1. Introduction

The puma (

Puma concolor) is a mammal of the felid family, with 32 subspecies classified into six phylogeographic groups based on genomic analysis [

1,

2,

3]. Among these groups,

Puma concolor capricornensis,

Puma concolor concolor,

Puma concolor cabrerae, and

Puma concolor puma are found in South America;

Puma concolor cougar in North America; and

Puma concolor costaricensis in Central America [

1]. The puma is considered the second-largest feline in the Americas and the largest of the puma genus [

4] and can be found from Canada to the south of South America, excluding some regions of Chile and the Caribbean islands [

5,

6]. This feline inhabits tropical and subtropical humid forests, temperate forests, mountainous areas, swamps, as well as arid or cold regions, demonstrating its ability to adapt to various environments, including those near agricultural and anthropized areas [

4,

6].

The body mass of pumas ranges from 22 to 74 kg, with females being smaller than males [

5]. Both males and females are solitary and are active during crepuscular and nocturnal hours [

4,

5,

7]. Pumas are known for their agility and can jump to heights exceeding 5 meters [

5]. Sexual maturity is reached after 24 months and their lifespan typically ranges from 8 to 10 years, although they can live up to 13 years [

3].

The species is classified as least concern globally by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List [

2]. In Brazil, pumas are found in all biomes but face threats such as habitat loss and fragmentation due to agricultural expansion, roadkill, persecution for predation, and fires [

3,

5,

6].

The stifle joint of domestic felines is considered a complex joint, both anatomically and functionally, consisting of the medial and lateral femorotibial, and femoropatellar joints that form three communicating compartments [

8,

9]. Although the stifle joint of wild felines shares several characteristics observed in domestic cats, others are specific to each species [

10]. Some anatomical, radiological, and histological studies have been carried out on the stifle joint of

Puma concolor [

10,

11,

12], but evaluations using more advanced imaging exams are lacking. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the stifle joints of pumas, using digital radiography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Selection

The methodology used in the present study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee for the Use of Animals (CEUA - no. 0179/2022) and the National Environmental and Wildlife Bureau (SISBIO - 84129-2). Hind limbs from eight pumas (Puma concolor) were used, including three males and five females, two young, and six adults, with body masses ranging from 24 to 51 kg (mean 38.41 kg ± 10.28). Except for one puma from a zoo, all hind limbs were obtained from roadkill animals. The hind limbs were harvested by disarticulation at the hip joint, placed in plastic bags, and stored in a −20°C freezer for preservation until imaging exams.

2.2. Imaging Studies

Radiographs of the stifle joints (n=16) were taken in the craniocaudal and mediolateral views with a digital X-ray machine (NEOVet, Sedecal). Exposure parameters were set to 60 kVp and 8 mAs, with a focus-film distance of 100 cm.

CT scans were performed on a 16-channel scanner (SOMATOM Emotion, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with parameters set a 130 kVp, 116 mA, and 0.8 mm slice thickness. Cross-sectional images were obtained from the distal portion of the femur to the proximal portion of the tibia. Multiplanar (dorsal and sagittal) and

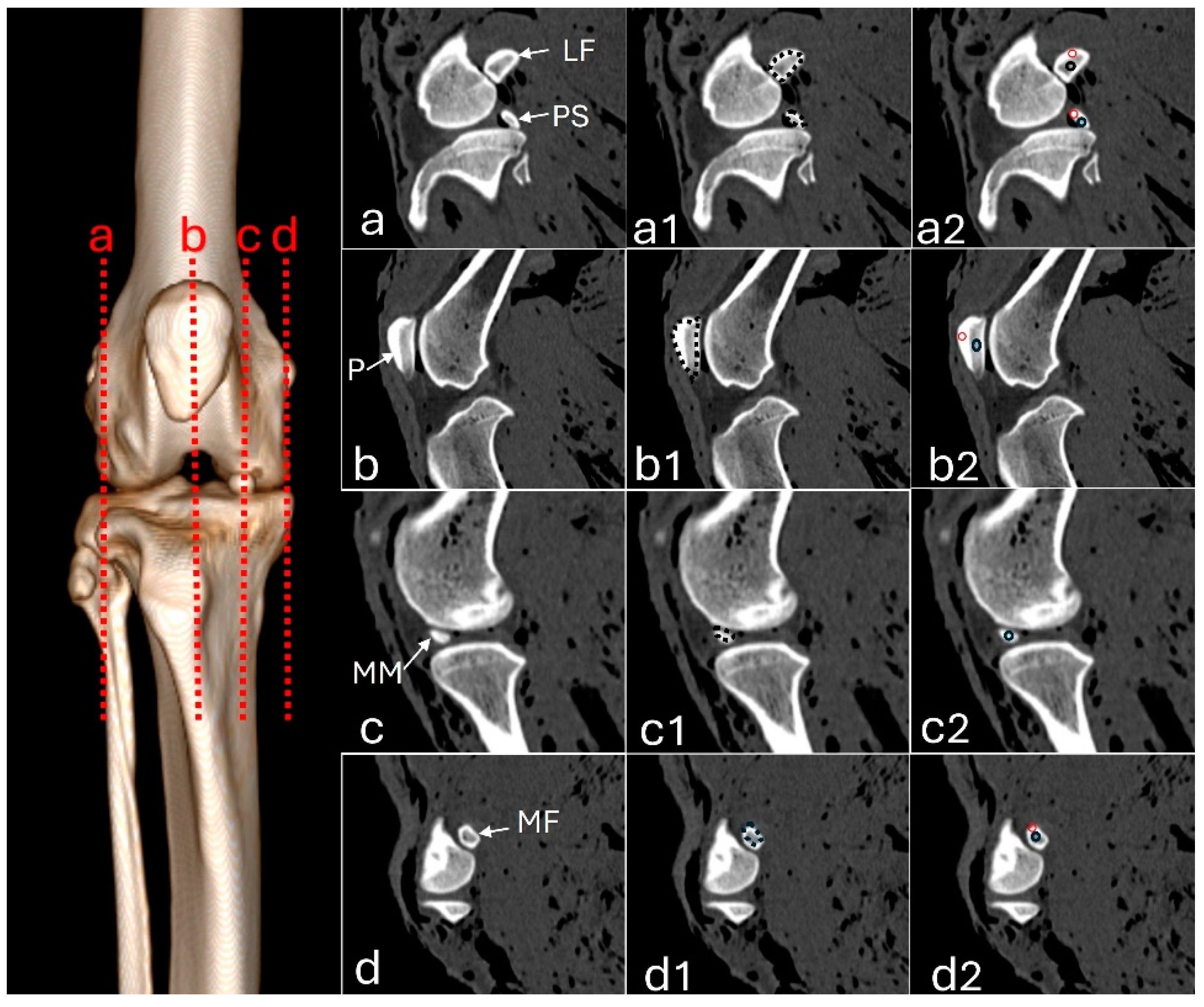

3D reconstruction images were evaluated using RadiAnt DICOM Viewer software (Medixant, Poznan, Poland). In the sagittal slice, the areas of the patella, medial and lateral fabellae (sesamoid bones located in the head of the gastrocnemius muscle), and the sesamoid of the popliteus muscle were measured (

Figure 1). Additionally, the Hounsfield Units (HU) were measured in each region of interest (ROI), which included one point in the compact bone area and another in the trabecular bone. If present, meniscal mineralization was identified based on its position in the femorotibial joint and its density measured in HU (

Figure 1).

Magnetic resonance imaging (sagittal and dorsal sections) was performed on the stifles of one animal randomly selected using 7 Tesla equipment (Magnetom 7T, Siemens Healthineers – GhMb). Sequences trialed for sagittal, transversal, and dorsal planes included 2D T2-weighted, 3D-DESS (double echo steady-state), 3D T2 SPACE (Sampling Perfection with Application optimized Contrast using different flip angle Evolution), and 3D FLASH (fast low-angle shot).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The normality of the data measurements was verified using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Based on the distribution, the unpaired t-test and Mann-Whitney test were used to compare the variables between the stifles and among sesamoids. A significance level of p < 0.05 was adopted. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA).

3. Results

Imaging exams confirmed that the two animals were young because growth plates were visible. Also, four animals had fractures: two in the left femur, one in the left fibula, and one in the left fibula and both femur bones.

3.1. Stifle Joint Description

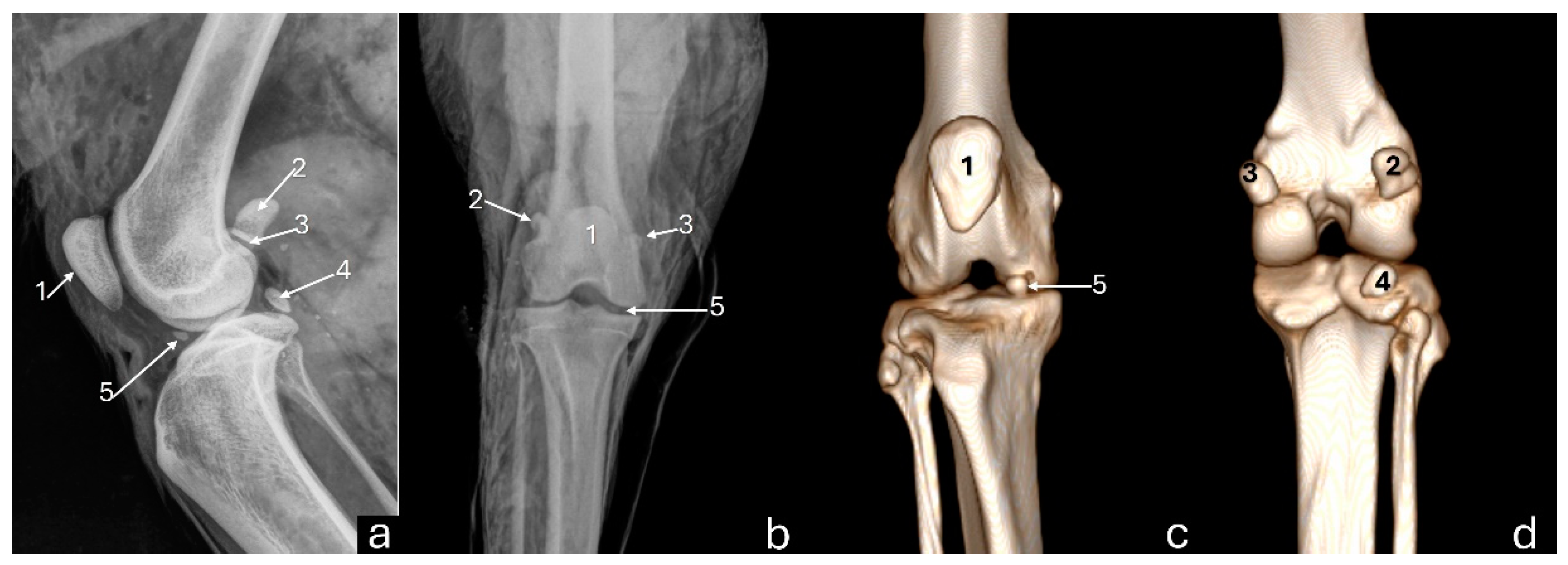

On the mediolateral radiographic view (

Figure 2a), the patella had a triangular shape with a wider base than the apex, positioned in the trochlear groove. The femoral condyles had a convex surface without overlap, with the lateral condyle larger than the medial condyle. The articular surface of the tibia had a convex appearance. The fabellae and sesamoid of the popliteal muscle were identified. An intra-articular radiopaque structure consistent with partial meniscus mineralization was observed in the stifles of three adults and one young animal. On the craniocaudal radiographic view (

Figure 2b), well-defined and convex femoral condyles on the articular surface were visualized, with the lateral condyle larger than the medial one. The patella was oval and positioned in the trochlear groove. The extensor fossa was identified on the lateral condyle. The surface of the lateral and medial tibial condyles had a slightly convex appearance, with the lateral one being larger. The intercondylar eminence was clearly defined, showing two intercondylar tubercles, with the lateral one larger than the medial one, and a central intercondylar area. The lateral and medial fabellae were visualized as rounded radiopaque structures in the epicondylar region of the lateral and medial condyles, respectively. The lateral fabella was larger than the medial one. The head of the fibula was articulated with the tibia. In the medial compartment of the femorotibial joint, a radiopaque structure was seen, compatible with meniscal mineralization in the same four animals.

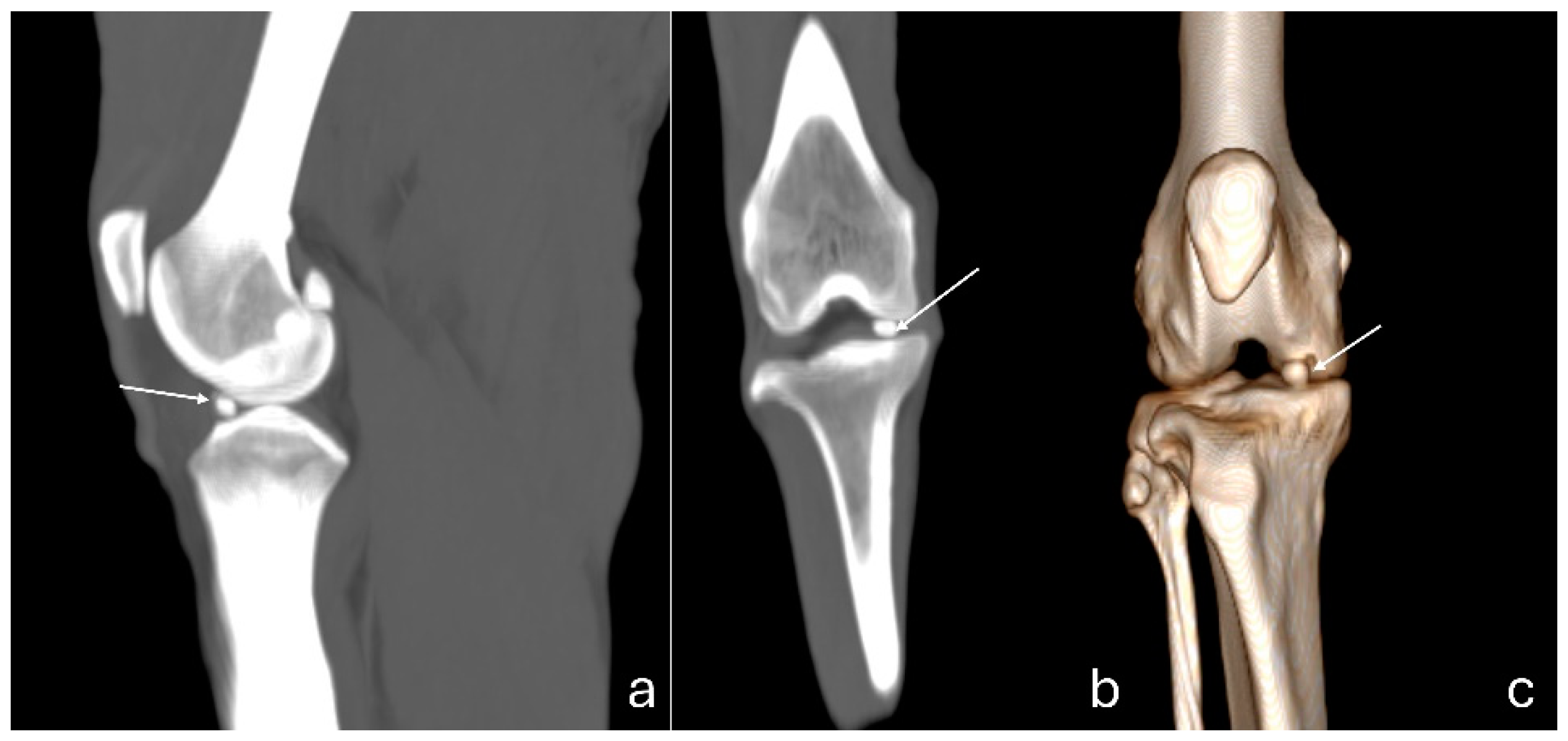

The 3D reconstruction of CT images (Figure 2c) revealed, in a cranial view, the patella as a raindrop-shaped structure with a wider base than the apex, positioned in the symmetrical trochlear groove. Meniscal mineralization was identified in the stifles of the same four animals as a hyperdense portion in the medial compartment. The caudal and lateral views displayed the lateral and medial fabellae in the epicondylar region of the lateral and medial condyles, respectively, with the lateral one being larger (Figure 2d). Other bone structures showed similar patterns as seen in radiographic images. Multiplanar and cross-sectional images allowed identification of the patella, infrapatellar fat, cranial cruciate ligament (from the caudal portion of the femur to the cranial area of the tibia), caudal cruciate ligament (from the cranial aspect of the femur to the popliteal margin of the tibia) and meniscofemoral ligament (Figure 3). The menisci were more difficult to identify, but those with partial mineralization were easily visualized (Figure 4). The fabellae and sesamoid of the popliteal were also identified; all had a thin cortical layer.

Figure 5 displays radiographs and CT images of the stifle joint of a young puma where no meniscal mineralization is detected.

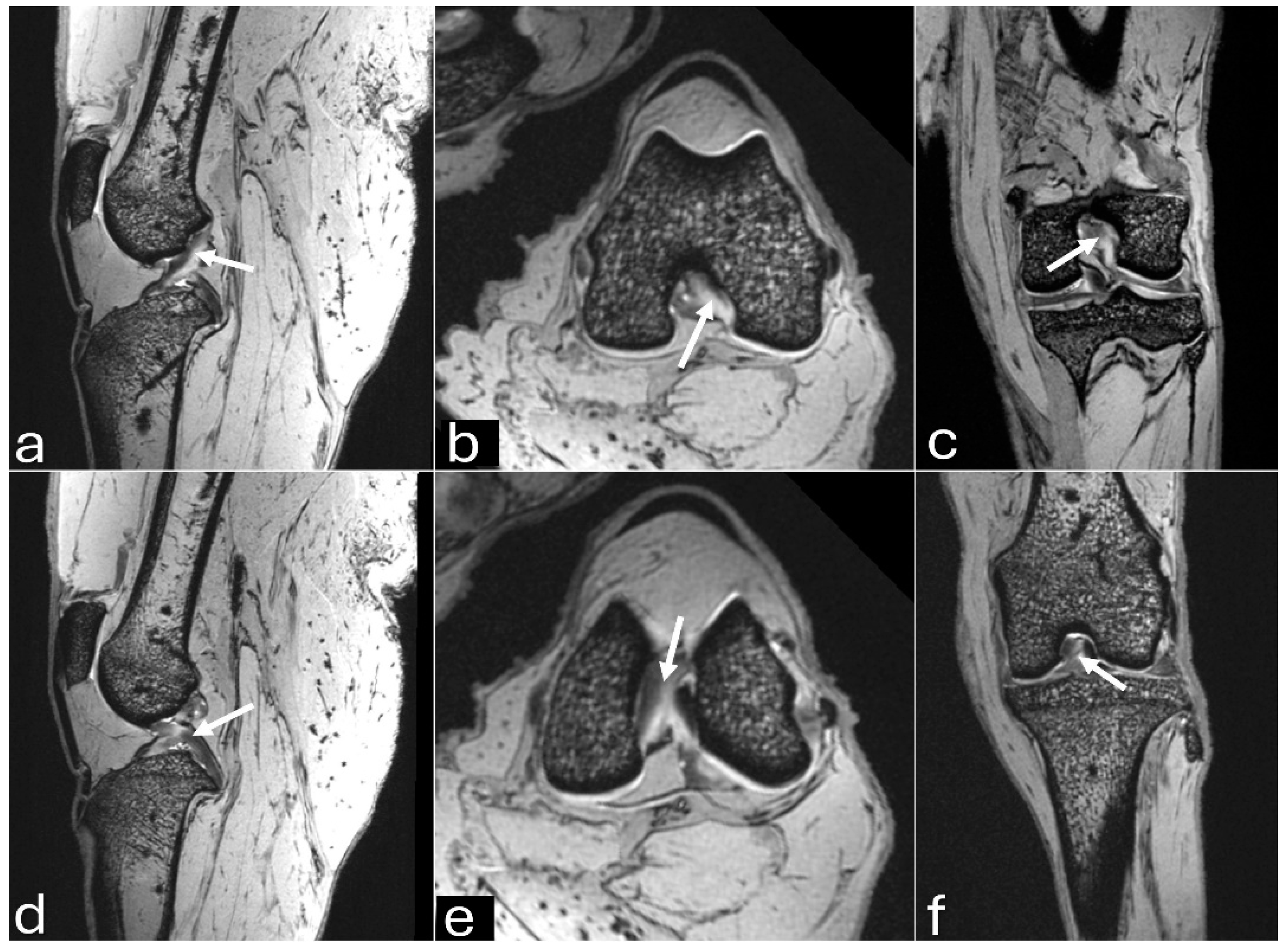

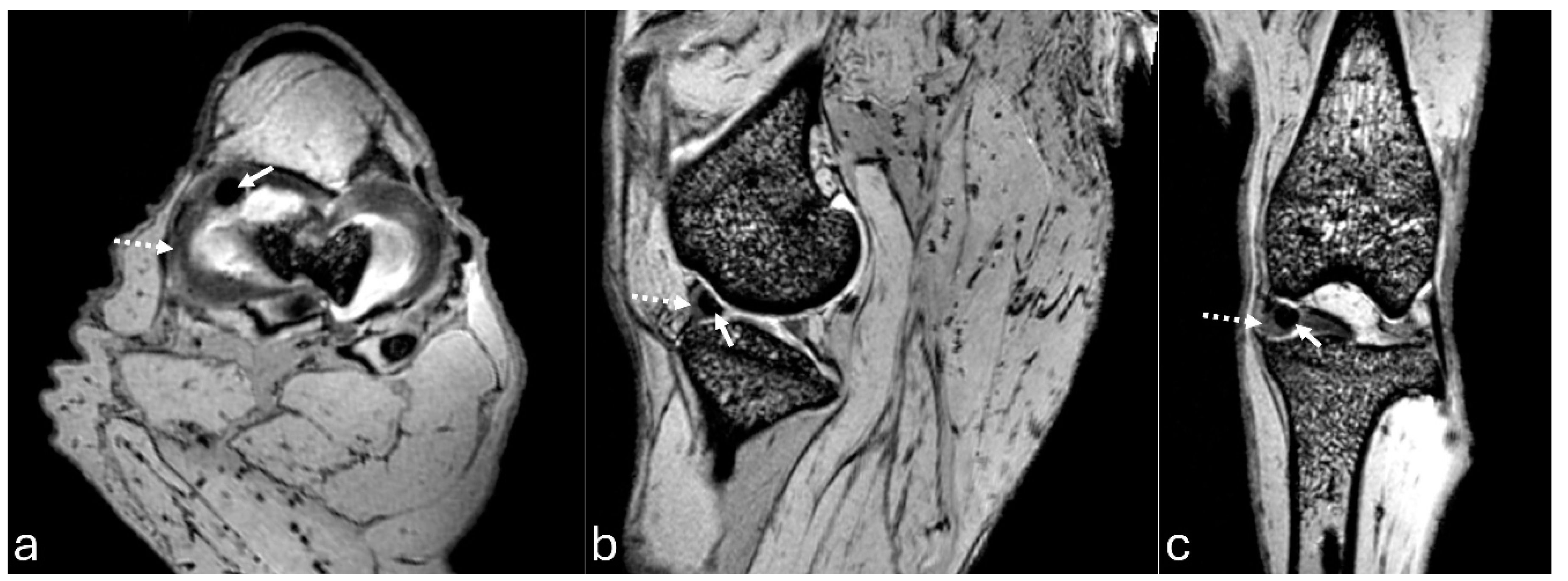

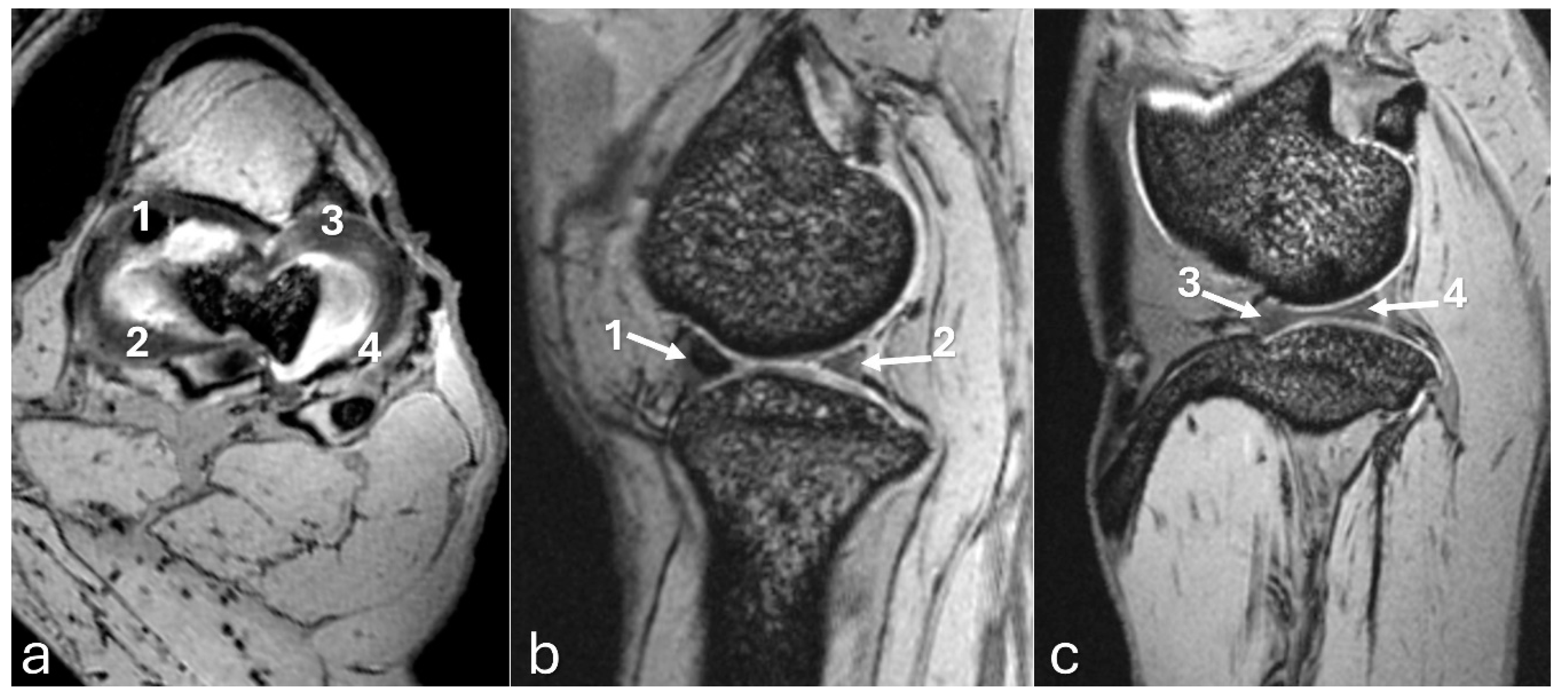

The MRI images allowed for more precise visualization of the cranial and caudal cruciate ligaments (

Figure 6), the C-type shape of both menisci on the transverse plane, and the triangular appearance on the sagittal plane, with the medial meniscus being larger than the lateral one

(Figure 7 and

Figure 8). Mineralization was easily identified in the cranial horn of the medial meniscus as a rounded structure with a

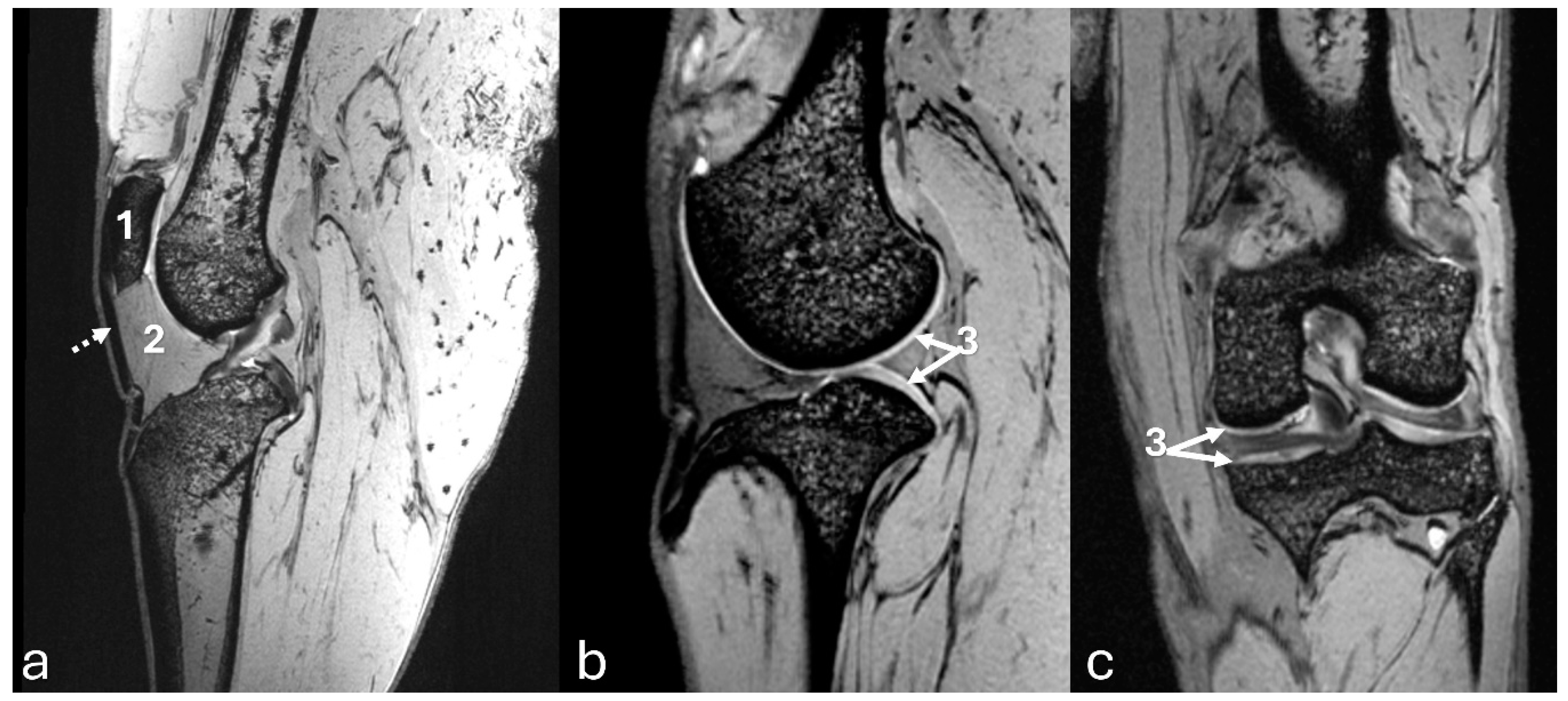

hypointense signal (3D-DESS sequence). High-resolution imaging of subchondral bone and cartilage was also visualized (

Figure 9).

No bone or cartilage lesions were found in the stifles in any of the imaging exams.

3.2. Statistical Analysis

No statistical differences were found in the tomographic measurements (cm2) and HU values of the sesamoids and medial meniscus mineralization between the right and left stifles. Therefore, the values were combined and presented as a single value in

Table 1 and

Table 2. Additionally, no differences were observed in HU values between the central trabecular bone of the patella and popliteal sesamoid, the cortical bone of the patella and lateral and medial fabella of the gastrocnemius, or the cortical bone of the patella and popliteal sesamoid (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

Imaging methods complemented each other in assessing the components of the puma's stifle joint, as certain structures like the cruciate ligaments and meniscus are not visible on plain radiographs.

The four sesamoid bones were detected in all stifle joints, i.e., the patella, the medial and lateral fabellae, and the popliteal sesamoid, as described in the domestic cat [

8]. Previous studies using two [

12] or three [

11] cadavers of

Puma concolor also verified all sesamoids. The patella appeared oval on craniocaudal radiographs and teardrop-shaped on cranial CT reconstructions, with a triangular shape on mediolateral radiographs. The appearance resembled that described by radiographic examinations and anatomic dissection of

Puma concolor, as a flattened pyramid shape craniocaudally with a broad proximal base and rounded distal apex [

11]. On CT, the patella was visualized positioned within a symmetrical trochlear groove. Symmetry of the distal femur was also noted in lions (

Panthera leo), suggesting a trend in cursorial carnivores [

13]. HU values indicated density differences between the cortical and central bone of the patella. However, cortical bone density of the patella was similar to the cortical bone of the other sesamoids.

The lateral (0.77 cm2) and medial (0.48 cm2) fabellae were easily visualized in all imaging methods, with the lateral fabella approximately 37.7% larger in size than the medial fabella, consistent with findings in other studies on

Puma concolor [

11,

12]. In domestic cats, the lateral fabella is ossified and visible on radiographs, whereas the medial fabella is often not visualized, being in these cases histologically formed of fibrocartilage [

8,

14]. The popliteal sesamoid was most clearly visible in the mediolateral radiographic view and easily identifiable through CT reconstruction. It was the smallest of the sesamoids (0.22 cm

2). In domestic cats, this sesamoid articulates with the lateral condyle of the tibia [

15] and may fail to ossify [

16]. A study on three

Puma concolor specimens found that this sesamoid was embedded at the tendomuscular transition of the popliteus muscle [

11].

The meniscus and cruciate ligaments were visualized on CT and MRI, but ultra-high-field MRI (7 Tesla) allowed these structures to be observed with precision. Following FDA approval for clinical use in humans, 7 Tesla MRI has been used to diagnose meniscal injuries and changes in articular cartilage and subchondral bone due to its rapid image acquisition, high spatial resolution, and superiority in detecting early tissue changes [

17,

18]. No articular cartilage changes were observed in the stifle joint using DESS and FLASH sequences in the present study. Previous research in humans found similar sensitivity of FLASH and DESS sequences for longitudinal morphometry of stifle cartilage [

19]. Additionally, the subchondral bone showed no changes when evaluated with the T2 sequence in the present study, which is considered the most accurate for detecting this type of injury [

20].

In the stifle joints where meniscal mineralization was identified, it was recognized in all imaging modalities in the medial meniscus. A CT scan of

Panthera tigris described the meniscal mineralization as dense cortical bone surrounding a less dense stroma, similar to the structure of the patella and fabella [

10]. In the present study, the meniscal mineralization exhibited a HU range of 924-931, lower than cortical bone (HU range of 1159.375-1363.5) and higher than trabecular bone (HU range of 373.875-632.12) found in various sesamoids.

The role of meniscal mineralization is always controversial in domestic and wild felines [

10,

21,

22,

23,

24]. In wild felines, medial meniscal mineralization has been described in

Puma concolor,

Panthera tigris,

Acinonyx jubatus,

Panthera leo,

Panthera tigris,

Panthera pardus, and

Leopardus tigrinus, but it was not associated with joint degenerative processes [

10,

11,

21,

23,

25], as verified in the present study in the imaging analysis. Conversely, in domestic felines, one study attributed the presence of mineralization to degenerative joint disease [

22], and another found that cats with a ruptured cranial cruciate ligament had a higher percentage of medium and large mineralizations compared to those without rupture [

24].

In the present study, meniscal mineralization was detected in three adults and one young animal. The young animal had meniscal mineralization of a smaller size and a lower HU value than the adults. A study involving large felines suggested that meniscal ossicles mineralize with skeletal maturation and become radiographically visible around one year of age or in the last half of skeletal maturation [

10]. The absence of meniscal mineralization in a young animal could be justified by this statement, but there were three adults in which mineralization was not identified, indicating that meniscal mineralization is not a constant finding. Furthermore, a study reported that

Panthera leo,

Panthera tigris, and

Panthera leo with meniscal ossicles typically had a lateral fabella but often lacked the medial fabella of the gastrocnemius muscle [

10]. This contrasts with the present study, where all animals had all sesamoids regardless of the presence or absence of mineralized medial meniscus.

In conclusion, the descriptions of the stifle of Puma concolor in the different imaging methods contribute to understanding the species and can serve as a basis for identifying alterations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B.M.C., S.C.R. and J.P.S.; methodology, S.C.R., J.P.S., J.T.F., G.M.F. and P.H.N.S.; software, E.B.M.C., S.C.R. and J.P.S.; validation, S.C.R. and J.P.S.; investigation, E.B.M.C.; resources, E.B.M.C., K.W., J.T.F., G.M.F. and P.H.N.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.B.M.C. and S.C.R.; writing—review and editing, S.C.R. and M.M.D.G.; visualization, S.C.R., J.P.S., M.J.M. and M.M.D.G.; supervision, S.C.R. and J.P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee for the Use of Animals (CEUA - no. 0179/2022) at the School of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science, UNESP, Campus Botucatu, and the National Environmental and Wildlife Bureau (SISBIO - 84129-2).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank FINEP (Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos; Grant 01.12.0530.00), Capes (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel)—Code 001 and CNPq (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel—PQ 305813/2023-4).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Culver, M.; Johnson, W.E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; O'Brien, S.J. Genomic ancestry of the American puma (Puma concolor). J. Hered. 2000, 91(3):186-197. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, C.; Thompson, D.; Kelly, M.; Lopez-Gonzalez, C.A. 2015. Puma concolor. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T18868A97216466. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, F.C.; Lemos, F.G.; Almeida, L.B.; Campos, C.B.; Beisiegel, B.M.; Paula, R.C.; Crawshaw Junior, P.G.; Ferraz, K.M.P.M.B.; Oliveira, T.G. Puma concolor (Linnaeus, 1771). In Livro Vermelho da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçada de Extinção. Volume II – Mamíferos; ICMBio/MMA: Brasília, DF, 2018; pp.358-366.

- Prist, P.R.; Silva, M.X.; Papi, B. Carnivora Felidae. In Guia de Rastros de Mamíferos Neotropicais de Médio e Grande Porte. Fólio Digital: São Paulo, 2020; pp.30-67.

- Cheida, C.C.; Nakano-Oliveira, E.; Fusco-Costa, R.; Rocha-Mendes, F.; Quadros, J. Ordem Carnivora. In Mamíferos do Brasil; Reis, N.R., Peracchi, A.L., Pedro, W.A., Lima, I.P., Eds.; Londrina, PR, 2011; pp.235-288.

- Azevedo, F.C.; Lemos, F.G.; Almeida, L.B.; Campos, C.B.; Beisiegel, B.M.; Paula, R.C.; Crawshaw Junior, P.G.; Ferraz, K.M.P.M.B.; Oliveira, T.G. Avaliação do risco de extinção da onça-parda Puma concolor (Linnaeus, 1771) no Brasil. Biodiversidade Brasil. 2013, 3(1):107–121.

- Arsznov, B.M.; Sakai, S.T. Pride diaries: sex, brain size and sociality in the African lion (Panthera leo) and cougar (Puma concolor). Brain Behav. Evol. 2012, 79(4):275-289. [CrossRef]

- Voss, K.; Langley-Hobbs, S.J.; Montavon, P.M. Stifle joint. In Feline Orthopedic Surgery and Musculoskeletal Disease; Montavon, P.M., Voss, K., Langley-Hobbs, S.J., Eds.; Saunders Elsevier: Edinburgh, 2009; pp.475-490.

- Agnello, K.A. Cranial cruciate ligament tear. In Comparative Veterinary Anatomy: a Clinical Approach; Orsini, J.A., Grenager, N.S., de Lahunta, A., Eds.; India: Academic Press Elsevier, 2022; pp.486-493.

- Walker, M.; Phalan, D.; Jensen, J.; Johnson, J.; Drew, M.; Samii, V.; Henry, G.; McCauley, J. Meniscal ossicles in large non-domestic cats. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound. 2002, 43(3):249-254. [CrossRef]

- Cervený, C.; Páral, V. Sesamoid bones of the knee joint of the Puma concolor. Acta Vet. Bmo. 1995, 64:79·82. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, J.I.; Zapata, C. Bone description of the Andean puma (Puma concolor): I. appendicular skeleton. Rev. Inv. Vet. Perú. 2017, 28(4):1047-1054. [CrossRef]

- Janis, C.M.; Shoshitaishvili, B.; Kambic, R.; Figueirido, B. On their knees: distal femur asymmetry in ungulates and its relationship to body size and locomotion. J. Vert. Paleontol. 2012, 32(2):433–445. [CrossRef]

- Langley-Hobbs, S.J. The patella, fabellae and popliteal sesamoids. In BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Fracture Repair and Management; Gemmill, T.J., Clements, D.N., Eds.; BSAVA: Gloucester, 2016; pp.353-356.

- Murray, C.; Beck, C. Femoral fracture. In Comparative Veterinary Anatomy: a Clinical Approach; Orsini, J.A., Grenager, N.S., de Lahunta, A., Eds.; Academic Press Elsevier: India, 2022; pp.469-485.

- Muhlbauer, M.C.; Kneller, S.K. Musculoskeleton. In Radiography of the Dog and Cat: Guide to Making and Interpreting. John Wiley & Sons: Iowa, 2013; pp.123-145.

- Menon, R.G.; Chang, G.; Regatte, R.R. The emerging role of 7 Tesla MRI in musculoskeletal imaging. Curr. Radiol. Rep. 2018, 6(26):1-10. [CrossRef]

- Kajabi, A.W.; Zbýň, Š.; Smith, J.S.; Hedayati, E.; Knutsen, K.; Tollefson, L.V.; Homan, M.; Abbasguliyev, H.; Takahashi, T.; Metzger, G.J.; LaPrade, R.F.; Ellermann, J.M. Seven tesla knee MRI T2*-mapping detects intrasubstance meniscus degeneration in patients with posterior root tears. Radiol. Adv. 2024, 1(1):umae005. [CrossRef]

- Wirth, W.; Nevitt, M.; Hellio Le Graverand, M.P.; Benichou, O.; Dreher, D.; Davies, R.Y.; Lee, J.; Picha, K.; Gimona, A.; Maschek, S.; Hudelmaier, M.; Eckstein, F.; OAI investigators. Sensitivity to change of cartilage morphometry using coronal FLASH, sagittal DESS, and coronal MPR DESS protocols--comparative data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI). Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010, 18(4):547-554. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.B.; Camanho, G.L. MRI evaluation of knee cartilage. Rev. Bras. Ortop. 2015, 45(4):340-346. [CrossRef]

- Ganey, T.M.; Ogden, J.A.; Abou-Madi, N.; Colville, B.; Zdyziarski, J.M.; Olsen, J.H. Meniscal ossification. II. The normal pattern in the tiger knee. Skeletal Radiol. 1994, 23(3):173-179. [CrossRef]

- Freire, M.; Brown, J.; Robertson, I.D.; Pease, A.P.; Hash, J.; Hunter, S.; Simpson, W.; Thomson Sumrell, A.; Lascelles, B.D. Meniscal mineralization in domestic cats. Vet. Surg. 2010, 39(5):545-552. [CrossRef]

- Rahal, S.C.; Fillipi, M.G.; Mamprim, M.J.; Oliveira, H.S.; Teixeira, C.R.; Teixeira, R.H.; Monteiro, F.O. Meniscal mineralisation in little spotted cats. BMC Vet. Res. 2013, 9:50. [CrossRef]

- Voss, K.; Karli, P.; Montavon, P.M.; Geyer, H. Association of mineralisations in the stifle joint of domestic cats with degenerative joint disease and cranial cruciate ligament pathology. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2017, 19(1):27-35. [CrossRef]

- Kirberger, R.M.; Groenewald, H.B.; Wagner, W.M. A radiological study of the sesamoid bones and os meniscus of the cheetah (Acinonyxjubatus). Vet. Comp. Orthop. Traumatol. 2000, 13(4):172-177. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Sagittal computed tomography images of an adult puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). (a) Lateral fabella (LF) and popliteal sesamoid (PS); (a1) outlining of the sesamoids for area measurement (dashed line), (a2) region of interest (ROI) of the compact bone and trabecular area for measuring Hounsfield Units (HU). (b) Patella (P), (b1) area measurement, (b2) ROIs. (c) Medial meniscus (MM), (c1) area measurement, (c2) ROIs. (d1) Medial fabella (MF), (d1) area measurement, (d2) ROIs.

Figure 1.

Sagittal computed tomography images of an adult puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). (a) Lateral fabella (LF) and popliteal sesamoid (PS); (a1) outlining of the sesamoids for area measurement (dashed line), (a2) region of interest (ROI) of the compact bone and trabecular area for measuring Hounsfield Units (HU). (b) Patella (P), (b1) area measurement, (b2) ROIs. (c) Medial meniscus (MM), (c1) area measurement, (c2) ROIs. (d1) Medial fabella (MF), (d1) area measurement, (d2) ROIs.

Figure 2.

Radiographs in mediolateral (a) and craniocaudal (b) views, and 3D reconstruction computed tomography images in cranial (c) and caudal (d) views of an adult puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). 1 - patella, 2 - lateral fabella, 3 - medial fabella, 4 - popliteal sesamoid, 5 - mineralization of the medial meniscus.

Figure 2.

Radiographs in mediolateral (a) and craniocaudal (b) views, and 3D reconstruction computed tomography images in cranial (c) and caudal (d) views of an adult puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). 1 - patella, 2 - lateral fabella, 3 - medial fabella, 4 - popliteal sesamoid, 5 - mineralization of the medial meniscus.

Figure 3.

Sagittal computed tomography images on sagittal plane of an adult puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). (a) Cranial cruciate ligament. (b) Caudal cruciate ligament. (c) Meniscofemoral ligament.

Figure 3.

Sagittal computed tomography images on sagittal plane of an adult puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). (a) Cranial cruciate ligament. (b) Caudal cruciate ligament. (c) Meniscofemoral ligament.

Figure 4.

Computed tomography images of an adult puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). Sagittal (a) and dorsal planes (b), and a cranial view of the 3D reconstruction (c). Observe mineralization of the medial meniscus (arrow).

Figure 4.

Computed tomography images of an adult puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). Sagittal (a) and dorsal planes (b), and a cranial view of the 3D reconstruction (c). Observe mineralization of the medial meniscus (arrow).

Figure 5.

Radiographs in mediolateral (a) and craniocaudal (b) views, and computed tomography images on sagittal (c) and dorsal (d) planes of a young puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). 1 - patella, 2 – femoral condyles, 3 – proximal tibial epiphysis, 4 – tibial tuberosity. Arrow – distal femoral physis. Dashed arrow – proximal tibial physis.

Figure 5.

Radiographs in mediolateral (a) and craniocaudal (b) views, and computed tomography images on sagittal (c) and dorsal (d) planes of a young puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). 1 - patella, 2 – femoral condyles, 3 – proximal tibial epiphysis, 4 – tibial tuberosity. Arrow – distal femoral physis. Dashed arrow – proximal tibial physis.

Figure 6.

3D-DESS imaging at 7-T MRI on sagittal (a, d), transversal (b, e), and dorsal (c, f) planes of an adult puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). (a, b, c) Observe the cruciate cranial ligament (arrow). (d, e, f) Note the caudal cranial ligament (arrow).

Figure 6.

3D-DESS imaging at 7-T MRI on sagittal (a, d), transversal (b, e), and dorsal (c, f) planes of an adult puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). (a, b, c) Observe the cruciate cranial ligament (arrow). (d, e, f) Note the caudal cranial ligament (arrow).

Figure 7.

3D-DESS imaging at 7-T MRI on transversal (a), sagittal (b), and dorsal (c) planes of an adult puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). Observe the medial meniscus (dashed arrow) and the mineralization of the cranial horn of the medial meniscus (arrow).

Figure 7.

3D-DESS imaging at 7-T MRI on transversal (a), sagittal (b), and dorsal (c) planes of an adult puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). Observe the medial meniscus (dashed arrow) and the mineralization of the cranial horn of the medial meniscus (arrow).

Figure 8.

3D-DESS imaging at 7-T MRI on transversal (a), and sagittal (b, c) planes of an adult puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). 1. Cranial horn of the medial meniscus. 2. Caudal horn of the medial meniscus. 3. Cranial horn of the lateral meniscus. 4. Caudal horn of the lateral meniscus. (a) Observe the C-type shape of both menisci on the transversal plane. (b, c) Note the triangle appearance of both menisci on the sagittal plane.

Figure 8.

3D-DESS imaging at 7-T MRI on transversal (a), and sagittal (b, c) planes of an adult puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). 1. Cranial horn of the medial meniscus. 2. Caudal horn of the medial meniscus. 3. Cranial horn of the lateral meniscus. 4. Caudal horn of the lateral meniscus. (a) Observe the C-type shape of both menisci on the transversal plane. (b, c) Note the triangle appearance of both menisci on the sagittal plane.

Figure 9.

3D-DESS imaging at 7-T MRI on sagittal (a, b) and dorsal (c) planes of an adult puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). (a) Observe the patella (1), infrapatellar fat pad (2), and patellar ligament (arrow). (b, c). Observe the articular cartilage on the surface of the distal femur and proximal tibia (3).

Figure 9.

3D-DESS imaging at 7-T MRI on sagittal (a, b) and dorsal (c) planes of an adult puma stifle joint (Puma concolor). (a) Observe the patella (1), infrapatellar fat pad (2), and patellar ligament (arrow). (b, c). Observe the articular cartilage on the surface of the distal femur and proximal tibia (3).

Table 1.

Tomographic measurements (cm2) in the sagittal plane of the sesamoids and medial meniscus mineralization in the right and left stifles of eight pumas (Puma concolor).

Table 1.

Tomographic measurements (cm2) in the sagittal plane of the sesamoids and medial meniscus mineralization in the right and left stifles of eight pumas (Puma concolor).

| Mensuration sites |

Mean± Standard deviation

|

Minimum |

Maximum |

IC 95% |

| Patella |

2.475 ± 0.431 |

1.700 |

3.180 |

2.246 - 2.704 |

| Medial fabella |

0.481 ± 0.126 |

0.290 |

0.700 |

0.4136 - 0.5476 |

| Lateral fabella |

0.772 ± 0.181 |

0.440 |

1.060 |

0.6752 - 0.8685 |

| Popliteal sesamoid |

0.222 ± 0.046 |

0.130 |

0.280 |

0.1972 - 0.2465 |

| Medial meniscus |

0.051 ± 0.033 |

0.010 |

0.090 |

0.02391 - 0.07859 |

Table 2.

Hounsfield Unit values measured in sesamoids (compact bone - cortical and trabecular bone - central) and meniscus mineralization in the right and left stifles of eight pumas (Puma concolor).

Table 2.

Hounsfield Unit values measured in sesamoids (compact bone - cortical and trabecular bone - central) and meniscus mineralization in the right and left stifles of eight pumas (Puma concolor).

| Mensuration sites |

|

Median |

Standard error |

Minimum |

Maximum |

IC 95% |

1º-3º Quartile |

| Patella |

Central |

643.50 |

12.91 |

508.00 |

675.00 |

595.0 - 650 |

575.3 - 661.5 |

| |

Cortical |

1202.00 |

26.25 |

1078.00 |

1408.00 |

1164 - 1276 |

1147 - 1303 |

| Medial fabella |

Central |

385.00 |

11.70 |

257.00 |

450.00 |

358.9 - 408.8 |

363.0 - 418.0 |

| |

Cortical |

1167.00 |

49.10 |

801.00 |

1481.00 |

1073 - 1282 |

1024 - 1341 |

| Lateral fabella |

Central |

437.50 |

11.86 |

344.00 |

506.00 |

406.0 - 456.6 |

402.5 - 465.0 |

| |

Cortical |

1228.00 |

57.62 |

1065.00 |

1777.00 |

1210 - 1456 |

1132 - 1777 |

| Popliteal sesamoid |

Central |

661.00 |

33.77 |

300.00 |

780.00 |

554.2 - 698.2 |

561.5 - 780.0 |

| |

Cortical |

1106.00 |

67.76 |

902.00 |

1790.00 |

1039 - 1328 |

978.5 - 1790 |

| Medial meniscus |

|

971.00 |

129.60 |

398.00 |

1354.00 |

621.1 - 1234 |

530.0 - 1354 |

Table 3.

Comparison between Hounsfield Units (trabecular bone - central and compact bone - cortical) of the patella, fabella, and popliteal sesamoid measured in the stifles of eight pumas (Puma concolor).

Table 3.

Comparison between Hounsfield Units (trabecular bone - central and compact bone - cortical) of the patella, fabella, and popliteal sesamoid measured in the stifles of eight pumas (Puma concolor).

| Variables |

P values |

Statistical test |

| Central patella X Cortical patella |

< 0.0001 |

Unpaired T |

| Central patella X Central fabella |

< 0.0001 |

Unpaired T |

| Central patella X Cortical fabella |

< 0.0001 |

Mann Whitney |

| Central patella X Central popliteal sesamoid |

0.2913 |

Mann Whitney |

| Central patella X Cortical popliteal sesamoid |

< 0.0001 |

Unpaired T |

| Cortical patella X Central fabella |

< 0.0001 |

Unpaired T |

| Cortical patella X Cortical fabella |

0.8440 |

Mann Whitney |

| Cortical patella X Central popliteal sesamoid |

< 0.0001 |

Mann Whitney |

| Cortical patella X Cortical popliteal sesamoid |

0.6131 |

Unpaired T |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).