Submitted:

13 September 2024

Posted:

16 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Quaternion Stochastic Filtering

2.1. Problem statement

2.2. Augmented stochastic process

2.3. Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman inequality

2.3.1. Case where

Summary:

2.3.2. Case where

2.4. Storage function V

2.5. Sufficient conditions on the matrices , ,

2.5.1. Convexity condition with respect to

2.5.2. Case where

Sufficient conditions in the form of Linear Matrix Inequalities:

2.5.3. Case where

Sufficient conditions in the form of LMI:

2.6. Quaternion stochastic filters summary

2.6.1. Case where

2.6.2. Case where

3. Quaternion and Gyro Drift Estimation

3.1. Statement of the problem

3.2. Design model development

4. Numerical Simulation

4.1. Description

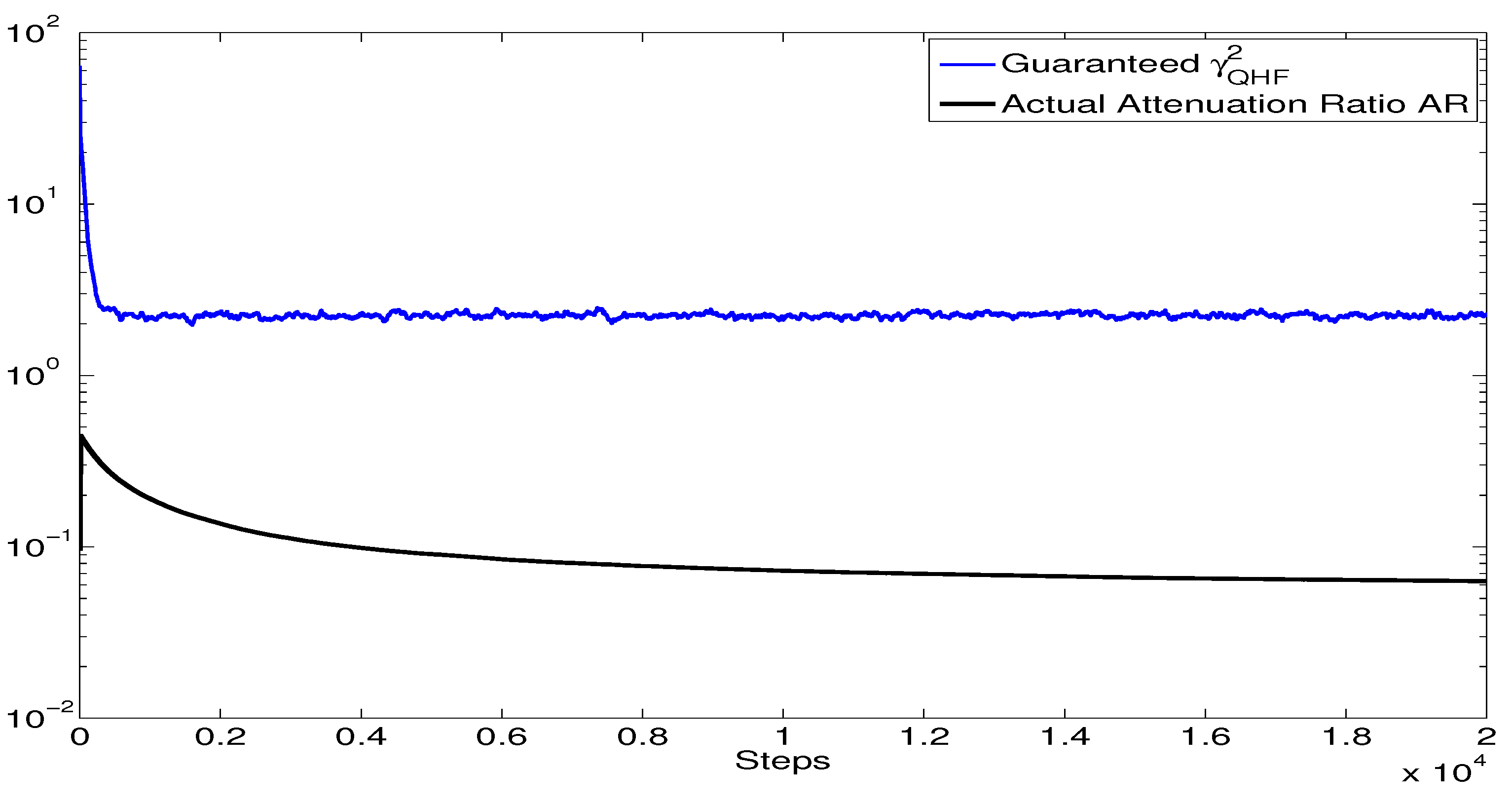

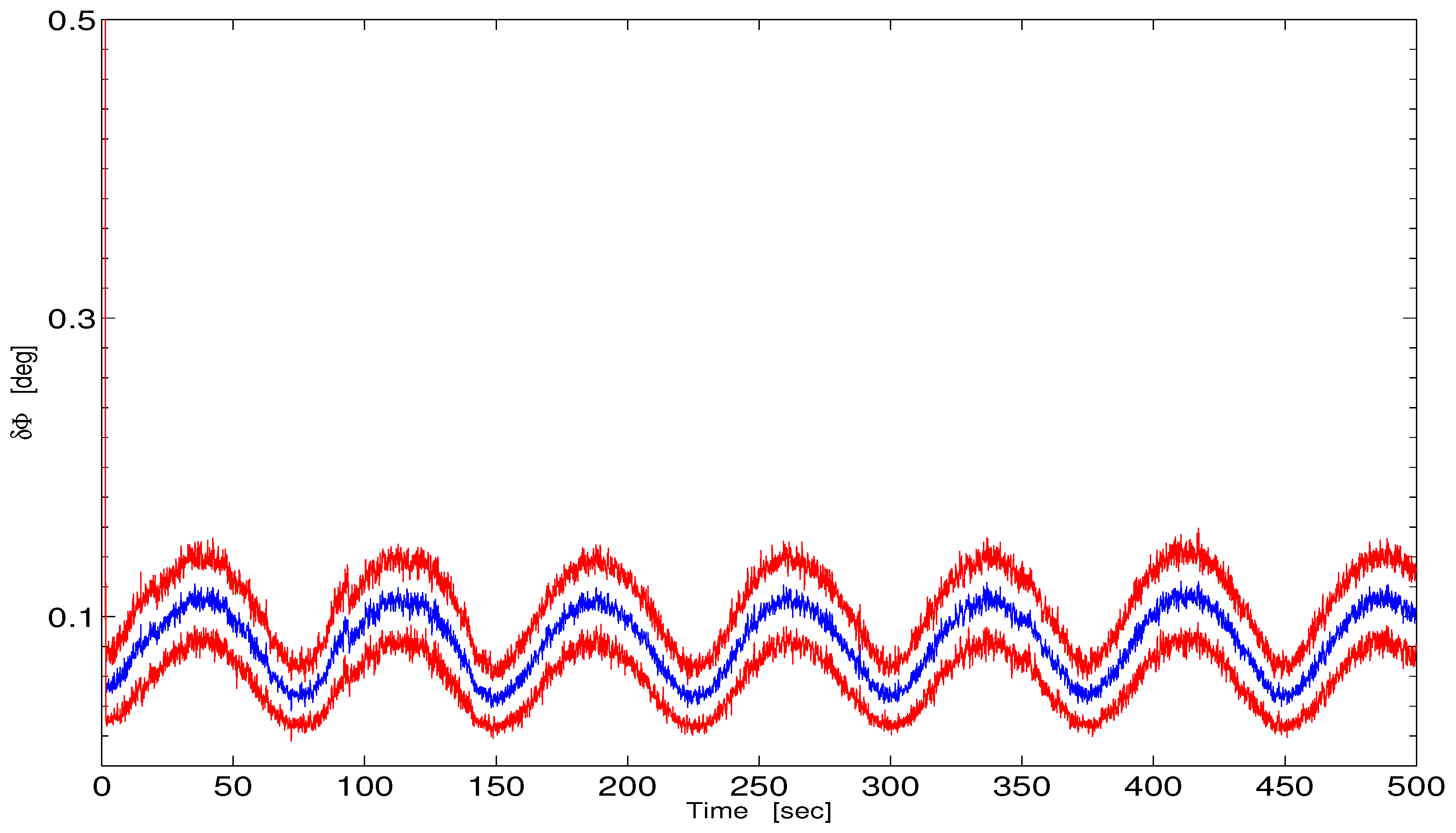

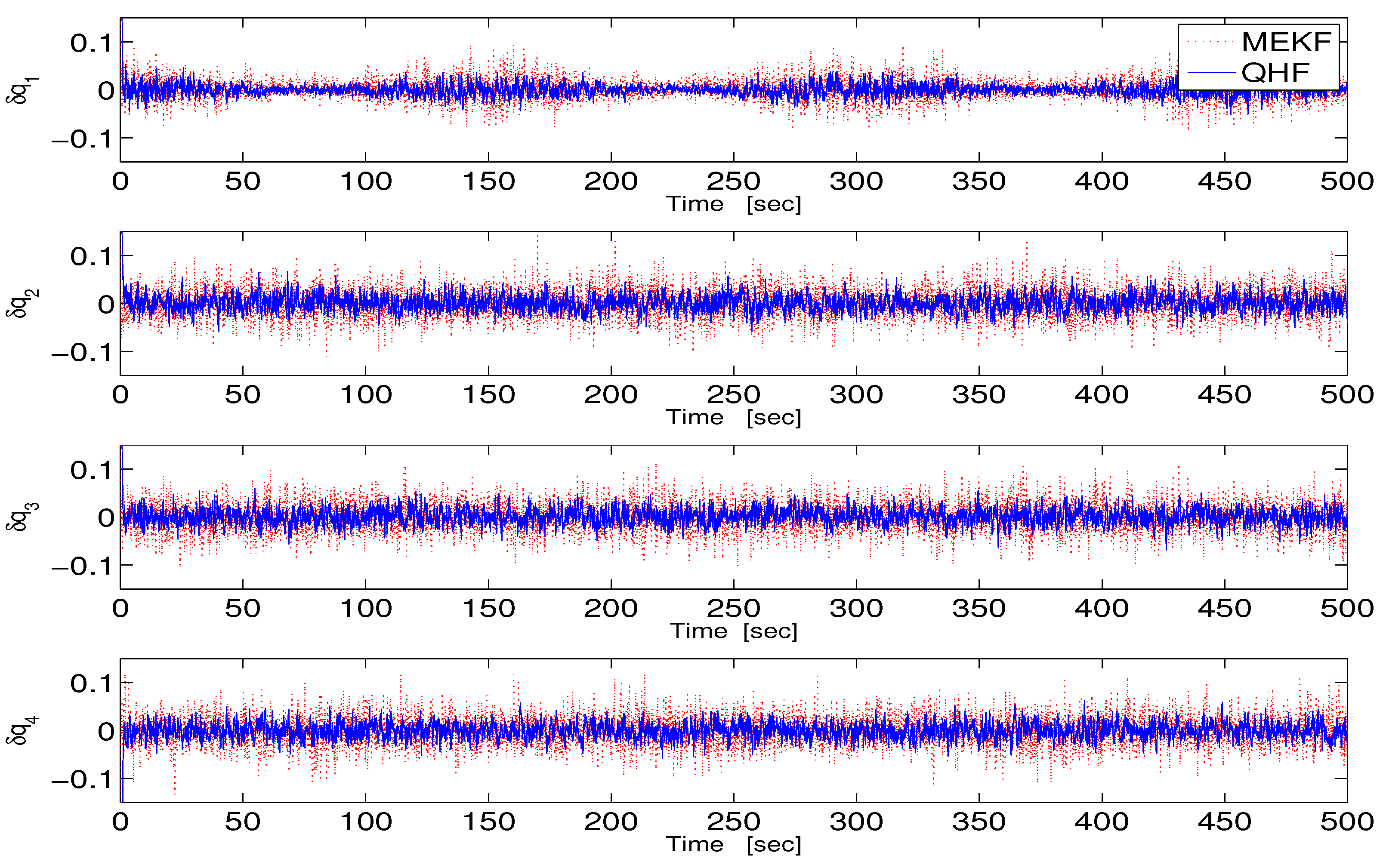

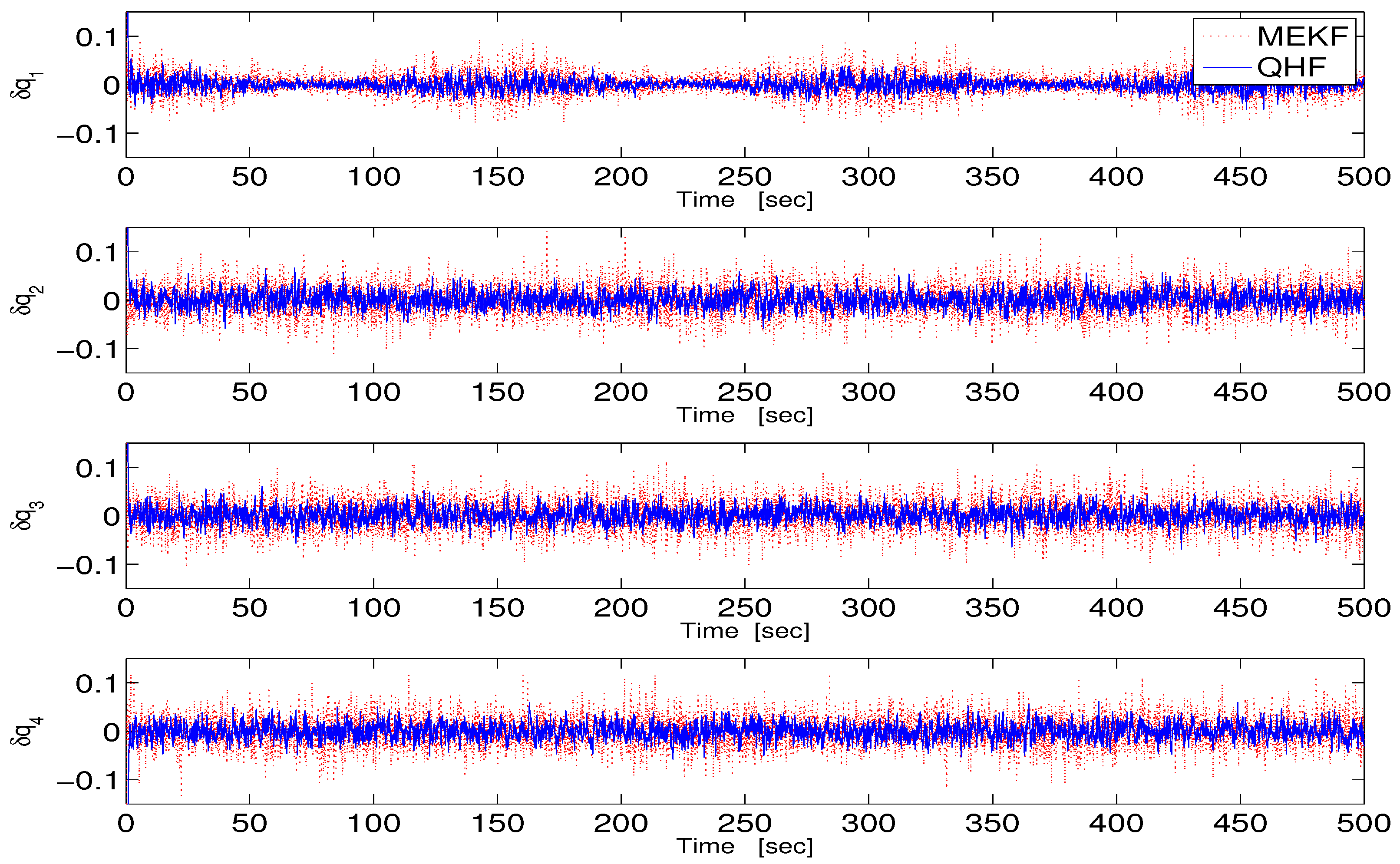

4.2. Attenuation of gyro

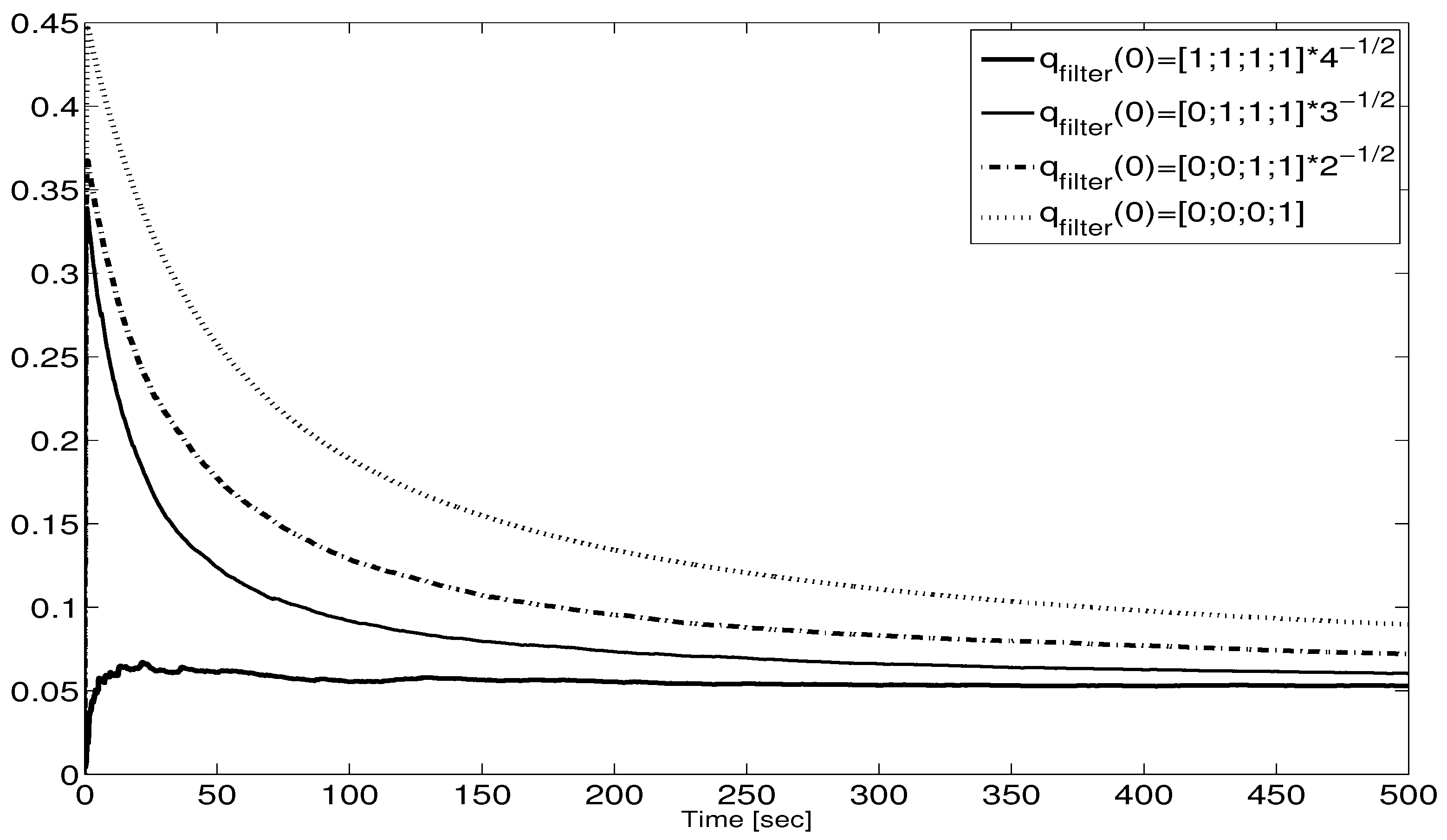

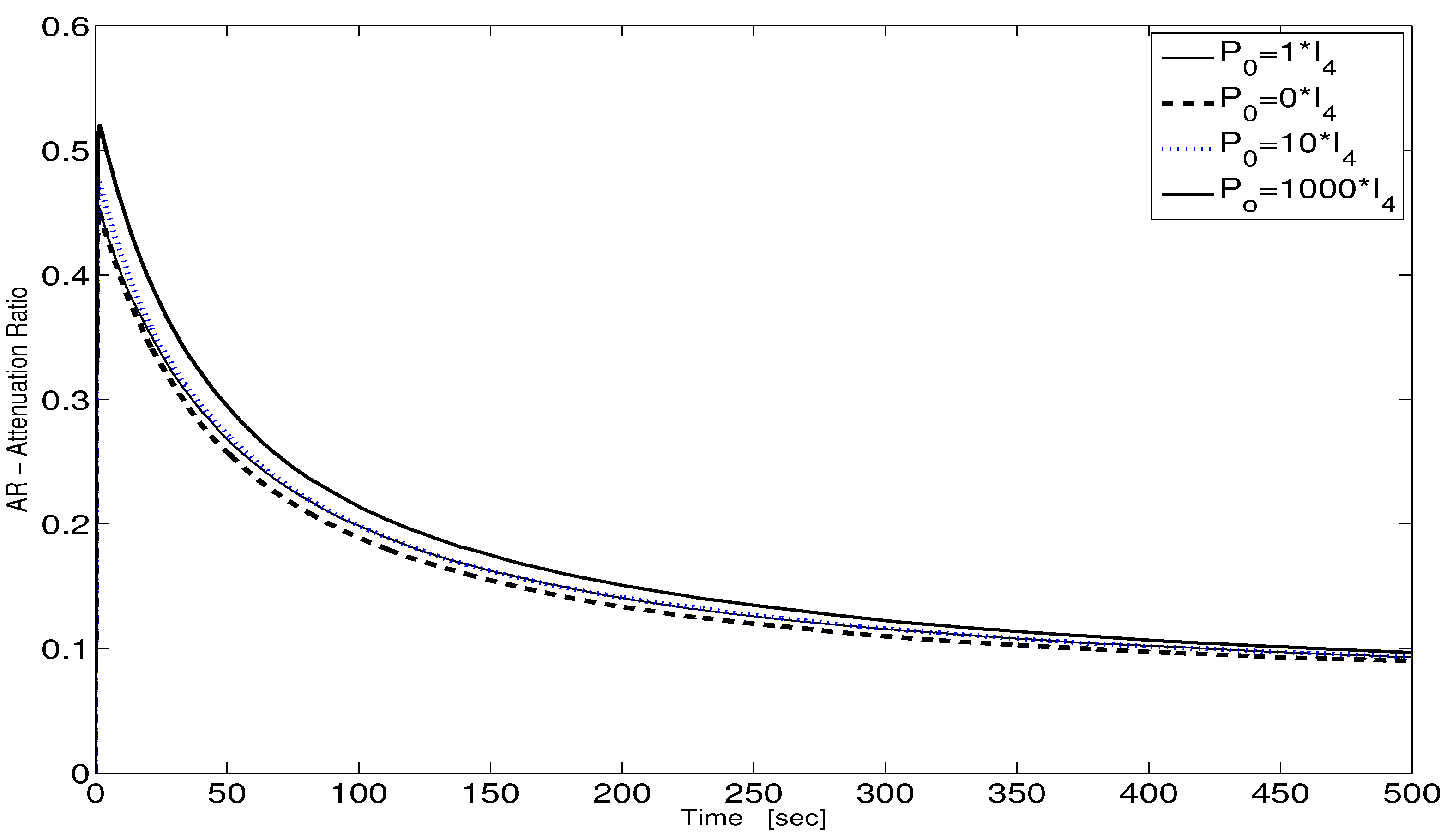

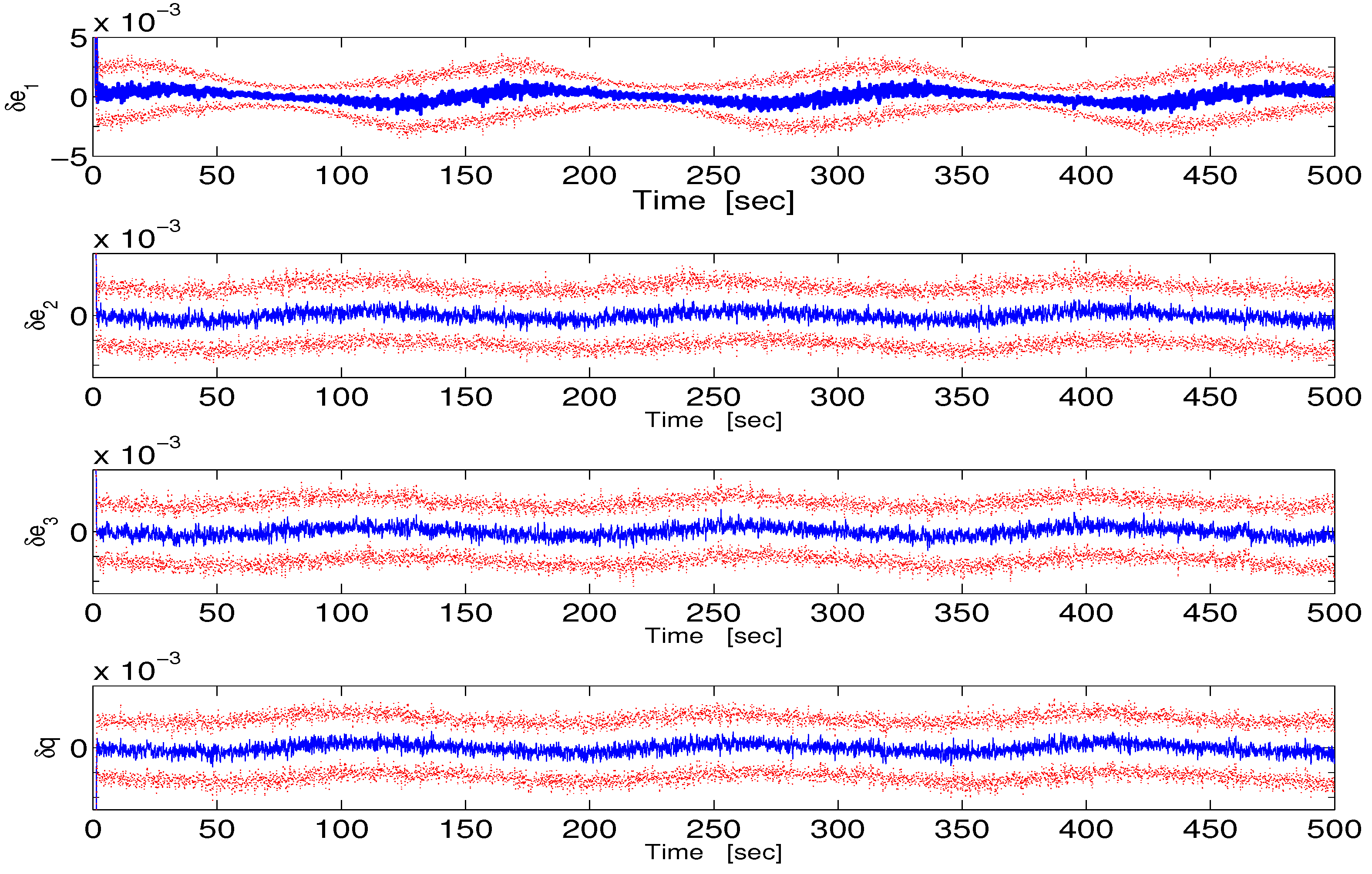

4.3. Attenuation of and

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wertz, J. R. (ed.), Spacecraft Attitude Determination and Control, D. Reidel, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1984.

- Crassidis, J., Markley, F. L., and Cheng, Y., Survey of Nonlinear Attitude Methods, Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics, 2007, Vol. 30, No. 1, pp. 12–28. [CrossRef]

- Lefferts, E. J., Markley, F. L., and Shuster, M. D., Kalman Filtering for Spacecraft Attitude Estimation, Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics, 1982, Vol. 5, No. 5, pp. 417–429. [CrossRef]

- Bar-Itzhack, I. Y., and Oshman, Y., Attitude Determination from Vector Observations: Quaternion Estimation, IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems, 1985, Vol. AES-21, No. 1, pp. 128–136. [CrossRef]

- Markley, F.L., Crassidis, J.L., Fundamentals of Spacecraft Attitude Determination and Control, Springer, 2014.

- Choukroun, D., Oshman, Y., and Bar-Itzhack, I. Y., Novel Quaternion Kalman Filter, IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems, 2006, Vol. 42, No. 1, pp. 174–190. [CrossRef]

- Thienel, J., and Sanner, R. M., A Coupled Nonlinear Spacecraft Attitude Controller and Observer with an Unknown Constant Gyro Bias and Gyro Noise, IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 2003, Vol. 48, No. 11, pp. 2011–2015. [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, R., and Bishop, R. H., Kalman Filters with Uncompensated Biases, Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics, 2012, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp. 327–335. [CrossRef]

- Markley, F. L., Berman, N., and Shaked, U., Deterministic EKF-like Estimator for Spacecraft Attitude Estimation, In Proceeding of American Control Conference, Baltimore, MD, IEEE Publ., Piscataway, NJ, 1994, pp. 247–251. [CrossRef]

- Silva, W., Kuga, H., and Zanardi, M., Application of the Extended H∞ Filter for Attitude Determination and Gyro Calibration, In Proceedings of AAS/AIAA Spaceflight Mechanics Meeting, Santa-Fe, NM, 2014; Advances in the Astronautical Sciences, 152; AAS 14-306.

- Silva, W., Garcia, R., Kuga, H., and Zanardi, M., Spacecraft Attitude Estimation using Unscented Kalman Filters, Regularized Particle Filter, and Extended H∞ Filter, In Proceedings of AAS/AIAA Spaceflight Mechanics Meeting, Snowbird, UT, 2018; Advances in the Astronautical Sciences, 162; AAS 17-673.

- Lavoie, M.-A. Arsenault J., and Forbes, J., R., An Invariant Extended H∞ Filter, In Proceedings of IEEE 58th Conference on Decision and Control, Nice, France, 2019, pp. 7905-7910. [CrossRef]

- Berman, N., and Shaked, U., H∞ Filtering for Nonlinear Stochastic Systems, In Proceedings of 13th Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation, Limassol, Cyprus, 2005; IEEE Publ., Piscataway, pp 749–754. [CrossRef]

- Berman, N., and Shaked, U., H∞-like Control for Nonlinear Stochastic Systems, Systems and Control Letters, 2006, Vol. 55, No. 3, pp. 247–257. [CrossRef]

- Choukroun, D., Novel Stochastic Modeling and Filtering of the Attitude Quaternion, The Journal of the Astronautical Sciences, 2009, Vol. 57, Nos. 1-2, pp. 167–189. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L., Choukroun, D., and Berman, N., Spacecraft Attitude Estimation via Stochastic H∞ Filtering, In Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance Navigation and Control Conference, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2010. AIAA 2010-8340. [CrossRef]

- Jazwinski, A.H., Stochastic Processes and Filtering Theory, Academic Press, New-York, 1970.

- Speyer, J.L., Chung, W.H., Stochastic Processes, Estimation, and Control, Advances in Design and Control, 17, SIAM, 2008.

- Sturm, J.F., Using SeDuMi 1.02, a MATLAB toolbox for optimization over symmetric cones, Optimization Methods and Software, 1999, vol. 11, Nos. 1-4, pp. 625–653. [CrossRef]

- Lofberg, J., YALMIP : a toolbox for modeling and optimization in MATLAB, In Proceedings of IEEE International Symposium on Computer Aided Control Systems Design, 2004; IEEE Publ., Piscataway, pp. 284-289. [CrossRef]

- Gershon, E., Shaked, U., Yaesh, I., H∞ Control and Estimation of State-multiplicative Linear Systems, LNCIS-Lecture Notes in Control and Information Sciences, Springer-Verlag, Vol. 318, 2005, Appendix C.

Short Biography of Authors

|

Daniel Choukroun received the B.Sc., M.Sc., and Ph.D. degrees in 1997, 2000, and 2003, respectively, from the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Faculty of Aerospace Engineering. He also received the title Engineer under Instruction from the Ecole Nationale de l’Aviation Civile, France, in 1994. From 2003 to 2006, he was a postdoctoral fellow and a lecturer at the University of California at Los Angeles in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering. Since 2006, he has been with the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel, where he is currently a Senior Lecturer. Between 2010 and 2014 during a leave of absence, he was Assistant Professor in Space Systems Engineering with the Aerospace Engineering Faculty of the Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands. Dr. Choukroun is member of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control technical committee, the CEAS GN&C technical committee, and the EUCASS FD&GNC technical committee. He is Review Editor for Frontiers in Aerospace Engineering. He was Associate Editor of the IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems and of the CEAS Space Journal. |

|

Lotan Cooper received his B.Sc. and M.Sc. degrees in mechanical engineering from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in 2008 and 2010 respectively. Between 2010 and 2017 he worked at HP Indigo LTD. as a Control and Algorithm Engineer as part of the research and Development section, specializing in developing control schemes and sequences for large digital press machines and their accompanying robotics, and, later, as a system engineer as part of the Media Handling systems development group where he mainly developed sub-systems for sensing, gripping and alignment of special media types. In 2017 he received the title of Flight Control engineer when working at Pozidrone, Aeronautics LTD, specialising in multi-rotor UAVs. From 2021 to 2022 he worked as a flight control engineer at Pentadrone LTD, where he specialized in fixed-wing and Vertical-Takeoff-Landing (VTOL) UAVs. He is currently with the Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) working as a guidance and control engineer in - Systems Missiles & Space Division. |

|

Nadav Berman received the B.Sc. and M.Sc. degrees in aeronautical engineering from the Technion - Israel Institute of Technology in 1971 and 1974, respectively, and the Ph.D. degree in 1980 from the Department of Computer Information and Control Engineering at the University of Michigan. From 1978 to 1981 he was a research scientist in the radar division of the Environmental Research Institute of Michigan (ERIM), and from 1981 to 1982 he was a member of the technical staff at Bell Laboratories in New Jersey, United States. In 1982 he joined the Department of Aeronautical Engineering at the Technion. He moved to the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Ben-Gurion University in 1988, from which he retired in 2011 as a full professor. During his sabbatical years, Nadav was a research scientist at the Computer Science Corporation in Maryland, United States, in 1988 and a senior research resident at the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, in 1992. One of his influential publications, which was in collaboration with the late Prof. Itzhack Y. Bar-Itzhack, was on a control theoretic approach to the analysis of inertial navigation systems. Much of Prof. Berman’s interests in the last 20 years were in the theory of estimation and control of nonlinear systems. In collaboration with Prof. Uri Shaked, he developed a dissipativity-based theory for stochastic nonlinear systems that applies to filtering, parameter estimation, and control design. |

| 0 | ||||||

| 0 | ||||||

| MEKF QHF | MEKF QHF | MEKF QHF | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).