Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

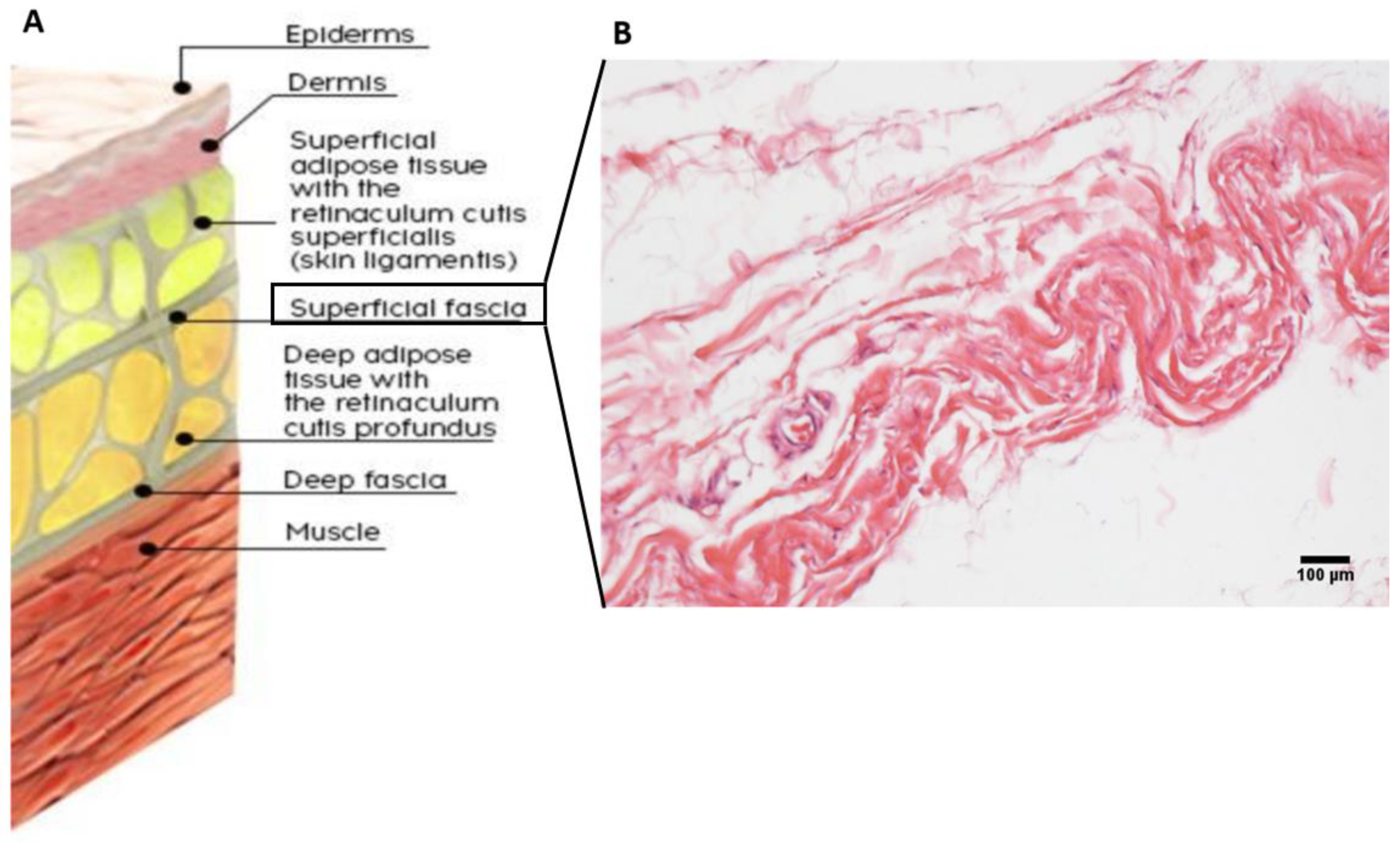

2.1. Thickness of the Superficial Fascia

2.2. The Cellular Population

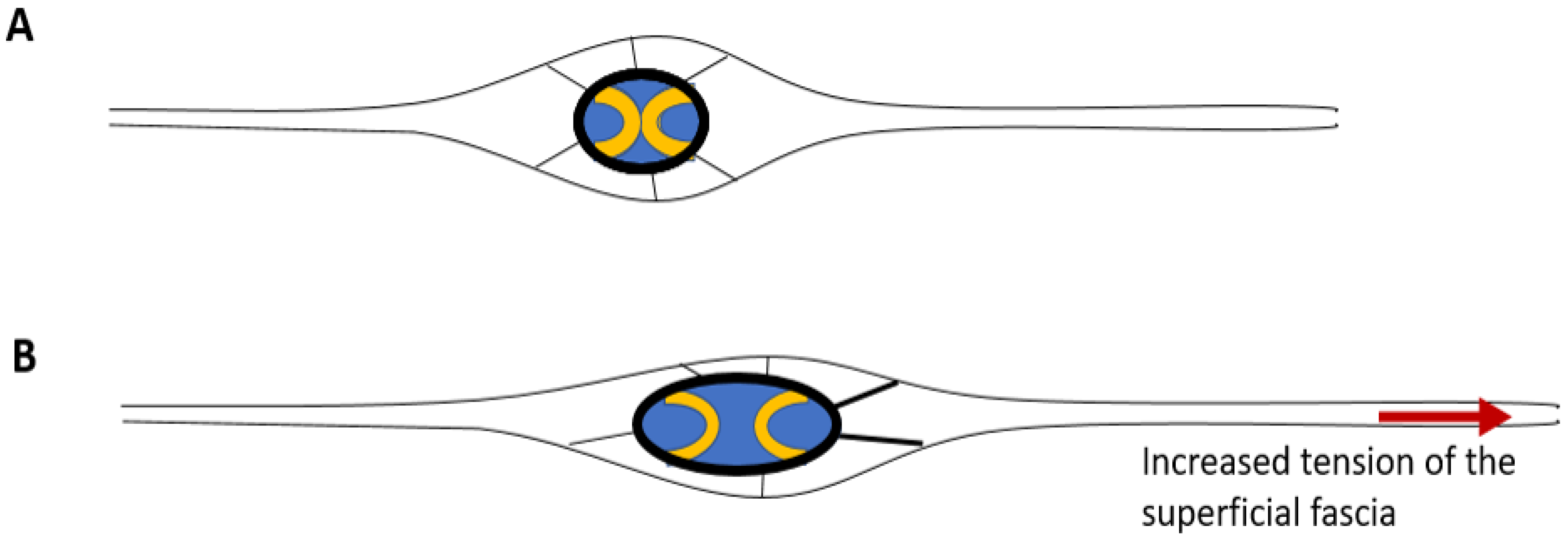

2.3. Fibrous Component of the Superficial Fascia

2.4. Innervation

2.5. Blood Supply and Limphatyc Net of the Superficial Fascia

2.6. Pathological Implications

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stecco, C.; Adstrum, S.; Hedley, G.; Schleip, R.; Yucesoy, C.A. Update on fascial nomenclature. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2018;22(2):354. [CrossRef]

- Adstrum, S.; Hedley, G.; Schleip, R.; Stecco, C.; Yucesoy, C.A. Defining the fascial system. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2017;21(1):173-177. [CrossRef]

- Stecco, C.; Schleip, R. A fascia and the fascial system. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2016;20(1):139-140. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.; Duong, H. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Scarpa Fascia. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; August 7, 2023.

- Bordoni, B.; Mahabadi, N.; Varacallo, M. Anatomy, Fascia. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; July 17, 2023.

- Ullah, S.M.; Grant, R.C.; Johnson, M.; McAlister, V.C. Scarpa's fascia and clinical signs: the role of the membranous superficial fascia in the eponymous clinical signs of retroperitoneal catastrophe. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2013;95(7):519-522. [CrossRef]

- Chopra, J.; Rani, A.; Rani, A.; Srivastava, A.K.; Sharma, P.K. Re-evaluation of superficial fascia of anterior abdominal wall: a computed tomographic study. Surg Radiol Anat. 2011;33(10):843-849. [CrossRef]

- Putterman, A.M. Deep and superficial eyelid fascia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(4):721e-723e. [CrossRef]

- Graca Neto, L.; Graf, R.M. Anatomy of the Superficial Fascia System of the Breast: A Comprehensive Theory of Breast Fascial Anatomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145(1):193e-194e. [CrossRef]

- Rehnke, R.D.; Groening, R.M.; Van Buskirk, E.R.; Clarke, J.M. Anatomy of the Superficial Fascia System of the Breast: A Comprehensive Theory of Breast Fascial Anatomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142(5):1135-1144. [CrossRef]

- Yaghan, R.J.; Heis, H.A.; Lataifeh, I.M.; Al-Khazaaleh, O.A. Herniation of part of the breast through a congenital defect of the superficial fascia of the anterior thoracic wall. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32(3):566-568. [CrossRef]

- Stecco, C. Functional atlas of the human fascial system, 1st ed.; 2015, Churchill Linvingston, Elsevier: London, UK, 2015. ISBN 978-070-204-430-4.

- Rohrich, R.J.; Pessa, J.E. The retaining system of the face: histologic evaluation of the septal boundaries of the subcutaneous fat compartments. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 May;121(5):1804-1809. [CrossRef]

- Han, A.; Inoue, E.; Kikuchi, K.; Haikata, Y.; Tabira, Y.; Iwanaga, J.; Saga, T.; Kiyokawa, K.; Watanabe, K. Gross anatomical study of the subcutaneous structures that create the three-dimensional shape of the buttocks. Clin Anat. 2023 Mar;36(2):297-307. [CrossRef]

- Stecco, C.; Pirri, C.; Fede, C.; Fan, C.; Giordani, F.; Stecco, L.; Foti, C.; De Caro, R. Dermatome and fasciatome. Clin Anat. 2019;32(7):896-902. [CrossRef]

- Wilke, J.; Tenberg, S. Semimembranosus muscle displacement is associated with movement of the superficial fascia: An in vivo ultrasound investigation. J Anat. 2020;237(6):1026-1031. [CrossRef]

- Di Taranto, G.; Cicione, C.; Visconti, G.; Isgrò, M.A.; Barba, M.; Di Stasio, E.; Stigliano, E.; Bernadini, C.; Michetti, F.; Salgarello, M.; et al. Qualitative and quantitative differences of adipose-derived stromal cells from superficial and deep subcutaneous lipoaspirates: a matter of fat. Cytotherapy. 2015;17(8):1076-1089. [CrossRef]

- Si, L.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, M.; Chen, X.; Yu, L.; Wang, H.C.; Wang, Y. The Superficial Fascia System: Anatomical Guideline for Zoning in Liposuction-Assisted Back Contouring. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023 May 1;151(5):989-998. [CrossRef]

- Lancerotto, L.; Stecco, C.; Macchi, V.; Porzionato, A.; Stecco, A.; De Caro, R. Layers of the abdominal wall: anatomical investigation of subcutaneous tissue and superficial fascia. Surg Radiol Anat. 2011 Dec;33(10):835-42. [CrossRef]

- Pessa, J.E. SMAS Fusion Zones Determine the Subfascial and Subcutaneous Anatomy of the Human Face: Fascial Spaces, Fat Compartments, and Models of Facial Aging. Aesthet Surg J. 2016 May;36(5):515-26. [CrossRef]

- Pirri, C.; Fede, C.; Petrelli, L.; Guidolin, D.; Fan, C.; De Caro, R.; Stecco, C. An anatomical comparison of the fasciae of the thigh: A macroscopic, microscopic and ultrasound imaging study. J Anat. 2021 Apr;238(4):999-1009. [CrossRef]

- Pirri, C.; Stecco, C.; Petrelli, L.; De Caro, R.; Özçakar, L. Reappraisal on the Superficial Fascia in the Subcutaneous Tissue: Ultrasound and Histological Images Speaking Louder Than Words. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022 Jul 1;150(1):244e-245e. [CrossRef]

- Hammoudeh, D.S.N.; Dohi, T.; Cho, H.; Ogawa, R. In Vivo Analysis of the Superficial and Deep Fascia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022 Nov 1;150(5):1035-1044. [CrossRef]

- Pirri, C.; Pirri, N.; Guidolin, D.; Macchi, V.; De Caro, R.; Stecco, C. Ultrasound Imaging of the Superficial Fascia in the Upper Limb: Arm and Forearm. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022 Aug 4;12(8):1884. [CrossRef]

- Gatt, A.; Agarwal, S.; Zito, P.M. Anatomy, Fascia Layers. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; July 24, 2023.

- Abu-Hijleh, M.F.; Roshier, A.L.; Al-Shboul, Q.; Dharap, A.S.; Harris, P.F. The membranous layer of superficial fascia: evidence for its widespread distribution in the body. Surg Radiol Anat. 2006 Dec;28(6):606-19. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.K.; Kumar, P.; Aithal, S.K.; Kotian, S.R.; Thittamaranahalli, H.; Bangera, H.; Prasad, K.; Souza, A.D. Histological and biochemical study of the superficial abdominal fascia and its implication in obesity. Anat Cell Biol. 2016 Sep;49(3):184-188. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Pandey, A.K.; Kumar, B.; Aithal, S.K. Anatomical study of superficial fascia and localized fat deposits of abdomen. Indian J Plast Surg. 2011 Sep;44(3):478-83. [CrossRef]

- Matousek, S.A.; Corlett, R.J.; Ashton, M.W. Understanding the fascial supporting network of the breast: key ligamentous structures in breast augmentation and a proposed system of nomenclature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014 Feb;133(2):273-281. [CrossRef]

- Komiya, T.; Ito, N.; Imai, R.; Itoh, M.; Naito, M.; Matsubayashi, J.; Matsumura, H. Anatomy of the superficial layer of superficial fascia around the nipple-areola complex. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2015 Apr;39(2):209-13. [CrossRef]

- Nava, M.; Quattrone, P.; Riggio, E. Focus on the breast fascial system: a new approach for inframammary fold reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998 Sep;102(4):1034-45. [CrossRef]

- Fede, C.; Pirri, C.; Fan, C.; Petrelli, L.; Guidolin, D.; De Caro, R.; Stecco, C. A Closer Look at the Cellular and Molecular Components of the Deep/Muscular Fasciae. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(3):1411. Published 2021 Jan 30. [CrossRef]

- Langevin, H.M.; Cornbrooks, C.J.; Taatjes, D.J. Fibroblasts form a body-wide cellular network. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;122(1):7-15. [CrossRef]

- Baptista, L.S.; Côrtes, I.; Montenegro, B.; Claudio-da-Silva, C.; Bouschbacher, M.; Jobeili, L.; Auxenfans, C.; Sigaudo-Roussel, D. A novel conjunctive microenvironment derived from human subcutaneous adipose tissue contributes to physiology of its superficial layer. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021 Aug 28;12(1):480. [CrossRef]

- Fede, C.; Petrelli, L.; Pirri, C.; Tiengo, C.; De Caro, R.; Stecco, C. Detection of Mast Cells in Human Superficial Fascia. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Jul 18;24(14):11599. [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.M.; Barreda, D.R. Acute Inflammation in Tissue Healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 641.

- Watanabe, K.; Han, A.; Inoue, E.; Iwanaga, J.; Tabira, Y.; Yamashita, A.; Kikuchi, K.; Haikata, Y.; Nooma, K.; Saga, T. The Key Structure of the Facial Soft Tissue: The Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System. Kurume Med J. 2023 Jul 3;68(2):53-61. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.M.; Hochman, B.; Locali, R.F.; Rosa-Oliveira L.M. A stratigraphic approach to the superficial musculoaponeurotic system and its anatomic correlation with the superficial fascia. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2006 Sep-Oct;30(5):549-52. [CrossRef]

- Stecco, C.; Macchi, V.; Porzionato, A.; Duparc, F.; De Caro, R. The fascia: the forgotten structure. Ital J Anat Embryol. 2011;116(3):127-38.

- Hwang, K.; Kim, H.; Kim, D.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Kang, Y.H. Superficial Fascia (SF) in the Cheek and Parotid Area: Histology and Magnetic Resonance Image (MRI). Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2016 Aug;40(4):566-77. [CrossRef]

- Pirri, C.; Fede, C.; Petrelli, L.; Guidolin, D.; Fan, C.; De Caro, R.; Stecco, C. Elastic Fibres in the subcutaneous tissue: Is there a difference between superficial and muscular fascia? A cadaver study. Skin Res Technol. 2022 Jan;28(1):21-27. [CrossRef]

- Berardo, A.; Bonaldi, L.; Stecco, C.; Fontanella, C.G. Biomechanical properties of the human superficial fascia: Site-specific variability and anisotropy of abdominal and thoracic regions. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2024 Sep;157:106637. [CrossRef]

- Hollinsky, C.; Sandberg, S. Measurement of the tensile strength of the ventral abdominal wall in comparison with scar tissue. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2007 Jan;22(1):88-92. [CrossRef]

- Fede, C.; Porzionato, A.; Petrelli, L.; Fan, C.; Pirri, C.; Biz, C.; De Caro, R.; Stecco, C. Fascia and soft tissues innervation in the human hip and their possible role in post-surgical pain. J Orthop Res. 2020 Jul;38(7):1646-1654. [CrossRef]

- Fede, C.; Petrelli, L.; Pirri, C.; Neuhuber, W.; Tiengo, C.; Biz, C.; De Caro, R.; Schleip, R.; Stecco, C. Innervation of human superficial fascia. Front Neuroanat. 2022 Aug 29;16:981426. [CrossRef]

- Neuhuber, W.; and Jänig, W. Fascia in the Osteopathic Field, eds T. Liem, P. Tozzi, A. Chila. Scotland: Handspring Publishing Limited. 2017. ISBN 978-882-144-729-7.

- Larsson, M.; Nagi, S.S. Role of C-tactile fibers in pain modulation: animal and human perspectives. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 43, 2022, 138–144. [CrossRef]

- Staubesand, J.; Li, Y. (1996). Zum Feinbau der Fascia cruris mit besonderer Beruücksichtigung epi- und intrafaszialer Nerven. Manuelle Medizin 34, 1996, 196–200.

- Schleip, R.; Gabbiani, G.; Wilke, J.; Naylor, I.; Hinz, B.; Zorn, A.; Jäger, H.; Breul, R.; Schreiner, S.; Klingler, W. Fascia Is Able to Actively Contract and May Thereby Influence Musculoskeletal Dynamics: A Histochemical and Mechanographic Investigation. Front Physiol. 2019;10:336. [CrossRef]

- Pirri, C.; Petrelli, L.; Fede, C.; Guidolin, D.; Tiengo, C.; De Caro, R.; Stecco, C. Blood supply to the superficial fascia of the abdomen: An anatomical study. Clin Anat. 2023 May;36(4):570-580. [CrossRef]

- Tao, K.Z.; Chen, E.Y.; Ji, R.M.; Dang, R.S. Anatomical study on arteries of fasciae in the forearm fasciocutaneous flap. Clin Anat. 2000;13(1):1-5. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, Z.P.; Sun, Y.; Li, L.C.; Liu, Y.Q.; Yang, Y.R.; Qi, L.N.; Yang, J.H.; Shi, Y.T.; Qin, X.Z. More potential uses of specific perforator flaps in the calf - A cadaveric study on the subdermal vascular structure of the lower leg. Ann Anat. 2024 Jun;254:152262. [CrossRef]

- Albertin, G.; Astolfi, L.; Fede, C.; Simoni, E.; Contran, M.; Petrelli, L.; Tiengo, C.; Guidolin, D.; De Caro, R.; Stecco, C. Detection of Lymphatic Vessels in the Superficial Fascia of the Abdomen. Life (Basel). 2023 Mar 20;13(3):836. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, T.; Coon, D.; Kanbour-Shakir, A.; Michaels, J.5th; Rubin, J.P. Defining the lymphatic system of the anterior abdominal wall: an anatomical study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Apr;135(4):1027-1032. [CrossRef]

- Würinger, E. Localization of Central Breast Lymphatics and Predefined Separation of Lobes along the Horizontal Septum. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2023 Dec 7;11(12):e5446. [CrossRef]

- Whipple, L.A.; Fournier, C.T.; Heiman, A.J.; Awad, A.A.; Roth, M.Z.; Cotofana, S.; Ricci, J.A. The Anatomical Basis of Cellulite Dimple Formation: An Ultrasound-Based Examination. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021 Sep 1;148(3):375e-381e. [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C.; Hladik, C.; Hamade, H.; Frank, K.; Kaminer, M.S.; Hexsel, D.; Gotkin, R.H.; Sadick, N.S.; Green, J.B.; Cotofana, S. Structural Gender Dimorphism and the Biomechanics of the Gluteal Subcutaneous Tissue: Implications for the Pathophysiology of Cellulite. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 Apr;143(4):1077-1086. [CrossRef]

- Cotofana, S.; Kaminer, M.S. Anatomic update on the 3-dimensionality of the subdermal septum and its relevance for the pathophysiology of cellulite. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Aug;21(8):3232-3239. [CrossRef]

- Révelon, G.; Rahmouni, A.; Jazaerli, N.; Godeau, B.; Chosidow, O.; Authier, J.; Mathieu, D.; Roujeau, J.C.; Vasile, N. Acute swelling of the limbs: magnetic resonance pictorial review of fascial and muscle signal changes. Eur J Radiol. 1999 Apr;30(1):11-21. [CrossRef]

- Correa-Gallegos, D.; Rinkevich, Y. Cutting into wound repair. FEBS J. 2022 Sep;289(17):5034-5048. [CrossRef]

- Pirri, C.; Stecco, C.; Pirri, N.; De Caro, R.; Özçakar, L. Ultrasound examination for a heel scar: seeing/treating the painful superficial fascia. Med Ultrason. 2022 May 25;24(2):255-256. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Rinkevich, Y. Furnishing Wound Repair by the Subcutaneous Fascia. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Aug 20;22(16):9006. [CrossRef]

- Idy-Peretti, I.; Bittoun, J.; Alliot, F.A.; Richard, S.B.; Querleux, B.G.; Cluzan, R.V. Lymphedematous skin and subcutis: in vivo high resolution magnetic resonance imaging evaluation. J Invest Dermatol. 1998 May;110(5):782-7. [CrossRef]

- Pirri, C.; Pirri, N.; Ferraretto, C.; Bonaldo, L.; De Caro, R.; Masiero, S.; Stecco, C. Ultrasound Imaging of the Superficial and Deep Fasciae Thickness of Upper Limbs in Lymphedema Patients Versus Healthy Subjects. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024;14(23):2697. [CrossRef]

- Stecco, A.; Stern, R.; Fantoni, I.; De Caro, R.; Stecco, C. Fascial Disorders: Implications for Treatment. PM R. 2016 Feb;8(2):161-8. [CrossRef]

- Stecco, C.; Tiengo, C.; Stecco, A.; Porzionato, A.; Macchi, V.; Stern, R.; De Caro, R. Fascia redefined: anatomical features and technical relevance in fascial flap surgery. Surg Radiol Anat. 2013 Jul;35(5):369-76. [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.S.; Hwang, K.; Lee, S.Y.; Song, J.M.; Kim, H. Forces Required to Pull the Superficial Fascia in Facelifts. Plast Surg (Oakv). 2018 Feb;26(1):40-45. [CrossRef]

- Galant, J.; Martí-Bonmatí, L.; Soler, R.; Saez, F.; Lafuente, J.; Bonmatí, C.; Gonzalez, I. Grading of subcutaneous soft tissue tumors by means of their relationship with the superficial fascia on MR imaging. Skeletal Radiol. 1998 Dec;27(12):657-63. [CrossRef]

- Caggiati, A. Fascial relationships of the long saphenous vein. Circulation. 1999;100(25):2547-2549. [CrossRef]

- Won, E.; Kim, Y.K. Stress, the Autonomic Nervous System, and the Immune-kynurenine Pathway in the Etiology of Depression. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016;14(7):665-73. [CrossRef]

- Lowrance, S.A.; Ionadi, A.; McKay, E.; Douglas, X.; Johnson, J.D. Sympathetic nervous system contributes to enhanced corticosterone levels following chronic stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016;68:163-70. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Caudle, Y.; Wheeler, C.; Zhou, Y.; Stuart, C.; Yao, B.; Yin, D. TGF-β1/Smad2/3/Foxp3 signaling is required for chronic stress-induced immune suppression. J Neuroimmunol. 2018;314:30-41. [CrossRef]

- Evdokimov, D.; Dinkel, P.; Frank, J.; Sommer, C.; Üçeyler, N. Characterization of dermal skin innervation in fibromyalgia syndrome. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0227674. [CrossRef]

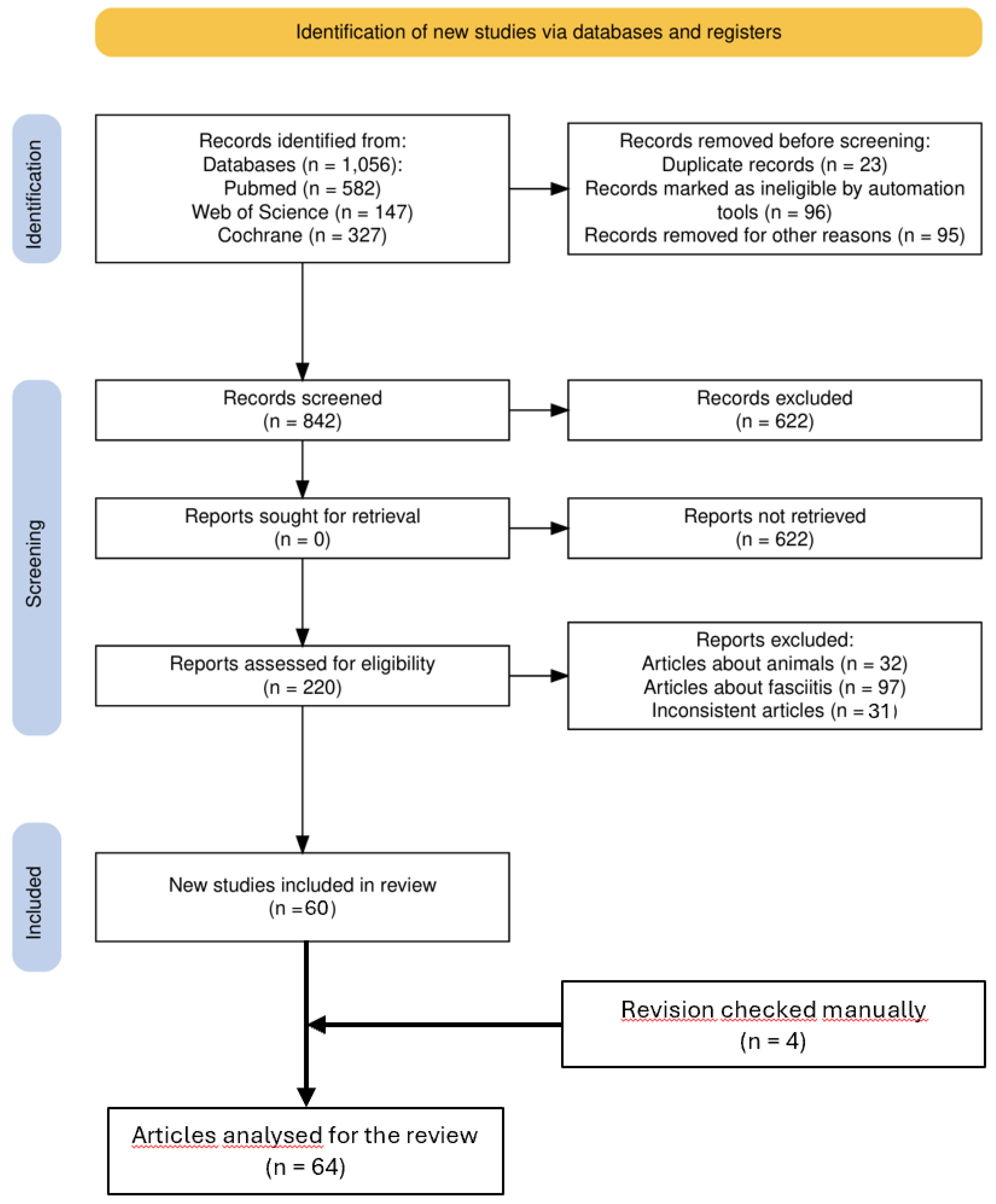

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, n71.

| Region | Mean value | |

|---|---|---|

| Upper limb | Anterior | 400 ± 100 |

| Posterior | 530 ± 100 | |

| Dorsal Trunk | Cranial | 600 to 700 |

| Caudal | 500 to 600 | |

| Abdomen | Cranial | 360 ± 22 ♂ 315 ± 56 ♀ |

| Caudal | 528 ± 38 ♂ 390 ± 36 ♀ |

|

| NAC | 309 ± 171 | |

| Thigh | Anterior | 490 ± 140 |

| Posterior | 500 ± 110 | |

| Medially | 520 ± 100 | |

| Laterally | 420 ± 120 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).