1. Introduction

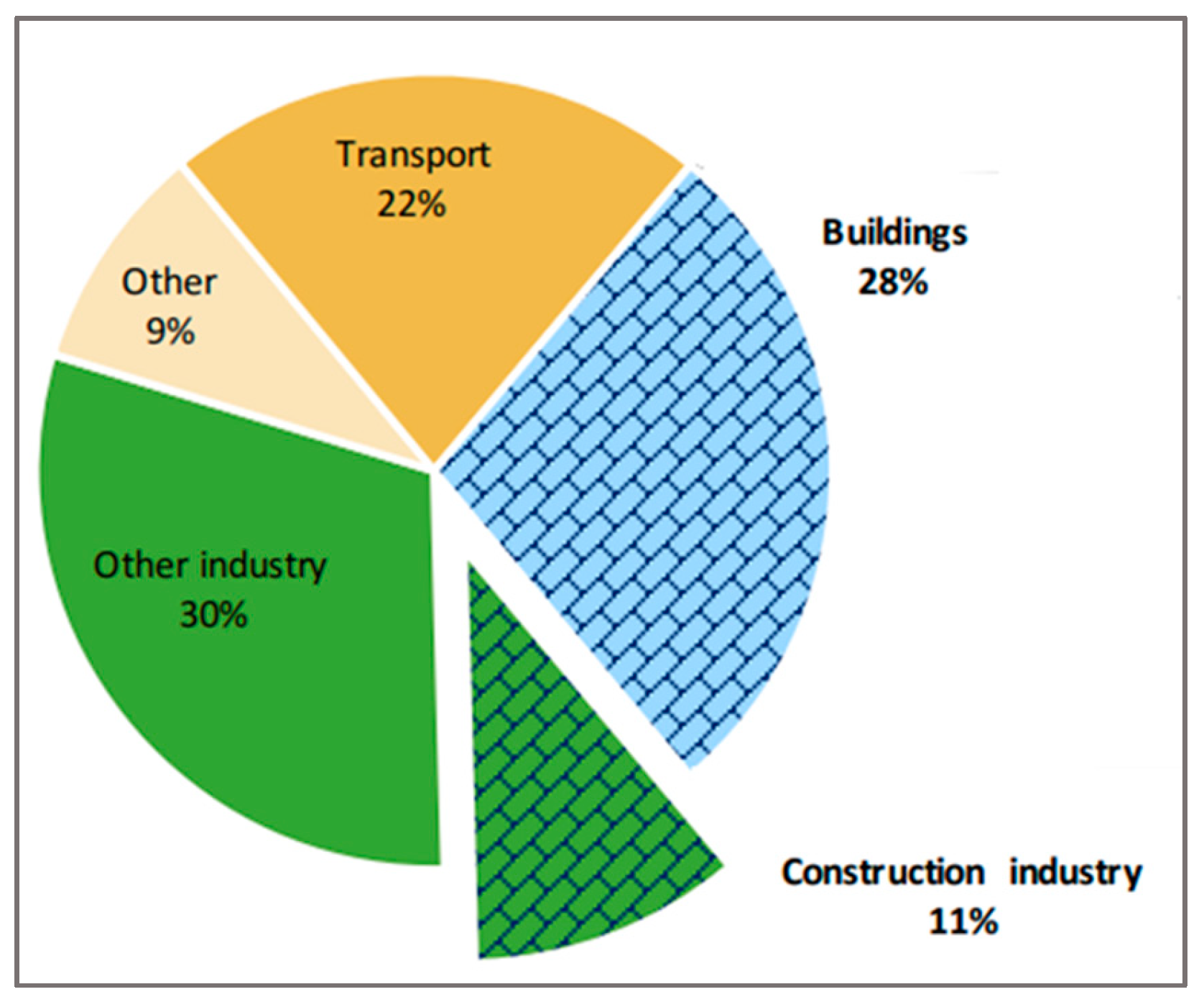

Over 35% of global energy consumption and 40% of energy-related CO

2 emissions are attributed to the building and construction industries [

1] (

Figure 1). Moreover, energy use in residential buildings is found to constitute the largest percentage of energy demand and carbon dioxide emissions [

2]. In Libya, use by existing residential buildings constitute 36% of total electricity consumption [

3]. Therefore, if the energy consumed by residential buildings could be reduced by the use of retrofit measures, this would have a considerable impact on levels of carbon dioxide released through energy production, minimising the consequences of these emissions in terms of global warming. This paper systematically reviews the relevant literature focusing on energy retrofit in residential buildings in Mediterranean countries, with a particular focus on the Libyan context.

This review aims to identify the most widely-addressed energy efficiency measures for retrofitting existing residential buildings in the Mediterranean countries, and to determine the research methods and tools adopted in current research on retrofits of existing residential buildings. Understanding the current state of energy efficiency in existing residential buildings in Mediterranean countries could help identify potential areas of intervention to improve the energy efficiency of existing residential stock in Libya.

Figure 2 shows the location of Libya and neighbouring Mediterranean countries included in the review.

2. Materials and Methods

Because the review aims to explore energy retrofit measures in residential buildings, and to determine the research methods and tools adopted in current research work in this area in the Mediterranean context, it is essential to undertake a systematic review. This method of reviewing the literature is appropriate in order to provide a critical overview of previous studies and assess their quality, as well as to identify gaps in existing knowledge. This review therefore accomplishes its aims by following the reporting checklist and flow diagram for the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews or meta-analyses (PRISMA), developed by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination to help authors improve the reporting of systematic reviews [

5]. However, since the review is performed by one author only, the method used cannot be defined as the PRISMA method.

The literature review surveys a variety of relevant sources published over the last 12 years on building energy use reduction in residential buildings in Mediterranean countries, including scholarly articles, conference proceedings, and PhD theses. To obtain a preliminary data set, a protocol comprising the inclusion criteria and analysis method was developed. Major research engines including Scopus, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar were employed to search for published articles on energy efficiency in residential buildings in Mediterranean countries including Libya. The Electronic Theses Online Service (EThOS) that is provided by the British Library was also searched for published PhD theses on energy efficiency in residential buildings in Libya.

First, the Scopus search engine was employed, using specific search terms to search the titles, abstracts, and keywords of published papers. ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, and EThOS were then also used, with the same search terms, to search for additional studies not found in the Scopus search. The search terms chosen are: TITLE-ABS-KEY((residential) AND (building*) AND (energy efficiency) AND (Libya)); TITLE-ABS-KEY((residential)AND(building*) AND (retrofit* OR renovation) AND (Libya)); TITLE-ABS-KEY ((residential) AND ( building*) AND (retrofit* OR renovation ) AND ( Mediterranean)); ( Zero ) AND (energy) AND ( residential ) AND ( building* ) AND ( retrofit OR renovation ) AND ( Libya)) TITLE-ABS-KEY (( Zero ) AND ( energy ) AND ( residential) AND ( building* ) AND ( retrofit OR renovation ) AND (Mediterranean)).

The search results from Scopus were exported and the abstracts screened to exclude irrelevant articles. Those articles from other research engines whose focus was not within the subject area, or which did not meet the inclusion criteria were also excluded. In the next step, the full text of all remaining articles found in all databases were assessed. Articles meeting the eligibility criteria were selected for the review. Lastly, the author carefully reviewed all of the included papers to extract and code the data. The review identified 44 publications of high relevance to the subject area. The results of the review are grouped into two sections: the first section presents a description of the four research themes identified from the reviewed studies; and the second section is devoted to content analysis based on those themes. Finally, the systematic review concludes with a discussion of the content analysis, and ends by identifying knowledge gaps.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to remove irrelevant articles, to include: articles with a primary focus on residential buildings; English-only manuscripts; research work on Libya and surrounding Mediterranean countries; and work presented in conferences and academic journal publications, including journals focusing on empirical work, building performance simulation, and articles devoted to methodological contributions. A diagram of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is presented in

Table 1.

2.2. Parameters for Analysis of the Literature

One of the main inclusion criteria in this research is that studies include building energy modelling (BEM) as a tool to assess and improve the energy efficiency of existing residential buildings. Thus, the review analyses each study based on four research themes: a) building energy modelling for building retrofit; b) energy model calibration for building energy retrofits; c) types of energy retrofit measures; and d) optimisation methods.

a) Building energy modelling for building retrofit

Building energy modelling is an interdisciplinary field that incorporates concepts and research from electrical and electronics engineering, civil engineering, mechanical engineering, and architecture[

6]. It can also be utilised to identify the possible sources and uses of energy in the existing buildings and to determine the best options for energy conservation measures[

7,

8]. Energy modelling and simulations, which reveal the energy-saving potentials of any energy-saving strategy, are valuable tools in retrofit design[

9].

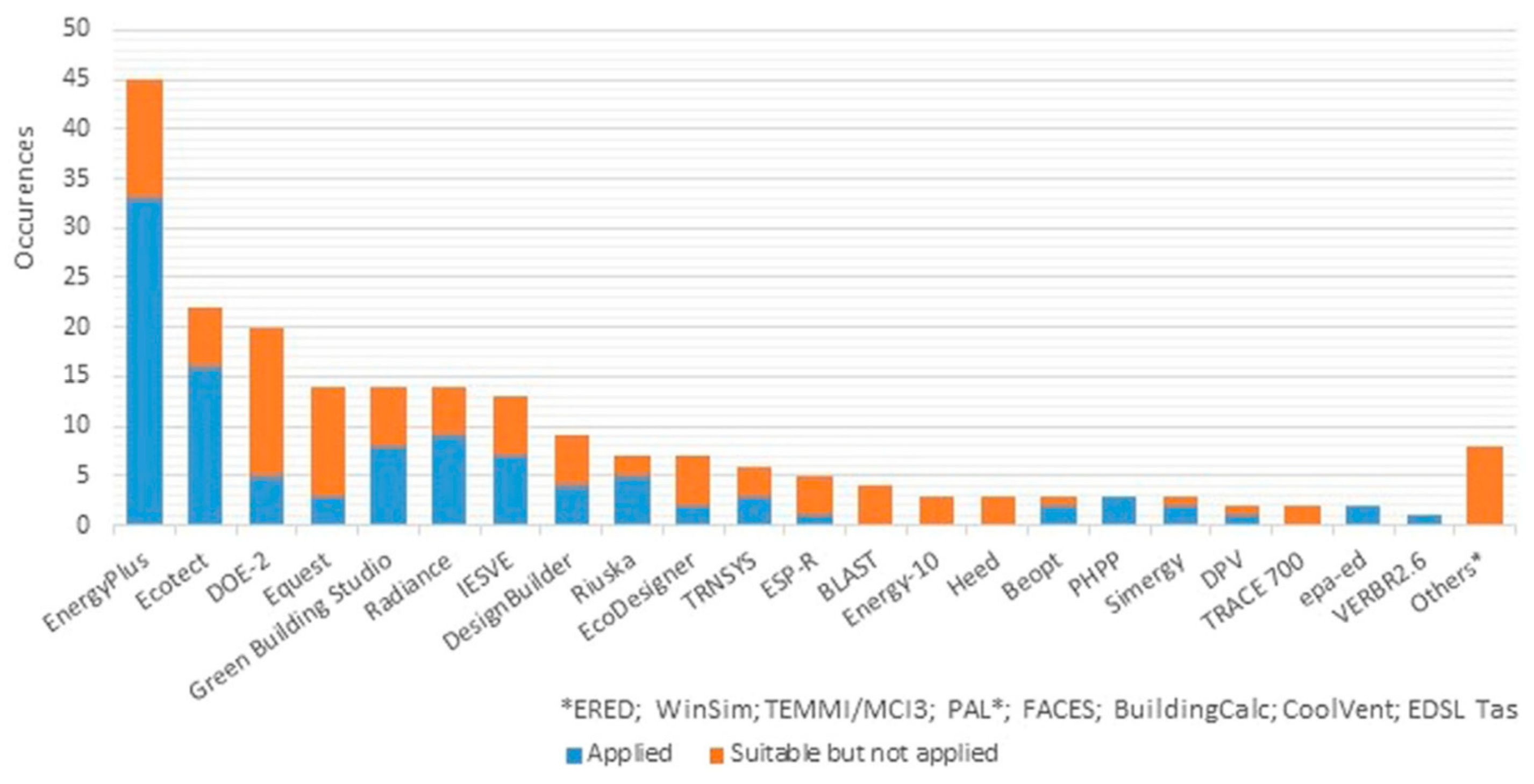

There are many building simulation software packages available currently for whole-building energy performance simulation, with different levels of complexity and response to different variables. These packages include BLAST, DOE 2, eQUEST, TRNSYS, EnergyPlus, Energy Express, EFEN, ESP-r, IDA ICE, IES, and others. Building energy modelling uses three approaches, including: standalone energy simulation tools such as EnergyPlus; integration of energy modelling software with 3D modelling software, such as Revit; and all-in-one software such as DesignBuilder. However, in many studies, energy Plus is considered the most complete simulation software tool [

7,

10,

11]. It is a whole building energy simulation program that is used to model energy consumption for heating, cooling, ventilation, and lighting. Nguyen et al in [

12]argue that EnergyPlus demonstrates a high level of reliability in predicting building energy performance. Figure 3.9 shows a summary of the energy analysis tools used in current research[

13].

Figure 3.

Energy-analysis tools used in most current research[

13].

Figure 3.

Energy-analysis tools used in most current research[

13].

b- Energy model calibration for building energy retrofits

Building energy modelling is proposed as an adequate approach to predict the thermal performance of building models, and as a procedure that assists building designers in evaluating the energy performance of a building and making necessary design changes [

6,

8,

9,

14]. Nonetheless, there is growing concern about the reliability of simulation models [

15]. Li et al in [

16] argue that in building energy models there is empirical evidence that declares noticeable discrepancies between actual and simulated building energy performance. The mismatch between actual and simulated (predicted) building performance is referred to as the 'performance gap'. This can be attributed to the assumptions made during the planning phase of energy retrofitting in existing buildings due to limited access to data, affecting the validity and dependability of energy models by these assumptions [

17]. Chong et al [

15] argue that the performance gap between measured and simulated building energy model has become increasingly evident with the adoption of smart energy meters and the Internet of Things (IoT). Consequently, to narrow the performance gap and to ensure the reliability of the simulation results, building model calibration is required. Model calibration has become an essential step in building simulation to ensure agreement between actual and simulated building energy performance, to achieve reliable results and to allow simulation estimates to more closely match actual building performance[

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. This can be achieved by matching simulation outputs with field investigation measurements using energy meters and monitoring sensors. For model calibration, both real energy consumption and zone temperature are assigned in different studies for comparison with simulation results, to ensure the simulated building models closely match the actual building, and to boost the accuracy of the building’s simulation and optimisation results [

23,

24,

25].

As part of a research project (rp-1051) initiated by ASHRAE in 2005, Reddy [

26] categorises building energy simulation calibration methodologies from existing literature into four groups as follows:

- -

Calibration based on manual iteration: a technique which involves the adjustment of inputs based on the user’s experience until the program output matches the expected data.

- -

Calibration based on graphical techniques: in this calibration process, the results are graphically represented with the use of time series and scatter plots.

- -

Calibration based on specific tests and analytical procedures: this method is based on measurement tests such as blower door tests or wall thermal transmittance (U-value). This calibration process is carried out without the use of statistical or mathematical methods.

- -

Automated methods of calibration which are based on analytical and mathematical approaches: this method is not user driven, and relies on an automated process.

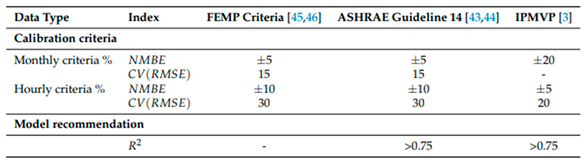

The ASHRAE 14 Guidelines assign two statistical indices to evaluate calibration accuracy: normalised mean bias error (NMBE) and coefficient of variation of the root mean squared error (CV(RMSE))[

27]. These should be within ±10% and ±30% respectively on an hourly basis or ±5% and ±15% respectively with monthly data. If the discrepancy between measured and simulated results falls within the acceptable ranges as defined by the ASHRAE 14 Guidelines, the model building is considered a calibrated model[

28]. Otherwise, the source of the discrepancy should be detected and altered such that the simulated building results match the measured ones. Table 3.3 shows the most frequently used statistical indices for the evaluation of calibration accuracy in different published energy efficiency guidance such as that of ASHRAE, FEMP, and IPMVP. After verifying the validity of the simulation by obtaining a simple error rate, the model is considered reliable for the simulation as a base case model.

Table 2.

Calibration criteria of the Federal Energy Management Program (FEMP), ASHRAE Guideline 14 and International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol (IPMVP) [

26]

.

Table 2.

Calibration criteria of the Federal Energy Management Program (FEMP), ASHRAE Guideline 14 and International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol (IPMVP) [

26]

.

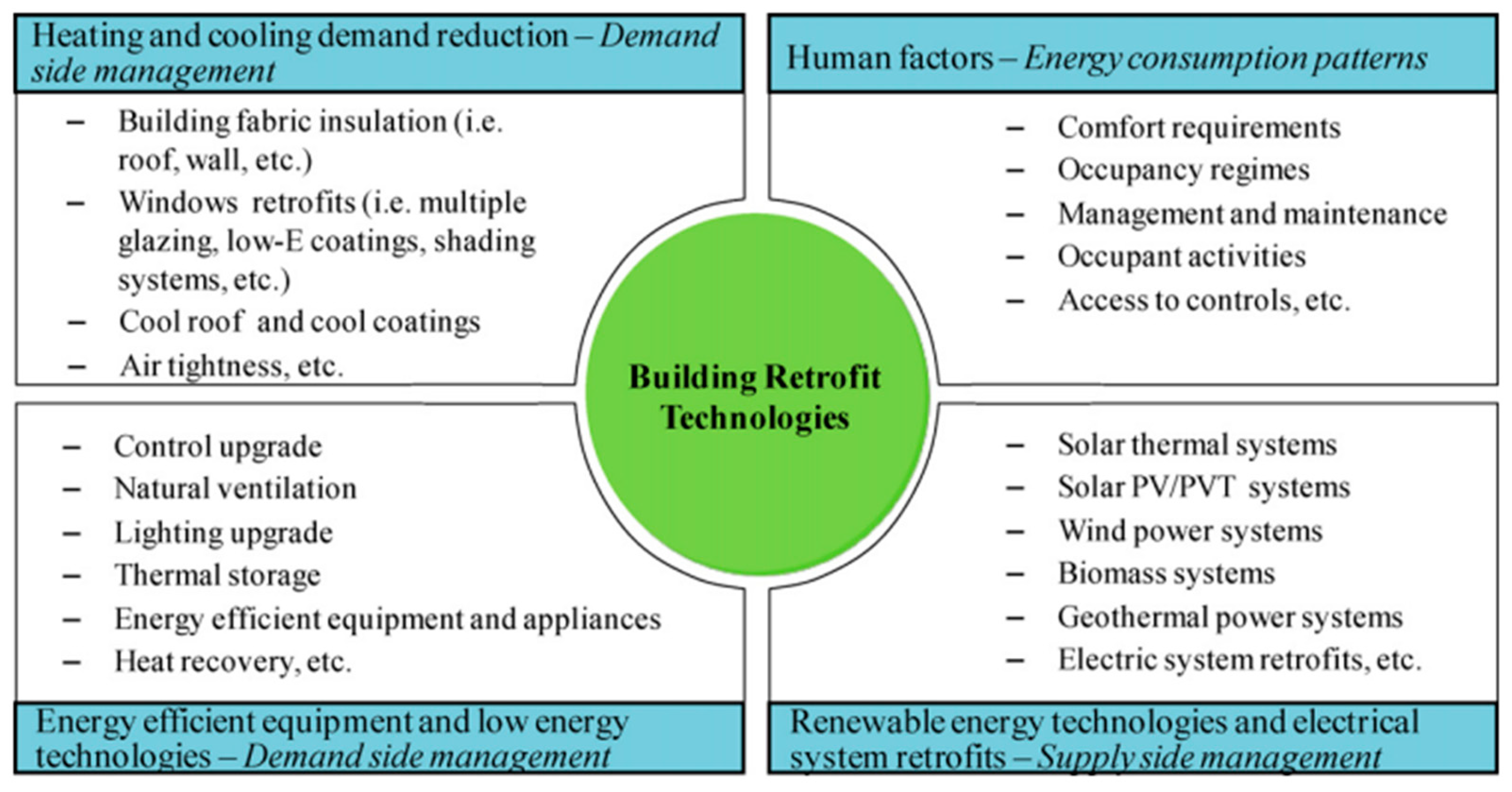

c- Type of energy retrofit measure

Energy use in residential buildings can be significantly reduced through the implementation of energy-efficiency measures or ERMs[

29]. These measures are broadly classified into three main categories, including demand side management, change in energy consumption patterns (i.e., human factors), and supply-side management [

17] (

Figure 4). Retrofit measures for demand side management include optimising the building envelope through passive measures such as adding insulation materials, using an efficient window glazing system, etc. Retrofit measures for supply-side management include the use of renewable energy such as solar photovoltaics (PV) systems. Changing energy consumption patterns involves consideration of residents’ behaviours regarding use of lighting and equipment, adjusting set point temperatures, etc. Energy- efficiency measures can be implemented individually (single measures), or for more energy saving potential can be employed in combination (combined measures) [

30].

d- Optimisation method

The term "optimisation" refers to the process of finding the optimal solution to a problem within a set of constraints [

31]. In building performance optimisation, a group of variables (x) is set according to a group of criteria, referred to as an objective function (Y), to determine the optimum solution to a problem. Single and multi-objective optimisation are two different optimisation approaches to identifying the optimal design solution [

32]. A single-objective optimisation problem is a problem that has only one objective: one single objective function of one independent variable Y = f(x). Single objective optimisation can effectively give the "optimal" solutions for a particular objective. However, the designers are not given any information on the effects of the variables to be optimised on the different design objectives. On the other hand, multi-objective optimisation gives designers detailed information for improved decisions [

33].

3. Results

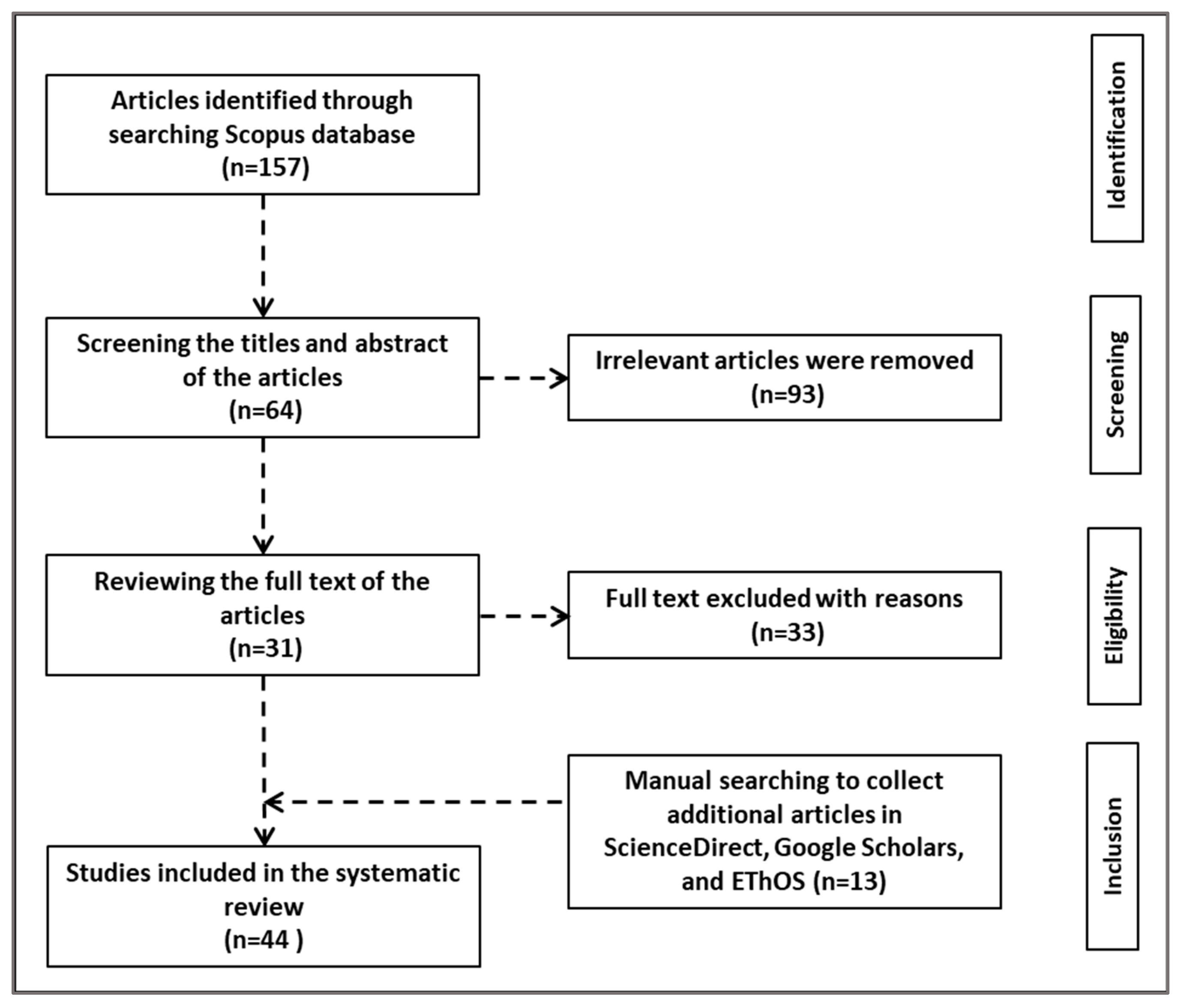

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

A preliminary search in Scopus revealed 157 studies. Following screening of the abstracts, 93 irrelevant articles were discarded. The full texts of the remaining records were reviewed to exclude articles that did not meet the eligibility criteria. A total of 33 articles were then excluded, and 31 studies were included in the systematic review. Manual searches to collect additional research via ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, and EThOS resulted in 13 further relevant papers. Thus, a total of 44 published works, including articles in 22 journals, 6 conference papers published in conference proceedings, and four PhD theses were identified and included in the systematic review. These studies were carefully reviewed and important data was extracted and analysed.

Figure 5 shows the literature selection criteria adopted in this study.

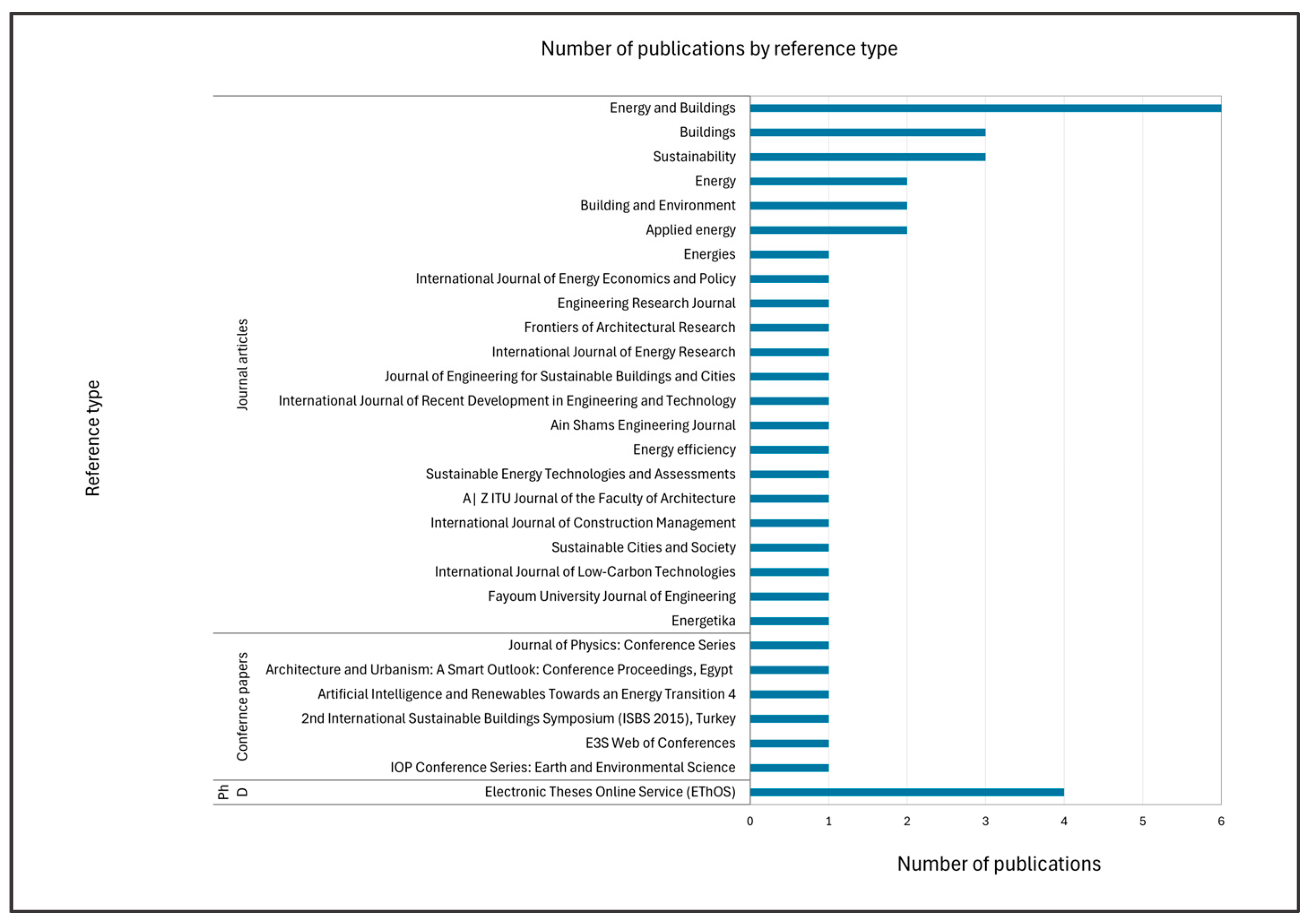

Figure 6 reports the number of included publications by reference type, which shows that this paper has a good quality literature basis on which to conduct the review.

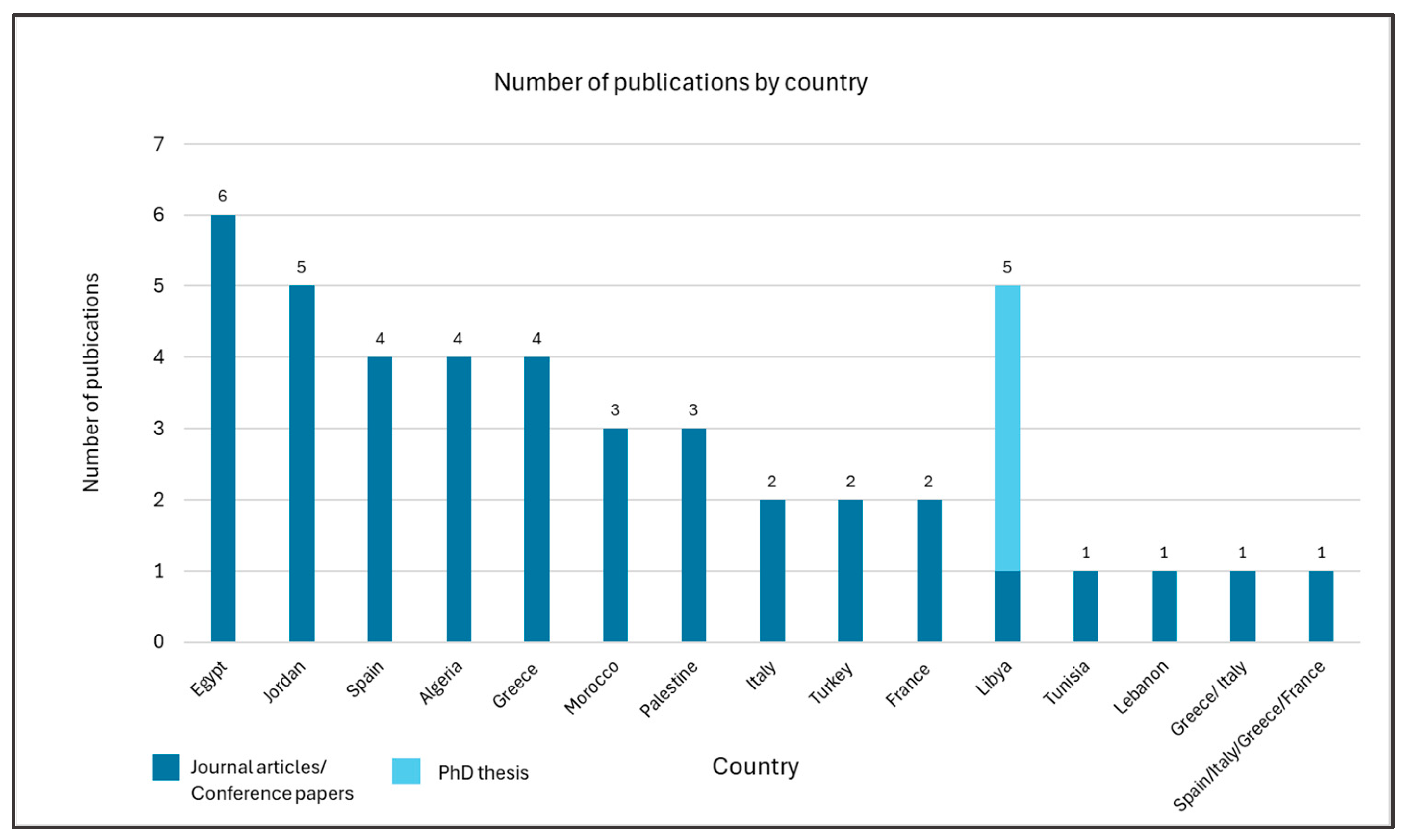

The final screening process as shown in

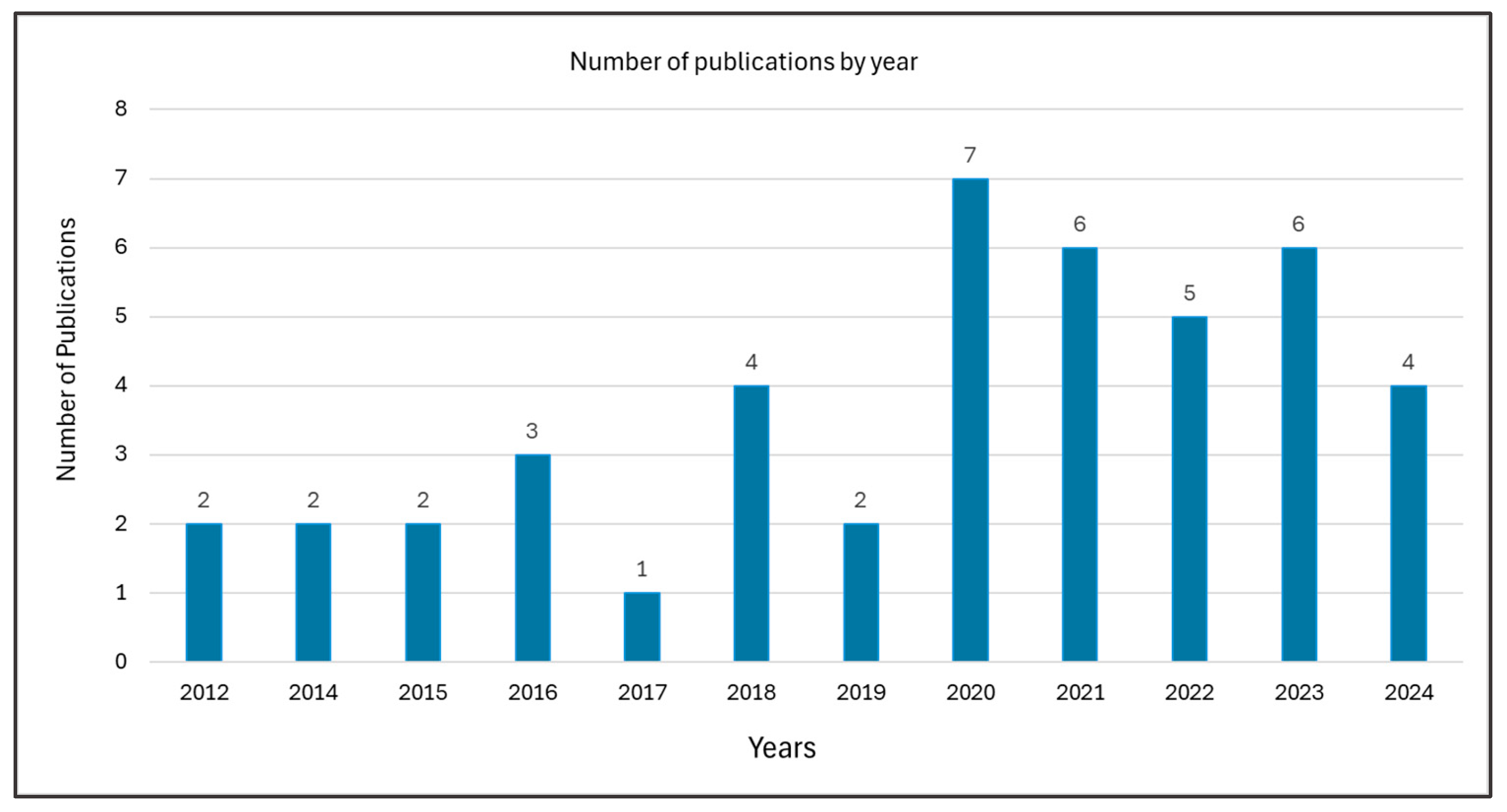

Figure 7, included 44 relevant studies. There are 6 studies conducted in Egypt, 5 studies in Jordan, 5 studies in Libya, 4 studies in Spain, 4 studies in Algeria, 4 studies in Greece, 3 studies in Morocco, 3 studies in Palestine, 2 studies in Italy, 2 studies in Turkey, 2 studies in France, one study in Tunisia, one study in Lebanon, and 2 multi-country studies. An analysis of publication year shows that 70% of the studies were published during the last five years, while the remaining studies were published up to eight years earlier than this (

Figure 8). This pattern suggests that energy retrofitting is currently an interesting and widely pursued research area in the region. This is due to the growing significance of energy retrofitting in residential buildings. However, there are few studies on retrofitting existing residential stock in Libya, as only one published paper was found in relation to this[

34], while the PhD theses produced in the Libyan context are dedicated to setting a framework for designing new energy efficient residential buildings for Libya.

3.2. Results of Analysis of Review Parameters

3.2.1. Energy Model Calibration for Building Energy Retrofits

Table 3 lists the types of software used to create the 3D model for case study buildings and building energy simulations employed in each study. The majority of the studies, at around 62%, employ an all-in-one building energy modelling method, and mostly with DesignBuilder software, which is the most established and advanced user interfaces with EnergyPlus. The other studies, at about 38%, incorporate 3D modelling software and building energy simulation tools. This result supports previous reviews, which state that EnergyPlus is considered the most complete and reliable software as a simulation tool [

13].

3.2.2. Energy Model Calibration for Building Energy Retrofits

The majority of the studies reviewed do not report calibrating the building model to ensure that the models closely represent the actual buildings [

35,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

44,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

78] (

Table 4). Some studies employ a proposed model for conducting the simulation without clarifying how reliable these models are [

39,

42,

79]. Therefore, These models cannot be trusted as representative of the actual buildings, and the optimisation results cannot be taken as a guide for improving the actual buildings.

Some studies employ electricity bills for model calibration. For example, Abdelrady et al. [

43] compare the simulation results with the actual energy consumption of an apartment building using the electricity bills of the third-floor apartment, to represent the average power consumption of all apartments within the building. The average error and the correlation coefficient are used as indices to calculate the discrepancy between the actual and simulated model, and both indices are found to be within the acceptable range[

43]. Ali [

74]. employs energy bills to estimate the annual energy consumption of the actual building and compare this to the annual energy consumption of the simulated building model.

Other studies employ data from previous studies or government reports to calibrate the case study building model. For instance, The study in [

59] was carried out to retrofit a house located in France. However, due to gaps in governmental reports on utility bills and consumer electricity bills, the space heat conditioning requirements obtained in this study are compared with data provided in previous research with a similar house[

59]. Another study compares the baseline energy consumption of the building model with the total electricity consumed in the residential sector based on an annual government report[

36]. Authors in [

62]. compares the thermal loads of the model simulation results with data calculated in another study for the same building model.

Only five articles adopt model calibration using measured data data [

37,

54,

65,

68,

69]. Authors in [

24] argued that the prediction accuracy of building energy models can now be thoroughly assessed with measured data: especially with the availability of environmental and energy monitoring equipment. Bataineh and Al Rabee data [

37] measure the energy consumption data for a single day and graphically compare this with simulated data. In another study, the actual air temperature of two indoor spaces, measured for a month in the summer and a month in winter, are compared based on ASHRAE 14 calibration indices [

68]. Authors in [

69] measured the air temperature for two indoor spaces for a typical week in the summer and used this for calibration based on the approach of the U.S. Department of Energy, which uses the indices of mean bias error (MBE) and the coefficient of variation of the root mean square error (CVRMSE) to ensure the accuracy of the simulated model. Short-term monitoring is also adopted in PhD theses to calibrate the case study building model. For example, the study in[

75] employs only two weeks of indoor temperature data. In another study, one summer day’s indoor temperature data is compared graphically with the simulated data [

77]. However, for robust model calibration, and to ensure that the model represents the actual building performance over the year, data measured over a long time and in different seasons of the year are required as calibration of building performance using a short period of time could lead to discrepancies.

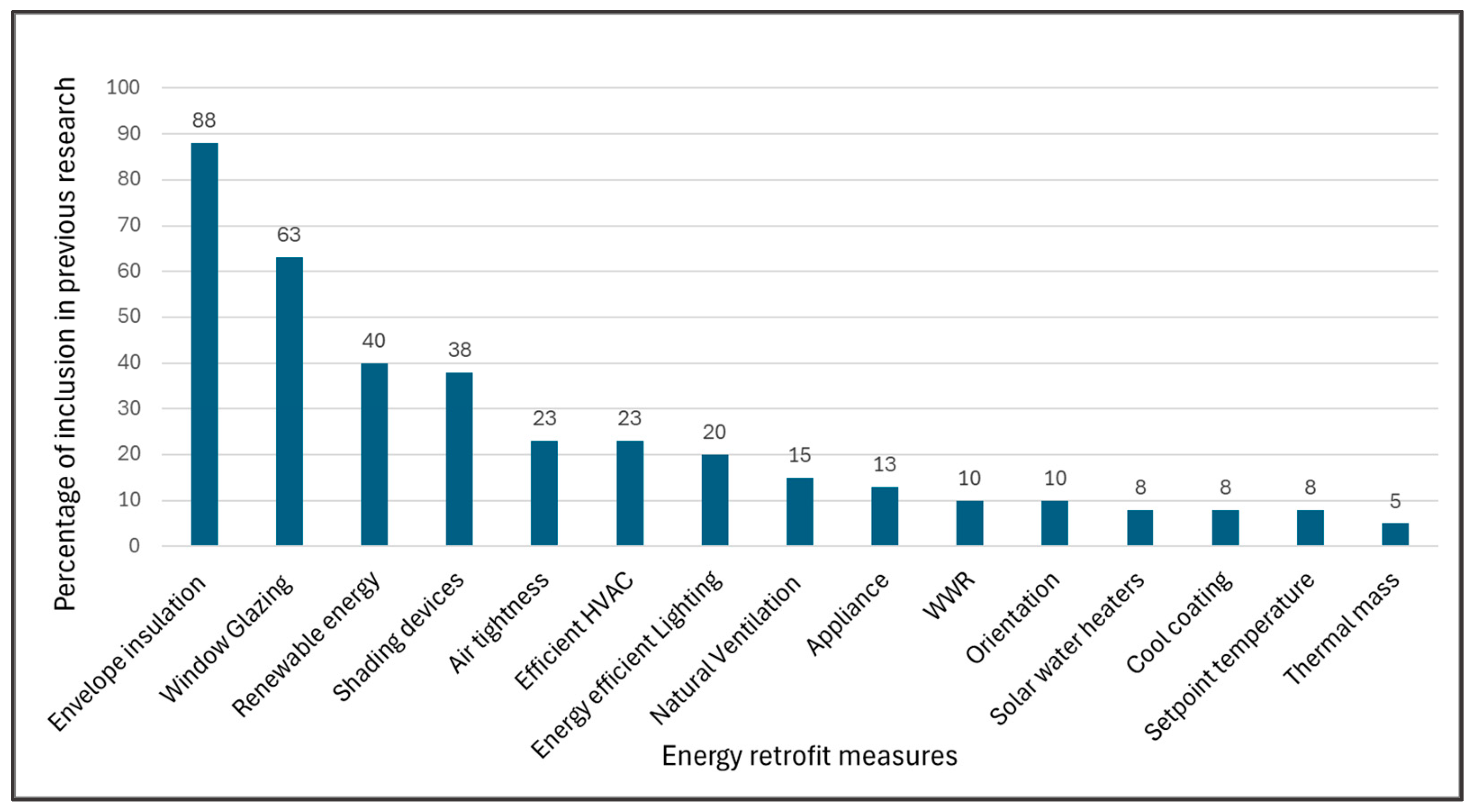

3.2.3. Types of Energy Retrofit Measure

Different passive and active ERMs were explored in the research articles, including adding envelope insulation, replacing window glazing, adding window shading, adjusting WWR, improving airtightness, boosting night-time natural ventilation, and deploying efficient HVAC systems, lighting, and appliances, as well as integrating renewable energy sources. However, passive measure had the greatest impact on energy reduction (

Table 5).

A typical two-story semi-detached house made with a reinforced concrete roof and hollow concrete block wall with no insulation located in Tripoli, Libya, was investigated using EnergyPlus simulation software with SketchUp and OpenStudio software packages [

34]. To improve the building energy efficiency of the case study building, single and combined energy efficiency measures were assessed. These include upgrading the building envelope with expanded polystyrene insulation material, upgrading the lighting system, and installation of solar water heaters and photovoltaic solar panels to cover the required energy for artificial lights. The study reveals that insulated roofs, which are responsible for the high thermal load, give the highest energy savings, followed by wall insulation, at 6.3%, and 5.7%, respectively. The study also finds that insulating the roof is more effective in reducing the cooling load than insulating the walls, which shows higher influence on reducing heating load than roof insulation. The study attributes this to the fact that during the summer, solar heat gain from the horizontal surface (roof) is higher than that gained by the vertical surface (walls). On the other hand, lower energy savings result from upgrading the single-glazed windows to double-glazed windows, at only 1.3%. Solar water heaters reduce annual demand by more than 12 %, and photovoltaic solar panels are assumed to cover 80% of the required lighting, to reduce annual consumption by 19.3 %. Combining these energy efficiency practices results in savings of more than 54%. The authors expect that this could lead to a reduction of 19% in national demand.

A study in [

74] investigates an existing dwelling (villa) in Benghazi,Libya, using DesignBuilder software. The house is built of concrete block walls, and has a reinforced concrete roof with no insulation. The monitoring and simulation study, which was carried out over a summer period, shows that cooling load is responsible for the 60% of energy consumed and that the average energy consumption of the building using mechanical cooling is nearly twice that of the building when using only natural ventilation. Moreover, the research reveals that natural ventilation alone makes it difficult for building occupants to feel comfortable. In this regard, without the use of mechanical cooling systems, the house cannot provide thermal comfort for the residents. The study’s results show that a prototype courtyard design inspired from vernacular architecture can contribute to substantial reductions in energy use. Insulating the building roof and walls achieved the highest energy savings, at 34% and 33.8% respectively, followed by improving the lighting type, and window & shading system, at 44% and 20.9% of energy saving respectively. Building orientation had a limited influence on energy saving. Combining all the measures, total energy savings of 84% were achieved.

The study in [

76] investigates thermal comfort and energy consumption in multi-story residential buildings in Darnah, Libya using TAS software. This study reveals that heat loss and gain through an uninsulated building envelope made of reinforced concrete roofs and cement block walls form the most influential factors in causing discomfort in both summer and winter. The study finds that a building envelope which is less responsive to the climatic conditions is responsible for almost 90% of heat gain. For the reasons stated above, this study therefore focuses on enhancing the walls, and roof of the building. Based on the research findings, adding insulation can help to reduce heat gain by up to 63 % and lower indoor temperatures by up to 6 degrees.

In [

53], a study is reported on a detached house in Gaza, Palestine, to determine the effect of wall thermal properties on annual energy consumption. The research uses a computerised calculator created by the author based on the mathematical model of cooling load temperature difference (CLTD) to calculate fabric heat gain and the solar heat gain factor (SHGF) to estimate heat transfer by fenestration. Ecotect software is also used to verify the findings and estimate the energy efficiency of the examined case. Plastered 200mm concrete blocks with a total U-value estimated at 2.78 w/m2.k , and single-glazed aluminium-framed windows, as the most commonly used wall materials in Gaza, are found to be less than desirable and inadequate to meet the U-value requirement of the Palestinian Energy Code, which is 1.8 w/m2.k. The study reveals that buildings with opaque wall materials and single-glazed aluminium-framed windows are inefficient in terms of energy savings. This is because the thermal transmittance (U- value) of these materials is high, resulting in substantial heat transfer to indoor spaces. Moreover, the results indicate that meeting the U-value of walls as recommended by the code would result in a reduction of 22 % in the total heating and cooling energy required to maintain comfortable conditions in the building during the year.

Authors in [

60] studied a multi-story residential building located in Italy with a reinforced concrete roof and hollow wall brick masonry, to identify the optimal retrofit measure using EnergyPlus software. The study reports on different types of retrofit measures for the building, including wall insulation, roof insulation, energy-efficient glazing, and different combinations of these strategies. The greatest impact on energy reduction was obtained by wall insulation.

Research was conducted on the impact of incorporating phase change insulation material into the building envelope of two-story house located in the Ghardaïa region, Algeria [

47]. A 3D model of the building was developed by SketchUp software, then imported into TRNSYS for energy simulation. The results show that optimising the building envelope with PCM panels can contribute to annual energy reductions by up to 36.4%, and improve indoor thermal conditions, achieving indoor temperature reductions of between 2.36° C and 4° C.

A family terraced house with a reinforced concrete roof and clay brick walls, located in Morocco, was examined using TRNSYS software to simulate several renovation scenarios under different climate types, including the Mediterranean climate [

54]. Thermal insulation is only required for the roof, based on the Moroccan Thermal Construction Regulation (RTCM). The investigation also considered the thermal insulation of slab-on-grade floors. The thermal simulations reveal that roof insulation allows for reductions in the heating and cooling load. However, slab-on-grade floor thermal insulation causes summer overheating, leading to an increase in demand for cooling. Based on the research findings, envelope insulation makes the greatest contribution to energy reduction for residential buildings in the Mediterranean climate, and shading devices and efficient glazing have less influence on energy reduction compared to insulating the envelope. Nevertheless, an insulating slab-on-grade floor is not required for the Mediterranean climate.

Based on the reviewed articles, roof and wall insulation are found to be the most influential passive measures for improving building energy efficiency. However, 95% of the articles consider petroleum-based insulation materials such as polystyrene fiberglass and polyurethane foam, while biobased materials are only investigated in two studies. One study considers the use of hemp fibres to insulate the building envelope, finding that this material achieves the same overall annual energy requirement as when using petroleum-based insulation materials[

70]. Another study applies date palm midrib fibres for envelope insulation. The study also shows that this material improves energy efficiency effectively as an equivalent to standard insulation [

42].

Figure 8 reveals the importance of passive measures in energy reduction. Upgrades to the envelope with insulation materials is an approach taken by 88% of the studies, followed by replacing window glazing, adding shading, and upgrading air tightness at 63%, 38%, and 23%, of the studies, respectively. Active retrofit measures such as energy-efficient lighting and appliances show less influence on building energy efficiency and are deployed less in existing research compared to passive retrofit measures. However, implementation of a PV system as an active retrofit measure for energy generation is investigated in 40% of the research and is found to have an important impact on meeting a building’s energy needs.

3.2.3.1. Energy Retrofit Approaches for Net Zero Energy Residential Buildings

Demand for energy worldwide is expected to increase due to population growth, the development of new cities, and the widespread use of HVAC systems[

56] [

55]. As part of the global efforts towards reducing the energy use and environmental impacts of buildings and as an urgent necessity in the construction sector to achieve energy transition, the concept of net zero energy buildings (NZEBs) has emerged[

80] [

79]. NZEBs are defined as “buildings that generate at least as much energy as they consume on an annual basis when tracked at the building site” [

81]. Authors in [

41] argue that the aim of this concept is to design highly sustainable buildings that rely on two main principles: energy conservation and energy production using renewable resources. Building energy retrofitting and refurbishment through modifications has been suggested to enhance energy performance and reduce the demand for energy[

59]. However, the most effective approach to achieving building energy efficiency is through incorporating renewable energy sources on-site [

82]. Consequently, energy-efficient optimisation employing passive measures, and active measures including the integration of renewable energy sources, form important measures to enhance building energy performance.

Several studies have been conducted on the reduction of building energy demand to reach zero energy buildings targets [

35,

41,

46,

56,

58,

59,

61,

64,

73] (

Table 6). A study was carried out to optimise a single-family detached house (villa) located in Cairo, Egypt, by integrating two strategies: energy efficiency retrofitting techniques to reduce energy demand, and renewable energy systems to generate sufficient energy for the building to meet net zero energy buildings targets [

41]. DesignBuilder software was used to passively optimise the building through the application of insulation materials, upgrading of window glazing and retrofitting of lighting systems. When all retrofitting types were combined, 22.6% energy reductions were achieved. The roof area allowed for installation of 44 PV panels angled at 30°, with electric power of 250 W each. The energy produced by the PV system was calculated manually. The findings from this study of 88.68% energy use reductions suggest that NZEBs could be met by applying these two strategies.

A study in [

35] aimed to optimise a typical house type located in Irbid-Jordan using dynamic building energy modelling (DesignBuilder) to achieve a near net zero energy building. The study utilised three optimisation stages; passive measures, active measures and integration of a photovoltaic system. The simulation results reveal that about 37.81% in energy savings can be achieved by applying both passive and active measures. The study on the photovoltaic system using PVsyst software shows that integration of a PV system could reduce the energy demand further, by up to 82.41%.

A study was conducted on a case study apartment building located in Algeria with a view to providing information for the development of a Simulink platform for retrofitting and energy transition of the existing housing stock to energy-efficient and near-zero energy buildings in Algeria [

46]. An energy simulation tool (DesignBuilder) was used to assess the influence of optimising the building envelope, including the glazing system, while renewable energy production from a hybrid energetic system including a PV system and a small wind turbine was estimated. The study reveals that the percentage of reductions after passive improvement varies between 51% and 75% for heating , while the percentage of reduction in cooling varies between 32% and 5%, and electricity demand is met at 99% through the integration of renewable energies in the retrofitting process.

A study to reduce consumption and improve thermal comfort for a terraced house was conducted in Nice, France[

58]. The study involved the implementation of passive measures, including the addition of insulation to the walls, roofs, and floors, upgrading windows, and minimising air infiltration. By employing these passive measures, the building energy demand was reduced by about 50%. To meet remaining energy needs, integrating photovoltaic panels into the building's structure as an active system was studied using PVsyst software. The results reveal that the PV system covers a substantial portion of electrical energy demand. Therefore, based on the reviewed articles, achieving targets around NZEBs is feasible for Mediterranean climates using a PV system. However, no existing research in the Libyan context has attempted to achieve net zero energy levels for Libyan housing.

Figure 8.

Use of various retrofit measures in previous research.

Figure 8.

Use of various retrofit measures in previous research.

3.2.4. Optimisation Method

With regards to the optimisation methods used, as shown in

Table 6, the majority of these studies adopt a single-objective optimisation problem (SOOP), which aims to optimise one variable at a time or multi-variants at a time against one objective function [

35,

36,

37,

39,

40,

41,

42,

53,

56,

57,

60,

63,

64,

65]. However, the multi-objective optimisation problem (MOOP), which helps in making decisions that consider trade-offs between two conflicting objectives, is adopted in only 7 articles. For example, three studies investigate the trade-off between energy saving and life-cycle cost (LCC) [

50,

62,

71]. A study in [

73] seeks to determine the optimal trade-off between summer and winter energy performance. However, despite the importance of thermal comfort investigations in building retrofits, none of the reviewed research considers the use of a simulation-based multi-objective optimisation problem to determine the trade-off between energy usage and thermal comfort, including that in the Libyan context. The multi-objective optimisation problem is also an existing feature in DesignBuilder, however, it is not employed in any of studies reviewed.

4. Research Gap

The results of this review reveal research gaps in the existing literature. Limited attention has been paid to retrofitting existing housing stock, and particularly in the context of Libya. In addition, none of the previous research reviewed here aims to achieve a net zero energy level for Libyan housing stock. Therefore, further study is needed to investigate the potential for meeting net zero energy buildings targets through the integration of a PV system for Libyan housing using the BEM tool.

Although DesignBuilder enables the modelling of solar photovoltaic power systems, none of the studies that deploy DesignBuilder for model simulation have exploited this feature to investigate the potential for meeting the building energy levels needed to achieve the NZEBs target. Consequently, meeting building energy needs and achieving NZEBs targets by integrating both passive and active hybrid retrofit approaches using DesignBuilder would be a novel methodological contribution to the existing literature.

A major weakness in the literature is represented by the credibility of the energy models, wherein most of the studies reviewed, including that on Libya, were carried out without ensuring the reliability of the energy model and rely on assumptions for their model setup, which would affect the accuracy of the simulation results. Measured data, which is essential for building model setup and for understanding the prediction accuracy of the building model, is adopted in several studies. However, the measurement of the environmental data and energy consumption in these articles covers only a short period, which could lead to discrepancies between the actual building’s energy use and the building energy model. Consequently, for robust model calibration, and to ensure that the model represents actual building performance, building monitoring over the whole year is necessary.

Model calibration on a monthly and hourly basis is also needed to ensure that the building model closely represents the actual building. In addition, measuring the total energy of the building as well as the energy used by each category across the whole year would provide important information through which the categories responsible for the greatest energy consumption could be identified and thus the appropriate energy retrofit measures determined. Further important data that, if not specified accurately, could have an impact on the accuracy of the energy model of an existing building is the thermal transmittance of the building envelope (U-value). Information about the structure and materials of the existing building envelope may not be accurate or may be unavailable. Consequently, it would be beneficial to employ on-site measurement as a current approach for evaluating the thermal properties of the existing building envelopes of different residential building types in Libya using a heat flux sensor, which would form an addition to existing literature on building energy retrofits in Libya.

Reducing energy consumption could have an impact on indoor thermal comfort. However, the trade-off between energy consumption and thermal comfort has not been comprehensively investigated in previous research, including that in the Libyan context. Consequently, the balance between energy consumption and thermal comfort needs to be investigated using a multi-objective optimisation problem. While this approach is an existing feature in DesignBuilder, none of the studies reviewed that used DesignBuilder for energy simulation employed this feature. Consequently, use of this tool would form a methodological addition to the existing knowledge of residential building retrofits in Mediterranean countries, including Libya, to find an optimal solution that achieves a trade-off between energy saving and thermal comfort.

Embodied carbon reduction in building retrofits needs to be considered. Biobased insulation materials for example are renewable, low-carbon materials and contribute to reducing the embodied carbon of the building. However, the majority of previous research, including that in the Libyan context, has deployed petroleum-based insulation materials. Consequently, further studies to investigate the effectiveness of different biobased insulation materials on energy reduction in Libyan housing stock would be an additional contribution to existing knowledge.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a systematic review was carried out to explore the existing research and knowledge gaps in published research focusing on energy retrofits in existing residential buildings located in Libya and neighbouring Mediterranean countries. Using search terms and keywords which were carefully selected to focus on the purpose of this systematic review, 44 relevant studies were found. Most of these were published in the last five years, but due to the limited number of publications within the research context, published literature dating back to 2012 was also included in the systematic review. Following the initial review, the articles were reviewed and analysed based on four themes identified in this review. Finally, the systematic review concluded with a discussion on content analysis and ended by identifying knowledge gaps and future research directions to address these.

The systematic review reveals a lack of research on retrofitting existing residential stock in Libya, in which context only one published research study was found. A simulation optimisation approach integrating both passive and active hybrid retrofit approaches to meeting NZEBs would be a novel contribution in the Libyan context. In addition, finding the optimal optimisation solution to achieve a trade-off between energy saving and thermal comfort for Libyan residential stock is also required. Embodied carbon reductions in building retrofits need to be considered. Biobased insulation materials for example are renewable, low-carbon materials and contribute to reducing the embodied carbon of the building. However, the majority of previous research, including that in the Libyan context, deploys petroleum-based insulation materials. Investigating the effectiveness of low-carbon materials such as biobased insulation materials on energy reduction in the Libyan housing stock would be an additional contribution to existing knowledge.

Some weaknesses were found in most of the studies reviewed, including that in the Libyan context, related to the credibility and reliability of the energy model. This was due to the lack or absence of measured data as needed for energy model setup and calibration. Consequently, further research with robust and detailed model calibration based on measured data is also needed to ensure the reliability of simulation results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.A.; methodology, S.A. and E.L; validation, S.A., and E.L.; formal analysis, S.A., E.L. and S.S.H; investigation, S.A.; data curation, E.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.; writing—review and editing, E.L. and S.S.H.; visualisation, S.A.; supervision, S.S.H.; project administration, E.L.; funding acquisition, S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Libyan attaché by providing the necessary funds for the research, and the funding body did not play any role in the execution of the research work.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Abergel, T.; Dean, B.; Dulac, J. Global status report 2017. International Energy Agency (IEA) for the Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction (GABC) 2017.

- Nejat, P.; Jomehzadeh, F.; Taheri, M.M.; Gohari, M.; Majid, M.Z.A. A global review of energy consumption, CO2 emissions and policy in the residential sector (with an overview of the top ten CO2 emitting countries). Renewable and sustainable energy reviews 2015, 43, 843-862. [CrossRef]

- Tawil, I.H.; Abeid, M.; Abraheem, E.B.; Alghoul, S.K.; Dekam, E.I. Review on Solar Space Heating-Cooling in Libyan Residential Buildings. Solar Energy and Sustainable Development journal 2018, 7. [CrossRef]

- Bastemur, C.; Güneş, G. Rural tourism in protected areas: a case study from Kure Mountains National Park-Turkey. Forestry Review 2013, 44, 23-30.

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group*, t. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of internal medicine 2009, 151, 264-269. [CrossRef]

- Harish, V.; Kumar, A. A review on modeling and simulation of building energy systems. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews 2016, 56, 1272-1292. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J. Energy simulation software for buildings: review and comparison. In Proceedings of International Workshop on Information Technology for Energy Applicatons-IT4Energy, Lisabon; pp. 1-12.

- Gao, H.; Koch, C.; Wu, Y. Building information modelling based building energy modelling: A review. Applied energy 2019, 238, 320-343. [CrossRef]

- Aksamija, A. Regenerative design of existing buildings for net-zero energy use. Procedia Engineering 2015, 118, 72-80. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.A.; Rasul, M.; Khan, M. Modelling and simulation of building energy consumption: a case study on an institutional building in central Queensland, Australia. 2007.

- Drury, C.B.; Lawrie, L.K.; Pedersen, C.O.; Liesen, R.J.; Fisher, D.E.; Strand, R.K.; Taylor, R.D.; Winkelmann, F.C.; Buhl, W.F.; Huang, Y.J. EnergyPlus: a new generation building energy simulation program. Proc. Renewable and Advanced Energy Systems for the 21st Century, Maui, Hawaii, April 1999. New York: ASME 1999. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.-T.; Reiter, S.; Rigo, P. A review on simulation-based optimization methods applied to building performance analysis. Applied energy 2014, 113, 1043-1058. [CrossRef]

- Sanhudo, L.; Ramos, N.M.; Martins, J.P.; Almeida, R.M.; Barreira, E.; Simões, M.L.; Cardoso, V. Building information modeling for energy retrofitting–A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 89, 249-260. [CrossRef]

- Crawley, D.B.; Lawrie, L.K.; Winkelmann, F.C.; Buhl, W.F.; Huang, Y.J.; Pedersen, C.O.; Strand, R.K.; Liesen, R.J.; Fisher, D.E.; Witte, M.J. EnergyPlus: creating a new-generation building energy simulation program. Energy and buildings 2001, 33, 319-331. [CrossRef]

- Chong, A.; Gu, Y.; Jia, H. Calibrating building energy simulation models: A review of the basics to guide future work. Energy and Buildings 2021, 253, 111533. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yang, Z.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Tang, C.; Chen, N. Why is the reliability of building simulation limited as a tool for evaluating energy conservation measures? Applied energy 2015, 159, 196-205. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Cooper, P.; Daly, D.; Ledo, L. Existing building retrofits: Methodology and state-of-the-art. Energy and buildings 2012, 55, 889-902. [CrossRef]

- Monetti, V.; Davin, E.; Fabrizio, E.; André, P.; Filippi, M. Calibration of building energy simulation models based on optimization: a case study. Energy Procedia 2015, 78, 2971-2976. [CrossRef]

- Mustafaraj, G.; Marini, D.; Costa, A.; Keane, M. Model calibration for building energy efficiency simulation. Applied Energy 2014, 130, 72-85. [CrossRef]

- Duverge, J.J.; Rajagopalan, P.; Woo, J. Calibrating the energy simulation model of an aquatic centre. 2018; pp. 683-690.

- Duverge, J.J.; Rajagopalan, P.; Woo, J. Calibrating the energy simulation model of an aquatic centre. 2018; pp. 683-690.

- Goldwasser, D.; Ball, B.L.; Farthing, A.D.; Frank, S.M.; Im, P. Advances in Calibration of Building Energy Models to Time Series Data; National Renewable Energy Lab.(NREL), Golden, CO (United States): 2018.

- Cornaro, C.; Bosco, F.; Lauria, M.; Puggioni, V.A.; De Santoli, L. Effectiveness of automatic and manual calibration of an office building energy model. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 1985. [CrossRef]

- Royapoor, M.; Roskilly, T. Building model calibration using energy and environmental data. Energy and buildings 2015, 94, 109-120. [CrossRef]

- Penna, P.; Cappelletti, F.; Gasparella, A.; Tahmasebi, F.; Mahdavi, A. Multi-stage calibration of the simulation model of a school building through short-term monitoring. Journal of Information Technology in Construction 2015, 20, 132-145.

- Reddy, T.A.; Maor, I.; Panjapornpon, C. Calibrating detailed building energy simulation programs with measured data—Part II: Application to three case study office buildings (RP-1051). Hvac&r Research 2007, 13, 243-265. [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. ASHRAE guideline 14-2002 Measurement of energy and demand savings. America: 2002.

- Fernandez Bandera, C.; Ramos Ruiz, G. Towards a new generation of building envelope calibration. Energies 2017, 10, 2102. [CrossRef]

- Stieß, I.; Dunkelberg, E. Objectives, barriers and occasions for energy efficient refurbishment by private homeowners. Journal of Cleaner Production 2013, 48, 250-259. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, E.; Steinberger, J.K.; Dupont, V.; Foxon, T.J. Combining energy efficiency measure approaches and occupancy patterns in building modelling in the UK residential context. Energy and Buildings 2016, 111, 98-108. [CrossRef]

- Huws, H.; Jankovic, L. A method for zero carbon design using multi-objective optimisation. In Proceedings of Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Zero Carbon Buildings Today and in the Future; pp. 11-12.

- Sadeghi, A.; Kazemi, H.; Samadi, M. Single and multi-objective optimization of steel moment-resisting frame buildings under vehicle impact using evolutionary algorithms. Journal of Building Pathology and Rehabilitation 2021, 6, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.Z.; Jamaluddin, H.; Ahmad, R.; Loghmanian, S.M. Comparison between multi-objective and single-objective optimization for the modeling of dynamic systems. Proceedings of the institution of mechanical engineers, part i: journal of systems and control engineering 2012, 226, 994-1005. [CrossRef]

- Alghoul, S.K.; Agha, K.R.; Zgalei, A.S.; Dekam, E.I. Energy saving measures of residential buildings in North Africa: Review and gap analysis. Int. J. Recent Dev. Eng. Technol 2018, 7, 59-77.

- Ali, H.H.; Al-Rub, F.A.A.; Shboul, B.; Al Moumani, H. Evaluation of near-net-zero-energy building strategies: A case study on residential buildings in Jordan. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy 2020, 10, 325-336. [CrossRef]

- Bataineh, K.; Alrabee, A. Improving the energy efficiency of the residential buildings in Jordan. Buildings 2018, 8, 85. [CrossRef]

- Bataineh, K.; Al Rabee, A. A cost effective approach to design of energy efficient residential buildings. Frontiers of Architectural Research 2022, 11, 297-307. [CrossRef]

- Attia, S.; Zawaydeh, S. Strategic decision making for zero energy buildings in Jordan. In Proceedings of Jordanian Architects Society Seminar.

- Albadaineh, R.W. Energy-passive residential building design in Amman, Jordan. Energetika 2022, 68. [CrossRef]

- Moraekip, E.M. Improving Energy Efficiency of Buildings Through Applying Glass Fiber Reinforced Concrete in Building's Envelopes Cladding Case Study of Residential Building in Cairo, Egypt. Fayoum University Journal of Engineering 2023, 6, 32-45.

- Adly, B.; Sabry, H.; Faggal, A.; Elrazik, M.A. Retrofit as a means for reaching net-zero energy residential housing in greater cairo. In Proceedings of Architecture and Urbanism: A Smart Outlook: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Architecture and Urban Planning, Cairo, Egypt; pp. 147-158. [CrossRef]

- Darwish, E.; Eldeeb, A.S.; Midani, M. Housing retrofit for energy efficiency: Utilizing modular date palm midribs claddings to enhance indoor thermal comfort. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 2024, 15, 102323. [CrossRef]

- Abdelrady, A.; Abdelhafez, M.H.H.; Ragab, A. Use of insulation based on nanomaterials to improve energy efficiency of residential buildings in a hot desert climate. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5266. [CrossRef]

- Nafeaa, S.; Mohamed, A.; Fatouha, M. Assessment of energy saving in residential buildings using energy efficiency measures under Cairo climatic conditions. Engineering Research Journal 2020, 166, 320-349. [CrossRef]

- Elsheikh, A.; Motawa, I.; Diab, E. Multi-objective genetic algorithm optimization model for energy efficiency of residential building envelope under different climatic conditions in Egypt. International Journal of Construction Management 2023, 23, 1244-1253. [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, K.; Ahriz, A.; Bouaziz, N. Development of a New Residential Energy Management Approach for Retrofit and Transition, Based on Hybrid Energy Sources. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4069. [CrossRef]

- Hamdani, M.; Bekkouche, S.M.E.A.; Al-Saadi, S.; Cherier, M.K.; Djeffal, R.; Zaiani, M. Judicious method of integrating phase change materials into a building envelope under Saharan climate. International Journal of Energy Research 2021, 45, 18048-18065. [CrossRef]

- Medjeldi, Z.; Kirati, A.; Dechaicha, A.; Alkama, D. Parametric design of a residential building system through solar energy potential: the case of Guelma, Algeria. In Proceedings of Journal of Physics: Conference Series; p. 042012. [CrossRef]

- Badeche, M.; Bouchahm, Y. Contribution of renewable energies in existing building retrofits. In Proceedings of Artificial Intelligence and Renewables Towards an Energy Transition 4; pp. 55-61. [CrossRef]

- Ihm, P.; Krarti, M. Design optimization of energy efficient residential buildings in Tunisia. Building and Environment 2012, 58, 81-90. [CrossRef]

- Monna, S.; Juaidi, A.; Abdallah, R.; Albatayneh, A.; Dutournie, P.; Jeguirim, M. Towards sustainable energy retrofitting, a simulation for potential energy use reduction in residential buildings in Palestine. Energies 2021, 14, 3876. [CrossRef]

- Haj Hussein, M.; Monna, S.; Abdallah, R.; Juaidi, A.; Albatayneh, A. Improving the thermal performance of building envelopes: An approach to enhancing the building energy efficiency code. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16264. [CrossRef]

- Muhaisen, A.S. Effect of wall thermal properties on the energy consumption of buildings in the Gaza strip. 2015.

- Sobhy, I.; Benhamou, B.; Brakez, A. Effect of retrofit scenarios on energy performance and indoor thermal comfort of a typical single-family house in different climates of Morocco. Journal of Engineering for Sustainable Buildings and Cities 2021, 2, 021003. [CrossRef]

- Sghiouri, H.; Mezrhab, A.; Karkri, M.; Naji, H. Shading devices optimization to enhance thermal comfort and energy performance of a residential building in Morocco. Journal of building Engineering 2018, 18, 292-302. [CrossRef]

- Abdou, N.; Mghouchi, Y.E.; Hamdaoui, S.; Asri, N.E.; Mouqallid, M. Multi-objective optimization of passive energy efficiency measures for net-zero energy building in Morocco. Building and environment 2021, 204, 108141. [CrossRef]

- Sassine, E.; Dgheim, J.; Cherif, Y.; Antczak, E. Low-energy building envelope design in Lebanese climate context: the case study of traditional Lebanese detached house. Energy efficiency 2022, 15, 56. [CrossRef]

- Nazififard, M.; Zeynali, S. Analysis of Photovoltaic Panel Integration for Achieving Net-Zero Energy in French Residential Retrofits in a Mediterranean Climate. In Proceedings of E3S Web of Conferences; p. 02006. [CrossRef]

- Kutty, N.; Barakat, D.; Khoukhi, M. A French residential retrofit toward achieving net-zero energy target in a Mediterranean climate. Buildings 2023, 13, 833. [CrossRef]

- Stazi, F.; Veglio, A.; Di Perna, C.; Munafo, P. Retrofitting using a dynamic envelope to ensure thermal comfort, energy savings and low environmental impact in Mediterranean climates. Energy and Buildings 2012, 54, 350-362. [CrossRef]

- Rosso, F.; Ciancio, V.; Dell'Olmo, J.; Salata, F. Multi-objective optimization of building retrofit in the Mediterranean climate by means of genetic algorithm application. Energy and Buildings 2020, 216, 109945. [CrossRef]

- Kitsopoulou, A.; Bellos, E.; Lykas, P.; Vrachopoulos, M.G.; Tzivanidis, C. Multi-objective evaluation of different retrofitting scenarios for a typical Greek building. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2023, 57, 103156. [CrossRef]

- Kitsopoulou, A.; Pallantzas, D.; Sammoutos, C.; Lykas, P.; Bellos, E.; Vrachopoulos, M.G.; Tzivanidis, C. A comparative investigation of building rooftop retrofit actions using an energy and computer fluid dynamics approach. Energy and Buildings 2024, 315, 114326. [CrossRef]

- Liapopoulou, E.; Theodosiou, T. Energy performance analysis and low carbon retrofit solutions for residential buildings. In Proceedings of IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; p. 012026. [CrossRef]

- Synnefa, A.; Vasilakopoulou, K.; Kyriakodis, G.-E.; Lontorfos, V.; De Masi, R.; Mastrapostoli, E.; Karlessi, T.; Santamouris, M. Minimizing the energy consumption of low income multiple housing using a holistic approach. Energy and Buildings 2017, 154, 55-71. [CrossRef]

- Mangan, S.D.; Oral, G.K. A study on determining the optimal energy retrofit strategies for an existing residential building in Turkey. A| Z ITU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture 2014, 11, 307-333.

- Pekdogan, T.; Yildizhan, H.; Ahmadi, M.H.; Sharifpur, M. Assessment of window renovation potential in an apartment with an energy performance approach. International Journal of Low-Carbon Technologies 2024, 19, 1529-1539. [CrossRef]

- Blázquez, T.; Ferrari, S.; Suárez, R.; Sendra, J.J. Adaptive approach-based assessment of a heritage residential complex in southern Spain for improving comfort and energy efficiency through passive strategies: A study based on a monitored flat. Energy 2019, 181, 504-520. [CrossRef]

- Caro, R.; Sendra, J.J. Evaluation of indoor environment and energy performance of dwellings in heritage buildings. The case of hot summers in historic cities in Mediterranean Europe. Sustainable Cities and Society 2020, 52, 101798. [CrossRef]

- Lozoya-Peral, A.; Perez-Carraminana, C.; Galiano-Garrigós, A.; Gonzalez-Aviles, A.B.; Emmitt, S. Exploring energy retrofitting strategies and their effect on comfort in a vernacular building in a dry Mediterranean climate. Buildings 2023, 13, 1381. [CrossRef]

- Garriga, S.M.; Dabbagh, M.; Krarti, M. Optimal carbon-neutral retrofit of residential communities in Barcelona, Spain. Energy and Buildings 2020, 208, 109651. [CrossRef]

- Ascione, F.; Bianco, N.; Mauro, G.M.; Napolitano, D.F. Retrofit of villas on Mediterranean coastlines: Pareto optimization with a view to energy-efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Applied energy 2019, 254, 113705. [CrossRef]

- Ascione, F.; De Masi, R.F.; de Rossi, F.; Ruggiero, S.; Vanoli, G.P. Optimization of building envelope design for nZEBs in Mediterranean climate: Performance analysis of residential case study. Applied energy 2016, 183, 938-957. [CrossRef]

- Ali, N. A Framework for Designing Energy Efficient Dwellings Satisfying Socio-cultural Needs in Hot Climates. 2018.

- Eltrapolsi, A. The Efficient Strategy of Passive Cooling Design in Desert Housing: A Case Study in Ghadames, Libya. 2016.

- Elaiab, F.M. Thermal comfort investigation of multi-storey residential buildings in Mediterranean climate with reference to Darnah, Libya. 2014.

- El Bakkush, A.F.M. Improving Solar Gain Control Strategies in Residential Buildings Located in a Hot Climate (Tripoli-Libya). 2016.

- Felimban, A.; Knaack, U.; Konstantinou, T. Evaluating savings potentials using energy retrofitting measures for a residential building in Jeddah, KSA. Buildings 2023, 13, 1645. [CrossRef]

- Krarti, M.; Aldubyan, M.; Williams, E. Residential building stock model for evaluating energy retrofit programs in Saudi Arabia. Energy 2020, 195, 116980. [CrossRef]

- Attia, S. Net Zero Energy Buildings (NZEB): Concepts, frameworks and roadmap for project analysis and implementation; Butterworth-Heinemann: 2018.

- Noguchi, M.; Athienitis, A.; Delisle, V.; Ayoub, J.; Berneche, B. Net zero energy homes of the future: A case study of the EcoTerraTM house in Canada. In Proceedings of Renewable Energy Congress, Glasgow, Scotland; pp. 19-25.

- Ruparathna, R.; Hewage, K.; Sadiq, R. Improving the energy efficiency of the existing building stock: A critical review of commercial and institutional buildings. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews 2016, 53, 1032-1045. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).