For economic considerations, the deicing salts for highways and bridges are primarily composed of chloride, whereas the erosion of chloride solutions constitutes one of the main contributors to damages on highways and bridges. Chloride ions are detrimental to concrete structures on highways and bridges in two ways [

4]. On the one hand, they crystallize into salt inside cement concrete and expand, causing cement concrete to crack. Chloride ions displace with the calcium hydroxide in cement. Due to the presence of Chloride ions, the CaCl

2 generated is more soluble than Ca (OH)

2. That is, the osmotic pressure of salt solution causes the water inside the concrete to migrate toward the external surface, causing the concrete to expand and crack more rapidly. When the concentration of CaCl

2 in the concrete is high (>15%), it can combine with CaO into very tiny, needle-like crystals in the liquid phase which, when sufficiently accumulated, can lead to expansion and corrosion of the concrete [

5]. Microscopic studies have also demonstrated that Chloride ions can penetrate into concrete and damage the internal structure of gel; presence of high-concentration chloride can intensify the dry shrinkage of concrete [

6,

7]. On the other hand, the use of snow melting agents and deicing salts cause an increase in the Chloride concentration on the surface of highways and bridges. With small radius and high activity, chloride ions can easily penetrate the passivation film of the concrete and cause the reinforcement to rust [

8]. When the chloride content in the solution is high or after repeated dry/welt cycles, more salt will be brought into the concrete. As a result, crystallized salt will produce high crystallization pressure in the concrete pores and cause the concrete surface to spall, crack or crumble, resulting in a shorter service life of the concrete structure than expected by design [

9,

10].

In order to increase the service life of concrete structures, research has been made around green, low carbon and coating protections of concrete materials [

12,

14]. The purpose is to obtain better concrete performance, especially surface protection and maintenance, [

15]. Epoxy coatings comprising primarily of epoxy resin have been developed and widely applied [

16]. The idea behind this treatment is to form a tight physical protection over the concrete surface [

2], so as to prevent aggressive media from coming into the interior of the concrete and increase its durability [

3,

4]. Today, epoxy resin coatings are still the most widely used, most widely applicable and the most important corrosion protection in the world. Surface coating can form a dense watertight layer over the concrete surface and prevent external corrosive media from intrusion. Diamanti et al. [

17] investigated the effect of polymer-modified cementitious coatings of two different polymer-to-cement ratios on the water permeability of concrete and found that epoxy resin coatings as a physical barrier is well able to minimize water intrusion into concrete. Unfortunately, the durability of epoxy resin-cured materials is heavily restricted by their high internal stress, low toughness, ready degradation under high temperature, and poor wet stability [

3,

12,

17]. To solve these problems, Fei Li [

16] prepared a water-based hydrophobic slurry by combining two cost effective, highly available materials, epoxy resin and octadecylamine (ODA), and used it as a binder in o-concrete. They eventually created a superhydrophobic concrete composite (SCC) with a water contact angle of 156° and sliding angle of 8°. Liu [

17] prepared a nano-composite anti-corrosion filler with a mass ratio of CeO2: GO = 4:1 by hydrothermally growing cerium oxide on the surface of graphene oxide. The corrosion resistance of reinforced concrete in the marine environment was effectively improved. Guo et al. [

17] prepared a novel TiO2-graphene modified epoxy resin as a coating for ordinary Portland cement (OPC) concrete. It was found that adding given amounts of TiO2-graphene nanofiller (0.3 % and 0.5 %) greatly improved the impermeability of chloride (as reflected by capillary adsorption and chloride permeability). Silicone, which features Si-O bonds with high bonding energy [

20], has been proved to improve the thermal stability, weather resistance, and brittleness of epoxy resin [

21,

22]. Also, as silicone has low surface free energy, when applied over the surface of epoxy resin, it can enhance the water and oil resistance of the material [

23]. Zheng et al. [

24] prepared a solvent-free, epoxy heavy-duty anticorrosive coating composed of modified epoxy resin, reactive toughening diluent, and other additives and significantly enhanced the material’s resistance to salt spray and corrosion. Qu et al [

23] prepared coated concrete specimens by addingnano-SiO

2 and nano-TiO

2 into epoxy resin coating and subjected them to accelerated aging under ultraviolet irradiation, followed by accelerated carbonation or Coulomb electric flux test. The long-term carbonation and chloride erosion resistance of the coated concrete were significantly improved. Fernández-Álvarez et al. [

26] discovered that SiO

2 nanoparticles can increase the contact angle of cryptic epoxy resin coatings and enhance their resistance to permeation and chloride ion erosion. So far, research has covered many types of anticorrosive coatings, including solvent-based and solvent-free epoxy anticorrosive coatings [

3,

27]. Dorado et al [

26] demonstrated that the most promising adhesion values can be delivered by adding 3 wt% of the synthesized Fe

2O

3 nanoparticles into a graphite carbonaceous matrix; the nano-modified coating displayed much greater resistance to chemical corrosion and surface wear. However, there are some problems pending further studies, such as the cost of nanoparticles and silicone as a modifier, and the weather resistance of rubber-modified epoxy resin [

2,

3,

15].

Engineering practices in northern China have proved that epoxy resin coatings for highway and bridge concrete structures lack sufficient freeze-thaw durability [

29], since aggressive media like hydroxide and Chloride solutions will penetrate through the coating and react with concrete, resulting in gradual failure of the physical protection [

5,

6]. Within the second to third service year of the epoxy resin coating, surface spalling and structural strength degradation will occur to the structure as a result of freezing and thawing processes involving chloride [

30,

31]. This greatly shortens the maintenance cycle and increases the maintenance workload, bringing additional labor and material costs [

32,

33]. It is therefore very necessary to improve epoxy resin products and make the concrete coating more durable, especially in seasonally frozen areas where highway concrete structures are exposed to erosion induced by snow melting agents.

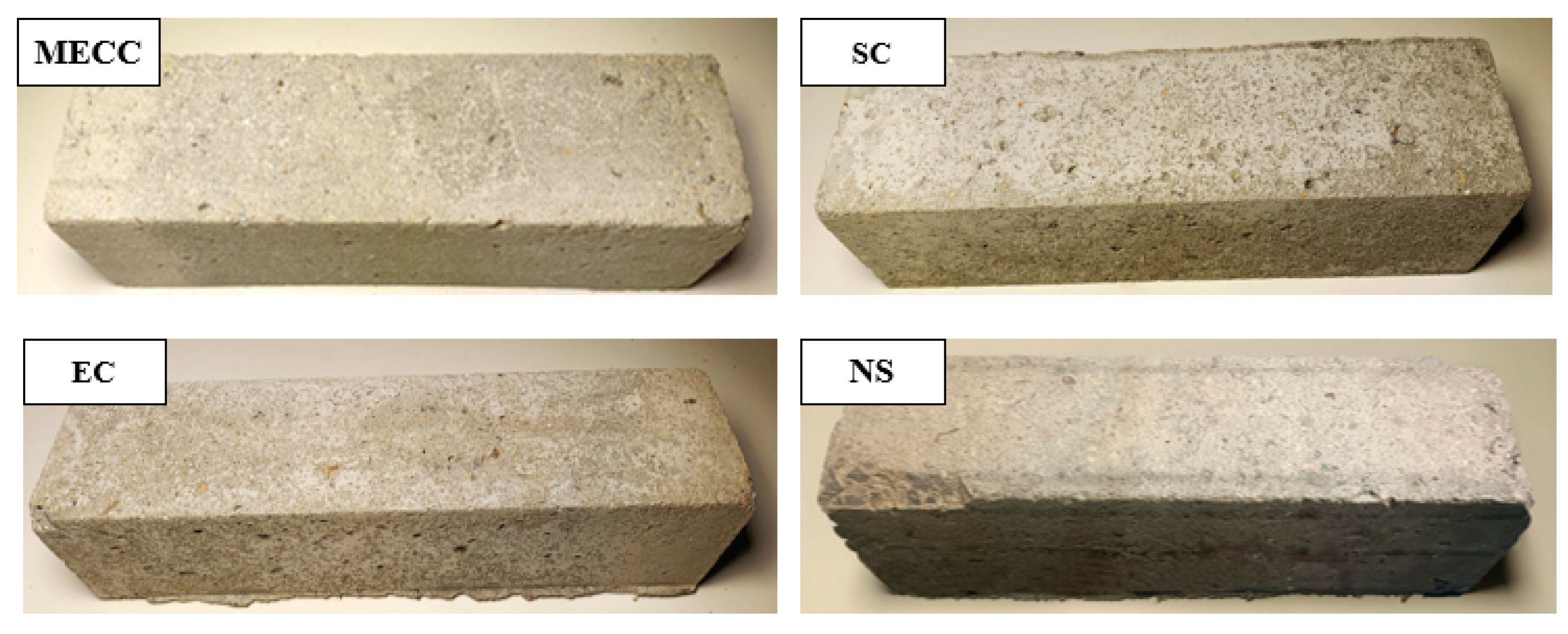

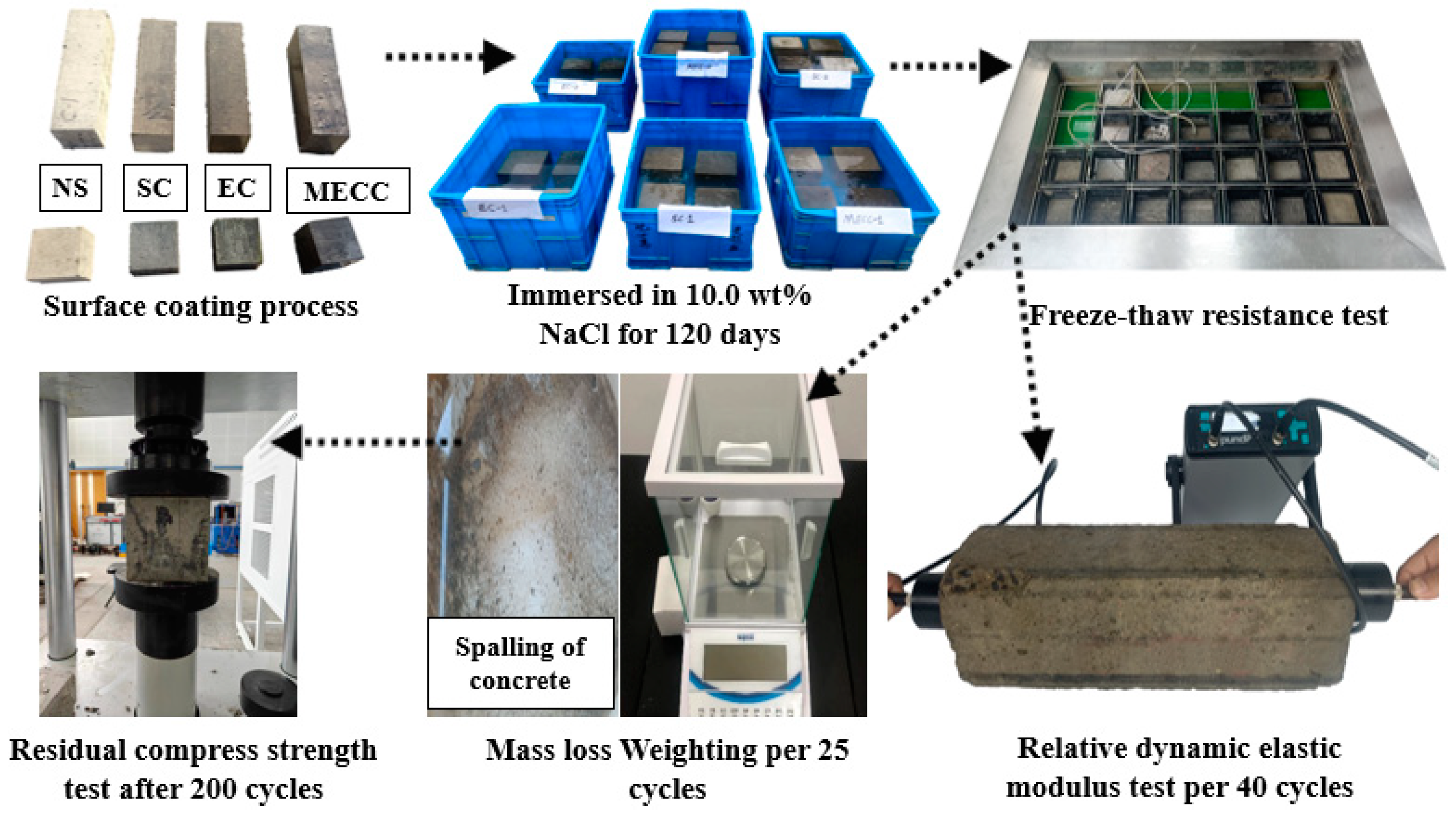

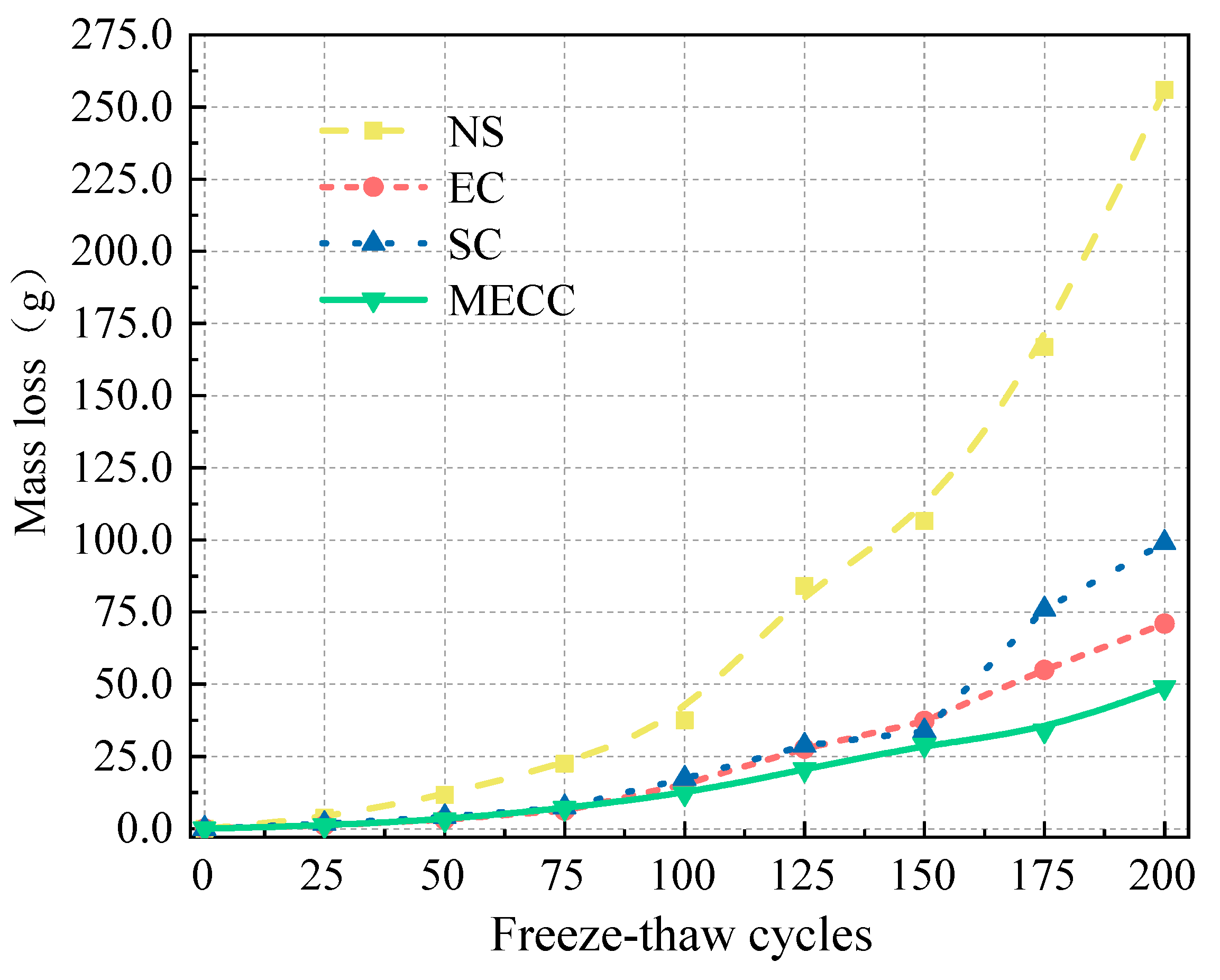

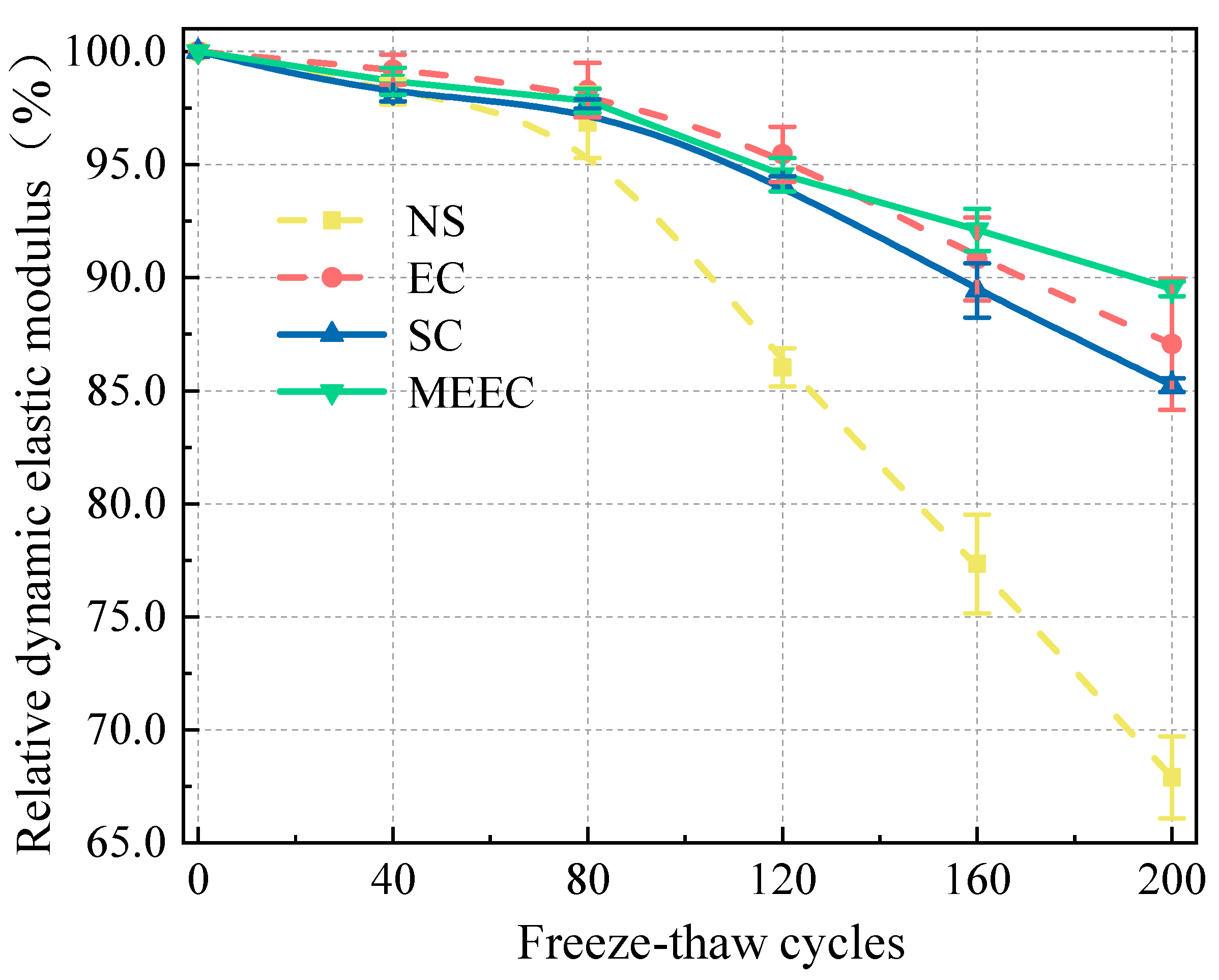

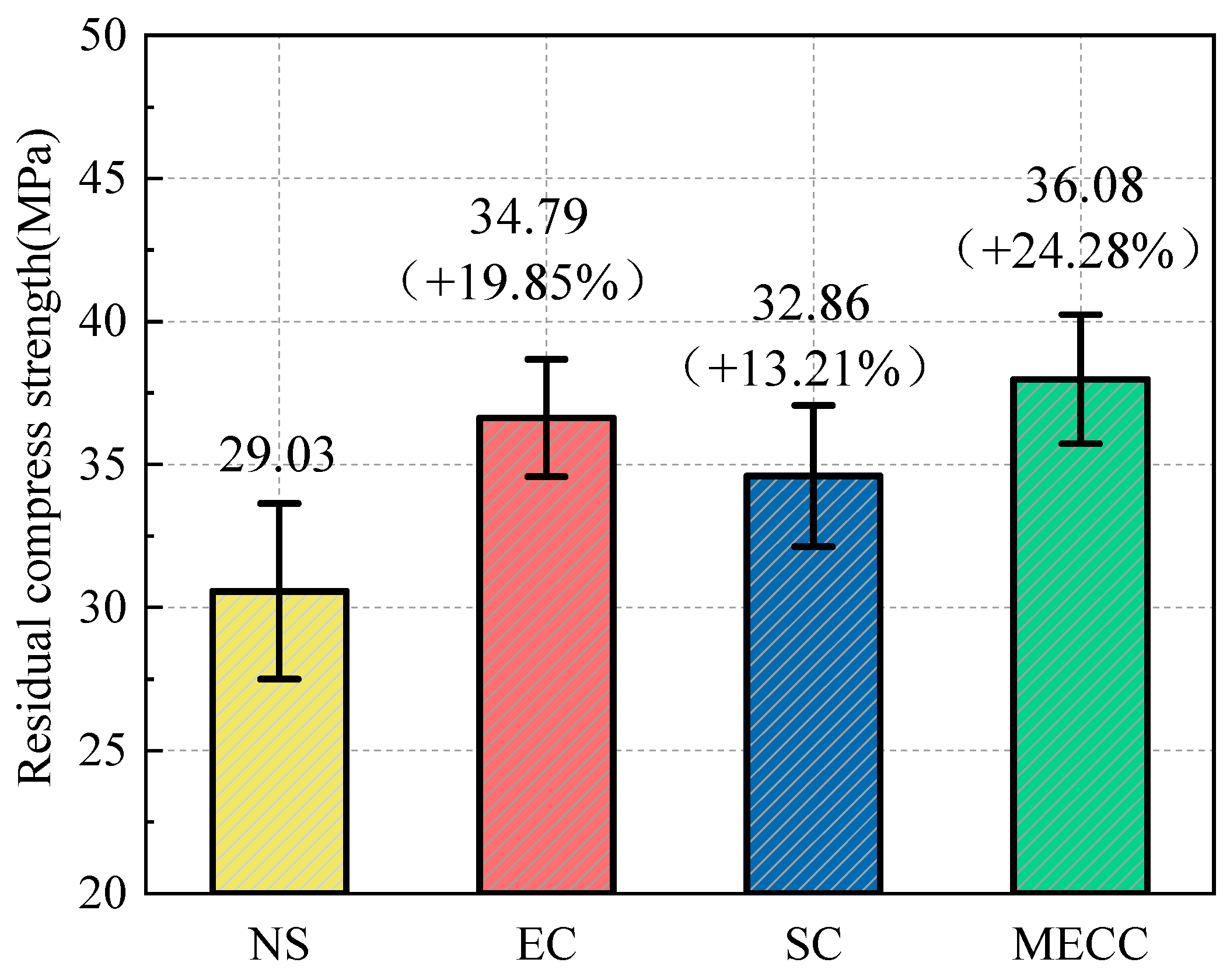

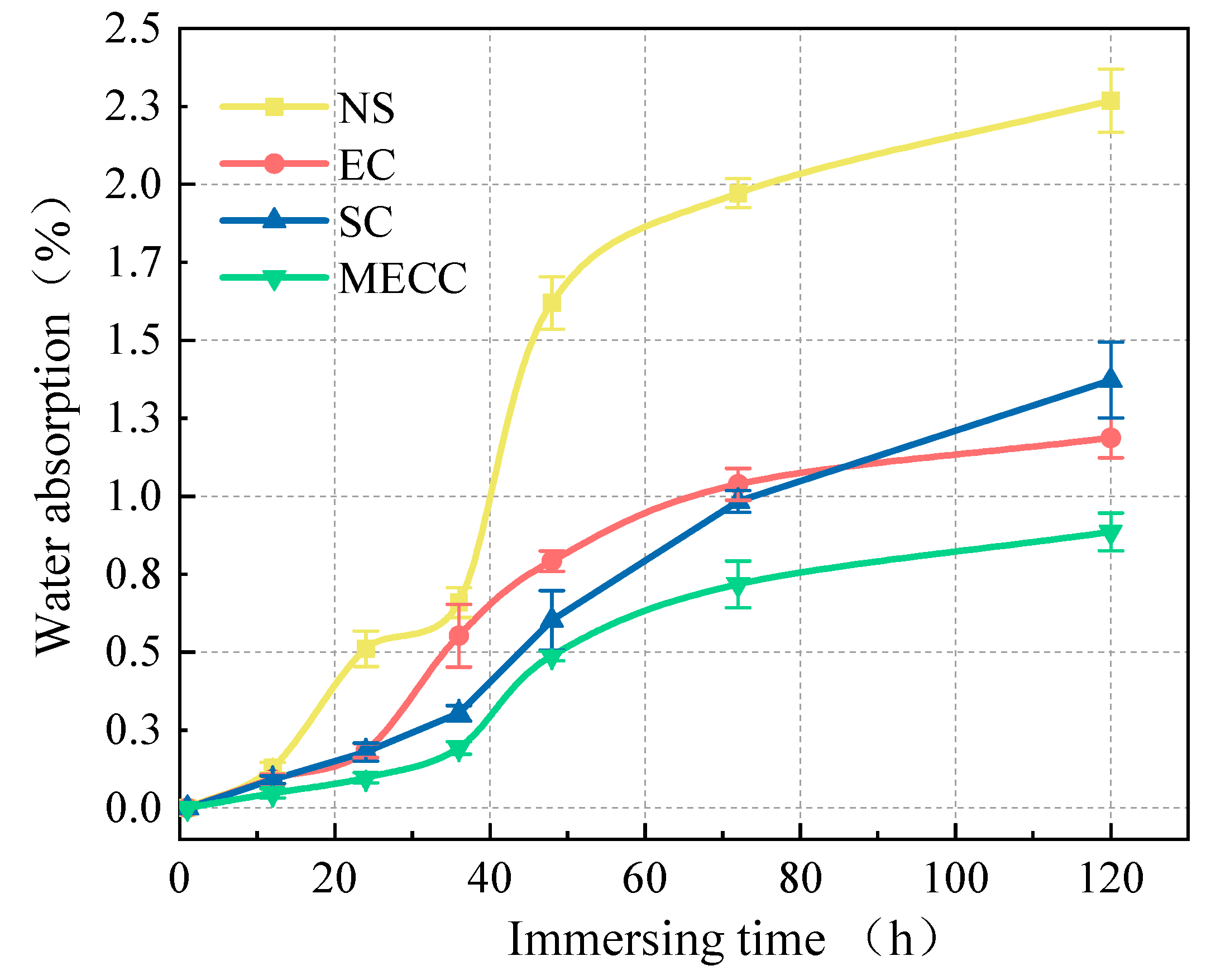

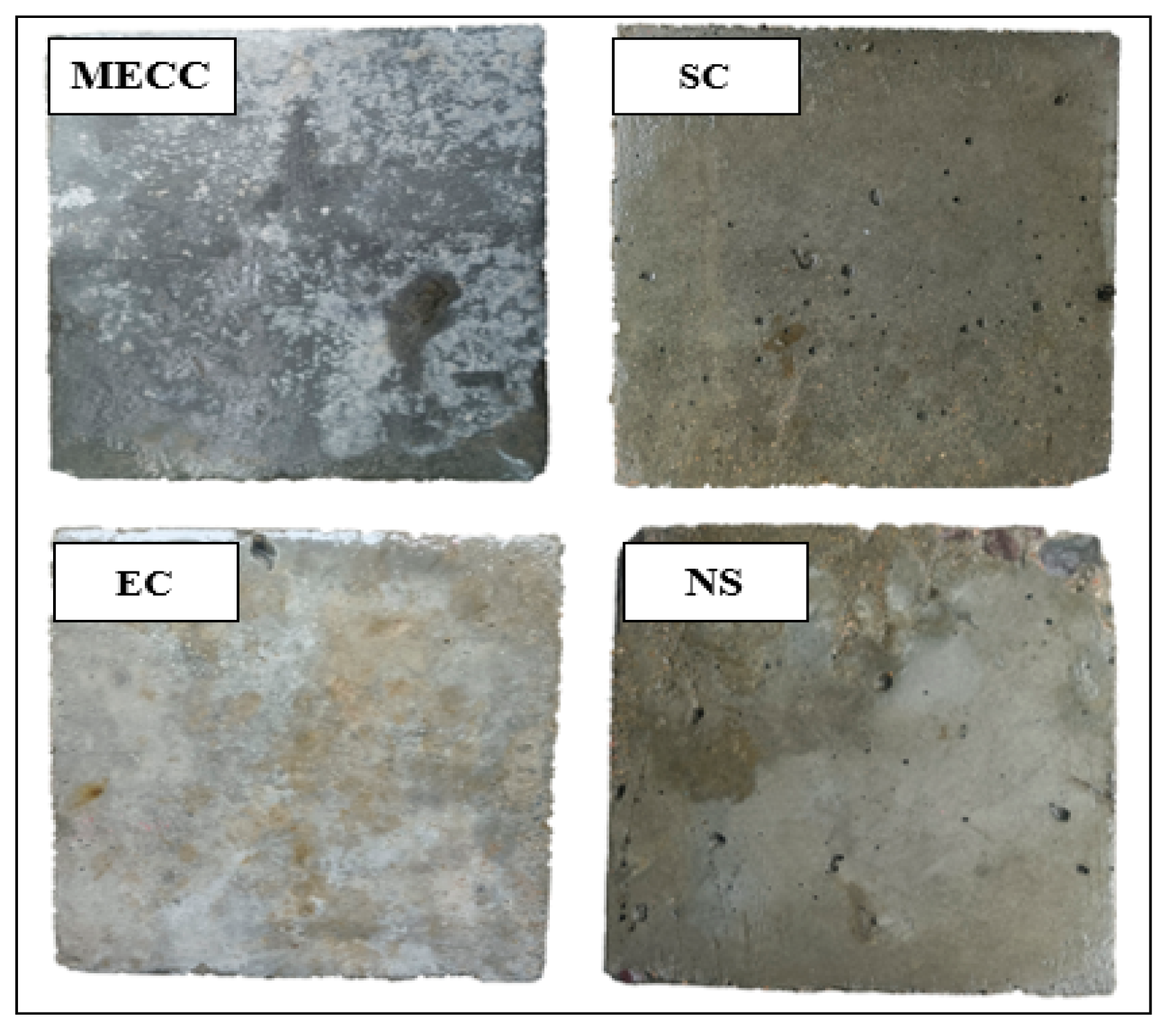

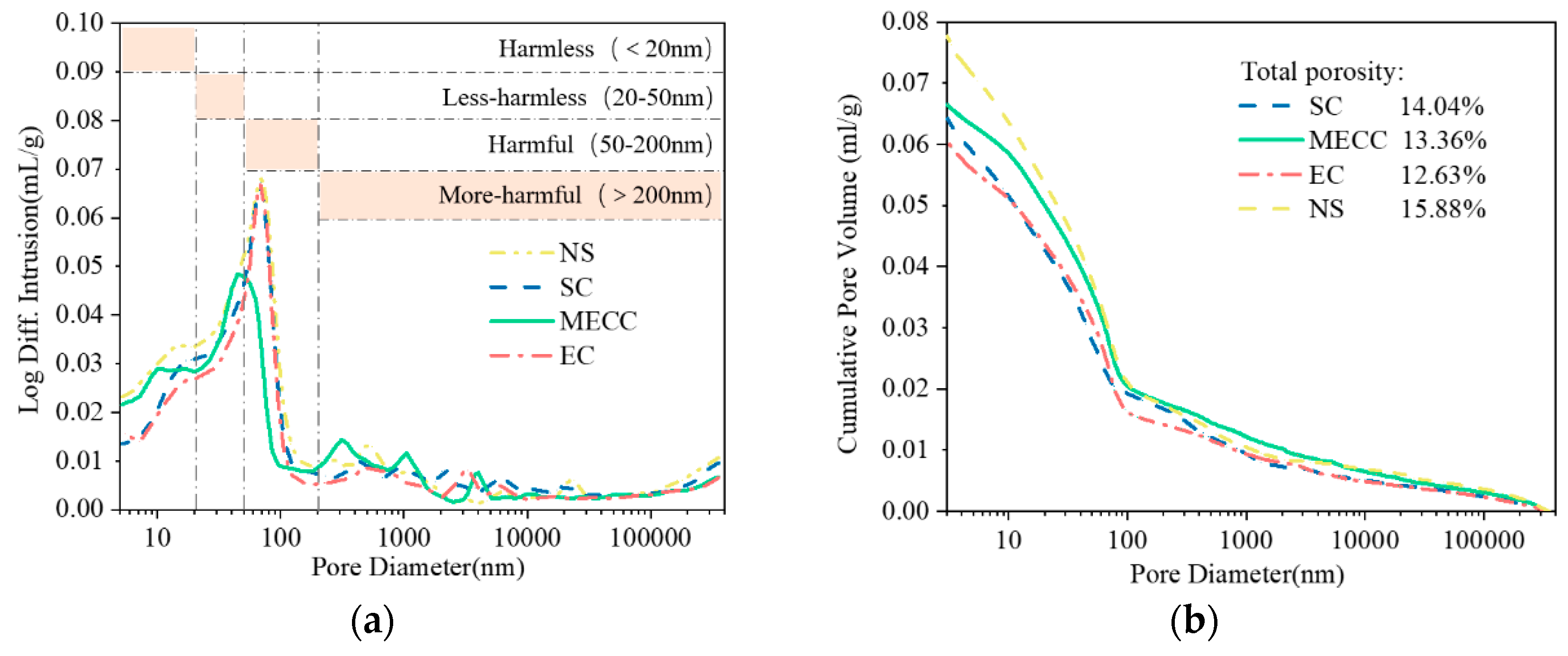

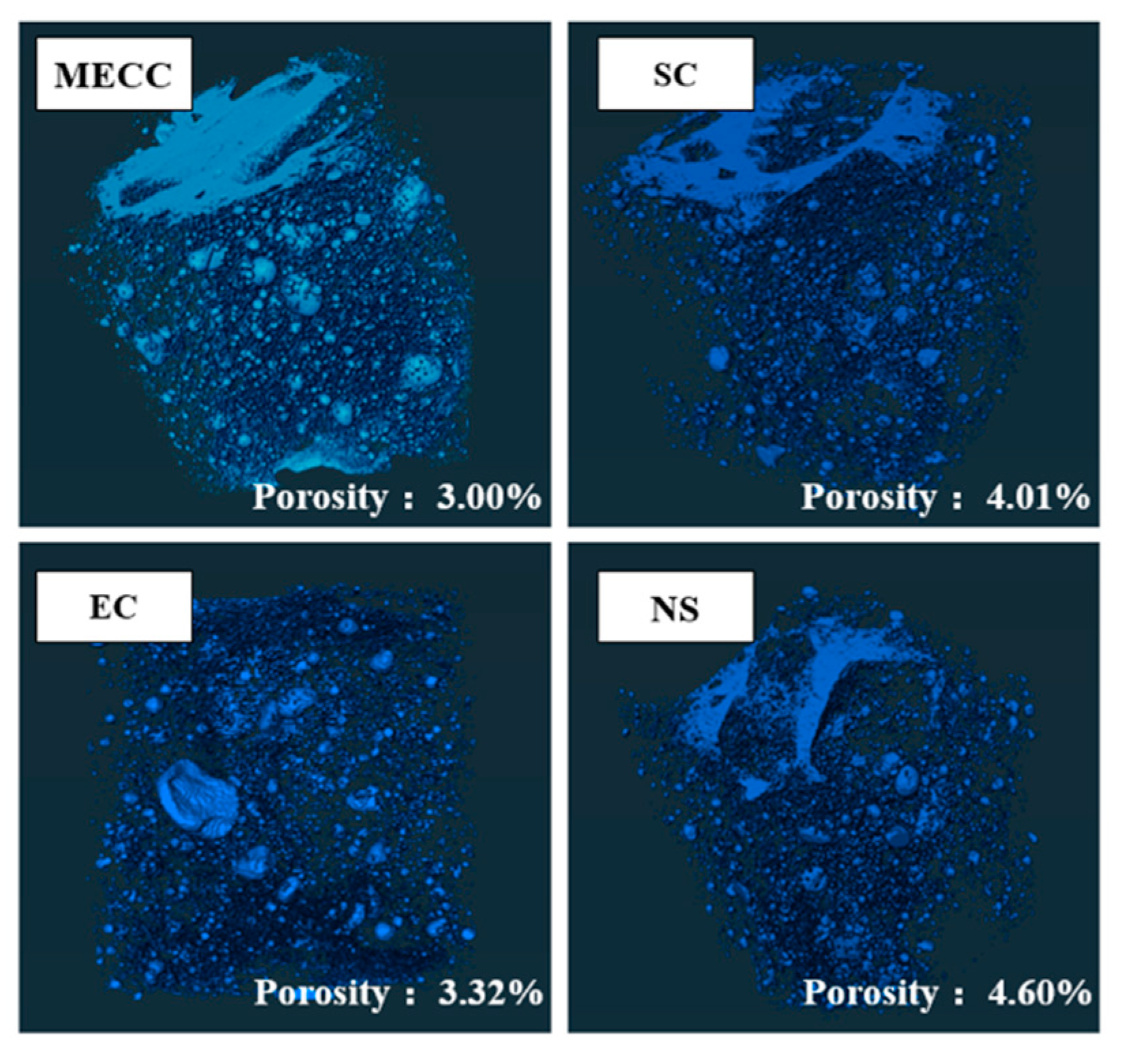

In the present study, we present a modified epoxy resin coating material and an improved epoxy resin protectant to provide longer surface protection for and enhance the durability of concrete structures on highways and bridges. Considering that dimethyl carbonate is safe and environmentally friendly and polyurethane has excellent weather and chemical resistance, high gloss, and good wear stability, we used dimethyl carbonate as the solvent and modified amines + polyaniline as a composite curing agent that reacts with epoxy resin to form a film. Through laboratory freeze-thaw tests, we determined the mass loss and relative dynamic elastic modulus (RDEM) of cement concrete specimens in 3.50 wt% NaCl and water, as well as their Chloride ion permeation resistance and saturated water absorption. We then measured the pore structure parameters of the specimens by mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) and industrial computed tomography (CT) and analyzed the mechanism underlying the salt frost durability of the MECC specimens from the micropores perspective.