1. Introduction

The built environment constantly evolves, influenced by internal and external factors [

1]. Buildings that fail to adapt to these changes may require extensive renovation or early demolition, leading to obsolescence [

2,

3,

4].This obsolescence can increase waste generation, resource consumption, and environmental and economic concerns [

5,

6] .

Given these challenges, it becomes imperative to rethink how we manage the building's life-cycle. In an era of ambitious sustainability targets set by legislative bodies, demolition or extensive renovation should be a last resort [

7]. Preserving and extending the functional life of buildings can substantially contribute to achieving these sustainability targets [

8,

9,

10]. As highlighted by scholars, adaptable buildings offer crucial advantages in resource efficiency and longevity, requiring fewer materials and less energy to meet changing needs, thus reducing obsolescence [

1,

11,

12,

13].

Central to the concept of adaptability is the openness to change. Scholars define transformation capacity as a metric indicating how efficiently a building or its components can adapt to evolving needs and requirements .[

14] This capacity serves as an indicator of both adaptability and sustainable architecture [

15,

16]. However, diverse interpretations of adaptability, as highlighted by Schmidt III and Austin [

17]and Pinder et al. [

13] reveal the need for further research to bridge the gap and enhance our understanding of adaptability in construction.[

13,

18,

19,

20]

Adaptability enhances a building’s lifespan and transformation capacity by responding to variables and changing conditions, offering regenerative alternatives to today’s often obsolete buildings [

20,

21]. Designing adaptable buildings allows modifications in response to changing occupant needs or purposes without extensive and costly renovations, thereby increasing their overall value [

3,

22]. Property owners and investors favour adaptable buildings due to their added value, higher occupancy rates, and long-term market viability [

23].

Integrating specific considerations throughout the entire building process is essential to optimising the benefits of adaptability [

23,

24,

25]. This requires a successive commitment to incorporating adaptability into construction projects, with adjustments to design and planning as they evolve. Recognising adaptability as an ongoing process necessitates foresight, strategic planning, and deliberate decision-making to ensure buildings remain functional, efficient, and relevant over time.

Existing literature discusses adaptability in relation to design strategies [

15,

17] , but few studies offer a structured framework for embedding adaptability throughout the entire building process—from conceptual design to end-of-life consideration [

19,

26,

27]. This paper aims to address this gap by investigating how adaptability should be incorporated into the different stages of the building life-cycle. The approach involves analysing adaptability and its associated terminologies, focusing on the types of change they represent in buildings. This analysis thoroughly reviews the relationship between these adaptability considerations and the entire building life-cycle. This paper provides an outline for integrating adaptability into building design and construction processes by examining the specific terms and their broader implications..

2. Materials and Methods

This research employs a combination of systematic literature review and narrative review methodologies to provide a comprehensive exploration of adaptability within the building life cycle. The systematic review ensures a rigorous and transparent process for identifying and synthesising relevant literature, while the narrative review complements this by offering a qualitative, holistic interpretation informed by existing theories, models, and the researchers' expertise. Together, these approaches provide both breadth and depth in analysing the complexities of adaptability.

2.1. Systematic Review

A systematic review, characterised by its structured approach to literature retrieval and analysis, was conducted following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework [

28]. This approach included four phases: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion, ensuring a transparent and replicable process.

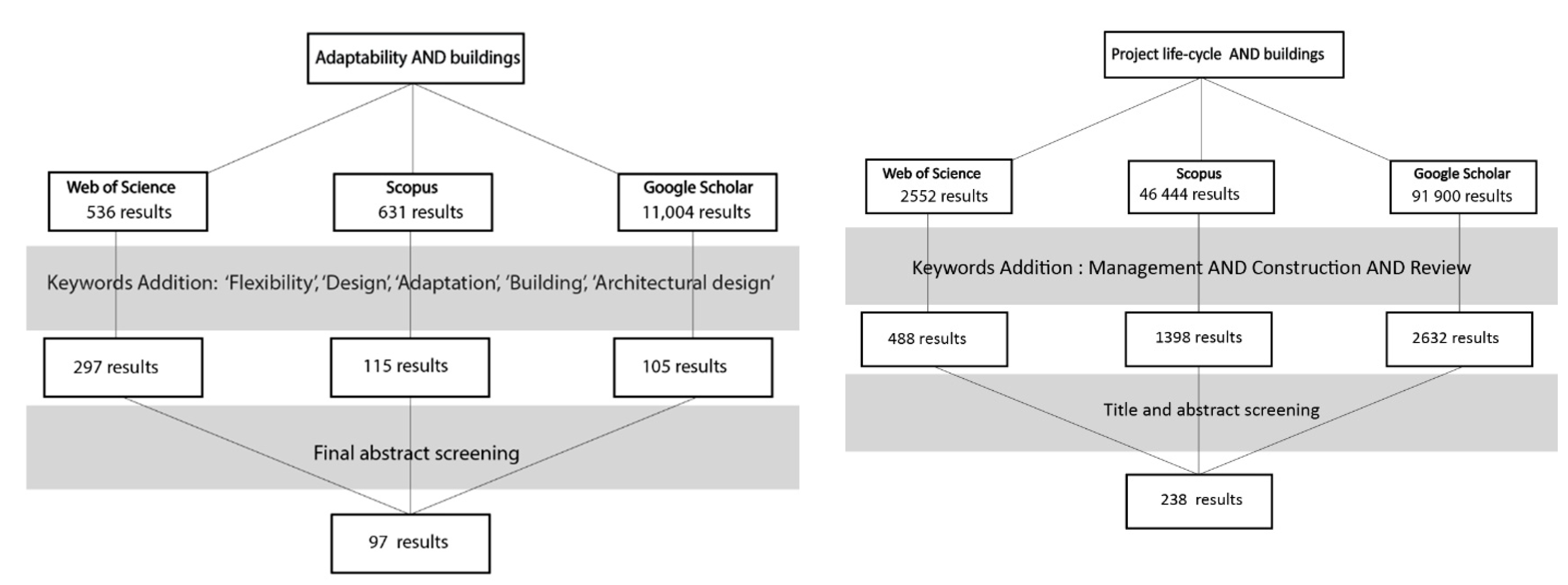

The indexed databases Scopus and Web of Science were utilised to ensure broad coverage of relevant academic literature. The search queries targeted titles, abstracts, and keywords in Scopus, and the “Topic” field—covering title, abstract, author keywords, and Keywords Plus®—in Web of Science. The queries focused on key phrases such as “Adaptability AND buildings” and “Project life cycle AND buildings”. Conducted in March 2024, the search yielded 97 articles on adaptability and 238 articles on the building life cycle (

Figure 1).

The review included peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, books, and book chapters published in English between 2013 and 2023. Articles without validated methodologies were excluded. Duplicate and irrelevant articles were also removed during the PRISMA stages.

2.2. Narrative Review

The narrative review complements the systematic approach by synthesising the findings from primary studies and contextualising them within broader theoretical and practical frameworks [

29]. Narrative reviews are particularly suited for addressing comprehensive and multifaceted topics like adaptability, where diverse perspectives and interpretations enrich understanding [

30] .This method enables incorporating qualitative techniques, such as meta-ethnography and phenomenography, to compare studies and add interpretive value [

31] .

2.3. Categorization and Refinement

Building on Schmidt and Austin’s [

17], categorisation of adaptability into six dimensions—task, space, performance, use, size, and location—this research refines the framework to focus on four principal dimensions: internal layout, function, components, and volume. The exclusion of location, typically determined during the conceptual phase, simplifies the applicability of adaptability principles across the building life cycle.

This refined categorisation integrates findings from the systematic and narrative reviews, offering a structured yet contextually enriched framework for understanding and applying adaptability in architectural practice. By combining these methodologies, the study ensures a robust and comprehensive exploration of adaptability, bridging theoretical insights and practical implementation throughout the building life cycle.

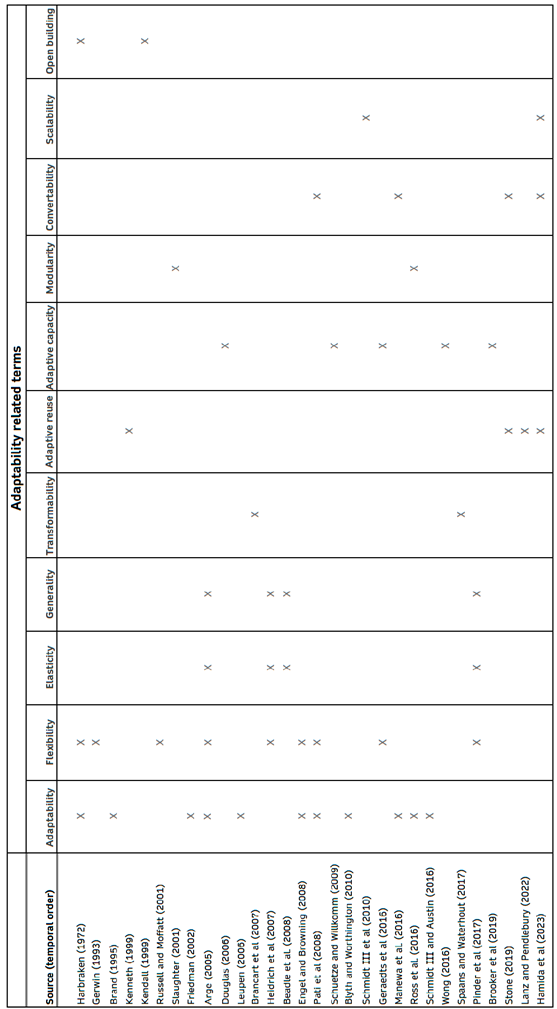

3. Results

The concept of adaptability is often misused and misunderstood [

13]. Scholars have noted that various interpretations lead to overlapping meanings and confusion [

20,

23,

32]. Moreover, there is a lack of clarity on when to incorporate adaptability into a building’s life- cycle despite its known impact on project outcomes [

16] .

This chapter attempts to clarify the concept of building adaptability by examining its different definitions and then emphasising the importance of integrating adaptability throughout all stages of the building life-cycle.

The first section reviews ten definitions of building adaptability and examines the type of change they represent. The second part explores the building's life-cycle, categorising it into ten phases and highlighting practical considerations for adaptability within each phase.

3.1. Adaptability

Building on the idea that adaptability is closely tied to evolution and change [

13] , is evident that adaptability is highly dependent on the specific context, and it varies across different fields. In the field of product design, for example, adaptability is often associated with extending a product’s service life [

33] or enabling products to adjust to differing requirements [

34]. In process design, adaptability is viewed as a strategy to overcome inherent limitations [

35]. This nuanced understanding of adaptability extends into the architectural domain, where scholars have systematically analysed and categorised the concept to enhance its applicability.

In their efforts to deepen the understanding of adaptability in the context of buildings, scholars have proposed dividing buildings into distinct layers [

17,

18,

36,

37]. According to Brand [

18] adaptability is dynamic and includes different lifespans for the various elements of the building. Friedman introduced adaptability in the context of the relationship between buildings and their users, defining it as the ability to accommodate various functions over time [

32]. Arge described it as the ability to change in response to internal or external factors [

3].

Other scholars tried to decipher adaptability in buildings by dividing it into the process of building and the building as the final product [

23,

24]. Adding an economic perspective, Blyth and Worthington defined adaptability as ‘The capacity of a building to react within a short time to new circumstances with minimal effort and at a justifiable cost’[

38]. Ross further expanded on this by describing adaptability as the ease with which buildings can be physically modified, deconstructed, and reconfigured [

39].

3.1.1. Flexibility

Flexibility represents the capacity to adapt to new conditions or circumstances [

40]. In the built environment, flexibility is vital for addressing uncertainties and adapting to evolving conditions.

Gerwin [

41]describes flexibility as the capacity to respond effectively to environmental uncertainties, emphasising the need for buildings to accommodate unforeseen changes during design and construction [

3,

41]. Engel and Browning further define flexibility as the ability to withstand stress without damage, highlighting the importance of resilience [

42].

Russell et al. [

43] characterise flexibility as facilitating minor shifts in space planning, enhancing adaptability without significant structural changes. This practical aspect of flexibility allows buildings to meet the changing needs of their interior layout with small adjustments [

43] (

Table 1).

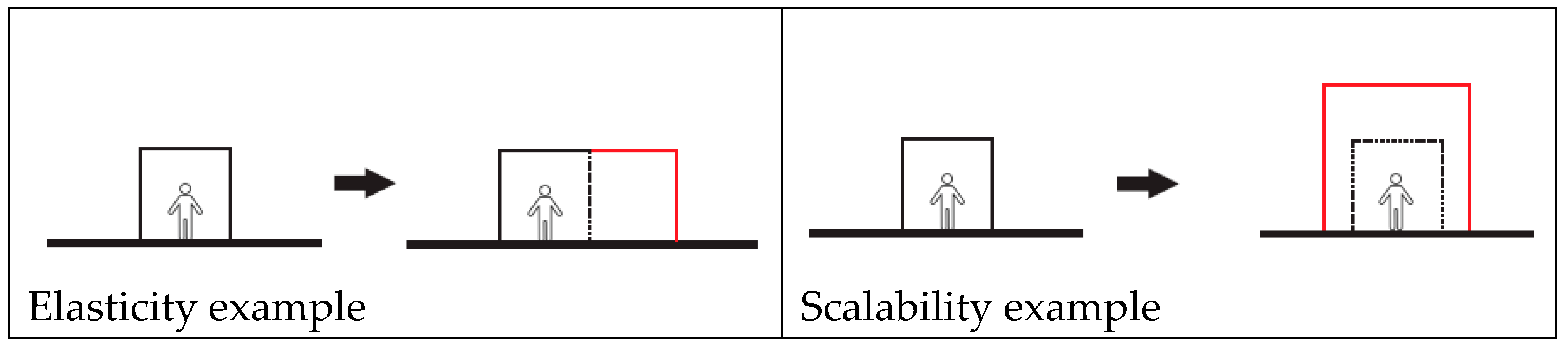

3.1.2. Elasticity

Elasticity encompasses two main aspects. The first definition pertains to the ability of a material to resume its initial form after being stretched or compressed. The second aspect refers to the ability to change or adapt [

40].

In building structures, elasticity represents how a material responds to forces or heat exposure, emphasising the stress or movement involved when it returns to its original form [

44]. In architectural discourse, elasticity extends beyond materials to encompass the building itself. It signifies a building’s capability to be extended, shrunk, or partitioned according to specific requirements, altering its volume [

3,

45] (

Table 1).

3.1.3. Generality

Generality refers to a condition encompassing a wide variety of elements rather than focusing on specific details [

40]. In architecture, this concept is particularly significant as it represents a building’s ability to fulfil changing functional purposes without altering its core properties [

3,

27,

45]. The essence of generality lies in its capacity to future-proof a structure, enabling its interior to adapt to diverse uses over time without requiring substantial structural modifications (

Table 1).

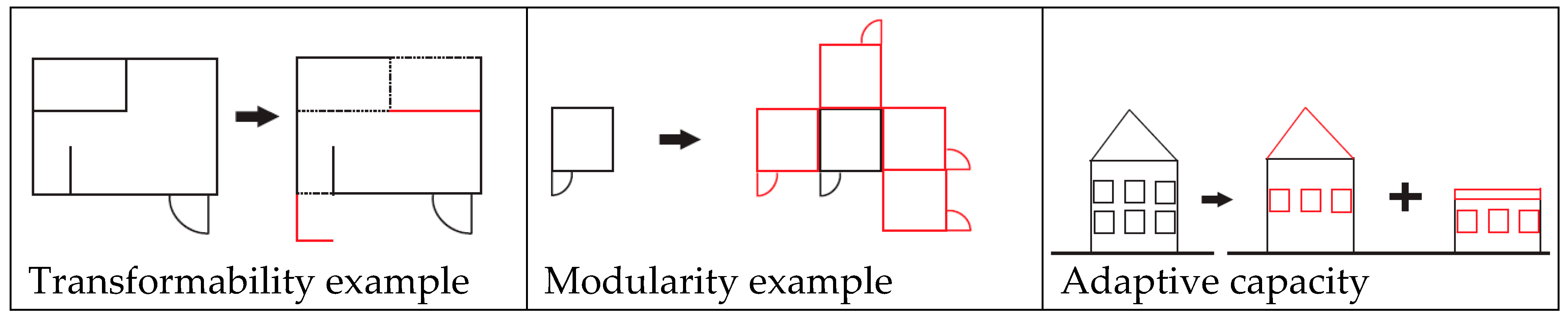

3.1.4. Transformability

Transformability is regarded as the ability to go beyond the existing trajectory and discover new ways of development [

46]. It is considered a crucial path towards resilience [

47].

Within the built environment, transformability is defined as a component’s capacity to assume a new function [

48]. This definition encapsulates the dynamic nature of certain elements within such systems, showcasing their ability to transition into different roles or functionalities in response to changing requirements or condition.

Brancart further elaborated on the concept of transformability in buildings by identifying two fundamental principles: deployability and design for disassembly [

49]. Deployability focuses on adapting a system’s components for efficient deployment, ensuring that they can be easily moved and reconfigured as needed. In contrast, design for disassembly emphasises strategic planning and construction of components to facilitate their disassembly when necessary, promoting adaptability and sustainability.

In essence, the concept of transformability encompasses both the inherent adaptability of components to assume new functions and the deliberate principles guiding their disassembly (

Table 1).

3.1.5. Adaptive Reuse

The term ‘adaptive reuse’ refers to repurposing buildings that have outlived the original function for which they were constructed [

50,

51]. Essentially, adaptive reuse is the process of transforming existing buildings to serve contemporary or different purposes [

2]

. This concept goes beyond merely altering a building’s physical structure; it involves a collaborative effort between the conservation community and the field of architecture to revitalise and reoccupy these structures [

51,

52].

Adaptive reuse breathes new life into buildings that have fulfilled their initial purpose [

22]. This process is collaborative and transformative, preserving architectural heritage while contributing to sustainable urban development. By repurposing existing resources to meet contemporary needs, adaptive reuse conserves materials, reduces waste and fosters a connection between historical architecture and modern functionality [

53]. This approach underscores the importance of sustainability in the built environment, ensuring that structures remain relevant and valuable over time without necessitating new construction (

Table 1).

3.1.6. Adaptive Capacity

Schuetze and Willkomm [

54], conceptualises adaptive capacity within the built environment as the intrinsic ability to accommodate diverse functions or adapt to changing requirements. This capacity is realised through the design and construction of components and products that enable efficient reuse and recycling with minimal effort while maintaining high-quality standards. As such, adaptive capacity serves as a central element in building circularity [

54] .

Building upon this foundation, Geraedts et al. [

23] extend the understanding of adaptive capacity by encompassing all characteristics that enable a structure to maintain functionality throughout its technical life cycle while withstanding changes in requirements and circumstances. This broader perspective categorises adaptive capacity into three integral dimensions: organisational flexibility, process flexibility, and product flexibility. Organisational flexibility pertains to the adaptability of the overall structure and its components to organisational changes. This involves the capacity of the building’s design to accommodate shifts in use or management practices without necessitating major structural alterations. Process flexibility involves adapting construction and operational processes to accommodate varying demands. This dimension focuses on the methods and procedures used during the building’s construction and operation phases, ensuring they are adaptable and can respond to changes efficiently. Product flexibility centres on the adaptability of the built product or structure itself to evolving functional requirements. This includes designing building components that can be easily modified, replaced, or repurposed to meet new demands [

23] (

Table 1).

3.1.7. Modularity

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, modularity is the quality of having separate parts that, when combined, form a complete whole [

55] .

Ross et al. [

39] and Slaughter [

5] have conceptualised modularity in the context of buildings. This concept involves standardising component sizes and interfaces to promote consistency and compatibility within a system or structure [

5,

39]. Using standardised elements in construction allows for more efficient and interchangeable building practices.

At a micro level, modularity can be applied to the assembly of individual rooms. Here, standardised components are used to create spaces that can be easily modified or reconfigured as needed. On a macro scale, modularity extends to entire buildings composed of standardised rooms or modules [

23]. This principle supports constructing large structures with consistent, interchangeable parts, facilitating easier expansion, renovation, or repurposing over time (

Table 1).

3.1.8. Convertibility

Convertibility is the ability to change into a different form or use [

40]. In buildings, this term explicitly denotes the capacity to transition between different functions or uses [

1,

13,

56]. This concept highlights the dynamic adaptability of buildings to serve various purposes, showcasing their versatility and flexibility in responding to changing requirements or evolving societal needs [

44] .

The significance of convertibility lies in its potential to mitigate the risk of obsolescence. By enabling buildings to evolve in response to shifting demands, convertibility ensures that structures remain relevant and functional over time, minimising the need for extensive renovations or demolitions (

Table 1).

3.1.9. Scalability

Scalability refers to a system’s ability to expand its capacity by including more elements, thereby increasing its size [

55]. In the field of architecture, scalability signifies the dynamic capacity of a building to adjust its size and volume, permitting both expansion and contraction as needed [

57] .

The core of scalability lies in its flexibility to meet diverse needs, whether that involves increasing or decreasing the overall dimensions of the building. This concept is crucial for accommodating varying space requirements over time, ensuring that the building can adapt to different uses and functions without necessitating major structural changes (

Table 1).

3.2. Open Building

N.J. Habraken and Valkenburg [

58] first introduced the open building concept, a term associated explicitly with architecture, in 1972. This concept implies designing buildings that can be precisely adjusted to meet users’ needs. Habraken’s approach involves dividing the building volume into two distinct layers: the ‘base building’ and the ‘infill’ [

58] .

The ‘base building’ refers to the fixed structure of the building, which includes the fundamental and permanent elements. In contrast, the ‘infill’ comprises the interior parts that can be rearranged and modified according to the users’ needs. This separation allows for greater flexibility and adaptability, enabling spaces to be easily transformed to accommodate changing requirements without altering the core structural framework [

59] (

Table 1).

In conclusion, adaptability can be defined as the ability to change in response to various stimuli, encompassing a broad spectrum of interpretations depending on the specific type of change accommodated. Scholars have extensively explored and categorised these interpretations, recognising that adaptability is not a monolithic concept but a multifaceted one (

Table 1).

3.3. Life-Cycle of a Building

Over the past four decades, the concept of the building life-cycle has undergone significant evolution, reflecting the increasing complexity and demands of construction projects [

60] .In the 1980s, scholars identified four primary phases in construction projects: conceptualisation, planning, production, and termination [

61,

62]. As research advanced, the model expanded to include a ‘use’ phase, while the original stages were refined into sub-phases to capture the nuanced processes within modern construction [

63,

64] .

The evolution of the building life cycle framework reflects the increasing complexity of construction projects and underscores the-need to address emerging challenges within the industry [

65]. Among these challenges, environmental sustainability has gained prominence as a central concern, prompting the integration of assessment tools and methodologies to evaluate buildings' ecological impact [

66,

67,

68,

69,

70].

The increasing emphasis on sustainability in the construction industry has driven the development and widespread adoption of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), a systematic methodology for evaluating the environmental impact of buildings throughout their entire life cycle [

66,

70,

71,

72,

73]. Anchored in standards such as EN 15804 and EN 15978, LCA provides a structured framework for analysing key lifecycle stages, focusing primarily on a building's physical attributes [

66]. These stages include the construction phase, subdivided into A1-A3 (material production) and A4-A5 (construction processes), the operational use phase (B1-B5), and the end-of-life phase (C1-C4), which addresses deconstruction, demolition, and material recovery or disposal [

74,

75] .

3.4. The Critical Role of Early Design Phases in Enhancing Sustainability and Adaptability

The LCA framework offers a structured methodology for evaluating the environmental impact of buildings across their physical life-cycle. However, it does not inherently encompass the early planning phases—namely, the concept and design phases—where critical decisions about materials, construction methods, and spatial configurations are made. These phases are pivotal, as they profoundly influence a building's operational performance, environmental impact, and overall design quality [

38,

76,

77,

78] .

Integrating LCA considerations into these early phases ensures that sustainability principles are embedded from the outset, minimising environmental impacts and aligning the design process with long-term sustainability goals [

68,

72].

By incorporating strategies for energy efficiency, material reuse, and adaptability into the concept and design phases, buildings can be better equipped to address future changes with minimal interventions. Early decisions to include modularity, disassembly, and transformability principles enable buildings to respond effectively to evolving societal, technological, or functional demands [

3,

32]. These strategies help reduce obsolescence, enhance flexibility, and extend the functional lifespan of buildings.

The significance of embedding adaptability criteria during these phases is widely emphasised in the literature [

79]. Scholars argue that early integration of adaptability is essential for creating sustainable, long-lasting buildings [

25,

79,

80]. Andrade and Bragança [

16]underscore that adaptability considerations at this phase can extend building life expectancy, reduce environmental impact, and support sustainability goals. Failure to address adaptability early can lead to structural challenges and increased costs in later lifecycle phases [

6,

16,

81,

82]. Strategic planning during the initial phases ensures that buildings are designed to accommodate future changes, thereby mitigating risks and reducing potential renovation expenses.

Neglecting adaptive reuse principles during these early phases further limits opportunities for disassembly and material reuse once a building reaches the end of its technical life. This omission undermines the potential for circular material use, a cornerstone of sustainable construction practices [

16,

25,

83]. Early integration of adaptive reuse strategies allows architects and engineers to design buildings with future material recovery and reuse in mind, thus enhancing circularity and contributing to more sustainable construction projects [

6,

82,

84]. Incorporating these principles ensures that buildings meet current needs and are resilient and adaptable to future demands.

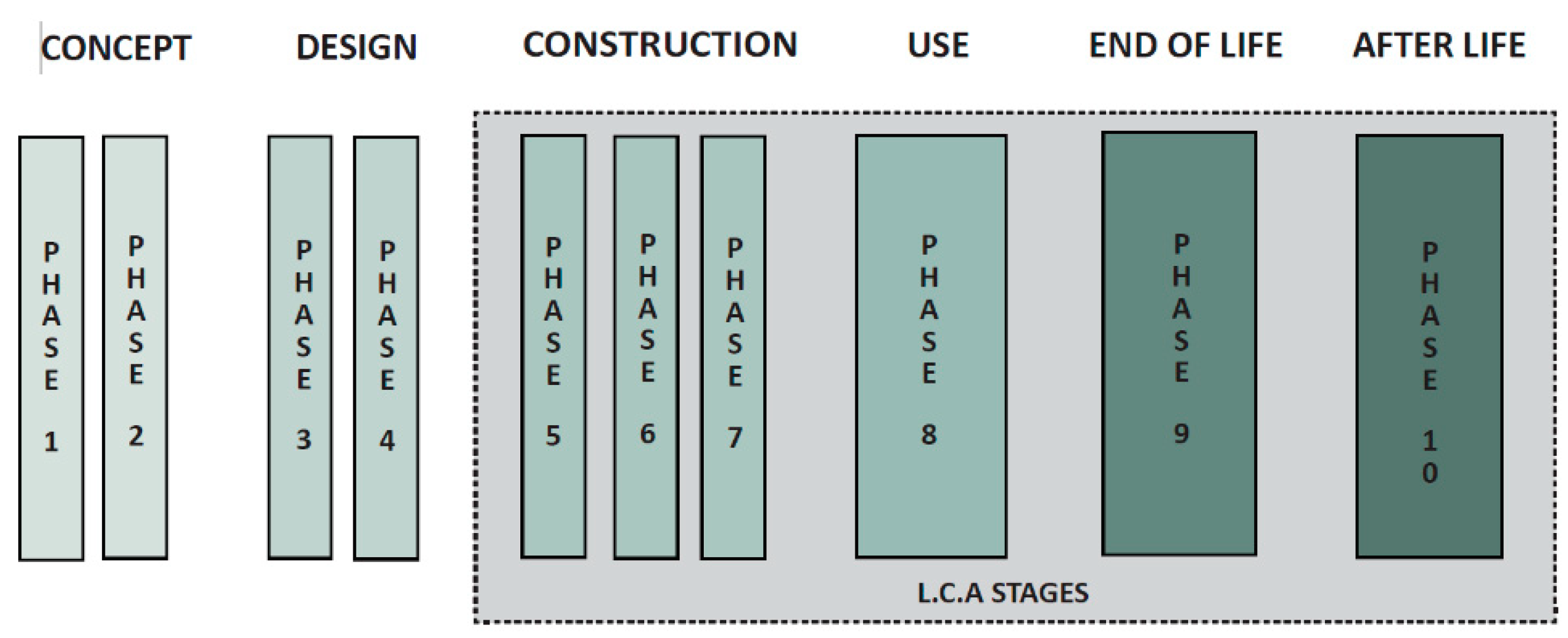

3.5. Building Life-Cycle and Adaptability Considerations

The building life-cycle offers multiple opportunities to integrate adaptability strategies, which play a crucial role in mitigating obsolescence, minimising the need for costly renovations, and enhancing sustainability. This study segments the building life cycle into ten distinct phases, encompassing both the early planning and conceptual stages [

61] , as well as the physical stages defined by LCA [

75]. By examining how adaptability considerations can be embedded at each phase, the study highlights strategies to foster resilience and promote circularity. This comprehensive approach ensures that adaptability is addressed holistically, aligning the initial design and planning processes with the practical and environmental demands of the building’s physical lifecycle (

Figure 2).

Phase 1: Initiation

In the initial phase of project development, the clients decide on the type of building and its location. Practical adaptability strategies focus primarily on design modifications and building considerations, so they are not yet applicable during this phase [

20] (

Table 2).

Phase 2: Feasibility & Project Brief

In phase 2 of the building life-cycle, the intentions for the building are established [

85]. At this phase, all the considerations for an adaptable building are defined [

20]. A feasibility study is conducted to assess the project viability, and the project brief is developed, often determining the type of adaptability required [

64] (

Table 2).

Phase 3: Architectural Concept

The concept phase is crucial for determining the architectural form of the building. It serves as the foundation for setting all criteria concerning the future building During this phase, construction, strategic, and technical adaptability criteria are established, and the initial building volume takes shape [

86,

87,

88]. Additionally, the conceptual framework for the building’s afterlife is developed during this phase [

89] (

Table 2).

Phase 4: Design

In the design phase, adaptability criteria materialise through collaboration between architects and engineers. Practical elements for the adaptable building are decided upon, and predictions about its future use are made. This phase involves finalising the adaptable design, determining future uses, selecting scalable infrastructure, and choosing future building materials [

3,

19,

22,

59,

90]. If the building follows adaptive capacity criteria, architects and engineers must design all elements to facilitate easy disassembly [

54,

83,

89]. Additionally, consideration of aesthetics, legislation, environmental strategies, constructional challenges, structural aspects, and economic factors is imperative to achieve a holistic, adaptable building [

20,

21,

84,

91] (

Table 2).

Phase 5 : Manufacturing

This phase encompasses the production and transportation of materials, including raw material extraction, processing, and delivery to the construction [

75,

92]. Adaptability strategies can be integrated at the component level by prioritising components that facilitate modularity, disassembly, and reuse. Materials designed to support these strategies enhance the potential for future reconfiguration or recycling of the building’s elements [

93].

Phase 6: Construction

As construction proceeds, the physical assembly of the structure begins. This phase is where adaptability strategies are manifested by selecting appropriate building components and materials [

93,

94]. In addition, allowing assembly tolerance during this phase can ensure the maintenance of adaptability during the building’s life cycle [

90] (

Table 2).

Phase 7: Handover

In the handover phase, the building is officially handed over, marking the termination of the construction process. During this phase, all envisioned targets, including adaptability strategies, are validated and implemented [

95]. A thorough inspection ensures that all elements are in place and functioning correctly before occupancy. The handover phase confirms that the building meets specified requirements and standards and is ready for use while accommodating future adaptability needs [

95] (

Table 2).

Phase 8: Use

The use phase signifies the occupancy of the building by its users, marking the transition from construction to practical use. At this phase, adaptability strategies are actively employed to adjust the building to varying needs, thereby extending its lifespan [

11,

13]. The building undergoes extensions, transformations, and alterations in response to different internal and external factors [

3]. This phase ensures that the building remains functional and relevant, accommodating changes in usage and requirements over time as originally envisioned (

Table 2).

Phase 9: End of Life

In the final phase, the building’s technical life-cycle concludes, opening opportunities for alternative uses beyond its original design through adaptive reuse or recycling and deconstruction possibilities facilitated by circularity principles [

22,

50,

54] (

Table 2).

Phase 10 : Afterlife

Incorporating an afterlife phase into the building’s life-cycle significantly reduces the potential for obsolescence. This approach ensures that the building’s materials and components can be repurposed, recycled, or safely deconstructed, thereby extending the building’s overall lifespan and minimising environmental impact [

75] (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

Adaptability in architecture is a complex concept, resulting in inconsistencies in interpretation and application [

13,

26,

104]. It functions as an umbrella term encompassing a range of related subcategories, each representing distinct types of change [

20]. These aspects include flexibility, generality, open-plan design, convertibility, adaptive reuse, transformability, modularity, and adaptive capacity, all reflecting the various dimensions of how buildings respond to changing requirements, emphasising the breadth and complexity of adaptability as a concept.

To enhance understanding, scholars have sought to categorise adaptability based on the types of change it [

3,

23,

58]. Schmidt and Austin [

17] , identified six types of change: task, space, performance, use, size, and location. Building on this framework, this research refines the categorisation to focus on four principal dimensions: internal layout, function, components, and volume. Location, typically predetermined during a project's conceptual phase, is excluded from this analysis. By consolidating the remaining categories, the proposed approach simplifies the application of adaptability in architectural practice, ensuring a more structured and comprehensive integration throughout the design phase.

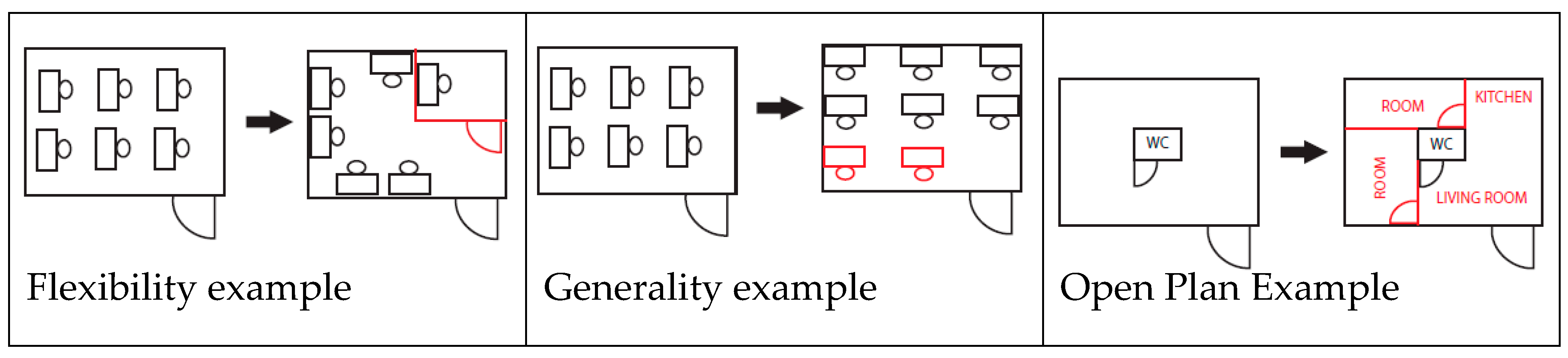

4.1. Internal Layout-Related Terms

Scholars have identified several key terms related to adaptability in building design, each emphasising different degrees and types of internal spatial changes. The three terms—flexibility, generality, and open building—focus on facilitating change within a building’s internal layout, during the use phase of the building life cycle. The primary distinction among them lies in the extent of change they accommodate.

Flexibility refers to spaces designed with the anticipation of future additions or modifications [

3,

42,

43]. This concept requires consideration of potential structural elements that might be needed later, such as additional support beams or infrastructure capacity for new systems.

As far as generality is concerned, changes are minimal and do not affect the core properties of the building [

3,

27,

45]. The design aims to maintain the building’s structural and aesthetic integrity while allowing various uses. This typically involves creating versatile, multi-use spaces that require little alteration to switch functions.

The open-plan approach allows for the most significant potential changes. By creating a fixed external shell with a non-specific internal layout, the building can undergo extensive internal reconfiguration [

58]. This concept is ideal for environments where spaces’ functions are expected to change frequently and substantially over time (

Figure 3).

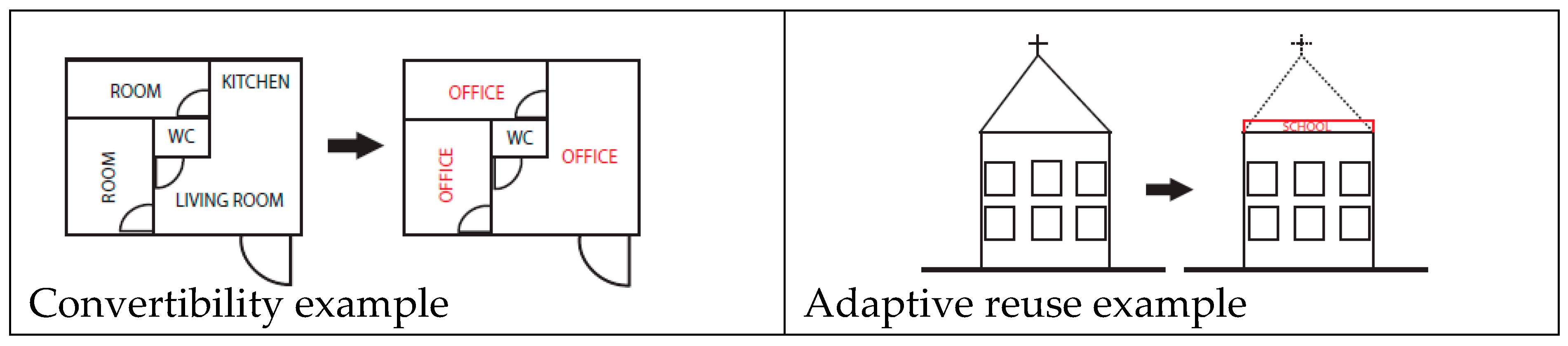

4.2. Function-Related Terms

Convertibility and adaptive reuse are two key concepts related to building functional adaptability. Each addresses different stages of a building’s life-cycle. Convertibility refers to a building’s capability to change its function during its active use phase. Buildings designed with convertibility in mind are intended to adapt to different uses as needs evolve over time [

1]. This adaptability-related term allows for functional shifts within the building’s original lifespan, enabling it to accommodate various purposes without significant structural changes.

In contrast, adaptive reuse pertains to the change in function that occurs after the building’s original use phase has concluded [

2] , during what is often referred to as the building’s ‘afterlife.’ This approach focuses on repurposing and revitalising buildings that might otherwise be demolished, giving them a new lease of life by transforming them for different uses beyond their initial design.

While both convertibility and adaptive reuse aim to extend the functional life of buildings through changes in use, they operate at different points in the building’s life cycle. Convertibility allows for functional shifts during the building’s active use phase, facilitating ongoing adaptability to meet current needs. On the other hand, adaptive reuse repurposes buildings after their initial use phase has ended, ensuring that existing structures are utilised efficiently and sustainably rather than being torn down. By addressing both active use and post-use phases, these concepts contribute to the sustainable management of the built environment (

Figure 4).

4.3. Component-Related Terms

Transformability, modularity, and adaptive capacity represent different approaches to designing buildings with adaptable components.

Modularity focuses on standardised components for efficient construction and easy modification [

5], making it suitable for buildings requiring frequent changes or expansions during the use phase. Transformability emphasises designing components that can assume new functions [

49] both during the use and after-life phase, enabling spaces to be repurposed as needs evolve. Adaptive capacity involves designing with the future reuse of components in mind during its after-life phase [

54], promoting sustainability and resource efficiency.

In conclusion, all three terms refer to building components but differ in the type of change they offer: modularity allows for quick construction and flexible reconfiguration, transformability enables buildings to adapt to different functions without significant alterations, and adaptive capacity ensures the long-term sustainability of materials (

Figure 5).

4.4. Volumetric-Related Terms

Two important concepts when considering changes in building volume are scalability and elasticity. Both terms pertain to the building’s ability to adapt its physical volume during the use phase of the building life cycle, but they differ in their approaches and implications for long-term use.

Scalability involves permanent adjustments to the building’s volume [

57]. Once the building changes its physical volume, the new additions become a fixed part of its structure.

When designing with elasticity in mind, temporary changes in building volume should be considered, allowing the structure to expand and contract as needed [

3] .This adaptability strategy is advantageous for buildings that need to adapt quickly to changing spatial requirements.

In summary, scalability and elasticity are critical concepts for managing changes in building volume. Scalability focuses on permanent expansions to meet long-term needs, while elasticity provides the adaptability to adjust space temporarily and revert to the original form (

Figure 6).

4.5. Implementation of Adaptability in the Building Phases

Adaptability in building design is often addressed reactively, introduced in fragmented responses to evolving needs rather than as a cohesive design principle [

26]. To address this concern, adaptability considerations should be embedded early in the conceptual phase [

16,

21] (Phase 2), where projections for the building’s future adaptability and sustainability are first outlined and continue to be applied throughout the whole building cycle.

The design phase (Phases 3 and 4) is widely regarded as an essential phase in the development of an adaptable building [

23]. During this phase, architects and engineers define and integrate design criteria aligned with the selected adaptability considerations [

98]. This phase involves making strategic decisions to accommodate changes in the internal layout, function, volume, and components and considering the building’s afterlife [

20,

21,

103]

. To accommodate internal layout changes, designs should incorporate surplus space, increased ceiling heights, and scalable technical systems, such as oversized ventilation shafts, while using lightweight, demountable partition materials for flexibility and minimal disruption [

3,

23,

39]. Functional adaptability can be achieved through open-plan layouts and flexible technical systems, enabling seamless reconfiguration to meet changing user needs [

3,

23]. At the component level, modular construction and standardised components allow for efficient replacement, upgrading, and reconfiguration, while durable, reusable materials ensure long-term performance and sustainability [

5,

93]. For volumetric adaptability, robust structural systems and advanced joining techniques enable future expansions, such as adding floors, without compromising structural integrity [

39,

105] .

During the construction phase (Phases 5 , 6 and 7), the building takes shape through manufacturing and assembly [

93]. While many adaptability elements are predetermined in the earlier phases, adjustments can be made to accommodate unexpected changes or deviations from the original designs [

106].

In the use phase, adaptability related to the internal layout, function, volume, and components becomes essential. The building is now changed, allowing it to adjust to new requirements and extend its life-cycle [

13].

Finally, in the afterlife phase, the building ends its technical life. This is where adaptive capacity and reuse are crucial, either giving the building a new purpose or repurposing its components for new construction projects [

22,

103].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, adaptability is a fundamental concept in contemporary building design, serving as a cornerstone for creating functional, resilient, and sustainable structures. To fully harness its potential, adaptability must be embedded as a guiding principle across all phases of the building life cycle, from the initial conceptualisation to the building’s afterlife.

The conceptual and design phases are particularly critical, as decisions made at these early stages establish the foundation for a building’s future adaptability and sustainability. Architects, therefore, need to anticipate the types of changes their buildings may face over time and design accordingly. Whether these changes relate to internal layout, function, components, or volume, embedding adaptability ensures that buildings remain responsive to evolving needs with minimal structural or technical disruptions.

Equally significant is the afterlife phase, where strategies for repurposing or reusing building components can minimise waste and support circular economy principles. Adaptability must be viewed as a continuous process that spans the entire building life cycle, avoiding fragmented, ad-hoc implementations that compromise its long-term benefits.

This study categorises adaptability into four dimensions—internal layout, function, components, and volume—based on the types of change it represents. Integrating adaptability across these dimensions ensures that buildings can evolve alongside changing societal, functional, and environmental demands, reducing the risk of obsolescence and enhancing resilience.

Future research is essential to understand stakeholders' perspectives—including architects, engineers, policymakers, and end-users—and will be crucial for developing comprehensive frameworks that bridge the gap between adaptability theory and practice. By embracing adaptability as a cohesive and ongoing principle, architects and other professionals can create buildings that meet present needs and are prepared to address future uncertainties.

Funding

The APC was funded by REALTEK, Norwegian University of Life Sciences(NMBU)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Manewa, A., et al., Adaptable buildings for sustainable built environment. Built Environment Project and Asset Management, 2016. 6(2). [CrossRef]

- Kenneth, P., Architecture Reborn, the Conservation and Reconstruction of Old Buildings. 1999, Laurence King Publishing, London.

- Arge, K., Adaptable office buildings: theory and practice. Facilities, 2005. 23(3/4): p. 119-127. [CrossRef]

- Lemer, A.C., Infrastructure obsolescence and design service life. Journal of infrastructure systems, 1996. 2(4): p. 153-161. [CrossRef]

- Slaughter, E.S., Design strategies to increase building flexibility. Building Research & Information, 2001. 29(3): p. 208-217. [CrossRef]

- Webster, M.D., Structural design for adaptability and deconstruction: a strategy for closing the materials loop and increasing building value, in New horizons and better practices. 2007. p. 1-6.

- Gosling, J., et al., Adaptable buildings: A systems approach. Sustainable Cities and Society, 2013. 7: p. 44-51. [CrossRef]

- Arrigoni, A., et al., Life cycle environmental benefits of a forward-thinking design phase for buildings: the case study of a temporary pavilion built for an international exhibition. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2018. 187: p. 974-983. [CrossRef]

- Citherlet, S. and T. Defaux, Energy and environmental comparison of three variants of a family house during its whole life span. Building and environment, 2007. 42(2): p. 591-598. [CrossRef]

- Power, A., Does demolition or refurbishment of old and inefficient homes help to increase our environmental, social and economic viability? Energy policy, 2008. 36(12): p. 4487-4501. [CrossRef]

- van Ellen, L.A., et al., Rhythmic Buildings- a framework for sustainable adaptable architecture. Building and Environment, 2021. 203: p. 108068. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.J., K. James, and R. Reed, Using building adaptation to deliver sustainability in Australia. Structural Survey, 2009. 27(1): p. 46-61. [CrossRef]

- Pinder, J.A., et al., What is meant by adaptability in buildings? Facilities, 2017. 35(1/2): p. 2-20.

- Henrotay, C. BAMB 2020. 2015; Buildings As Material Banks]. Available from: https://www.bamb2020.eu/topics/circular-built-environement/common-language/transformation-capacity/#:~:text=Transformation%20capacity%20is%20a%20measure%20that%20expresses%20the,its%20parts%20to%20meet%20changing%20needs%20and%20requirements.

- Durmisevic, E., Transformable Building Structures. Design for disassembly as a way to introduce sustainable engineering to building design & construction. 2006, Delft University.

- Andrade, J.B. and L. Bragança. Assessing buildings’ adaptability at early design stages. in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2019. IOP Publishing.

- Schmidt III, R. and S. Austin, Adaptable architecture: Theory and practice. 2016: Routledge.

- Brand, S., How buildings learn: What happens after they're built. 1995: Penguin.

- Geraedts, R., FLEX 4.0, a practical instrument to assess the adaptive capacity of buildings. Energy Procedia, 2016. 96: p. 568-579. [CrossRef]

- Askar, R., L. Bragança, and H. Gervásio, Adaptability of Buildings: A Critical Review on the Concept Evolution. Applied Sciences, 2021. 11(10): p. 4483. [CrossRef]

- Kamara, J.M., et al., Change Factors and the Adaptability of Buildings. Sustainability, 2020. 12(16): p. 6585. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J., Building adaptation. 2006: Routledge.

- Geraedts, R., N.O. Olsson, and G.K. Hansen, Adaptability, in Facilities Management and Corporate Real Estate Management as Value Drivers. 2016, Routledge. p. 193-221.

- Gil, N., et al., Embodying product and process flexibility to cope with challenging project deliveries. Journal of construction engineering and management, 2005. 131(4): p. 439-448. [CrossRef]

- Dams, B., et al., A circular construction evaluation framework to promote designing for disassembly and adaptability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2021. 316: p. 128122. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt III, R., J. Deamer, and S. Austin. Understanding adaptability through layer dependencies. in DS 68-10: Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED 11), Impacting Society through Engineering Design, Vol. 10: Design Methods and Tools pt. 2, Lyngby/Copenhagen, Denmark, 15.-19.08. 2011. 2011.

- Heidrich, O., et al., A critical review of the developments in building adaptability. International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation, 2017. 35(4): p. 284-303. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., et al., Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of internal medicine, 2009. 151(4): p. 264-269.

- Kirkevold, M., Integrative nursing research—an important strategy to further the development of nursing science and nursing practice. Journal of advanced nursing, 1997. 25(5): p. 977-984. [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.A. and B.C. Fauser, Balancing the strengths of systematic and narrative reviews. 2005, Oxford University Press. p. 103-104. [CrossRef]

- Jones, K., Mission drift in qualitative research, or moving toward a systematic review of qualitative studies, moving back to a more systematic narrative review. Qualitative Report, 2004. 9(1): p. 95-112. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A., The adaptable house. 2002: McGraw-Hill, Inc.

- Gu, P., M. Hashemian, and A.Y.C. Nee, Adaptable Design. CIRP Annals, 2004. 53(2): p. 539-557.

- Li, Y., D. Xue, and P. Gu, Design for Product Adaptability. Concurrent Engineering, 2008. 16(3): p. 221-232. [CrossRef]

- Bravetti, M., et al., Adaptable processes. Logical methods in computer science, 2012. 8.

- Leupen, B., Frame and generic space. 2006: 010 Publishers.

- Duffy, F., Measuring building performance. Facilities, 1990. 8(5): p. 17-20.

- Blyth, A. and J. Worthington, Managing the brief for better design. Hoboken. 2010, NJ: Taylor and Francis.

- Ross, B.E., et al., Enabling Adaptable Buildings: Results of a Preliminary Expert Survey. Procedia Engineering, 2016. 145: p. 420-427. [CrossRef]

- Oxford, D., Oxford English Dictionary. 2023.

- Gerwin, D., Manufacturing flexibility: a strategic perspective. Management science, 1993. 39(4): p. 395-410. [CrossRef]

- Engel, A. and T.R. Browning, Designing systems for adaptability by means of architecture options. Systems Engineering, 2008. 11(2): p. 125-146. [CrossRef]

- Russell, P. and S. Moffatt, Assessing buildings for adaptability, IEA Annex 31 Energy-Related Environmental Impact of Buildings. International Initiative for a Sustainable Built Environment (iiSBE), ON, available at: http://annex31.wiwi.unikarlsruhe.de/pdf (accessed May 2013), 2001.

- Barber, J.R., Introduction, in Elasticity, J.R. Barber, Editor. 2010, Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht. p. 3-24.

- Beadle, K., et al. Adaptable futures: Sustainable aspects of adaptable buildings. in ARCOM (Association of Researchers in Construction Management) Twenty-Fourth Annual Conference. 2008.

- Folke, C., et al., Resilience Thinking Integrating Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability. Ecology and Society, 2010. 15(4).

- Walker, B., et al., Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecology and society, 2004. 9(2).

- Spaans, M. and B. Waterhout, Building up resilience in cities worldwide–Rotterdam as participant in the 100 Resilient Cities Programme. Cities, 2017. 61: p. 109-116. [CrossRef]

- Brancart, S., et al., Transformable structures: Materialising design for change. International Journal of Design & Nature and Ecodynamics, 2017. 12(3): p. 357-366. [CrossRef]

- Stone, S., UnDoing buildings: Adaptive reuse and cultural memory. 2019: Routledge.

- Wong, L., Adaptive reuse: extending the lives of buildings. 2016: Birkhäuser.

- Lanz, F. and J. Pendlebury, Adaptive reuse: a critical review. The Journal of Architecture, 2022. 27(2-3): p. 441-462. [CrossRef]

- Brooker, G. and S. Stone, Re-readings: 2: Interior architecture and the principles of remodelling existing buildings. 2019: RIBA publishing.

- Schuetze, T. and D. Willkomm. Designing Extended Lifecycles. in SASBE 09-3rd CIB International Conference on smart and sustainable built environments. 2009. CIB & TU Delft.

- Cambridge, P., Cambridge dictionary. 2024: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/adaptability.

- Pati, D., T. Harvey, and C. Cason, Inpatient unit flexibility: Design characteristics of a successful flexible unit. Environment and Behavior, 2008. 40(2): p. 205-232.

- Schmidt III, R., et al., What is the meaning of adaptability in the building industry. Open and Sustainable Building, 2010: p. 233-42.

- Habraken, N.J. and B. VALKENBURG, De Dragers en de Mensen. Supports: an Alternative to Mass Housing ... Translated ... by B. Valkenburg. 1972: Architectural Press.

- Kendall, S., Open building: an approach to sustainable architecture. Journal of Urban Technology, 1999. 6(3): p. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Lafhaj, Z., et al., Complexity in Construction Projects: A Literature Review. Buildings, 2024. 14(3): p. 680. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.K. and D.P. Slevin. Critical success factors across the project life cycle. 1988. Project Management Institute Drexel Hill, PA.

- Cleland, D.I., Systems analysis and project management. 1983. [CrossRef]

- Fowler, M. and J. Highsmith, The agile manifesto. Software development, 2001. 9(8): p. 28-35.

- 64. RIBA. RIBA Plan of Work 2020 [cited 2023; Available from: https://www.architecture.com/knowledge-and-resources/resources-landing-page/riba-plan-of-work.

- Evbuomwan, N.F. and C.J. Anumba, An integrated framework for concurrent life-cycle design and construction. Advances in engineering software, 1998. 29(7-9): p. 587-597. [CrossRef]

- Guinée, J.B., et al., Life cycle assessment: past, present, and future. 2011, ACS Publications. [CrossRef]

- Loiseau, E., et al., Green economy and related concepts: An overview. Journal of cleaner production, 2016. 139: p. 361-371. [CrossRef]

- Röck, M., et al., LCA and BIM: Visualization of environmental potentials in building construction at early design stages. Building and environment, 2018. 140: p. 153-161. [CrossRef]

- Potrč Obrecht, T., et al., BIM and LCA integration: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 2020. 12(14): p. 5534. [CrossRef]

- Bhyan, P., B. Shrivastava, and N. Kumar, Systematic literature review of life cycle sustainability assessment system for residential buildings: using bibliometric analysis 2000–2020. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 2023. 25(12): p. 13637-13665. [CrossRef]

- Vilches, A., A. Garcia-Martinez, and B. Sanchez-Montanes, Life cycle assessment (LCA) of building refurbishment: A literature review. Energy and Buildings, 2017. 135: p. 286-301. [CrossRef]

- Bribián, I.Z., A.A. Usón, and S. Scarpellini, Life cycle assessment in buildings: State-of-the-art and simplified LCA methodology as a complement for building certification. Building and environment, 2009. 44(12): p. 2510-2520. [CrossRef]

- Nwodo, M.N. and C.J. Anumba, A review of life cycle assessment of buildings using a systematic approach. Building and Environment, 2019. 162: p. 106290. [CrossRef]

- Bjørn, A., et al., LCA history. Life cycle assessment: theory and practice, 2018: p. 17-30.

- .

- Kovacic, I. and V. Zoller, Building life cycle optimization tools for early design phases. Energy, 2015. 92: p. 409-419. [CrossRef]

- Bogenstätter, U., Prediction and optimization of life-cycle costs in early design. Building Research & Information, 2000. 28(5-6): p. 376-386. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Q., et al., A fuzzy quality function deployment system for buildable design decision-makings. Automation in Construction, 2003. 12(4): p. 381-393. [CrossRef]

- Boge, K., et al., Failing to plan - planning to fail : how early phase planning can improve buildingsʼ lifetime value creation. Facilities, 2018.

- Hashemian, M., Design for adaptability. 2005, University of Saskatchewan.

- Israelsson, N. and B. Hansson, Factors influencing flexibility in buildings. Structural Survey, 2009. 27(2): p. 138-147.

- Pinder, J., R.S. III, and J. Saker, Stakeholder perspectives on developing more adaptable buildings. Construction Management and Economics, 2013. 31(5): p. 440-459.

- Durmisevic, E., et al. Development of a conceptual digital deconstruction platform with integrated Reversible BIM to aid decision making and facilitate a circular economy. in Proceedings of the Joint Conference CIB W78-LDAC, Luxembourg. 2021.

- Hamida, M.B., et al., Circular building adaptability and its determinants–A literature review. International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation, 2023. 41(6): p. 47-69. [CrossRef]

- Markelj, J., et al., A simplified method for evaluating building sustainability in the early design phase for architects. Sustainability, 2014. 6(12): p. 8775-8795. [CrossRef]

- Macmillan, S., et al., Mapping the design process during the conceptual phase of building projects. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 2002. 9(3): p. 174-180.

- Conejos, S., C. Langston, and J. Smith, AdaptSTAR model: A climate-friendly strategy to promote built environment sustainability. Habitat international, 2013. 37: p. 95-103. [CrossRef]

- De Paris, S., C.N. Lacerda Lopes, and A. Neuenfeldt Junior, The use of an analytic hierarchy process to evaluate the flexibility and adaptability in architecture. Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research, 2022. 16(1): p. 26-45. [CrossRef]

- Leising, E., J. Quist, and N. Bocken, Circular Economy in the building sector: Three cases and a collaboration tool. Journal of Cleaner production, 2018. 176: p. 976-989. [CrossRef]

- Battisti, A., S.G.L. Persiani, and M. Crespi, Review and Mapping of Parameters for the Early Stage Design of Adaptive Building Technologies through Life Cycle Assessment Tools. Energies, 2019. 12(9): p. 1729. [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, B.R., S. Mousazadeh, and G. Safarzadeh, Agility, adaptability+ appropriateness: Conceiving, Crafting & constructing an architecture of the 21st century. Enquiry The ARCC Journal for Architectural Research, 2012. 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, L.F., et al., Life cycle assessment (LCA) and life cycle energy analysis (LCEA) of buildings and the building sector: A review. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews, 2014. 29: p. 394-416. [CrossRef]

- Gharehbaghi, K., F. Rahmani, and D. Paterno. Adaptability of materials in green buildings: Australian case studies and review. in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 2020. IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Ying, W., Research on the Adaptability of Building Materials Application in Exterior Exterior Design of Buildings. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2018. 189(3): p. 032009. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L., M. Shan, and Z. Xu, Critical review of building handover-related research in construction and facility management journals. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 2021. 28(1): p. 154-173. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Walker, B. and D. Walker. Collaborative project procurement arrangements. 2015. Project Management Institute.

- Pushkar, S., R. Becker, and A. Katz, A methodology for design of environmentally optimal buildings by variable grouping. Building and Environment, 2005. 40(8): p. 1126-1139. [CrossRef]

- Black, A.K., B.E. Ross, and Z. Rockow. Identifying physical features that facilitate and impede building adaptation. in Sustainability in Energy and Buildings 2018: Proceedings of the 10th International Conference in Sustainability on Energy and Buildings (SEB’18) 10. 2019. Springer.

- Forbes, L.H. and S.M. Ahmed, Modern construction: lean project delivery and integrated practices. 2010: CRC press.

- Reed, B., The integrative design guide to green building: Redefining the practice of sustainability. Vol. 43. 2009: John Wiley & Sons.

- Pinto, J. and J. Prescott, Variations in Critical Success Factors Over the Stages in the Project Life Cycle. Journal of Management - J MANAGE, 1988. 14: p. 5-18. [CrossRef]

- Segara, S., et al., Taxonomy of circularity indicators for the built environment: Integrating circularity through the Royal Institute of British architects (RIBA) plan of work. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2024. 446: p. 141429. [CrossRef]

- Long, P.W., Architectural Design for Adaptability and Disassembly. Publication Date: 2014 Publication Name: Creating_Making, 2014. 10.

- Carthey, J., et al., Flexibility: Beyond the Buzzword—Practical findings from a systematic literature beview. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 2011. 4(4): p. 89-108. [CrossRef]

- Thai, H.-T., T. Ngo, and B. Uy. A review on modular construction for high-rise buildings. in Structures. 2020. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.W. and M.M. Kumaraswamy, An evaluation of construction time performance in the building industry. Building and Environment, 1996. 31(6): p. 569-578. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).