1. Introduction

Closed loop vertical ground source heat pumps are notably widespread for their efficiency and effectiveness compared to other ground source heat pump types like horizontal closed loop, direct exchange, open loop, and surface water ground source heat pumps [

1]. One of their key advantages is the compact footprint of the heat exchanger in the form of a borehole, which makes them especially suitable for residential areas with small plots and commercial buildings [

1]. They also ensure stable ground temperature and demand minimal pumping energy [

1]. However, the system does have drawback of requirement for a deep borehole drilling which contributes to a higher cost and challenges related to expertise in borehole drilling and proper implementation [1, 2].

Typically, water (or a mixture of water and antifreeze in below-freezing soil conditions) circulates on one side of the ground source heat exchange system, while refrigerant circulates on the other side, directly connected to the heat pump. According to ASHRAE-Applications [

3], U-tube boreholes typically range from 100-150 mm in diameter and have depths of 15-120 m. U-tube borehole length can be further increased to 180 m or more if the procedures for deep boreholes are followed. A U-tube containing the circulating fluid is inserted into each borehole, typically made of polyethylene with a diameter of 20-40 mm, although other pipe materials may also be utilized [

3].

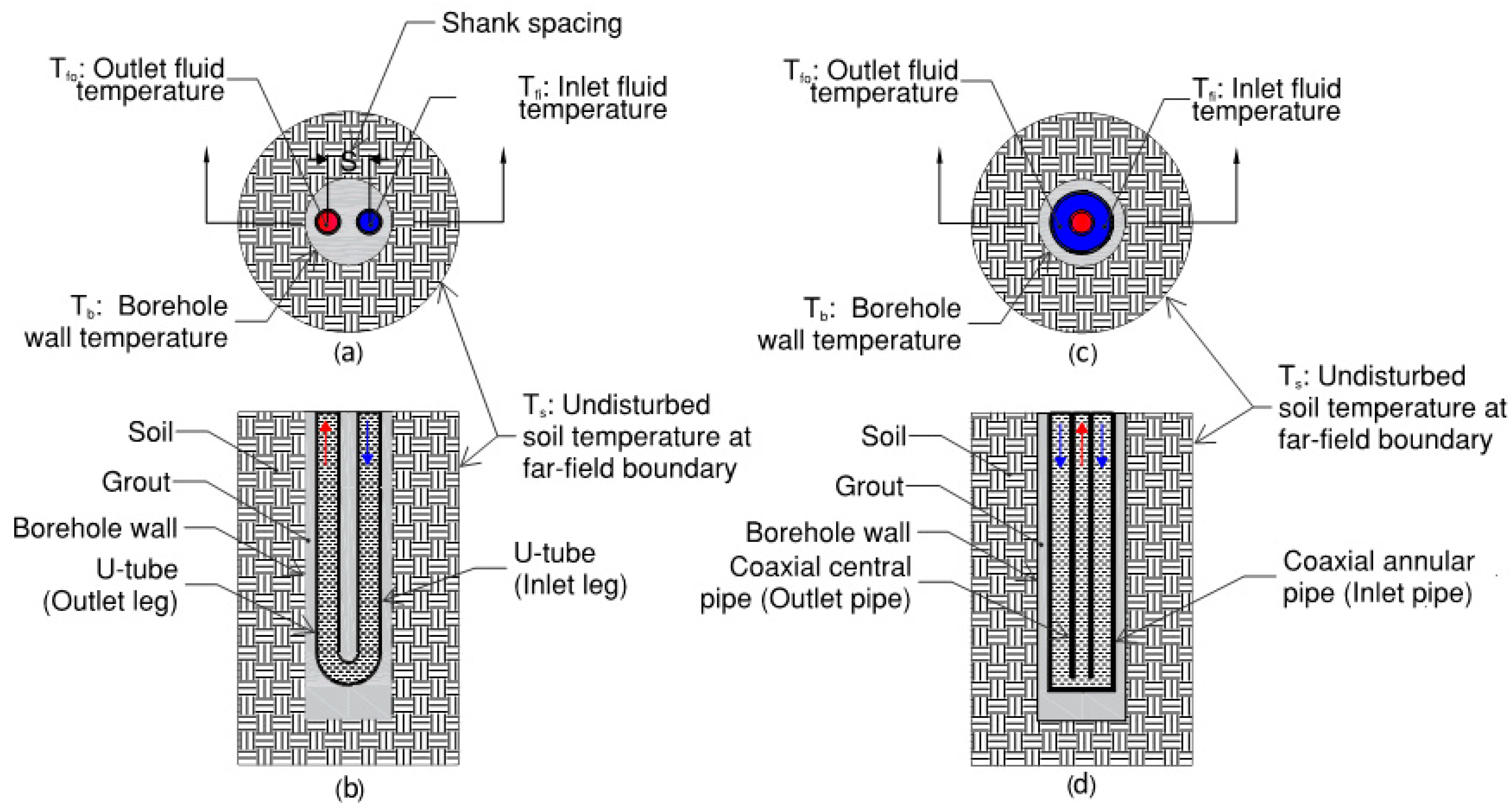

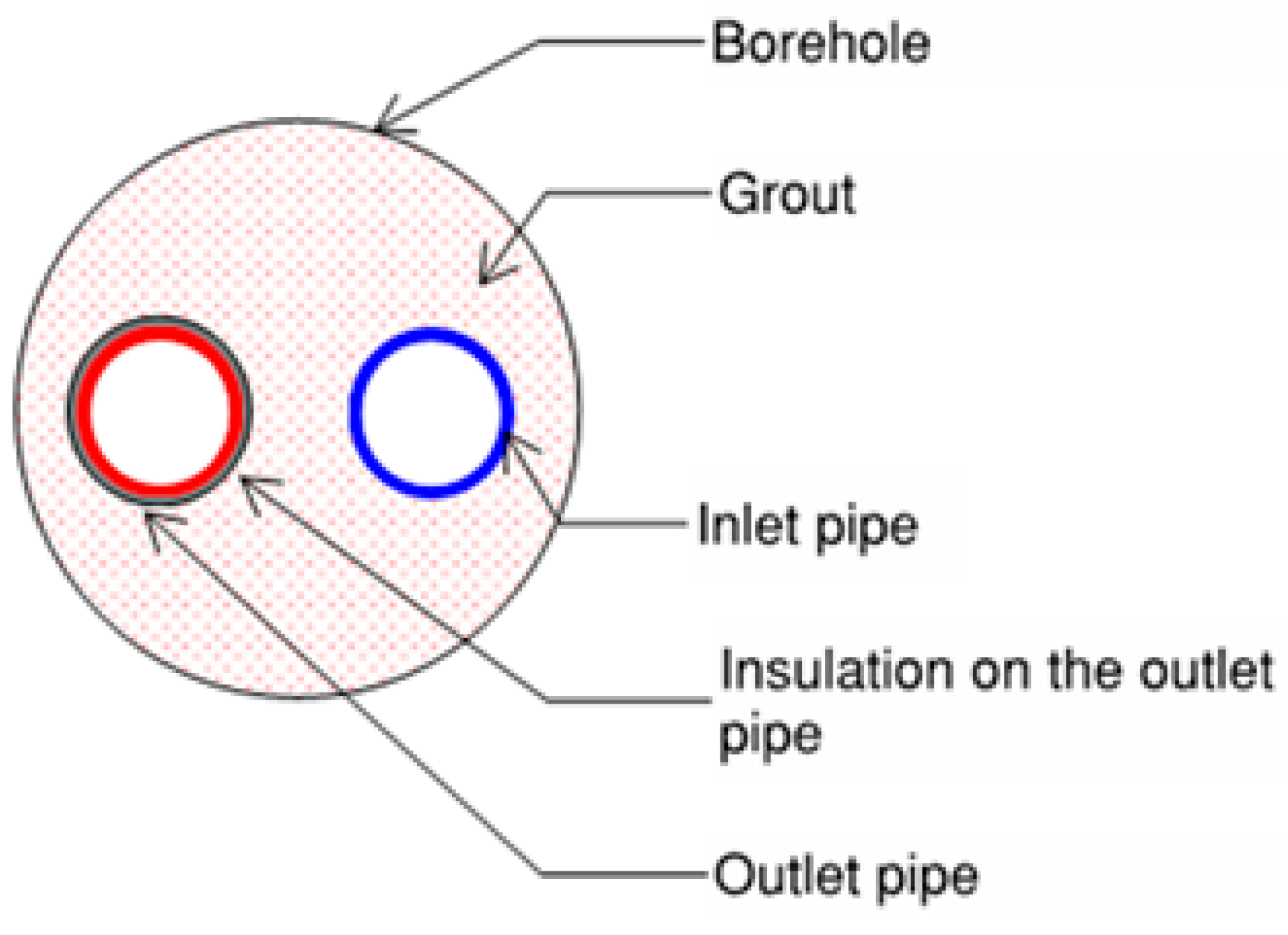

Figure 1(a) and

Figure 1(b) illustrate the U-pipe arrangement.

An alternative to U-tube boreholes is coaxial pipe arrangement where a smaller pipe (the inner pipe) is enclosed within a larger outer pipe. The heat transfer fluid can be circulated in two ways. One way is to enter the fluid through the outer pipe (inlet pipe) and return the fluid via inner pipe (outlet pipe). The other flow arrangement is to enter the fluid via inner pipe (inlet pipe) and return the fluid via outer pipe (outlet pipe).

Figure 1(c) and

Figure 1 (d) illustrate the coaxial pipe arrangement with inflow through the annular pipe.

Usually the space between the U-tube/ coaxial pipe and the borehole wall is filled with grout, which serves a crucial role in stabilizing the U-tube/ coaxial pipe within the buried system and in preventing water seepage into the borehole. BHX cost (which is mainly the cost of U-pipe, grout and borehole drilling) for GSHP typically accounts for more than 30% of the total cost of the GSHP system [

4] Given its significant expense, optimizing this component is vital for enhancing heat transfer efficiency and for harnessing more sustainable energy from the same area of the land.

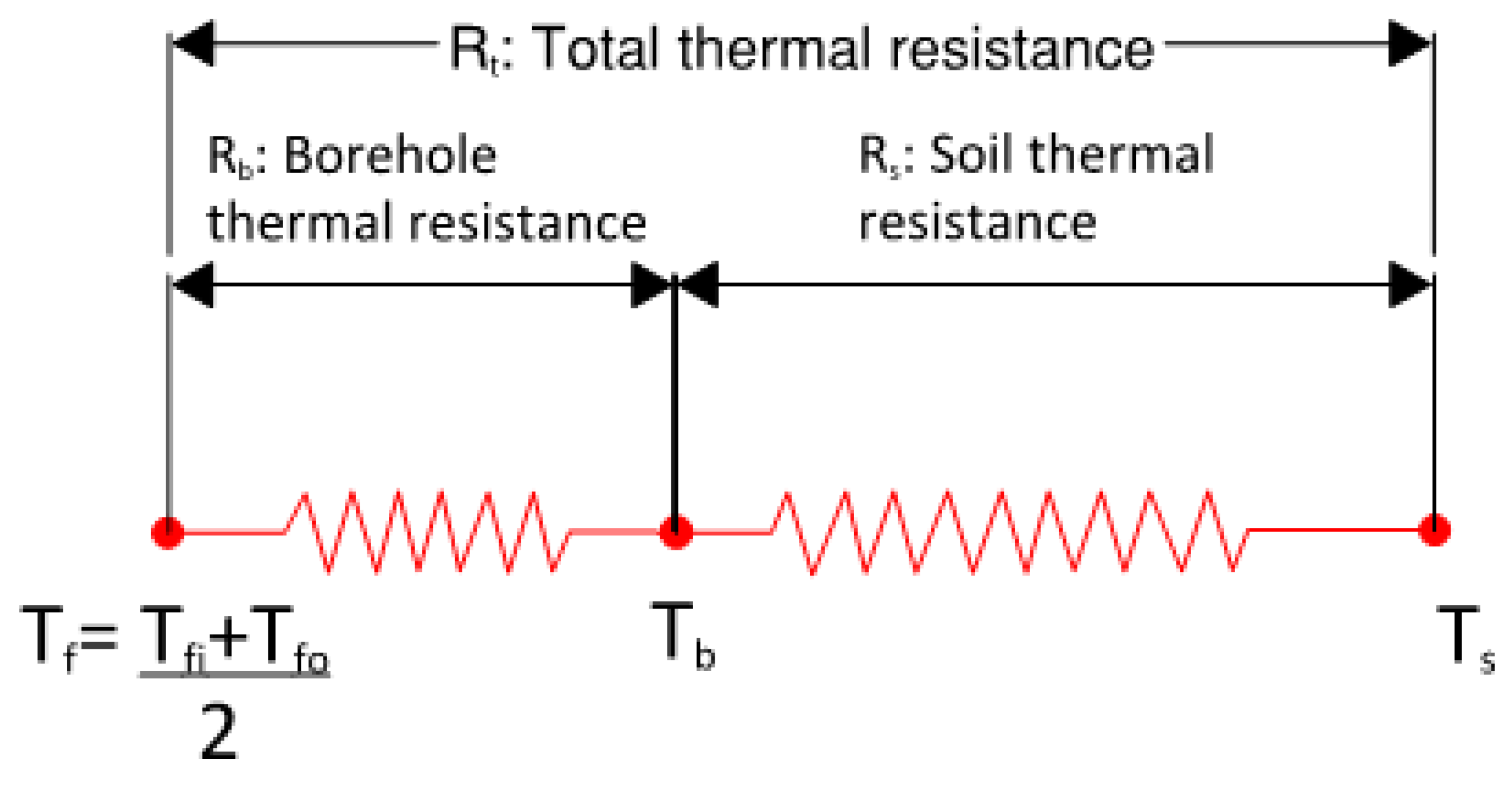

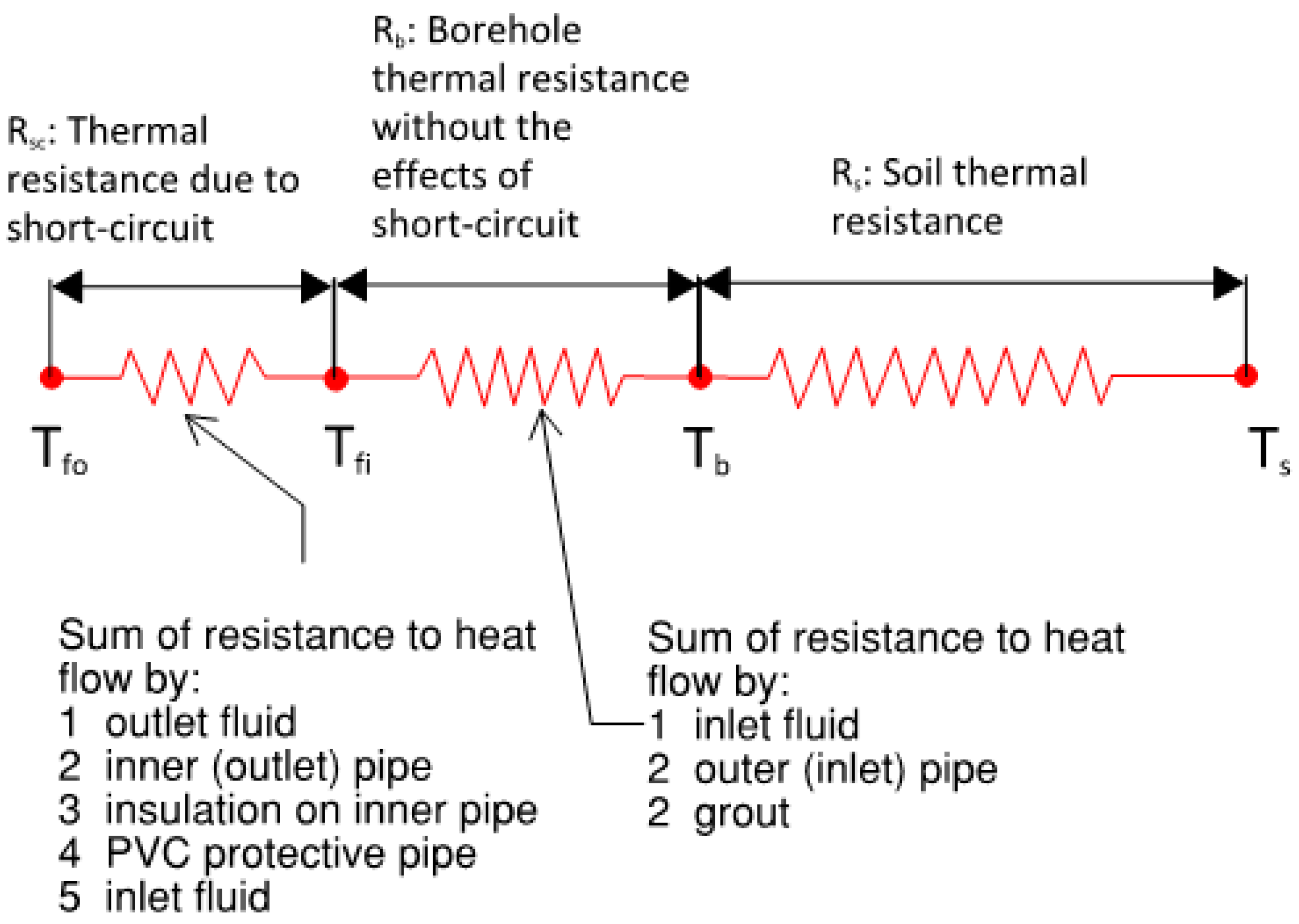

The total thermal resistance consists of two parts: the soil itself and the borehole as shown in

Figure 2. In a conventional U-tube BHX having a geometrical symmetry of the inlet and outlet legs, the fluid temperature to be considered for the evaluation of borehole thermal resistance is the mean temperature of the inlet and outlet fluid temperatures [

5].

The borehole resistance component includes the resistance offered by grout, pipe material, and the circulating fluid. Contact thermal resistance is assumed to be negligible for simplification. The total thermal resistance is the sum of soil and borehole resistance.

Reduction in any of the above two components or both will lead to an improved heat transfer. The heat transfer resistance characteristics of soil vary with geographic location and are generally immutable. Deep soil mixing offers a viable method to lower soil thermal resistance, yet its implementation is expensive and may not be economically feasible across all site conditions and soil types [

6]. On the other hand, there are methods to decrease Rb i.e. BHX thermal resistance. Therefore, the overall thermal resistance of the system can be reduced for an enhanced heat transfer by adopting techniques to lower the BHX thermal resistance.

Increasing the length of the ground loop in a BHX reduces the approach of BHX defined as the difference between average loop temperature T

f and the initial ground temperature T

s.

Reducing the thermal resistance between the ground and the circulating fluid enhances the heat transfer, thereby reducing the required length of the heat exchanger per kW for a given approach.

Previous research on the optimization of borehole thermal resistance has investigated the impact of pipe material, borehole diameter, shank spacing, and grout material. Research by Kerme et al. [

7] discusses various geometric factors (shank spacing, borehole size/diameter, borehole depth), grout and soil thermal conductivity for single and double U tube arrangements and then proposes the combined effective measures for heat transfer improvement. Shen et al. [

8] discusses the various influential factors (such as flow rate, inlet temperature, heat extraction rate, length of BHX and backfill material) on the performance of deep U-tube BHX and suggest an optimal control of flow rate.

According to Kavanaugh and Rafferty [

2] the choice of thermally enhanced grout material is also challenging. The grout filler must block surface water and unwanted groundwater from reaching aquifers, as they can pollute drinking or irrigation supplies. High-solids sodium bentonite grout (>20% solids), while effective, is a poor heat conductor, whereas materials with good heat transfer may allow water migration. Some regulations may permit porous materials if the top 6 meters of the borehole are sealed with a nonporous grout. Cement-based sealants are ineffective for BHX due to pipe shrinkage but can be enhanced with additives. Pouring of thermally enhanced grout with abrasive sand might also be challenging due to unavailability of the pumping equipment with the installer.

Erol and François [

9] studied various BHE grout materials, including bentonite-based, silica sand-based, and homemade admixtures with graphite. Increasing graphite content beyond 5% or using all types of graphite powders in BHE backfill mixtures is impractical, as graphite's varying properties can negatively affect grout flowability, permeability, and strength. By TRT test, they found that adding just 5% homemade natural flakes graphite enhances grout thermal conductivity, crucial for optimizing heat transfer efficiency when matched appropriately to ground conductivity.

Study by Mahmoud et al. [

10] suggests that selecting the right grout depends on system conditions. Traditional grouts like bentonite and cement offer strength but require additives for better thermal performance. Phase change material (PCM) is recommended for its storage capacity and stability. A mix of conventional grouts, additives, and PCMs is recommended for optimal results.

Liu et al. [

11] conducted a comprehensive study to assess potential cost reductions through enhancements in borehole heat transfer under diverse geological and thermal conditions and revealed that improvements such as enhanced grout and double U-tube loops effectively reduce borehole lengths. The study primarily focuses on installation costs and relies on the simplified geometrical approach of Eskilson’s g-function through commercial software.

Research work is also available on comparison of U-tube with coaxial pipe and a few other arrangements like double U-tube, discussing the thermal behavior of the BHX with these arrangements. Study made by Zanchini et al. [

12] showed that in coaxial pipes, the configuration where water flows into the BHX through the outer annular pipe and exits through the inner pipe provides superior thermal performance compared to the opposite arrangement, where inflow occurs through the center or inner pipe and outflow through the outer annular portion. Brown et al. [

13] modelled coaxial, single U-pipe and double U-pipe configurations, finding coaxial pipes exhibiting highest heat transfer rate and lower pressure drop. Harris et al. [

14] demonstrated that the coaxial BHX configuration is more effective than the double U-pipe design. According to Chen et al. [

15], by using double U-tubes in parallel in BHXs, the heat transfer capacity may increase by over 50% from the single U tube system which could justify the cost increase in installation and pumping energy consumption. Chen and Tomac [

16] suggest use of VIT (Vacuum Insulated Tube) for coaxial pipe arrangement to prevent thermal short-circuiting. An economic analysis is suggested as the cost of VIT is 5 times more than the cost of un-insulated tubing.

While there is an ample research work available on the comparative study of materials and geometry of the U-tube BHX and its comparison with the other arrangements like coaxial pipes and double U-tube, there is not much research work on segregating the inlet and outlet leg of the U-tube to prevent them from a direct interaction with each other.

Al-Chalabi [

6] investigated the effects of introducing I-shape and U-shape obstructions in a U-tube BHX. However, the study did not account for the thickness of the U-tubes, which led to extremely overestimated efficiency of the barriers compared to scenarios where tube thickness is considered. In addition, the study is limited to the highly thermally conductive grout with a ratio k

g/k

s of 2, and does not provide an insight into the various alternatives of the grout and soil. The results are reported in terms of the borehole thermal resistance instead of an overall thermal resistance. High thermal conductivity grout results in a lower contribution of the BHX thermal resistance out of the total thermal resistance of the soil and BHX. Therefore, there is a need to report the net impact of the saving in terms of an overall reduction in the total thermal resistance or borehole length or an overall increase in the heat transfer.

Ngo and Ngo [

17] conducted a numerical assessment to evaluate the impact of an insulated flat shape barrier between the U-tube legs of ground heat exchanger. The study examines the effects of Reynolds number on heat transfer, focusing on laminar flow with a low Reynolds number value (optimal heat transfer at Reynolds number of 120 and suggests that at lower Reynolds number values, heat transfer increases due to a decrease in the outlet temperature (T

fo) for a given inlet temperature (T

fi), though it does not address the impact of reduced mass flow rate on the heat transfer as a result of lower Reynolds number value. The heat rejected by the fluid for cooling will be as follows [

2]:

The expression for Reynolds number is as follows [

18].

The above equation depicts that the mass flow rate of the fluid is a function of Reynolds number. Under the given geometry and fluid temperature, the Reynolds number varies directly proportional to the mass flow rate of the fluid, which means the more the mass flow rate, the more will be the Reynolds number for a given geometry and fluid temperature. In case of turbulent flow through pipes, the Reynolds number is ≥ 10,000 [

18]. Ngo study with Reynolds number of 120 will have a significantly lower flowrate through the same geometry than the flow conditions considered in other studies with turbulent flow. The study does not very clearly state the pipe material considered in the study, however mentions that their study reports high efficiency operation with 16% enhanced heat transfer when copper pipe is used instead of high-density polyethylene. It is therefore understood that they have conducted a study based on copper pipes. Previous studies suggest that use of HDPE pipes is very common due to better performance, durability and economics [2, 19-21]. The assumption of copper piping with laminar flow within the U-tube could increase the risk of thermal short-circuiting than that with high density polyethylene pipe [

2]. Due to more short-circuiting, the results of improved heat transfer due to barrier between the inlet & outlet pipe will be misleading. Thickness of the pipe is also neglected which will overestimate the performance of the barrier. Because the study is not based on optimal parameters, there is a potential to increase the heat transfer further by improving the flow rate and pipe material. Measures to improve these parameters will result in a change in the reported impact of the barriers in the study, which warrants further analysis to draw definitive conclusions.

Previous studies about grout material have suggested that grout selection for better thermal conductivity might be challenging and may be compromised for the strength of the BHX and/or economy. The study of the novel technique of barriers between the two legs of BHX for optimization of heat transfer is required to be explored as an alternative to conventional way of increasing the heat transfer by thermally enhanced grout. The technique can also be applied in addition to the conventional methods to further increase the heat transfer. There is a need for a detailed evaluation of the thermal performance of the barrier between the two legs of a U-tube BHX, with a specific comparison to a conventional U-tube system. Due to complexity of the BHX geometry, numerical assessment would be more appropriate. Flat plate and U-shape geometries of the barrier are to be studied with various materials and thickness. The design parameters of BHX geometry and flow are to be optimized before evaluating the effect of barrier. Comparison to be made with a focus to depict the sole contribution of barrier from the base case. It is also required to report the results of an overall impact in terms of net increase in heat transfer or net reduction in the BHX length. This would allow for a clearer assessment of the barrier's unique contribution in optimizing the BHX length and will help implementing the barrier technique where they contribute to the enhancement of heat transfer through the BHX. Additionally, it would be beneficial to compare the results of numerical assessment for barrier techniques with other heat transfer enhancement techniques, such as coaxial pipe arrangements, to offer a broader selection of borehole heat exchanger (BHX) design options.

2. Methods

A traditional single U-tube heat exchanger was numerically assessed and validated for different combinations of shank spacing and grouts. A coaxial pipe BHX was also assessed to see the improvements in efficiency of the heat transfer in the BHX with coaxial pipe arrangement compared to a traditional single U-tube BHX. Next investigation was to see the effects of novel techniques of different barriers/ obstructions between the two legs of a U-tube BHX and comparison of the resulting improvement. Numerical assessment was done on FlexPDE software version 6.51, a finite element model builder and solver. The undisturbed soil temperature (Ts) and fluid temperature (Tf) remained constant across all options, leading to an unchanged Approach temperature, as determined by Equation 3. This study aimed to determine which borehole heat exchanger option minimized heat transfer resistance, thereby requiring the shortest length per kWt under these conditions.

2.1. Model Assumptions and Governing Equation:

The analysis was performed for a single BHX under steady-state heat transfer. The heat transfer inside the borehole for longer time steps can be considered as steady-state heat transfer within that time step [

22]. The lower limit of the time step is 5 times r

b2/α, which is usually a few hours for different soils and borehole sizes [5, 22]. Similarly, a radial steady-state approximation for the small annulus of the soil near the borehole gives an error of less than 0.3% in determining the resistance of the soil outside the borehole [

22]. Thus, for a time efficient model, we conclude that it is appropriate to consider steady-state heat transfer both inside and outside the borehole.

Homogeneous ground condition is considered in the analysis as a simplification assumption [

5]. With the assumptions of steady-state heat flow and homogenous ground material, a two-dimensional model can effectively capture the essential heat flow characteristics in the material and is therefore considered for the analysis.

A far-field radius is the radius of influence and beyond it, the temperature of the soil remains un-disturbed [

23]. According to the study made by Ruan, the soil within 0.5 meters of the borehole reacts to the short-term heat flux from the ground to the fluid. In contrast, the area beyond 0.5 meters is primarily influenced by the long-term net energy input into the ground heat exchange system. After 1 meter from the center of the borehole, there is no significant change in the mean fluid temperature [

24]. We therefore based our analysis for a far-field radius of 1 meter.

No contact resistance, no moisture migration through the soil, homogenous grout & pipe materials, water as a fluid and winter heating mode are considered in the analysis.

Fourier’s law of heat conduction is as follows [

25].

The transient heat transfer equation in three dimensional cartesian coordinate system is as follows [

25].

The steady state two-dimensional equation in cartesian coordinates reduces to the following expression which shall be the governing equation in this study which is expressed as follows [

25].

2.2. Analysis for Traditional Single U-Tube Borehole Heat Exchanger:

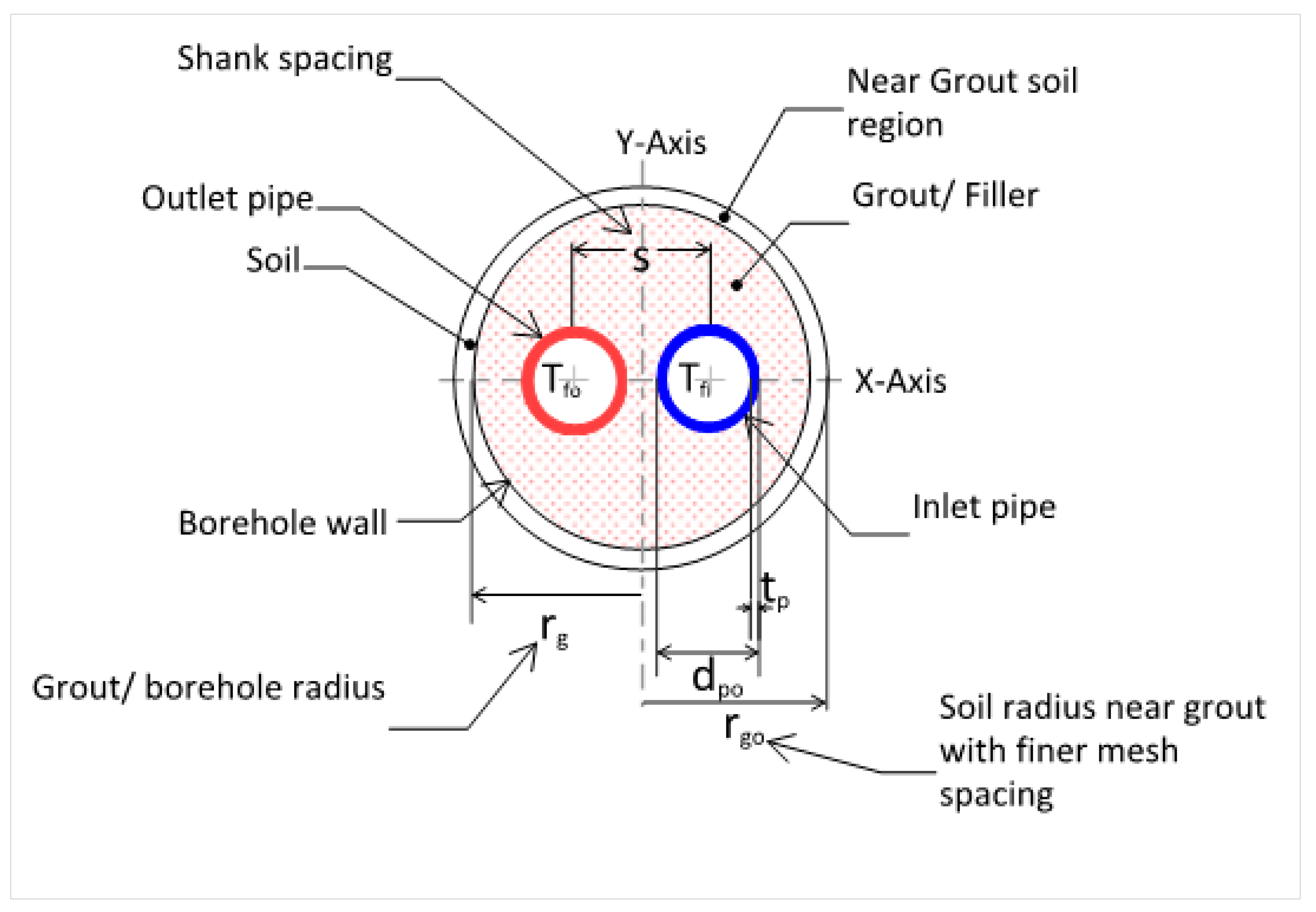

Figure 3 describes the geometry of the U-tube model. Far-field boundary is not shown here to represent an enlarged view of the borehole for clarity. Refer to

Figure 1 to see the far-field boundary.

The size and material of U tube and borehole diameter are in accordance with the recommendations in ASHRAE-Applications [

3]. Heating mode for winter operation of the GSHP is considered. For a better efficiency, the outlet temperature of the fluid in heating mode should be 5°C to 8°C less than the undisturbed ground temperature. [

2]. ΔT of 4°C to 3°C is adopted for water as a fluid to keep the cost and pumping energy within reasonable limits [

2]. The soil temperature taken is an approximation used to represent a range of Australian soils where the average geothermal ground temperatures are from 14⁰C to 18⁰C [26-28]. Soil thermal conductivity of 0.5 to 2 W/m.K also represents various soil conditions in Victoria, Australian Capital Territory and the near-by areas of New South whales [29, 30]. The grout materials are considered to represent a variety of grouts with or without a filler material to enhance their thermal conductivity. Neat cement grout with water-to-cement ratio of 0.6 has a thermal conductivity of 0.585 W/m.K after drying, whereas grouts with thermal conductivity of 1 & 2 W/m.K represent thermally enhanced cement grouts with a combination of filler materials [

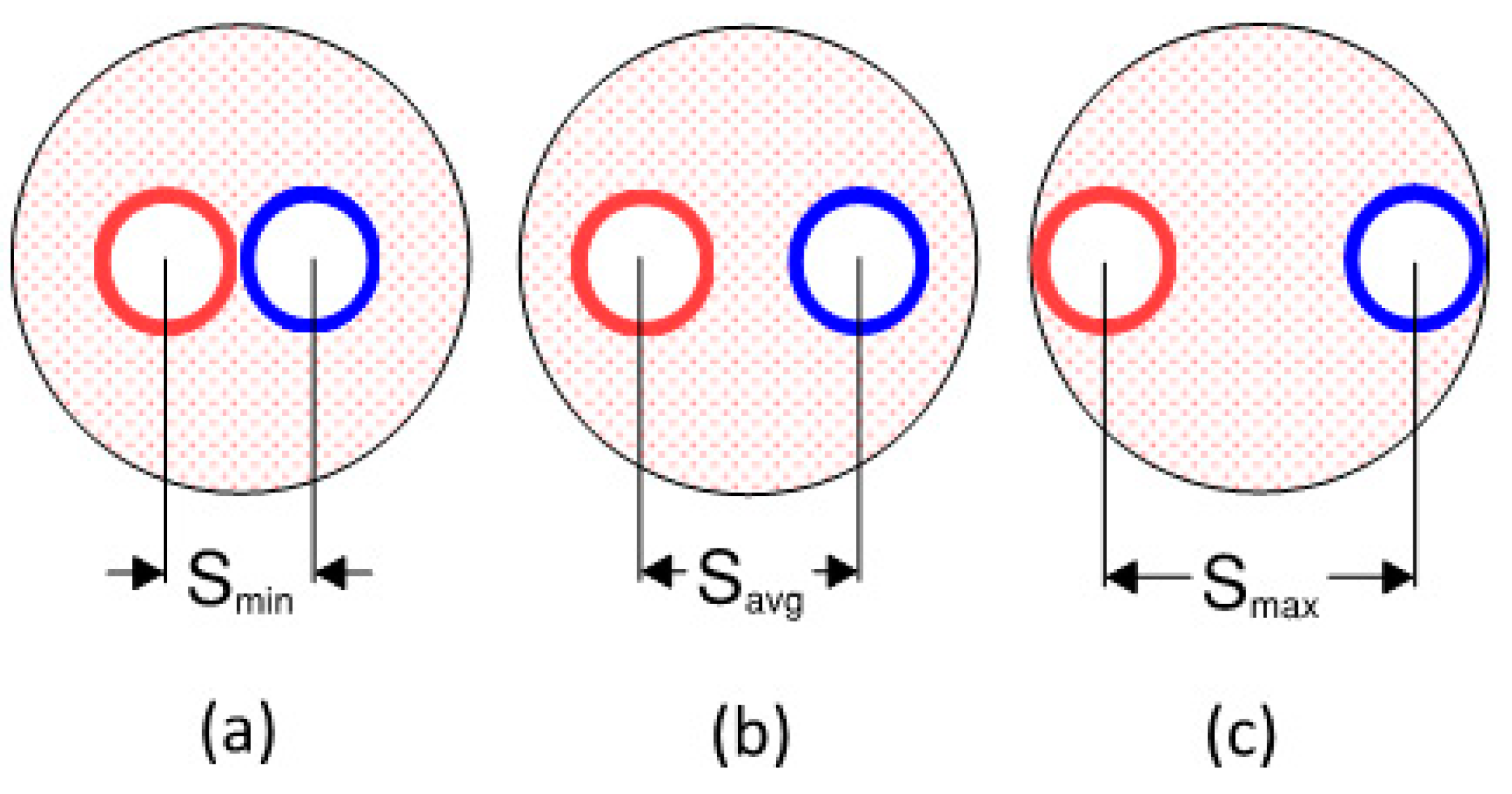

31]. The description of shank spacing is shown in

Figure 4 and covers the whole range of possible shank spacing from minimum to maximum in a symmetrical configuration with pipes in the center of the borehole. To estimate the convective heat transfer coefficient, the flow rate of 0.642 L/s (10.2 USgpm) which is a fully developed turbulent flow under the considered geometry of the U-tube is considered. The properties of water are taken from [

32].

Reynolds number is calculated from Equation (6). Calculation of Nusselt number and convective heat transfer coefficient is from the following equations [

18].

Correlation in Equation (10) is valid for forced convection in fully turbulent flow (condition met when Re ≥ 10,000 for flow in pipes) and is applicable for fluid flow in heating mode [

18]. The physical and thermal properties of the numerical model along with the summary of calculated results for Re, Nu and h are as depicted in

Table 1.

It is to be note that in a borehole of 100 mm with U tube external diameter of 31.8 mm, the maximum shank spacing will be 68.2 mm, however we have considered 68.1 mm as Smax because of the software (FlexPDE 6.51) limitations in providing solution for 68.2 mm shank spacing in a few scenarios.

Finite element triangular meshes were considered for the complete borehole field geometry. The software FlexPDE 6.51 automatically decides the initial mesh size based on the defined geometry and the complexity of the problem. For the borehole region and the soil region near the borehole, finer mesh size was defined. Region “1.1 grout” represents the soil region near the grout/ borehole within a radius of rgo defined as 1.1 times rg. The soil region at the boundary of 1.1 rgo was defined with a finer mesh spacing of dpo/20. For borehole/ grout, the mesh spacing was dpo/30 and that for the U-tube inlet and outlet pipes was dpo/50. With these conditions, numerical analysis on FlexPDE version 6.51 was performed.

2.3. Validation of the Results of the Numerical Model:

Various analytical and semi-analytical equations available for determination of borehole thermal resistance have been numerically assessed and their validity is compared to the results of numerical analysis by previous studies. Analytical models estimate the heat transfer from the borehole wall to the surrounding soil, ignoring the internal borehole region, while numerical models use finite difference or finite volume methods to calculate the temperature distribution throughout the entire domain, including both the surrounding soil and the internal borehole [

36].

Sharqawy et al. [

36] performed a detailed study where the effective pipe-to-borehole thermal resistance in vertical ground heat exchangers was investigated through numerical simulations. A detailed analysis was conducted to identify the dimensionless geometrical parameters that influence this thermal resistance. The heat transfer rates between U-shaped pipes and the borehole were determined numerically and compared with well-established limiting analytical solutions. A dimensionless correlation for the effective pipe-to-borehole thermal resistance was developed. The results of the empirical formula established were also compared with approximate analytical models that treat the U-shaped pipes as a single pipe with an equivalent diameter, as well as with experimental data from the literature. The findings indicated that the existing models do not provide an accurate representation of the effective pipe-to-borehole thermal resistance.

Lamarche et al. [

37] also performed a detailed study on the various theoretical, empirical and experimental approaches for determining the effective borehole thermal resistance. The multi-pole method (Bennett et al. 1987) was found to be the best fit for determining borehole thermal resistance.

Liao et al. [

38] also proposed an empirical formula for the effective borehole thermal resistance and the dimensionless borehole thermal resistances obtained from the correlation was compared with those from other equations available.

Al-Chalabi [

6] and Abuel-Naga and Al-Chalabi [

39] worked on Equations by Paul [

40], Bennet et al. [

41], Gu and O'Neal [

42], Hellström [

43], Shonder and Beck [

44] and Sharqawy et al. [

36] and found that the equation by Bennet et al. [

41] i.e. Equation (12) as follows, was the closest to PDE solutions. Bennet et al. [

41] utilized multi-pole method. The method uses a series of linear heat sources or sinks to represent the pipes within the circular borehole, allowing for the modeling of borehole configurations with multiple U-tubes, including asymmetrical setups.

The equation by Bennet et al. [

41] does not consider the thickness of the pipe. The work by Al-Chalabi [

6] and Abuel-Naga and Al-Chalabi [

39] was ignoring thickness of U pipe and its thermal conductivity in the numerical analysis, Bennett equation was used.

Javed and Spitler [

45] studied the theoretical formulas and empirical correlations to find the effective borehole thermal resistance. It was found that the solution which is a combination of zeroth-order multipole solution and the correction originating from the first-order multipoles is the best fit for almost all scenarios. It was therefore advised to use the modified first order multipoles method instead of other published methods.

The modified Bennett equation by Javed and Spitler [

45] which accounts for pipe material will give accurate results for the study which accounts for the thickness of pipe material.

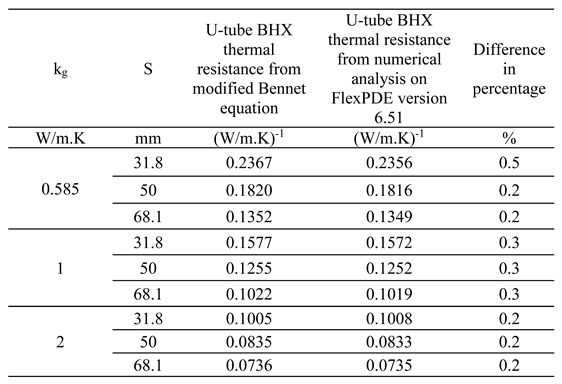

We therefore validated the results of FlexPDE 6.51 with the modified Bennett equation by Javed and Spitler [

45]. The validation was performed for all conditions of the grout and shank spacings considered in the analysis.

Table 2 shows the results of using Equation (17) compared to FlexPDE 6.51 results where the error between the two results was only 0.5% or lesser. This indicates the authenticity of FlexPDE version 6.51 results and further analysis was done using FlexPDE version 6.51.

2.4. Analysis for Insulated Outlet Leg in a Conventional U-Tube Arrangement:

To see the impact of insulation on the outlet leg of the U-tube BHX in reducing the thermal short-circuiting, analysis was performed for the U-tube BHX of the same parameters as defined in

Table 1 with 3 mm closed cell foam insulation on the outlet pipe. The thermal conductivity of the insulation was considered as 0.0342 W/m.K [

46]. Due to insulated outlet leg, the minimum shank spacing was 34.8 mm. Analysis was performed for soil of thermal conductivity 1 W/m.K.

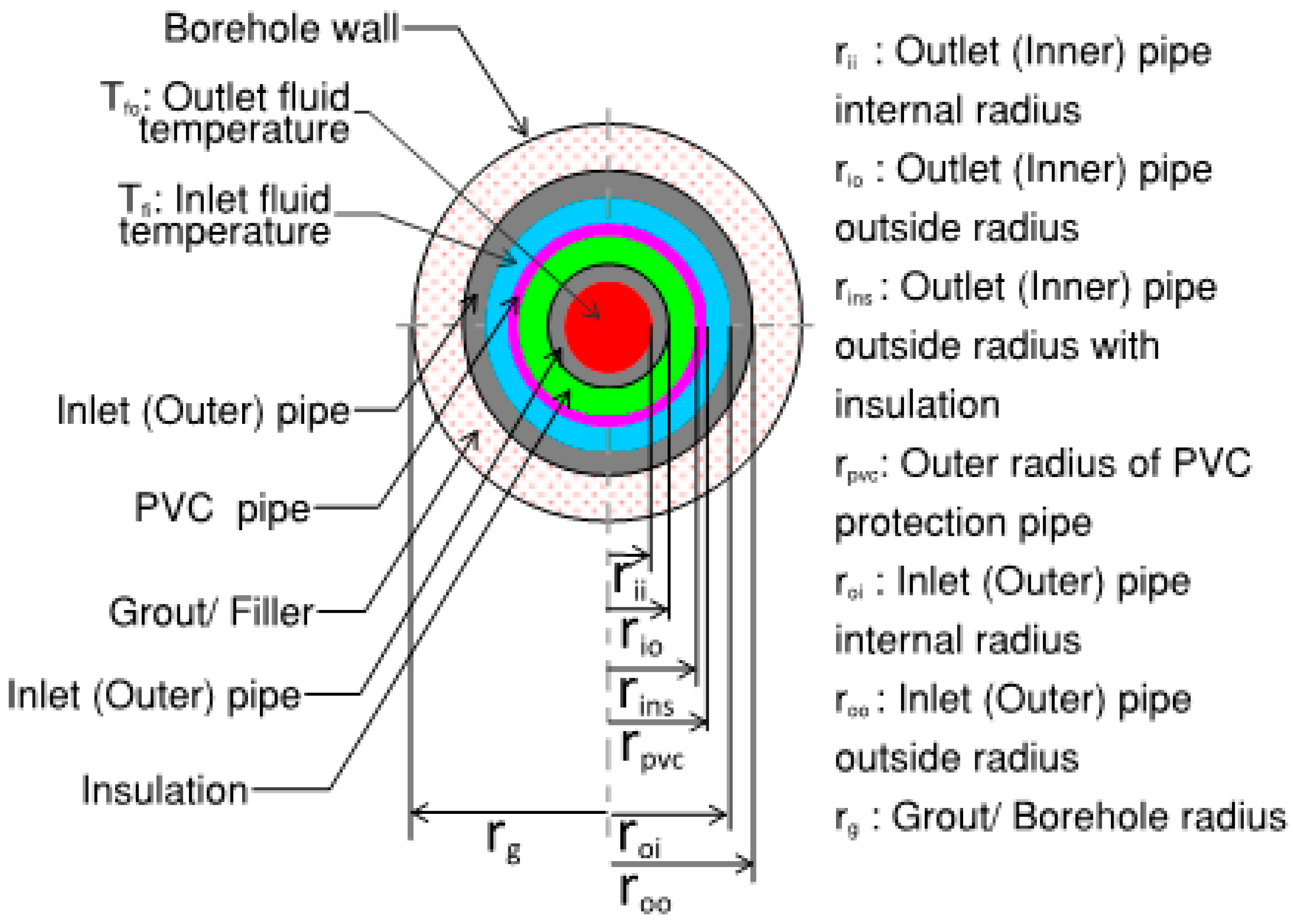

2.5. Analysis for Coaxial Pipe Arrangement:

In the previous literature, the performance of coaxial pipe arrangement was found to be better than U-tube. Therefore, coaxial pipe arrangement was analyzed for the comparison of the improvements in the heat transfer rate. Coaxial pipes were analyzed with water flowing into the borehole through the outer annular pipe, as previous studies have shown this arrangement to be thermally more efficient than the one with inflow from the central pipe [

12].

Unlike U-tube, the outlet (inner) pipe of coaxial arrangement has no direct contact with the grout and exchanges heat solely with the inlet (outer) pipe. As a result, short-circuiting effects are more evident in uninsulated coaxial pipe arrangements because of the significantly increased thermal pathway between the inlet and outlet pipes, Lamarche [

5]. Due to the extremely high short-circuiting losses in uninsulated outlet pipe in coaxial arrangement, most of the previous studies recommend insulation on the outlet (inner) pipe of the coaxial arrangement of tubes to minimize the thermal short-circuiting [5, 16]. For insulation of the outlet pipe, the following are few options commonly available:

(a) uniform insulation throughout the BHX which is usually applied by insulating the outlet pipe with insulation applied on its external side. A protective pipe over the insulation is required to protect it from the water damage of the annular pipe [16, 47].

(b) Non-uniform insulation using vacuum insulated pipe (VIT) as the outlet pipe where vacuum is created between two metallic pipes [16, 47].

Because of two-dimensional study, we analyzed coaxial arrangement with a uniform 3 mm insulation of close cell foam on the outlet (inner) pipe under the same operating conditions. To protect the insulation from water, a PVC tube casing was considered. Because, only the fluid in the outlet pipe is directly exposed to the borehole, the fluid temperature for the calculation of borehole thermal resistance is the temperature of the fluid in the outer (inlet) pipe Lamarche [

5].

Figure 5 describes the geometry of the coaxial model.

Grout & soil properties and the fluid temperatures of the model were identical to the U-tube model as summarized in

Table 1. Nusselt number was calculated from the following equations [18, 48-50].

Correlation in Equation (23) is proposed by Gnielinski and is called Gnielinski equation. The equation is valid for 0.1 ≤ Pr ≤ 1,000 and Re > 4,000. According to Gnielinski [

50], f

ann which is the annular pipe friction factor, is different from the friction factor for the circular tube and can be calculated from the following equation.

For the boundary condition of heat transfer at the outer wall with inner wall insulated, Fann is determined by Equation (28) [

50].

Value of K is 1 if the fluid temperature at the wall of the annular pipe and the bulk fluid temperature are considered to be the same [

50].

The other physical and thermal properties of the numerical model along with the summary of calculated results for Re, Nu and h are as depicted in

Table 3.

The resistance network for the arrangement is shown in

Figure 7. Contact thermal resistance was assumed to be negligible for simplification.

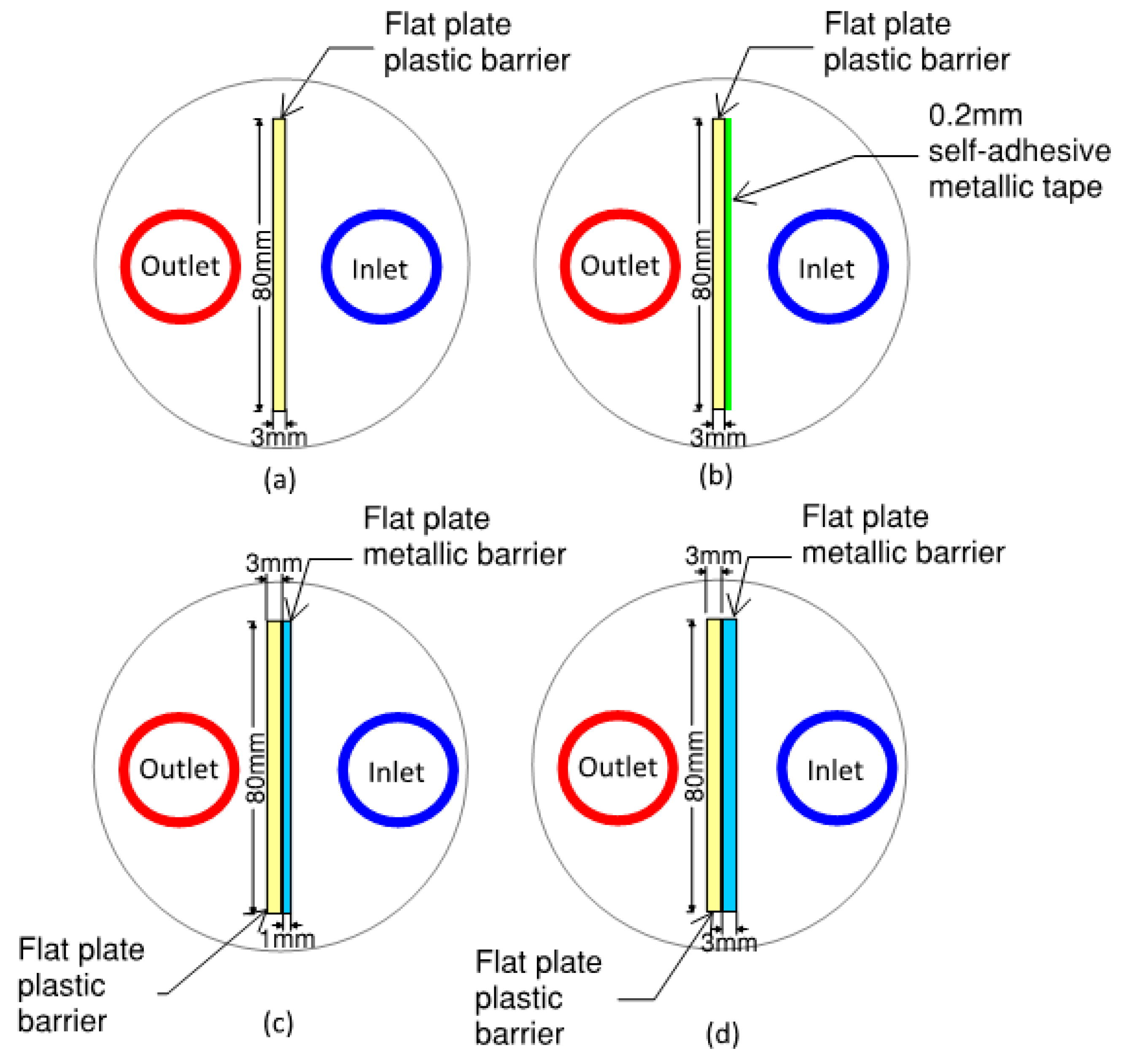

2.6. Analysis for Flat Plate Barrier Arrangement Between the Inlet & Outlet Legs of the U-Tube:

By introducing a flat plate barrier throughout the length of the BHX, the outlet pipe will be thermally separated from the inlet pipe, but its direct contact with the soil and grout will not be restricted. These barrier arrangements were analyzed to see if they lead to a better thermal performance. Several arrangements were analyzed numerically which are listed as follows. Analysis was done for soil thermal conductivity of 0.5, 1 & 2 W/m.K, grout thermal conductivity of 0.585, 1 & 2 W/m.K , minimum, average and maximum shank spacing. The minimum shank spacing due to insertion of the barrier will be more than the minimum shank spacing of 31.8 mm for the conventional U-pipe. If the heat transfer savings of the U-tube with barrier is compared with the conventional U-tube at a lower shank spacing of 31.8 mm, the savings will be misleading because of the comparison with a different shank spacing. Therefore, to depict the sole contribution of the barriers, the results of the analysis are compared to a conventional U-tube BHX with shank spacing S

min-actual.

Figure 8 shows these arrangements diagrammatically.

2.6.1. Flat Plate Plastic Barrier:

To minimize the thermal short circuit losses between the inlet and outlet legs, 3 mm thick and 80 mm long plastic barrier as shown in

Figure 8a were analyzed. Following thermal conductivity for the plastic barriers were analyzed:

Barrier nomenclature FSB-3PL1: 3 mm flat plate shape plastic barrier of thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K. This may be an unplasticized polyvinyl chloride pipe (uPVC) material which is commonly available [

54].

Barrier nomenclature FSB-3PL2: 3 mm flat plate shape plastic barrier of thermal conductivity 0.5 W/m.K. This may be a specialized rigid plastic material [

55].

Barrier nomenclature FSB-3PL3: 3 mm flat plate shape plastic barrier of thermal conductivity 2 W/m.K. This may be a specialized rigid plastic material [

55].

The thickness of the barrier was considered according to previous study and in the perspective of the strength for its underground installation [

6].

2.6.2. Flat Plate Plastic Barrier with Metallic Tape:

In addition to the attempt to minimize the short-circuit losses with the plastic barrier, a 0.2 mm thermally conductive metallic tape was applied to improve the thermal distribution of the inlet pipe. Barrier nomenclature FSB-3PLMT is used for this arrangement. Metallic tapes are common in heat transfer and electronics applications. The thermal conductivity of these tapes is dependent on the thermal conductivity of the metal used, the percentage of impurities in the metal and the thermal conductivity of the adhesive. Copper tapes usually have thermal conductivity in the range of 200-250 W/m.K and are usually available in thicknesses up to 0.2 mm [

56].

Figure 8b shows the geometry. The considered tape had an overall thermal conductivity of 200 W/m.K [

56].

2.6.3. Flat Plate Metallic Barrier:

To observe the sole impact of improvement in temperature distribution of inlet pipe, without an attempt to reduce the thermal short-circuit between the two legs by a plastic barrier, metallic barriers were considered with a thickness of 3 mm and a width of 80 mm as shown in

Figure 8a. The following materials were considered as a barrier due to their corrosion resistant properties, which makes them suitable for underground application.

Barrier nomenclature FSB-3SS: 3 mm flat plate shape stainless steel SS304 barrier of thermal conductivity 16 W/m.K [33, 57]

Barrier nomenclature FSB-3BR: 3 mm flat plate shape brass of thermal conductivity 109 W/m.K [

33]

2.6.4. Flat Plate double BARRIER:

Because plastic barrier helps to mitigate short-circuiting losses and metallic barrier helps to enhance the temperature distribution of the inlet pipe, our next analysis was to see the effect of a double flat plate barrier of plastic and metal where flat plate plastic and flat plate metal barriers were combined to form a double flat barrier. The options considered for the analysis were as follows:

Barrier nomenclature FSB-3PL3AL: 4 mm double flat plate shape barrier with 3 mm plastic (thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K) [

54] & 1 mm aluminum (thermal conductivity 237 W/m.K) [

58]. Refer figure 8c.

Barrier nomenclature FSB-3PL3SS: 6 mm double flat plate shape barrier with 3 mm plastic thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K) [

54] & 3 mm stainless steel (thermal conductivity 16 W/m.K) [33, 57]. Refer figure 8d.

Barrier nomenclature FSB-3PL3BR: 6 mm double flat plate shape barrier with 3 mm plastic thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K) [

54] & 3 mm brass (thermal conductivity 109 W/m.K) [

33]. Refer figure 8d.

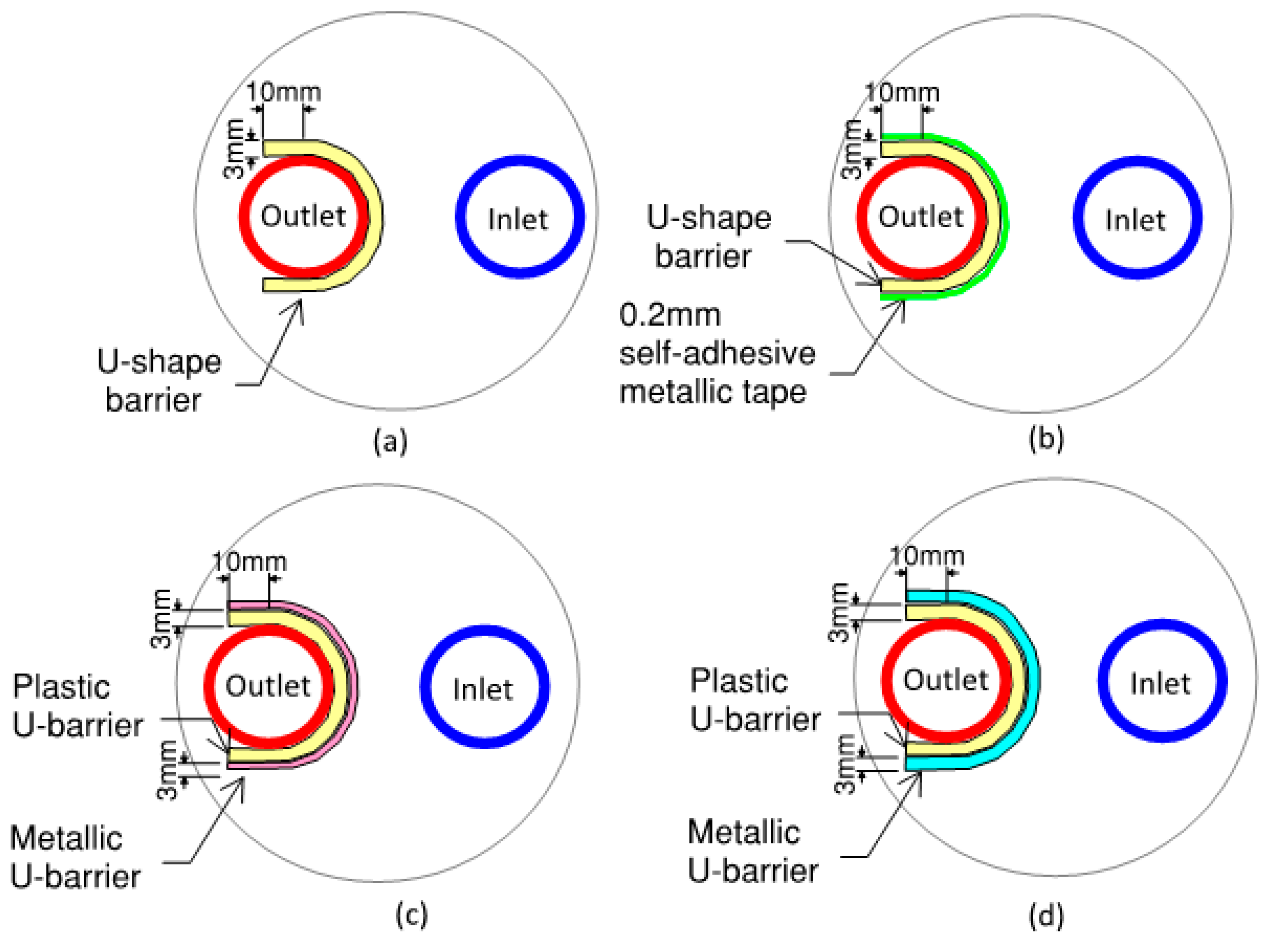

2.7. Analysis of U Shape Barrier Arrangement Between the Inlet & Outlet Legs:

For the outlet pipe, the half of the pipe facing the inlet pipe rejects heat while the other half facing the opposite side takes heat from the surrounding grout and soil. An improvement measure may be analyzed by introducing a U barrier instead of a flat plate barrier, surrounding the half perimeter of the outlet pipe from where it rejects heat and the portion of the pipe which takes heat from the ground is kept free. The barrier will be surrounding the half perimeter of the outlet pipe and extending 10 mm further to prevent the mixing of thermal distribution of the outlet pipe and the inlet pipe.

The thermal properties of the selected materials were the same as considered in the flat plate barrier arrangements. Analysis was done for soil thermal conductivity of 0.5, 1 & 2 W/m.K, grout thermal conductivity of 0.585, 1 & 2 W/m.K , minimum and average and maximum shank spacing. Like the analysis in the flat plate shape barriers, the impact of barriers in heat transfer improvement for maximum shank spacing was not found to be significant and therefore dropped-out for further discussions. Several geometrical arrangements were analyzed numerically which are listed as follows. Figure 12 shows these arrangements schematically.

Barrier nomenclature USB-3PL: U-shape barrier with 3 mm thick plastic of thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K [

54]. Refer

figure 9a.

Barrier nomenclature USB-3PLMT: U-shape barrier with 3 mm thick plastic of thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K [

54] and 0.2 mm self-adhesive metallic tape of an overall thermal conductivity 200 W/m.K [

56]. Refer

figure 9b.

Barrier nomenclature USB-3SS: U-shape barrier with 3 mm thick stainless steel of thermal conductivity 16 W/m.K [33, 57]. Refer

figure 9a.

Barrier nomenclature USB-3BR: U-shape barrier with 3 mm thick brass of thermal conductivity 109 W/m.K [

33]. Refer

figure 9a.

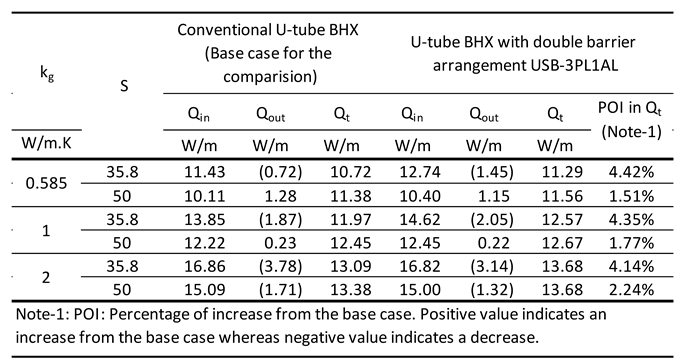

Barrier nomenclature USB-3PL1AL: 4 mm double U-shape barrier with 3 mm plastic (thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K [

54]) & 1 mm aluminum (thermal conductivity 237 W/m.K [

58]). Refer

figure 9c.

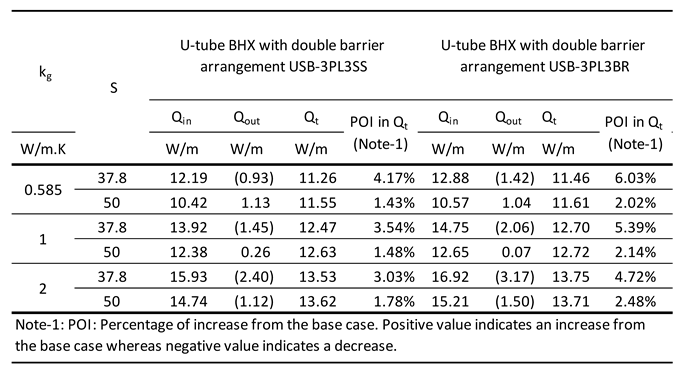

Barrier nomenclature USB-3PL3SS: 6 mm double U-shape barrier with 3 mm plastic thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K [

54]) & 3 mm stainless steel (thermal conductivity 16 W/m.K [33, 57]). Refer

figure 9d.

Barrier nomenclature USB-3PL3BR: 6 mm double U-shape barrier with 3 mm plastic thermal conductivity 0.17 W/m.K [

54]) & 3 mm brass (thermal conductivity 109 W/m.K) [

33]. Refer

figure 9d.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison of this Study with the Previous Studies:

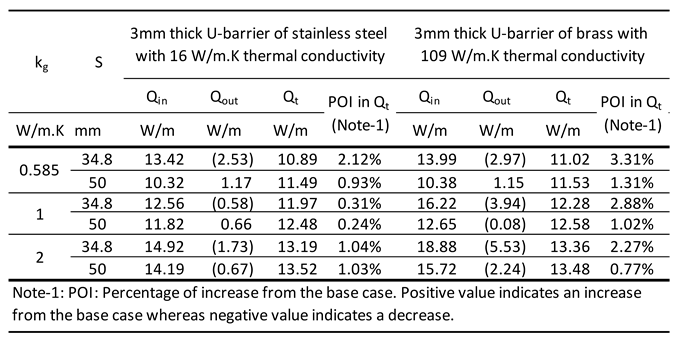

The barrier analysis conducted by Al-Chalabi [

6] was based on a k

g/k

s value of 2 with d

b/d

p value of 3.33. The ratio d

b/d

p in our analysis was 3.15; which is considered to be approximately equal to the value in the study by Al-Chalabi [

6], for the comparison. The far-field radius was 1 m in both studies. The values of thermal conductivities of the barrier materials and their geometry were identical. The previous study mentioned the results corresponding to the ratio k

g/k

s which has a value of 2 in the previous study. In this study, k

g/k

s value of 2 will be equivalent to the following two scenarios:

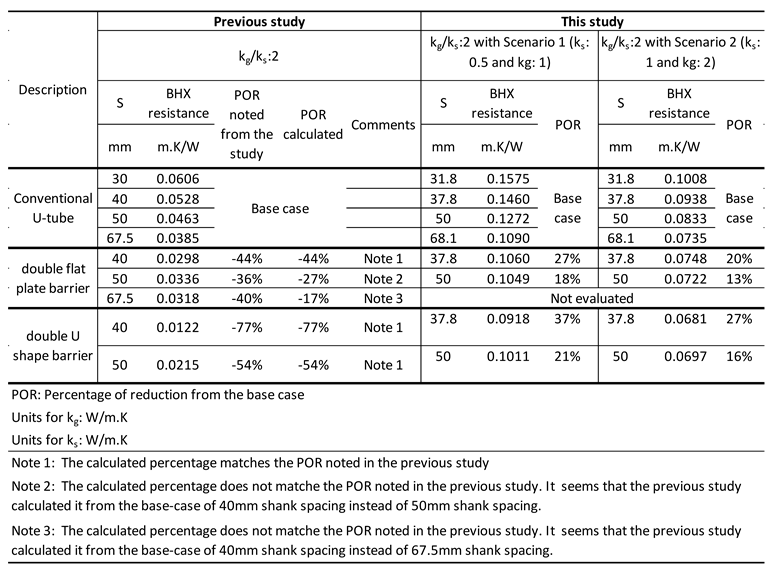

The comparative summary of the results of the analysis by Al-Chalabi [

6] and the relevant results in our analysis are depicted in

Table 15.

The previous study presents the results in terms of ratio kg/ks which was set as 2; however as per this study, the results of heat transfer rate & borehole thermal resistance for two scenarios of identical kg/ks ratio, but different values of kg and ks resulted in a different result of the value of borehole thermal resistance.

The values of borehole thermal resistance between this and the previous study do not match with lower values in the previous study. This is because of not considering the thickness of HDPE pipe in the analysis and therefore the resistance of pipe material in not added in the BHX thermal resistance. In addition, it is noted in this study that increasing the soil thermal conductivity decreases the borehole thermal resistance for the same kg/ks ratio so the difference of values in the two studies might also be a due to use of non-similar conditions of ks and kg.

In this study, the barrier technique is found to be more effective in decreasing the BHX resistance for a lower kg/ks ratio. The previous study is based on a higher value of kg/ks, therefore lacks the analysis for the scenarios where barrier technique may perform more effectively.

The previous study discusses only the percentage reduction in the thermal resistance of the borehole and does not provide an overview of the goal of improving the heat transfer rate or reducing the BHX length. The percentage of borehole thermal resistance in the total resistance of a ground heat exchange system varies with changes in grout thermal conductivity and is more for lower values of thermal conductivity grouts and gradually decreases with increase in the grout thermal conductivity. Therefore, the indication of percentage reduction in the thermal resistance of the borehole will not warrant the effectiveness of the barrier design which offers a higher percentage reduction in borehole thermal resistance. Indication of net heat transfer rate or BHX length reduction instead, may provide a better understanding.

This study fills the gap in the previous study by providing a comprehensive study discussing various combinations of soil and grout thermal conductivity with a conclusive indication of heat transfer rates and BHX length reduction.

4.2. Ccomparision of Different Barriers with Conventional U-Tube:

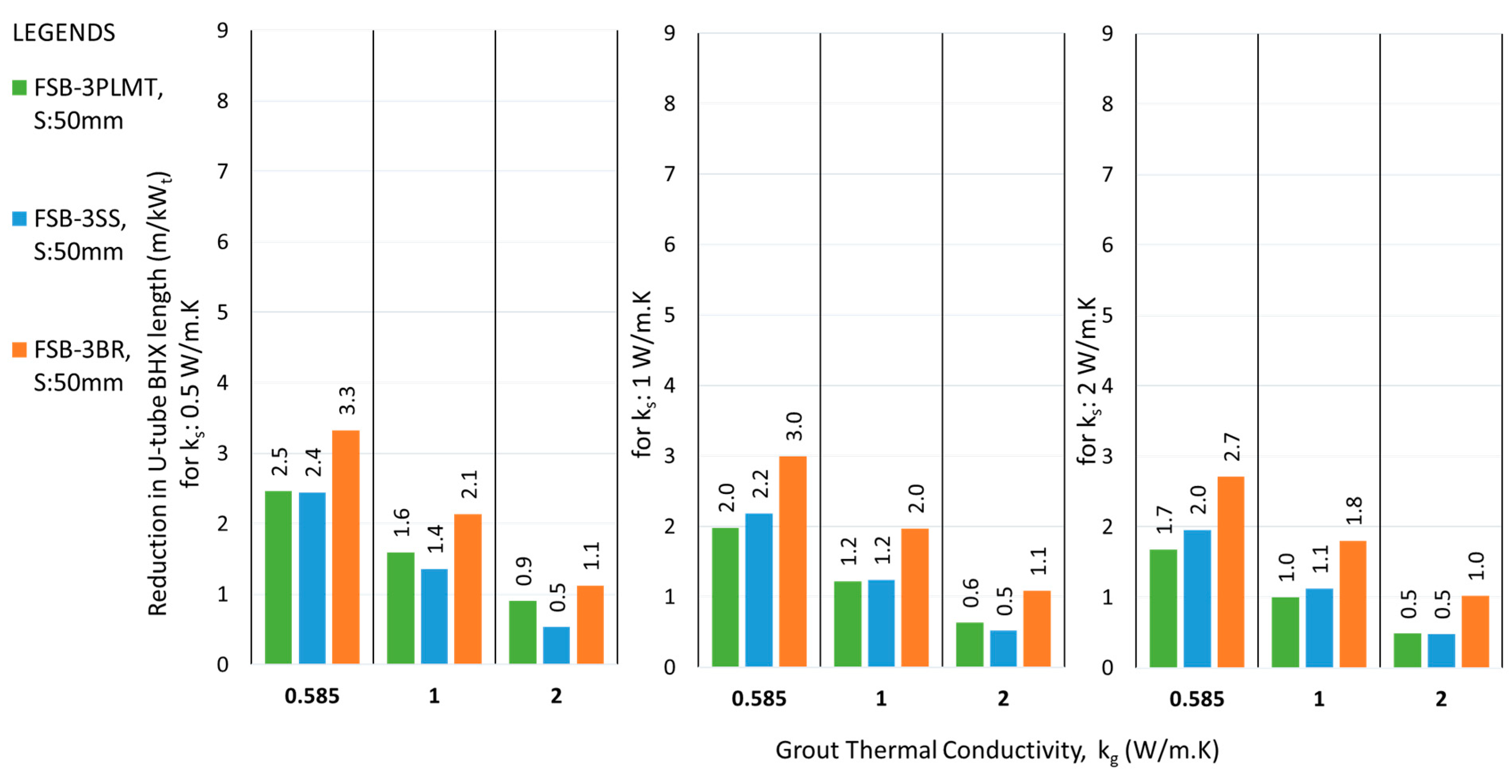

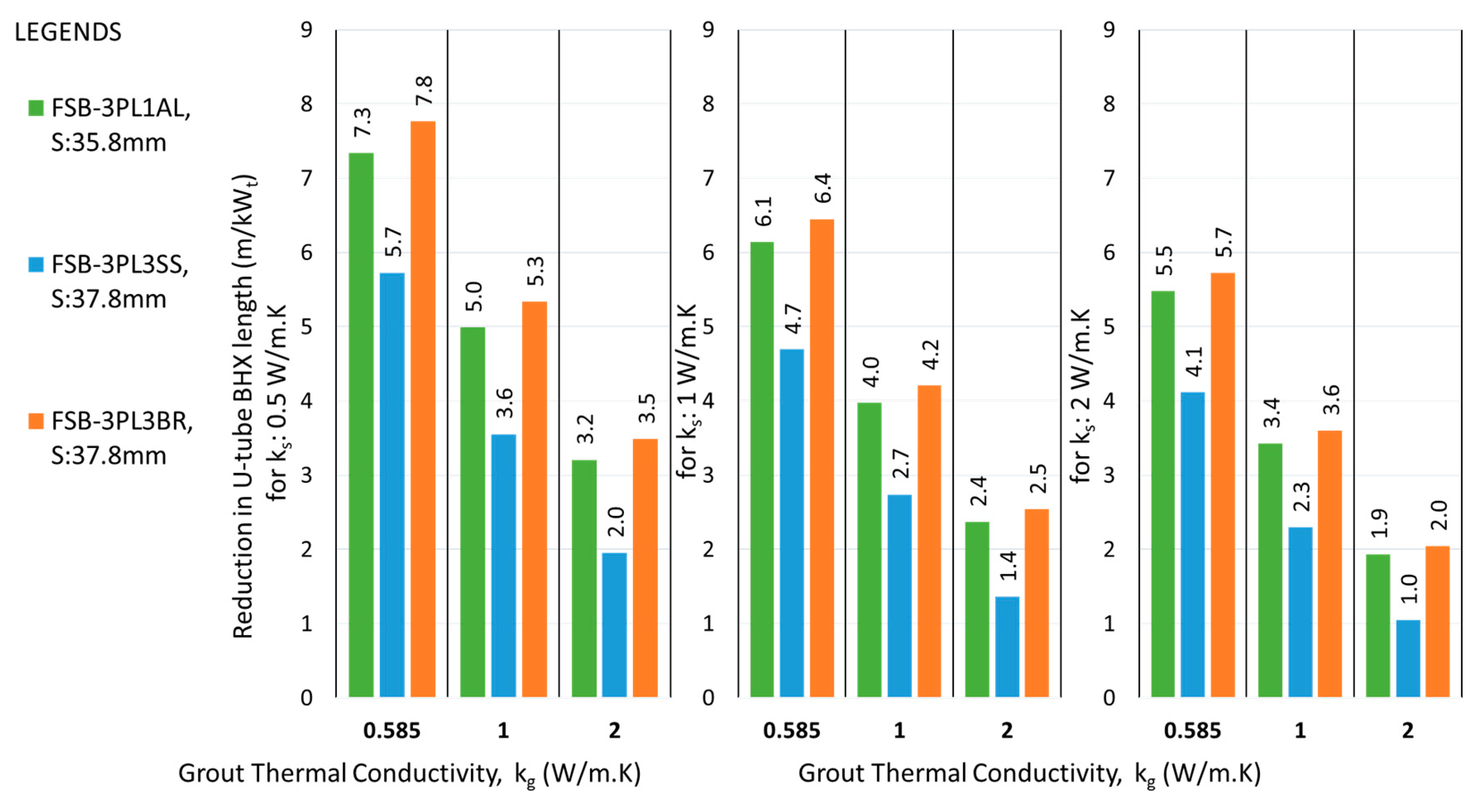

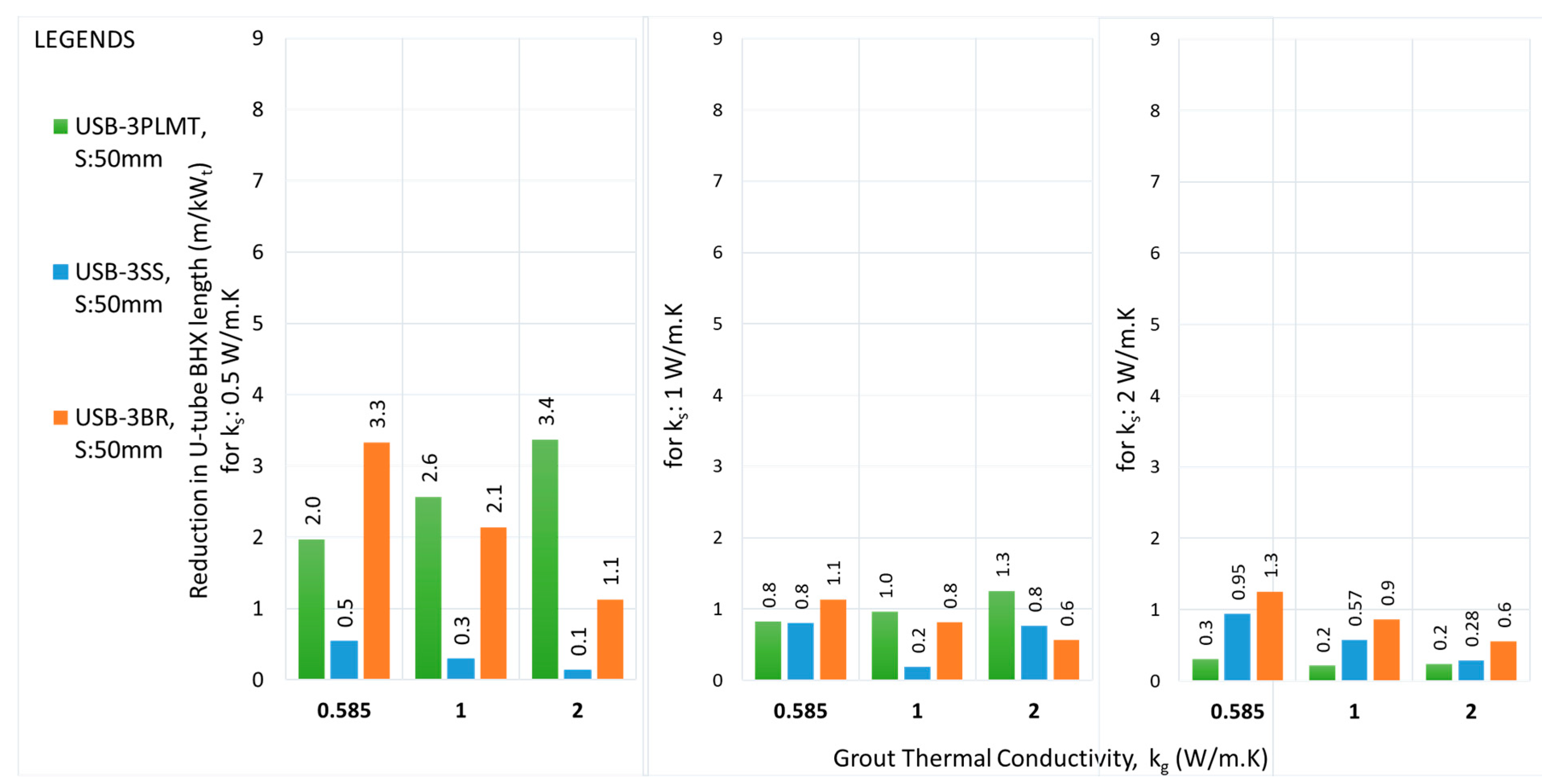

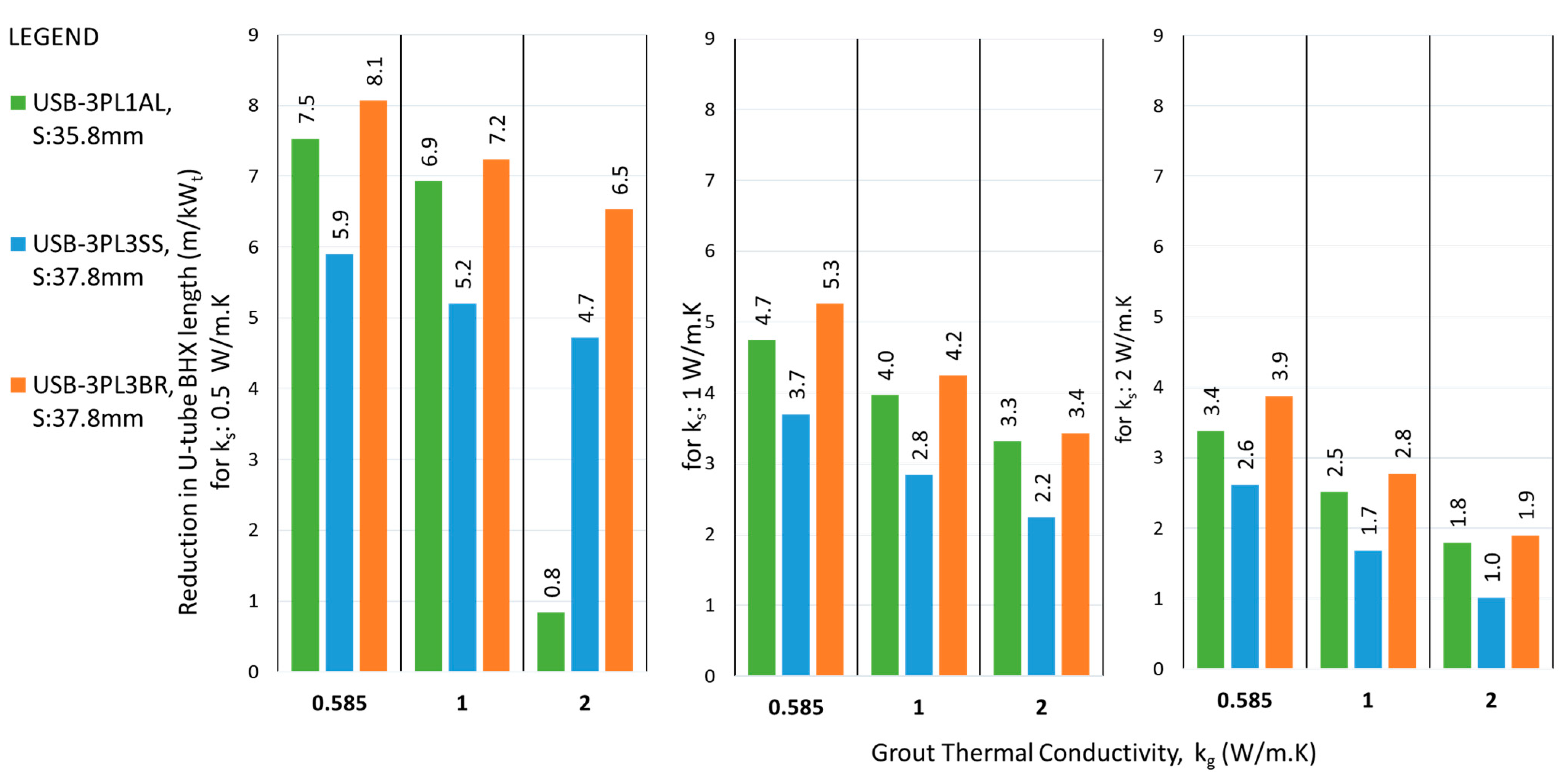

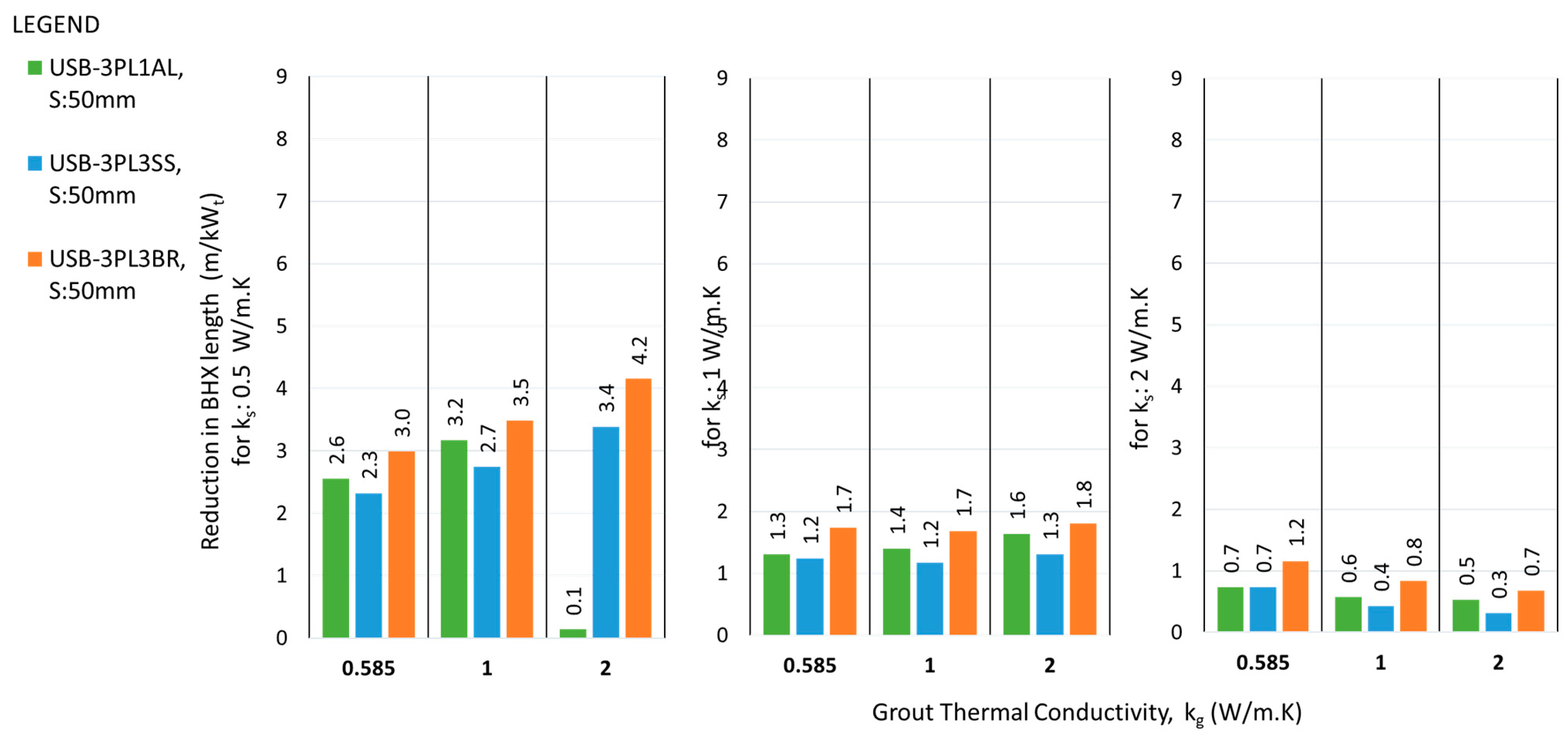

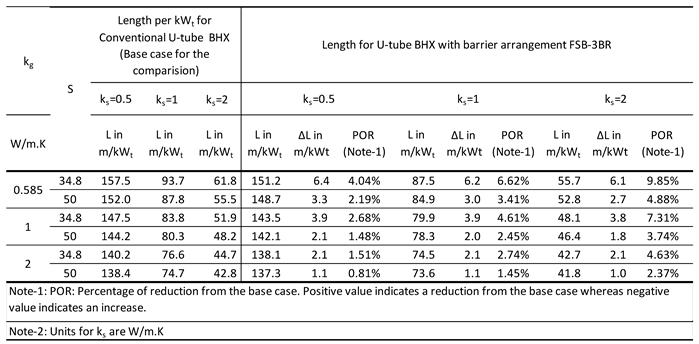

The impact of a barrier between U-tube legs of BHX in reducing the length is better for closer shank spacing than average shank spacing. For example, the saving in U-tube BHX length reduces from 6.4 to 3.3 m/kW

t, for the case of FSB-3BR with k

s of 0.5 W/m.K and k

g of 0.585 W/m.K, when shank spacing is increased from 34.8 mm to 50 mm (Refer to

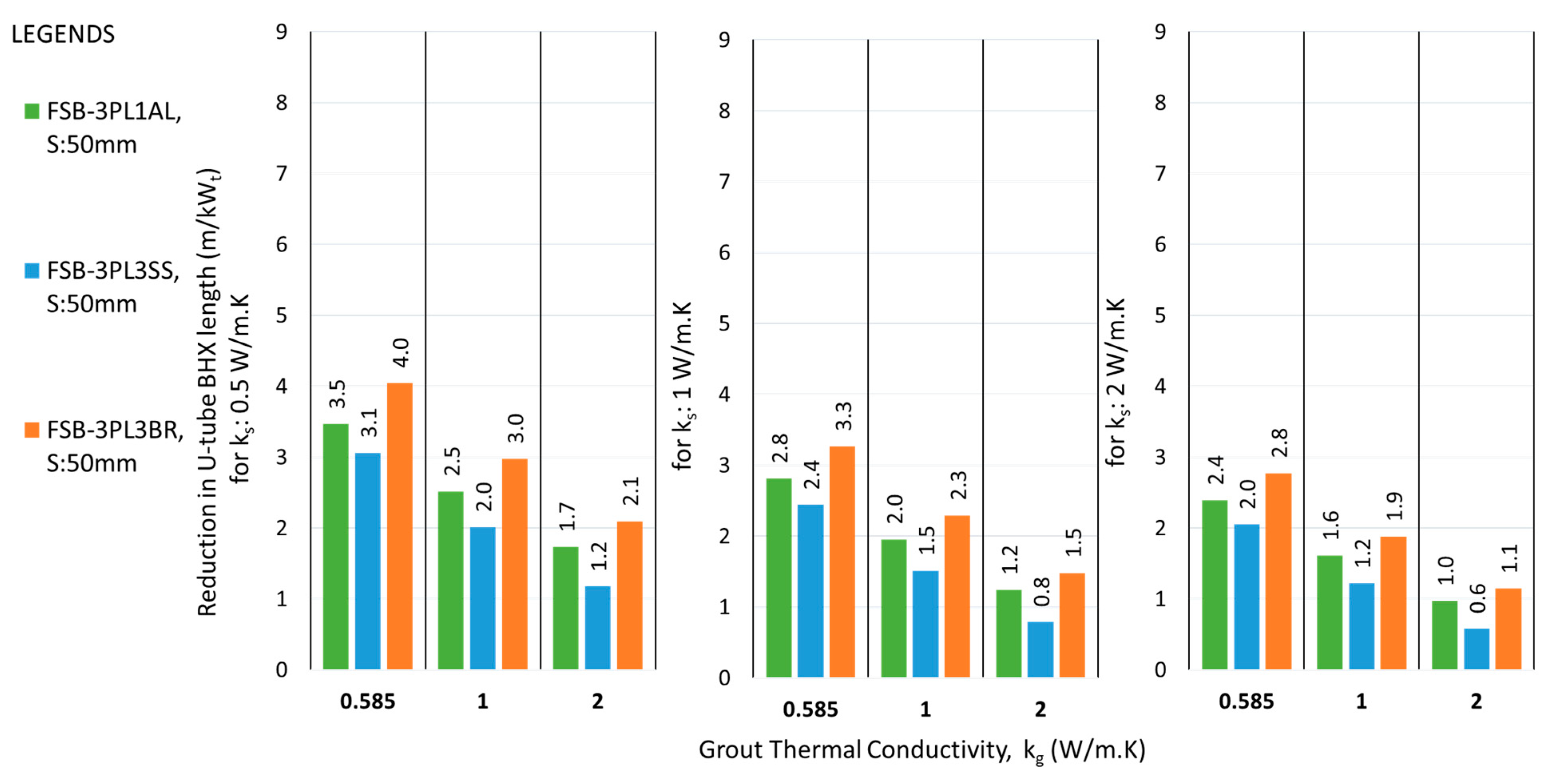

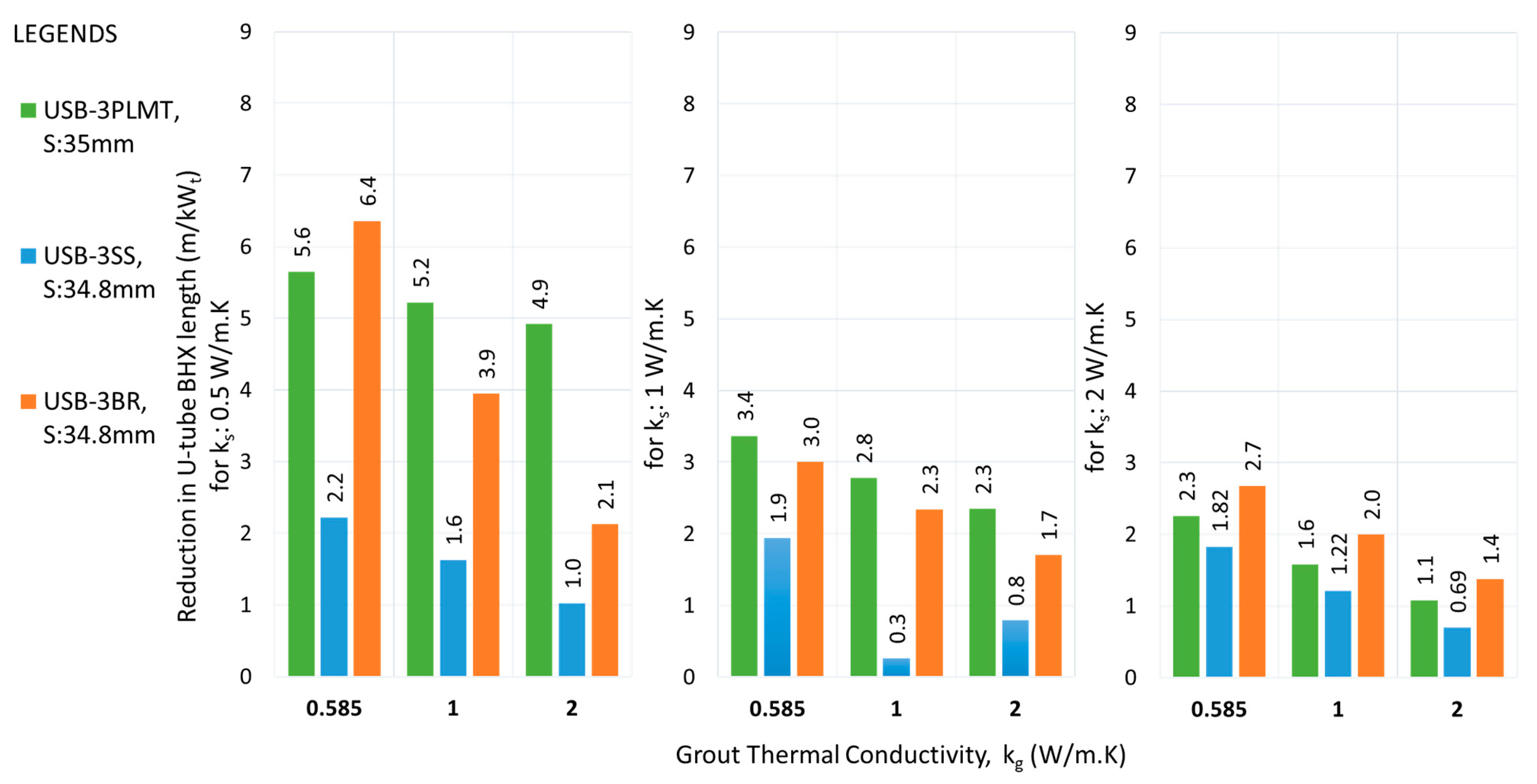

Figure 17). The maximum reduction in absolute length of the BHX due to barrier arrangement was 4 m/kW

t for flat plate barrier when FSB-3PL3BR double flat plate barrier was introduced for S

avg, k

s of 0.5 W/m.K and k

g of 0.585 W/m.K. For the U-shape barrier, the maximum reduction was 4.2 W/m.K when USB-3PL3BR double flat plate barrier was introduced for S

avg, k

s of 0.5 W/m.K and k

g of 2 W/m.K.

The absolute reduction in length was found to be more for lower thermal conductivity grout, except for the case of double U-barriers with average shank spacing, where the absolute reduction for higher thermal conductivity grout was found to be more.

The performance of flat plate-shaped barriers does not show a significant variation across different soil thermal conductivities when the grout thermal conductivity remains constant. However, this difference becomes quite pronounced for U-shaped barriers. For example, the reduction in BHX length for the case of FSB-3BR at Smin & kg of 0.585 W/m.K, is 6.4, 6.2 & 6.1 m/kWt for soil thermal conductivity of 0.5,1 & 2 W/m.K respectively; whereas for the case of USB-3BR at Smin & kg of 0.585 W/m.K, the reduction was 6.4, 3.0 & 2.7 m/kWt for soil thermal conductivity of 0.5,1 & 2 W/m.K respectively.

The performance of double U-barrier USB-3PL3BR was found to be the best out of various single and double barriers of U-shaped. The same trend was noted for flat shape barrier also where FSB-3PL3BR was the best in thermal performance.

The performance of flat plate barrier arrangement FSB-3PLMT was found to be better than FSB-3SS for almost all scenarios of shank spacing, ks and kg; the same trend followed for U-shape barrier also where USB-3PLMT outperformed USB-3SS.

The absolute reduction in length achieved by using a double flat plate barrier was not twice that of the single metallic barrier under the same operating conditions, but instead showed a slight increase. For instance, with ks of 0.5 W/m.K and kg of 0.585 W/m.K, the BHX length reduction was improved from 6.4 m/kWt to 7.8 m/kWt, representing a further reduction of 1.4 m/kWt (or 22%) between the FSB-3BR and FSB-3PL3BR. This trend was even less pronounced at higher soil thermal conductivities of 1 and 2 W/m.K. For U-shaped barriers, the trend showed a marginal improvement over flat plate barrier.

4.3. Overall Comparison of Different Ground Heat Exchange Systems Discussed in This Study:

The design of the insulated outlet leg of the U-tube BHX was found to be ineffective in improving the heat transfer rate of the BHX. Design for the coaxial pipe arrangement showed the arrangement suitable to improve the heat transfer for medium and high thermal conductivity soil of 1 & 2 W/m.K. For soil with low thermal conductivity of 0.5 W/m.K, the significant short-circuit losses in coaxial pipes make the conventional U-tube a more favorable option compared to coaxial pipes.

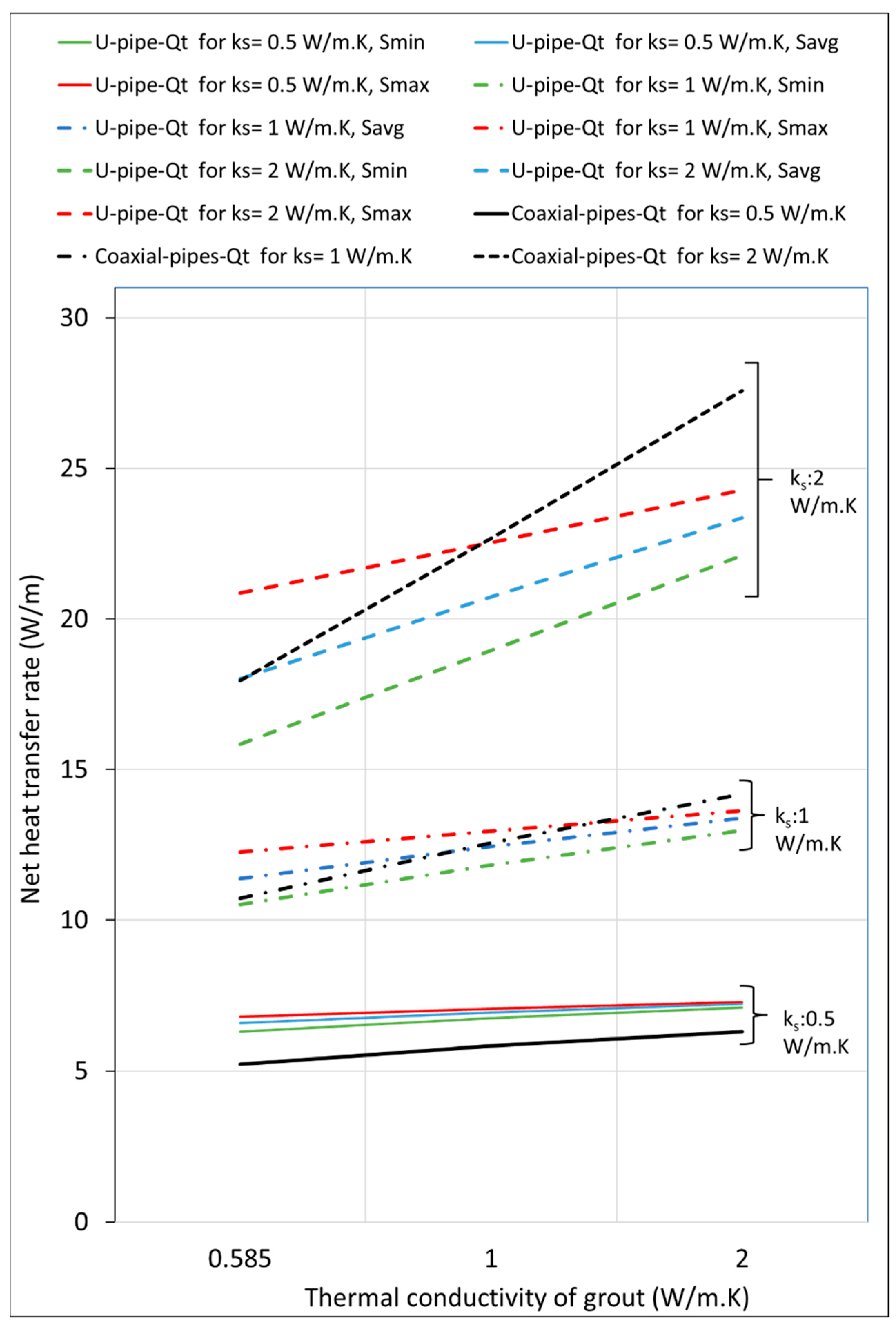

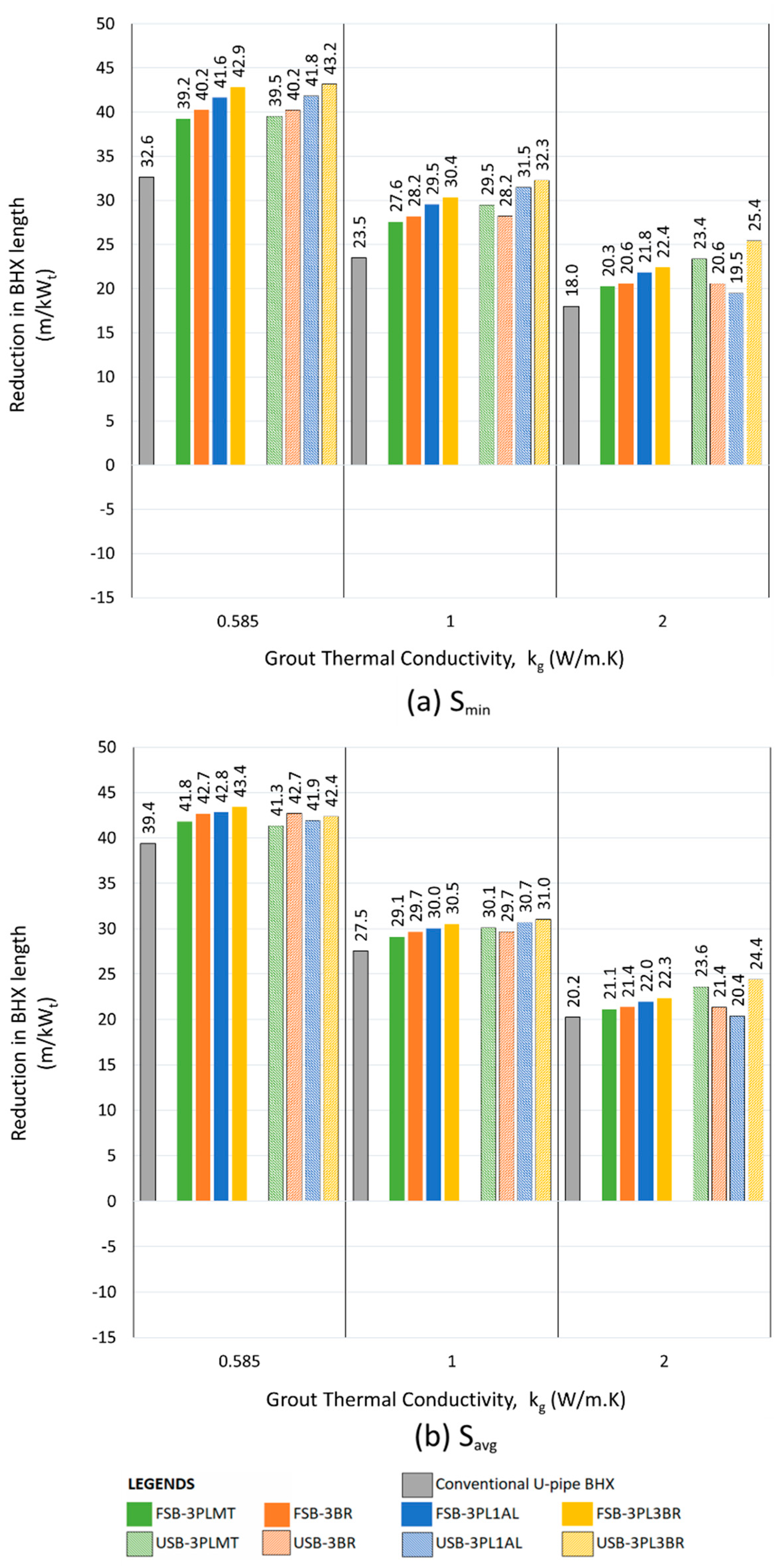

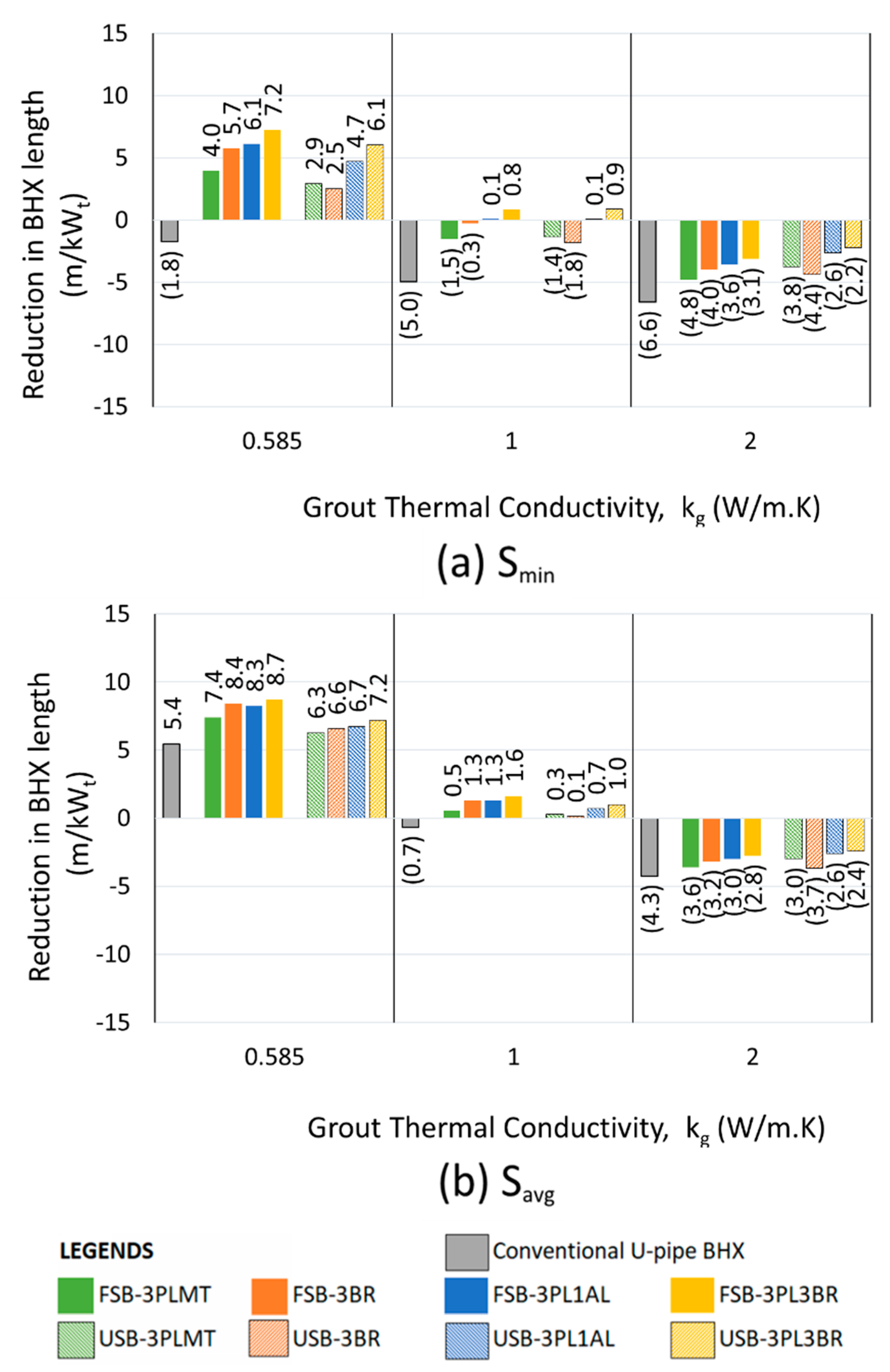

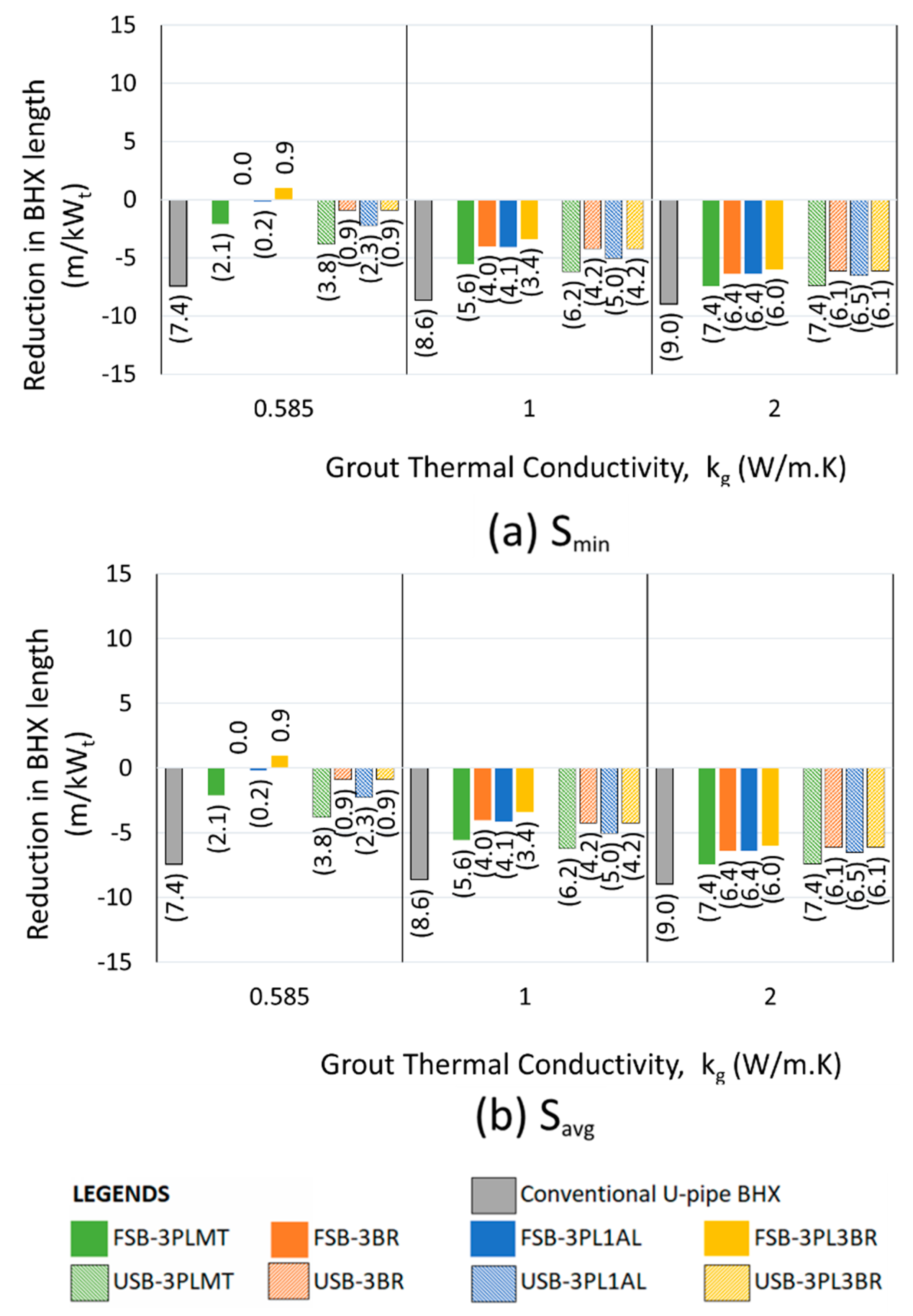

Figure 25 to

Figure 27 show the absolute reduction in the BHX length compared to the coaxial pipe arrangement for k

s of 0.5, 1 and 2 W/m.K respectively. The figures show the length reduction for the conventional U-tube BHX and for different scenarios of U-tube BHX with single and double barriers. The performance of the stainless-steel barrier options (FSB-3SS and USB-3SS) was found to be comparable to or lower than that of the FSB-3PLMT and USB-3PLMT options in most scenarios. As a result, for simplicity, the single stainless-steel barrier options have been omitted from these figures. Similarly, the performance of FSB-3PL3SS &USB-3PL3SS were found to be less than FSB-3PL1AL & USB-3PL1AL and therefore omitted.

The minimum shank spacing (S

min) for the various U-tube BHX configurations shown in

Figure 25 to

Figure 27 varies depending on the geometry. It is 31.8 mm for the conventional U-tube BHX, 34.8 mm for the FSB-3BR and USB-3BR, 35 mm for the FSB-3PLMT and USB-3PLMT, 35.8 mm for the FSB-3PL1AL and USB-3PL1AL, and 37.8 mm for the FSB-3PL3BR and USB-3PL3BR. The average shank spacing is 50 mm across all options.

In

Figure 25 to

Figure 27, for the configurations where the performance of the conventional U-tube BHX (without a barrier) is superior to the coaxial pipe arrangement, the contribution of the barrier to reducing the BHX length is the difference in length reduction between the conventional U-tube and the barrier-equipped option. For example, in

Figure 25, with k

s and k

g values of 0.5 and 0.585 W/m.K at S

avg, replacing coaxial pipes with a conventional U-tube BHX reduces the length from 191.4 m/kW

t (for coaxial pipes) to 158.8 m/kW

t (for conventional U-tube). Adding the USB-3PL3BR barrier to the U-tube BHX further reduces the length to 148.2 m/kW

t.

The best-performing barriers were the double barriers made of 3 mm plastic and 3 mm brass, both in flat plate and U-shape configurations. The flat plate barrier FSB-3PL3BR outperformed the U-shape barrier USB-3PL3BR in reducing the BHX length for k

g value of 0.585 W/m.K. However, the USB-3PL3BR demonstrated better performance than the FSB-3PL3BR for k

g value of 2 W/m.K, as shown in

Figure 25 to

Figure 27. The performance difference between FSB-3PL3BR and USB-3PL3BR was minimal for k

g value of 1 W/m.K.

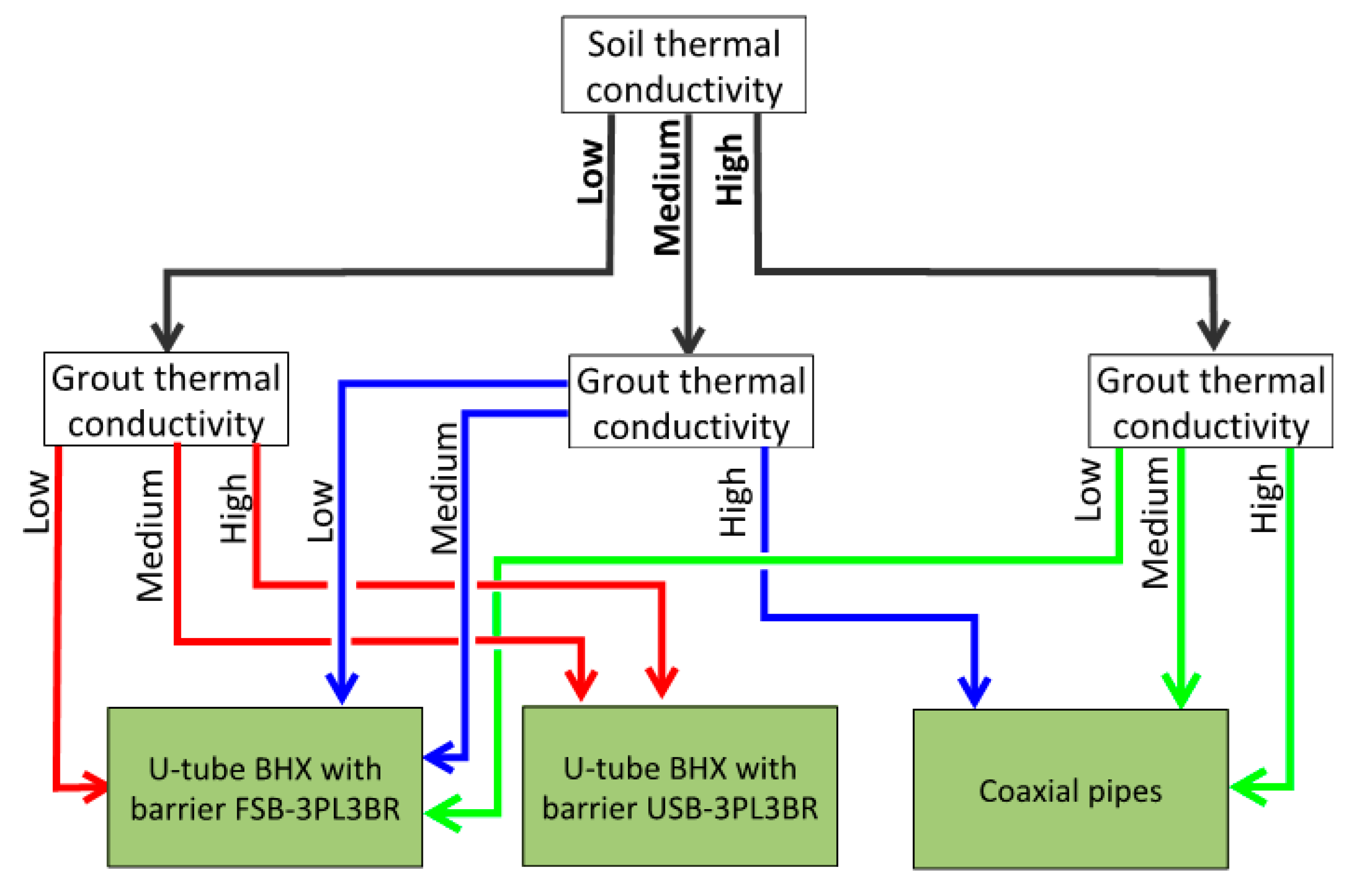

Based on

Figure 25 to

Figure 27, we conclude the decision tree as shown in

Figure 28 for the selection of the best ground heat exchange system to get an optimized length of BHX. Soil of 0.5, 1 and 2 W/m.K is considered as low, medium and high thermal conductivity soil respectively. Grout thermal conductivity of 0.585, 1 and 2 W/m.K is considered low, medium and high respectively.

5. Conclusions

Vertical Ground source heat pumps can be implemented as an economical option for heating/ cooling, subject to its careful designing, especially for the ground loop heat exchanger. Over-designing of this component will lead to uneconomical design, whereas under-designing will lead to discomfort. There is a need to adopt techniques for reducing borehole thermal resistance or in other words to improve the heat transfer process across the BHX.

Various barrier arrangements between the two legs of U-tube BHX have been proposed which provide a viable alternative to conventional U-tube arrangements and serve as a better option than coaxial pipes in certain conditions of soil and grout thermal conductivity.

The options of double barrier arrangement FSB-3PL3BR & USB-3PL3BR have shown the best performance over a conventional U-tube BHX, with a possible saving of 7.8 & 8.1 m in length of BHX per kW of heat transfer respectively for ks of 0.5 W/m.K and kg of 0.585 W/m.K. The other simple option of 3 mm plastic barrier with 0.2 mm metallic tape i.e. barrier arrangements FSB-3PLMT & USB-3PLMT, though offering comparatively lower heat transfer improvements may still perform economically, especially in settings where installation simplicity and cost-effectiveness are prioritized. A reduction of 7.3 & 7.5 m in length of BHX per kW of heat transfer is possible from FSB-3PLMT & USB-3PLMT for ks of 0.5 W/m.K and kg of 0.585 W/m.K.

The study demonstrates that the novel design of various geometries and materials of barrier between the two legs of a U-tube BHX presents viable alternative to conventional U-tube arrangements in ground heat exchanger systems and shows better performance over coaxial pipes for low to medium thermal conductivity soil and grout. Although flat & U-shape barriers with 3 mm plastic & 3 mm brass were the best options of the barrier for length reduction, the other options discussed in the study which showed an improvement in the heat transfer may also be considered based on simplicity in construction or lower cost. A cost-benefit analysis is recommended for the selection of the type of BHX arrangement among the various options discussed for a given soil condition, especially where the difference between various options is marginal.

The study for barrier techniques in this study is limited to two-dimensional steady state analysis. Further numerical study with a three-dimensional analysis may precisely determine the resulting reduction in the BHX length. Dynamic modelling may also help in the précised determination of the overall improvement in the heat transfer for the long-term. A minimum overall barrier thickness of 3 mm has been considered to ensure the strength and stability of the barrier for deep burial in the vertical borehole. Structure analysis for the précised thickness of the barrier may be undertaken for further optimization. The study can be continued for double U-pipe arrangement and other configurations.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram showing BHX; (a & b) Plan & section for U-tube arrangement; (c & d) Plan & section for Coaxial pipe arrangement with inflow through annular pipe.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram showing BHX; (a & b) Plan & section for U-tube arrangement; (c & d) Plan & section for Coaxial pipe arrangement with inflow through annular pipe.

Figure 2.

Thermal resistance network for U-tube BHX.

Figure 2.

Thermal resistance network for U-tube BHX.

Figure 3.

U-tube BHX model geometry.

Figure 3.

U-tube BHX model geometry.

Figure 4.

Various shank spacings of U-tube BHX model.

Figure 4.

Various shank spacings of U-tube BHX model.

Figure 5.

U-tube BHX with insulated outlet pipe

Figure 5.

U-tube BHX with insulated outlet pipe

Figure 6.

Insulated Coaxial pipes model geometry

Figure 6.

Insulated Coaxial pipes model geometry

Figure 7.

Thermal resistance network for coaxial pipes BHX

Figure 7.

Thermal resistance network for coaxial pipes BHX

Figure 8.

Schematic of Flat plate shape barrier arrangements for U-tube BHX.

Figure 8.

Schematic of Flat plate shape barrier arrangements for U-tube BHX.

Figure 9.

Schematic of U-shape barrier arrangements for U-tube BHX.

Figure 9.

Schematic of U-shape barrier arrangements for U-tube BHX.

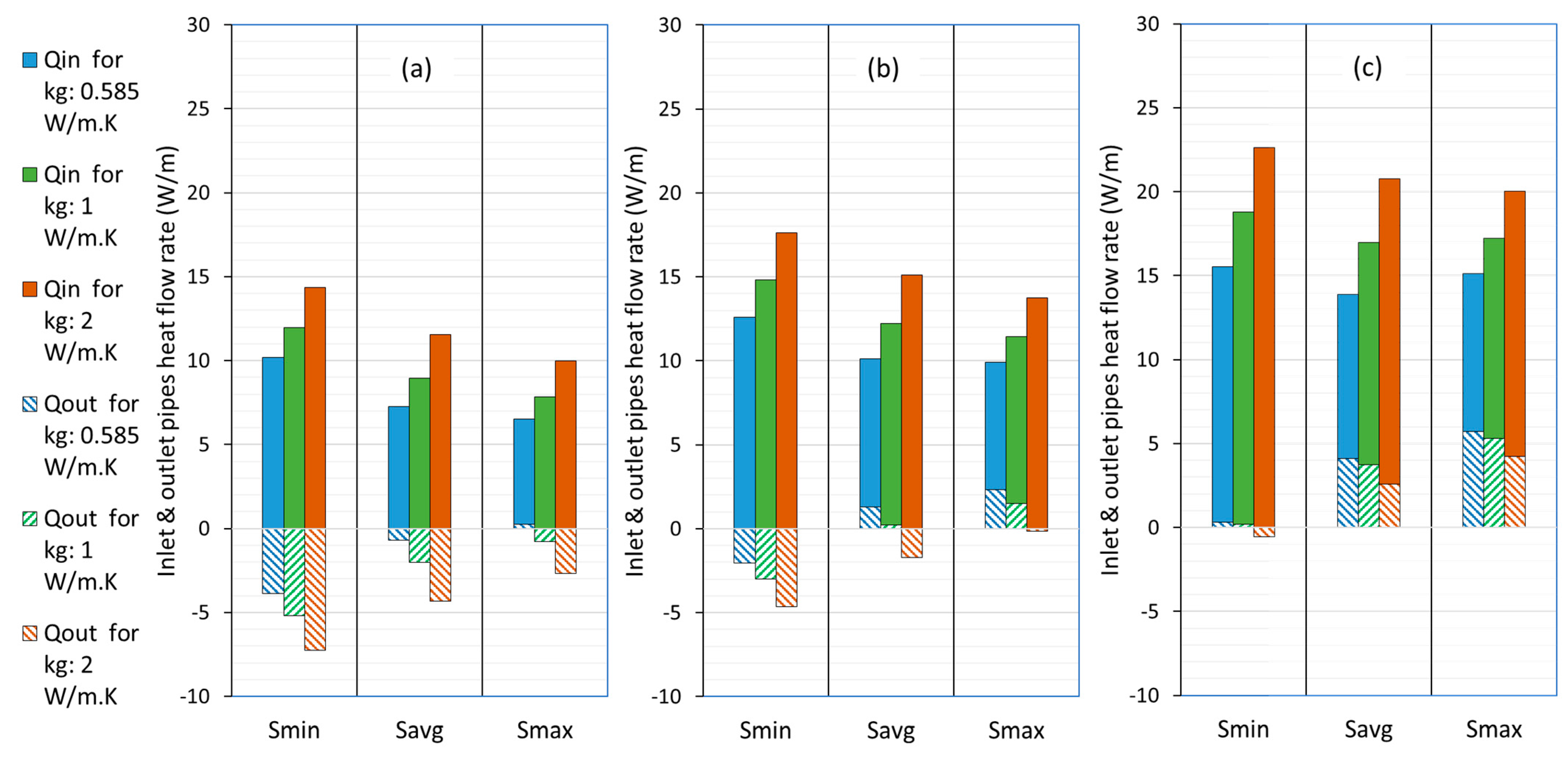

Figure 10.

Heat transfer from U-tube BHX Inlet & Outlet legs; (a) for ks: 0.5 W/m.K (b) for ks: 1 W/m.K (c) for ks: 2 W/m.K

Figure 10.

Heat transfer from U-tube BHX Inlet & Outlet legs; (a) for ks: 0.5 W/m.K (b) for ks: 1 W/m.K (c) for ks: 2 W/m.K

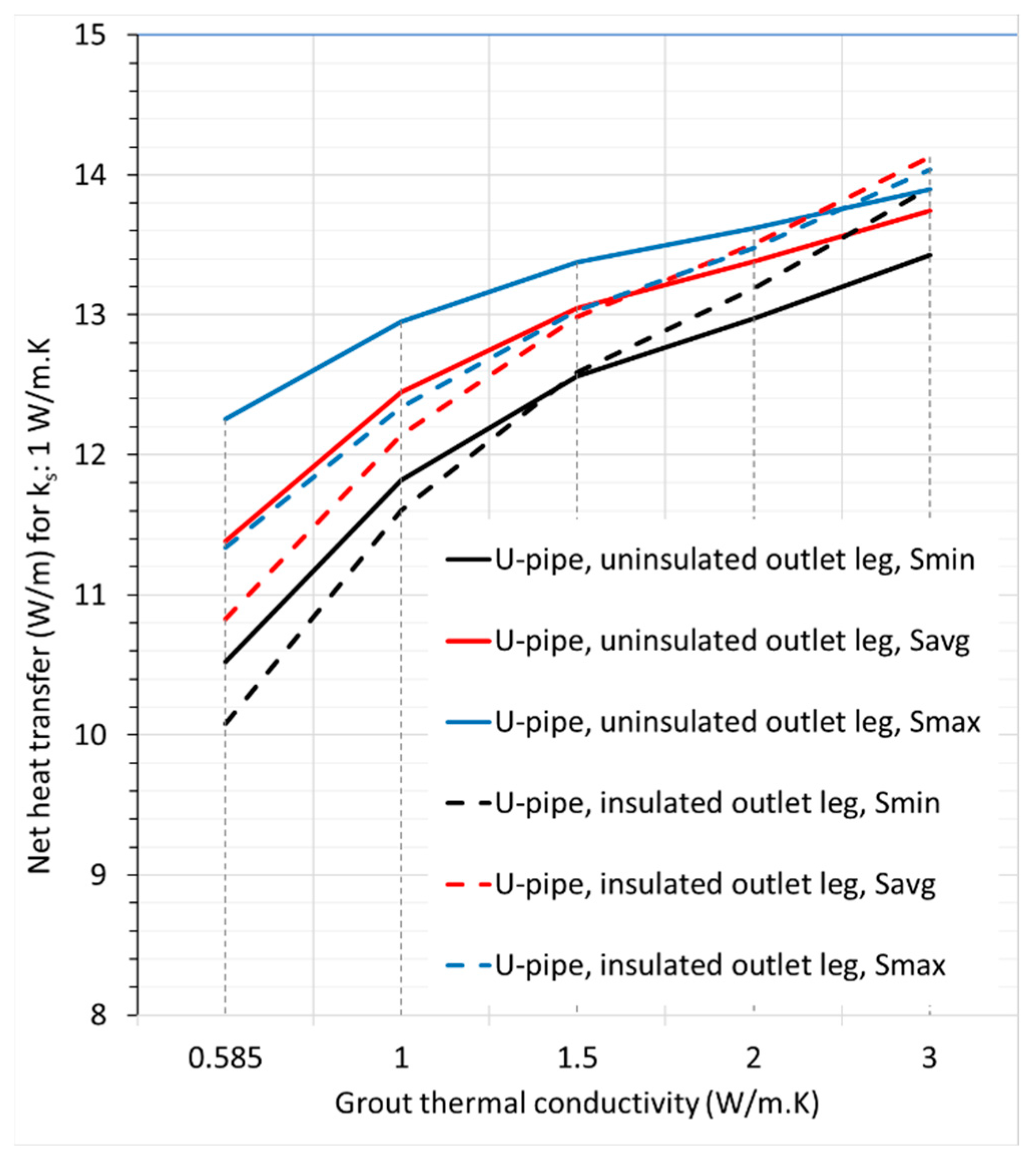

Figure 11.

Comparison of Net heat transfer for uninsulated U-tube and U-tube with insulated outlet leg; ks: 1 W/m.K

Figure 11.

Comparison of Net heat transfer for uninsulated U-tube and U-tube with insulated outlet leg; ks: 1 W/m.K

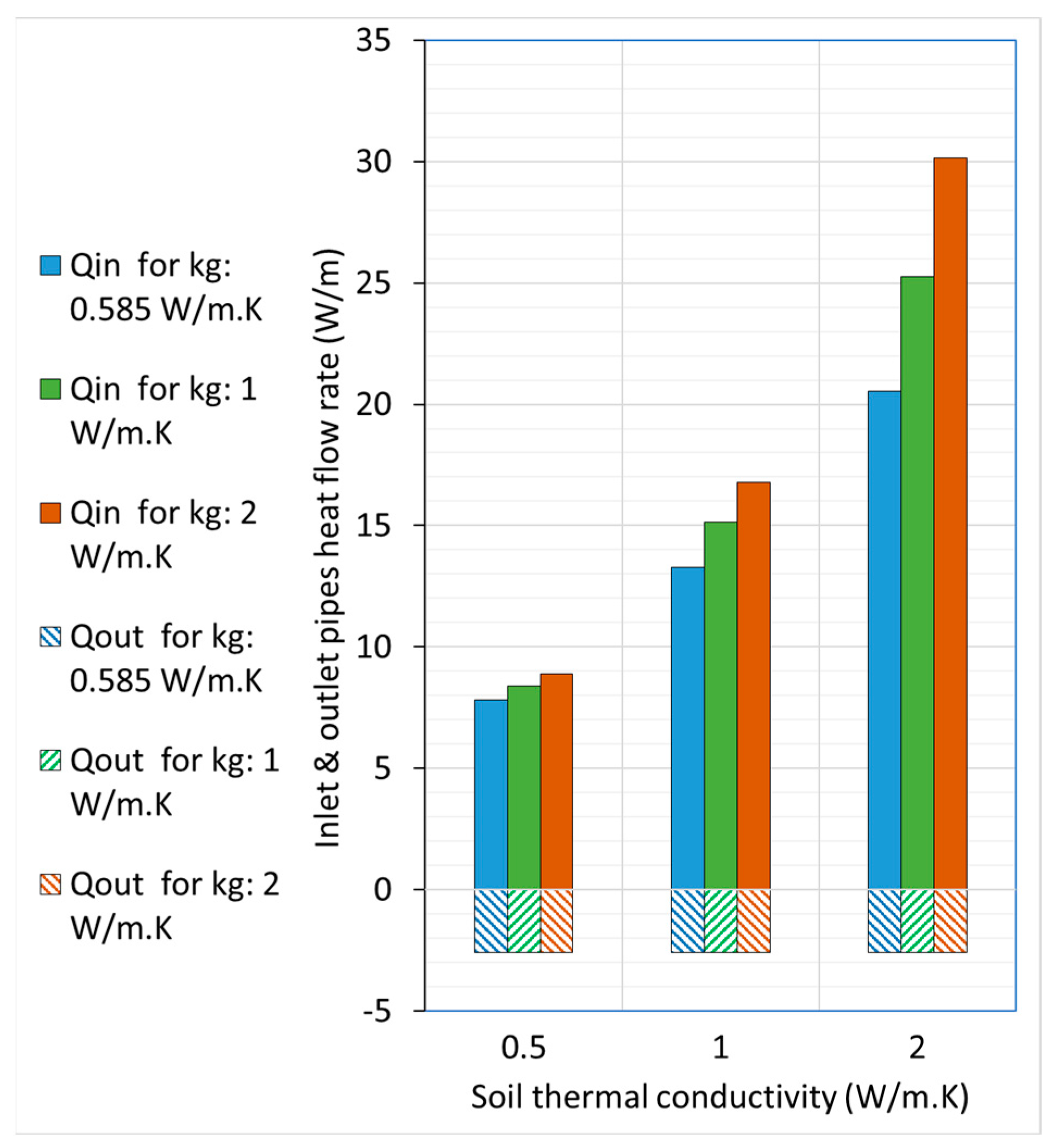

Figure 12.

Heat transfer rate from the inlet & outlet pipes for insulated coaxial pipes (inflow through outer pipe)

Figure 12.

Heat transfer rate from the inlet & outlet pipes for insulated coaxial pipes (inflow through outer pipe)

Figure 13.

Net heat transfer rate for U-tube and coaxial BHXs

Figure 13.

Net heat transfer rate for U-tube and coaxial BHXs

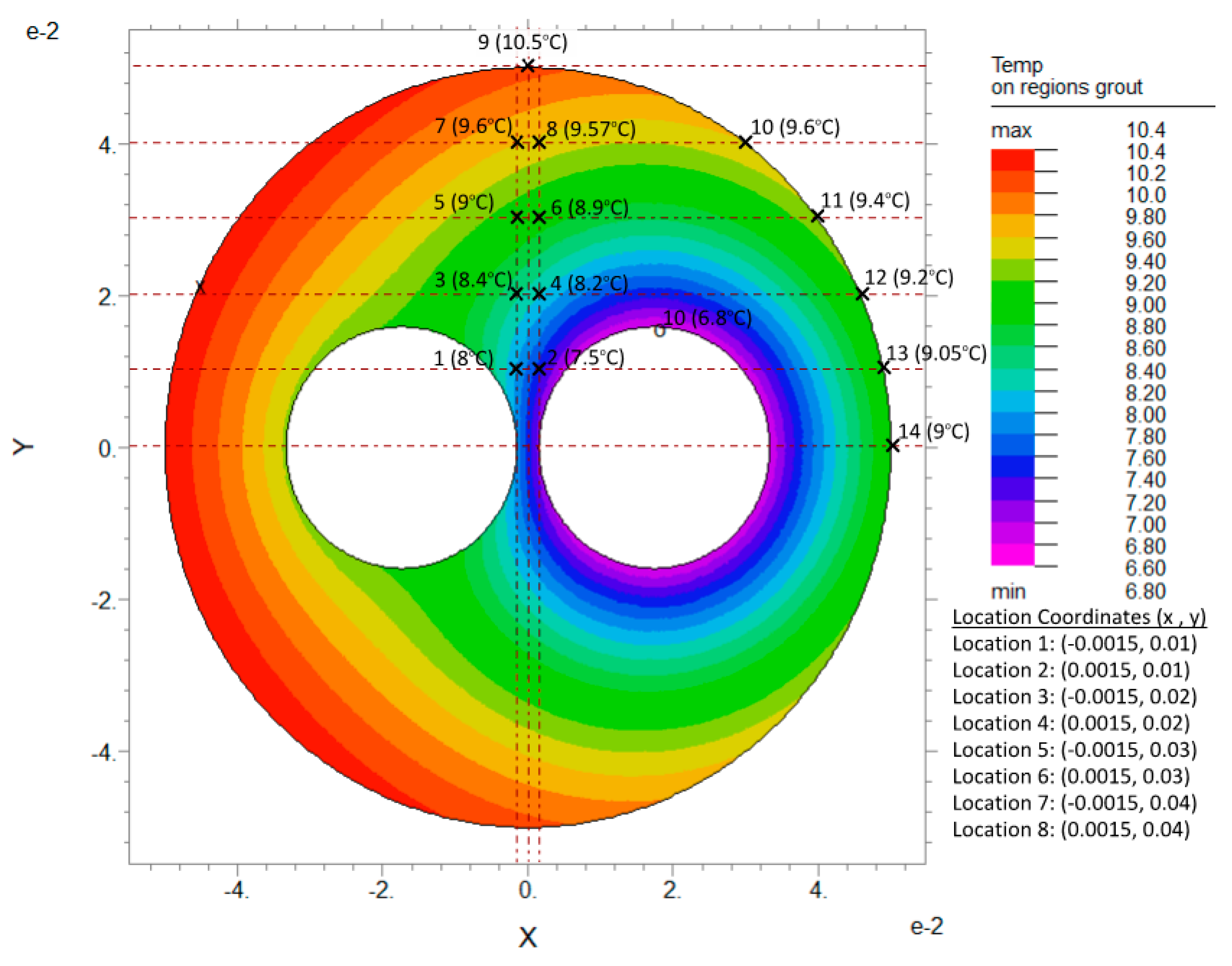

Figure 14.

Temperature distribution in grout region for conventional U-tube BHX, ks: 1 W/m.K, kg: 0.585 W/m.K and S: 34.8 mm.

Figure 14.

Temperature distribution in grout region for conventional U-tube BHX, ks: 1 W/m.K, kg: 0.585 W/m.K and S: 34.8 mm.

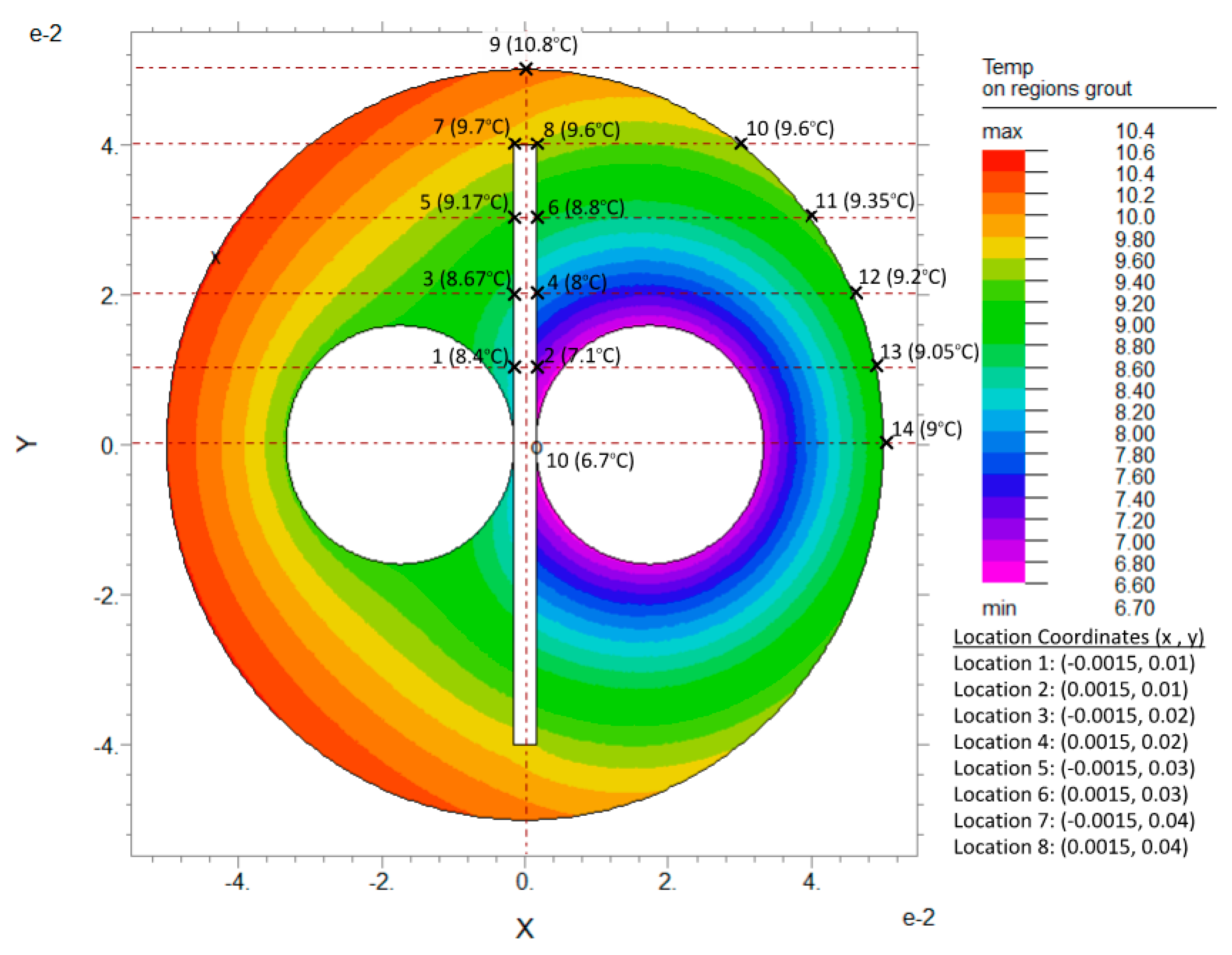

Figure 15.

Temperature distribution in grout region for U-tube BHX with barrier arrangement FSB-3PL1, ks: 1 W/m.K, kg: 0.585 W/m.K and S: 34.8 mm.

Figure 15.

Temperature distribution in grout region for U-tube BHX with barrier arrangement FSB-3PL1, ks: 1 W/m.K, kg: 0.585 W/m.K and S: 34.8 mm.

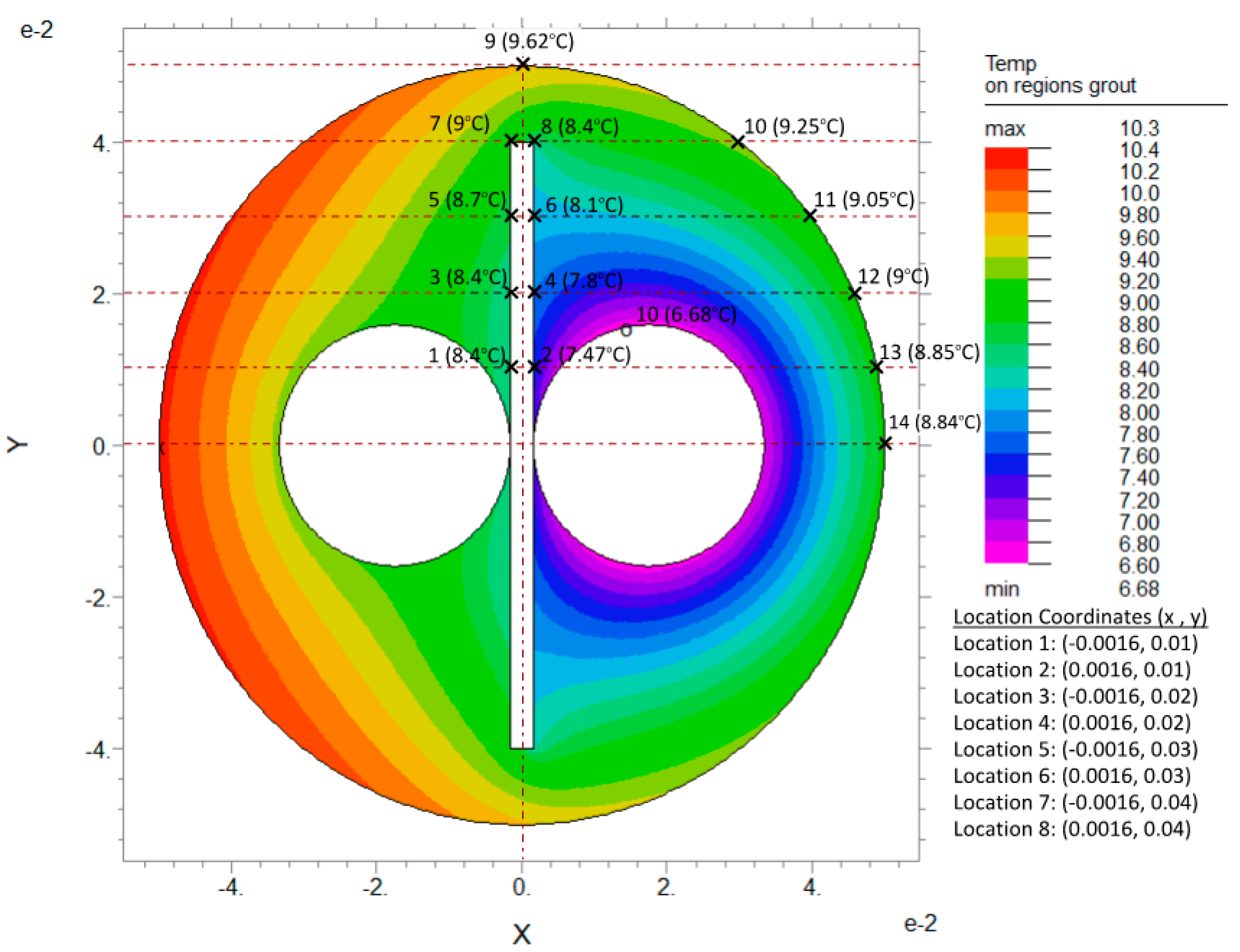

Figure 16.

Temperature distribution in grout region for U-tube BHX with barrier arrangement FSB-3PLMT, ks: 1 W/m.K, kg: 0.585 W/m.K and S: 35 mm.

Figure 16.

Temperature distribution in grout region for U-tube BHX with barrier arrangement FSB-3PLMT, ks: 1 W/m.K, kg: 0.585 W/m.K and S: 35 mm.

Figure 17.

Reduction in U-tube BHX length at Smin, for flat plate barriers at various conditions of grout & soil thermal conductivity.

Figure 17.

Reduction in U-tube BHX length at Smin, for flat plate barriers at various conditions of grout & soil thermal conductivity.

Figure 18.

Reduction in U-tube BHX length at Savg, for flat plate barriers at various conditions of grout & soil thermal conductivity.

Figure 18.

Reduction in U-tube BHX length at Savg, for flat plate barriers at various conditions of grout & soil thermal conductivity.

Figure 19.

Reduction in U-tube BHX length at Smin, for double flat plate barriers at various conditions of grout & soil thermal conductivity.

Figure 19.

Reduction in U-tube BHX length at Smin, for double flat plate barriers at various conditions of grout & soil thermal conductivity.

Figure 20.

Reduction in U-tube BHX length at Savg, for double flat plate barriers at various conditions of grout & soil thermal conductivity.

Figure 20.

Reduction in U-tube BHX length at Savg, for double flat plate barriers at various conditions of grout & soil thermal conductivity.

Figure 21.

Reduction in the BHX length for various single U- barriers; ks: 0.5 W/m.K.

Figure 21.

Reduction in the BHX length for various single U- barriers; ks: 0.5 W/m.K.

Figure 22.

Reduction in the BHX length for various single U- barriers; ks: 2 W/m.K.

Figure 22.

Reduction in the BHX length for various single U- barriers; ks: 2 W/m.K.

Figure 23.

Reduction in the BHX length for various U- barriers; ks: 0.5 W/m.K.

Figure 23.

Reduction in the BHX length for various U- barriers; ks: 0.5 W/m.K.

Figure 24.

Reduction in the BHX length for various U- barriers; ks: 2 W/m.K.

Figure 24.

Reduction in the BHX length for various U- barriers; ks: 2 W/m.K.

Figure 25.

Reduction in length for various arrangements of U-tube BHX compared to coaxial pipes; ks: 0.5 W/m.K, (a) Smin (b) Savg.

Figure 25.

Reduction in length for various arrangements of U-tube BHX compared to coaxial pipes; ks: 0.5 W/m.K, (a) Smin (b) Savg.

Figure 26.

Reduction in length for various arrangements of U-tube BHX compared to coaxial pipes; ks: 1 W/m.K, (a) Smin (b) Savg.

Figure 26.

Reduction in length for various arrangements of U-tube BHX compared to coaxial pipes; ks: 1 W/m.K, (a) Smin (b) Savg.

Figure 27.

Reduction in length for various arrangements of U-tube BHX compared to coaxial pipes; ks: 2 W/m.K, (a) Smin (b) Savg.

Figure 27.

Reduction in length for various arrangements of U-tube BHX compared to coaxial pipes; ks: 2 W/m.K, (a) Smin (b) Savg.

Figure 28.

Decision tree for the type BHX for the minimum length.

Figure 28.

Decision tree for the type BHX for the minimum length.

Table 1.

U-tube BHX model parameters.

Table 1.

U-tube BHX model parameters.

| S. No. |

Model Parameter |

Value |

Units |

| 1 |

Un-disturbed soil temperature Ts

|

15 |

°C |

| 2 |

Temperature of the outlet pipe of U-tube, Tfi

|

9 |

°C |

| 3 |

Temperature of the inlet pipe of U-tube, Tfo

|

6 |

°C |

| 4 |

Mean fluid temperature, |

7.5 |

°C |

| 5 |

Borehole Diameter, Db

|

100 |

mm |

| 6 |

Various soils thermal conductivity, ks, considered in the analysis are: |

0.5 |

W/m.K |

| 1 |

W/m.K |

| 2 |

W/m.K |

| 7 |

Various grouts thermal conductivity, kg, considered in the analysis are: |

0.585 |

W/m.K |

| 1 |

W/m.K |

| 2 |

W/m.K |

| 8 |

Various shank spacing options, S, considered in the analysis are: |

31.8 |

mm |

| 50 |

mm |

| 68.1 |

mm |

| 9 |

U-tube pipe material |

High density polyethylene (HDPE) |

- |

| 10 |

Pipe thermal conductivity [33, 34] |

0.45 |

W/m.K |

| 11 |

Pipe outer diameter, dpo [35] |

31.8 |

mm |

| 12 |

Pipe thickness, tp [35] |

2.9 |

mm |

| 13 |

Fluid (water) density [32] |

999.5 |

kg/m3

|

| 14 |

Fluid (water) dynamic viscosity [32] |

0.001418 |

kg/m.s |

| 15 |

Fluid Prandtl number [32] |

10.2768 |

- |

| 16 |

Calculated Reynolds number for fluid |

22,164 |

- |

| 17 |

Calculated Nusselt number for fluid |

174.98 |

- |

| 18 |

Calculated Convective heat transfer coefficient of fluid, h |

3,907 |

W/m2.K |

Table 2.

Validation results for FlexPDE 6.51 analysis of U-tube BHX.

Table 2.

Validation results for FlexPDE 6.51 analysis of U-tube BHX.

Table 3.

Coaxial pipes model parameters.

Table 3.

Coaxial pipes model parameters.

| S. No. |

Model Parameter |

Value |

Units |

| 1 |

Fluid temperature for estimation of borehole thermal resistance, |

6 |

°C |

| 2 |

Inlet (Outer) pipe material |

Black steel |

- |

| 3 |

Inlet (Outer) pipe thermal conductivity [33] |

43 |

W/m.K |

| 4 |

Inlet (Outer) pipe diameter (external) [51, 52] |

48.3 |

mm |

| 5 |

Inlet (Outer) pipe thickness [51, 52] |

3.68 |

mm |

| 6 |

Outlet (Inner) pipe material |

HDPE |

- |

| 7 |

Outlet (Inner) pipe thermal conductivity [33, 34] |

0.45 |

W/m.K |

| 8 |

Outlet (Inner) pipe diameter (external) [35] |

25 |

mm |

| 9 |

Outlet (Inner) pipe thickness [35] |

2.3 |

mm |

| 10 |

Thickness of insulation on outlet (inner) pipe |

3 |

mm |

| 11 |

Thermal conductivity of insulation [46] |

0.0342 |

W/m.K |

| 12 |

Thickness of uPVC protective pipe [53] |

1.5 |

mm |

| 13 |

Thermal conductivity of uPVC protective pipe [54] |

0.17 |

W/m.K |

| 14 |

Inlet fluid (Water at 6⁰C): |

|

|

| |

Density [32] |

999.6 |

kg/m3

|

| |

|

0.001483 |

kg/m.s |

| |

|

10.8029 |

|

| |

|

55.66 |

|

| |

|

7,355 |

|

| |

|

0.0378 |

|

| |

|

4,634 |

W/m2.K |

| 15 |

|

|

|

| |

|

999.3 |

kg/m3

|

| |

|

0.00135 |

kg/m.s |

| |

|

9.7507 |

|

| |

|

23,276 |

|

| |

|

215.94 |

|

| |

|

6,173 |

W/m2.K |

Table 4.

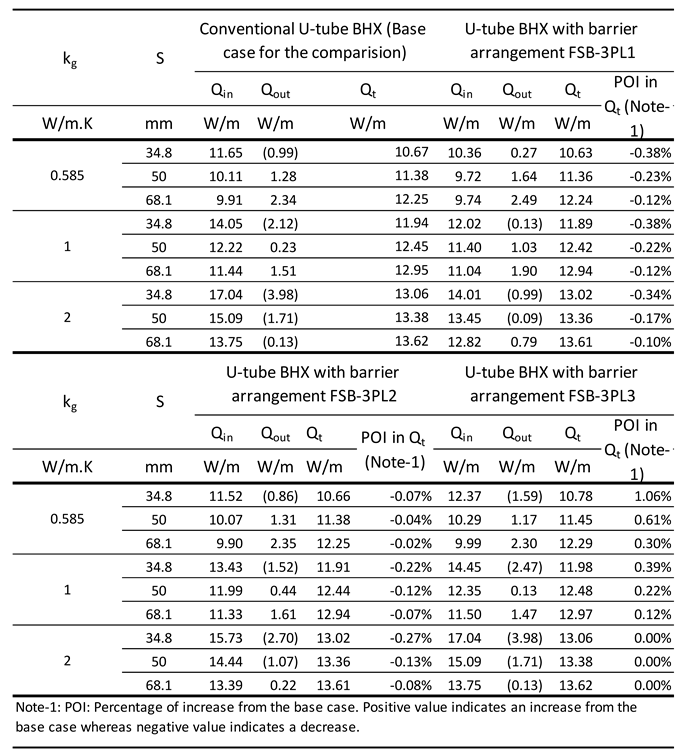

Comparison of U-tube BHX heat transfer for plastic barrier arrangements FSB-3PL1, FSB-3PL2 and FSB-3PL3; ks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 4.

Comparison of U-tube BHX heat transfer for plastic barrier arrangements FSB-3PL1, FSB-3PL2 and FSB-3PL3; ks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 5.

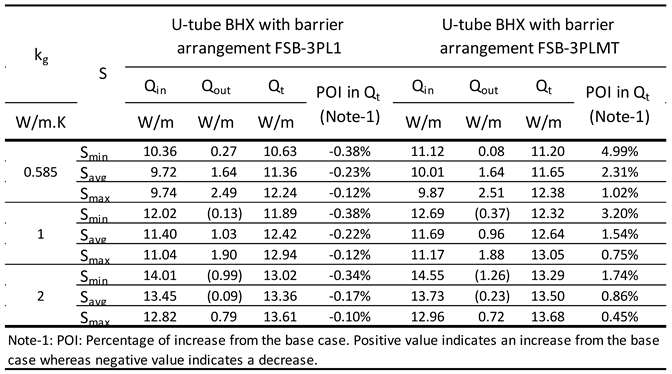

Comparison of heat transfer for barrier arrangement FSB-3PL1 and FSB-3PLMT; ks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 5.

Comparison of heat transfer for barrier arrangement FSB-3PL1 and FSB-3PLMT; ks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 6.

U-tube BHX heat transfer for flat plate metallic barriers FSB-3SS and FSB-3BR, ks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 6.

U-tube BHX heat transfer for flat plate metallic barriers FSB-3SS and FSB-3BR, ks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 7.

Absolute and percentage reduction in length for U-tube BHX with barrier arrangement FSB-3BR.

Table 7.

Absolute and percentage reduction in length for U-tube BHX with barrier arrangement FSB-3BR.

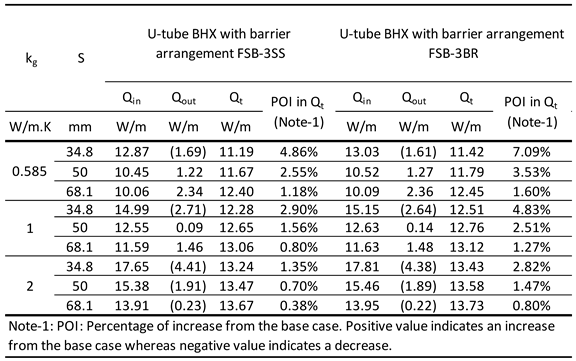

Table 8.

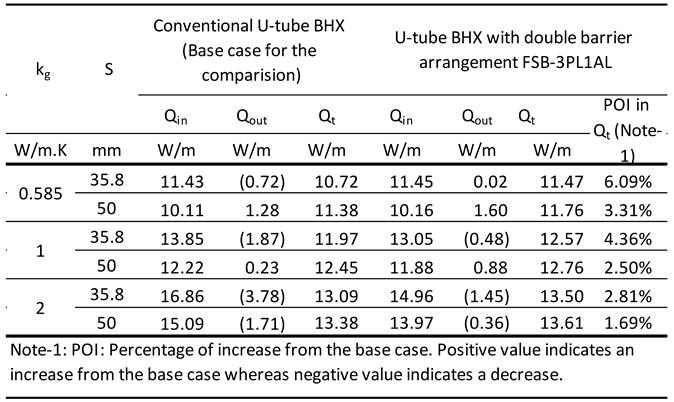

Comparison of heat transfer from U-tube BHX with barrier arrangement FSB-3PL1AL, ks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 8.

Comparison of heat transfer from U-tube BHX with barrier arrangement FSB-3PL1AL, ks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 9.

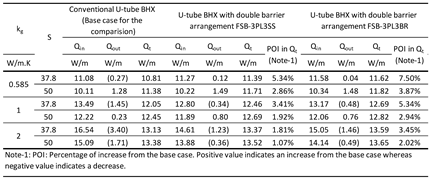

Comparison of heat transfer from U-tube BHX with double barrier arrangements FSB-3PL3SS FSB-3PL3BR; ks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 9.

Comparison of heat transfer from U-tube BHX with double barrier arrangements FSB-3PL3SS FSB-3PL3BR; ks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 10.

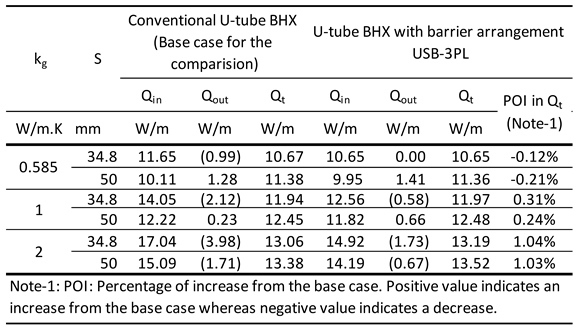

Comparison of U-tube BHX heat transfer for plastic barrier arrangements USB-3PL; ks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 10.

Comparison of U-tube BHX heat transfer for plastic barrier arrangements USB-3PL; ks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 11.

Comparison of heat transfer from U-tube BHX with barrier arrangement FSB-3PL1 and FSB-3PLMT; ks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 11.

Comparison of heat transfer from U-tube BHX with barrier arrangement FSB-3PL1 and FSB-3PLMT; ks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 12.

U-tube BHX heat transfer for metallic U-barriers USB-3SS USB-3BR ks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 12.

U-tube BHX heat transfer for metallic U-barriers USB-3SS USB-3BR ks: 1 W/m.K.

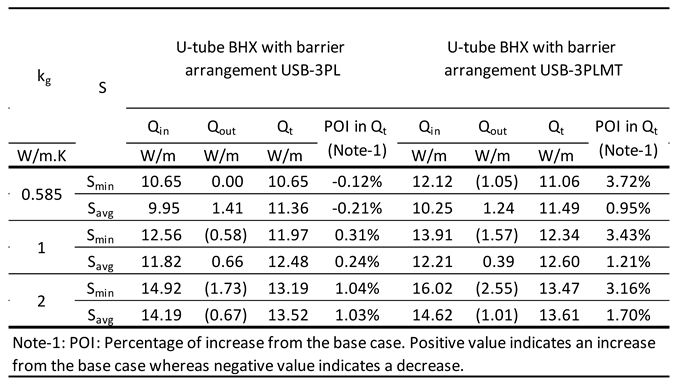

Table 13.

Comparison heat transfer for U-tube BHX with double barrier arrangement USB-3PL1AL; ks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 13.

Comparison heat transfer for U-tube BHX with double barrier arrangement USB-3PL1AL; ks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 14.

U-tube BHX heat transfer for double barrier arrangements USB-3PL3SS USB-3PL3BRks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 14.

U-tube BHX heat transfer for double barrier arrangements USB-3PL3SS USB-3PL3BRks: 1 W/m.K.

Table 15.

The comparative summary of the results of the analysis by Al-Chalabi [6] and the relevant results of this study.

Table 15.

The comparative summary of the results of the analysis by Al-Chalabi [6] and the relevant results of this study.