1. Introduction

Proper nutrition is a cornerstone of animal welfare and longevity, fundamentally influencing the qualitative parameters of their lives. An optimal diet for animals must provide a balanced array of essential nutrients to satisfy their physiological needs. When these nutritional requirements are not met, various disorders can emerge, significantly compromising the animal’s health and overall quality of life [

1].

Obesity, among the most prevalent nutritional disorders in veterinary practice, presents a profound challenge due to its widespread occurrence and detrimental impact on animal health. Characterized by an excessive accumulation of adipose tissue, obesity disrupts normal physiological functions and predisposes animals to a myriad of comorbidities, including respiratory, articular, and locomotor disorders [

2,

3]. The prevention, early detection, and management of obesity are critical to ensuring the health and well-being of companion animals.

The etiology of obesity in dogs is multifactorial, encompassing genetic predispositions, breed-specific traits, age, physical inactivity, caloric intake, feeding practices, hormonal imbalances, medication use, and factors related to the owner and environment [

3,

4,

5]. A thorough understanding of these contributory factors and their interactions is vital for developing and implementing effective strategies to mitigate obesity in canines.

Early and accurate diagnosis is paramount in managing obesity and averting its adverse consequences. A variety of diagnostic tools and methodologies are available for this purpose, including the Canine Body Mass Index (CBMI), Relative Body Weight (RBW), body fat percentage estimation (%BF), and Body Condition Score (BCS), alongside direct inspection and palpation techniques [

3]. Each method provides valuable insights into the animal’s body condition and informs tailored intervention strategies.

This review endeavors to compile a comprehensive synthesis of current knowledge on canine obesity, delineating its predisposing factors and the most effective methods for assessing body condition. By doing so, it aims to furnish veterinary professionals and researchers with an invaluable resource for advancing the understanding and management of obesity in dogs. Enhanced insight into this critical issue will foster better preventive and therapeutic approaches, ultimately improving the health and longevity of canine companions.

2. Canine Obesity

Conceptually, obesity is defined as a nutritional disorder characterized by the accumulation of fat beyond what is necessary for normal bodily functions, representing a multifactorial pathological condition that adversely affects animal health and well-being [

6]. In dogs, obesity is diagnosed when fat accumulation exceeds the ideal by 15 to 20% [

7], affecting between 20 to 40% of the canine population [

8]. This prevalence underscores that obesity is not only a human health concern but also a significant issue in veterinary and zootechnical contexts.

According to Miyai et al. (2021) [

9], canine obesity can be classified into two types: hypertrophic and hyperplastic. Hypertrophic obesity (simple obesity) is characterized by an increase in the size of adipocytes within adipose tissue. In contrast, hyperplastic obesity involves an increase in the number of adipocytes. The authors also note that as dogs age, the number of adipocytes naturally increases, indicating that age is a key factor influencing canine obesity.

Adipocytes, specialized cells that store lipids, are present in greater numbers in overweight and obese animals. Marques et al. (2020) [

10] describe obesity as a low-grade chronic inflammation due to high levels of cytokines and pro-inflammatory proteins secreted by adipocytes in overweight animals. Mendes et al. (2013) [

11] distinguish between hypertrophic obesity, which involves hyperstimulation of adipose tissue due to excess body fat typically seen in adults, and hyperplastic obesity, predominantly caused by excessive caloric intake during the growth phase in young animals.

Obesity in dogs and cats is associated with a spectrum of health disorders, paralleling those observed in humans. Overweight animals are at increased risk for several conditions, including dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease [

12], and orthopedic disorders [

13]. [

14] and [

9] highlight that the most affected systems in obese dogs include the locomotor, respiratory, cardiovascular, endocrine, immune, and integumentary systems. Locomotor problems in obese dogs can result in joint dysfunction, increased susceptibility to fractures, arthritis, ligament ruptures, and exacerbated pain during lameness [

15,

16].

Endocrine disorders associated with obesity include diabetes mellitus, which can result from the pancreas’s inability to secrete insulin (type 1) or the body’s failure to use insulin effectively (type 2), which can occur through various mechanisms [

14,

17]. Cardiovascular and respiratory alterations due to fat accumulation can affect heart rhythm and increase ventricular volume as the heart works harder [

14]. Tôrres (2009) [

18] identifies respiratory diseases exacerbated by obesity, such as tracheal collapse, laryngeal paralysis, and brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome.

Miyai et al. (2021) [

9] also note the association between obesity and an increased incidence of neoplastic diseases, particularly mammary tumors in adult female dogs. Additionally, they report that excess weight significantly impacts reproductive health by reducing testosterone levels and sperm quality in males and increasing infertility in females.

Obesity leads to elevated triglycerides and cholesterol levels, with notable alterations in lipoprotein profiles [

19]. This metabolic derangement is often accompanied by chronic low-grade inflammation, driven by pro-inflammatory adipokines and cytokines secreted by adipocytes [

20]. Furthermore, oxidative stress, exacerbated by excessive body fat, contributes to the development of various chronic diseases, including cancer, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular conditions [

21]. Obese dogs are particularly prone to congestive heart failure and hypertension, with structural cardiac changes observed within as little as nine weeks of weight gain [

22]. Additionally, orthopedic problems, such as traumatic and degenerative disorders, are more prevalent in severely obese dogs, with osteoarthritis emerging at a significantly younger age in those with higher body condition scores [

23].

These examples highlight the multifaceted nature of obesity and its wide-ranging impacts on canine health. However, they do not encompass the entirety of pathological effects documented in the literature concerning obesity in dogs. This review seeks to provide a comprehensive overview of the current understanding of canine obesity, its contributing factors, and the health complications it entails, thereby informing more effective prevention and treatment strategies in veterinary practice.

3. Factors for Obesity

Obesity is a multifactorial syndrome influenced by genetic, breed-specific, age-related, social, cultural, metabolic, and environmental factors, among others [

3,

6,

9]. Due to the extensive scope of information on this subject, we focus on the most discussed factors in literature.

Dietary habits and factors are highlighted by Aptekmann et al. (2014) and Miyai et al. (2021) [

4,

9]. The genesis of canine obesity, culturally influenced by humans, is linked to the unregulated provision of treats and snacks, high-calorie foods in large quantities and high frequency (number of meals), and table scraps offered by pet owners.

It is important to note that energy requirements naturally vary between breeds, and this must be considered since breed type is a predisposing factor for obesity [

24] exemplify that certain breeds, such as Golden Retrievers, Labrador Retrievers, Cocker Spaniels, Beagles, and Collies, tend to obesity more frequently. Conversely, Guimarães and Tudury. (2006) [

25] cite German Shepherds, Great Danes, Boxers, and Fox Terriers as less susceptible to obesity.

Age and neutering are significant factors in the occurrence of obesity. Excess weight appears to be particularly problematic in middle-aged dogs and cats. Carciofi. (2005) [

26] reports that the prevalence of obesity occurs between 5 and 10 years of age, explained by the natural reduction in energy expenditure due to decreased physical activity and metabolic changes. Oliveira et al. (2010) [

27] state that neutering exacerbates obesity due to reduced metabolic rates, primarily due to hormonal changes post-neutering, with females having a higher prevalence of obesity [

14].

The lifestyle of animals, influenced by the conditions provided by their owners, also plays a crucial role. According to Rodrigues. (2008) [

28], obesity is prevalent in animals living in apartments or houses without yards due to the lack of adequate exercise, as observed in free-living dogs.

Certain endocrine diseases are reported as causes of canine obesity, such as hypothyroidism and hyperadrenocorticism. Bach et al. (2007) [

2] explains that hypothyroidism reduces metabolic rates, leading to lethargy, weakness, cold intolerance, exercise intolerance, prostration, weight gain, and consequently obesity. In hyperadrenocorticism, the animal exhibits polyphagia, resulting in weight gain and potential obesity.

4. Body Condition

4.1. Body Condition Assessment in Dogs

The study of canine body condition dates back to the 1960s, with one of the earliest studies conducted in Sweden by Krook et al. (1960) [30], who classified dogs as obese based on macroscopic observations of fat accumulation. In the 1970s, Mason [31] determined through palpation and visual assessment that 28.0% of 1000 evaluated dogs were overweight and/or obese. Edney and Smith (1986) [

23] later observed that 21.4% of a population of 8,268 dogs were obese, using a 5-point Body Condition Score (BCS).

In 1997, Laflamme [41] developed a method for assessing body condition in dogs based on inspection and palpation, with a body condition score ranging from 1 to 9, which remains one of the most widely used methods today.

Various methods for evaluating body composition and condition currently exist, including dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), magnetic resonance imaging, neutron activation analysis, bioelectrical impedance, ultrasonography, hydrodensitometry, computed tomography, body mass indices, and anthropometry. Lower-cost methods are now being integrated into routine veterinary practice [

28].

Recognizing overweight and undernutrition in dogs is generally straightforward; however, precise diagnosis requires accurate quantification methods [32]. Thus, there is a need for a reliable, cost-effective, rapid, and accurate method to determine the exact amount of body mass an animal needs to lose or gain during rehabilitation [33]. The following section describes the primary methods currently used for assessing canine body condition.

4.2. Body Weight and Relative Body Weight

Weighing is the most commonly used measure to estimate body condition and nutritional status in small animal clinics [

9]. It is a dynamic factor subject to physiological changes [

25].

To identify weight gain, the current weight should be compared to previous weights recorded in medical records. Keeping weight records on vaccination cards is crucial, as these provide veterinarians with data to inform prescriptions [34]. For purebred dogs, weights can be compared to breed standards, and the ideal body weight for the animal can be calculated [35].

Relative Body Weight (RBW) represents the ratio between the animal’s current weight and its calculated optimal weight. An RBW of less than 1 indicates underweight, an RBW of 1 or 100% indicates optimal weight, and an RBW greater than 1 indicates overweight. However, this method’s accuracy is challenging due to the vast diversity in weight and body size among dog breeds [

15].

Table 1.

Standard Weight of Various Dog Breeds.

Table 1.

Standard Weight of Various Dog Breeds.

| Breed |

Males (Kg) |

Females (Kg) |

| Basset Hound |

29-34 |

22-29 |

| Beagle |

6-10 |

6-9 |

| Boxer |

25-32 |

22-27 |

| Chihuahua |

0.9-2.7 |

0.9-2.7 |

| Chow Chow |

20-22 |

18-22 |

| Cocker Spaniel |

11-13 |

9-11 |

| Collie |

29-34 |

22-29 |

| Small Dachshund |

3.6-4.5 |

3.6-4.5 |

| Standard Dachshund |

7-10 |

7-10 |

| Dalmatian |

22-29 |

20-25 |

| Doberman |

29-36 |

25-31 |

| Golden Retriever |

29-34 |

25-29 |

| Siberian Husky |

20-27 |

16-22 |

| Labrador Retriever |

29-36 |

25-31 |

| Maltese |

1.8-2.7 |

1.9-2.7 |

| Standard Poodle |

22-27 |

20-25 |

| Toy Poodle |

3.1-4.5 |

3.1-4.5 |

| Rottweiler |

36-43 |

31-38 |

| Miniature Schnauzer |

7-8 |

5-7 |

| German Shepherd |

34-40 |

31-38 |

| Shetland Sheepdog |

7-10 |

6-8 |

| Shih Tzu |

5.4-8 |

4.5-7 |

| Yorkshire Terrier |

1.8-3.1 |

1.3-2.7 |

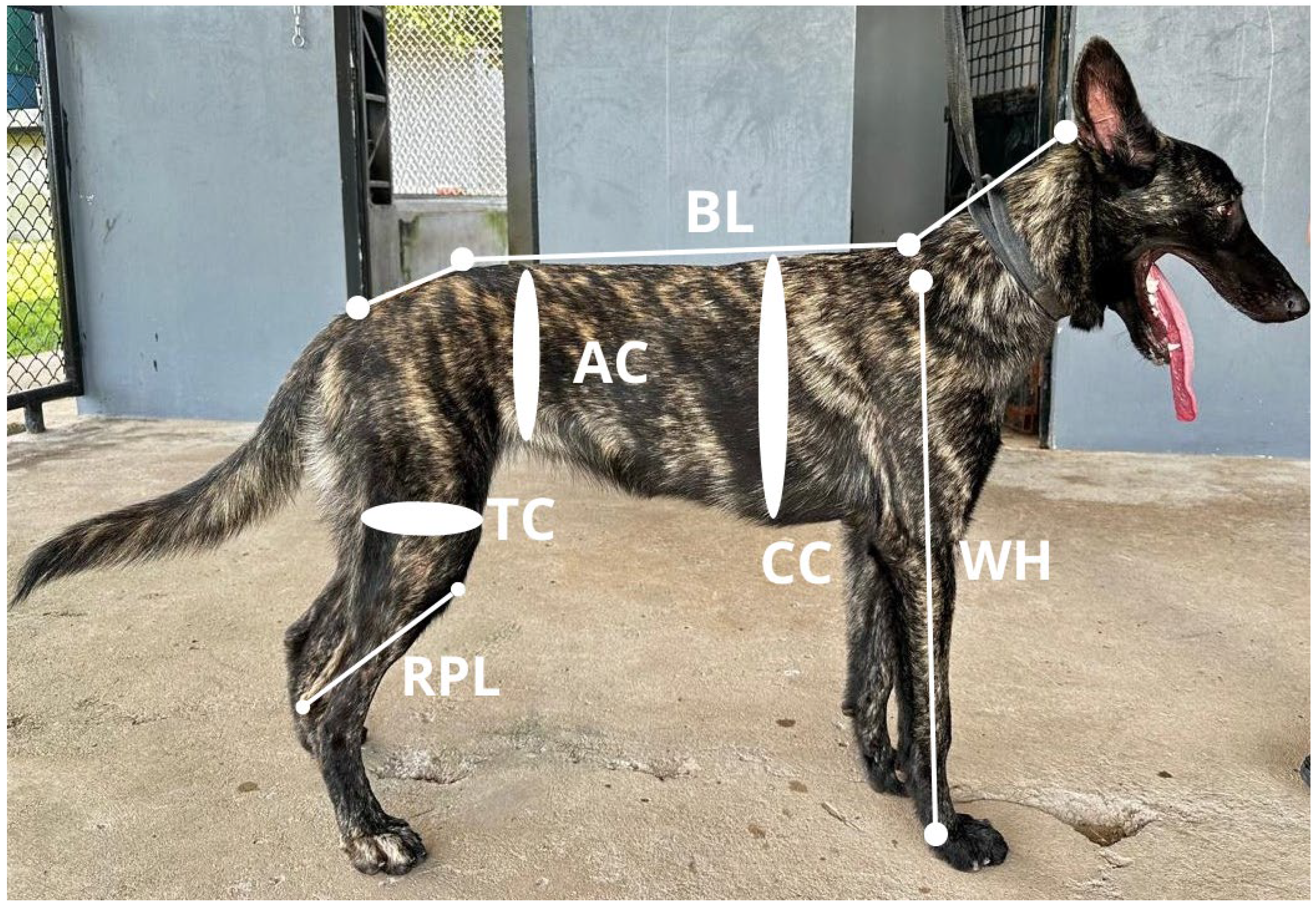

4.3. Morphometry

Morphometry evaluates body measurements at various sites, based on the premise that basic body proportions relate to the total lean tissue, and any increase in measurements can be explained by fat addition [36,37]. This technique involves combining length measurements, such as head, thorax, and limb lengths, with the animal’s circumference measurements. Equations are then generated to yield a percentage result. The primary limitation of this method is the precision of the dog’s measurements for accurate calculation. Before diagnosing conditions, it is recommended to assess for clinical signs of endocrine disorders and perform complementary tests as necessary [37].

While morphometric measurements are routinely used in humans, there are few studies on their application in dogs [38]. Establishing which body measurements significantly change with weight gain or loss is crucial, as these measurements can be performed by the owner. This allows owners to monitor the effectiveness of obesity treatment protocols, which is essential for successful outcomes [39].

Carciofi (2005) [

26] highlights that weight gain or loss directly reflects abdominal circumference measurements, while thoracic circumference measurements are less affected in dogs. They assert that up to three measurements are necessary to estimate body conformation accurately. In his study, Guimarães (2009) [39] considered six anatomical sites for body measurements in animals (

Table 2): withers height (WH), body length (BL), right pelvic limb length (RPL), abdominal circumference (AC), thoracic circumference (TC), and thigh circumference (TC).

The importance of thigh circumference is underscored by recent findings, which suggest that this measurement is a reliable indicator of muscle mass and can provide valuable insights into the physical condition of the animal [40]. Therefore, relying solely on Body Condition Score (BCS) is not sufficient for a comprehensive assessment, as it does not capture variations in muscle mass and body fat distribution as effectively as morphometric measurements [40].

Figure 1.

Anatomical Sites - Morphometric Measurements in Dogs.

Figure 1.

Anatomical Sites - Morphometric Measurements in Dogs.

According to Burkholder (2000) [

7], morphometric measurements can establish the percentage of body fat (%BF) using the following equation: %BF = (-1.7 x RPL_cm) + (0.93 x AC_cm) + 5. Research on body composition in dogs and cats reveals that animals classified as being in optimal body condition possess a body fat percentage between 15% and 20% [41,42].

4.4. Body Mass Index (BMI)

Body Mass Index (BMI) is a critical index that relates weight to height and can be correlated with mortality due to either obesity or malnutrition [43]. Initially used as a tool to evaluate human body weight, Muller et al. (2008) [32] adapted BMI for use in dogs, naming it Canine Body Mass Index (CBMI). They concluded that the measurement of the spine combined with the length of the pelvic limb is a viable parameter to replace height used in humans. CBMI also serves as a parameter for evaluating the development of controlled physical activities for dogs.

This widely used method is calculated using an equation based on the individual’s height and weight: BMI = W(kg)/(WH)^2. Two physical measurements are taken with the animal standing, limbs perpendicular to the ground, and the head in an upright position. Values between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m² indicate a normal individual. Overweight animals have values between 25.0 and 29.9 kg/m², while obese individuals present values ≥ 30 kg/m² [44].

It is important to note that CBMI does not distinguish between lean and fat mass. Thus, animals with significant muscle mass may have altered CBMI without being obese. This method should be applied to animals that do not have substantial muscle mass, such as breeds like the Pit Bull, known for their muscular build [45]. Despite operational difficulties, its use is recommended in conjunction with direct body composition measures [43].

4.5. Body Condition Score (BCS)

BCS is the most commonly used and easily applicable method in clinical practice today. It involves inspecting and palpating fat in areas such as the ribs, abdomen, neck, tail, and regions of bony prominences where fat accumulates [37,41]. The BCS scale ranges from 1 to 9, where values between 1 and 3 indicate underweight, 4 and 5 indicate ideal condition, 6 and 7 indicate overweight, and 8 and 9 indicate obesity [41]. The reliability of this method was demonstrated by [46]. BCS allows for a quick and straightforward assessment of the patient’s body condition. Currently, there are two systems used in small animal clinics: the five-point system and the nine-point system, with the nine-point system being the most widely used [47]. BCS determination is performed by palpating the thoracic cage, abdomen, and tail base, assessing the thickness of the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Each score increase above the ideal corresponds to a 10-15% increase in weight, meaning a dog with a BCS of 7 is 20-30% heavier than its ideal weight [48].

An ideal body condition is suggested when the ribs are easily palpable, and the dog has an hourglass shape when viewed from above. Animals with a bulging abdomen from the last rib, evident fat deposits on either side of the tail base, above the hips, and/or in the inguinal region, with a rib cage that is not easily palpable, indicate excess weight [

24]. However, BCS alone may not provide a complete picture of an animal’s body composition, as it does not differentiate between lean muscle and fat mass. Therefore, integrating BCS with morphometric measurements is crucial for a comprehensive evaluation of body condition [40].

| Score |

Body Condition |

Body Characteristics |

| 1 |

Underfed |

Ribs, lumbar vertebrae, pelvic bones, and all bony prominences visible from a distance. No discernible body fat. Evident loss of muscle mass. |

| 2 |

Underfed |

Ribs, lumbar vertebrae, and pelvic bones easily visible. No palpable fat. Some other bony prominences may be visible. Minimal muscle mass loss. |

| 3 |

Underfed |

Ribs easily palpable with no palpable fat. Top of lumbar vertebrae visible. Pelvic bones begin to be visible. Evident waist and abdominal tuck. |

| 4 |

Ideal |

Ribs easily palpable with minimal fat coverage. Waist observed from above. Evident abdominal tuck. |

| 5 |

Ideal |

Ribs palpable without excessive fat coverage. Retracted abdomen when viewed from the side. |

| 6 |

Overfed |

Ribs palpable with slight excess fat coverage. Waist visible from above but not prominent. Apparent abdominal tuck. |

| 7 |

Overfed |

Ribs difficult to palpate; heavy fat coverage. Evident fat deposits over the lumbar area and tail base. Absent or only visible waist. Abdominal tuck may be present. |

| 8 |

Overfed |

Ribs not palpable under thick fat coverage or palpable only with significant pressure. Heavy fat deposits over the lumbar area and tail base. No waist. No abdominal tuck. Abdominal distension may be evident. |

| 9 |

Obese |

Massive fat deposits over the chest, spine, and tail base. Fat deposits on the neck and limbs. Evident abdominal distension. |

|

Adapted from Laflamme (1997) [41].

|

Recent research by Söder et al. (2024) [40] has provided new insights into the effects of exercise on canine health and body composition. Their study demonstrates that structured exercise regimens significantly improve body condition scores and reduce body fat percentage in dogs, particularly those diagnosed with obesity. The research emphasizes that consistent physical activity not only aids in weight management but also enhances overall metabolic health. Dogs participating in regular exercise exhibited improvements in both morphometric measurements and BCS, indicating a more favorable body composition and a reduction in fat accumulation.

4.6. Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA)

A precise diagnosis of canine body condition can be achieved using techniques such as deuterium isotope dilution [49] and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA). These techniques determine lean and fat mass percentages but are expensive and not commonly used in clinical practice.

DEXA was initially developed to measure mineral content but has since been adapted to measure body fat and lean tissue. It employs two different energy levels (70 and 140 kVp) to differentiate tissue types and quantities. DEXA can also establish bone mineral density, bone mineral content, fat mass, and lean mass [50]. These measurements are critical for nutritional research, understanding the pathogenesis of bone diseases, identifying factors that may affect normal musculoskeletal development, and assessing body composition in patients with metabolic, endocrine, and nutritional disorders.

To confirm the reliability of the Body Condition Score (BCS), Brunetto et al. (2011) [46] compared BCS with DEXA and deuterium oxide dilution (D²O). They found a high correlation between the two techniques’ accuracy (r² = 0.92) for evaluating body fat percentage.

Borges (2006) [38] noted that DEXA is precise in estimating body composition in adult cats, but standardization for dogs is needed. Furthermore, due to the high cost of equipment, DEXA is mainly used experimentally in small animal research.

4.7. Ultrasound (USG)

Imaging diagnostic methods can indirectly monitor fat deposit sites. Wilkinson and McEwan (1991) [51] suggested that measuring subcutaneous fat thickness between the third and fifth lumbar vertebrae using ultrasound could predict total body fat in dogs. This method is non-invasive and practical. However, obesity can impair image quality (echogenicity - darkness) due to the increased distance between the transducer and the organ MCbeing examined caused by subcutaneous and intra-abdominal fat deposits [52].

A pioneering study on canine subcutaneous fat measurement using ultrasound was conducted by Wilkinson and McEwan (1991)[51]. They considered the relationship between subcutaneous fat observed via ultrasound and histologically evaluated subcutaneous fat to determine total body fat in dogs. The study concluded that total body fat could be successfully predicted from measurements taken from the lower back and lumbar region, suggesting that ultrasound can safely and reliably measure total body fat in dogs.

However, a study by Carvalho (2015) [53] reported that BCS, morphometric measurements, and CBMI strongly correlate, indicating their reliability in assessing body condition in dogs, with consistent results among them. In contrast, ultrasound did not yield significant results as expected. Therefore, the author concluded that each animal should be individually assessed to apply the most convenient technique.

4.8. Bioimpedance (BIC)

Bioimpedance has proven useful in both humans and animals for measuring parameters such as blood flow and body composition (known as bioimpedance analysis - BIA) [54]. Bioimpedance (BIC) evaluates body composition by measuring electrical conductivity differences in tissues. Resistance (R) and reactance (Xc) measurements form the equation that determines the result [55]. BIC estimates the amounts of water and fat present and, with the help of equations, determines the percentage of lean mass (LM) [56].

4.9. Direct Inspection and Palpation

The most practical and widely used method in most cases is a simple physical examination through inspection and palpation. Dog ribs should be easily palpable. When viewed dorsally, dogs should have an hourglass shape. Loss of the central narrowing (waist), a bulging abdomen from the last rib, visible fat deposits on either side of the tail base, above the hips, and/or in the inguinal region, and a rib cage that is not easily palpable indicate obesity [23].

5. Conclusions

Canine obesity, a prevalent and multifaceted condition, poses significant challenges in veterinary practice due to its detrimental impact on animal health and quality of life. The comprehensive understanding of its etiology, encompassing genetic, breed-specific, age-related, lifestyle, dietary, hormonal, and owner-related factors, is crucial for developing effective prevention and management strategies.

Accurate and early diagnosis, facilitated by various assessment methods such as BCS, CBMI, RBW, body fat percentage estimation, and direct inspection and palpation, is vital for addressing obesity in dogs. This review underscores the importance of a holistic approach, integrating multiple assessment techniques to provide a comprehensive evaluation of body condition and inform individualized intervention plans.

Future research should focus on refining existing assessment methodologies and exploring novel approaches to enhance the accuracy and practicality of body condition evaluations. Moreover, continued efforts to educate pet owners on the significance of proper nutrition, regular physical activity, and responsible feeding practices are essential for mitigating the incidence of obesity in companion animals. By fostering a deeper understanding of canine obesity and its multifactorial nature, veterinary professionals can better safeguard the health and well-being of dogs, ultimately contributing to their longevity and quality of life.

Author Contributions

writing—original draft preparation, A.G.C.R.; writing—review and editing, G.M.F, K.M.A.S.C.M ; visualization, N.D.S.L., R.T.U., J.T.P; supervision, G.M.F., N.D.S.L., R.T.U., J.T.P.; project administration, G.M.F

Funding

This research received no external funding

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sturgess, K., Hurley, K.J. Nutrition and Welfare. In: Rochlitz, I. (eds) The Welfare Of Cats. Animal Welfare, vol 3. Springer.

- Bach, J. F.; Rozanski, E. A.; Bedenice, D.; et al. Association of expiratory airway dysfunction with marked obesity in healthy adult dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res., 2007, 68, 670–675. [CrossRef]

- Zoran, D. L. Obesity in dogs and cats: a metabolic and endocrine disorder. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract., 2010, 40, 221–239. [CrossRef]

- Aptekmann, K. P.; Suhett, W. G.; Mendes Junior, A. F.; Souza, G. B.; Tristão, A. P. P. A.; Adams, F. K.; Aoki, C. G.; Palacios Junior, R. J. G.; Carciofi, A. C.; Tinucci-Costa, M. Aspectos nutricionais e ambientais da obesidade canina. Cienc. Rural, 2014, 44, 2034-2044. [CrossRef]

- Toll, P. W.; Yamka, R. M.; Schoenherr, W. D. Obesity. In: Hand, M. S.; Thatcher, C. D.; Remillard, R. L. (Eds.). Small Anim. Clin. Nutr., 5th ed. Mark Morris Institute, 2010, pp. 501–542.

- Babilas, P. Nutritional diseases. Braun-Falco’s Dermatol., 2020, 1, 1-14.

- Burkholder, W. J.; Toll, P. W. Obesity. In: Hand, M. S. (Ed.). Small Anim. Clin. Nutr. Mark Morris Institute, 2000, pp. 401–430.

- Feitosa, M. L.; Zanini, S. F.; De Sousa, D. R.; Carraro, T. C. L.; Colnago, L. G. Fontes amiláceas como estratégia alimentar de controle da obesidade em cães. Cienc. Rural, 2015, 45, 546-551.

- Miyai, S.; Hendawy, A. O.; Sato, K. Gene expression profile of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in mild to moderate obesity in dogs. Vet. Anim. Sci., 2021, 13, 100183. [CrossRef]

- Marques, B. P.; Brunelli, S. R.; Favaro, L. S. Obesidade em cães: causas e consequências. Rev. Cient. Eletr. Cienc. Apl. FAIT, 2020, 14, 16.

- Mendes, F. F.; Rodrigues, D. F.; Prado, Y. C. L.; Araújo, E. G. Obesidade Felina. Enciclop. Biosfera, 2013, 9, 1602-1625.

- Singh, G. M.; Danaei, G.; Farzadfar, F.; Stevens, G. A.; Woodward, M.; Wormser, D. et al. Prospective Studies Collaboration (PSC). The age-specific quantitative effects of metabolic risk factors on cardiovascular diseases and diabetes: a pooled analysis. PLoS ONE, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Anandacoomarasamy, A.; Caterson, I.; Sambrook, P.; Fransen, M.; March, L. The impact of obesity on the musculoskeletal system. Int. J. Obes., 2008, 32, 211–222. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, E. K. V. Aspectos da obesidade e suas comorbidades em cães: estudo de caso. Rev. Ibero-Am. Humanid. Cienc. Educ., 2022, 8, 03. [CrossRef]

- Fazenda, M. I. N. Estudo da relação entre a obesidade e a hipertensão em cães. Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, 2010.

- Firmino, F. P. Comparacão da sintomatologia da displasia coxofemoral entre cães obesos e não-obesos. Braz. J. Dev., 2020, 6, 46840-46850.

- Ramos, J. R.; Castillo, V. Evaluation of insulin resistance in overweight and obese dogs. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Res., 2020, 6, 58-63.

- Tôrres, A. C. B. Obesidade em cães: aspectos ecodopplercardiográficos, eletrocardiográficos, radiográficos e de pressão arterial. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciência Animal), Universidade Federal de Goiás, 2009.

- Mori, N.; Lee, P.; Kondo, K.; Kido, T.; Saito, T.; Arai, T. Potential use of cholesterol lipoprotein profile to confirm obesity status in dogs. Vet. Res. Commun., 2011, 35, 223-235. [CrossRef]

- Trayhurn, P. Adipose tissue in obesity—an inflammatory issue. Endocrinology, 2005, 146, 1003–1005. [CrossRef]

- Laflamme, D. P. Companion Animals Symposium: Obesity in dogs and cats: What is wrong with being fat? J. Anim. Sci., 2012, 90, 1653-1662. [CrossRef]

- Philip-Couderc, P.; Smih, F.; Pelat, M.; Vidal, C.; Verwaerde, P.; Pathak, A.; Rouet, P. Cardiac transcriptome analysis in obesity-related hypertension. Hypertension, 2003, 41, 414-421. [CrossRef]

- Edney, A. T.; Smith, P. M. Study of obesity in dogs visiting veterinary practices in the United Kingdom. Vet. Rec., 1986, 118, 391–399. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R. W.; Couto, C. G. Medicina interna de pequenos animais. 5 ed. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier, 2015, 1474.

- Guimarães, A. L. N.; Tudury, E. A. Etiologias, consequências e tratamentos de obesidades em cães e gatos - revisão. Vet. Not., 2006, 12, 29-41.

- Carciofi, A. C. Obesidade e suas consequências metabólicas e inflamatórias em cães e gatos. Jaboticabal, 2005.

- Oliveira, M. C.; Nascimento, B. C. L.; Amaral, R. W. C. Obesidade em cães e seus efeitos em biomarcadores sanguíneos - revisão de literatura. PUBVET, 2010, 4, 795-801.

- Rodrigues, L. F. Métodos de avaliação da condição corporal em cães. Universidade Federal de Goiás. Goiânia, 2011.

- Honrado, S. A. Fatores de risco para o desenvolvimento do excesso de peso e obesidade em cães. Dissertação (Mestrado Integrado em Medicina Veterinária) - Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Lisboa, 2018.

- Krook, L.; Larsson, S.; Rooney, J. R. The effects of obesity, pyometra and diabetes mellitus on the fat and cholesterol contents of liver and spleen in the dog. Acta Physiol. Scand., 1960, 49, 29-34. [CrossRef]

- Mason, E. Obesity in pet dogs. Vet. Rec., 1970, 86, 612-616.

- Muller, D. C. M.; Schossler, J. M.; Pinheiro, M. Adaptação do índice corporal humano para cães. Cienc. Rural, 2008, 38, 134-140.

- Ferreira, S. R. A. Relação proprietário-cão domiciliado: atitude, progressividade e bem-estar. Tese (Doutorado em Medicina Veterinária), Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, 2009.

- White, G. A.; Hobson-West, P.; Cobb, K.; Craigon, J.; Hammond, R.; Millar, K. M. Canine obesity: is there a difference between veterinarian and owner perception. J. Small Anim. Pract., 2011, (online first). [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M.; et al. A current life table and causes of death for insured dogs in Japan. Prev. Vet. Med., 2015, 120, 210-218. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A. R.; Santaren, J. M.; Filho, W. J.; Meireles, E. S.; Marucci, M. F. N. Comparação da gordura corporal de mulheres idosas segundo antropometria, bioimpedância e DEXA. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr., 2001, 51, 49-55.

- Witzel, A. L.; Kirk, C. A.; Henry, G. A.; Toll, P. W.; Brejda, J. J.; Paetaurobinson, I. Use of a morphometric method and body fat index system for estimation of body composition in overweight and obese cats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc., 2014, 244, 1285-1290. [CrossRef]

- Borges, N. C. Avaliação da composição corporal e desenvolvimento de equações para a estimativa de massa gorda e massa magra em felinos (Felis catus - Linnaeus, 1775) adultos. Tese (Doutorado em Medicina Veterinária), Faculdade de Ciência Agrária e Veterinária, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Jaboticabal, 2006.

- Guimarães, P. L. S. N. Conformação corporal e bioquímica sanguínea de cadelas adultas castradas alimentadas ad libitum. Tese (Doutorado em Ciência Animal), Escola de Veterinária, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, 2009.

- Söder, J.; Roman, E.; Berndtsson, J.; Lindroth, K.; Bergh, A. Effects of a physical exercise programme on bodyweight, body condition score and chest, abdominal and thigh circumferences in dogs. BMC Vet. Res., 2024, 20, 299. [CrossRef]

- Laflamme, D. Development and validation of a body condition score system for dogs. Canine Pract., 1997, 22, 10-15.

- Laflamme, D. Development and validation of a body condition score system for cats: a clinical tool. Feline Pract., 1997, 25, 13-18.

- Mondini, L.; Monteiro, C. A. Relevância epidemiológica da desnutrição e da obesidade em distintas classes sociais: métodos de estudo e aplicação à população brasileira. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol., 1998, 1, 28-39.

- Rezende, F. A. C.; Rosado, L. E. F. P. L.; Franceschinni, S. C. C.; Rosado, G. P.; Ribeiro, R. C. L. The body mass index applicability in the body fat assessment. Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte, 2010, 16, 90-94.

- McArdle, W. D. Fisiologia do exercício: energia, nutrição e desenvolvimento humano. 5 ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan, 2003.

- Mawby, D. I.; Bartges, J. W.; D’Avignon, A. Comparison of various methods for estimating body fat in dogs. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc., 2004, 40, 109-114. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J. S.; Zimmermann, M. Principais aspectos da obesidade em cães. Rev. Cient. Med. Vet. FACIPLAC, 2016, 3, 58-63.

- Laflamme, D. P. Understanding and managing obesity in dogs and cats. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract., 2006, 36, 1283-1295. [CrossRef]

- Brunetto, M. A.; Nogueira, S.; Sá, F. C.; Vasconcellos, M. P. R. S.; Ferraudo, A. J.; Carciofi, A. C. Correspondence between obesity and hyperlipidemia in dogs. Cienc. Rural, 2011, 41, 266-271.

- Elliot, D. A. Techniques to assess body composition in dogs and cats. Waltham Focus, 2006, 16, 16-20.

- Wilkinson, M. J. A.; McEwan, N. A. Use of ultrasound in the measurement of subcutaneous fat and prediction of total body fat in dogs. J. Nutr., 1991, 121, 47-50. [CrossRef]

- Shmulewitz, A.; Teefey, S. A.; Robinson, B. S. Factors affecting image quality and diagnostic efficacy in abdominal sonography: a prospective study of 140 patients. J. Clin. Ultrasound, 1993, 21, 623-630. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L. A. R. Estudo comparativo entre quatro métodos de aferição de condição corporal em cães. Dissertação (Mestrado em Medicina Veterinária) Universidade Federal de Lavras. 69 folhas, Lavras, 2015.

- Batra, P.; Singh, S.; Pratap Singh, S. A new method for measurement of bioelectrical impedance. Int. Conf. Commun. Syst. Netw. Technol., 2011, 35, 740-743.

- Cintra, T. C. F.; Canola, J. C.; Borges, N. C.; Carciofi, A. C.; Vasconcelos, R. S.; Zanatta, R. Influência de diferentes tipos de eletrodos sobre os valores da bioimpedância corporal e na estimativa de massa magra (MM) em gatos adultos. Rev. Cienc. Anim. Bras., 2010, 11, 149-155. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S. S.; Chumlea, W. C.; Cockram, D. B. Use of statistical methods to estimate body composition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 1996, 64, 428S-435S. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).