1. Introduction

The standard model of cosmology, rooted in the Big Bang paradigm and the theory of General Relativity (GR), has been remarkably successful in explaining key observations, such as the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), the large-scale structure of the Universe, and the accelerating cosmic expansion attributed to dark energy. However, several fundamental questions remain unresolved, such as the nature of the initial singularity, the flatness and horizon problems, and the physical origin of dark energy. These challenges have spurred the development of alternative frameworks that seek to extend or complement the standard cosmological model.

One such alternative is the Black Hole Universe (BHU) model, which posits that our observable Universe resides within a black hole. This model provides a fresh perspective on spacetime evolution, linking black hole dynamics to large-scale cosmic phenomena. The BHU model interprets the observed cosmological constant () as an effective boundary term arising from the black hole’s horizon, bypassing the need to invoke a fundamental term or any exotic dark energy component.

In this Letter, we explore the collapse of a spherically symmetric matter cloud as a precursor to the expansion of the Universe within the BHU framework. We propose that quantum effects above nuclear saturation densities drive a gravitational bounce, which then initiates an inflationary phase analogous to cosmic inflation. Crucially, this quantum mechanism violates the strong energy condition (SEC) in classical GR. As was shown in Pradhan et al. (2025), the bounce requires a non-zero local curvature . Both conditions sidestep the singularity GR theorems proposed by Hawking et al. (1970), allowing us to formulate a novel solution to a pivotal issue in cosmological theory. The bounce naturally resolves the horizon and flatness problems while eliminating the need for a separate inflationary mechanism. Unlike standard inflation, the BHU model introduces a finite cutoff for super-horizon perturbations, potentially explaining anomalies in the CMB, such as the absence of structures beyond 66 degrees (Gaztañaga and Camacho-Quevedo 2022).

Pradhan et al. (2025) have numerically solved the Newtonian spherical collapse equations with a polytropic equation of state (EoS) inspired by neutron star conditions. They investigated bounces at or above nuclear saturation density with equivalent GR behaviour in a closed FLRW metric. The GR bounce corresponds to the ground state of the matter, characterized by . Here, we elaborate on the underlying mechanisms of this phenomenon and its implications for cosmic evolution.

Our framework relates to other cosmological bouncing scenarios (such as Starobinskii 1978; Starobinsky 1980; Brandenberger and Peter 2017; Nojiri et al. 2017; Odintsov et al. 2020; Kiefer and Mohaddes 2024) with some critical distinctions. Unlike other approaches, which modify gravity or try to quantize matter to explain the bounce, we employ an effective scalar field analogous to that in standard cosmic inflation models within standard GR. Moreover, we incorporate spatial curvature, demonstrating its essential role in enabling the bounce. Finally, we address how cosmic acceleration emerges as a natural consequence of the bounce.

This work extends the BHU model (Gaztañaga 2022; Gaztañaga 2023) to a closed FLRW cloud . The flat case used previously is a good approximation all the way to the point where we approach the singularity but does not allow for a bounce to occur. By connecting the early and late phases of cosmic evolution, we provide a unified model that bridges gravitational collapse, cosmic inflation, and the present accelerated expansion of the Universe. Grounded in physical principles and supported by numerical simulations, this model offers a compelling alternative to the standard cosmological paradigm while addressing its unresolved challenges.

2. Spherical Collapse

Here, we want to model the collapse of a finite cloud or perturbation within a larger background. We will assume that the initial cloud is a spherical overdense region of a perfect fluid that is surrounded by an empty space, as shown in

Figure 1 of Pradhan et al. (2025). This configuration is embedded in a larger volume containing a homogeneous, more diluted fluid. We also assume that

or negligible to start with. For an observer moving with a perfect fluid, the energy-momentum tensor is diagonal:

, where

is the relativistic energy density and

is the pressure. The cloud is initially very large and has a very low density, so the pressure and temperature can be neglected. The relativistic solution to this problem was given by Lemaitre (1933) ‘atom universe’ and is known today as the Lemaitre-Tolman-Bondi (LTB) model. In Lemaitre (1933) original paper (i.e. Eq.8.1), the metric for such cloud was written as:

where

with

. The physical radius

corresponds to the area distance. The general solution to the Einstein field equation is:

where the over dots correspond to partial time derivatives. The mass-energy

M was introduced by Lemaitre (1933) and is sometimes called the active gravitational mass or the relativistic Misner-Sharp mass (Misner and Sharp 1964).

Assuming a homogeneous cloud

requires

H to also be homogeneous. Consequently,

and

k has to be constant. We then have:

where

and

are the initial density and comoving radius of the cloud so that the mass

m inside

remains constant. Note that we use comoving units such that

at present. This is the same solution as the FLRW solution, as expected. In general, we can choose

k to have any sign depending on the initial conditions. The case of interest here is

, which corresponds to an overdensity. This reproduces the well-known result that a closed FLRW model exactly reproduces the relativistic spherical collapse model (see §87 in Peebles 1980). The metric of our initial perturbation for

is therefore the same as the one of a closed FLRW metric:

Note that because we are assuming that

is cosmologically large, the corresponding curvature term

is small throughout the evolution until we approach the singularity at

. The solutions in Eqs.

4-5, and also for Eqs.

2-3, with

are the same as those in the Newtonian collapse studied in Pradhan et al. (2025) (note that the corresponding Newtonian energy

). The FLRW cloud is a local and finite LTB solution in contrast to the standard FLRW metric, which is global and infinite.

What happens in the LTB solution for in the region of empty space surrounding R? Lemaitre (1933) also found a solution to this question. In his §11, he shows how variables can be changed to transform the LTB solution into the static Schwarzschild metric. This change of variables corresponds to a frame that is not comoving with the fluid, just as in the case of the static version of the de-Sitter metric (i.e., see Gaztañaga 2024). Another way to approach this question is to show that the FLRW metric matches with the Schwarzschild metric without discontinuities (see e.g., Stuckey 1994 and 12.5.1 in Padmanabhan 2010). This solution is what we call the FLRW cloud, which has the FLRW metric inside and the Schwarzschild metric outside (Gaztañaga 2022).

As the FLRW cloud collapses under its own gravity (

), the outer physical radius

shrinks and eventually crosses inside the corresponding Schwarzschild radius:

. When this happens, the FLRW cloud becomes a BH. Both

and

are cosmologically very large, which means that the corresponding densities are very small. The density at a given time

before the collapse to the singularity in the absence of any pressure is

If we take

m to be as large as the mass of our observable Universe (

), we find from Eq.5 that at horizon crossing:

the density of the BH,

is:

At these low densities, it is reasonable to assume that the thermal pressure

P and temperature

T are negligible because the time scale of the collapse is negligible compared to the time scales for any interactions between neutral particles. The cold collapse proceeds inside the BH event horizon as if no BH were formed. Note in Eq.

7 how even up to one second before the singularity occurs, the density is small compared to nuclear saturation in a Neutron Star (NS):

3. Degeneracy Pressure

As the collapsing cloud approaches the singularity (), the density increases without bound. However, once any fermionic constituent of the cloud reaches its quantum ground state, the Pauli Exclusion Principle generates a degeneracy pressure, , independent of temperature. Remarkably, this degeneracy pressure and the corresponding equilibrium density apply universally to systems ranging from atoms to neutron stars (NS) despite their vast difference in mass—approximately times. For even larger masses, such as the mass of the Universe (about times greater than that of a neutron star), the degeneracy pressures of electrons, neutrons, or even quarks may not suffice to halt the collapse. Indeed, for masses exceeding the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff (TOV) limit of 2–3 , a black hole forms, and the collapse proceeds within the event horizon, leaving the internal physics largely unexplored. The Pauli Exclusion Principle should remain valid even under extreme conditions, as no two fermions can occupy the same quantum state. Thus, a new quantum ground state, characterized by a maximum density , could also emerge if electrons and quarks are not fundamental, preventing a true singularity. This notion lies at the heart of quantum mechanics, offering a framework to circumvent singular collapse and explore the limits of physical laws in extreme conditions.

In the central regions of the collapsing cloud, where the bounce occurs, the pressure and density can be treated as approximately uniform. The validity of this assumption was demonstrated in Pradhan et al. (2025). The FLRW cloud solution with

changes to:

where we have set

for clarity. Even if

is non-zero, its contribution can be neglected when we approach nuclear densities. We shall model the quantum ground state of nuclear saturation by introducing a scalar degree of freedom

. Consider the Einstein-Hilbert action with minimally coupled matter fields with Lagrangian

:

where the last integral represents the Gibbons-Hawking-York (GHY) boundary term (York 1972; Gibbons and Hawking 1977; Hawking and Horowitz 1996), and

is the trace of the extrinsic curvature at the boundary

. This term is needed in the cases where the manifold under study

has some boundary

(as happens inside a BH). The energy-momentum

is defined as:

The least action principle with respect to the metric

yields Einstein field equations:

where variations of the field are zero at the integration limits thanks to the GHY boundary term. For the Lagrangian, we consider a combination of a perfect fluid and an effective minimally coupled scalar field

with:

, where

and

is the standard matter-energy content. We have defined

and

is the potential of the classical scalar field

. We will next explore the regime where

is dominated by

. If both

and

contributions are not coupled, then the general result would correspond to just adding both contributions to

P and

. We can estimate the contribution of the scalar field

from equation (

13):

Choosing an observer that is moving with the fluid and comparing it to a perfect fluid, we can identify (see also equations B66-B68 in Weinberg 2008):

where we have defined

. The ground state

of the system corresponds to the configuration in which the energy is minimized. In a relativistic context, this often means that the kinetic contributions (derived from the gradient terms

) become insignificant compared to the potential energy

. This simply means that the total energy is dominated by the potential energy. We expect something similar to happen when the collapsing cloud reaches the ground state at some supra-nuclear densities in a cold collapse. The dynamics will be dominated by the potential of the interaction of quantum particles, and their kinetic energy will not play a significant role in the evolution at the bounce. Close to the ground state,

. During its evolution, first, the cloud ascends (rolls up) towards the potential

as it collapses, and after the bounce, it descends (rolls down). Analogously to the scalar field considered here, a fluid with a given EoS will reach some saturation density

. Consequently, the EoS plays the role of the scalar potential. While the pressure is still small, the corresponding cloud radius

can be obtained from Eq.5:

For the mass of the Universe

and when assuming nuclear saturation density as a lower limit

(Eq.

9):

This value of represents the beginning of the transition into the ground state. The model transitions from constant energy-mass to constant energy-density.

We have found that the quantum exclusion principle leads to a ground state where the relativistic equation of state (EoS) becomes: . This EoS is fundamentally distinct from the one typically considered under nuclear saturation in neutron stars (NS). A key assumption in standard models is that general relativity (GR) is negligible at scales of inter-quantum interactions. However, it is crucial to recognize that gravity is inherently nonlinear. The active mass-energy, as defined in Eq.3, includes not only matter but also gravitational energy. Notably, around the ground state, the active mass exhibits exponential growth or decay in the comoving frame, highlighting a purely gravitational effect. This behavior is also captured in the relativistic continuity equation (Eq.11): . Here, the term reflects a uniquely relativistic contribution, which is not present in newtonian physics. This equation demonstrates that, upon reaching a constant density, the EoS naturally transitions to (back in units of ). This behavior is not captured by conventional EoS models for NS, emphasizing the necessity of considering relativistic effects in describing such ground states.

4. Bouncing Solution

Bringing together the insights from the two previous sections, we can now explore what happens during the collapse of an FLRW cloud as it reaches its ground state density somewhere above nuclear saturation. For a constant

, Eq.

10- become:

This corresponds to a gravitational bounce (

and

) at:

Note how it is critical that

(or

) to have a bounce before the singularity (

) occurs. The bounce is only possible because both

and the cloud is finite (that is,

and

). An infinite FLRW cloud has no bounce. The existence of

imposes a natural cutoff in the spectrum of super-horizon perturbations generated during collapse, bounce, or inflation. It should show up in the CMB sky as:

where

Gpc is the comoving radial distance to the CMB for

and

km/s/Mpc. Strong evidence for such a cutoff has been known since COBE and confirmed by WMAP and Planck (Hinshaw and et al 1996; Spergel et al. 2003; Planck Collaboration et al. 2020). Camacho-Quevedo and Gaztañaga (2022) estimated the homogeneity scale to be:

which implies:

If we use as a reference

Gpc in Eq.

18 we get:

from Eq.

21. The exact solution to Eq.20 is:

where

is the time to/from the bounce (

) with

, and

is the radius of the cloud when it bounces:

which happens to be the gravitational radius of the ground state

.

5. Cosmic Inflation and Nucleosynthesis

The solution in Eq.

25 corresponds to an exponential expansion (or collapse) after (or before) the bounce, leading to a de-Sitter phase, just as in standard cosmic inflation. As mentioned before, the EoS plays the role of the inflation potential, and the actual solution is quasi-de-Sitter as we approach the respective ground state of the matter. For example, for

, we have

km, which is much smaller than the radius of the cloud when it approaches its ground state,

. The logarithmic ratio of these two radii:

gives the number of e-folds between the bounce and the ground state. For

, there are 17 e-folds, but the actual number should be larger if the ground state occurs at higher densities, as found in the model of Pradhan et al. (2025). The lower the density at which degeneracy pressure occurs, the more e-folds of expansion (slow-roll) are required to reduce the density again to (

), moving away from the ground state and ending inflation. In a more realistic situation, the bounce will not be cold. This not only means that there are photons present that mediate thermal pressure but also that there could be nuclear reactions occurring simultaneously. This opens the possibility for an epoch of nucleosynthesis and recombination similar to that in the standard model (e.g. see Steigman 2007).

As mentioned before, the saturation densities in neutron stars and the nucleus of an atom are comparable with Eq.

9 despite the former having a mass

times larger than the latter. However, as discussed in Pradhan et al. (2025), the densities at which the condition

is fulfilled for masses much larger than that observed for neutron stars could be significantly higher than that of Eq.

9 so that the energy

of the corresponding cosmic inflation could be larger. The quasi-scale invariant spectrum and quantum parity features observed in the CMB (see Gaztañaga and Sravan Kumar 2024)) will also be reproduced with our bouncing solution.

The ground state is approached asymptotically, with the density remaining constant even as the scale factor grows or decreases exponentially. This behaviour arises because the active mass m is no longer constant—a purely relativistic effect where the gravitational field itself contributes non-linearly to the source term. Consequently, the model transitions from a regime of constant energy-mass, characteristic of a Newtonian solution, to one of constant energy-density, which is inherently relativistic.

In summary, a bounce from degeneracy pressure could produce an epoch of cosmic inflation and has the potential to allow for nucleosynthesis and recombination, which is very similar to that in the standard Big Bang model. More importantly, it also offers an alternative route for understanding cosmic acceleration.

6. Cosmic Acceleration

There is compelling observational evidence that cosmic expansion is accelerating: (Riess et al. 1998; Schmidt et al. 1998; Perlmutter et al. 1999; Jimenez and Loeb 2002; Fosalba et al. 2003; Eisenstein et al. 2005; Betoule, M. et al. 2014). This acceleration appears to be dominated by . This term can be understood as a fundamental term, (a modification of GR) or an effective DE fluid similar to the ground state described above, but with a much smaller value for . Whatever the interpretation, the corresponding scale: is very large compared to the nuclear saturation scale (i.e. ) and therefore can be neglected for our discussion of the bounce and the corresponding inflationary period.

As mentioned above, the last integral in equation (

12) is needed in the cases where the manifold under study has a boundary. This is the case for the expanding solution (after the bounce) because this solution originates from the collapse into a BH. Once we cross inside the event horizon

, nothing can come out. This means that

becomes a boundary of the action. As shown in Gaztañaga (2023), for the FLRW cloud with total mass-energy

m, this term results in:

where

is the effective

term resulting from

. Note that this solution neglects the curvature because

is larger than

when the BH is formed. This provides a fundamentally different origin for

compared to

or

: it corresponds to a finite-mass FLRW cloud trapped inside its own gravitational radius

. This boundary interpretation for the observed

term corresponds to the Black Hole Universe (BHU) model. For

and

km/s/Mpc we have:

with the uncertainties from DESI Collaboration et al. (2024). As shown in Eq.

27, this value, together with

, gives us the minimum number of e-folds of inflation.

7. Conclusion

This work presents a robust theoretical framework for understanding the early Universe and its large-scale dynamics within the context of the Black Hole Universe (BHU) model. By analyzing the collapse and subsequent bounce of a spherically symmetric matter distribution, we demonstrate that, upon reaching a quantum ground state, the relativistic equation of state (EoS) transitions to . The pressure generated in this state halts the collapse and initiates a bounce. This mechanism parallels phenomena in neutron star physics and core-collapse supernovae (see reviews by Bethe 1990; Burrows et al. 1995; Hebeler et al. 2013; Janka et al. 2012), where the ground state is determined by nucleonic interaction potentials within proto-neutron stars. However, our implementation of the exclusion principle, rooted in general relativity, results in negative pressure—a distinctly relativistic phenomenon. This indicates that the active gravitational mass, unlike in classical frameworks, evolves non-linearly, increasing or decreasing exponentially in the comoving frame (see Gaztañaga (2024)). This same process drives an exponential expansion analogous to cosmic inflation, offering a novel solution to key challenges in standard cosmology, such as the horizon, flatness, and dark energy problems. Our findings highlight the profound implications of relativistic quantum principles in shaping the early Universe.

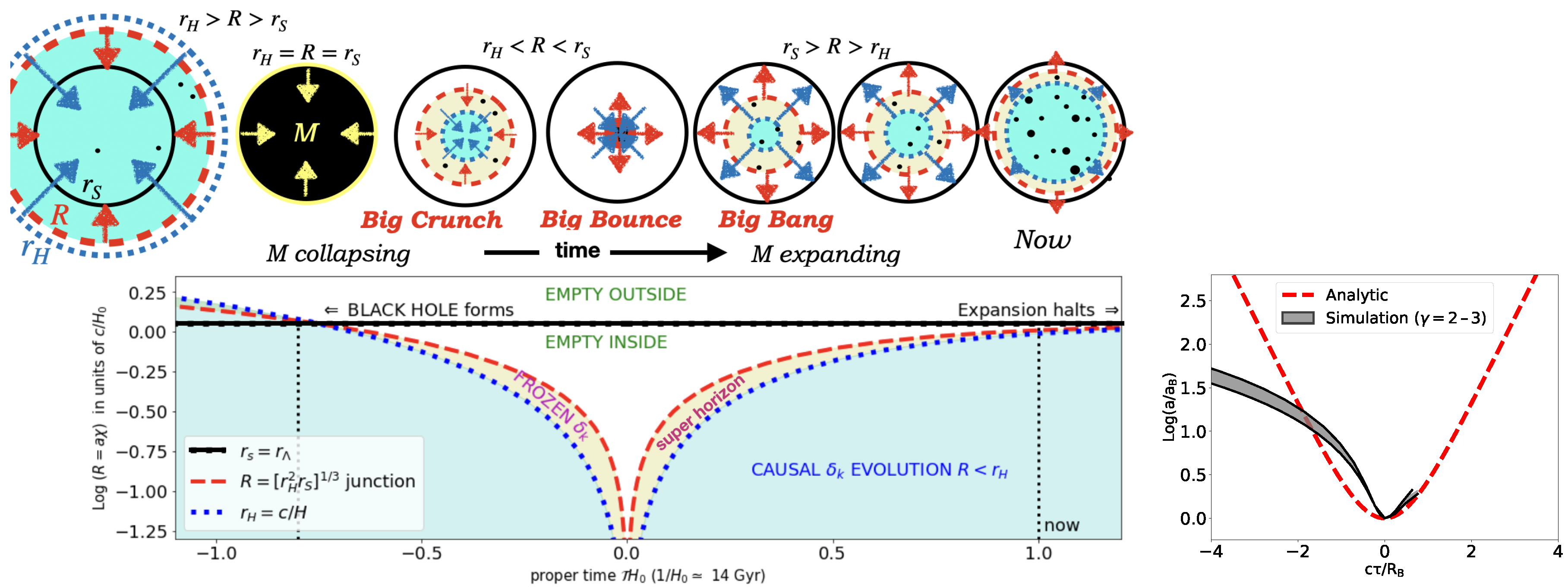

In

Figure 1, we show the full evolution for the radius of the FLRW cloud

, illustrating how the horizon problem is solved in the bounce model (Gaztañaga (2023)). The right panel shows a zoom over the bounce region with our asymptotic analytical solution compared to numerical Newtonian simulations in Pradhan et al. (2025), which use

. This kind of EoS can be a good approximation for nuclear degenerate matter with

to 3 (see Lattimer and Prakash 2007). Although our analytical model is only correct asymptotically (in the limit when we reach constant saturation density

) and the numerical solution is also an approximation, we see that both models can provide a very similar exponential expansion after the bounce.

The solution we found in Eq.

25 is one of the cases considered in Eq.7 in Starobinsky (1980), which corresponds to a de-Sitter Universe with closed curvature. Instead of degeneracy pressure, this model arises from quadratic curvature modification of the Einstein-Hilbert action motivated by 1-loop self-energy contributions due to quantum matter, which leads to the first model of cosmic inflation (Starobinskii 1979). But the reason to consider closed curvature (other than to produce a bounce as in Starobinskii 1978) is not clear in this model. In the BHU model, the spatial curvature naturally results from the spherical collapse of a large overdensity confined to a finite region of spacetime.

As detailed in Fig.3 of Gaztañaga (2022), the boundary

of such a cloud is always outside the observational window for any (off-centred) observer inside the cloud. This is a general property of quasi-de-Sitter space and implies that the BHU does not result in observed anisotropies in the background of the cloud boundary. But the bounce and the initial cloud’s comoving radius

can result in a cutoff of the super-horizon quantum perturbations generated during inflation, which can be observed in the CMB (Gaztañaga and Camacho-Quevedo 2022; Camacho-Quevedo and Gaztañaga 2022; Fosalba and Gaztañaga 2021) and results in the constraint given by Eq.

24. Such cutoff, together with parity asymmetry, predicts a lower quadrupole, which can explain several other CMB anomalies (see Gaztañaga and Sravan Kumar 2024,?; Gaztañaga et al. 2024).

Our analysis shows that the observed cosmological constant can be interpreted as a boundary effect from the gravitational radius of the BHU, aligning with the idea of an effective term without invoking exotic physics. The implications of this model extend to the generation of super-horizon perturbations, the observed entropy ratio of baryons to photons, and the potential origins of dark matter (Gaztañaga 2022). Future studies should explore the role of temperature, shock waves, radiation and nuclear reactions during the bounce to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the transition from collapse to expansion.

Data Availability Statement

No new data in this paper.

Acknowledgments

EG acknowledges grants from Spain Plan Nacional (PGC2018-102021-B-100) and Maria de Maeztu (CEX2020-001058-M). KSK acknowledges the support from the Royal Society the Newton International Fellowship. SP acknowledges the support and hospitality at the Institute of Cosmology and Gravitation during a 3-month stay to conclude his Master’s Thesis. MG acknowledges the support through the Generalitat Valenciana via the grant CIDEGENT/2019/031, the grant PID2021-127495NB-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Union, and the Astrophysics and High Energy Physics programme of the Generalitat Valenciana ASFAE/2022/026 funded by MCIN and the European Union NextGenerationEU (PRTR-C17.I1).

References

- Pradhan, S.; Gabler, M.; Gaztañaga, E. Cold collapse and bounce of a FLRW cloud. MNRAS, 2024; staf019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W.; Penrose, R.; Bondi, H. The singularities of gravitational collapse and cosmology. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences 1970, 314, 529–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaztañaga, E.; Camacho-Quevedo, B. What moves the heavens above? Physics Letters B 2022, 835, 137468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starobinskii, A.A. On a nonsingular isotropic cosmological model. Pisma v Astronomicheskii Zhurnal 1978, 4, 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Starobinsky, A.A. A new type of isotropic cosmological models without singularity. Physics Letters B 1980, 91, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenberger, R.; Peter, P. Bouncing Cosmologies: Progress and Problems. Foundations of Physics 2017, 47, 797–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S.; Odintsov, S.D.; Oikonomou, V.K. Modified gravity theories on a nutshell: Inflation, bounce and late-time evolution. Phys. Rep. 2017, 692, 1–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odintsov, S.D.; Oikonomou, V.K.; Fronimos, F.P.; Fasoulakos, K.V. Unification of a bounce with a viable dark energy era in Gauss-Bonnet gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2020, 102, 104042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, C.; Mohaddes, H. Quantum theory of the Lemaitre model for gravitational collapse. arXiv 2024, arXiv:gr-qc/2412.12947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaztañaga, E. How the Big Bang Ends Up Inside a Black Hole. Universe 2022, 8, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaztañaga, E. The mass of our observable Universe. MNRAS 2023, 521, L59–L63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaitre, G. The expanding universe. Annales Soc. Sci. Bruxelles A 1933, 53, 51–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misner, C.W.; Sharp, D.H. Relativistic Equations for Adiabatic, Spherically Symmetric Gravitational Collapse. Phys. Rev. 1964, 136, B571–B576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peebles, P.J.E. The large-scale structure of the universe, 1980.

- Gaztañaga, E. On the Interpretation of Cosmic Acceleration. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckey, W.M. The observable universe inside a black hole. American Journal of Physics 1994, 62, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. Gravitation; Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gaztañaga, E. The Black Hole Universe, Part I. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, J.W. Role of Conformal Three-Geometry in the Dynamics of Gravitation. Phy.Rev.Lett. 1972, 28, 1082–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, G.W.; Hawking, S.W. Cosmological event horizons, thermodynamics, and particle creation. PRD 1977, 15, 2738–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W.; Horowitz, G.T. The gravitational Hamiltonian, action, entropy and surface terms. Class Quantum Gravity 1996, 13, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. Cosmology; Oxford University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw, G.; etal. Two-Point Correlations in the COBE DMR Four-Year Anisotropy Maps. ApJl 1996, 464, L25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spergel, D.N.; Verde, L.; Peiris, H.V.; Komatsu, E.; Nolta, M.R.; Bennett, C.L.; Halpern, M.; Hinshaw, G.; Jarosik, N.; Kogut, A.; et al. First-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Determination of Cosmological Parameters. ApJs 2003, 148, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration. ; Akrami, Y.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Ballardini, M.; Band ay, A.J.; Barreiro, R.B.; Bartolo, N.; Basak, S.; et al. Planck 2018 results. VII. Isotropy and statistics of the CMB. A&A 2020, 641, A7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Quevedo, B.; Gaztañaga, E. A measurement of the scale of homogeneity in the early Universe. JCAP 2022, 2022, 044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steigman, G. Primordial Nucleosynthesis in the Precision Cosmology Era. ARNPS 2007, 57, 463–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaztañaga, E.; Sravan Kumar, K. Finding origins of CMB anomalies in the inflationary quantum fluctuations. JCAP 2024, 2024, 001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, A.G.; Filippenko, A.V.; Challis, P.; Clocchiatti, A.; Diercks, A.; Garnavich, P.M.; Gilliland, R.L.; Hogan, C.J.; Jha, S.; Kirshner, R.P.; et al. Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant. AJ 1998, 116, 1009–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, B.P.; Suntzeff, N.B.; Phillips, M.M.; Schommer, R.A.; Clocchiatti, A.; Kirshner, R.P.; Garnavich, P.; Challis, P.; Leibundgut, B.; Spyromilio, J.; et al. The High-Z Supernova Search: Measuring Cosmic Deceleration and Global Curvature of the Universe Using Type Ia Supernovae*. The Astrophysical Journal 1998, 507, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, S.; Aldering, G.; Goldhaber, G.; Knop, R.A.; Nugent, P.; Castro, P.G.; Deustua, S.; Fabbro, S.; Goobar, A.; Groom, D.E.; et al. Measurements of Ω and Λ from 42 High-Redshift Supernovae. The Astrophysical Journal 1999, 517, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, R.; Loeb, A. Constraining Cosmological Parameters Based on Relative Galaxy Ages. The Astrophysical Journal 2002, 573, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosalba, P.; Gaztañaga, E.; Castander, F.J. Detection of the Integrated Sachs-Wolfe and Sunyaev-Zeldovich Effects from the Cosmic Microwave Background-Galaxy Correlation. ApJL 2003, 597, L89–L92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstein, D.J.; Zehavi, I.; Hogg, D.W.; Scoccimarro, R.; Blanton, M.R.; Nichol, R.C.; Scranton, R.; Seo, H.J.; Tegmark, M.; Zheng, Z.; et al. Detection of the Baryon Acoustic Peak in the Large-Scale Correlation Function of SDSS Luminous Red Galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal 2005, 633, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betoule, M. .; Kessler, R..; Guy, J..; Mosher, J..; Hardin, D..; Biswas, R..; Astier, P..; El-Hage, P..; Konig, M..; Kuhlmann, S..; et al. Improved cosmological constraints from a joint analysis of the SDSS-II and SNLS supernova samples. A&A 2014, 568, A22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DESI Collaboration.; Adame, A.G.; Aguilar, J.; Ahlen, S.; Alam, S.; Alexander, D.M.; Alvarez, M.; Alves, O.; Anand, A.; Andrade, U.; et al. DESI 2024 VI: Cosmological Constraints from the Measurements of Baryon Acoustic Oscillations. arXiv 2024, arXiv:astro-ph.CO/2404.03002.

- Bethe, H.A. Supernova mechanisms. Reviews of Modern Physics 1990, 62, 801–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, A.; Hayes, J.; Fryxell, B.A. On the Nature of Core-Collapse Supernova Explosions. ApJ 1995, 450, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebeler, K.; Lattimer, J.M.; Pethick, C.J.; Schwenk, A. EQUATION OF STATE AND NEUTRON STAR PROPERTIES CONSTRAINED BY NUCLEAR PHYSICS AND OBSERVATION. ApJ 2013, 773, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janka, H.T.; Hanke, F.; Hüdepohl, L.; Marek, A.; Müller, B.; Obergaulinger, M. Core-collapse supernovae: Reflections and directions. Progress of Theoretical and Experimental Physics 2012, 2012, 01A309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattimer, J.M.; Prakash, M. Neutron star observations: Prognosis for equation of state constraints. PhysRep 2007, 442, 109–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starobinskii, A.A. Spectrum of relict gravitational radiation and the early state of the universe. ZhETF Pisma Redaktsiiu 1979, 30, 719–723. [Google Scholar]

- Fosalba, P.; Gaztañaga, E. Explaining cosmological anisotropy: evidence for causal horizons from CMB data. MNRAS 2021, 504, 5840–5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaztañaga, E.; Sravan Kumar, K. Unitary quantum gravitational physics and the CMB parity asymmetry. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaztañaga, E.; Sravan Kumar, K.; Marto, J. A New Understanding of Einstein-Rosen Bridges. preprint 2024, 2836794. [Google Scholar]

- Gaztañaga, E. The Black Hole Universe, Part II. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).