Introduction

Structure-function transcription studies revealed a high conservation of mechanisms across the three kingdoms of life. Transcription is a cyclic process divided into three significant steps: promoter DNA binding and RNA chain initiation, processive RNA chain elongation, and termination [

1]. Many features of each step were elucidated, including the nucleotide (nt) addition cycle, translocation, inhibition, pausing, backtracking, arrest, reactivation, processivity, and the property to proofread the RNA after misincorporation and recognizing DNA lesions [

2]. Also, a conserved architecture, active center, and similar fundamental transcription mechanism of cellular RNA polymerases (RNA pol) for all three life divisions have been described [

3]. They synthesize the RNA chain complementary to the DNA template strand from nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) substrates. The transcription process occurs spatially, forming biomolecular condensates, and RNA pol II can be incorporated into them [

2,

4].

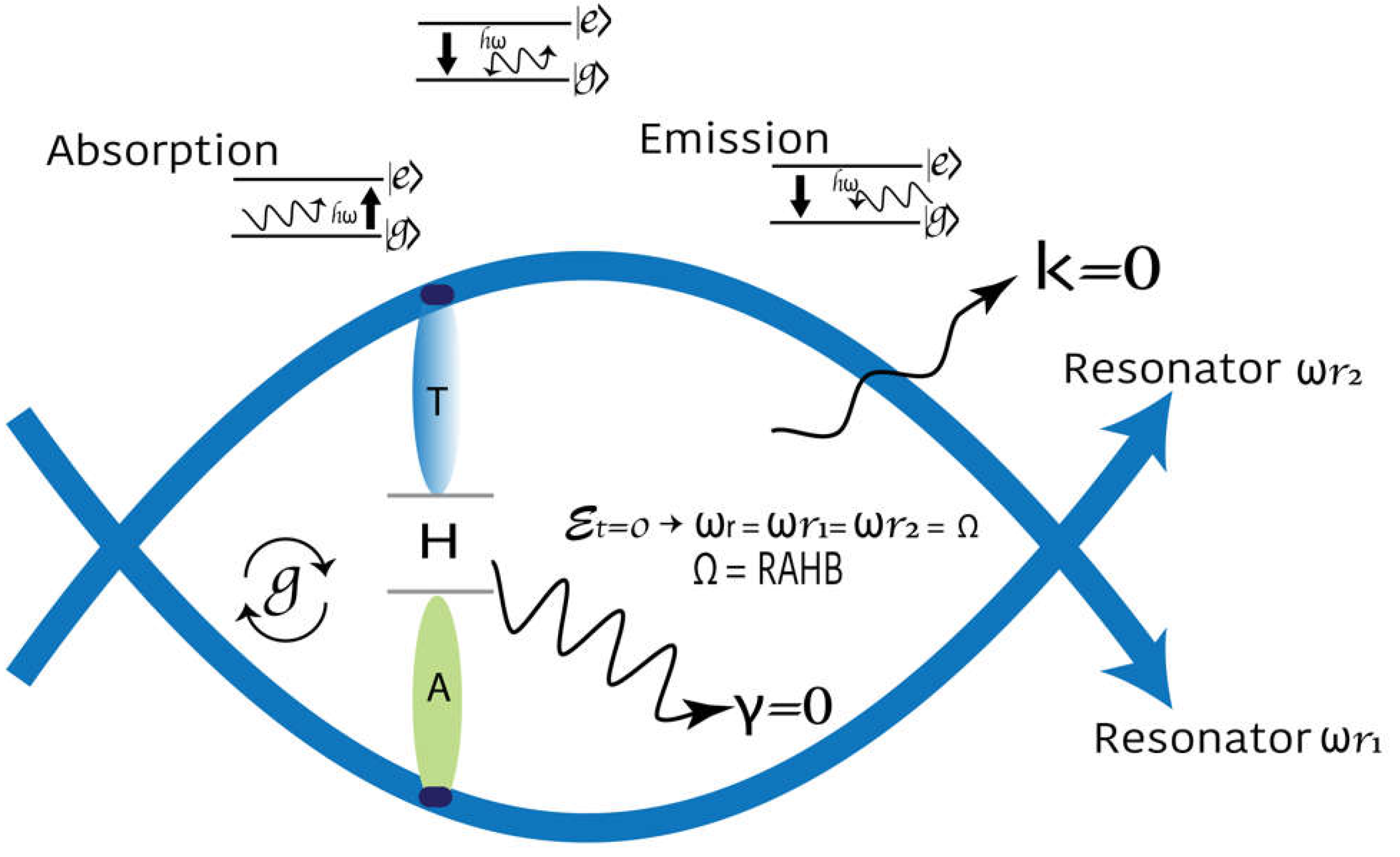

The qubit, the elementary block for quantum information processing [

5], is equivalent to a two-level quantum system (TLS) [

6]. There are systems that, naturally, already have suitable properties to be qubits, such as nuclear, atomic, molecular spins, electric dipoles [

7], and DNA base pairs (bp). Previously, we carried out a theoretical approach to DNA as a quantum computer [

8]. In DNA qubits, Adenine (A) and Thymine (T), Cytosine (C), and Guanine (G) are paired superconductors with the central Hydrogen bonds (H-bond) acting as a Josephson Junction (JJ). The quantum tunneling of H in the DNA and RNA molecules has been described [

9]. Qubits have to store information, be able to be manipulated effectively, and the data must be transferred from one place in the system to another (quantum bus). Maintaining the quantum coherence of qubits is a critical challenge. The system must be insensitive to external disturbances [

10].

The central idea for multiple qubit architectures is based on coupling them to a transmission line and selecting from the frequency at which qubits couple together [

11,

12]. These behave as non-linear resonators in which the fundamental and excited levels can be isolated. The general scheme of a coplanar microwave transmission line consists of a one-dimensional cable evaporated on an insulating substrate with two superconducting planes parallel to it on the same surface [

13,

14]. A finite transmission line is obtained by interrupting the central wire at two points to get a resonator that supports a quantized electromagnetic mode, behaving as a harmonic [

15].

Cavity Quantum Electrodynamics (cavity QED) studies the interaction of an atom as a TLS and the quantized electromagnetic field within an optical cavity [

16]. Inspired by the circuit QED, Circuit Quantum Electrodynamics (circuit QED) emerges, in which superconducting qubits and microwave transmission lines called resonators replace the atoms and the cavity, respectively [

13,

17]. A TLS and a coupled harmonic oscillator exist in the cavity QED and the circuit QED [

16,

17,

18].

Superconducting resonators are an indispensable element in the toolbox of circuit QED [

17]. A microwave resonator can be an excellent quantum data bus for controlling and coupling qubits and memory [

11]. In the cavity QED, the atom couples to the electromagnetic field through its electric dipole moment, while superconducting qubits have several coupling alternatives [

19]. Circuit QED is a specially-suited platform for quantum computation and quantum information processing due to its flexibility, scalability, and tunability [

20]. It has been experimentally demonstrated that there are strong couplings between superconducting qubits and a microwave resonator [

21].

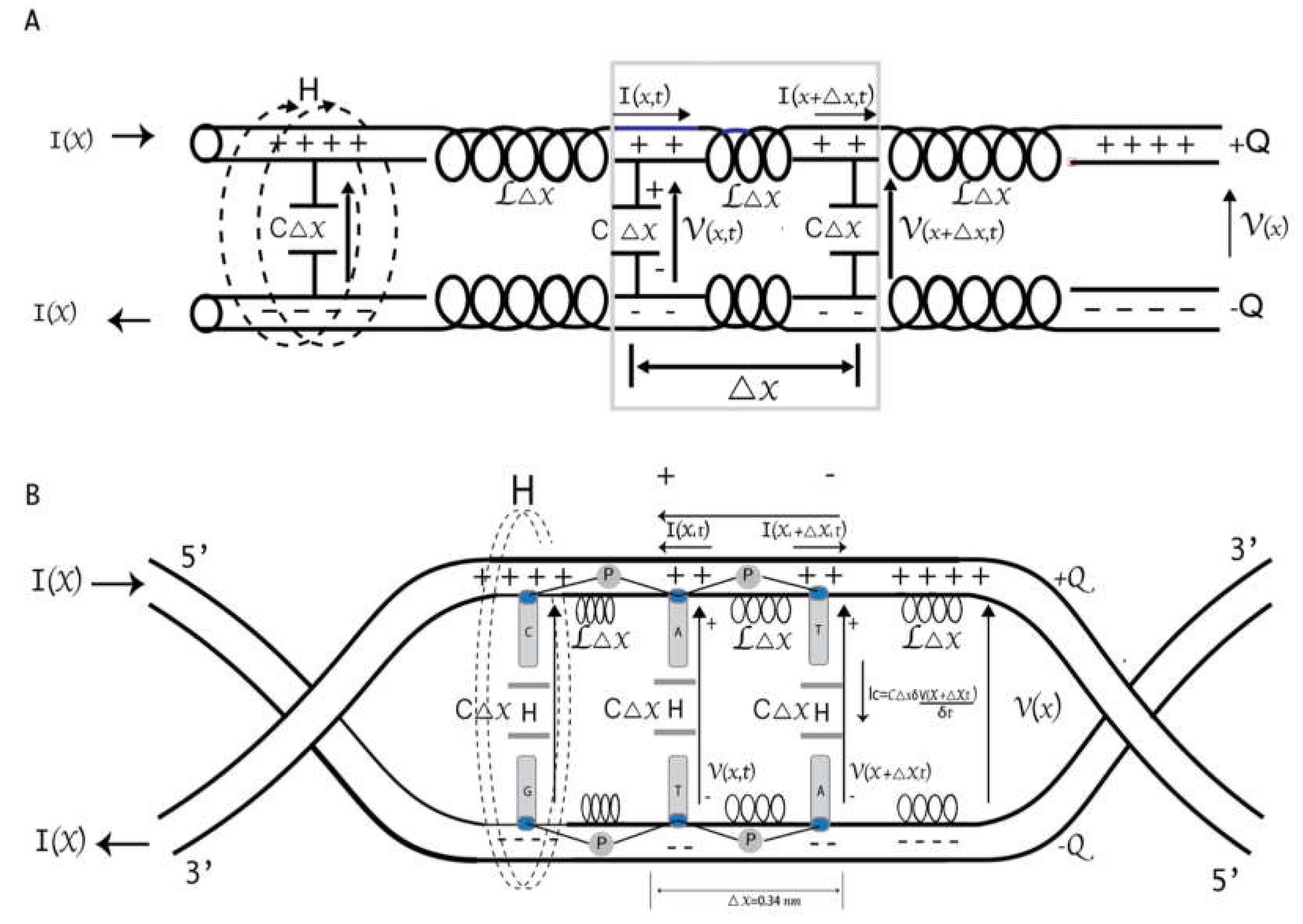

A big challenge related to programming molecular information processing systems is developing a circuit architecture that controls the stochastic states of individual molecular events. In this work, an electrical representation of DNA is carried out following the Quantum Electrodynamics Theory of Circuits and considering the results previously published by our team [

8]. A gene is described as a problem of a qubit capacitively coupled to two transmission guides subject to a harmonic forcing in the magnetic flux that passes through it for a frequency

and an amplitude

. A-T, T-A, C-G, and G-C bp are structurally similar to Radio Frequency Superconducting Quantum Interference Device (RF-SQUID), where each level is coupled to a different transmission line. In a resonant regime, the separation between the two energy levels of the qubit is in resonance with the frequency of the transmission lines. Entangled qubit-photon states are generated, and both system parts could exchange excitations. We consider genes as a combination of

n single-mode microwave resonators and cavities coupling in parallel. The Frequency matching can selectively obtain coupling between the phosphorylation pulse emitted by RNA pol II and any particular SQUID bp during transcription.

DNA and Transcription: Structural and Biochemical Studies

Genomic DNA is double-stranded. The H-bonded bases on each strand are stacked in parallel and run perpendicular to the sugar-phosphate backbone. Its x-ray diffraction pattern indicates that the bases are regularly spaced at 0.34 nm apart and have a relative twist angle of around 36° about the helical axis. Additionally, there are about ten pairs of bases per turn, as a complete turn of the helix is made every 3.4 nm [

22,

23]. The two strands have a backbone consisting of a repeating unit of sugar (deoxyribose) connected to a phosphate [

23]. Each bp triplet forms a codon that carries on the genetic code. However, most of the human genome does not code for proteins. These regions may provide RNA molecules and transcription factors’ specific sequences of binding sites and exert regulatory functions [

24]. When focusing on the backbone of the DNA helix, two helical grooves exist with different widths, known as the minor and major grooves. The minor groove describes the space between the two antiparallel DNA strands that run closest together, while the major groove describes the space where they are furthest apart [

22]. These specific dimensions describe the B form of DNA, the primary form in most cell DNA stretches [

23].

The eukaryotic transcription cycle is roughly divided into three major phases (promoter DNA binding and RNA chain initiation, processive RNA chain elongation, and termination). The initiation undergoes various steps, recruiting multiple cellular factors, the mediator complex, and the RNA pol II to form a pre-initiation complex (PIC) at core promoter sequences. PIC composition is identical at all yeast promoters and is the rate-limiting step for transcription [

25]. The promoter DNA strands are separated, allowing RNAP II to access the DNA template strand and begin the RNA synthesis. All cellular RNA pol II forms a stable elongation complex (EC) with the DNA template and RNA transcript for transcription elongation [

26].

Eukaryotic polymerases comprise an evolutionarily conserved catalytically competent ten-subunit core and up to seven additional subunits on the periphery. The C-terminal domain (CTD) of the largest subunit of RNA pol II has a repeated heptad motif (Tyr

1Ser

2Pro

3Thr

4Ser

5Pro

6Ser

7) [

27]. The copy number generally increases with the organism’s complexity: 26 in budding yeast and 52 in humans. CTD’s dynamic phosphorylation and de-phosphorylation play a critical role at every stage of transcription and coordinate the stage-specific association and release of cellular factors (

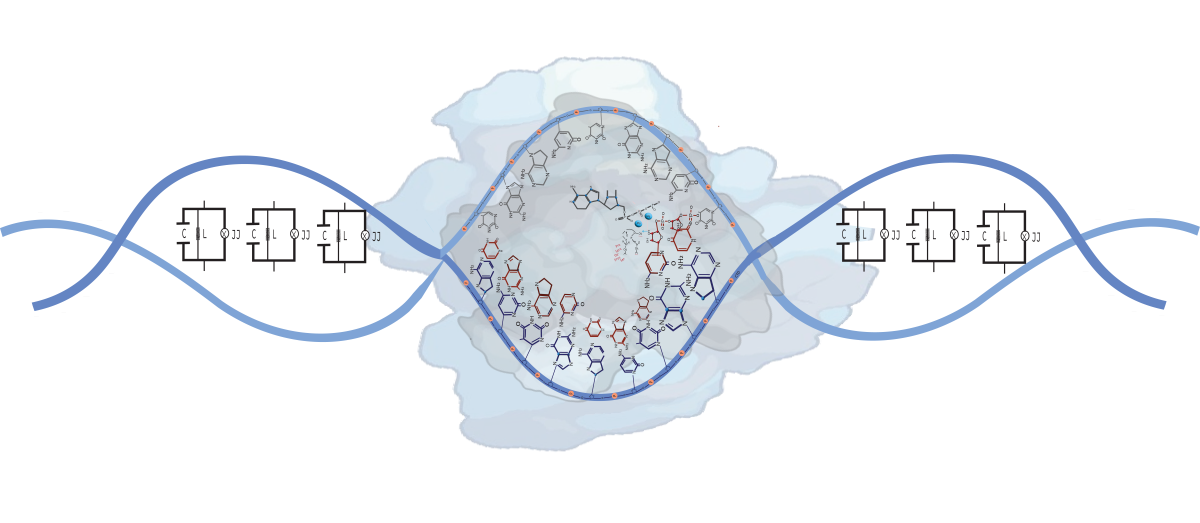

Figure 1A) [

28,

29]. For example, transcription initiation and promoter escape at the 5′-end is facilitated by Ser5 phosphorylation (Ser5P) for Kin28/Cdk7. The elongation is partly due to Ser5P by Srb10/Cdk8 and Ser2P by Ctk1/Cdk9. The termination and the 3′-end processing are because of the Ser2-Ser2P transition by Bur1/Cdk9 [

30,

31]. A similar phosphorylation reaction catalyzed by protein kinases regulates the biological activity of many proteins.

Most promoters contain two main recognition elements: −35 and −10 hexameric boxes with consensus sequences TTGACA and TATAAT, separated by a region of 17 ±1 bp called a spacer [

32,

33]. It was shown that the −35 element interacts with the σ4 domain primarily by inserting a helix-turn-helix (HTH) into the DNA major groove. In contrast, an α-subunit C-terminal domain (α-CTD) interacts with the DNA minor grove from −43 to −38 and binds just upstream of the σ

704 [

34].

During elongation, RNA pol II maintains an almost constant size (12±1 nt) of the transcription bubble and 8±1 bp RNA–DNA hybrid until it reaches the termination signal [

35]. This requires unwinding the downstream DNA duplex and separating the RNA product from the DNA template at the end of the hybrid duplex. RNA pol II catalyzes the DNA-directed addition of nt to the growing RNA chain. It selects the correct nt, adds it to the RNA 3′-end, and releases a pyrophosphate (PPi) ion during the nt addition cycle (NAC). Residues contacting the nt are conserved in all cellular RNA polymerases, consistent with a universal nt selection and incorporation mechanism [

36]. The NTP substrate binds transiently to an open active center conformation. Structural information on an RNA pol II EC revealed a nine-base pair DNA-RNA hybrid duplex emanating at right angles to the incoming DNA from the active center cleft at the floor [

2,

37,

38].

In the EC, incoming (downstream) DNA is unwound before the active center, allowing the template single strand to reach the active site, and is rewound to form the exiting (upstream) DNA duplex. Within the unwound region (the transcription bubble), the growing RNA is attached to the catalytic site with its 3′-end and forms an eight to nine-bp hybrid duplex with the DNA template strand. The DNA-RNA hybrid duplex is the distinguishing feature of the EC and binds within the active center cleft to adopt a conformation close to an A-form duplex [

26].

Transcription processivity refers to the property of the polymerase that remains associated with an actively transcribed DNA template to reach the end of the transcription unit successfully. Processivity is achieved, to a large extent, by the high stability of the EC, which mainly results from the tight binding of the DNA-RNA hybrid. Spt5 spans the pol II cleft from the clamp on one side to the lobe and protrusion on the other side. The Spt5 NGN domain binds to the coiled coil of the clamp in all polymerases [

36]. In addition, Spt5 may contact upstream DNA and the non-template DNA strand in the transcription bubble [

39]. Interactions between the positively charged Spt5 surface and the negatively charged DNA non-template strand may help prevent the transcription bubble’s collapse. The models are consistent with biochemical data, indicating a universal binding mode to all polymerases.

A-T, T-A, G-C, and C-G Base Pairs: RF SQUIDs. The Hamiltonian Scheme

Superconducting qubits have emerged as a leading technology platform for quantum computing [

11,

40]. Flux qubits are superconducting qubits that exploit magnetic flux through a superconducting loop. They consist of a superconducting ring interrupted by one or more JJs and crossed by a magnetic flux based on the Josephson Effect [

11]. The qubit’s state is manipulated by varying the magnetic flux enclosed in the loop. In flux qubits, the quantum state is encoded in the persistent current flowing through the superconducting loop. The loop’s JJ allows external magnetic fields to control and manipulate the qubit’s state. Suppose an external oscillating flow of fixed frequency and variable amplitude is applied. In that case, the qubit can be forced by generating oscillations in the populations of its two energy levels through the Landau-Zener-Stuckelberg Transitions.

In phase qubits, quantum information is stored in the relative phase difference between the two sides of the Josephson junction. The qubit can undergo coherent rotations between its quantum states by applying external microwave pulses [

41]. One of the most used systems in Circuit QED is the charge qubit (Cooper pair box) coupled through the electrical component of the field to a superconducting coplanar waveguide resonator [

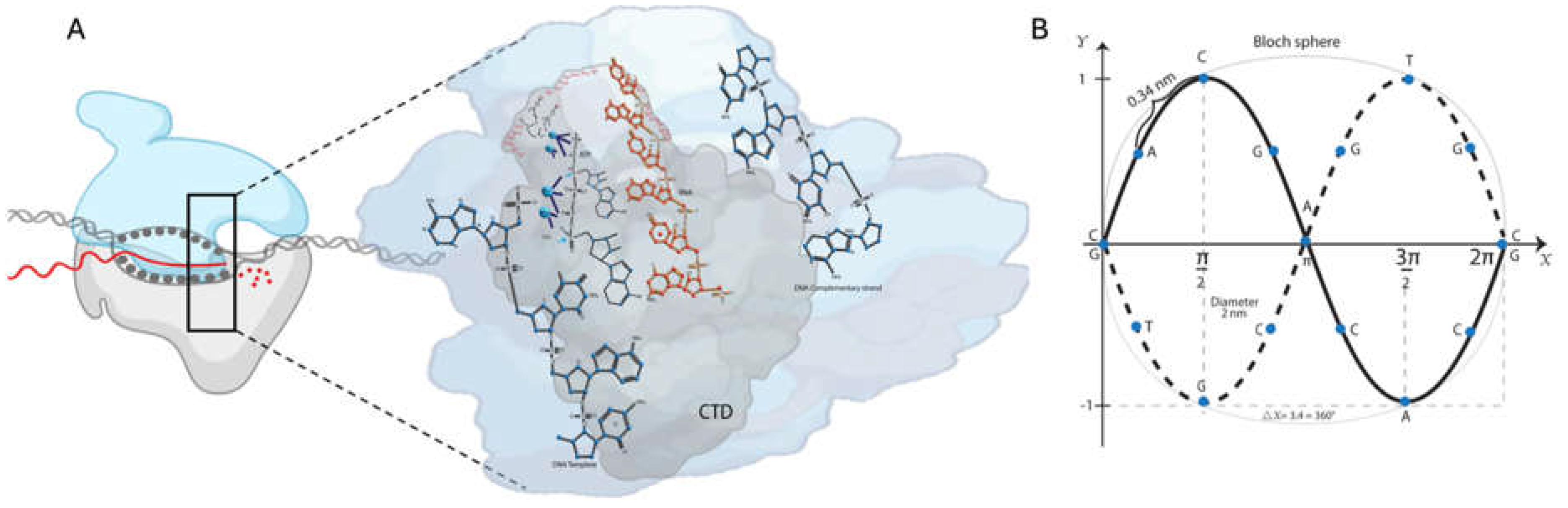

40]. Recently, many studies have highlighted the central role of transmon qubits (

Figure 2A) in quantum computing [

19]. In them, the energy levels of the superconducting island are controlled by an external magnetic field that induces a magnetic flux across the JJs, affecting the superconducting phase difference [

13]. By tuning the magnetic flux, the energy levels of the transmon qubit can be adjusted, allowing precise control of the qubit’s operations [

11].

Highly anharmonic energy spectra, with a significant energy difference between consecutive levels, are crucial for reliable and long-lasting qubit operations, as they ensure that the qubit remains well-defined and stable during quantum calculations. In a previous study, our working group established the role of DNA as a perfect quantum computer by characterizing Adenine (A), Thymine (T), Cytosine (C), and Guanine (G) nitrogenous bases as superconducting islands. In addition, we defined DNA qubits by combining the quantum state of the composite system with classical information:

A-T and C-G are superconducting qubits with intrinsically quantum behavior. They have quantized energy levels, so their separation is more significant than thermal fluctuations and can be in superposition states. The JJ introduces anharmonicity to the system [

11], thus obtaining non-equispaced energy levels. Each transition has a distinct frequency because of the decreasing energy spacing as the quantum number progressively increases. If externally applied a magnetic flux, the double-well potential and the two eigenfunctions become symmetrical while antisymmetrical superpositions of the two basis states. In these superconducting rings, a single total wave function describes the state of all electron and hole pairs in the condensate:

.

single electron and hole pair momentum.

is the probability density of finding an electron and hole pair in a given volume

of the phase associated with each electron and hole pair in space.

Because this wave function must be unvalued, the accumulated phase change (

) when traveling a closed path around the year must be a multiple of

:

Because the RNA pol II contacts only one element of the pair (classical information) in the template strand, we considered the number of aromatic rings to get one of the four Bell states:

Purines , Pyrimidines , then

, and

, then

or , and

or

, , , and

A JJ forms the foundation of a SQUID. However, these junctions also present an internal capacitive effect because they are constituted by two superconducting electrodes separated by an insulator [

11]. The JJ can be considered a linear harmonic LC circuit with nonlinear inductance. Two types of SQUIDs are commonly used in quantum computer applications: a DC SQUID, which contains two parallel junctions, and an RF SQUID, which includes just one junction.

In DNA qubits, the central H-bond, acting like a JJ, forms the foundation of the RF SQUIDs (

Figure 2B). The H-bond can induce strong inter- or intra-molecular electronic coupling by enhancing resonance, electron delocalization, or planarizing the conjugated backbone.

Nitrogenous (N) number three (N3) of a T in T-A bp has a lone pair of electrons as part of the

-cloud. The N1 in A uses the lone pair to attract the H attached to the N3 of T. Similarly, in C-G bp, the N3 in C uses its lone pair of electrons to form an H-bond with the N1 of G. Then, in our previous work, we explained, using physics approximations, how electrons interchange a biological quantum of energy to form electrons and hole pairs in the JJ. The electron (

) three (

) with the momentum

emits a Biology boson (

) to

losing the momentum

and occupies the position of the hole (

) one (

) with momentum

. Then,

through the Tunnel Effect, passes through the barrier (NH--N) to the position of

, where there is now a hole. Please check

Figure 4 in the reference [

8].

The first Josephson Equation

describes how the tunneling current depends on the two superconductors’ phase difference. The second Josephson equation

represents the time evolution of the phase difference given an external voltage [

11].

is the potential difference in JJ. These two equations describe the temporal phase evolution of the two superconductors. If a constant voltage is applied to a JJ, the phase difference will evolve linearly in time (AC current). As opposed, if we use no external voltage, the phase difference becomes constant (constant supercurrent despite no external voltage) due to the phase coherence of the pairs. It is known as the DC Josephson Effect.

The first term can be disregarded because it is a constant factor while the terms of order can be disregarded because of being small.

The Hamiltonian is an energy operator containing kinetic energy

, and a potential energy of the form

.

The Hamiltonian of a qubit with a single JJ is given by

: flow in the JJ

: external magnetic flux,

: capacitance

: Inductance

: Josephson energy

: magnetic flux quantum

: JJ energy

Equation (1) is the Hamilton equation. Following the first quantization procedure, the two conjugate variables and are promoted to non-commuting operators

The first two terms in Equation 2 represent harmonic oscillators, and the third is the anharmonicity.

Introducing the standard annihilation

and creation

operators is useful.

The action of is to create a quantized excitation of the flux and charge degrees of freedom of the magnetic and electric fields. It creates a photon of frequency stored in the circuit.

In function of

and

:

Then, the Hamiltonian in Equation 2 combines in:

With the new frequency and the anharmonicity .

Please note that the Hamiltonian represented in Equations 2 and 3 corresponds to our qubit proposal based on the DNA characteristics and differs from those described in other works (

Figure 2B).

DNA Backbone AS A Finite Transmission Line with Distributed Parameters. The Hamiltonian Scheme

A transmission line is a structure of uniform geometry used to transport electrical signals or RF energy efficiently from one point to another [

11]. It is also a medium that propagates information through electromagnetic waves at very high frequencies [

42]. Because it behaves like a cable that spreads energy, it can be analyzed like a quantum oscillator electrical circuit based on its frequency response. The circuit is considered a line with distributed parameters at high frequencies since it has dimensions comparable to the wavelength [

43]. Thus, the circulated current’s amplitude and phase differ at every point. The wavelength is very short for high frequencies, so the transmission lines behave like resonant circuits for a specific frequency range.

Two parallel conductors form pair lines. Its various variants are used in telephony and data transmission [

44,

45]. Electromagnetic energy propagates around the conductors of the line. If a voltage

is applied to a pair line, an electric (

) field is generated between the conductors as opposite charges accumulate. The

makes an electric current

flow through the line’s conductors terminated at a load impedance (

). This current also generates a magnetic

field around the conductors. The direction of the current and fields is reversed in each half-cycle of the voltage [

45]. By multiplying

by

, we obtain the induction magnetic vector (

), and then, by integrating

over a plane parallel to the wires, we get the magnetic flux (

) that “joins” the circuit.

The mathematical definition of a circuit inductance is

. If we have a transmission line length

units long, and if that line has a distributed inductance

, then the inductance is just

. Two conductors with charge

separated by a distance generate a potential difference (

).

in every section of a transmission line length

. Where

is the lineal distribute charge. The basic parameters describing any transmission line are its capacitance and inductance per unit length (C, L), its characteristic impedance (

), and the mode frequency (

) [

21]. These parameters are related by:

In most transmission lines, the electric and magnetic fields point purely transverse to the direction of propagation, called Transverse Electromagnetic Waves (TEM) [

46]. We can distinguish between infinite, semi-finite, and finite transmission lines. The latter is obtained by interrupting the central cable at two points so that a resonator that supports a quantized electromagnetic mode behaving like a harmonic oscillator is obtained. A resonator is any structure that can trap oscillatory electromagnetic energy so that it escapes slowly or not at all [

11]. Boundary conditions restrict the wave structure allowed inside to patterns with integral numbers of half or quarter wavelengths along any propagation axis [

45]. Therefore, only certain discrete resonant frequencies

can be present. All resonators dissipate energy, but there is no dissipation if the resistive element is in series at zero current or parallel at zero voltage. Typical TEM resonators are terminated with lossless elements.

Resonators are widely used to manipulate signals and energies. They could function as bandpass filters that eliminate all frequencies from a signal except those close to the desired resonant frequency (

) or as bands-stop filters that eliminate unwanted frequencies close to

, and let all frequencies pass. Other applications included effectively step-up transformers to increase voltages or currents to levels sufficient to couple all the energy into the reflected loads without reflections [

21].

Characterizing single-stranded DNA as a transmission line is also of great technological interest due to DNA’s ability to form versatile programmable structures. Single-stranded DNA can exhibit rich electrical properties. The backbone structure of DNA is formed by phosphate groups and pentose sugars (deoxyriboses). Deoxyriboses are attached to the nitrogenous bases via similar C-N bonds [

47]. The negative charges at the phosphate groups connect the base pairs and give structural support for the double helix. Considering energetic and spatial separation between sites, multiphonon-assisted hopping of small polarons between the next nearest neighbors of the DNA molecular wire was suggested as the transport mechanism responsible for the solid high-temperature dependence of the electrical conductivity in DNA [

48]. Our DNA wire model has connections between successive base pairs, which are the only sites included. Porath and Cols demonstrated that the sugar-phosphate backbones nor the specific bp sequence mediate the long-distance conduction in DNA [

49]. Different experimental techniques were employed to study the electrical conduction through single DNA molecules, but the conduction mechanism, especially in long DNA molecules, is far from being established.

Figure 2C shows a schematic representation of DNA based on the model of parameters distributed in a transmission line. The length of the line is proportional to the total capacitance and inductance. In this model, the phosphate groups in the DNA backbone carry the inductive effect, while the bases have the capacitive effect. Since it is a superconducting circuit, we will ignore the electrical resistance and magnetic fields within the strands, which are expelled due to the Meissner effect [

8,

50].

Using the Telegrapher equations, we can obtain the transmission line equation and assume the DNA strand acts as a lossless line with

and

, where R and G are the resistance and shunt admittance per unit length [

51]. The first equation

explains the voltage dependence the distributed inductance

multiplied by the time derived from the current flowing in the line at one point. The second equation

explains that the current loss as we go down the line is proportional to the distributed capacitance

multiplied by the time rate of the voltage change in the line.

An LC oscillator is characterized by its inductance L, capacitance C, angular frequency

, and impedance

. The oscillator energy is given by:

where by Faraday’s law:

Equation (5) is an LC harmonic oscillator equivalent to the coordinate mechanical harmonic oscillator

and

Then,

Introducing the creation and annihilation operators (

and

)

where

with

and

is the zero-order energy or null energy.

creates a quantum excitation of flow and charge equivalent to the electric and magnetic Fields (a frequency photon inside the circuit).

We can generalize the result for a transmission line in the x direction and length d. The energy associated with each capacitor is , and to each inductor . Where is the variable flow associated with node n and the conjugate variable is the charge at node n.

Then, the Hamiltonian for the discrete linear transmission resonator associated with

Figure 2C is

and

: the variable inductance and capacitance associated with each node n and flow

.

In the continuous limit, considering the size of a unit cell that tends to zero:

and with y the linear density of capacitance and inductance.

Defining a continuous flow field as

and the charge

. Taking the

and

constant, the Hamiltonian for a continuous linear transmission resonator:

where

The charge is the generalized canonical moment of the flow with the voltage.

Using the information above, we obtain the wave propagation equation along the linear transmission resonator

It is the speed of light in the biological medium of DNA.

The Equation (7) solution is expressed as a linear combination of normal nodes of a size

.

with

a differential equation of an oscillating function in time at the frequency node

with amplitude

, wave vector

, and phase

.

The Hamiltonian given by Equation 6 can be expressed as a discrete Hamiltonian:

This Hamiltonian (Equation 8) represents the sum of simple harmonic oscillators. With as the total capacitance of the resonator and the conjugate charge .

Following the quantization procedure with the variables

and

, we define the creation and annihilation operators:

where

the characteristic impedance of the m node and

.

Then, the Hamiltonian given in Equation 8 finally transforms into:

With

, and

is the frequency.

DNA AS A Quantum Electrodynamic Circuit. The Hamiltonian Scheme

A coplanar waveguide’s (CPW) geometry allows for increased electromagnetic energy density and coupling [

20]. The strong coupling permits operations to be carried out on the qubit and even entanglement of multiple qubits in the same cavity (Blais et al., 2021). In particular, by taking advantage of the excellent connectivity and scalability of the two-dimensional CPWs (TD-CPWs), researchers have successfully utilized circuit QED to realize high-efficiency preparation of entanglement of up to 20 qubits and high-fidelity cross-resonance two-qubit gates for achieving a quantum volume as large as 64 qubits. For conventional superconducting resonators in circuit QED, including both TD-CPWs and three-dimensional cavities, the electromagnetic fields inside are standing waves determined by boundary conditions, which results in a location dependence of the fields’ amplitude [

21]. In circuit QED, resonant microwave cavities are replaced by certain types of integrated circuits that are essentially sections of microwave transmission lines [

19]. The photon energy is concentrated in and around the center line. If superconducting materials are used for the circuit, the resistive losses can be suppressed, and the system’s losses and dephasing would be limited only by the system properties [

11]. An approach for mitigating the effect of these losses is to lower the ratio of the electric field energy stored at interfaces and surfaces to the energy stored in a vacuum by using three-dimensional microwave cavities or three-dimensional resonators rather than planar circuits [

17,

52]. It is a new paradigm for quantum information processing in which information is stored in a cavity.

Following an introduction to these fundamental concepts that are at the heart of circuit QED, the effective Hamiltonian for our DNA model can be represented as

where,

is the Hamiltonian of a flux qubit with a single JJ (A-T, T-A, G-C, or C-G).

and

represented the Hamiltonian of the two single-stranded DNA separately. To complete the effective representation of the Hamiltonian in DNA,

represents the interaction between the qubit and two-stranded DNA.

, the cavity losses, and the decay rate.

, decoherence, or decay of the two-level system.

As A-T and C-G are superconductors, their properties would limit the system’s losses and dephasing (.

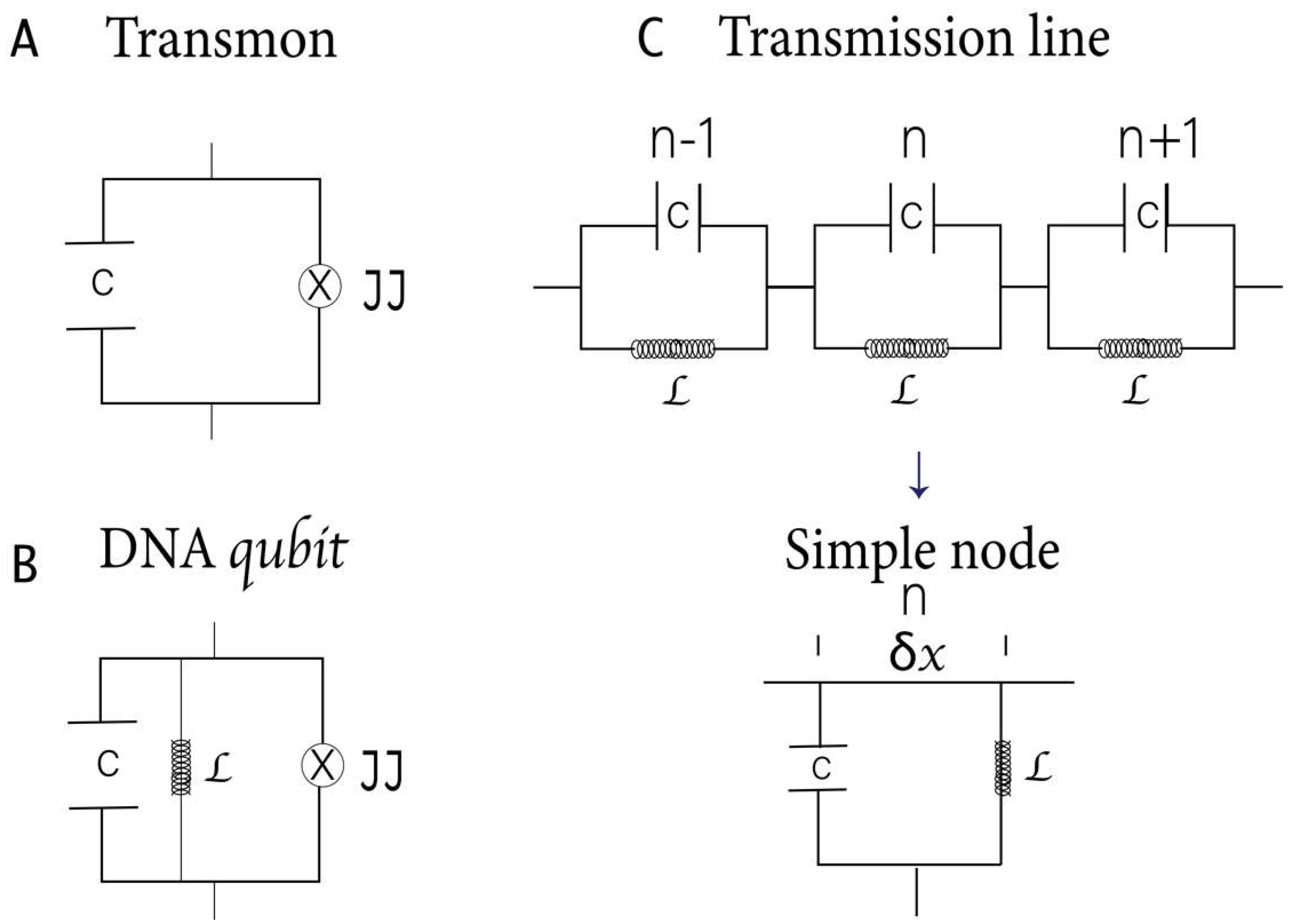

According to the Hamiltonian, when a qubit is strongly coupled to a cavity, it produces a specific signature when tuned into resonance. The coherent oscillation between two quantum states is known as Rabi oscillation and the frequency as the Rabi frequency

(

Figure 3). The

is proportional to the interaction energy of the TLS with the electromagnetic field [

53]. For a flux qubit coupled to a single mode of the electromagnetic field of a transmission line that acts as a resonator, the system’s Hamiltonian consists of three parts: the qubit term (

), the electromagnetic field term confined in the resonator (

), and the Rabi-type interaction term (

).

resonator resonance frequency.

, but in DNA under the ground conditions . At this point, we consider the oscillator at a fixed instant.

Where corresponds to the minimum energy or the fundamental state ()

corresponds to the energy difference between the two levels for

,

In the absence of damping, the Hamiltonian can be readily diagonalized. The detuning parameter is . In the zero-detuning case .

, and are the Pauli matrices.

and photon creation and annihilation operators.

Intensity of the coupling between the qubit and the electromagnetic field (the coupling rate of the two systems). It depends on the strength of the electric or magnetic field at the system site, its dipole moment, and the system’s properties [

52].

where

and

are the electric and magnetic field amplitudes.

Expanding the interaction term in terms of the rise and fall operators

A TLS and a harmonic oscillator are coupled in a circuit QED [

21]. The circuit can operate in two distinct strong coupling limits: the resonant regime and the off-resonant dispersive regime. On resonance, the separation between the two energy levels of the qubit resonates with the transmission line frequency. Entangled qubit-photon states are generated, and both system parts can exchange excitations without losing energy [

11]. In an ultra-strong coupling regime, the coupling intensity reaches values comparable to the resonator frequency, rendering the Jaynes-Cummings Model invalid. In the dispersive regime, the transmission line frequency differs from the qubit energy levels separation. In this situation, the energy levels of the qubit will depend on the state of the photons and vice versa. Consequently, the resonator could obtain information about the qubit’s state and couple multiple qubits together [

54].

Circuits capable of processing molecular information have been developed to control complex behaviors in biological and biochemical systems. In the DNA ground state, each nitrogenous base is coupled to a transmission line in resonance with the H-bond that joins it to its complementary base connected to a second transmission line. When RNA pol II emits pulses at the end of the transmission line, the system enters a dispersive regime. It is a sub-regime of the Jaynes-Cummings Model that allows measurements of the qubit’s state acting on the resonator. The energy levels of the qubit are normalized depending on the state of the resonator and vice versa [

54]. The state of the qubit is determined by varying the waveguide frequency until it matches the new frequency of the resonator. It also allows manipulation of the qubit by forcing the resonator with a signal sent through the waveguide that has a frequency close to the natural frequency of the qubit.

This work approaches the DNA gene structure as the lineal combination of circuits-QED. Each qubit level of a flux qubit is coupled to an independent resonator. The frequency of the qubit is similar to that of the resonators it has been connected to. For a flux qubit coupled to two modes of the electromagnetic field of a transmission line that acts as a resonator, the system’s Hamiltonian consists of three parts: the qubit term (

), the electromagnetic field term confined in the two resonators, and the Rabi-type interaction term (

). (modified from Equation 9):

In the DNA ground state,

In DNA, A-T, T-A, C-G, and G-C qubits are coupled to a virtual cavity defined by two resonators. This constitutes the DNA basic unit. The difference between the system’s energy levels in the DNA ground state is

due to the movement of electron and hole pairs in the aromatic ring without an external force [

8]. A-T and C-G are strongly coupled to the resonators. This firm coupling limit allows a large number of operations to be performed during the lifetime of the quantum state. The bps oscillate coherently between two quantum states in the phenomenon known as Rabi oscillations. The oscillation frequency is the Rabi frequency and is proportional to the interaction energy of the qubit with the photon electromagnetic field. Each bp level can be tuned with an external electric or magnetic field such that a certain level splitting coincides with the cavity photon energy

Figure 4.

Analyzing Equation (10), we can estimate the average field strength using the integral of the field amplitude over the space volume delimited by the two resonators. DNA spiral diameter is around 2 nm. Thus, we assume that the space dimensions give us

, where

is the sphere´s volume, and

is the radio. Taking a space average and setting that the integral of the field amplitude is equal to the zero point energy (

and

) [

52]:

Then,

and

, for the electric and magnetic fields, respectively.

In the following section, we will describe the theoretical basis for DNA Transcription and compare this process to the dispersive detuning regime.

Quantum Description of Transcription

Although much progress has been made in elucidating the critical events during transcription, what needs to be addressed is that the process takes place strictly in a spatially defined manner. We still need to know how the transcription spatial organization is achieved. A physiochemical phenomenon called biomolecular condensates is partly formed through phase separation to achieve spatiotemporal regulation of some biological processes [

55,

56,

57,

58]. Emerging evidence revealed a fundamental role of phase separation in regulating the transcriptional events in every step of a transcription cycle (

Figure 1A) [

59,

60].

Multivalent interactions are the molecular driving forces underlying phase separation in biomolecular condensates. They involve intrinsically disordered regions, structured, repeated modular, and oligomerization domains [

61]. Some molecules function as scaffolds to assemble phase-separated structures, whereas client components are recruited to the condensates by directly binding to scaffolds [

55]. In general, modular interaction domains in evolutionarily conserved protein segments create multivalency that facilitates the engagement of multiple binding complexes and the formation of dynamic interacting networks to promote phase separation [

60]. In many proteins, repeated sequence elements such as tyrosine, glycine, and serine have provided multivalency to undergo phase separation and enable the formation of biomolecular condensates [

29]. Unlike the classical description of transcription proceeding in a fashion that RNA pol II tracks along the relatively static DNA template strand to synthesize the nascent RNA, the phase separation model for transcriptional control allows for the description of a quantum model of transcription.

RNA pol II can be incorporated into transcriptional condensates with different components and has distinct functions depending on those components [

58,

61]. Transcription bubble translocation along the DNA requires rotation of the RNA pol around the axis of the DNA double helix or DNA twisting. The linking number density has been calculated using the equation:

where

is the accumulation of a rotational angle,

is the distance in

,

is the rotation angle of the RNA pol, and

the DNA rotation at the RNA pol site. Based on DNA supercoiling-transcription interplay, experiments have shown the maximum RNA pol II translocation rate or velocity is

. [

26].

The ability of pol II as the scaffold for the PIC arises from its CTD, which is flexible and highly disordered. Accumulating evidence suggests a close link between CTD and phase separation in promoting efficient transcription initiation. The role of CTD phosphorylation in activating co-transcriptional capping is well-established [

31]. Thus, the favorable regulation of CTD in condensates is reversibly controlled depending on CTD phosphorylation [

29]. It has a switch-like function in determining the partitioning of pol II into different condensates as transcription progresses from one stage to another. For example, the transition between initiation and elongation is associated with Kin28-mediated phosphorylation of Ser5 within the heptapeptide repeats [

27]. Hence, it raises an essential question of whether phosphorylation is the transcription’s driving pulse.

In phosphorylation reactions, the side chain hydroxyl groups on specific proteins’ serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues are modified with the gamma phosphate from ATP. The conversion of a neutral hydroxyl group to a charged phosphate represents a theatrical change in the protein’s local architecture [

62]. Thus, it may behave very differently when phosphorylated regarding its overall conformation and ability to bind to small molecules or other proteins.

The phosphorylation of alcohol groups is a critical metabolic step. ATP is almost always the phosphate donor, and the mechanism is remarkably consistent: the alcohol oxygen acts as a nucleophile, attacking the gamma-phosphorus of ATP and expelling ADP [

63]. It can be represented as A-P~P~P, where °~°°~° are the high-energy acid anhydride bonds. One of those is hydrolyzed. Breaking these bonds is an endergonic process that consumes energy rather than releasing it [

64,

65]. The negative change in the Gibbs free energy is due to the bonds formed after the hydrolysis process having a lower energy than before. The new bonds in hydrolysis allow the release of enormous energy, exactly 7.7 kcal/mol: ΔG= -7,7 kcal/mol o -31 KJ/mol [

66].

Unlike most biological processes in which only one phosphate group (

) is separated, the last two phosphate groups are released in the form of the pyrophosphate group (

) in replication. This process can be summarized in a chemical equation:

| |

[67]. |

Similarly, during transcription elongation, the overall reaction equation:

| |

[68] |

The H-bond is a robust fixed dipole-dipole electrostatic force when many molecules join. It provides excellent stability but is weaker than the covalent or ionic bonds. The energy of a H-bond is typically 5 to 30 kJ/mol, but it can vary from very weak to very strong. For N—H...N, it is approximately 13 kJ/mol. Intermolecular H-bond is responsible for the high boiling point of water (100°C). Hydrolysis of ATP to ADP and inorganic phosphate releases 30.5 kJ/mol of enthalpy, with a change in free energy of 3.4 kJ/mol [

66].

A transition between energy levels caused by forcing one of the system parameters’ Hamiltonian is called a Landau-Zener transition. A series of successive Landau-Zener transitions occur when a TLS is subject to periodic forcing on one of its parameters with a sufficiently intense amplitude [

69]. Detuning can be modified externally

where

and

are the forcing amplitude and frequency, respectively. The qubit levels are anti-symmetrically coupled

The qubit eigenstates can be defined as , .

The dispersive detuning regime, where

is helpful in quantum computing because it allows quantum measurements of the qubit state and its manipulation [

11]. Irradiating at the qubit frequency

can be used to manipulate the qubit coherently. When irradiating at the resonator frequency

, a sizable photon population is introduced in the cavity. The states of these photons become entangled with the qubit states. The law of conservation of linear momentum requires that at least two photons be created so that the resulting linear momentum can be equal to zero [

46,

70]. The photon is the gauge boson of the electromagnetic interaction and, therefore, is a boson that acts as a carrier of a fundamental interaction of nature. Conservation laws can determine the energies of the two photons or, equivalently, their frequencies. A driving radiation field of frequency

acting on the qubit-resonator system during a specific time can be described by the Hamiltonian [

71]:

where

q is the electron charge.

Every qubit corresponds to a point on the Bloch sphere, where the poles represent the eigenstates [

72]. The colatitude angle,

, runs through the angles from 0 to

, while the azimuthal angle,

, runs from 0 to 2

[

73]. The effect of a quantum gate on a single qubit is a rotation in the Bloch sphere, giving rise to a new qubit. In the Bloch sphere, we visualize the action of different logic gates or the temporal evolution of the state of a TLS described by a Hamiltonian. An axis and a rotation angle define a rotation operator [

74]. Its action produces a rotation of the point on the sphere concerning the rotation axis at the rotation angle [

73,

75]. The relationship between the angle of rotation in the x-axis and the pulse parameters in the Bloch sphere is represented in the equation:

Since the Rabi oscillations follow an expression of sin

2, we can obtain their period and determine the Rabi frequency and, even more importantly, the value of the variable parameter of the pulse makes it go from the state

to the state

, a logic gate

[

75]. To perform rotations around the y-axis, multiply the pulse amplitude by the imaginary unit (a phase of

that is added to the pulse).

For example, on the Bloch sphere, the Hadamard transformation is equivalent to a 90° rotation around the Y axis, followed by a 180° rotation around the X axis. It is also comparable to a 180° rotation about the Z axis followed by a 90° rotation about the Y axis.

By combining Equation 11 with the Hamiltonian of the system in Equation 9 and applying the unitary transformation [

52]:

We get the single qubit Hamiltonian in the frame rotating at the driving radiation field of frequency

acting on the qubit-resonator system during a specific time:

If a transient voltage is applied to the end of a transmission line, the line will draw a current proportional to the voltage’s magnitude divided by the line’s impedance (I = V/Z). This simple Ohm’s Law relationship between current and voltage will hold for a limited period [

76]. If the end of a transmission line is an open circuit, that is, left disconnected, the current “wave” propagating down the length of the line will have to stop at the end since electrons cannot flow where there is no continuous trajectory. Three effects can generate a superconducting phase difference around the circuit [

11].

1-Due to the Josephson effect. When the pairs coherently pass through a JJ, the supercurrent related to the phase difference between electrodes can be represented by . is the maximum critical current the junction can maintain. In our model of DNA, the maximum crucial current of the H-bond is .

2—Due to the supercurrent, an intrinsic phase shift appears when computing the line integral of momentum pairs moving along the curve.

3-Due to external magnetic flux. Classical electromagnetism and Maxwell’s laws show that a magnetic field that changes with time induces an electric field. This, in turn, modifies the momentum of the charged particles by exerting a force on them. The moment of the electron pairs is given by equation . The first component corresponds to the kinetic part, and the second to the field contribution—the potential vector is .

In our DNA model, RNA pol II changes the external magnetic flux through a phosphorylation mechanism and generates a phase difference. RNA pol II sends the system pair of pulses with the same parameters many times (n). The total number of pulses required may explain why the enzyme’s catalytic site has 52 repeats (

Figure 1A). Then, the number of times (m) the system was in state

or

is extracted. With these data, the probability that the system is in a specific state is calculated by applying Laplace’s rule. For example, to obtain the probability that it is in state

:

. We can obtain the Rabi oscillations by representing the probabilities as a function of times. At a computational level, a pulse is a finite time series of complex values, where each value represents a pulse amplitude at a given time. In DNA, a pulse is a finite time series of phosphorylation reactions.

Discussion

The states of spin 1/2 particles are TLS that can be used for quantum computation. (Petersson et al., 2012). In the DNA ground state, the

-ring controlled the hyperfine and electron-mediated nuclear spin interactions because the electron is sensitive to externally applied electric fields. Previously, close connections between classical and quantum information were described in DNA [

8]. In this work, we characterized A-T and C-G bp as flow qubits, as they constitute a superconducting ring interrupted by one JJ and crossed by a magnetic flux. Recent studies show that the H-bond between DNA bp can be treated as adiabatic systems with spin-orbit coupling. Hubač and Cols. extensively defined qubits formed by Majorana fermions in the H-bond and discussed the entangled states in the bp [

78]. The Hamiltonian obtained in this work for the DNA qubits differs from that of the transmon. However, in the limit when L tends to be infinite (omitting the term

in Equation 2), our Hamiltonian (

Figure 2B) tends to be the transmon Hamiltonian (

Figure 2A).

In DNA, each bp is connected to the adjacent by the sugar-phosphate backbone. This structure is similar to a transmission line with distributed parameters. Changes in the magnetic field by the RNA pol II during transcription could flip nuclear spins at resonance. An applied magnetic field breaks electrons’ twofold spin degeneracy. A pulse of microwaves slightly detuned from the resonant frequency, and the phase of the reflected signal enables the state of the qubit to be determined. One question emerged: What is the energy above the ground state that gets the lowest donor-excited state? This work considers high intracomplex phosphorylation activity manifested in processive phosphorylation of alcohol residues in RNA pol II using ATP as the phosphate donor as the RNA pol II driving force. Recent works on multisite phosphorylation networks have revealed a new level of signal processing complexity based on signaling routes encoded into disordered regions of proteins [

79]. PPi release during transcription is a signature step in each nt addition cycle [

68]. A DNA circuit can be represented as a symmetric and antisymmetric sin function:

and

. We proposed the graphic representation of the DNA strands’ deformation due to the H-bond break to form the Bloch sphere. The rotations of the qubit are carried out during transcription (

Figure 1B).

Custom adjustment of the coupling of each spin to its neighbors and the magnetic field enables different operations to be performed on each spin simultaneously. Finally, measurements are performed by transferring nuclear spin polarization to the electrons and determining the electron spin state by its effect on the electrons’ orbital wavefunction. Irreversible interactions between electron and nuclear spins must not occur as the computation proceeds: the electrons must be in a non-degenerate ground state throughout the computation [

11].

Quantum mechanical computation requires, in addition to single spin rotations, the two-qubit controlled rotation operation, which rotates the spin of a target qubit through a prescribed angle if, and only if, the control qubit is oriented in a specified direction and leaves the orientation of the control qubit unchanged [

20]. The measurable signal decreases with the number of qubits [

80]. Previous studies reported that scaling this approach above ten qubits will be technically demanding. Looking at the spins inside a DNA loop, they are arranged in parallel. In principle, logical operations and measurements can be performed independently and in parallel on each spin in the array.

Circuit QED is moving toward multiple superconducting qubits and three-dimensional cavities with greatly enhanced coherence time [

21]. Also, single-step multi-qubit phase gates on multiple single-mode resonators mediated by a bus of a multi-level superconducting atom in circuit QED have been described [

81]. The superconducting bus induces indirect interaction among multiple single-mode resonators, and quantum information is encoded in various single-mode resonators’ vacuum and single-photon states [

11]. Distributed quantum computation could be realized using numerous single-mode resonators [

20]. In addition, the pulse engineering technique can shape the coupling strength between resonators and the bus to enhance the scheme’s fidelity and robustness. Realizing the multi-qubit phase gate loosens the strict operation time without precise control. The tunable coupling strength plays a broad role in the circuit QED system [

20].

Based on the above information, we can establish that a DNA gene’s basic structure is the nonperturbative circuit QED, and a complete gene would be the linear combination of

number of circuits in parallel. This parallel arrangement, together with its superconducting nature, contributes to the total resistance being zero, and there is no heat dissipation. We consider DNA gene transcription a system consisting of

cavities, each hosting nine qubits and coupled to a shared machine. Many qubits in a single cavity may increase the unwanted qubit-qubit interaction and the cavity decay while decreasing the qubit-cavity coupling strength [

20,

54,

80]. Hence, cavity-based large-scale quantum information processing may involve multiple cavities and require applying quantum operations on qubits distributed in different cavities.

The RNA pol II bus interacts capacitively with

single-mode microwave resonators. It holds a level structure formed by ground and excited levels, denoted by

and

, respectively. Adjusting the qubit level spacings achieves the coupling and decoupling of each qubit from its cavity. The phosphorylation pulses applied to the bus drive the transitions resonantly between

and

with Rabi frequency

. Realizing quantum information transfer (QIT) and entanglement with SQUIDs in a microwave cavity is feasible in artificial atom models [

82].