1. Introduction

The rise in global beef meat demand imposes the need for a sustainable intensification of the production systems. Intensive beef production often faces challenges in optimizing both animal performance, animal welfare and health, while reducing environmental impact. It is well known that in intensive meat production systems, good rumen functioning is directly associated with animal health. Due to the type of diet used in these systems, with very high proportions of concentrate, rumen health deserves special care to guarantee high gains and conversion efficiencies [

1]. One of the most used additives for this purpose are ionophores, carboxylic polyether antibiotics naturally produced by Streptomyces spp. Particularly, monensin, ionophor produced by Streptomyces cinnamonensis, is widely used and studied [

2]. This antibiotic acts mainly reducing cell viability of Gram+ bacteria and protozoa [

3] and demonstrated to have positive effects performance and conversion in beef cattle [

4]. Regarding ruminal parameters, de Moura et al. [

5], reviewing 52 peer-reviewed publications reported that the administration of monensin does not affect NH

3-N concentration, but alters the volatile fatty acids (VFA) profile by increasing propionate and decreasing butyrate concentration. The widespread use of monensin as a growth promoter in Europe ended in January 2006, when the regulation 1831/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council (

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32003R1831) became effective. This regulation prevented the use of antibiotics used as growth promoting agents in diets, and led to the search for alternatives, mainly through plant-derived compounds and extracts [

6]. Anyway, due to the worldwide accepted action, even in Europe, monensin has continued to be used as positive control in experiments [

7].

Essential oils (EOs) are plant-derived compounds widely used instead of monensin, and according to several reports could represent a good alternative [

8,

9]. However, according to others, monensin showed clearer effects than EOs [

10]. Adding to this, there is very limited information regarding the synergy between essential oils and other phytogenic compounds, such as tannins, which could potentially enhance the effectiveness of the blend.

ANAVRIN

® (ANAVRIN

®, VetosEurope, Lugano, Swuitzerland) contains EOs, and also includes tannins and bioflavonoids, which can improve the action of the additive. The EOs are provided by cloves (Syzygium aromaticum), coriander seeds (Coriandrum sativum), and geranium (Pelargonium cucullatum). Cloves contain eugenol (4-allyl-2-methoxyphenol), known for its antimicrobial properties against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [

11]. Geranium oils provide also antibacterial, with additional antifungal [

12], and antioxidant effects [

13]. Coriander oils positively impacted on digestibility in ruminants by modulating rumen fermentation [

14] and have recognized antioxidant and reducing power activities [

15]. ANAVRIN

® also contains tannins from chestnuts (Castanea sativa) with beneficial properties on protein metabolism and anti-inflammatory action [

16,

17], and bioflavonoids derived from olives (Olea europaea), which have antioxidants, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties [

18]. Recent studies communicated that ANAVRIN

® increased productivity of dairy cows [

19] and beef calves [

20], in experiments that compared its incorporation against control diets without additives. Comparative studies are required to assess ANAVRIN’s efficacy across diverse production systems and conditions, and to evaluate its performance relative to monensin as a potential antibiotic replacement.

It is to note that monensin is not banned in several regions (e.g., North and South America). Considering that these are the regions with higher beef production in the world [

21], it would be interesting to evaluate whether the mixture of both additives have complementary effects, due to the similar actions and expectations. The mechanisms of action, however, have not been sufficiently studied for phytogenic mixtures [

22,

23], among which is the additive under study.

This study aimed to provide information on the efficacy of a blend of essential oils, tannins, and bioflavonoids compared to monensin, while also investigating any potential additive effects from their combined use. Our objective was to evaluate the effects of a specific blend of essential oils, tannins, and bioflavonoids compared to monensin and a combination of both, on the performance and rumen fermentation parameters of finishing steers consuming a total mixed ration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Feeding Management

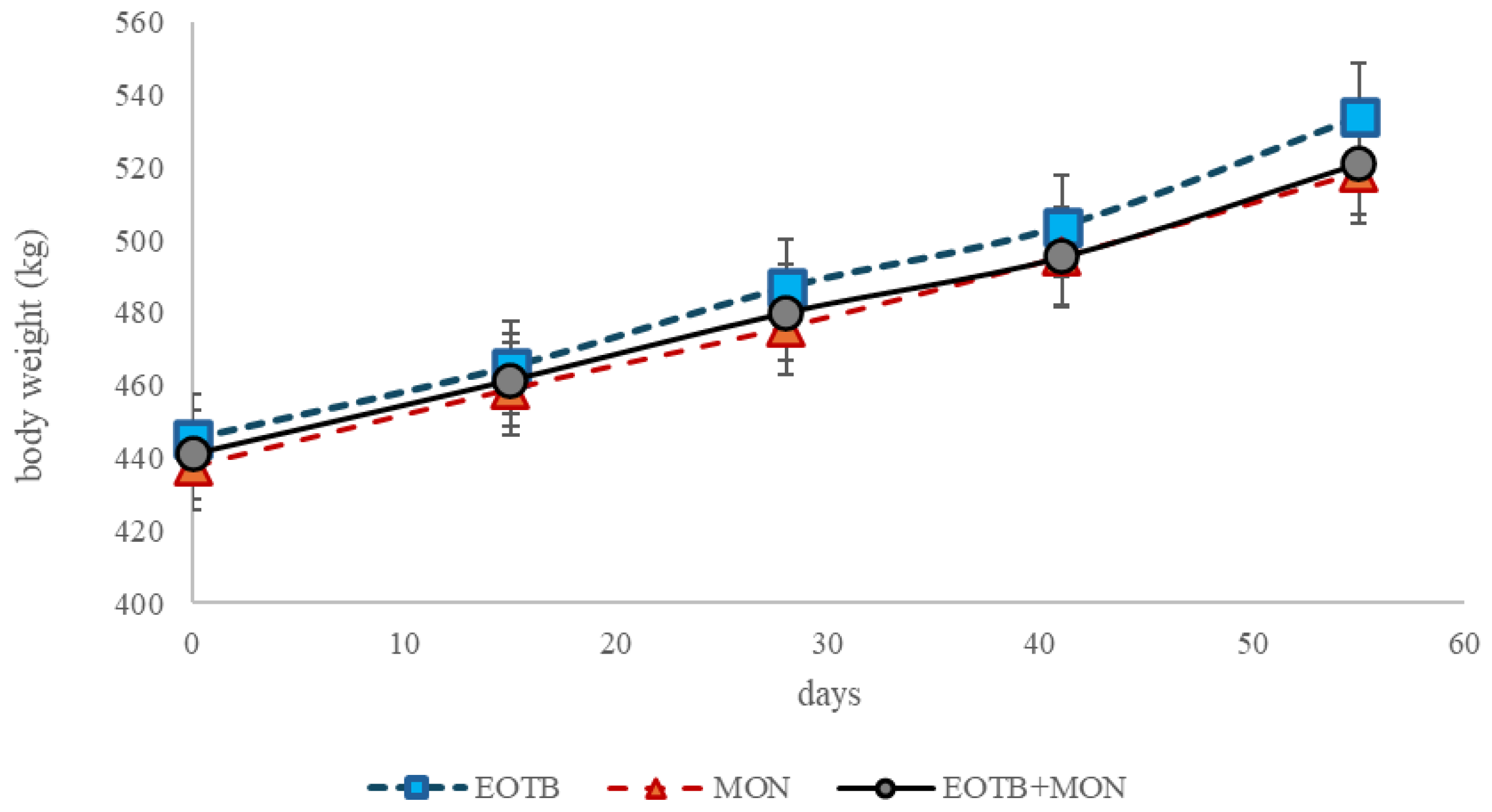

The experiment was conducted at the IPAV, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Universidad de la República (UdelaR), Uruguay (Ruta 1 km 42.5, San José, Uruguay; GPS coordinates -34.68486892825304, -56.541669330312466). Animal procedures and management adhered to the guidelines Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of the UdelaR (Protocol: 11982021). Thirty crossbred beef steers (441 ± 27 kg body weight (BW), 34.3 ± 7,1 months old) consuming a TMR were blocked by BW and randomly assigned to three dietary treatments (n=10 per treatment), which consisted in the addition to the TMR of: 1) EOTB (blend of essential oils, tannins, bioflavonoids); 2) MON (monensin) and 3) EOTB+MON.

The EOTB (ANAVRIN®), was provided at 0.35 g/100 kg body weight, monensin (Rumensin®, Elanco, Krebz, Uruguay), at 0.033 g/kg dry matter of TMR, and the combination (EOTB+MON) at the same individual dose as in 1 and 2 treatments.

Four steers per treatment had a rumen permanent catheter (8 mm diameter) inserted through the dorsal sac for rumen liquor sampling.

The TMR (

Table 1) was formulated using the Beef Cattle Nutrient Requirements Model 2016 (Version 1.0.37.15) software [

24] to achieve a target average daily gain (ADG) of 1.4 kg/day per animal. The TMR was prepared daily (08:00–10:00 h) using a vertical mixer (Mary S.R.L, Santa Catalina, Uruguay), weighed using a floor scale (EL-5 Marvic Ltd., Montevideo, Uruguay), and individually supplied for each steer. The steers were fed at 10:00 and 16:00 h, providing approximately half of the daily allowance for each meal. The TMR offered for each steer was adjusted every 12 days based on BW gain.

The experiment lasted 60 days, including a 19-day adaptation period. Three 6-day periods for data collection and sampling were included, separated by 9-day intervals. Steers were housed in individual 15 m² open-air pens with shade, feeders, and water available ad libitum.

2.2. Dry Matter Intake, Average Daily Gain, and Feed Conversion Efficiency

Individual dry matter intake (DMI) of TMR was measured over 5 consecutive days of each period, weighing the feed offered and refused. Samples of the TMR offered and refused were taken each day and frozen at -20°C for further analysis.

Steer body weights were determined by averaging two consecutive daily measurements taken at days 0-1, 14-15, 27-28, 40-41, and 54-55. All weightings were conducted before TMR feeding (08:00–10:00 h), using a bovine scale (Terko, Tk3515c, Montevideo, Uruguay). Individual daily gain (DG, kg/d) for each steer was calculated as the difference in weight (kg) divided by the number of days between weightings. Feed conversion efficiency (FCE) was calculated as the ratio of DMI to the average DG (ADG) for the whole period.

2.3. Ruminal Environment

On the first day of each measurement period, approximately 50 ml rumen fluid samples were collected via rumen catheter at eight time points (09:30, 13:00, 15:00, 17:00, 19:00, 21:00, 03:00, and 09:30 h) to determine pH, NH₃-N, and VFA concentrations. Rumen pH was measured immediately using a digital pH meter (EW-05991-36, Cole Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL, USA). A rumen fluid subsample (1 ml) was preserved with 0.02 ml of 50% (v/v) sulfuric acid and another one with 1 ml of 0.1 M perchloric acid, and frozen at -20°C for subsequent NH₃-N and VFA analysis, respectively. The NH₃-N concentrations were determined colorimetrically using a spectrophotometer (1200, UNICO

®, United Products & Instruments Inc., Dayton, OH, USA) and a phenol-hypochlorite reaction [

25]. The VFA (acetic, propionic and butyric) were analyzed by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC; Dionex Ultimate 3000, Sunnyvale, CA) according to Adams et al. [

26] using an Acclaim Rezex Organic Acid H+ (8%) column (7.8 × 300 mm) set to 210 nm. Total VFA concentration was calculated as the sum of acetic, propionic, and butyric acid concentrations.

2.4. Chemical Analysis of Feeds

Offered and refused feed samples were dried in a forced-air oven at 60°C, ground using a 1 mm sieve mill (Arthur H. Thomas Co., Philadelphia, USA), and analyzed for dry matter (DM) and ash content [

27] (Methods 942.05 and 934.01, respectively). Organic matter (OM) was calculated as the difference between DM and ash. Total N was determined using the Kjeldahl method [

27](Method 984.13), and crude protein (CP) was calculated as N × 6.25. Neutral detergent fiber (NDF) with α-amylase and sodium sulfite, acid detergent fiber (ADF) [

28] were determined, and values presented include residual ash.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.0 (SAS Institute Inc.). Outliers were identified using the PROC UNIVARIATE. The variables DMI, weight gain, and DG, data were analyzed by the PROC MIXED using the model:

Where: Yijk = dependent variable; µ = overall mean; Bi = random effect of block (i = 1 to 5); Tj = fixed effect of treatment (j = EOTB, MON, EOTB+MON); Pk = random effect of period for DMI or day of measurement for BW or DG (k = 1 to 3 or 1 to 5); Tj × Pk = fixed effect of the interaction between treatment and period; eijk = residual error. For ADG, FCE only the random effect of the block and the fixed effect of treatment were included in the model.

The variables pH, NH₃ and VFA were analyzed as repeated measures over time using the following model:

This model included, in addition to the above-mentioned effects, the fixed effects of hour of measurement (Hl = 9:30, 13:00, 15:00, 17:00, 19:00, 21:00, 03:00 h) and the interaction between treatment and hour (Tj × Hl). A spatial power (SP(POW)) for irregularly spaced data, and Tukey’s test was used for mean separation, with significance declared at P < 0.05.

3. Results

The EOTB treatment led to higher DMI compared to EOTB+MON (P=0.02) and this was the only difference on intake and performance (

Table 2,

Figure 1).

No differences were observed between treatments for average daily gain (ADG) or feed conversion rate (FCR).

Rumen fermentation variables (

Table 3) showed little variation among treatments. There were no differences for pH, NH3, and total and individual VFA expressed as percentages. However, interactions treatment × hour for total VFA, acetic and butyric acids expressed in Mm, being more stable when the combination of additives was used, respect to the other two (

Figure 2). Between treatments, the percentage of butyric acid was higher for MON respect to EOTB+MON (P=0.02), and there was a tendency for a higher propionic for EOTB+MON respect to EOTB (P=0.06). Between treatments, the percentage of butyric acid was higher for MON respect to EOTB+MON (P=0.02), and there was a tendency for a higher propionic for EOTB+MON respect to EOTB (P=0.06).

4. Discussion

It is worth noting that this study did not include control treatment without additives. While this study design does not permit isolating the impact of each additive on productive performance, it offers the innovative advantage of enabling a direct comparison of the two additives and their combined effect.

Only minor differences in voluntary intake were observed among treatments. Similarly, Diepersloot et al. [

29], working with high producing dairy cows, reported no difference in DMI after adding EOs, monensin, or a combination of both for 10 weeks. However, the additiv

e’s effect on intake varied by week. According to Wood et al. [

30], the intake reduction triggered by monensin is to be dose dependent. These authors studied the effect of increasing the dose of monensin in crossbreed finishing heifers, and observed a linear decrease of DMI as the dose increased from 0 to 48 mg monensin/kg of TMR. The highest dose employed by those authors was equivalent to 60 mg/kg DM, while in our study, monensin was provided at 33 mg/kg DM. Although the effect of monensin in reducing DMI is well-documented [

30,

31], there is less information available regarding the impact of EOs blends. In a recent study by Silvestre et al. [

32], working with dairy cow, did not find effect on DMI after adding EOs from geranium and cloves to the diet, and Atzori et al. [

33] didn’t find differences between a control diet, and the same diet supplemented with the blend of EOs, tannins and bioflavonoids used in this article, in dairy sheep. This aligns with the findings of the metanalyses of Belanche et al. [

9], who indicated that the essential oil blend had no impact on DMI or milk composition. The only difference observed in the present study was a higher DMI in EOTB treatment compared to EOTB+MON, which suggests that the studied blend counteracted the intake-reducing effect of monensin. In our study, the inclusion of tannins does not appear to have negatively affected intake, as reported in the literature [

34].

The higher intake in EOTB did not affect ADG or FCR, which showed no differences between treatments. Although the absolute values could suggest a higher ADG with EOTB treatments, the absence of differences indicates that more animals would be needed to confirm this assumption.

Rumen pH values observed in this study were comparable to those reported for similar diets and remained above the levels deemed at risk [

35]. The similarity of rumen pH among treatments is consistent with the absence of differences in VFA concentrations. Neither Diepersloot et al. [

29] nor Flores et al. [

36] observed major differences in pH or VFA concentrations. The only notable finding reported by the latter was an increase in butyrate concentration. It is noteworthy that although tannins are generally recognized as VFA concentration reducers [

37], in the EOTB treatment VFA were not reduced. This can be due because of the type of tannins contained in this specific blend (from chestnut). Buccioni et al. [

38], studying the effect of adding chestnut or quebracho tannins to dairy sheep diets, reported that tannins from quebracho reduced VFA concentrations, but tannins form chestnuts increased their concentration respect to the control. Among VFA, the higher butyric percentage observed with monensin can be related with the fact that Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens, a butyric acid-producing Gram-positive bacteria, is insensitive to dietary ionophores [

3].

The interaction observed in VFA kinetics along time, with a more stable VFA concentration for EOTB+MON is an interesting finding. Although there is a slight effect, this can evidence a possible complementary action between monensin and this EOTB blend, which should be confirmed by deeper studies in rumen environment and microbiota. It is known that EOs, tanins and bioflavonoids can modify rumen microbiota [

6,

39,

40]. However, the diversity of components and their specific actions make it difficult to identify the precise mechanisms at work in this situation.

The lack of differences in ruminal ammonia concentrations was expected. Monensin is known to inhibit amino acid-fermenting bacteria [

41]. The blend of EOTB, on the other hand, contains tannins, which are known to reduce protein degradation by forming insoluble complexes with proteins [

42]. Therefore, although through different mechanisms, both additives tend to reduce ruminal ammonia concentrations. The different mechanisms of both additives suggest potential complementarity, leading to the expectation that the EOTB+MON treatment would result in lower ammonium concentrations, which was not observed.

5. Conclusions

The addition of a blend of essential oils, tannins, bioflavonoids to finishing steers fed total mixed ration resulted in similar performance outcomes to monensin. However, the more stable volatile fatty acids concentration along time with the treatment that combined both additives, can support a possible complementary action, which should be confirmed by microbiome profile studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.R. and C.C.; methodology, J.L.R, E.C., A.S and C.C.; software, E.C. and A.S.; validation, J.L.R., E.C., A.S., G.C. and C.C.; formal analysis, E.C. and A.S.; investigation, E.C. and G.C.; resources, J.L.R. and C.C.; data curation, E.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.R. and C.C.; writing—review and editing, J.L.R., E.C., A.S., G.C. and C.C. ; visualization, E.C. and C.C.; supervision, J.L.R. and A.S.; project administration, C.C.; funding acquisition, C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Campo Express S.A. under research agreement between Campo Express S.A. and Marco Podestá Foundation, FVet, UdelaR and the APC was funded by VetosEurope.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of the UdelaR (Protocol: 11982021).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to research agreement restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the Experimental Station of the Veterinary Faculty for providing facilities, C. Casini and A. Bentancur for administrative support, and J. Dayuto for assistance with animal care.

Conflicts of Interest

The experimental design of this study was discussed and agreed with Campo Express S.A. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

ADF Acid Detergent Fiber

ADG Average Daily Gain

BW Body Weight

CP Crude Protein

CG Ground Corn Grain

DM Dry Matter

DMI Dry Matter Intake

EOTB Essential Oil Tannin Blend

EOTB+MON Combination of EOTB and MON

FCR Feed Conversion Ratio

HPLC High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

MON Monensin

References

- Brown, M.S.; Ponce, C.H.; Pulikanti, R. Adaptation of beef cattle to high-concentrate diets: Performance and ruminal metabolism1. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 84, E25–E33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffield, T.; Rabiee, A.; Lean, I. A Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Monensin in Lactating Dairy Cattle. Part 1. Metabolic Effects. J. Dairy Sci. 2008, 91, 1334–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, R.d.S.; Cooke, R.F. Effects of Ionophores on Ruminal Function of Beef Cattle. Animals 2021, 11, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffield, T.F.; Merrill, J.K.; Bagg, R.N. Meta-analysis of the effects of monensin in beef cattle on feed efficiency, body weight gain, and dry matter intake1. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 4583–4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moura, D.C.; Torres, R.d.N.S.; da Silva, H.M.; Donadia, A.B.; Menegazzo, L.; Xavier, M.L.M.; Alessi, K.C.; Soares, S.R.; Ghedini, C.P.; de Oliveira, A.S. Meta-analysis of the effects of ionophores supplementation on dairy cows performance and ruminal fermentation. Livest. Sci. 2021, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calsamiglia, S.; Busquet, M.; Cardozo, P.; Castillejos, L.; Ferret, A. Invited Review: Essential Oils as Modifiers of Rumen Microbial Fermentation. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 2580–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devant, M.; Anglada, A.; Bach, A. Effects of plant extract supplementation on rumen fermentation and metabolism in young Holstein bulls consuming high levels of concentrate. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2007, 137, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, N.F.; Erickson, G.E.; Klopfenstein, T.J.; Greenquist, M.A.; Luebbe, M.K.; Williams, P.; Engstrom, M.A. Effect of essential oils, tylosin, and monensin on finishing steer performance, carcass characteristics, liver abscesses, ruminal fermentation, and digestibility1. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87, 2346–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belanche, A.; Newbold, C.J.; Morgavi, D.P.; Bach, A.; Zweifel, B.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R. A Meta-analysis Describing the Effects of the Essential oils Blend Agolin Ruminant on Performance, Rumen Fermentation and Methane Emissions in Dairy Cows. Animals 2020, 10, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drong, C.; Meyer, U.; Von Soosten, D.; Frahm, J.; Rehage, J.; Breves, G.; Dänicke, S. Effect of monensin and essential oils on performance and energy metabolism of transition dairy cows. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2016, 100, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorman, H.J.D.; Deans, S.G. Antimicrobial agents from plants: antibacterial activity of plant volatile oils. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 88, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman, S.; Voaides, C.; Babeanu, N. Exploring the Sustainable Exploitation of Bioactive Compounds in Pelargonium sp.: Beyond a Fragrant Plant. Plants 2023, 12, 4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehme, R.; Andrés, S.; Pereira, R.B.; Ben Jemaa, M.; Bouhallab, S.; Ceciliani, F.; López, S.; Rahali, F.Z; Ksouri, R.; Pereira, D.M.; et al. Essential Oils in Livestock: From Health to Food Quality. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matloup, O.; El Tawab, A.A.; Hassan, A.; Hadhoud, F.; Khattab, M.; Sallam, S.; Kholif, A. Performance of lactating Friesian cows fed a diet supplemented with coriander oil: Feed intake, nutrient digestibility, ruminal fermentation, blood chemistry, and milk production. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2017, 226, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahwar, M.K.; El-Ghorab, A.H.; Anjum, F.M.; Butt, M.S.; Hussain, S.; Nadeem, M. Characterization of Coriander (Coriandrum sativumL.) Seeds and Leaves: Volatile and Non Volatile Extracts. Int. J. Food Prop. 2012, 15, 736–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanat, F.; Benchaar, C. Assessment of the effect of condensed (acacia and quebracho) and hydrolysable (chestnut and valonea) tannins on rumen fermentation and methane production in vitro. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 93, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboagye, I.A.; Beauchemin, K.A. Potential of Molecular Weight and Structure of Tannins to Reduce Methane Emissions from Ruminants: A Review. Animals 2019, 9, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olagaray, K.; Bradford, B. Plant flavonoids to improve productivity of ruminants – A review. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2019, 251, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, C.A.S.; Grossi, S.; Dell’anno, M.; Compiani, R.; Rossi, L. Effect of a Blend of Essential Oils, Bioflavonoids and Tannins on In Vitro Methane Production and In Vivo Production Efficiency in Dairy Cows. Animals 2022, 12, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossi, S.; Compiani, R.; Rossi, C.A.S. Effect of the Administration of a Blend of Essential Oils, Bioflavonoids, and Tannins to Veal Calves on Growth Performance, Health Status and Methane Emissions. Large Anim. Rev. 2024, 30, 163–169. [Google Scholar]

-

World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2023; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2023.

- Mendel, M.; Chłopecka, M.; Dziekan, N.; Karlik, W. Phytogenic feed additives as potential gut contractility modifiers—A review. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2017, 230, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastoh, N.A.; Waqas, M.; Çınar, A.A.; Salman, M. The impact of phytogenic feed additives on ruminant production: A review. J. Anim. Feed. Sci. 2024, 33, 431–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 30. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle: Eight Revised Edition; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherburn, M.W. Phenol-hypochlorite reaction for determination of ammonia. Anal. Chem. 1967, 39, 971–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Jones, R.; Conway, P. High-performance liquid chromatography of microbial acid metabolites. J. Chromatogr. B: Biomed. Sci. Appl. 1984, 336, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of the AOAC. In International.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists International: Washington, DC, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diepersloot, E.C.; Pupo, M.R.; Heinzen, C.; Souza, M.S.; Ferraretto, L.F. Effect of monensin and essential oil blend supplementation on lactation performance and feeding behavior by dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, K.M.; Pinto, A.C.J.; Millen, D.D.; Guzman, R.K.; Penner, G.B. The effect of monensin concentration on dry matter intake, ruminal fermentation, short-chain fatty acid absorption, total tract digestibility, and total gastrointestinal barrier function in beef heifers1. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 2471–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- e Silva, S.; Chabrillat, T.; Kerros, S.; Guillaume, S.; Gandra, J.; de Carvalho, G.; da Silva, F.; Mesquita, L.; Gordiano, L.; Camargo, G.; et al. Effects of plant extract supplementations or monensin on nutrient intake, digestibility, ruminal fermentation and metabolism in dairy cows. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2021, 275, 114886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, T.; Martins, L.; Cueva, S.; Wasson, D.; Stepanchenko, N.; Räisänen, S.; Sommai, S.; Hile, M.; Hristov, A. Lactational performance, rumen fermentation, nutrient use efficiency, enteric methane emissions, and manure greenhouse gas-emitting potential in dairy cows fed a blend of essential oils. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 7661–7674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atzori, A.S.; Porcu, M.A.; Fulghesu, F.; Ledda, A.; Correddu, F. Evaluation of a dietary blend of essential oils and polyphenols on methane emission by ewes. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2023, 63, 1483–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frutos, P.; Hervás, G.; Giráldez, F.J.; Mantecón, A.R. Review. Tannins and ruminant nutrition. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2004, 2, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraja, T.G.; Titgemeyer, E.C. Ruminal acidosis in beef cattle: The current microbiological and nutritional outlook. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, E17–E38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, A.J.; Garciarena, A.D.; Vieyra, J.M.H.; Beauchemin, K.A.; Colombatto, D. Effects of specific essential oil compounds on the ruminal environment, milk production and milk composition of lactating dairy cows at pasture. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2013, 186, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasta, V.; Daghio, M.; Cappucci, A.; Buccioni, A.; Serra, A.; Viti, C.; Mele, M. Invited review: Plant polyphenols and rumen microbiota responsible for fatty acid biohydrogenation, fiber digestion, and methane emission: Experimental evidence and methodological approaches. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 3781–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccioni, A.; Pauselli, M.; Viti, C.; Minieri, S.; Pallara, G.; Roscini, V.; Rapaccini, S.; Marinucci, M.; Lupi, P.; Conte, G.; et al. Milk fatty acid composition, rumen microbial population, and animal performances in response to diets rich in linoleic acid supplemented with chestnut or quebracho tannins in dairy ewes. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 1145–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, B.; Barry, T.; Attwood, G.; McNabb, W. The effect of condensed tannins on the nutrition and health of ruminants fed fresh temperate forages: a review. 106, 19. [CrossRef]

- Asif, M. Bioactive Phytochemical Constituents of Some Edible Fruits of Myrtaceae Family. 2015. American Journal of Nutrition Research 1:1–17.

- Yang, C.M.; Russell, J.B. The effect of monensin supplementation on ruminal ammonia accumulation in vivo and the numbers of amino acid-fermenting bacteria. J. Anim. Sci. 1993, 71, 3470–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhao, G.; Hu, T.; Wang, Y. Potential and challenges of tannins as an alternative to in-feed antibiotics for farm animal production. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 4, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).