1. Introduction

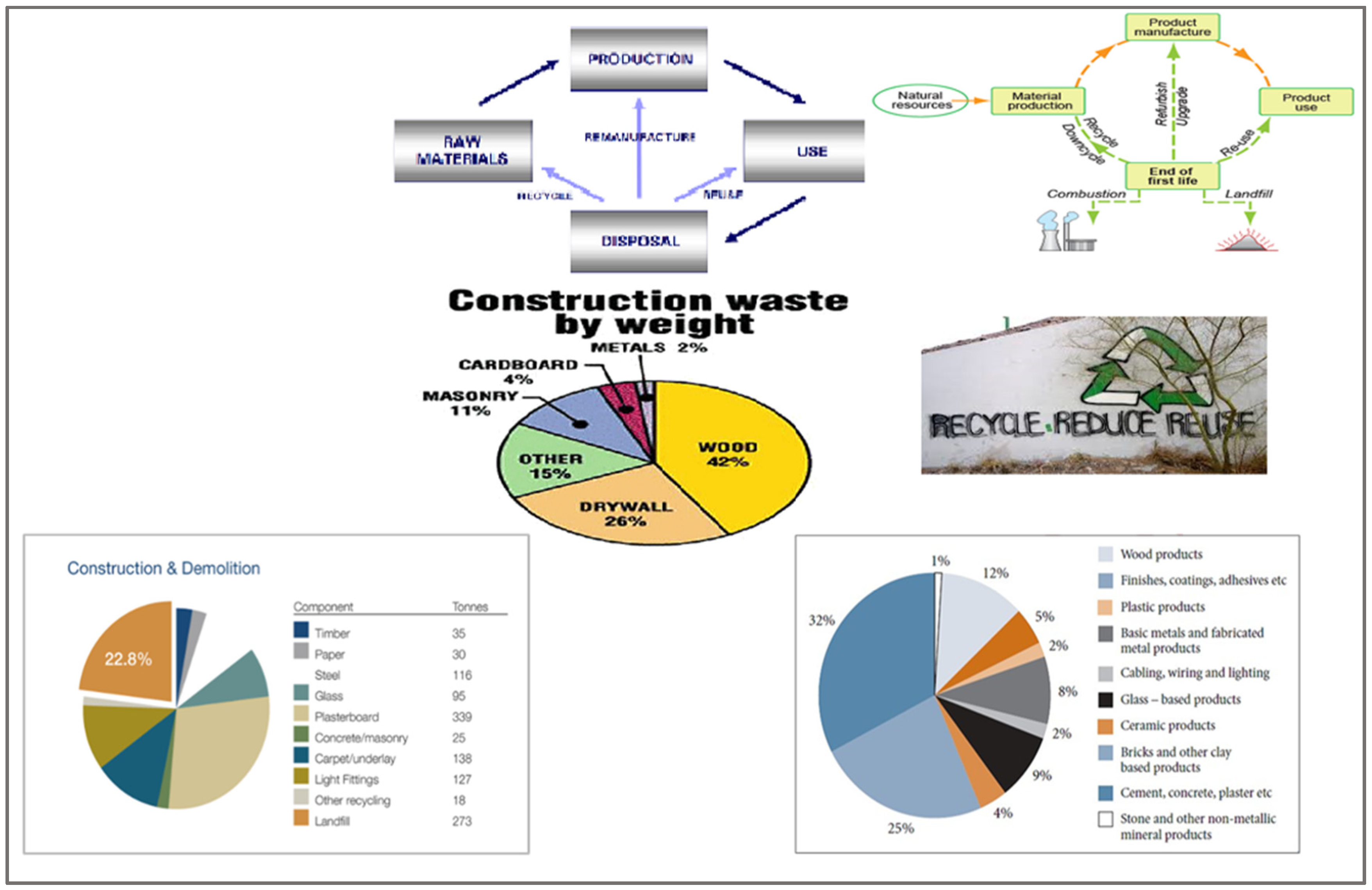

The construction industry continues to be the major stimulant in any country’s economic growth and development, but the industry has long been regarded as one of the major contributors of negative impact on the environment due to the high amount of waste generated from construction, demolition, renovation and associated actions with construction contributing to most of the waste generated annually from the industry [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Generally, waste from construction and demolition actions can be composed of non-biodegradable and inert materials such as concrete, plaster, metal, wood, plastics, or non-inert materials. Waste is typically produced during construction activities like building and demolishing roads, bridges, flyovers, subways, remodeling, or removal of construction [

5,

6,

7]. Bulky materials such as concrete, wood from buildings, asphalt from roads and roofing shingles, gypsum, the key component in drywall, metals, bricks, glass, and plastics, as well as salvaged building materials like doors, windows, and plumbing components, as well as trees, stumps, earth, and rock from clearing sites, are also frequently found as waste [

8,

9,

10]. In most construction projects, approximately 35% of the amount of construction material waste (CMW) generated is sent to landfills without treatment [

11,

12,

13,

14].

The United States contributes approximately 700 million metric tons (Mt) of waste from construction materials annually, followed by the European Union with over 800 million metric tons (Mt) and China with approximately 2.3 billion metric tons (Mt) [

15]. Although, the amount of waste produced at each stage of construction, including demolition and reconstruction, varies according to the type of building and its intended utilization. In 2016, the world’s cities generated 2.01 billion metric tons (Mt) of solid waste, or 0.74 kg per person per day, according to a World Bank Group report on a general assessment of solid waste management [

16,

17]. On a global scale, over 10 billion metric tons (Mt) of CMW are generated annually. The composition of the waste may vary from one place to the other due to the varying economy, natural environment, and construction techniques. However, 70–80% of the waste is typically made up of inert materials like concrete and bricks [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

Figure 1 shows the daily increase in global construction materials waste (CMW) production in kilotonnes/percent excluding quarry waste.

The achievement of sustainable construction is seen to be hampered by the significant and ongoing issue of CMW production. Rapid urbanization in recent decades has led to massive global construction, remodeling, and demolition projects, which have increased the generation of waste from construction and demolition action. Although construction activities are dynamic, the amount and constituent of construction waste are always changing. Because of this, it is challenging to measure various construction waste items precisely. Nonetheless, several initiatives to ascertain the quantity of waste produced during various construction projects and stages have provided information on the amount of waste produced in the construction industry. Wang et al. [

23] establish that material handling, site management, procurement, operations, and design and documentation are the five main critical factors influencing CMW. As a result, efficient waste management can be considered a practice that applies to practically every circumstance in contemporary building projects [

24].

Furthermore, from an economic perspective, sustainable waste management can lower the cost of disposing of waste and potentially boost income from recycled materials. This demonstrates a dedication to sustainability and environmental responsibility, which improves how the public views construction projects and those who are involved [

25,

26,

27]. The goal is to divert waste from landfills in the most practical way possible under normal conditions [

28,

29]. Therefore, there is a crucial need to adopt technological solutions to minimize the negative impacts of waste disposal on the environment and society, as well as to increase the efficiency of material waste management (MWM). Changes in the management of biodegradable (organic) and non-biodegradable (inorganic) are necessary to achieve net-zero waste [

30,

31]. This study utilizes a state-of-art review to deliver an understanding of the possibility of applying a BIM-aided waste management system in minimizing waste generated in any construction project. The aim is to indicate the possibility of applying a dynamic BIM-aided waste management system which can facilitate net-zero waste and indicate the values of adopting it in any construction project. In this study, several pieces of literature were reviewed to give a broad understanding of the value derived in applying BIM-aided tools in construction across its lifecycle. This can be employed to design a suitable and operational framework to aid net-zero waste in any CI.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Advancing Net-Zero Waste in Construction Projects

According to Zero Waste International Alliance (ZWIA), zero waste is a visionary, economical, efficient, and ethical objective that aims to help people change their habits and lifestyles to mimic sustainable ecological cycles. All waste materials are intended to be recycled into resources for future use [

32]. Therefore, designing and managing products and processes to systematically prevent and eliminate the amount and toxicity of waste and materials, as well as to save and recover all resources instead of burning or burying them, is known as “zero waste”. By implementing zero waste approaches, all discharges to the air, water, or land that endanger the health of people, animals, plants, or the world will be eliminated. 90% diversion from landfills and incinerators is the explanation of zero waste [

33,

34,

35]. By putting in place the infrastructure and policies necessary to restructure our production system to utilize fewer resources and design items for recovery rather than disposing of waste, we can drastically move toward zero waste. Furthermore, as we move toward zero waste, we can assist industry in fulfilling their responsibilities by revamping their packaging and products to eliminate non-recyclable, hazardous, and unused substances. A lot of industries and cities have shifted from a zero-waste aim to a “zero waste to landfill” objective, which focuses on lowering the amount of waste that ends up in landfills. The issue with focusing only on minimizing landfill waste is that it indicates burning waste is a better way to produce energy. Waste-to-energy (WTE) is a disposal method that permanently degrades resources; it doesn’t cut waste or save natural resources, and ultimately, burning rubbish to generate energy will use more energy than creating new products from virgin materials. Redesigning our entire cycle of resource extraction, consumption, and disposal management to ensure that no resources are wasted at any stage is the real objective of zero waste instead of simply zero waste to landfill or zero waste to energy [

36,

37,

38].

Waste costs the construction industry an estimated £11 billion per annum and emits 3.5 million tonnes of CO2e. Notwithstanding, waste can be reduced, materials used more efficiently, and buildings and structures at the end of life repurposed, refurbished or dismantled to enable products and materials to be a resource for new activities [

34]. Also, greener construction can be achieved in any construction industry by reaching net-zero waste. According to recent research, the zero-waste concept has become a novel approach to waste management issues, particularly when waste is viewed as a resource. Its application contributes to the best possible use of natural resources and a decrease in environmental problems [

39,

40]. Reducing, reusing, and recovering waste streams and converting them into useful resources while sending zero waste to landfills annually is the goal of achieving net zero waste cities. Building procurement teams, empowered work teams, lean designing, education and training, awareness of waste-management systems, senior management commitment, technological innovation, organizational culture changes, and individual behavior changes are some of the factors we propose as catalysts for reaching net-zero waste [

41,

42,

43,

44].

According to UK Statistics, Costs can be reduced by 10% by 2030 by optimizing materials and planning out waste. Get all but hazardous construction and demolition waste out of landfills by 2040. Reduce the amount of soil sent to landfills by 75% by 2040 in comparison to 2020 levels, and by 2050, it should be zero unless it is necessary for landfill operations [

45,

46,

47]. However, zero waste is a comprehensive approach that focuses on waste elimination at the source and throughout the supply chain. According to Ahankoob et al. [

48], in managing CMW, Building Information Modelling (BIM) technologies can be used in conjunction with platforms like Revit, Micro Station, Archi CAD, and Tekla. Although, CMW can be handled primarily by employing preventative and minimization techniques [

49]. To be regarded as “best practice,” CMW managerial procedures should strive to divert as many materials from landfills as possible. Therefore, waste managers should aim to maintain clean material loops to maximize current CMW recycling operations and reduce adverse future effects. Furthermore, waste management is promoted by training and supervision, labor and subcontractor management, material handling and control, procurement, communication, and documentation [

50,

51].

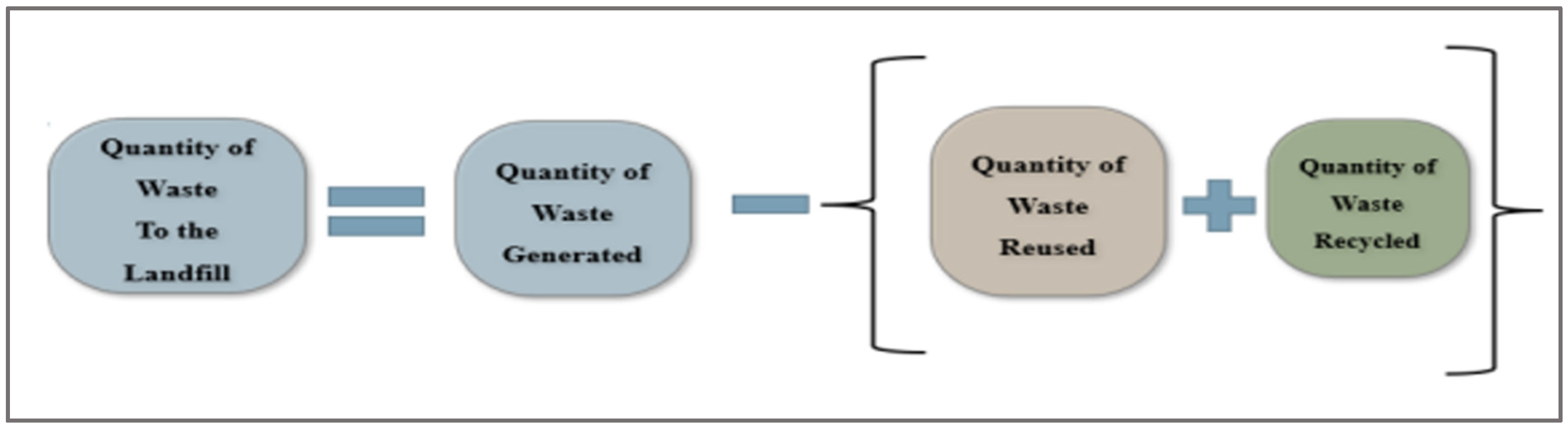

Ling and Nguyen [

52] indicate that the environmental management system (EMS) and life cycle assessment are key tactics for putting the zero-waste idea into practice. It has been established that BIM technology offers a wide range of influences in eliminating/reducing waste in construction action on sites. Consequently, zero waste is a holistic view of the sustainable avoidance and management of waste and resources in construction projects [

53]. As illustrated in

Figure 2, to satisfy the requirement for the net amount of waste sent to the landfill to be “zero,” a building or built environment must indicate that the total amount of waste produced during construction and operation is equal to the amount of waste recycled and reused on the site. Through a multifaceted strategy that includes nature-centric design, minimizing debris during building, handling waste responsibly throughout the operation, reusing as much of the waste as possible, and recycling the remaining material, this will eliminate the diversion of waste being sent to landfills. Therefore, the construction sector must develop a dynamic BIM-aided waste management system that can impact on the net-zero waste cities transitioning into both the construction and demolition waste sectors [

54,

55,

56].

To advance zero waste strategies from specialized applications into the mainstream and ultimately shift economies away from the take-make-trash model and toward a circular economy, cooperation between various kinds of stakeholders including citizens, the private sector, and the governments is highly required. Also, technological developments have a particularly significant role in shaping waste management practices to meet zero waste targets. As the world’s waste output increases, integrating cutting-edge technology becomes more crucial to maximizing resource recovery, reducing environmental impact, and promoting sustainable waste management practices [

57,

58].

2.2. Pathway to Net-Zero Cities Transitioning

A net-zero emissions future where everyone has access to affordable, clean energy depends on government effort. By 2050, 70% of people worldwide are predicted to live in cities, up from 50% in 2021 [

59]. Currently, cities are responsible for 75% of the world’s energy consumption and 70% of its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. However, opportunity comes with size. A frequently discussed subject in the history of several regions, particularly in the last several decades, is the idea of retrofitting and redesigning cities to make them more economically competitive, socially justifiable, and ecologically benign [

60,

61,

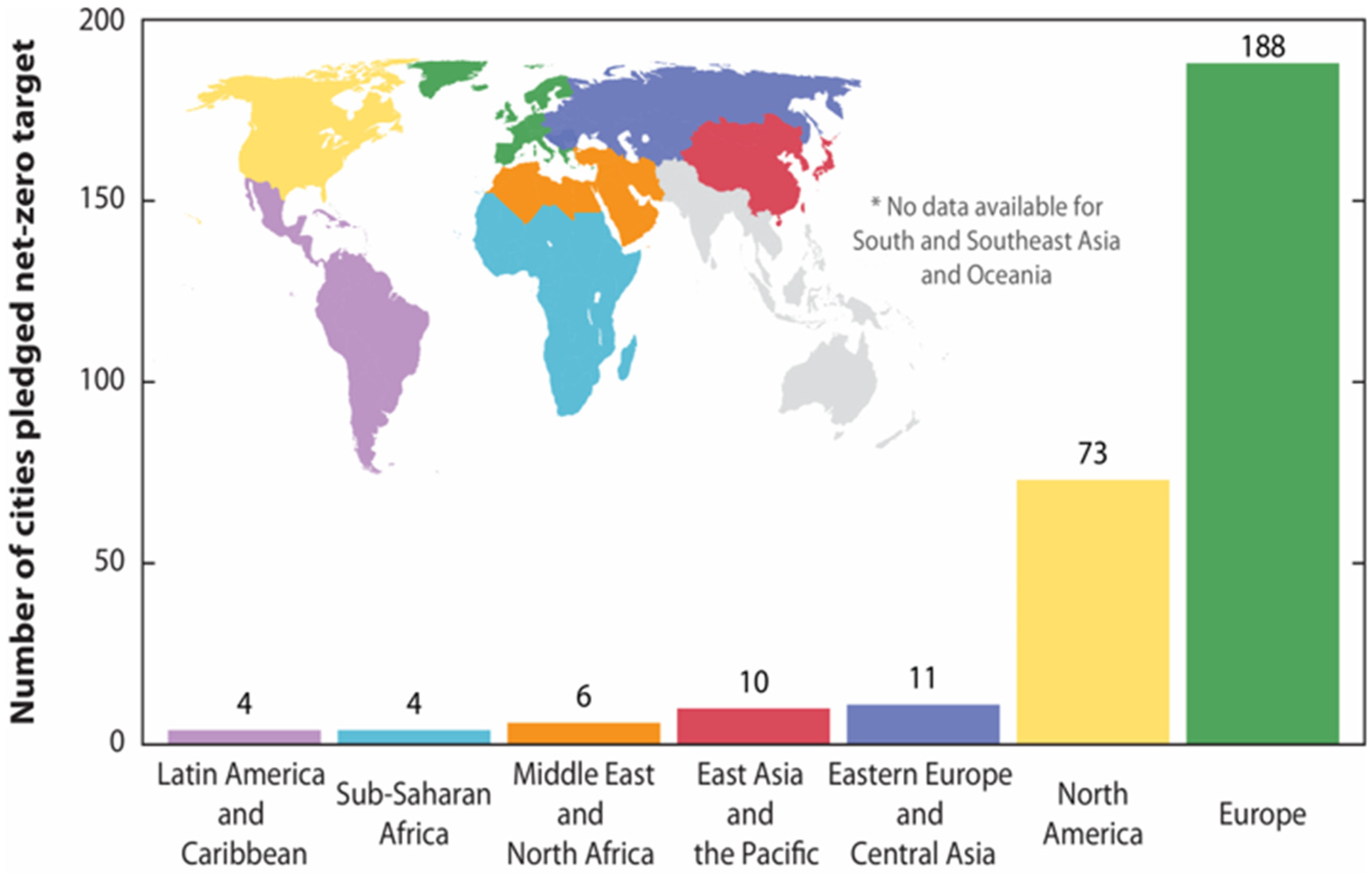

62]. Even while zero-carbon cities are a relatively recent development, ancient civilizations across the world have evolved around the concept of reduction in GHG emissions. While the goal of the net-zero waste techniques is to gradually eliminate waste by developing and putting in place systems that don’t produce waste in the first place, rather than by burning or disposing of it in landfills, a rising number of regions have set net-zero as their goal after realizing their potential to help combat climate change with over 800 cities worldwide having committed to being zero- emissions cities as of December 2024 [

63,

64].

The fundamental idea behind these cities, which are also known as climate-neutral cities, net-zero energy cities, carbon-free cities, or carbon-neutral cities, is the same: drastically cutting greenhouse gas emissions from urban activities while also eliminating greenhouse gas emissions from the atmosphere [

65]. Therefore, the fact that more and more communities are pledging to achieve net-zero goals is a positive development, but it is uncertain if they have the means or political will to follow through on their promises. Transnational networks are actively developing guidelines, strategies, and protocols to build a common set of definitions and techniques to achieve net-zero emissions [

66]. There are many working definitions of a net-zero city and approaches to the goal of net-carbon emission. Of fact, what is being reduced to zero and by what timeframe much depends on how carbon emissions are assessed, and which industries are counted. In this study, we define net-zero cities as those that have signed up for an initiative that aims to achieve such a decarbonization goal or have committed to an emissions reduction target with a goal of at least 80% reduction in GHG emissions [

67,

68,

69].

The shift to a sustainable society will depend on our cities achieving net zero. Enabling individuals with the tools to manage their own energy identities may be crucial to the shift. The goal of the net-zero waste method is to gradually eliminate waste through the development and implementation of systems that prevent waste from being generated in the first place, as an alternative to burning or disposing of it. The reusable waste-regenerated resources might take the place of raw materials and fossil fuels, minimizing greenhouse gas emissions even further and easing the transition to net zero in cities. By fostering social mobilization and implementing waste-treatment procedures that might reduce greenhouse gas emissions across the waste disposal and treatment life cycle, policymakers can establish a sustainable solid waste management framework [

70,

71,

72]. As illustrated in Figure-3, major cities of the world have pledged to net-zero targets, part of which is their commitment to utilize strategies that can assist in the implementation of zero-waste in the construction industry are elaborated with external influences and constraints.

2.3. BIM-Technology Application in Minimizing Waste

In any country’s drive toward sustainable development, there is a need to provide a sustainable way to minimize or eliminate the waste generated on construction, and the application of Building Information Modelling (BIM) technology has been seen as one of the best tools [

73]. A BIM is an advanced way of managing social and technological resources that makes sense of the concepts of complexity, cooperation, and interrelationship, which are the most vital players in today’s building environment [

74,

75]. The goal of this management system is to find the correct information at the right time and in the right location. Furthermore, BIM is a parametric component-based, three-dimensional reference structure modeling system developed using file formats that enable data sharing amongst all disciplines engaged in the project life cycle [

76,

77,

78]. However, BIM is more than just software, technology, and/or tools; it is the entire collection of procedures that generate and manage all data defining a building’s life cycle. The ’master builder’ term, which signifies that architect accepted complete responsibility for the project in ancient times, evolved into a ‘master of digital architecture’ for BIM in today’s design and construction world [

79]. According to Liu et al. [

80] and Li et al. [

81], many experts in the construction industry, such as architects, engineers, and surveyors, go a step further and believe the application of BIM technology to be a crucial role in the struggle against construction and/or demolition waste. The discourse attempts to demonstrate the potential advantages of BIM, such as clash detection and on-site collaboration.

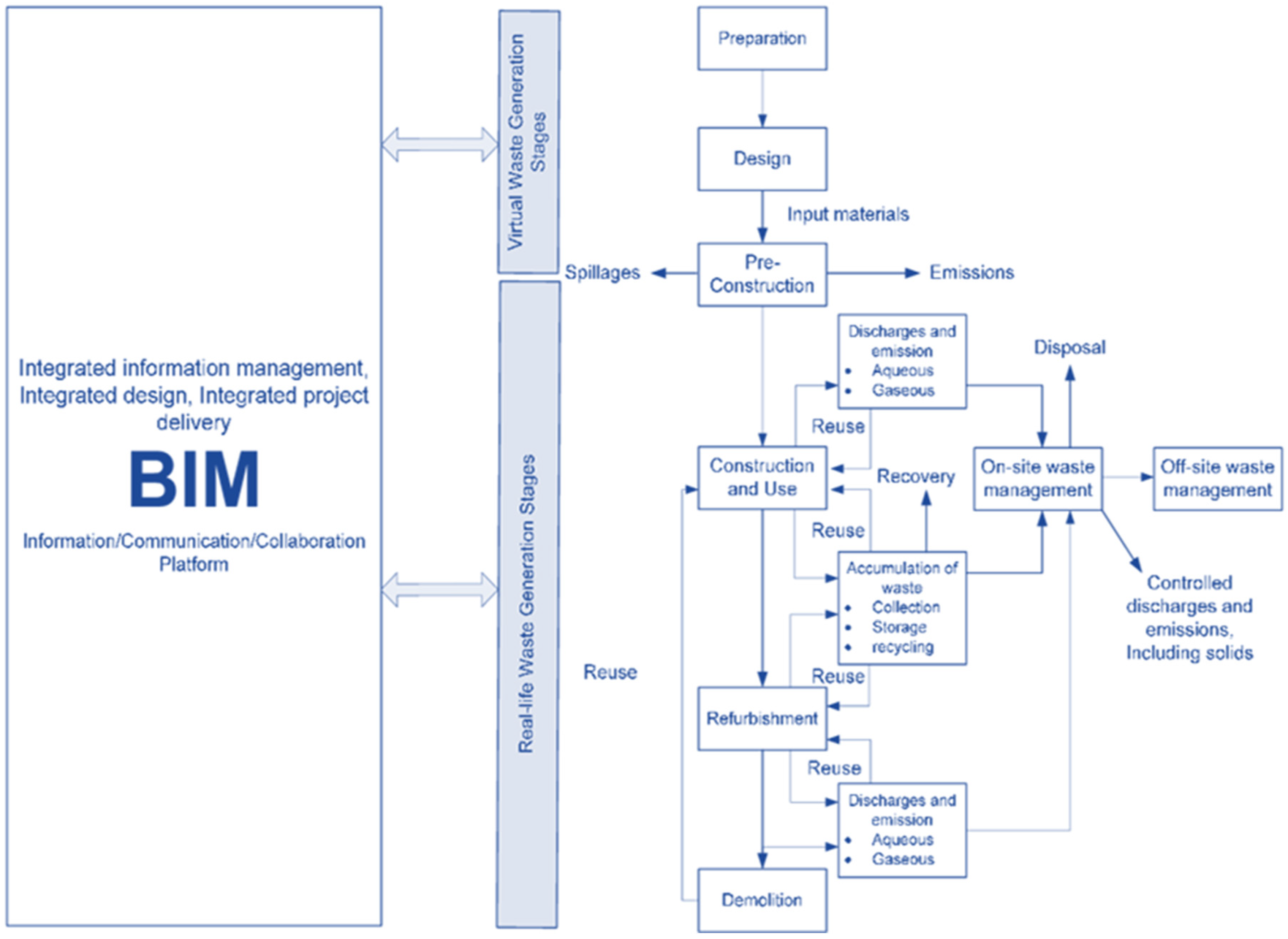

However, due to these potential benefits, BIM has been promoted as a solution to waste generated during construction and demolition activities. This is due to the BIM’s supply of both virtual and computational environments for considering various design alternatives and building methods, hence reducing waste before it is generated on-site [

82,

83]. Won et al. [

84] proposed BIM as an effective way to reduce construction waste by enhancing the quality and accuracy of design and construction, as well as decreasing design errors, rework, and unexpected modifications. It is a potential solution for avoiding the principal sources of construction and/or demolition waste that occur throughout both the planning and construction phases. According to Baldwin et al. [

85], BIM can be utilized in the design information modeling to evaluate the options to reduce construction waste in high-rise residential buildings which include prefabrication and pre-cast. It was concluded that BIM represents a good platform for developing the analysis of construction waste and the implications of design decisions. Cheng et al. [

86,

87] state that people have tried and succeeded in using BIM to reduce improper design, residues of raw materials, unexpected changes in building design and improve procurement, site planning, and material handling in construction management. Wang et al. [

88] state that a relatively new methodology that people in the construction industry are using to minimize the generation of waste in the design and pre-construction phase is the use of BIM technology.

Svalestuen et al. [

89] and Rajendran and Gomez [

90] suggest that BIM technology might be used to reduce construction waste, however their efforts were restricted to the design phase and did not address the specific strategies for using BIM to reduce waste. However, the study did not offer specific ways for reducing and managing building waste. Furthermore, the UK Construction 2025 Strategy recognized BIM’s potential to minimize construction waste during the design and construction phases [

91,

92]. Unfortunately, no efforts have been undertaken to build BIM-assisted construction waste management design decision-making tools and techniques to date. Furthermore, there is insufficient study on the creation and review of tools and methodologies that leverage BIM to aid in waste management decision-making throughout the design phase of projects. Furthermore, no studies have attempted to link the use of BIM to building waste sources [

93,

94,

95].

BIM’s ability to forecast outcomes is the foundation of its use in waste management. By precisely forecasting the number of materials needed for a project, BIM helps reduce excess orders and the waste that follows. Furthermore, it offers information on waste production at various stages of construction, which makes proactive waste management and recycling planning possible [

96,

97]. Nevertheless, BIM’s impact goes beyond material waste. It provides a chance for ’deconstruction’ rather than ’demolition.’ BIM can organize and oversee systematic deconstruction when a structure reaches the end of its useful life, allowing for material recovery, recycling, and reuse. In addition to decreasing waste, this strategy lowers the need for new materials, saving valuable resources [

98]. With BIM, the idea of smart design is also strengthened. Architects and engineers can improve the design for resource conservation and energy efficiency, reducing long-term waste, by modeling a variety of situations and settings. BIM provides significant cost savings and, more significantly, long-term environmental advantages despite its initial investment. When paired with effective project management, the value proposition of BIM is difficult to overlook. The elimination of material waste alone can result in significant cost savings [

99,

100,

101].

Figure 4.

BIM platform and conceptual construction waste material input-output [

44].

Figure 4.

BIM platform and conceptual construction waste material input-output [

44].

BIM applications such as design validation, quantity take-off, phase planning, and site usage planning, among others, have been proposed to reduce construction waste. BIM can also help us reduce waste by improving the quality and accuracy of design and construction, decreasing design errors, rework, and unplanned changes. Furthermore, the use of BIM can reduce improper design, residues of raw materials, and unexpected changes in building design while improving procurement, site planning, and material handling in construction management [

101]. Burcu et al. [

102] and Eze et al. [

74], list all the basic BIM solutions for waste reduction including conflict, interference and collision detection, construction sequencing and construction planning, reducing rework, synchronizing design and site layout, detection of errors and omissions (clash detection) and precise quantity take-off. During the design phase, BIM can be utilized to establish an efficient schedule for the procurement, production, and delivery of all building materials, hence minimizing waste. Precise program scheduling lowers the risk of damage and enables just-in-time delivery of equipment and commodities [

103,

104,

105,

106,

107]. When utilized for automated equipment and component production, BIM enables more efficient materials handling recovery. Among the essential aspects that make waste minimization possible are site investigation, cost estimation, and modeling of existing circumstances, all of which are facilitated by BIM [

108,

109,

110,

111,

112,

113,

114,

115,

116,

117].

Table 1.

Selection of BIM-aided tool and its application at each construction lifecycle phase [Author].

Table 1.

Selection of BIM-aided tool and its application at each construction lifecycle phase [Author].

| Lifecycle phase |

BIM-aided Tools |

Citations |

|

| Planning |

Existing condition modeling |

Ahankoob et al., 2012; Akbarnezhad et al., 2014 |

|

| Waste estimation |

Eastman et al., 2011; Cheng et al., 2013; Eze et al., 2024 |

|

| Phase planning |

Bloomberg et al., 2012; Akinade et al., 2016. |

|

| Site analysis |

Soharu et al., 2022; Goldsmith et al., 2017; Eze et al., 2024. |

|

| Design |

Validation of designs |

Olatunji et al., 2010; Akinade et al., 2016; Akinade et al., 2018. |

|

| Quantity Take-Offs (QTO) |

Cheng et al., 2013; Akinade et al., 2018; Eze et al., 2024. |

|

| Synchronizing design and site layout |

Crotty, 2012; Akinade et al., 2018; Aboginije et al., 2020; Soharu et al., 2022. |

|

| Rework reduction |

Dave, 2013; Ling & Nguyen, 2013; Goldsmith et al., 2017. |

|

| Procurement/Construction |

Project sequencing |

Griffith, 2004; Fapohunda, 2009; Olatunji et al., 2010; Aboginije et al., 2020. |

|

| Asset tagging |

Akinade et al., 2018; Saima et al., 2020; Soharu et al., 2022. |

|

| 3D geometry |

Akinade et al., 2016; Mollasalehi et al., 2016; Svalestuen et al., 2017. |

|

| Integrating energy analysis |

Eastman et al., 2008; Cao et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2017. |

|

| 3D coordination |

Svalestuen, et al., 2017; Akinade et al., 2018; Aboginije et al., 2020; Soharu et al., 2022. |

|

| Site utilization planning |

Eastman, 2011; Won et al., 2016; Lu et al., 2017. |

|

| 3D control and planning |

Arayici et al., 2011; Akinade et al., 2018. |

|

| Operation |

|

|

| Maintenance scheduling |

Akinade et al., 2018; Saima et al., 2020; Soharu et al., 2022. |

|

| Tracking/space management |

Cheng et al., 2013; Akinade et al., 2018; Eze et al., 2024. |

|

| Disaster planning |

Soharu et al., 2022; Goldsmith et al., 2017; Eze et al., 2024. |

|

| Record modeling |

Bloomberg et al., 2012; Akinade et al., 2016. |

|

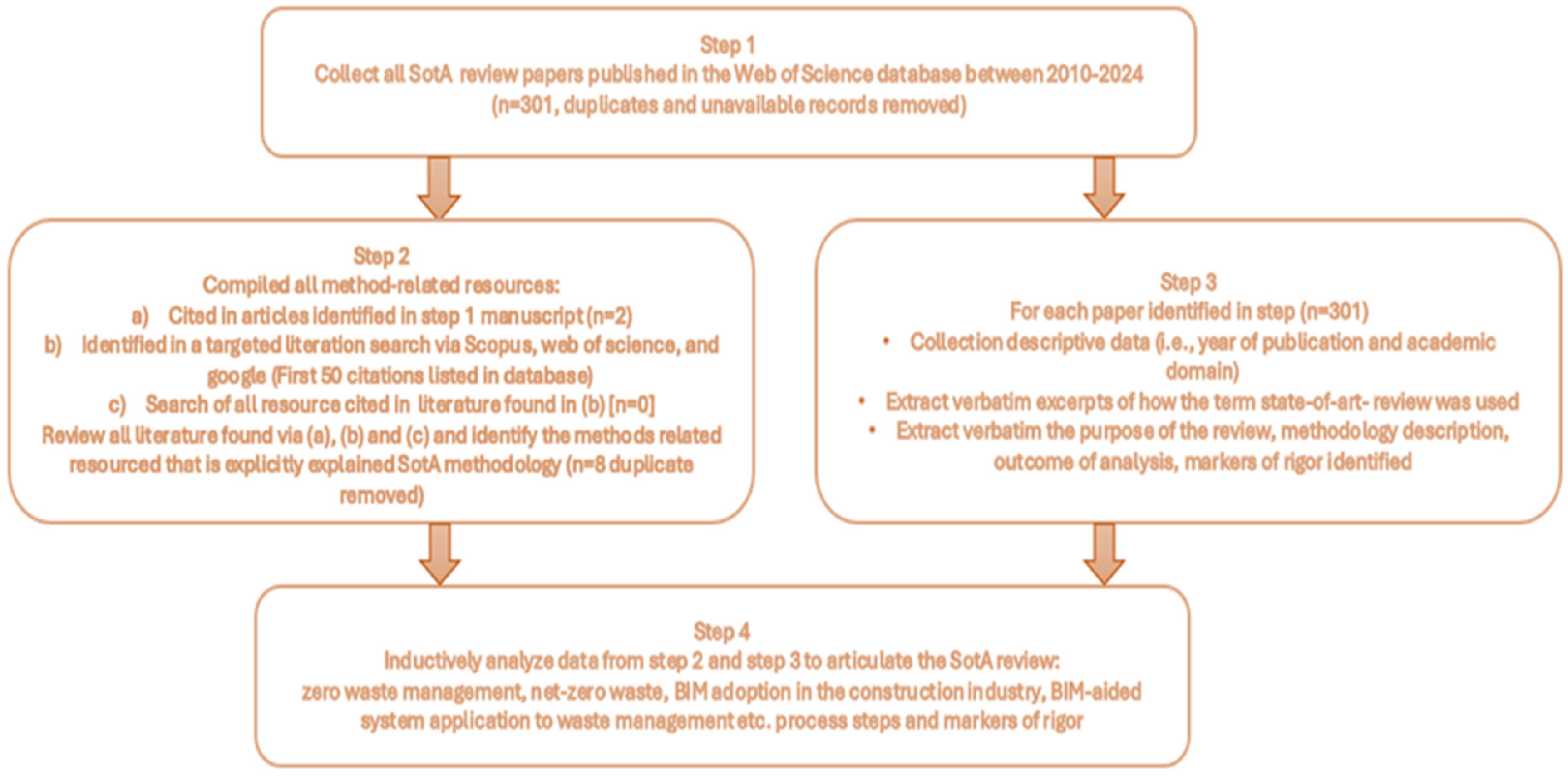

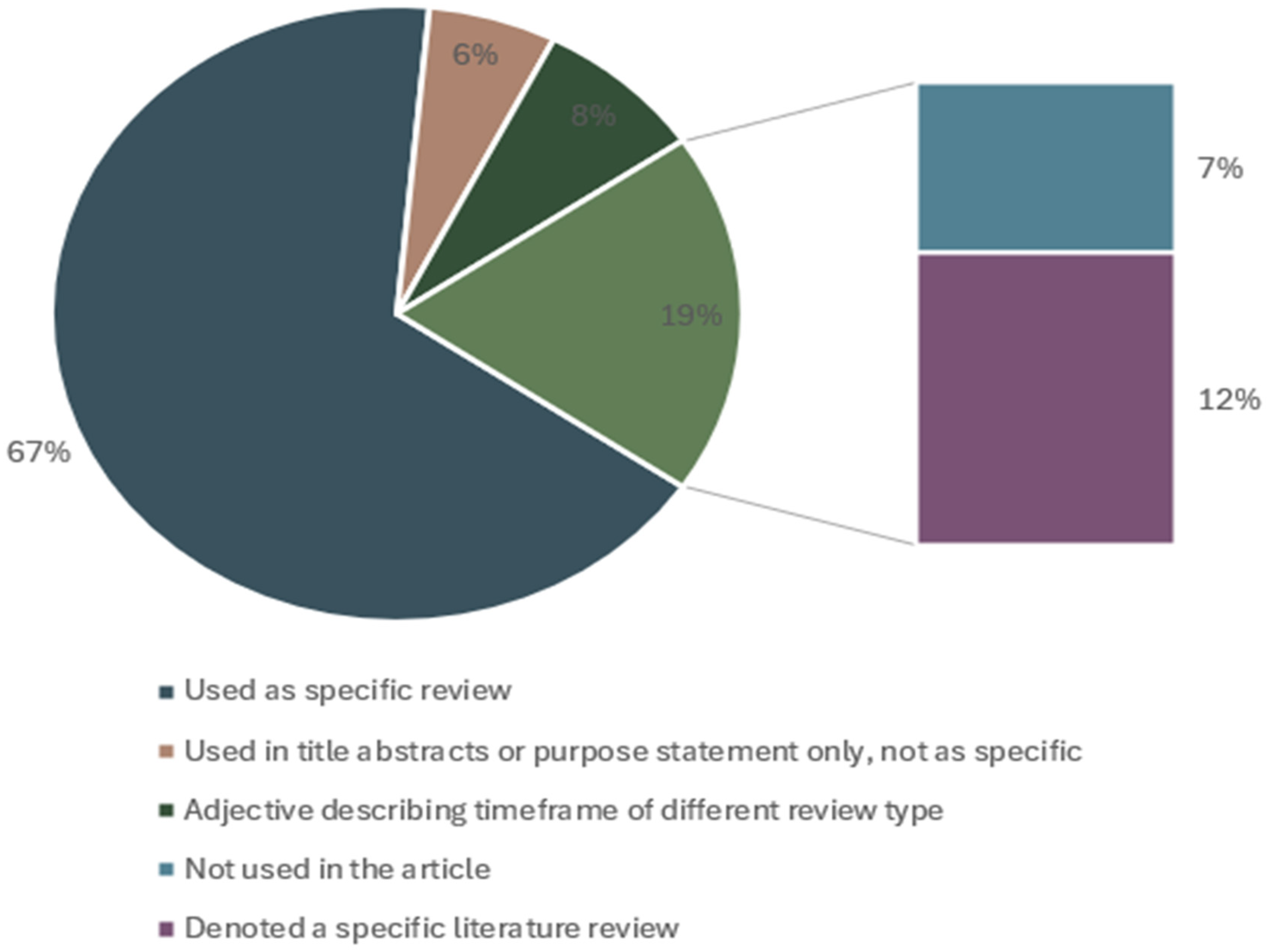

3. Methodology and Design

Despite several kinds of literature review methods incorporate multiple bodies of work, state-of-art (SotA) analyses provide something distinct. SotA appraisals explore questions like: Why did our knowledge grow in this way? by examining the historical development of a body of information. What additional possibilities might our research have explored? Which paradigm shifts in our thinking need to be revisited to acquire fresh perspectives? A SotA review, which is a type of narrative knowledge synthesis, recognizes that history is a collection of choices and then speculates about the possible alternatives [

118,

119,

120]. To achieve the aim of determining the potential solutions for implementing a BIM-aided waste management system, this study employs a cutting-edge SotA review technique. The SotA review approach is developed using a four-step research design procedure as illustrated in

Figure 5. The first and second steps indicated how data were collected and extracted, while the third and fourth steps indicated data processing and analyses.

3.1. Data Collection and Extraction

Selection was made based on a list of keyword combinations from the most cited research papers on BIM implementation in CMW that were published in esteemed academic publications about the CMW, BIM, and sustainability domains, the authors were able to focus on the scope of the literature search. The literature’s overall scope is restricted to English-language journal and conference articles published between 2010 and 2024. The Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus were chosen as the primary search engine for this study because of the strength and breadth of its databases, which indicate their most prestigious academic journals. The WoS Core Collection-Citation Index, which comprises the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED), and the Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Science (CPCI-S), is the source of the literature data.

Out of the total searches, 301 peer-reviewed publications were found in the Web of Science database. The search results were then exported to Microsoft Excel. 84 duplicate items were removed from the preliminary search by using filters to eliminate them. The impact factor (IF) and citation score, which indicate the degree of influence and rate of citations of the research published in the journals, were then used to further narrow down the selection of peer-reviewed academic publications. Only 117 peer-reviewed academic papers that represented the foundation and cutting-edge knowledge on CMW production, BIM, and the various applications in CMW waste management domains closely matched this research topic, according to an analysis of the titles and abstracts.

3.2. Data Processing and Analysis

All articles that met the requirement were obtained and analyzed. An inductive analytical method was used to first familiarize the researcher with all the concepts used in the research. Noting similarities between articles, observing thought patterns that have influenced current understandings of the subject, commenting on the presumptions underlying shifts in understandings, identifying key turning points in the evolution of understanding, and identifying gaps and assumptions in current knowledge constitute every part of this familiarization. Then, the current body of knowledge and the future direction of the research were identified. BIM applications across lifecycle stages of construction projects, and how it can be a tool in eliminating waste in construction activities was critically examined and interpreted in this study.

4. Discussion

In construction projects, the value of BIM technology must be maximized, therefore all aspects of the construction life-cycle phase where the technology can be employed must be determined to meet the expectations of the designers and contractors. In addition, a more valuable aspect of BIM technology is the ability of the technology to be a model to drive lean construction and avoid waste during the project. At each stage of the construction project, designers are expected to maximize the value of BIM applications to minimize waste. The procedures for using a BIM-aided waste management system to achieve net-zero waste are based on a construction waste management framework designed through a life-cycle mapping. Despite its relatively short existence, BIM has become invaluable to builders, particularly during the planning phase. In this phase, BIM provides the framework at the earliest stage of the project. A digital representation of all physical and functional elements is generated, reviewed, shared, and revised long before anything gets built. So, if the architectural design conflicts with the structural engineering plans, the builder can address and change course early on. If there’s a discrepancy with the construction component, the issue can be resolved before ordering any materials and starting on the labor. Creating a virtual model in the planning phase, before construction begins makes it possible to prevent unnecessary errors, improve productivity, and make well-informed decisions.

To eliminate waste during the construction planning phase, BIM can be utilized to produce an efficient schedule for material ordering, fabrication, and delivery of all building components. Precise program scheduling allows for just-in-time supply of materials and equipment, which reduces the risk of damage. The use of BIM for automated manufacture of equipment and components allows for more effective material handling recovery. Site analysis, cost calculation, and modeling of current circumstances are some of the key features of BIM that enable waste minimization. In the design phase, problems are solved early in the design. Hence there will be fewer controversial problems in the plans. Any design changes entered into the building model are automatically updated. Hence, there will be less rework due to possible drawing errors or omissions. The development of the concept design into a dimensionally correct and coordinated design, describing all the main components of the building and how they fit together is required. This will provide sufficient information for applications for statutory approvals to begin. However, specific technical aspects of the design such as LEED evaluation, code validation, and necessary analysis must be addressed before it is developed fully in the next stage. Also, by linking the 3D objects in the design model to the construction plan a clear procedure of activities is developed and hence it is possible to show how the building and the site would look at any point in time.

BIM-aided tools can reduce the number of additional handlings, wasteful transportation, and material loss. The procurement stage primarily includes project sequencing, take-offs, integrating energy analysis with 3D geometry, asset tracking, and so on. Working in a collaborative atmosphere increases overall productivity by reducing time and resource waste when compared to working independently. When we create a model, we can also enter a large amount of building data into it, which can then be used to extract quantities, budgets, and costs during the construction process. While BIM can be highly valuable across the entire construction phase. For instance, virtual construction Modelling is extremely cost-effective when utilized during the construction phase. With complex designs and detailing, it is better to use BIM during the construction stage with scheduling, 4D and 5D, Installation Drawings, etc. However, the application of BIM at the operation stage includes maintenance scheduling, building system analysis, asset management, tracking and/ or space management, and disaster planning.

Furthermore, by presenting an in-depth analysis of the materials used in construction, 6D BIM makes it easier to establish waste reduction initiatives. This involves keeping tabs on the materials’ provenance, makeup, and disposal techniques. Construction projects can greatly lessen their environmental impact and support sustainable waste management by encouraging recycling and optimizing material utilization. The reduction of material, equipment, and resource waste is possible by using 6D to optimize planning and control. Improving the choice of environmentally friendly resources through astute procurement and business partner management procedures. Optimizing the supply chain to cut down on carbon emissions from moving equipment and commodities. With complex workflow management and all data readily available on the platform for everyone to access, fewer documents are used. Computation and qualification of the environmental impact of a product from start to finish and integration of structured and unstructured data sources from a dispersed and non-standardized environment using an open “building passport” platform.

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

Through SotA review, this study examines the waste origins and causes of waste generation, then emphasizes the essential of sustainable waste management practices, and as well as an examination of existing BIM applications that are currently used in waste management was reviewed. The potential to improve CMW through the application of BIM-aided systems in construction has been investigated. Therefore, the application of BIM-aided waste management to minimize CMW is here to stay for a long time and will further advance in years to come. The most important conclusion drawn from this article is that, despite the necessity of investigating the application of BIM for CMW management, no prior efforts have been made to use BIM as a tool to cut down on construction waste. Effective collaboration between lean construction and BIM-based approaches is crucial for CMW management since they both emphasize process modifications involving many project participants. However, the benefits of managing and minimizing waste with the proposed BIM-aided techniques are not discussed in this review. Therefore, to assess the true efficiency of BIM in reducing and managing CMW, these strategies will be tried in experimental BIM projects in the future.

As a result, the CI can achieve sustainability with the implementation of a BIM-aided waste management system by identifying the need based on the unique characteristics of its building phases. However, integrating the system and data throughout each phase is tremendously advantageous. The same structure that was developed during the conceptual design phase can be improved at each stage and used for construction waste management. Throughout each phase, different personnel can take ownership of the BIM-aided waste management system. Finally, exploiting the advantages invested in the process and design of the model should be need-based and connected with the overall requirement of the CI’s sustainability, as utilizing when there is no need is not productive overall. Also, further research can concentrate on optimizing the application of BIM-aided waste management systems to cope with the emerging complexity of waste minimization in several countries.

Abbrev iations

| BIM |

Building Information Modeling |

| CI |

Construction Industry |

| CO2 |

Carbon dioxide |

| CMW |

Construction Material Waste |

| EMS |

Environmental Management System |

| GHG |

Greenhouse gas |

| QTO |

Quantity Take-Offs |

| SotA |

State-of-the-art |

| WTE |

Waste to Energy |

Author Contributions

All the authors contributed extensively to the work presented in this research. “Conceptualization, A.J. and C.O; methodology, A.J.; validation, A.J., C.O. and B.D.; formal analysis, A.J.; investigation, A.J.; resources, A.J.; data curation, A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J.; writing—review and editing, A.J.; visualization, A.J; supervision, C.O. and B.D., project administration, A.J.; funding acquisition, C.O.

Funding

This research was under the administration of the National Research Foundation (NRF) South Africa, grant number UID: 13042. The APC was funded by cidb Centre of Excellence & Sustainable Human Settlement and Construction Research Centre, Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg 2092, South Africa.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

This work is based on research wholly supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant number UID: 130423).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Marzouk, M and Azab, S. Environmental and economic impact assessment of construction and demolition waste disposal using system dynamics. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 2014, (82), pp. 41-49. [CrossRef]

- Elgizawy, S.M. , El-Haggar, S.M. & Nassar, K. Approaching Sustainability of Construction and Demolition Waste Using Zero Waste Concept. Low Carbon Economy. 2016, 7(1), pp. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Krausmann F, Wiedenhofer D, Lauk C, et al. Global socioeconomic material stocks rise 23-fold over the 20th century and require half of annual resource use. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2017, 114: 1880–1885. [CrossRef]

- Aboginije, A.J. , Aigbavboa, C. O., Thwala, W., Samuel, S. Determining the impact of construction and demolition waste re-duction practices on green building projects in Gauteng province, South Africa. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Industrial Engineering and Operation Management, Dubai, UAE, 2020, 10-12 March; pp. 1027–1038.

- Aboginije, A.J. , Aigbavboa, C.O., Thwala, W. A holistic assessment of construction and demolition waste management in the Nigerian construction projects. Sustainability. 2021, 13 (11): pp. 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wu, H.; Zhang, H.; Duan, H.; Wang, J.; Jiang, W.; Dong, B.; Liu, G.; Zuo, J.; Song, Q. Characterizing the generation and flows of construction and demolition waste in China. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 136, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagapan, I.S. , Abul-Rahman., Asmi A. Factors contributing to physical and non-physical waste. Journal of Advances in Applied Sciences. 2012, vol: 1, pp. 1-10.

- Wilson, D.C. , Velis, C.A., Rodic, L. Integrated sustainable waste management in developing countries. In: Proceedings of the Ice—Waste and Resource Management. 2013, 166, pp.52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, S.O. , Oyedele, L.O., Akinade, O.O., Bilal, M., Alaka, H.A. and Owolabi, H.A. Optimising Material Procurement for Construction Waste Minimization: an exploration of success factors. Sustainable Materials and Technologies. 2017, 11, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, L.L.; Ofori, G. Construction material waste source evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2nd Southern Africa conference on sustainable Development in the Built Environment, Pretoria, 2000, 23-25 August; pp. 1–6.

- Fapohunda, J.A. Operational framework for optimal utilisation of construction resources during the production process. PhD thesis, Sheffield Hallam University, UK, 2009, pp. 112-114.

- Bojan, R. , Neven, V., Branka, I. Concept of sustainable waste management in the city of Zagreb: Towards the implementation of circular economy approach. Journal of the Air and Waste Management Association. 2017, pp. 241-259.

- Menegaki, M. , Damigos, D. A review on current situation and challenges of construction and demolition waste management. Current Opinion on Green Sustainable Chemistry. 2018, 13, pp. 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhawamdeh, M. , and Angela, L. Construction Waste Minimization: A Narrative Review. The International Journal of Environmental Sustainability, 2021, 18 (1): 1-33. [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Global Waste Management Outlook 2024. Available in: https://www.unep.org/resources/global-waste-management-outlook-2024, pp. 33-40.

- Purnell, P. On a voyage of recovery: a review of the UK’s resource recovery from waste infrastructure. Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure. 2019, 4 (1) pp. 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Sandanayake, M.; Muthukumaran, S.; Navaratna, D. Review on Sustainable Construction and Demolition Waste Management—Challenges and Research Prospects. Sustainability. 2024, 16(3289), 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.Y.; Yuan, H.P.; Chen, Q. Science mapping approach to assisting the review of construction and demolition waste management research published between 2009 and 2018. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragossnig, A.M. Construction and demolition waste—Major challenges ahead! Waste Management & Research. 2020, 38(4):345-346. [CrossRef]

- Cudecka-Purina, N.; Kuzmina, J.; Butkevics, J.; Olena, A.; Ivanov, O.; Atstaja, D. A. Comprehensive Review on Construction and Demolition Waste Management Practices and Assessment of This Waste Flow for Future Valorization via Energy Recovery and Industrial Symbiosis. Energies. 2024, 17(5506), 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D. C. , Rodic, L., Scheinberg, A., Velis, C. A., & Alabaster, G. Comparative analysis of solid waste management in 20 cities. Waste management & research. 2012, 30(3), pp. 237-254. [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, S. , Martinez-Vazquez, P., Baniotopoulos, C. Waste Generation Factors and Waste Minimisation in Construction. In: Ungureanu, V., Bragança, L., Baniotopoulos, C., Abdalla, K.M. (eds) 4th International Conference “Coordinating Engineering for Sustainability and Resilience” & Midterm Conference of CircularB “Implementation of Circular Economy in the Built Environment”. CESARE 2024. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering. 2024, vol 489. Springer, Cham, pp. 1-3. [CrossRef]

- Aboginije, A. , Aigbavboa, C., Thwala, W. Modeling and usage of a sustainametric technique for measuring the life-cycle performance of a waste management system: A case study of South Africa. Front. Sustain. 2023, 3:943635. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zuo, J.; Yuan, H.P.; Zillante, G.; Wang, J.Y. A review of performance assessment methods for construction and demolition waste management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 150, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. , Wu, H., Duan, H., Zillante, G., Zuo, J., Yuan, H. Combining Life Cycle Assessment and Building Information Modelling to account for carbon emission of building demolition waste: A case study. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2019, 172, pp. 3154–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISWA, UN. (2015). Global waste management outlook. United Nations Environment Programme. International Solid Waste Association. Available in: https://www.unep.org/ietc/resources/publication/global-waste-management-outlook-2015.

- Papargyropoulou, E. , Preece, C., Padfield, R., Abdullah, A.A. Sustainable construction waste management in Malaysia: A contractor’s perspective. Proc. of the Int. Conf. on Manag. Innov. a Sustain. Built Environ. (MISBE2011) (Amsterdam) (Holland: Delft University of Technology). 2011, pp 1-10.

- Mashudi, Sulistiowati, R., Handoyo, S., Mulyandari, E., Hamzah, N. Innovative Strategies and Technologies in Waste Management in the Modern Era Integration of Sustainable Principles, Resource Efficiency, and Environmental Impact. International Journal of Science and Society. 2023, 5(4), pp. 87-100.

- Jagun, Z.T. , Daud, D., Ajayi, O.M. et al. Waste management practices in developing countries: a socio-economic perspective. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2023, 30, 116644–116655, pp. 2-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasidharani, B. and Jayanthi, R. Material waste management in construction industries. International Journal of Science and Engineering Research (IJOSER). 2015, Vol. 3 No. 5, pp. 1-12.

- Oliveira, K.E.d.S. , da Cal Seixas, S.R. Waste Diversion and Sustainability. In: Leal Filho, W. (eds) Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education. Springer, Cham., 2019, pp.1-12. [CrossRef]

- Chileshe, N. , Zuo, J., Pullen, S., Zillante, G.: Fapohunda, J. Construction Management and the State of Zero Waste. Designing for Zero Waste: Consumption, Technologies and the Built Environment. In book: Designing for Zero Waste: Consumption, Technologies and the Built Environment Chapter: 14. Earthscan. 2012, pp. 2-14.

- Zaman, A. Zero-Waste: A New Sustainability Paradigm for Addressing the Global Waste Problem. In: Edvardsson Björnberg, K., Belin, MÅ., Hansson, S.O., Tingvall, C. (eds) The Vision Zero Handbook. Springer, Cham. Pp. 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Jessica, F. Green & Raúl Salas Reyes. The history of net zero: can we move from concepts to practice? Climate Policy. 2023, pp 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A. A strategic framework for working toward zero waste societies based on perceptions surveys. Recycling. 2017, 2(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A. , Brandt, J., Widerberg, O., Chan, S., & Weinfurter, A. Exploring links between national climate strategies and non-state and subnational climate action in nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Climate Policy. 2019, 20(4), 443–457. [CrossRef]

- Tandon, N. Creating “zero-waste campuses”. In Sustainable waste management: Policies and case studies: 7th IconSWM—ISWMAW. 2020, volume 1 (pp. 183–186). Springer Singapore. [CrossRef]

- C40 Cities. (2020). Advancing towards zero waste declarations. C40 Cities. Available in: https://www.c40.org/other/zero-waste-declaration. (Accessed on 12th December 2024). 20 December.

- Lu, W.H., Yuan. A framework for understanding waste management studies in construction. Waste Management, 2011, 31(6) pp. 1252-1260. [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, W. , Jeberg, S., Alex, J., Johnsen, W., Gurau, B., Lindquist, E. Net Zero Waste: Issues, Technologies, Trends, and Commercially Viable Solutions. In: Goodsite, M., Juhola, S. (eds) Green Defense Technology. NATO Science for Peace and Security Series C: Environmental Security. Springer, Dordrecht. 2017, pp. 4-8. [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A.U.; Lehmann, S. Urban growth and waste management optimization towards ‘zero waste city’. City Cult. Soc. 2011, 2, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmani, M. Design waste mapping: a project life cycle approach. Proc. ICE Waste Resour. Manag. 2013, 166, 114e127, pp.1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, T. and Williams, I.D. A zero-waste vision for industrial networks in Europe. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2012, 207–208, pp.3–7. [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A.U.; Lehmann, S. The zero waste index: A performance measurement tool for waste management systems in a “zero waste city”. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saima, H. , Bhat, M.S., Muzaffar, A.B. Zero Waste: A Sustainable Approach for Waste Management. In book: Innovative Waste Management Technologies for Sustainable Development. 2020, (8) pp. 134-155. [CrossRef]

- Osmani, M. Construction Waste. In Letcher T M and Vallero D A, editors. Waste: A handbook for management, Oxford, Elsevier, 2011, p. 207-218. [CrossRef]

- Osmani, M. Construction Waste Minimization in the UK: Current Pressures for Change and Approaches. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2011, 40, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahankoob, A. , Khoshnava, S.M., Rostami, R., Preece, C. BIM perspectives on construction waste reduction. Management in Construction Research Association (MiCRA) Postgraduate Conference, 2012, pp. 195–199.

- Laovisutthichai, V. , Lu, W., & Bao, Z. Design for construction waste minimization: guidelines and practice. Architectural Engineering and Design Management, 2020, 18(3), pp. 279–298. [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, P.S. , Ambika. S. Chapter 13—Solid waste management through the concept of zero waste. In Book Series: Trends to Approaching Zero Waste, Elsevier, 2022, pp. 293-318. [CrossRef]

- Ganiyu, S. A. , Oyedele, L. O., Akinade, O., Owolabi, H., Akanbi, L., & Gbadamosi, A. BIM competencies for delivering waste-efficient building projects in a circular economy. Developments in the Built Environment. 2020, 4, 100036 pp. 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yean Yng Ling, F. and Song Anh Nguyen, D. Strategies for construction waste management in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Built Environment Project and Asset Management, 2013, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 141-156. [CrossRef]

- Soharu, A. , Naveen BP, Sil, A. An Approach Towards Zero-Waste Building Construction. In: Gupta, A.K., Shukla, S.K., Azamathulla, H. (eds) Advances in Construction Materials and Sustainable Environment. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, 2022, vol 196. Springer, Singapore, pp. 16-20. [CrossRef]

- Abarca-Guerrero, L.; Lobo-Ugalde, S.; Méndez-Carpio, N.; Rodríguez-Leandro, R.; Rudin-Vega. V. Zero Waste Systems: Barriers and Measures to Recycling of Construction and Demolition Waste. Sustainability. 2022, 14, 15265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirelli, D. , & Besana, D. Moving toward Net Zero Carbon Buildings to Face Global Warming: A Narrative Review. Buildings. 2023, 13(3), 684. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z. , & Kim, S. Progress in Research on Net-Zero-Carbon Cities: A Literature Review and Knowledge Framework. Energies. 2023, 16(17), 6279. [CrossRef]

- Akinade, O.O. , Oyedele, L.O., Ajayi, S.O., Bilal, M., Alaka, H.A., Owolabi, H.A. and Arawomo, O.O. Designing out construction waste using BIM technology: Stakeholders’ expectations for industry deployment. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2018, 180, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Osmani, M.; Demian, P.; Baldwin, A. N. The potential use of BIM to aid construction waste minimalisation. In Proceedings of the CIB W78-W102 2011: International Conference –Sophia Antipolis, France, 2011, 26-28 October, pp. 1-11.

- Zaman, A.U.; Lehmann, S. Urban growth and waste management optimization towards ‘zero waste city’. City Cult. Soc. 2011, 2, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Net zero waste from buildings—Rau’s IAS. Retrieved 29th November 2024. https://compass.rauias.com/current-affairs/net-zero-waste-from-buildings.

- Awasthi, A.K. , Cheela, V.S., D’Adamo, I., Iacovidou, E., Islam, M.R., Johnson, M.,... & Li, J. Zero waste approach towards a sustainable waste management. Resources, Environment and Sustainability, 2021, 3, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z. The zero-waste city: case study of Port Louis, Mauritius. Int J Sustain Build Technol Urban Dev., 2018, 9:110–123. [CrossRef]

- Zero Waste South Australia. Better Practice Guide Waste Management for Residential and Mixed Use Development. Available online: http://www.zerowaste.sa.gov.au/about-us (accessed on 31 November 2024).

- Duan, Z. , & Kim, S. Progress in Research on Net-Zero-Carbon Cities: A Literature Review and Knowledge Framework. Energies, 2023, 16(17), 6279. [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, S. Urban Metabolism and the Zero Waste City: Transforming Cities through Sustainable Design and Behaviour Change. Green Cities for Asia and the Pacific; Lindfield, M., Steinberg, F., Eds.; ADB Publication Unit: Manila, Philippines, 2012; Available online: http://www.adb.org/publications/green-cities (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Barbhuiya, M.R. , Kulkarni, K. Use of IoT in Net-Zero Smart City Concept in the Indian Context: A Bibliographic Analysis of Literature. In: Nath Sur, S., Balas, V.E., Bhoi, A.K., Nayyar, A. (eds) IoT and IoE Driven Smart Cities. EAI/Springer Innovations in Communication and Computing. Springer, 2022, Cham, pp. 2-4. [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A. , & Ahsan, T. Zero-waste: Reconsidering waste management for the future. Routledge. 2019, pp. 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Jelonek, D. , Walentek, D. Exemplifying the Zero Waste Concept in smart cities. Economics and Environment, 2022, 81(2), pp. 40-57. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, R. A. , Singh, D. V., Qadri, H., Dar, G. H., Dervash, M. A., Bhat, S. A., Unal, B. T., Ozturk, M., Hakeem, K. R., & Yousaf, B. Vulnerability of municipal solid waste: An 36 S. M. Geelani and A. Haji emerging threat to aquatic ecosystems. Chemosphere, 2021, 287, 132223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, Z. , Zubair, M.O., Humaira. A Comprehensive Review on the Development of Zero Waste Management. In: Bhat, R.A., Dar, G.H., Hajam, Y.A. (eds) Zero Waste Management Technologies. Springer, Cham, 2024, pp. 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Song, Q. , Li, J., Zeng, X. Minimizing the increasing solid waste through zero waste strategy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2015, 104: 199–210. [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, AK. Zero Waste: A potential strategy for sustainable waste management. Waste Management & Research. 2023, 2023;41(6):1061-1062. [CrossRef]

- Sacks, R. , Koskela, L., Dave, B. A., and Owen, R. Interaction of lean and building information modeling in construction. Journal of construction engineering and management, 2010, 136(9), pp. 968-980. [CrossRef]

- Eze, E.C. , Aghimien, D.O., Aigbavboa, C.O. and Sofolahan, O. (2024). Building information modelling adoption for construction waste reduction in the construction industry of a developing country. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 2024, Vol. 31 No. 6, pp. 2205-2223. [CrossRef]

- Jernigan, F.E. BIG BIM—little BIM: the practical approach to building information modeling: integrated practice done the right way! 2nd edition. 4 Site Press, Salisbury, MD; USA, 2008, pp. 56.

- Crotty, R. The Impact of Building Information Modelling: Transforming Construction. Spon Press, London, 2012, pp. 12. [CrossRef]

- Borrmann, A. , König, M., Koch, C., Beetz, J. Building Information Modeling: Why? What? How? In: Borrmann, A., König, M., Koch, C., Beetz, J. (eds) Building Information Modeling. Springer, Cham, 2018, pp. 24. [CrossRef]

- Aftab, U. , Jaleel, F., Aslam, M., Haroon, M., Mansoor, R. Building Information Modeling (BIM) Application in Construction Waste Quantification—A Review. Engineering Proceedings, 2024, 75(1), 8, pp. 1-8.

- Zhang, S. , Tang, Y., Zou, Y. et al. Optimization of architectural design and construction with integrated BIM and PLM methodologies. Sci Rep, 2024, 14, 26153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.M. , Osmani, P., Demian, P., Baldwin, A. A BIM-aided construction waste minimisation framework. Automation in Construction, 2015, Vol. 59, pp. 1–23.

- Li, L.; et al. Developing a BIM-enabled building lifecycle management system for owners: Architecture and case scenario. Automation in Construction. 2021, Vol. 129, 103814, pp. 7. [CrossRef]

- Karolyfi, K. , Szep, J. Ajtayné Károlyfi K, Szép J. A Parametric BIM Framework to Conceptual Structural Design for Assessing the Embodied Environmental Impact. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11990. [CrossRef]

- Bloomberg, M.R. , Burney, D.J., Resnick, D. Building Information Modeling Site Safety Submission Guidelines and Standards. BIM Guidelines: New York City Department of Design and Construction, New York City, USA, 2012, pp. 1-41.

- Won, J. , & Cheng, J. C. Identifying potential opportunities of building information modeling for construction and demolition waste management and minimization. Automation in Construction. 2017, 79, pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, A. , Poon, C.S., Shen, L.Y., Austin, S.A., Wong, I. Modeling design information to evaluate prefabricated and pre-cast design solutions for reducing construction waste in high rise residential buildings. Automation in Construction. 2008, 17, pp. 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C. , Ma, L.Y. A BIM-based system for demolition and renovation waste estimation and planning. Waste Management, 2013. 33(6) pp. 1539-1551. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C. , Won, J. and Das, M. Construction and demolition waste management using BIM technology. In: Proc. 23rd Ann. Conf. of the Int’l. Group for Lean Construction. Perth, Australia, July 29-31, 2015, pp. 381-390.

- Wang J, Li, Z. , Tam, V.W. Critical Factors in Effective Construction Waste Minimization at The Design Stage: A Shenzhen Case Study China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 82, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svalestuen, F. , Knotten, V., Lædre, O., Drevland, F., Lohne, J. Using building information model (BIM) devices to improve information flow and collaboration on construction sites. Journal of Information Technology in Construction (ITcon), 2017, 22(11), pp. 204-219.

- Rajendran, P. , Gomez, C.P. Implementing BIM for Waste Minimization in the Construction Industry: A Literature Review. The 2nd International Conference on Management, Malaysia, 2012, pp. 557-570.

- Akbarnezhad, A. , Ong, K.C., Chandra, L.R. Economic and environmental assessment of deconstruction strategies using building information modeling. Automation in Construction, 2014, 37, pp. 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinade, O.O. , Oyedele, L.O., Munir, K., Bilal, M., Ajayi, S.O., Owolabi, H.A., Alaka, H.A. and Bello, S.A. Evaluation criteria for construction waste management tools: towards a holistic BIM framework. International Journal of Sustainable Building Technology and Urban Development. 2016, 7(1), pp.3-21. [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.J. , Livesey, P. , Wang, J. et al. Deconstruction waste management through 3d reconstruction and bim: a case study. Vis. in Eng. 2017, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arayici, Y. , Coates, P., Koskela, L., Kagioglou, M., Usher, C., and O’reilly, K. Technology adoption in the BIM implementation for lean architectural practice. Technology adoption in the BIM implementation for lean architectural practice. Automation in construction. 2011, 20(2), 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W. , Webster, C., Chen, K., Zhang, X., & Chen, X. Computational Building Information Modelling for construction waste management: Moving from rhetoric to reality. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2017, 68, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, S. Building information modeling (BIM): Trends, benefits, risks, and challenges for the AEC industry. Leadership and Management in Engineering. 2011, pp. 14. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M. , Shafiq, N., Al-Mekhlafi, A. -B. A., Al-Fakih, A., Zawawi, N. A., Mohamed, A. M., Khallaf, R., Abualrejal, H. M., Shehu, A. A., & Al-Nini, A. Beneficial Effects of 3D BIM for Pre-Empting Waste during the Planning and Design Stage of Building and Waste Reduction Strategies. Sustainability. 2022, 14(6), 3410. [CrossRef]

- Karanafti, A. , Trubina, N., Giarma, C., Tsikaloudaki, K., Theodosiou, T. Integrating BIMs in Construction and Demolition Waste Management for Circularity Enhancement-A Review. In: Ungureanu, V., Bragança, L., Baniotopoulos, C., Abdalla, K.M. (eds) 4th International Conference “Coordinating Engineering for Sustainability and Resilience” & Midterm Conference of CircularB “Implementation of Circular Economy in the Built Environment”. CESARE 2024. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, 2024, vol 489. Springer, Cham.

- Cao, D. , Wang, G., Li, H., Skitmore, M., Huang, T., Zhang, W. Practices and effectiveness of building information modelling in construction projects in China. Automation in Construction. 2015, Vol. 49, pp. 113-122.

- Curran, T. , Williams, I. A zero-waste vision for industrial networks in Europe. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, pp. 3-7. [CrossRef]

- Dave, B. Developing a construction management system based on lean construction and building information modeling. PhD Thesis, ., School of Built Environment, Salford University, Salford, UK, 2013; p. 12.

- Burcu, S. , Atacan, A., Nilay, C., Kofi, A. Construction Waste Reduction Through BIM Based Site Management Approach. International journal of engineering technologies. 2017, Vol.3, No.3, pp. 135-142. [CrossRef]

- Eastman, C. , Teicholz, P., Sacks, R. and Liston, K. BIM handbook: A guide to building information modeling for owners, managers, designers, engineers, and contractors. (2nd ed.) Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. 2011, pp. 45-47.

- Azhar, S. Building Information Modelling (BIM): Trends, Benefits, Risks and Challenges for the AEC Industry. Leadership and Management in Engineering. 2011, 11, pp. 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, A. , Watson, P. Construction Management: Principles and Practices. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2004, pp. 34.

- Lu, C.W. , Webster, K., Zhang, C., Chen, X. Computational building information modelling for construction waste management: Moving from rhetoric to reality. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2017, Vol. 68, pp. 587–595. [CrossRef]

- Mollasalehi, S. , Fleming, A., Talebi, S, and Underwood, J. Development of an Experimental Waste Framework based on BIM/Lean concept in construction design. In: Proc. 24th Ann. Conf. of the Int’l. Group for Lean Construction, Boston, MA, USA, 2016, sect.4 pp. 193–202.

- Olatunji, O.A. , Sher, W.D., Gu, N. Modeling outcomes of Collaboration in Building Information Modelling through theory lenses. In I. Wallis, L. Bilan, M. Smith and A.S. (eds)Sustainable Construction: Industrialized, Integrated, 13CON handbook, 2010, pp. 47-50.

- Won, J. , Cheng, C.P., Lee, G. Quantification of construction waste prevented by BIM based design validation: Case studies in South Korea. Waste Management. 2016, Vol. 49, pp.170–180. [CrossRef]

- Yean Yng Ling, F. and Song Anh Nguyen, D. Strategies for construction waste management in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Built Environment Project and Asset Management. 2013, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 141-156. [CrossRef]

- Obi, L, Awuzie, B., Obi, C., Omotayo, T.S., Oke, A., Osobajo, O. BIM for deconstruction: an interpretive structural model of factors influencing implementation. Buildings 2021, 11(6), pp. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Han, D. , Kalantari, M., Rajabifard, A. Building information modeling (BIM) for construction and demolition waste management in Australia: a research agenda. Sustainability 2021, 13(23). [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. , Jha, K.N., Vyas, G. Proposing building information modeling-based theoretical framework for construction and demolition waste management: strategies and tools. Int J Constr Manage. 2022, 22(12):2345–2355. [CrossRef]

- Kang, K. , Besklubova S., Dai, Y., Zhong, R.Y. Building demolition waste management through smart BIM: a case study in Hong Kong. Waste Management. 2022, 143:69–83. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q. , Zhang, Y., Li, Z., Shi, W., Wang, J., Sun, Y., Xu, L. and Wang, X. A review of integrated applications of BIM and related technologies in whole building life cycle. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management. 2020, Vol. 27 No. 8, pp. 1647-1677. [CrossRef]

- Hai, Y. , Yang, L., Sepasgozar, S. BIM Applications in Waste and Demolition Management in Circular Economy Concept. Environmental Sciences Proceedings. 2021; 12(1):13. [CrossRef]

- Mrema, S.A. , Lau, H.H., Liew, S.C., Ekambaram, P., Alam, M., Lee, V.C. Building Information Modeling (BIM) for Construction and Demolition Waste (CDW) Management: Scientometric and State-of-the-Art Review. In: Choo, C.S., Wong, B.T., Sharkawi, K.H.B., Kong, D. (eds) Proceedings of ASEAN-Australian Engineering Congress (AAEC2022). AAEC 2022. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering, 2023, vol 1072. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Sutton, A. , Clowes, M., Preston, L., Booth, A. Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements. HealthInfoLibrJ. 2019, 36:202–22. [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T. , Thorne, S., Malterud, K., Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? EurJClinInvest. 2018, 48:e12931. [CrossRef]

- Erin, S.B. , Jerusalem M., Lara, V. State-of-the-art literature review methodology: A six-step approach for knowledge synthesis. Perspect Med Edu. 2021, pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).