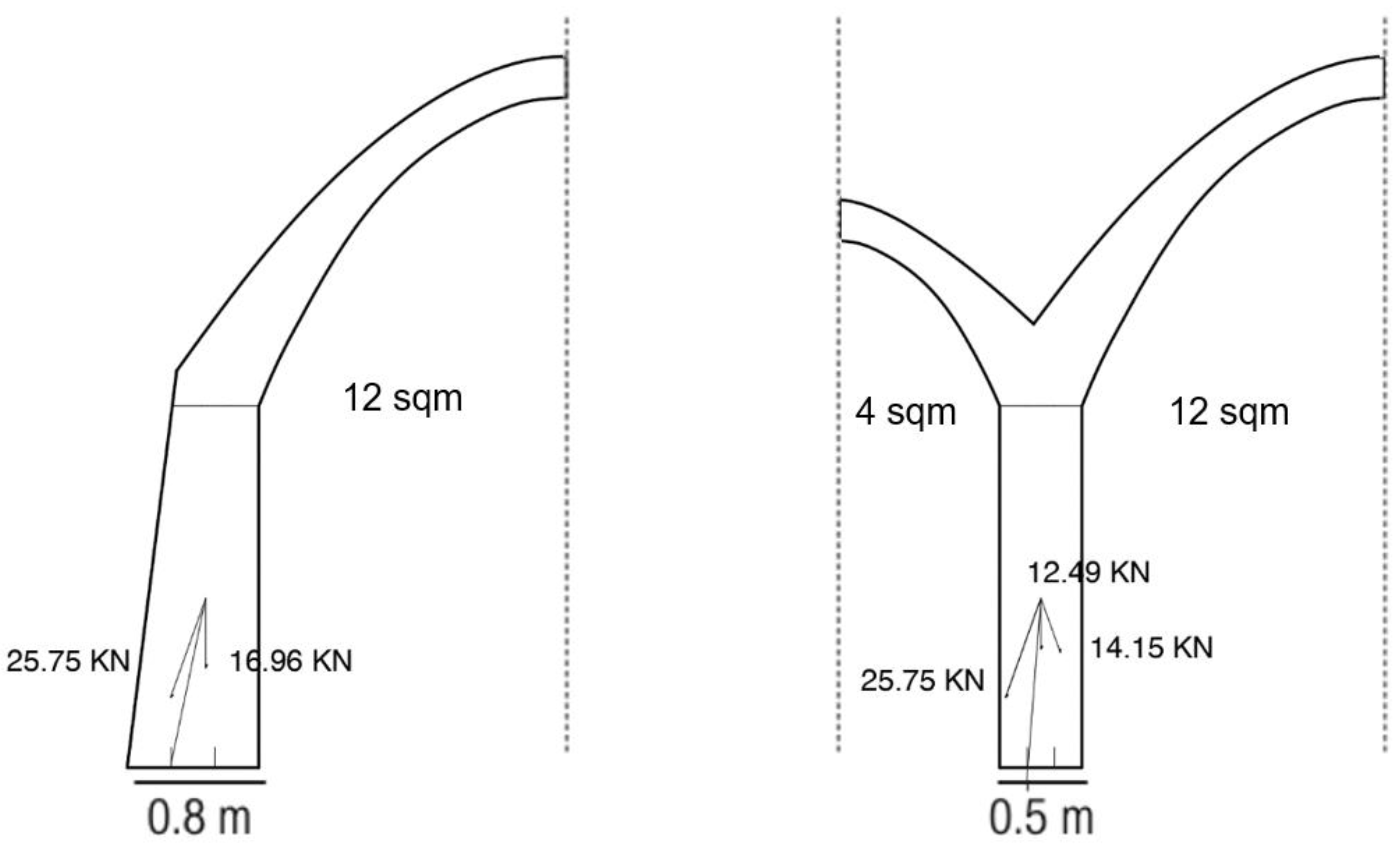

2.2.2.1. 12 sqm Block

- γ= Safety factor;

- b= Length of the block

- s= Height of the block

| Pressure curve | Bending under compression (Keystone) [MPa] |

Bending under compression (Impost) [MPa] |

Shear (Impost) [MPa] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contained in the middle third | 0.057<0.31 | 0.076<0.31 | 0.002<0.13 |

| Pressure curve | Bending under compression (Keystone) [MPa] |

Bending under compression (Impost) [MPa] |

Shear (Impost) [MPa] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contained in the middle third | 0.038<0.31 | 0.052<0.31 | 0.002<0.13 |

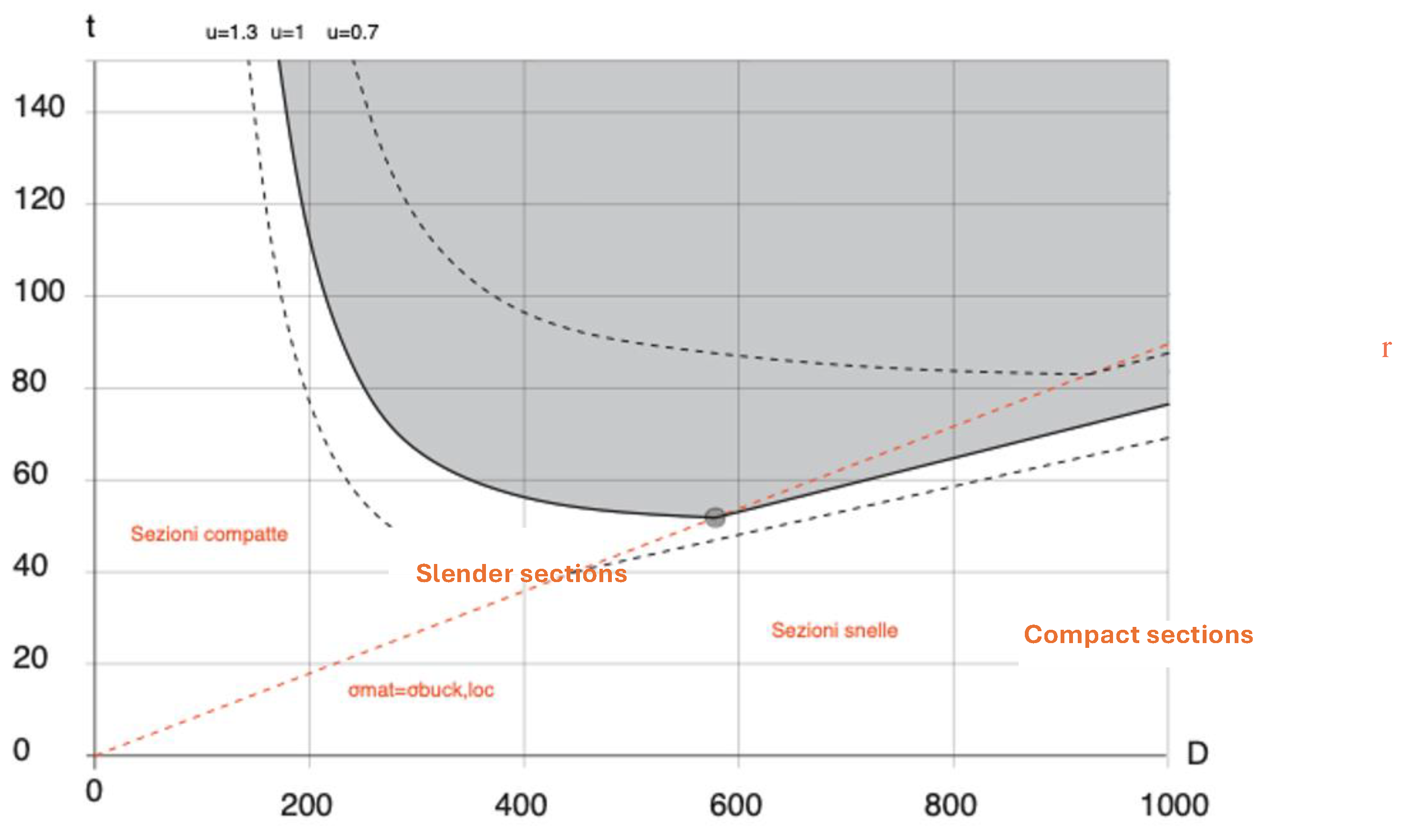

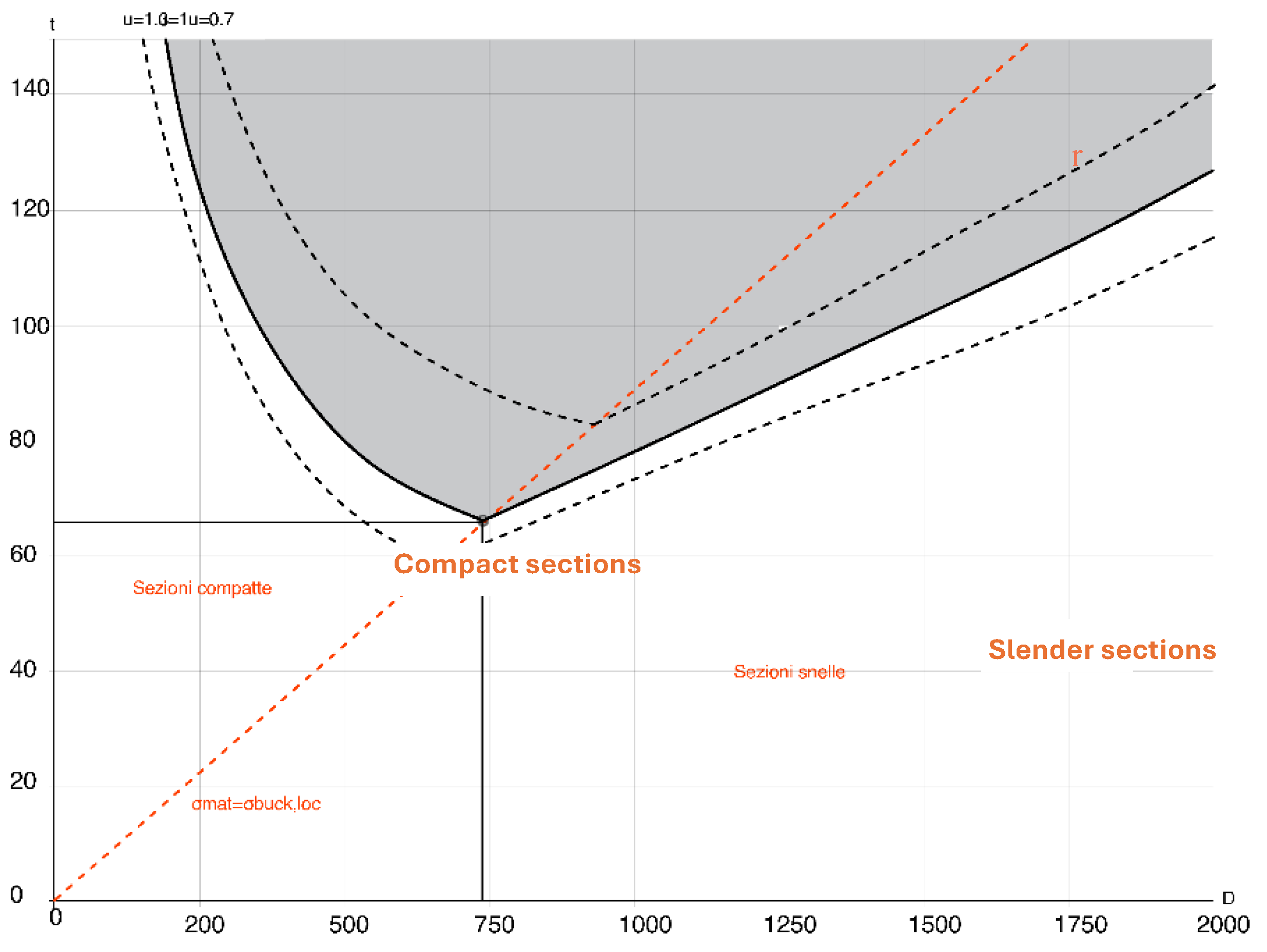

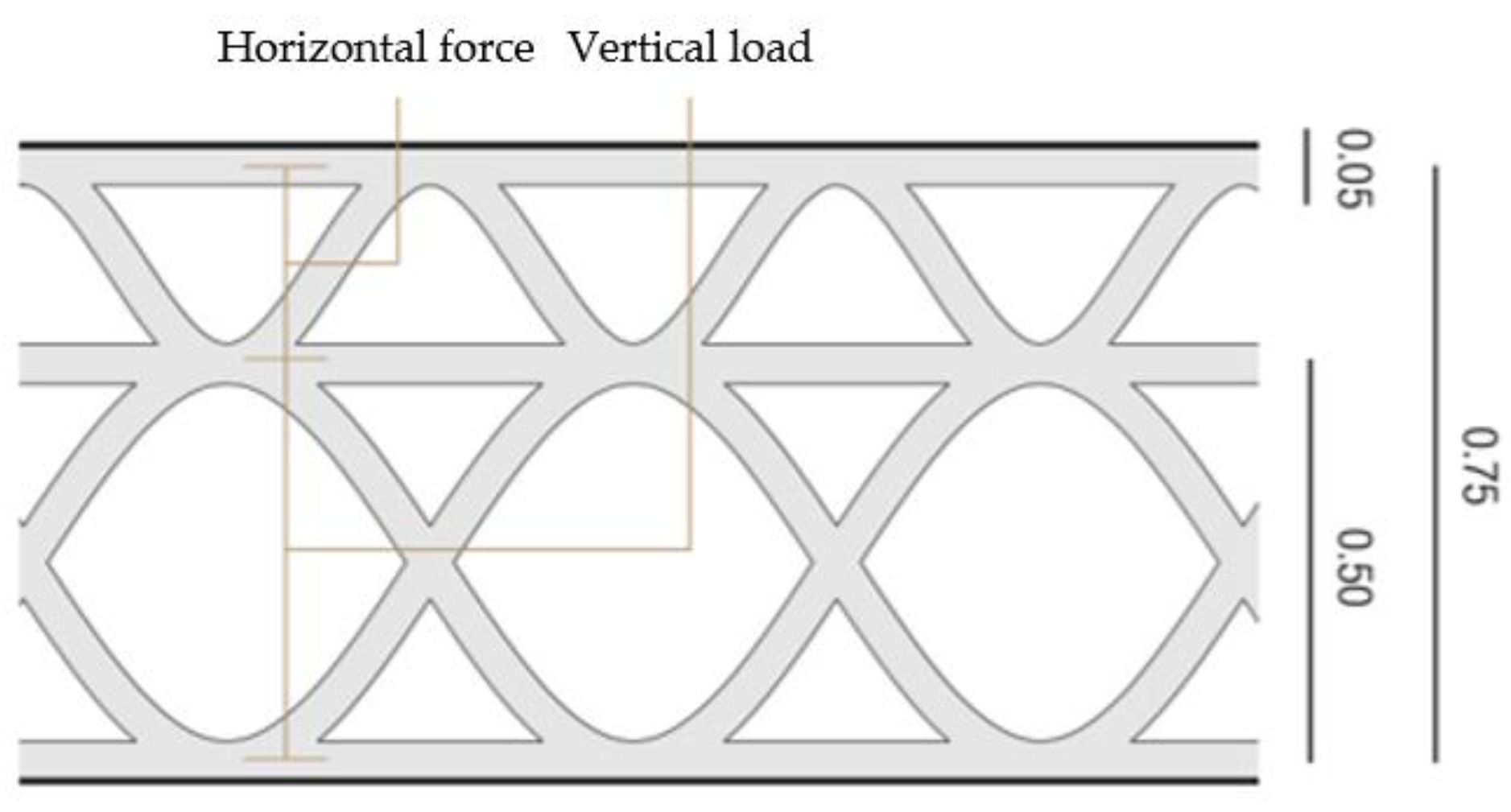

2.2.3. Wall

- Pd= Design resistance;

- P= Maximum compression load;

- γ= Safety factor taken as 2.

- Roof weight Pr= 25.70 KN;

- Wall weight Pw= 1.3 · 18 · 10−9 · (A · 2000 + D ·L · 200)

- Total weight Ptot= Pw+2 · Pr.

- Distance between the mid-axis of the wall and the outermost tensioned fiber c = ;

- Maximum load for global instability ;

- Total eccentricity of vertical loads e = ;

- Eccentricity of the wall’s own weight em = 0.05D ;

- Eccentricity of the wall weight em = 0.05D;

- Eccentricity of the roof weight ec = 0.16D;

- M= S · Lm

3. Results

3.1. Structural Design Results

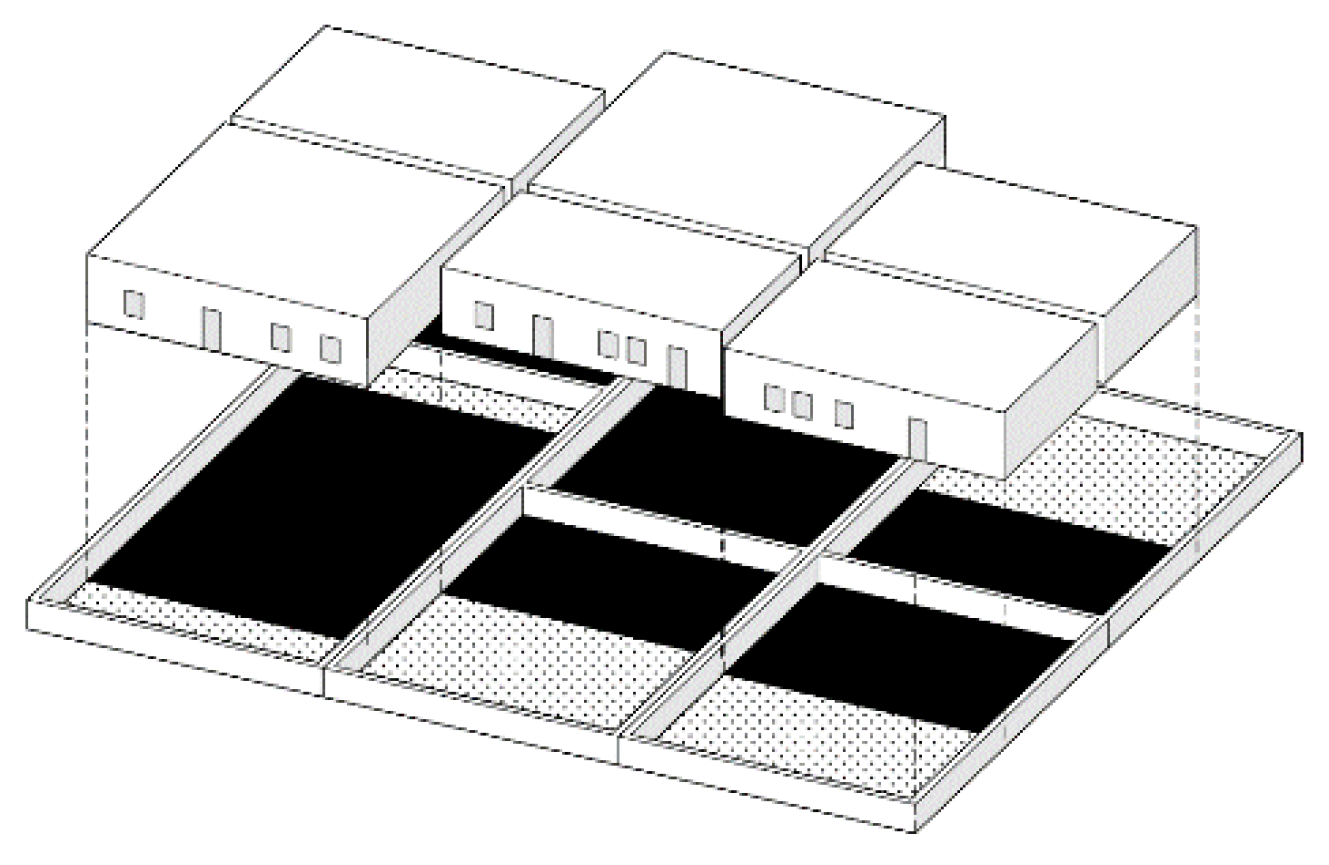

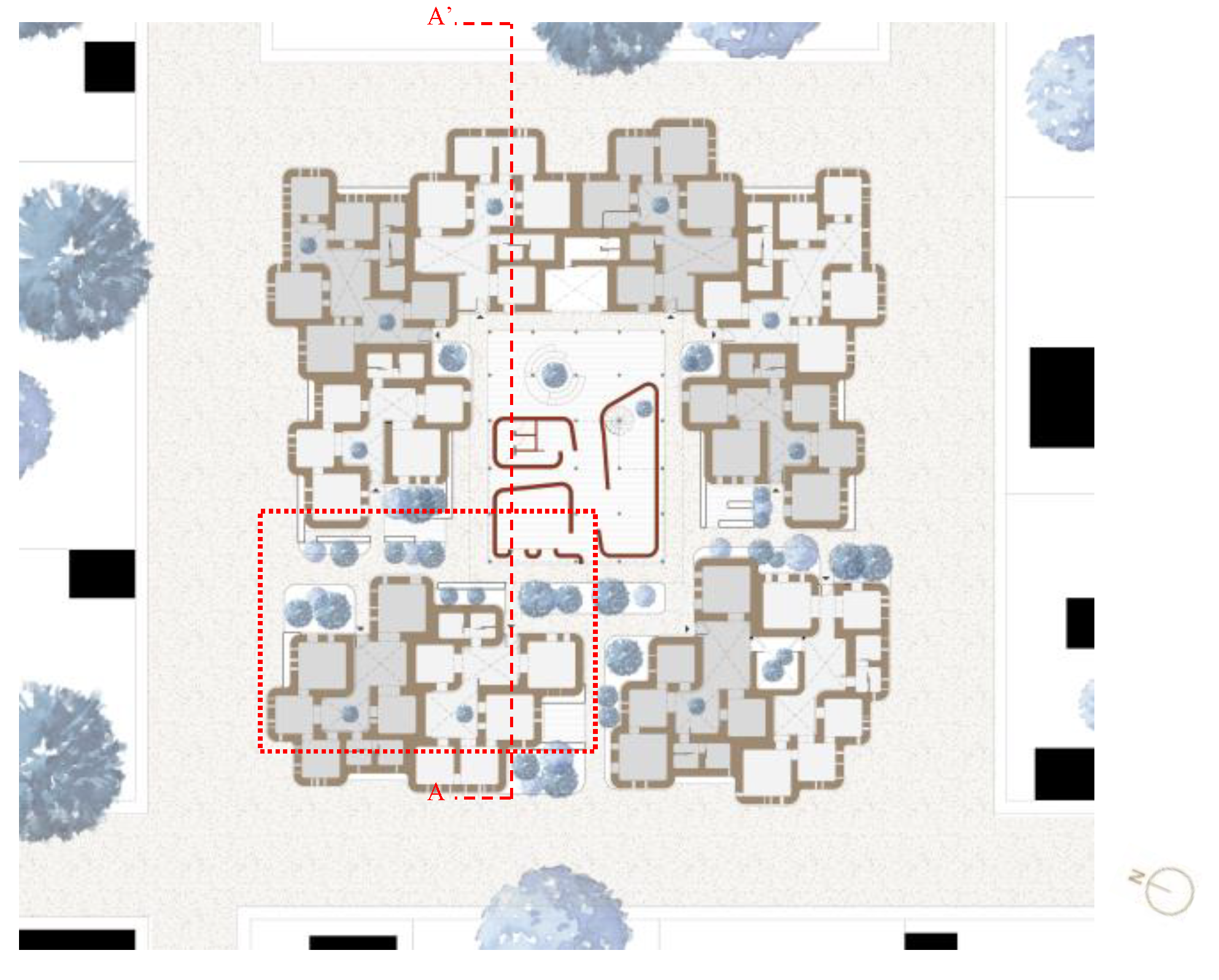

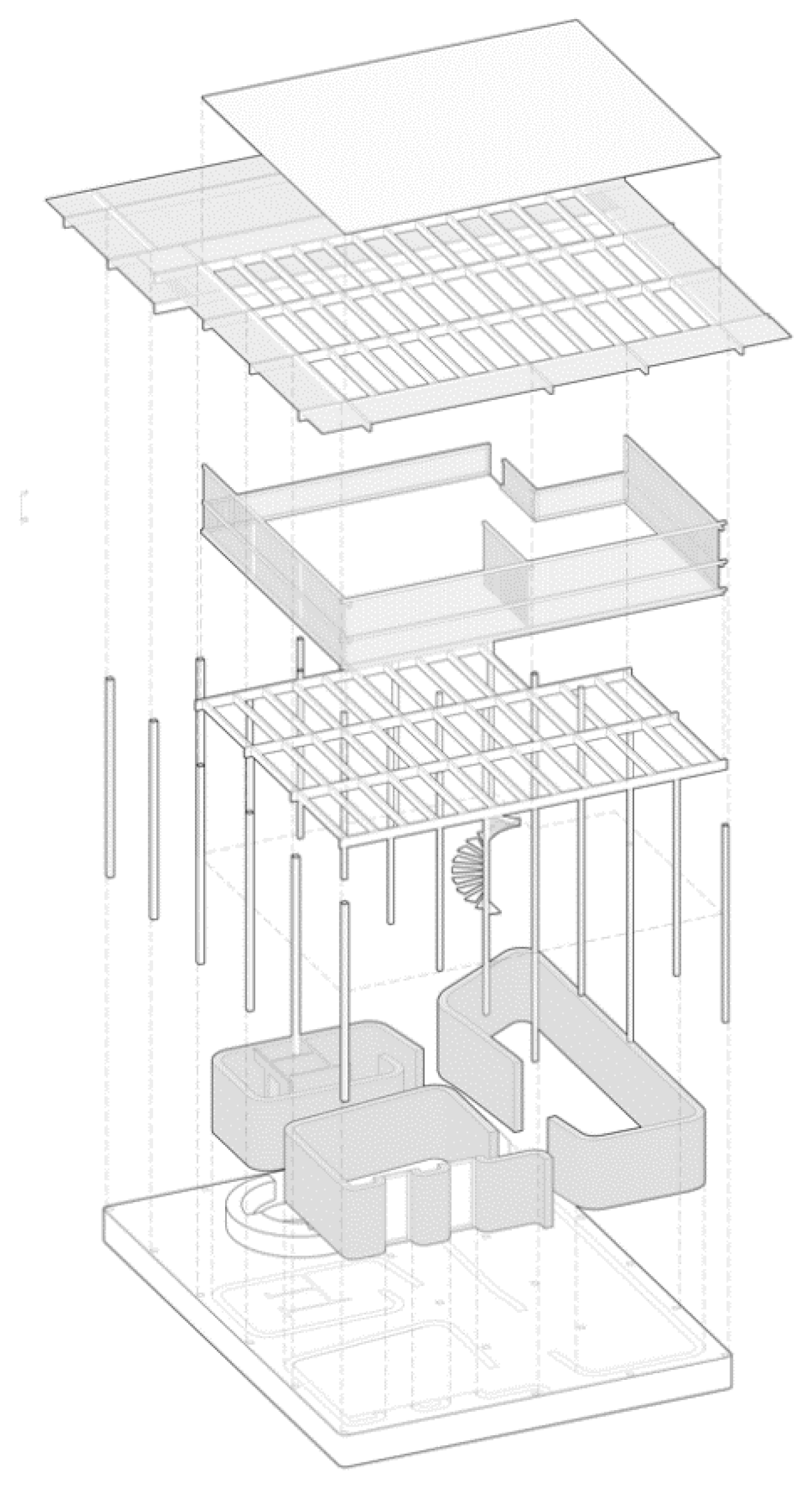

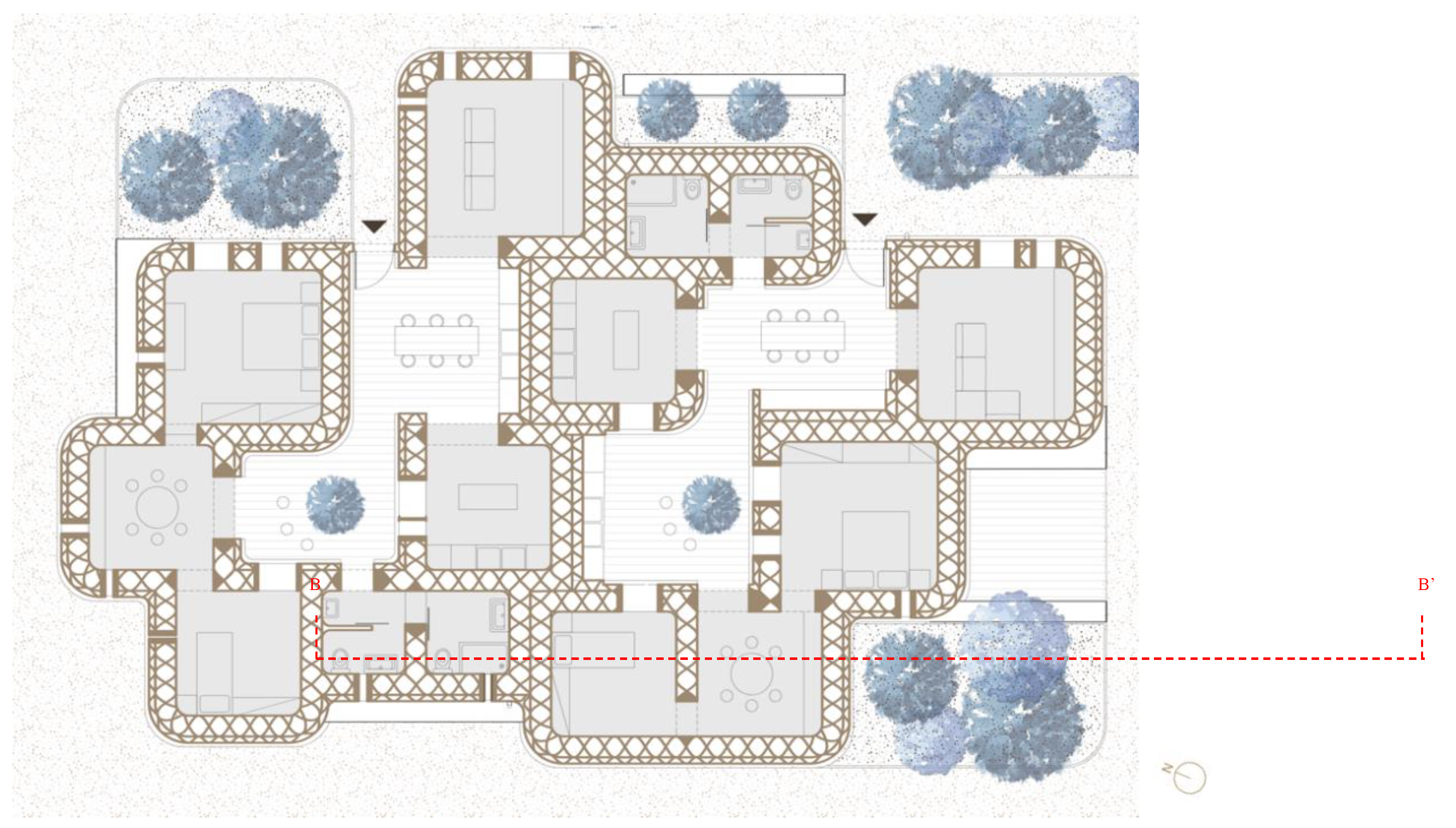

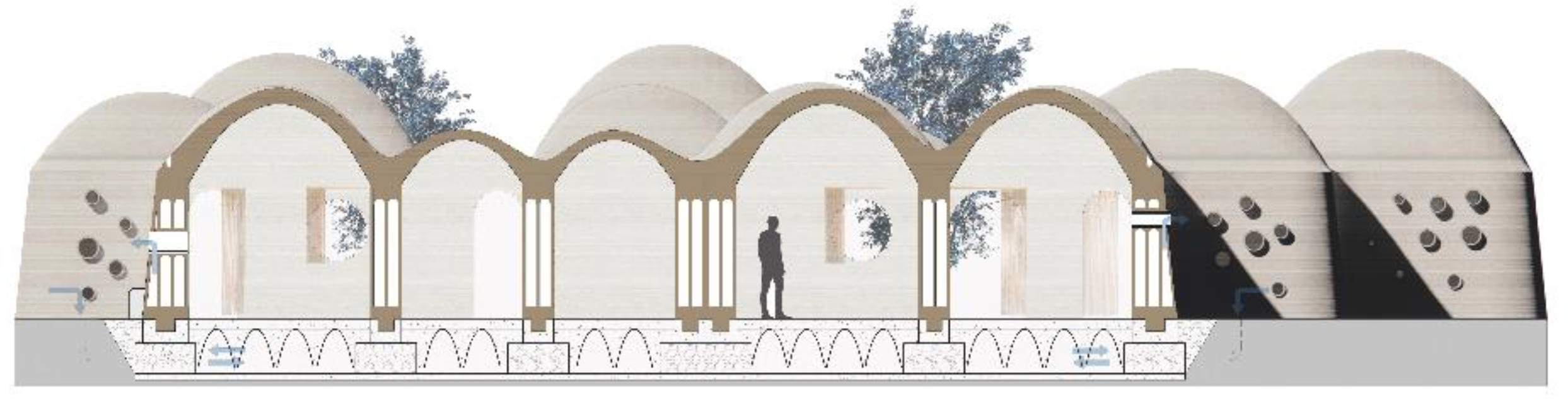

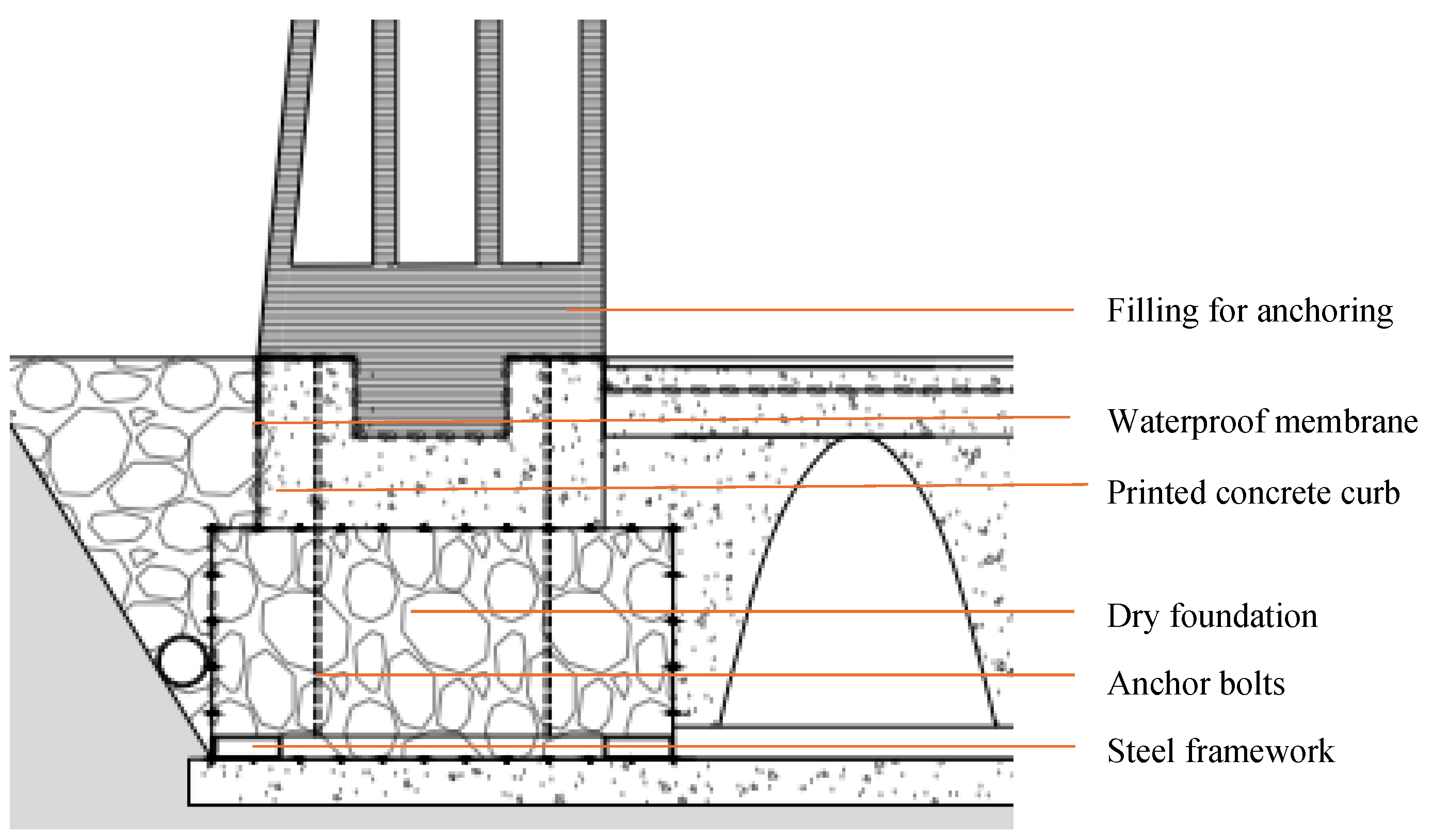

3.2. The Architectural Project

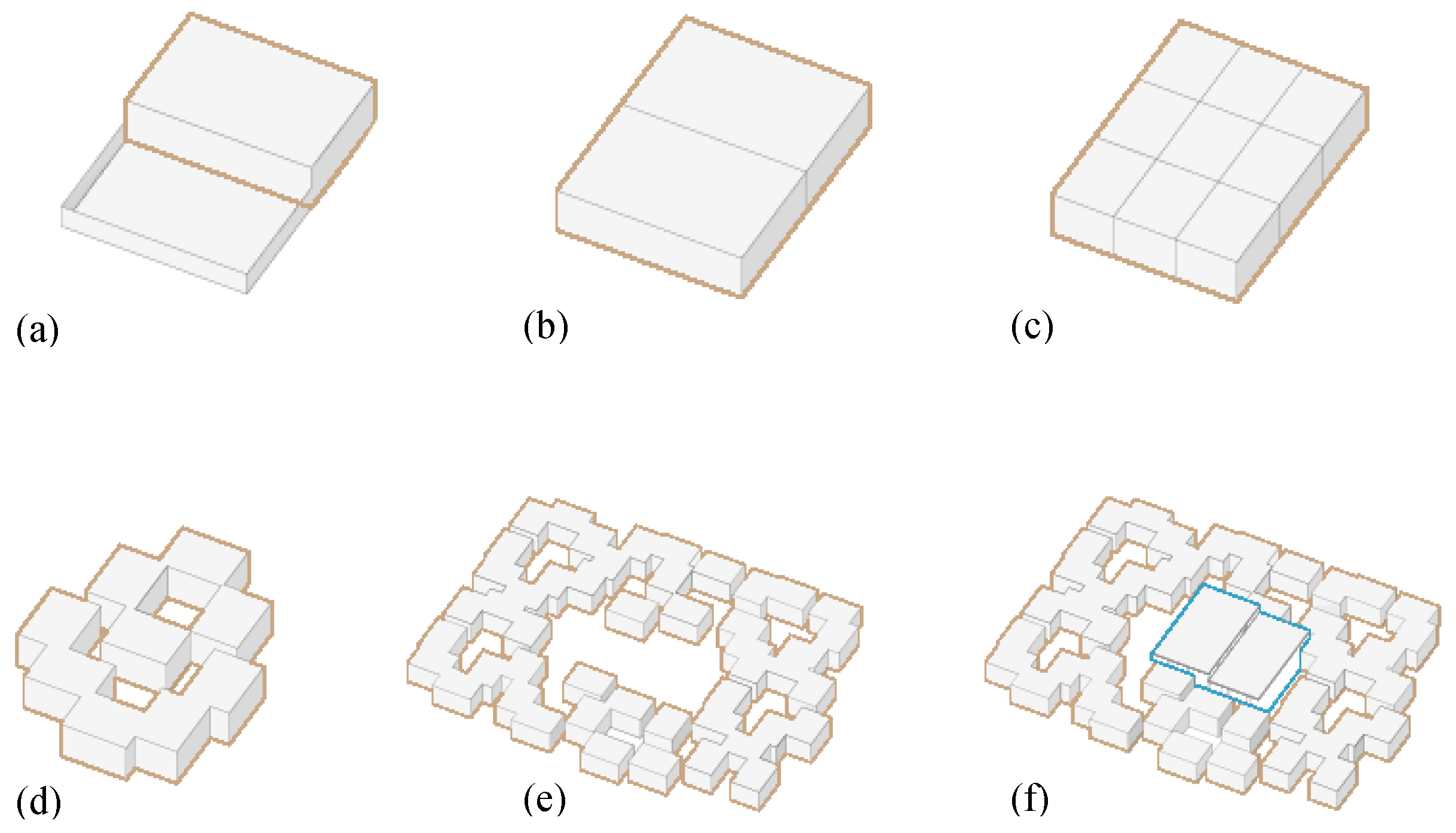

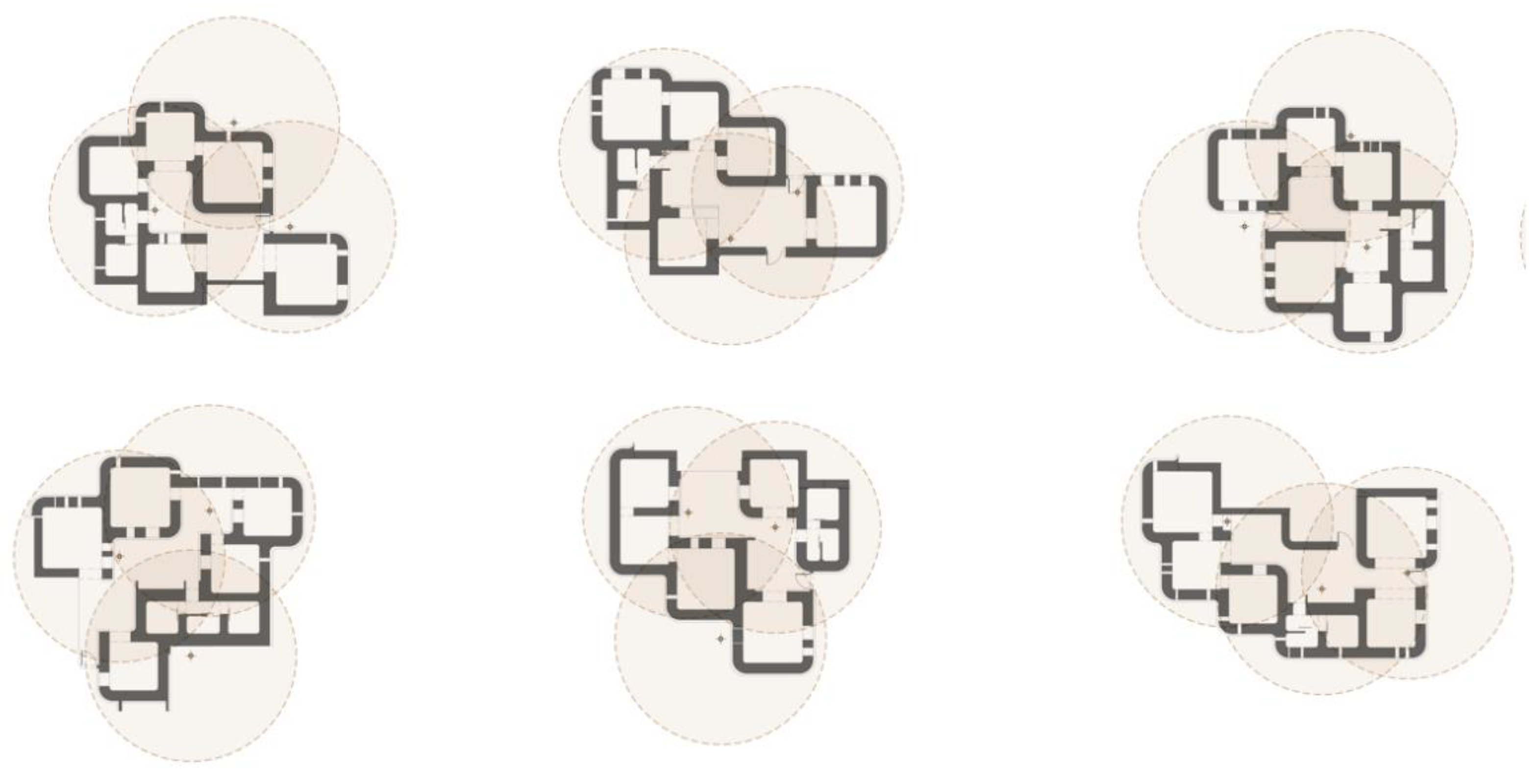

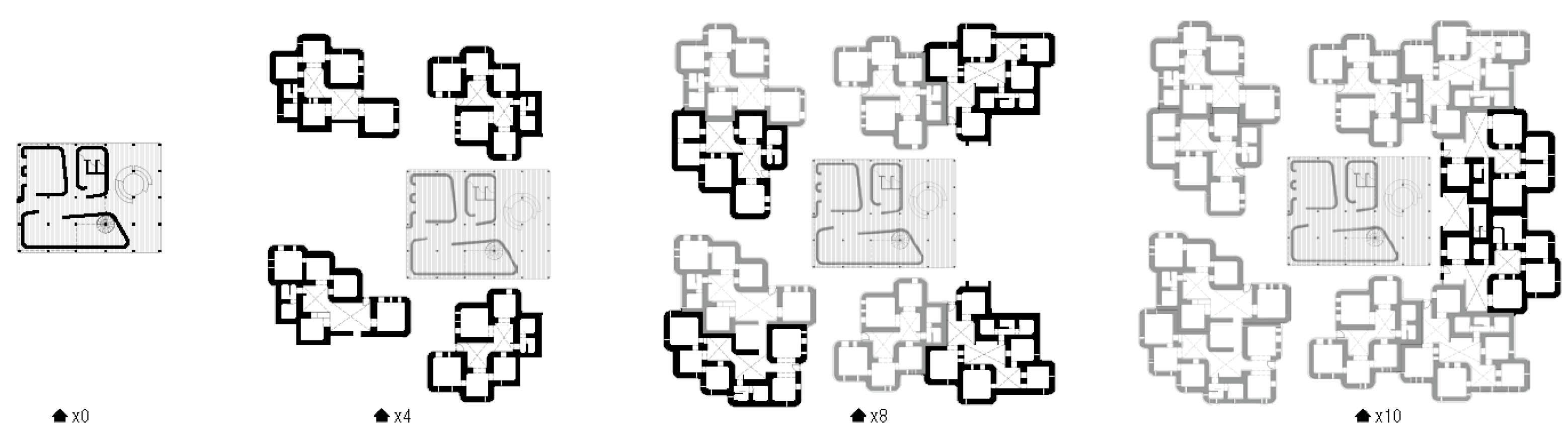

- Starting from the average size of a current dwelling (Figure 14a);

- Increasing the density by creating two units where previously there was one unit in the same area (Figure 14b);

- The individual dwellings are divided into functional modules (Figure 14c);

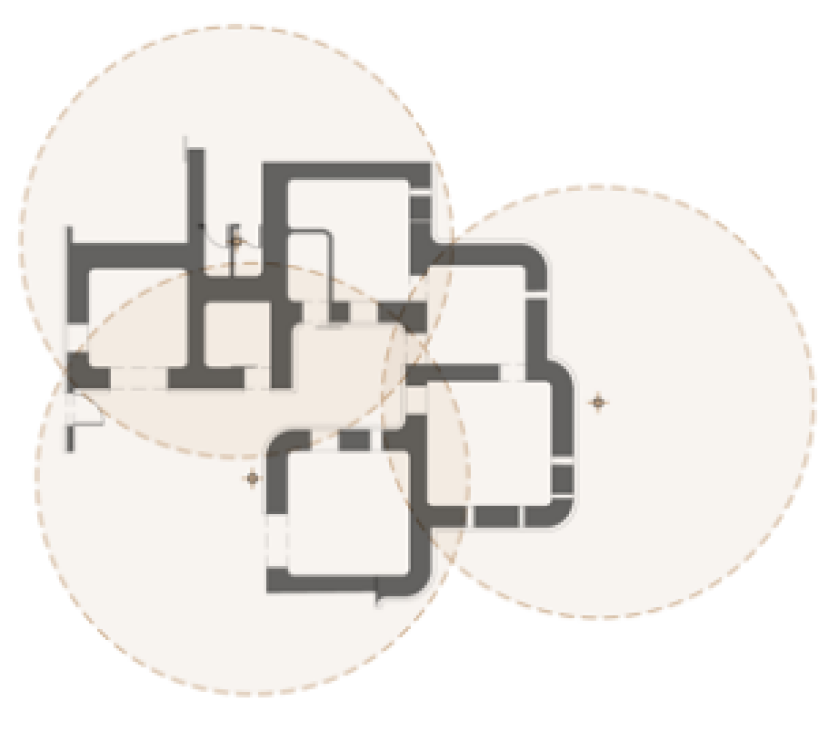

- The modules are then arranged to create the new house (Figure 14d);

- The housing units are aggregated to create a settlment (Figure 14e);

- The system is completed with the insertion of central community spaces (Figure 14f).

- -

- Those of an individual nature, such as bedrooms and bathrooms;

- -

- Family spaces, such as the living room, kitchen, and patios;

- -

- Those of the community.

4. Conclusions

5. Future Developments

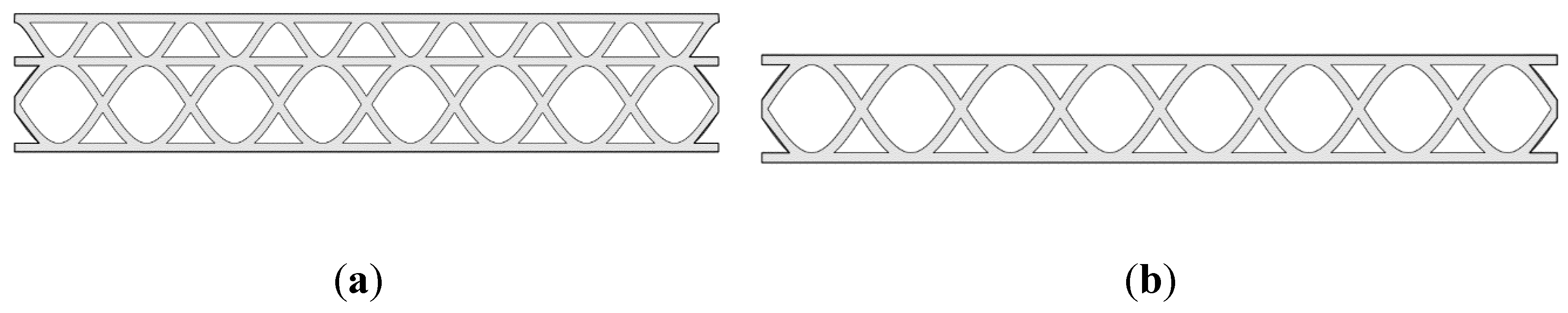

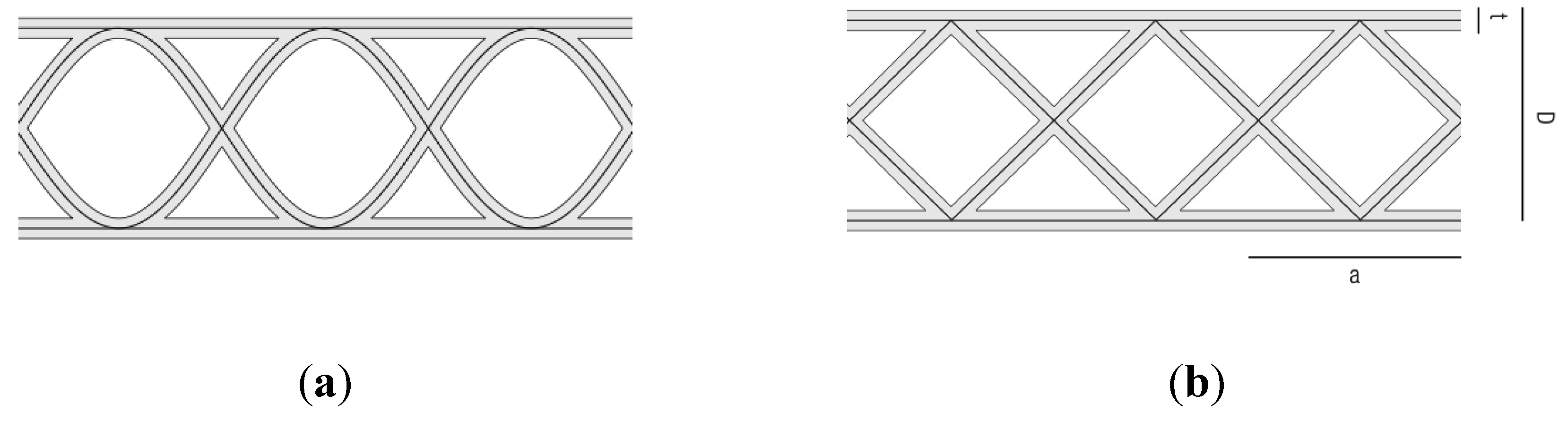

- Variation of wall strength with the variation of infill: defining different typologies of the wall infill in order to change it according to the different load conditions on the wall.

- Possibility of lightening the roof: designing an infill typology for the roof in order to lower the impact of the vault on the walls. This should greatly improve the design quality of the module in different ways: first, lower the amount of earthen mixture used to print one module, resulting in thinner walls and a better utilization of the space; second, further decreasing the printing time for each housing unit.

- Future scenarios of participatory design: the vision for the project is designing a housing system that can be easily customized by the people that will live it. 3D printing technology allows to have a direct connection between the machine and the software. A step forward to the current project would be to understand what other types of functional modules can be designed and how each one of them can be customized by the future owner, creating a catalog. This also implies developing an interface where people can design and request their custom houses based on their needs.

References

- Ratti, C.; Claudel, M. (2015). Open source architecture (pp. 18-22). London: Thames & Hudson.

- Paparella, G.; Percoco, M. (2022, June). 3D Printing for Housing. Recurring Architectural Themes. In International Conference on Technological Imagination in the Green and Digital Transition (pp. 309-319). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Skinner, B.; Lalit, R. (2023, January 17). Shares With Concrete, Less Is More. Demand changes can drive the future of zero-carbon concrete.

- Global cement and concrete association. (n.d.). The GCCA 2050 Cement and Concrete Industry Roadmap for Net Zero Concrete CONCRETE ROADMAP OVERVIEW DOCUMENT GCCA Concrete Future-Roadmap Overview.

- United Nations Environment Programme (2022). (2022). 2022 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction: Towards a Zero-emission, Efficient and Resilient Buildings and Construction Sector. www.globalabc.org.

- Gallipoli, D.; Bruno, A.W.; Perlot, C.; Mendes, J. (2017). A geotechnical perspective of raw earth building. In Acta Geotechnica (Vol. 12, Issue 3, pp. 463–478). Springer Verlag. [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M.; Kolokotsa, D. Passive cooling dissipation techniques for buildings and other structures: The state of the art. Energy Build. 2013, 57, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guamán-Rivera, R.; Martínez-Rocamora, A.; García-Alvarado, R.; Muñoz-Sanguinetti, C.; González-Böhme, L.F.; Auat-Cheein, F. Recent developments and challenges of 3D-printed construction: A review of research fronts. Buildings 2022, 12, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiusoli, A. (2018, September 29). La prima Casa Stampata in 3D generata con la Terra | Gaia | Stampanti 3D. WASP. Available online: https://www.3dwasp.com/casa-stampata-in-3d-gaia/ (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- Mario Cucinella Architects. (2021). Mario Cucinella Architects. Mario Cucinella Architects. Retrieved August 2, 2024, from https://www.mcarchitects.it/en/projects/tecla-technology-and-clay.

- Civera, G. TOVA is Spain’s first 3D printed building using raw earth (3dwasp.com), accessed online 03/08/2024.

- Wasp, 3D printed house_Gaia_WASP_overall view, Gaia press release. Press Kit Gaia 3d printed house - Dropbox, accessed online 03/08/2024.

- Corrazza, I. Dettaglio: Struttura in terra stampata in 3D del prototipo TECLA, Ravenna | Archello, accessed online 03/08/2024.

- Adobe Dome & Nubian Vault – Canelo Project, accessed online 03/08/2024.

- Carneau, P.; Mesnil, R.; Roussel, N.; Baverel, O. (2019). An exploration of 3d printing design space inspired by masonry. [CrossRef]

- Vaculik, J.; Author, F.; Gomaa, M.; Soebarto, V.; Griffith, M.; Jabi, W. (n.d.). Construction and Building Materials Feasibility of 3DP Cob Walls Under Compression Loads in Low-Rise Construction 3 4 Mohamed Gomaa ae.

- Sangma, S.; Tripura, D.D. Compressive and shear strength of cob wallettes reinforced with bamboo and steel mesh. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Struct. Build. 2021, 176, 710–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, E.; Moretti, M.; Chiusoli, A.; Naldoni, L.; de Fabritiis, F.; Visonà, M. Mechanical Properties of a 3D-Printed Wall Segment Made with an Earthen Mixture. Materials, 2022; 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarin, M. (n.d.). Plate Buckling Resistance - Patch Loading of Longitudinally Stiffened Webs and Local Buckling.

- Maja, M.M.; Ayano, S.F. The impact of population growth on natural resources and farmers’ capacity to adapt to climate change in low-income countries. Earth Syst. Environ. 2021, 5, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeoni, L.; Ferro, E.; Molinari, M.; Gerola, M.; Gajo, A.; Polastri, A.; Fanti, R.; Rossi, S.; Benedetti, L. (n.d.). Fondazioni a secco per edifici in legno AUTORI.

- Apis Cor. (n.d.). Construction can be fast, environmentally friendly, and affordable if we entrust all the complex work to smart machines.

| Materiale | Percentage by weight |

|---|---|

| Soil | 73% |

| Water | 25% |

| Wheat fibers (30-50mm) | 2% |

| Property | Strength value |

|---|---|

| Elastic modulus (E) | 22.9 MPa |

| Characteristic compressive strength (Fc’) | 0.62 MPa |

| Characteristic tensile strength (F’vk0) | 0.24 MPa |

| Density (γ) | 18 KN/m3 |

| Poisson’s ratio (ν) | 0.22 |

| Segment | Weight |

|---|---|

| 1 | 2.51 kN |

| 2 | 2.38 kN |

| 3 | 2.37 kN |

| 4 | 2.54 kN |

| 5 | 2.87 kN |

| 6 | 3.31 KN |

| 7 | 3.82 KN |

| 8 | 4.45 KN |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).