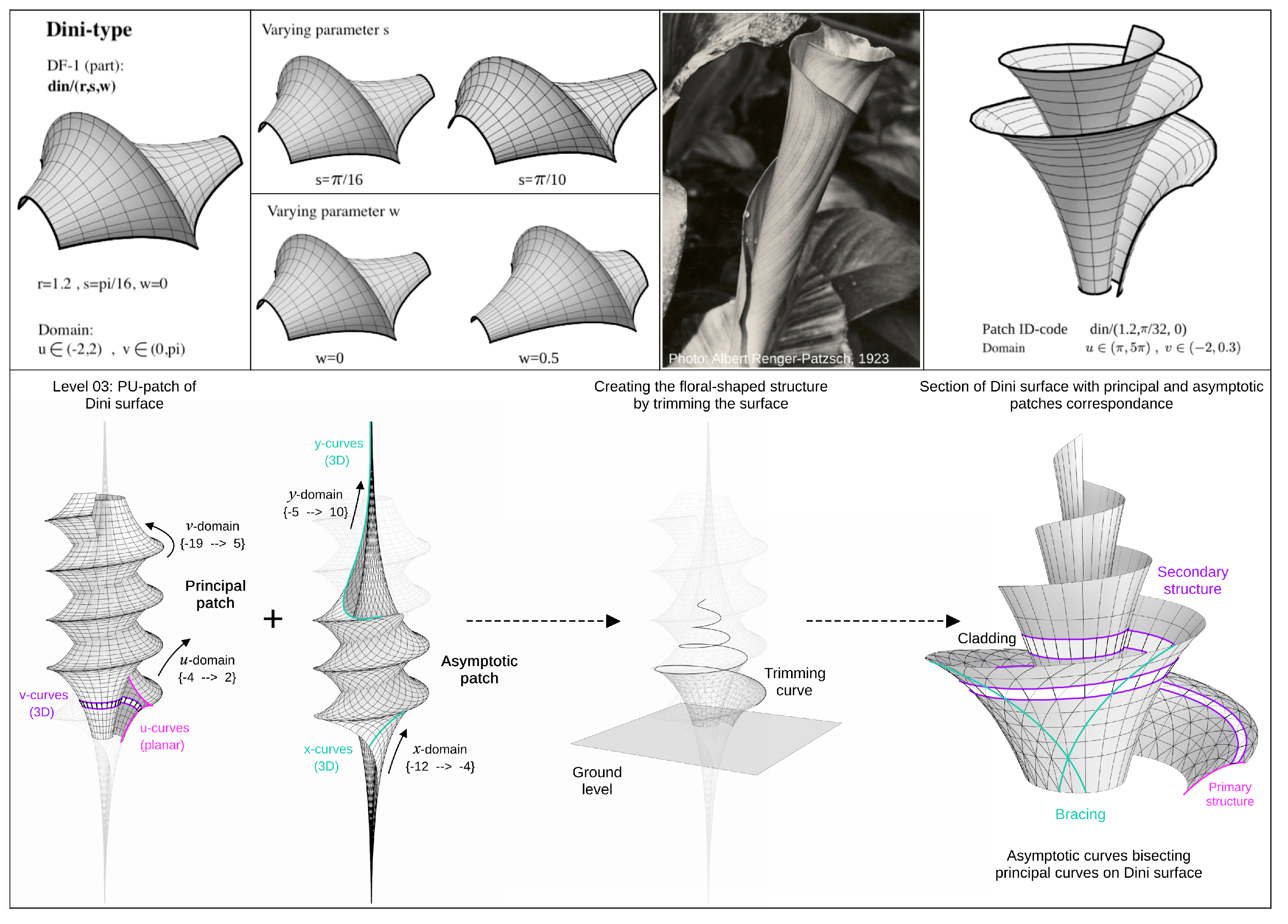

3.1. Fabrication of Structural Components

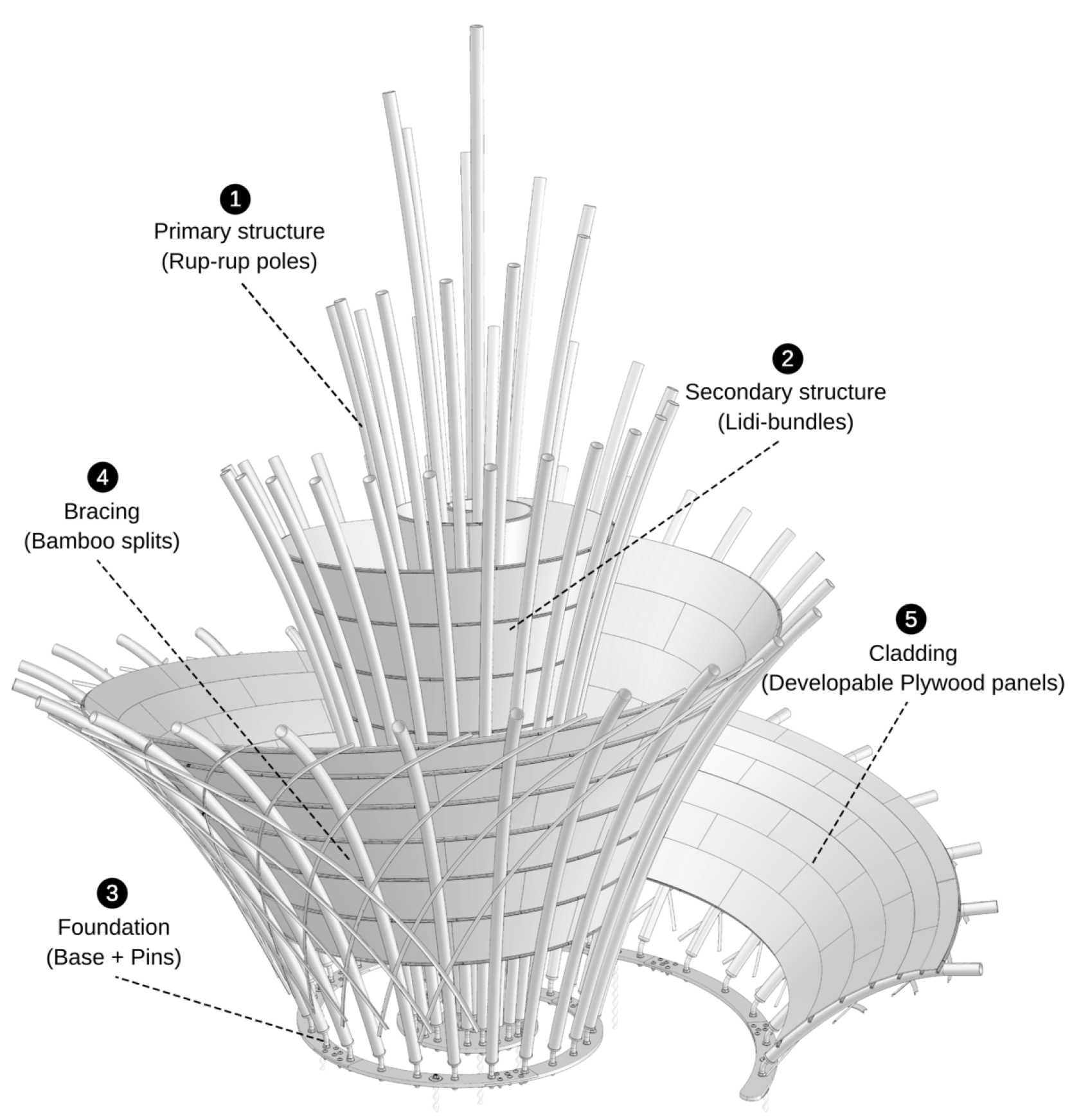

The bamboo structure comprises five structural components, as illustrated in

Figure 3. These components were fabricated using traditional techniques, which were parameterized and/or reinterpreted to simplify the fabrication process while optimizing precision and fabrication time, as explained in detail in the following Sections.

• Component 1: Primary structure → Rup-rup poles The traditional

Rup-rup technique involves making V-shaped cuts (spanning

of the pole’s width) at specific intervals along its length (in the internodes) [

3,

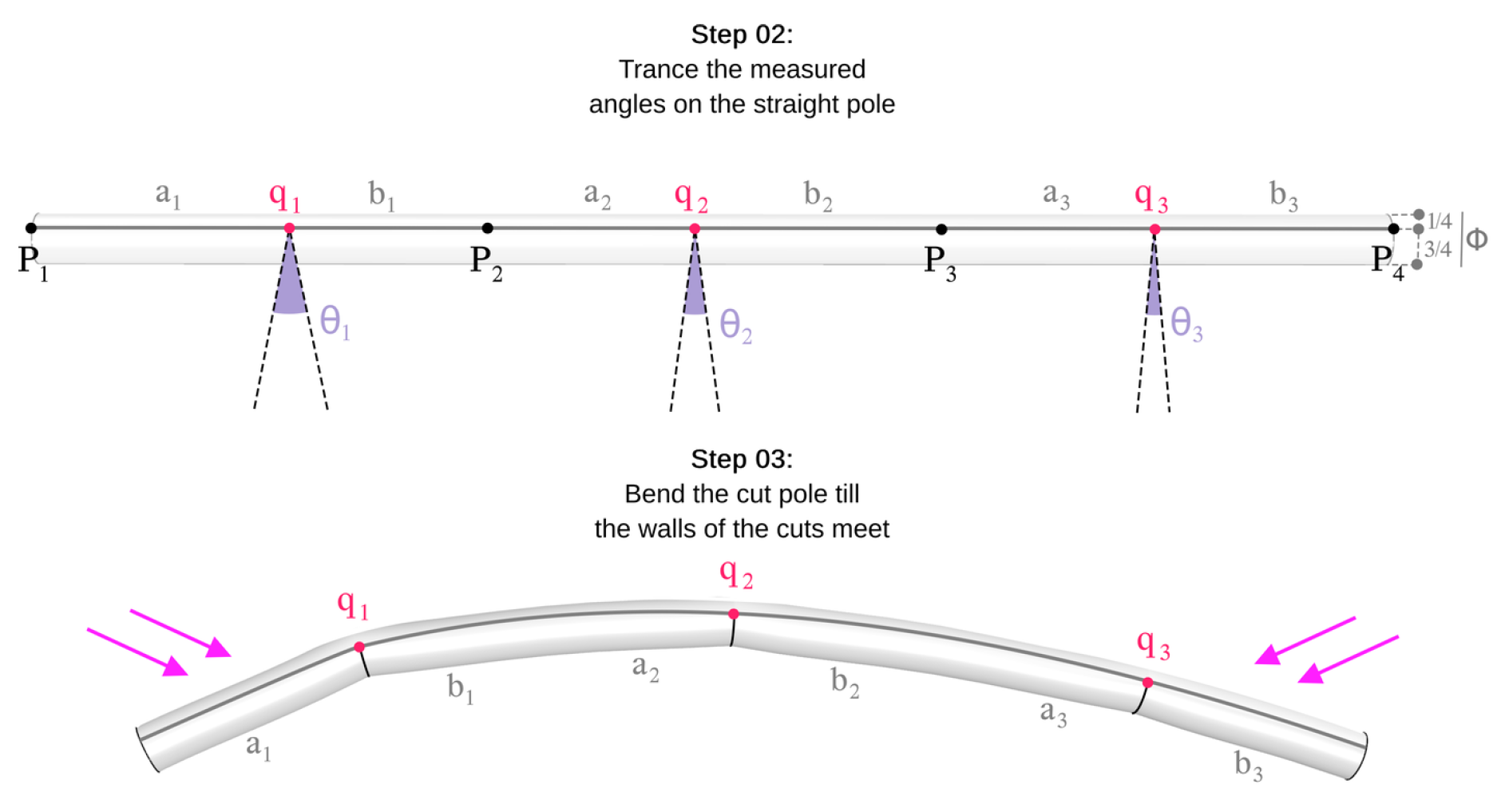

10]. The resulting pole will follow the desired curvature once pressure is applied to its extremities until the sides of each cut meet. To note that although increasing the number of cuts will better approximate the curved pole to the target network curve, it also increases the pole’s structural fragility. While this technique exists, using it to transform a straight bamboo pole into one that corresponds precisely to a desired curve is more challenging. This is because accurately determining the positions and angles of the cuts requires a mathematical reformulation of the problem. This reformulation involves inferring global properties (the overall curved shape of the bent bamboo pole) from local properties, such as changes in curvature and torsion at specific points. The mathematical reformulation of this technique varies depending on the nature of the network curve. In the following Section, we demonstrate how this is achieved planar curves (used in the realization of the structure).

The problem in 2-dimensions is relatively simpler since the planar curve

C contains no torsion. It then follows that the shape of the curve

C is determined by how it curves in the plane, as explained below. Let

be a list of discrete points on the planar curve, with

the length of the piece of curve

. Next, let

be the tangent vectors at the points

, with

the angle between

, also known as the turning angle, as shown in

Figure 4 (right). We will also refer to the turning angle

as the (average) curvature angle, since the actual (signed) curvature

of

C at

is:

Now, to carry out the (local) geometric method of bending the straight pole, we need to collect two further lists of lengths:

and

. These are the lengths of the segments between points

and points

, where each point

is obtained by intersecting the line

with the line

, as seen in

Figure 4.

Next, observe that the length of the straight pole before bending should be equal to the sum of the lengths of

and

, not the arc length of the planar curve

C. Of course, these two lengths will converge as we add more and more discrete points.

In view of the above, we are now able to start with a straight bamboo pole and bend it into the desired shape using only local knowledge at the points. This local geometric bending method is as follows: we start by collecting the data list:

Next, we mark the appropriate lengths

and

on the straight bamboo pole, and finally use the angles

to create V-shaped cuts in the pole. By simply bending the pole to close these cuts, we obtain the desired curved shape, as shown in

Figure 5.

While the cut bamboo pole traces the planar network curve up to a certain approximation, it doesn’t remain in its bent shape due to elastic properties. Various methods to address this issue have been demonstrated [

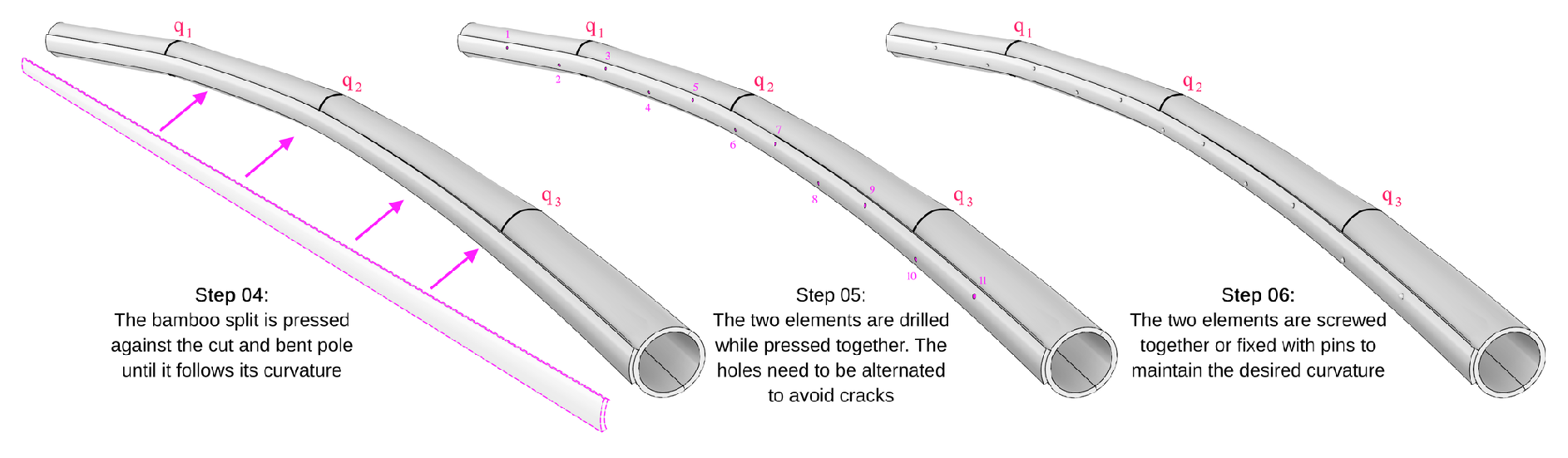

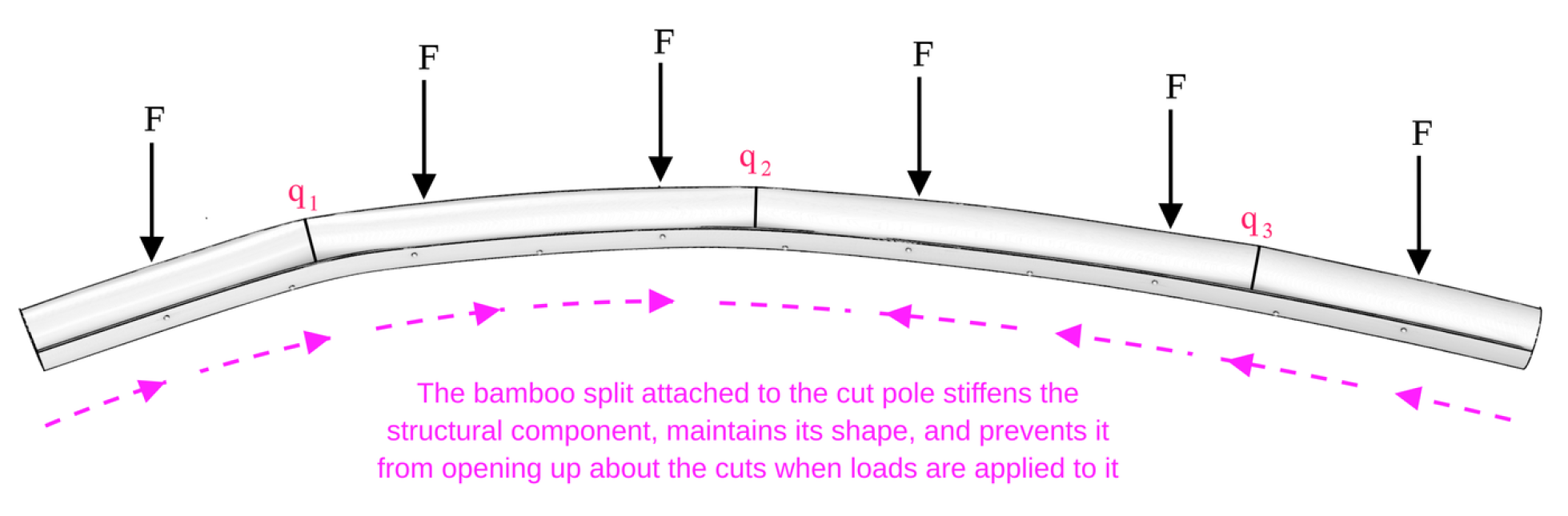

3], such as bundling several poles together to enhance structural stability through reciprocal support at the v-cut spots. However, due to project constraints, including the weight of each individual structural components, our chosen method involves screwing a longitudinal bamboo split (a segment of the pole) to the bent pole along the side with the cuts, as illustrated in

Figure 6.

It is important to mention that the choice of the positions (not only the number) of the discrete points (V-shaped cuts)

plays a crucial role in approximating the curve

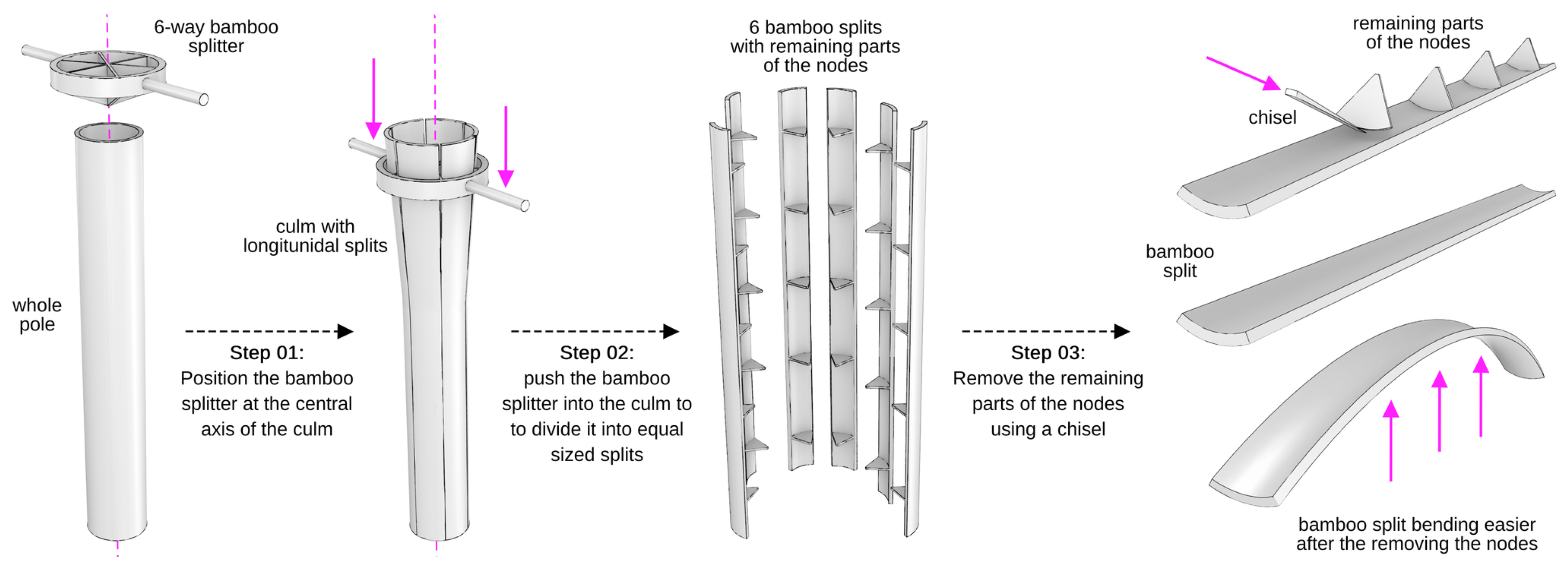

C with segments. Even with the same number of points, placing them closer together in high curvature zones than in low curvature zones allows for a better approximation. Thus, using a non-uniform distribution of points helps achieve a more accurate result with the same number of points, while also avoiding further weakening of the cut bamboo pole. In

Figure 7, we illustrate the technique used to extract longitudinal splits (as shown in

Figure 6) from the whole bamboo pole [

4]. This technique begins with using a bamboo splitter to divide the entire pole into equally sized segments. Subsequently, any remaining parts of the nodes attached to these splits are removed using a chisel to achieve a flush inner wall. This step is crucial as it facilitates easier bending and fitting of the splits over another pole. Attaching the split to the cut pole serves two purposes: it maintains the bent shape of the pole and adds structural stiffness by compensating for some of the lost material. Additionally, it introduces a layer of continuous longitudinal fibers that provide tension resistance when loads are applied to the component, as illustrated in

Figure 8.

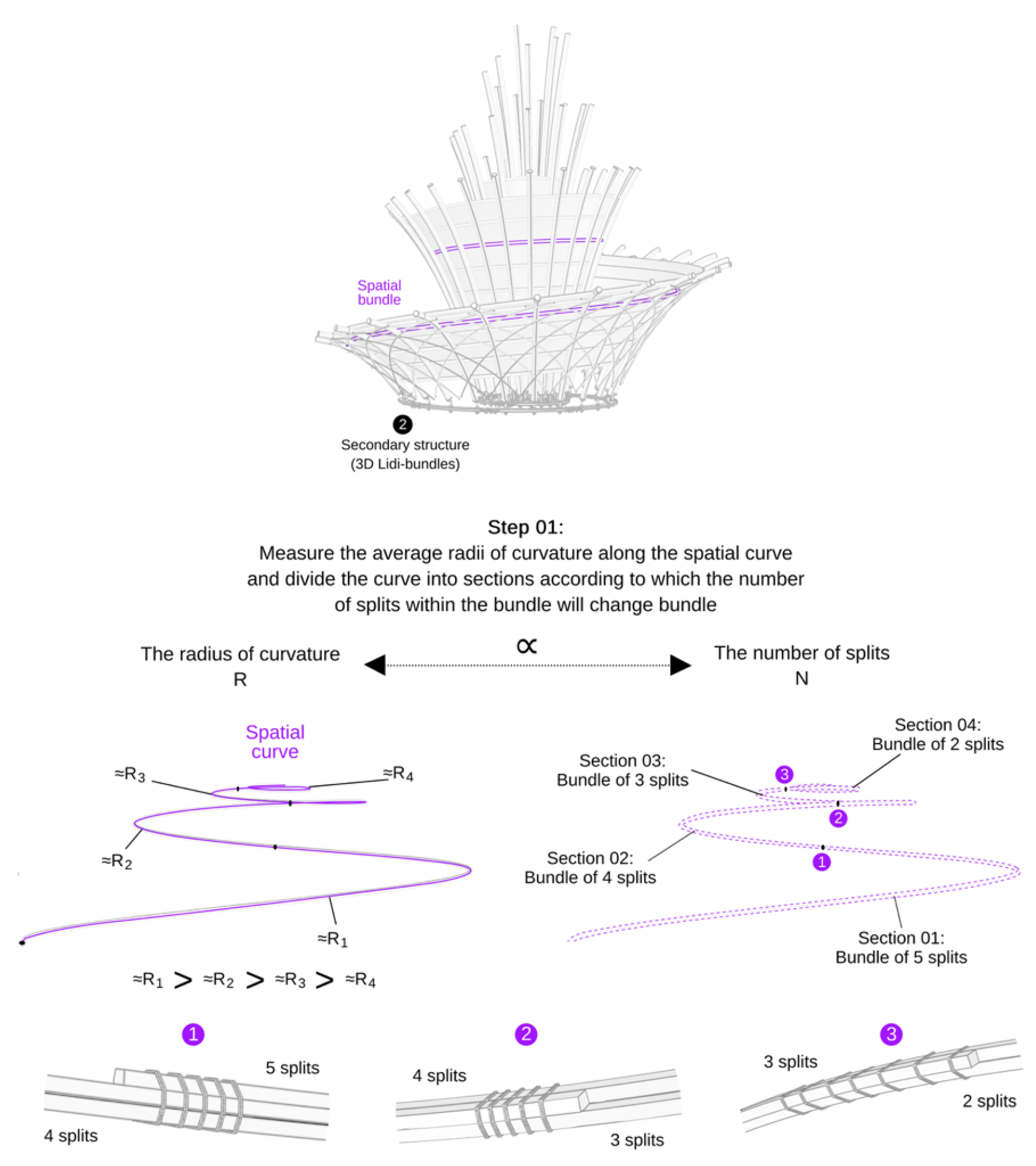

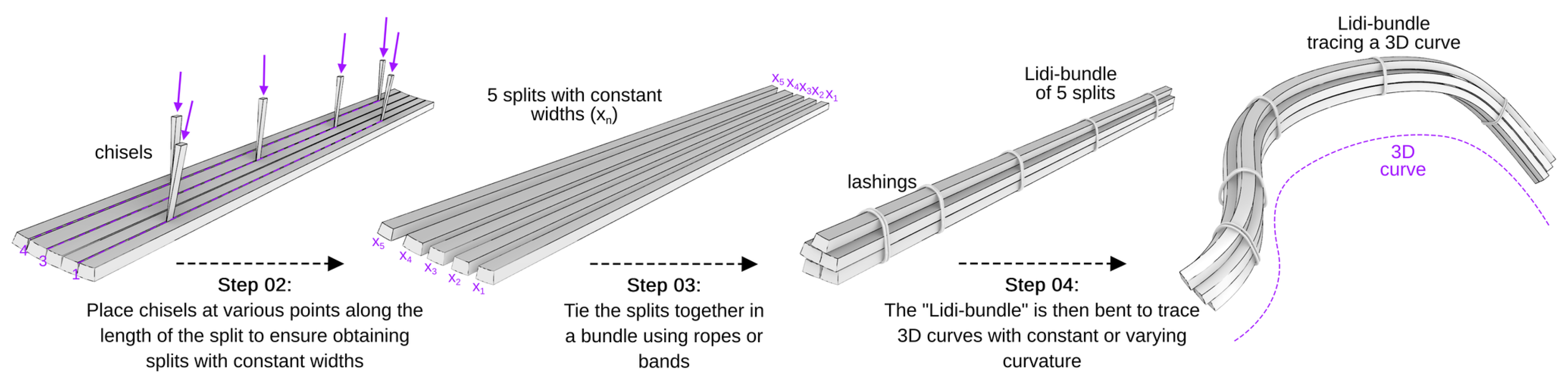

• Component 2: Secondary structure → Lidi-bundles The second component is the secondary structure made out of

Lidi-bundles. A

Lidi-bundles, as described in [

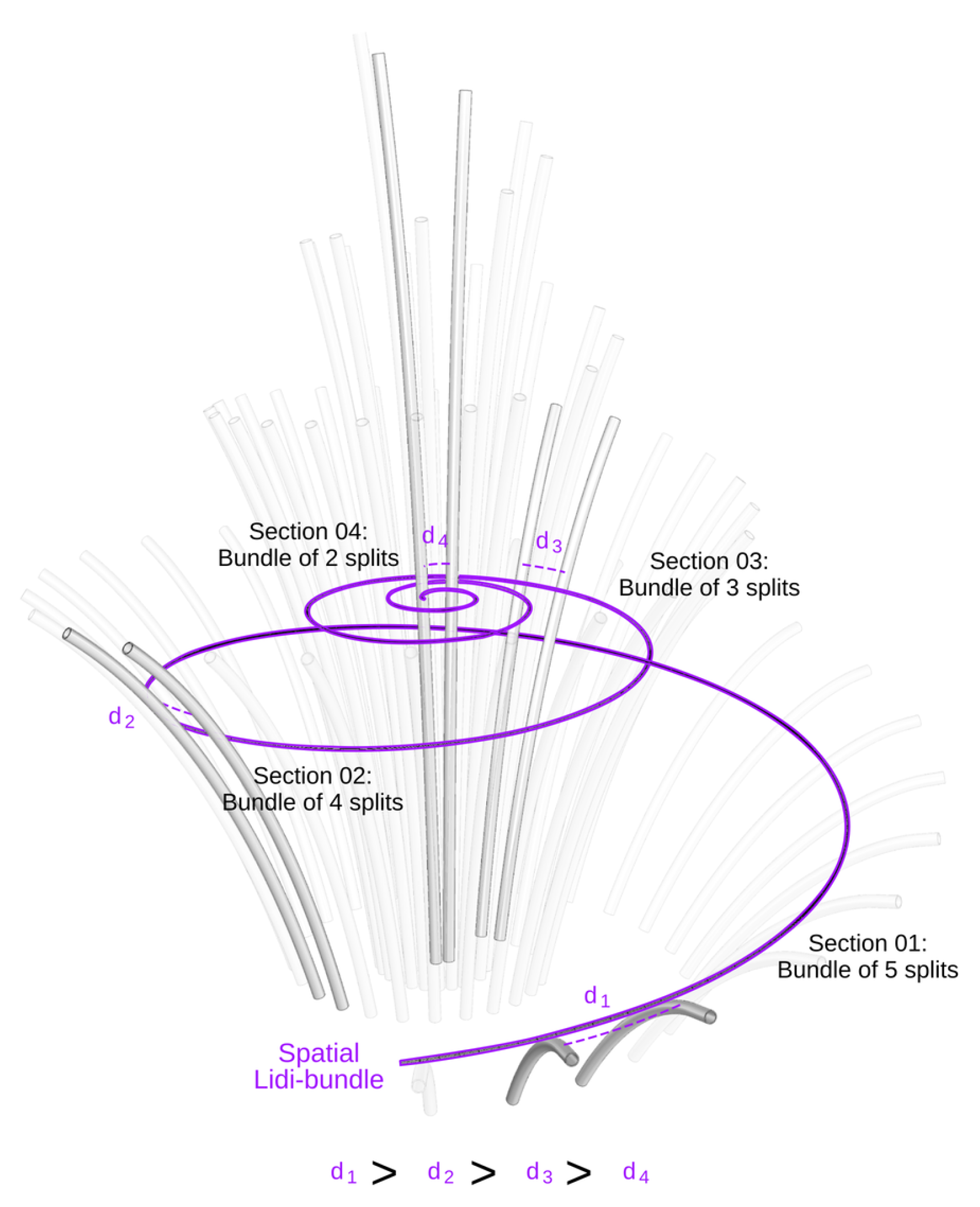

10], consists of "thin" longitudinal bamboo splits lashed together along their lengths. As depicted in

Figure 9, the number of splits in a

Lidi-bundles is directly proportional to the radii of curvature at discrete points along the spatial curve. Consequently, the spatial curve is segmented into sections where the number of splits in each bundle corresponds to the bending capacity required for the average radius of curvature in that section.

It’s important to note that while there is a logical relationship between the radius of curvature and the number of splits, the exact values are empirical and depend on factors such as the bamboo species, treatment methods, the width of the splits, etc. As seen earlier in

Figure 7, curved bamboo splits can be obtained from a pole using a bamboo splitter. However, there is a limit to how thin these splits can be made using this technique. To achieve bamboo splits with smaller widths, as shown in

Figure 10, we employ a method where the curved splits obtained from the splitter are further divided into thinner ones with nearly square cross-sections. This is done using chisels inserted at various points along the length of the split to ensure the resulting "thin" splits have a consistent width throughout their length. Subsequently, these "thin" splits are joined together and lashed to create a bundle. The bundle is manually bent to follow the spatial curve, and additional lashings are added to secure the bundle in its curved shape. As seen in the

Rup-rup case, there are structural considerations to take into account when designing the

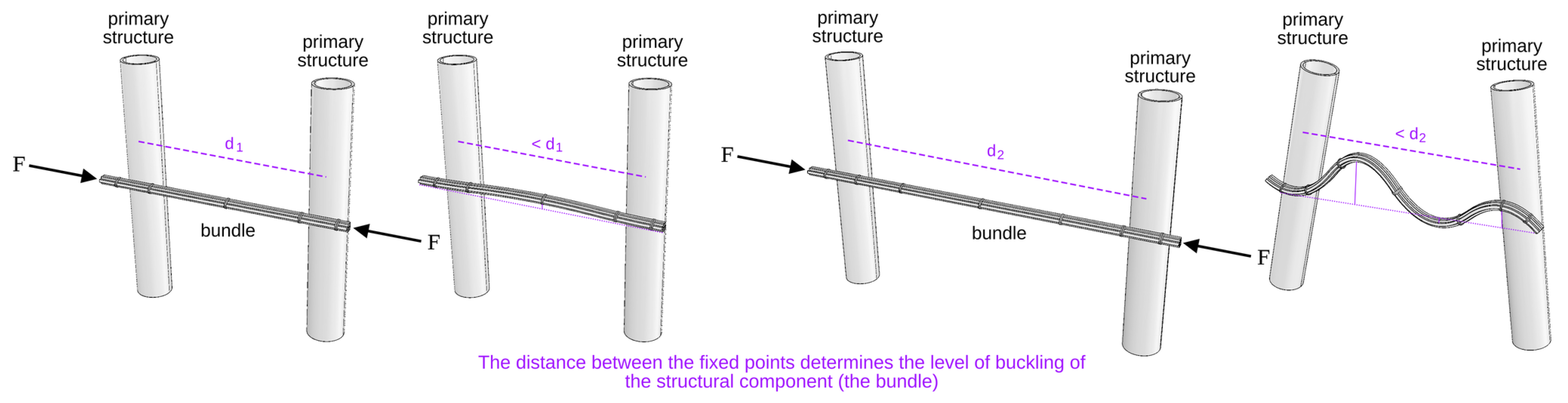

Lidi-bundle. It is true that the fewer the splits in a bundle, the more flexible it becomes, which is advantageous for tracing spatial curves of varying curvatures. However, this flexibility reduces its structural performance, especially in compression (buckling).

Naturally, the spacing between two intersection points (where the bundle is fixed) plays a crucial role in stiffening the structure, even with the same number of splits in the bundle. As depicted in

Figure 11, smaller distances between fixed points result in less buckling, whereas larger distances lead to more significant buckling issues.

In the case of our bamboo structure, as illustrated in

Figure 12, this was not a primary concern because as the bundle containing fewer splits approached the highest point of the spatial curve, the distances between the primary structural elements decreased incrementally. This arrangement provided a balanced structural stiffness and significantly reduced the buckling effect.

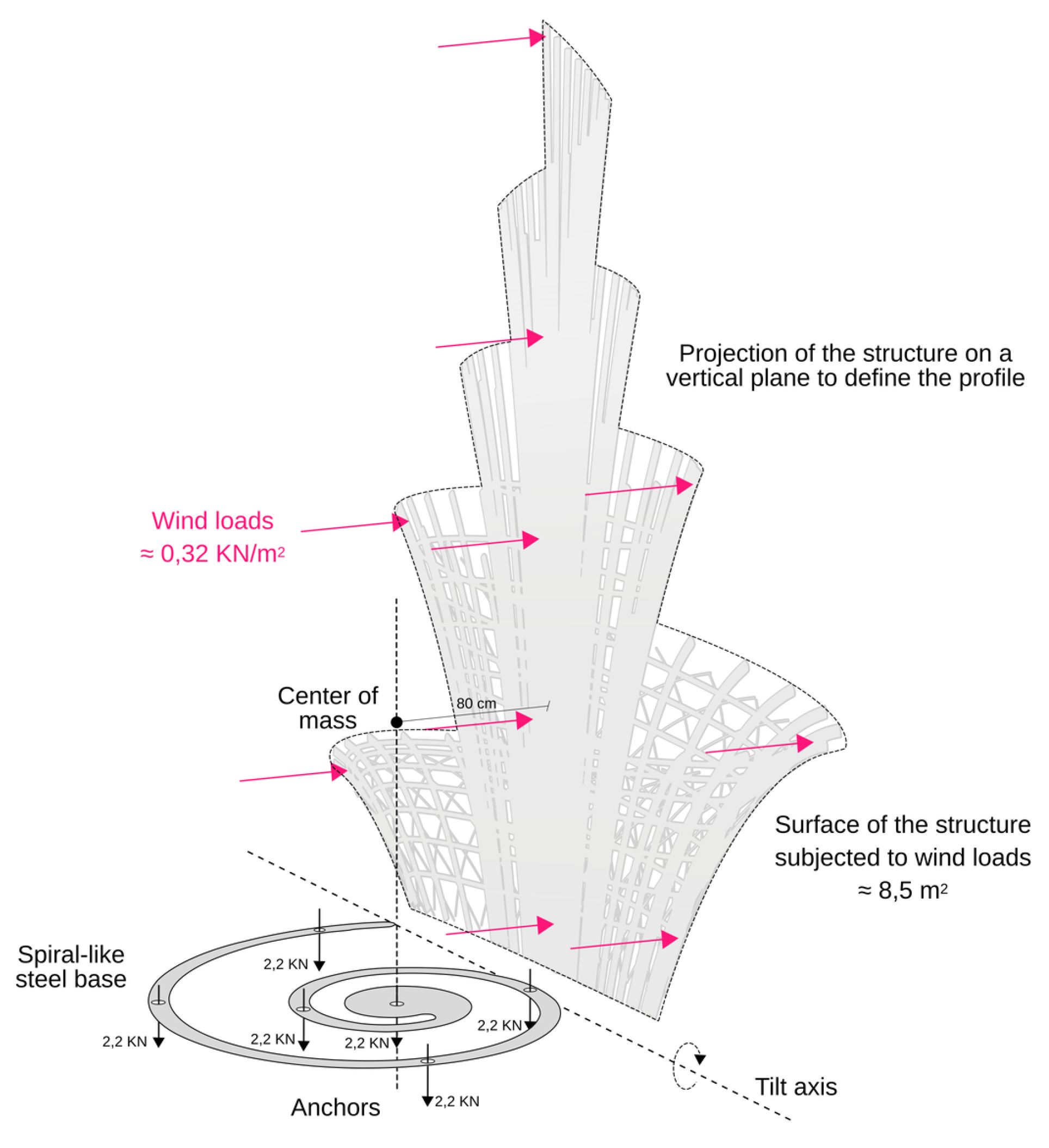

• Component 03: Foundation → Base + Pins Due to the particularities of the site and the ephemeral nature of the structure, designing the foundation had to address several concerns. These included potential damage to the grass, narrow access points, and most importantly, ensuring the overall stability of the structure. Initially, we considered creating a steel base to which all the bamboo poles could be fixed. The base would need to be sufficiently heavy to resist tilting without requiring additional anchoring. The rationale behind this was that the structure, being lightweight and inaccessible, would not experience significant deformation under its own weight. If the base could resist tilting under wind loads, it would eliminate the need for anchors. However, the ends of the primary structure form a spiral shape, which means the tilting axis is a straight line intersecting the endpoint of the spiral and tangent to the furthest point of curvature. The center of gravity is only slightly eccentric to the origin of the spiral. Additionally, the floral shape of the structure results in an extremely narrow base, with a distance from the tilting axis to the center of mass of

80 cm, as depicted in

Figure 13. Ultimately, a stability test under wind loads was conducted, which involved determining:

The total surface area of the structure subjected to wind loads was 8.5 m². This calculation was performed by projecting the profiles of the structure onto a vertical plane placed along the tilting axis.

The wind loads were determined in accordance with DIN 1055-4:2005-03, considering that the structure is located in Pillnitz, which corresponds to wind zone 1.

Taking into account the wind loads according to DIN 1055-4:2005-03 for wind zone 1, with safety factors.

This resulted in a moment load of 6 kNm and indicated that relying solely on a steel base as a counterweight was not feasible. Therefore, the alternative choice was to anchor the structure to the ground. Cantilevering the base was ruled out for aesthetic reasons. As a result, the foundation was designed as follows:

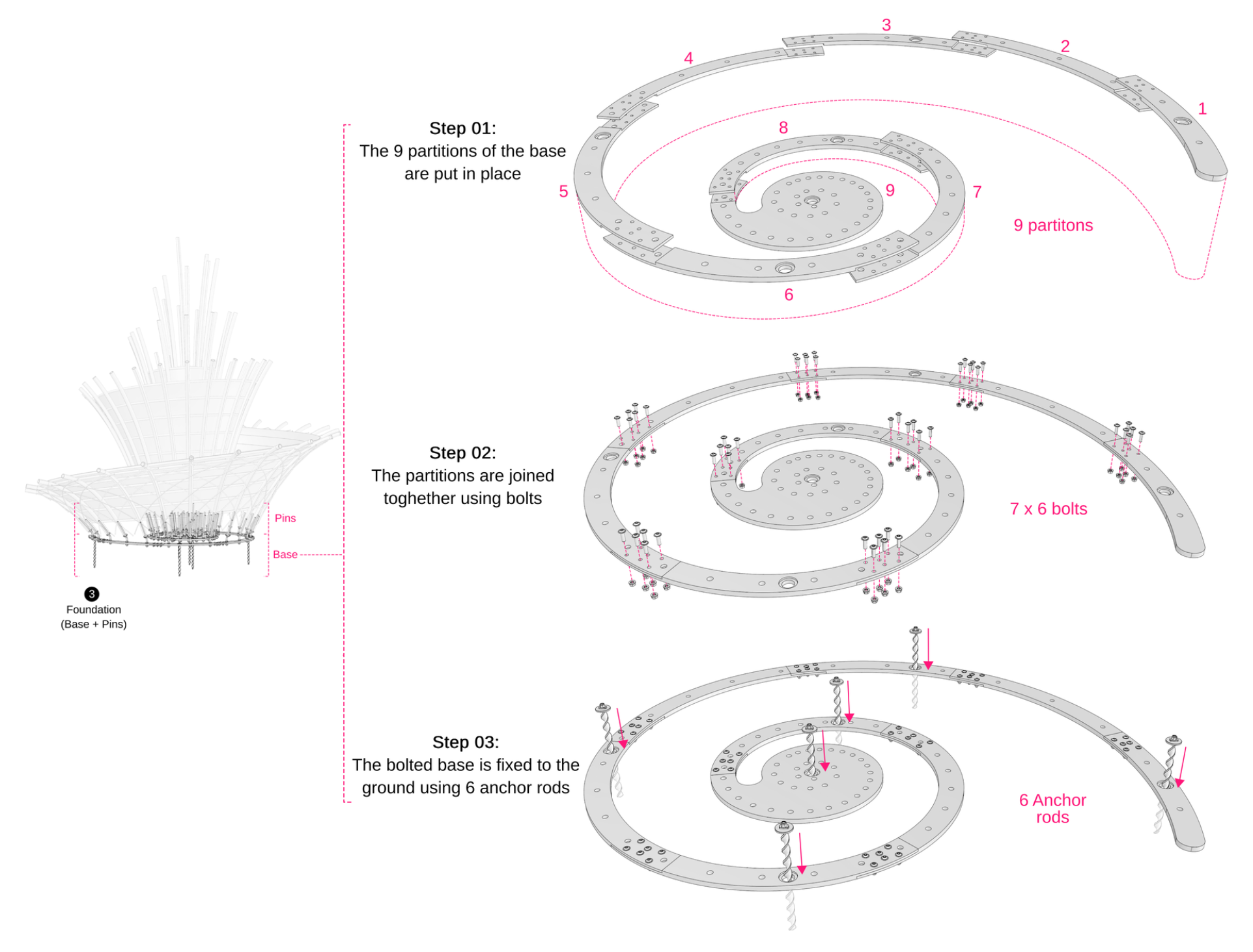

The Base: The design of the base, as depicted in

Figure 14, features a spiral-like stainless-steel sheet divided into nine partitions joined together by bolts. Eight partitions are approximately 100 cm long, 10 cm wide, and 2 cm thick, while the central partition measures approximately 70 cm long, 60 cm wide, and 2 cm thick. This spiral design follows the ends of the primary structure (

Rup-rup poles)and reflects the filigree nature of the overall design. Anchor points are integrated into the base at the center and at five evenly spaced points. The partitions are designed for easy manual handling, simple installation, and transportation, as detailed in (

Section 3.2). Once bolted together, the entire base is secured to the ground using six anchor rods, each 50 cm long and 4 cm in diameter. These anchors feature a spiral surface with a high pitch, allowing them to be hammered into the ground and unscrewed with minimal damage.

The anchors may appear oversized, but they are selected to meet regional codes assuming sandy soil conditions. They provide a pull-out resistance of 2.3 kN under challenging conditions, ensuring they can withstand the calculated moment load effectively.

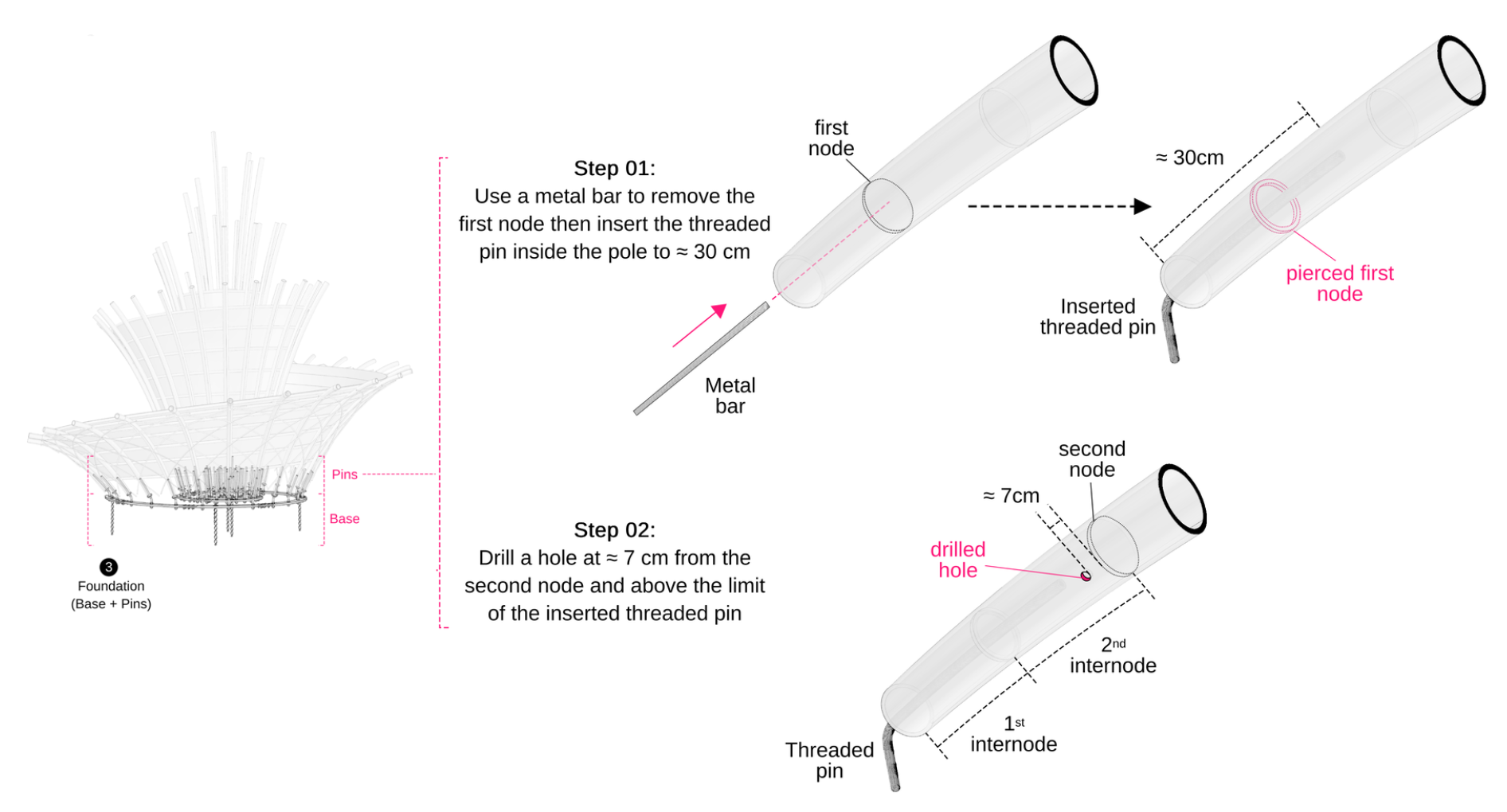

The Pins: This component details the rigid connection that links the primary structure to the steel base, inspired by bamboo metal connectors pioneered by architect Simón Vélez and demonstrated in [

5]. This connection involves affixing a metal pin or bar to one end of each bamboo pole, which is then securely bolted or screwed to the foundation.

Figure 15 illustrates the initial steps in implementing this connection: firstly, the first node of the primary structure (as depicted in

Figure 6: Step 07) is pierced using a metal bar, allowing for the insertion of a threaded pin ≈ 30 cm into the pole.

Subsequently, a hole is drilled into the pole’s wall ≈ 7 cm below the second node ([

5,

11]). It is noteworthy that due to the non-vertical orientation of the

Rup-rup poles in relation to the base, and the impracticality of using a hinge connection due to kinematic constraints, a rigid connection approach was chosen. This involved bending 70 threaded rods to 70 unique angles to ensure secure attachment to the foundation. In

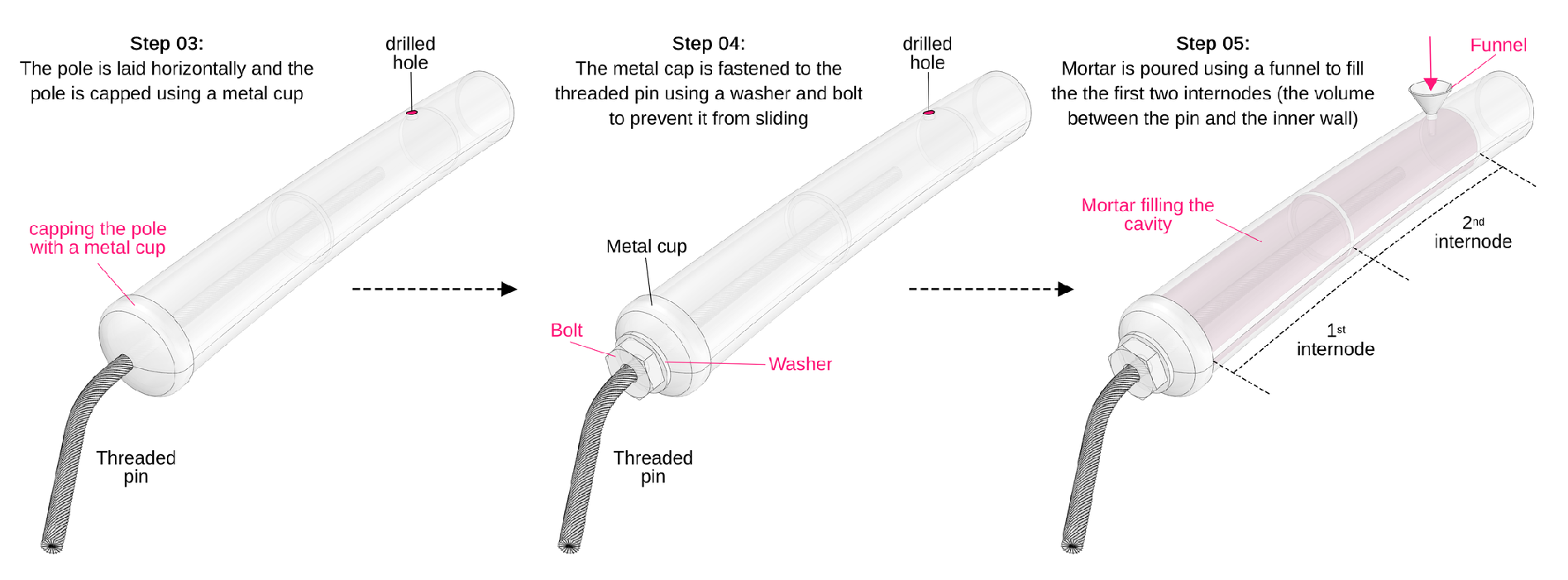

Figure 16, the process continues by capping the end of the pole with a metal cup (a pierced clinker base used for sealing metal pipes), which is secured to the threaded pin using a washer and bolt to ensure a tight seal. Through the drilled hole, using a funnel, mortar (details of its properties below) is poured into the cavity (the first two internodes) until it fills completely. This process securely attaches the threaded pin to the pole while preventing the pin from pressing against the wall and potentially causing fractures under load.

As mentioned earlier, mortar was utilized to fill the cavity between the pin and the pole wall.

Table 2 outlines the composition of the mortar developed for this purpose. An accelerator was incorporated into the mixture to expedite the hardening process, and particles with a maximum size of 1 mm were used due to the dimensions of the drilled hole. The objective was to prepare a mixture that is sufficiently liquid to be poured easily, yet capable of setting quickly to accommodate the project’s tight schedule. The mortar was prepared in batches of 5 liters using a Hobart SHM30 mixer. Initially, the dry components were mixed for 3 minutes at the first speed (approximately 68 rpm). Subsequently, water containing an accelerator was added and mixed at the same speed for an additional 1 minute.

Afterward, superplasticizer was introduced, and the mixture was agitated at a higher speed (approximately 178 rpm) for 4 minutes.

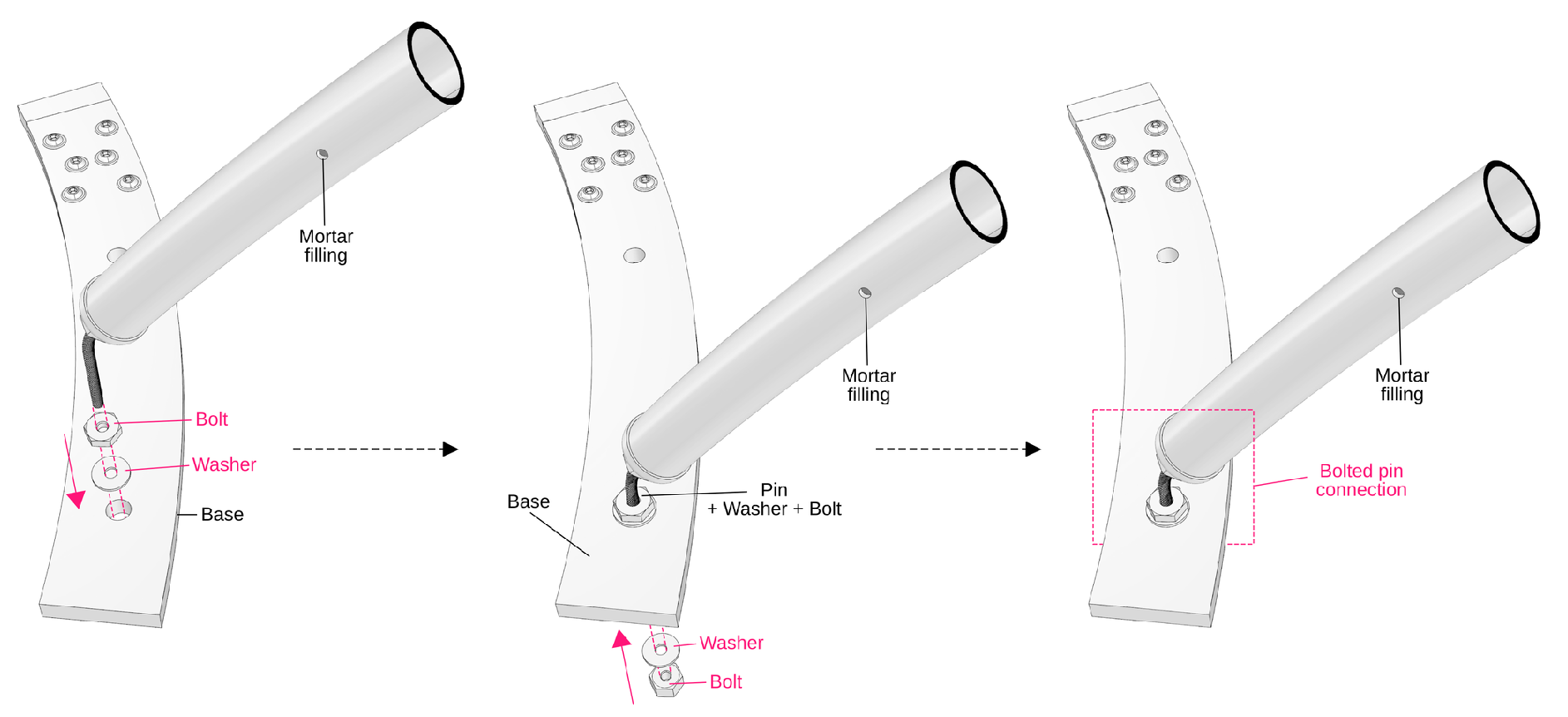

It’s noteworthy that the compressive strength of the mortar was later tested after 28 days using 40 mm cubes, yielding an average value of 101 MPa. Once the mortar had set, the two components (base + threaded pins) were secured together using washers and bolts, as depicted in

Figure 17. This method ensures a robust connection that withstands structural loads while maintaining the integrity of the bamboo pole and its anchored base.

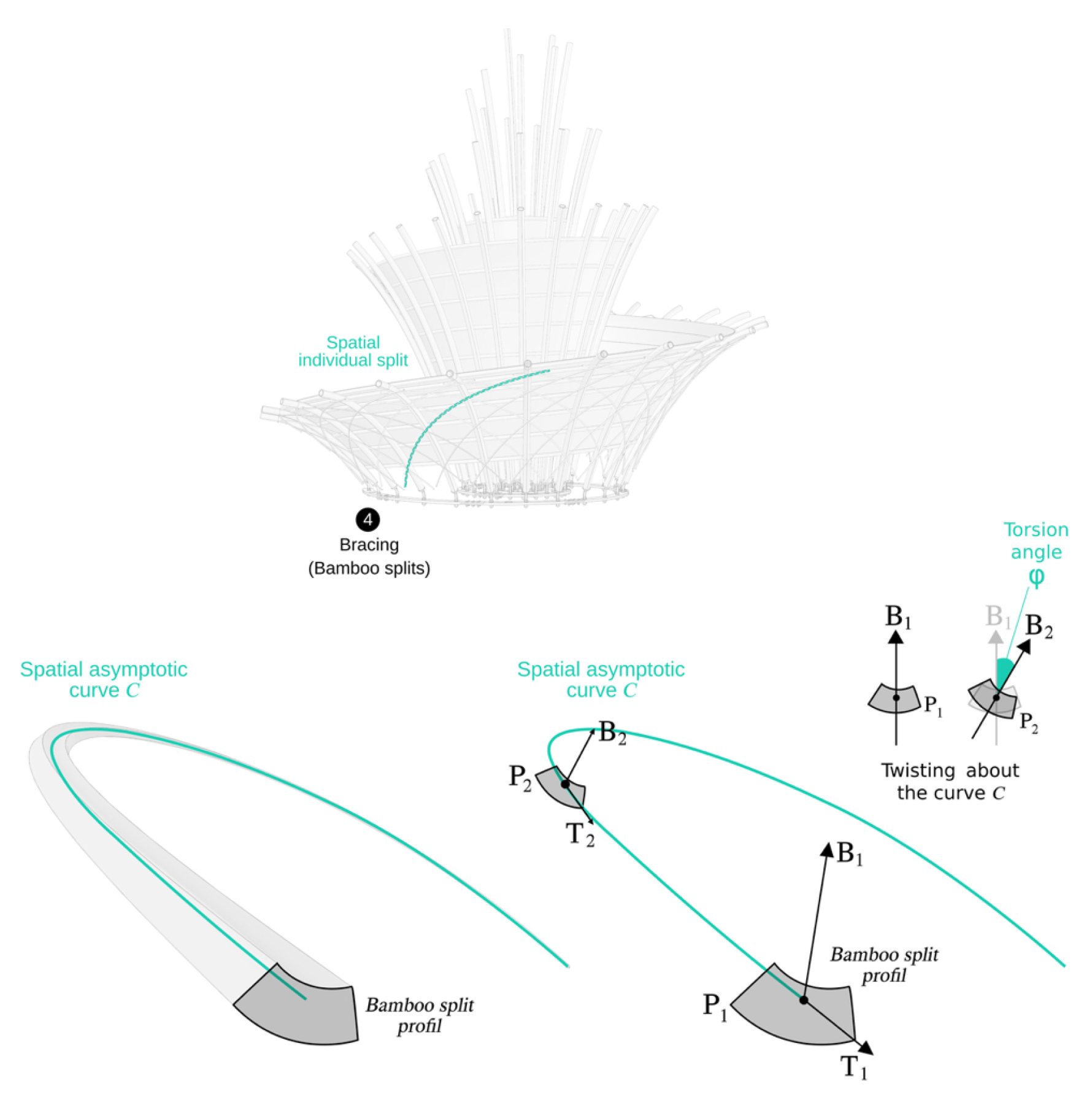

• Component 4: Bracing → Bamboo splits Note that, the structure is braced using "thin" longitudinal bamboo splits, as demonstrated in

Figure 10 (Step 02). These splits trace specific network curves originating from the asymptotic patch that bisects both the primary and secondary structures, as highlighted by [

1,

2].

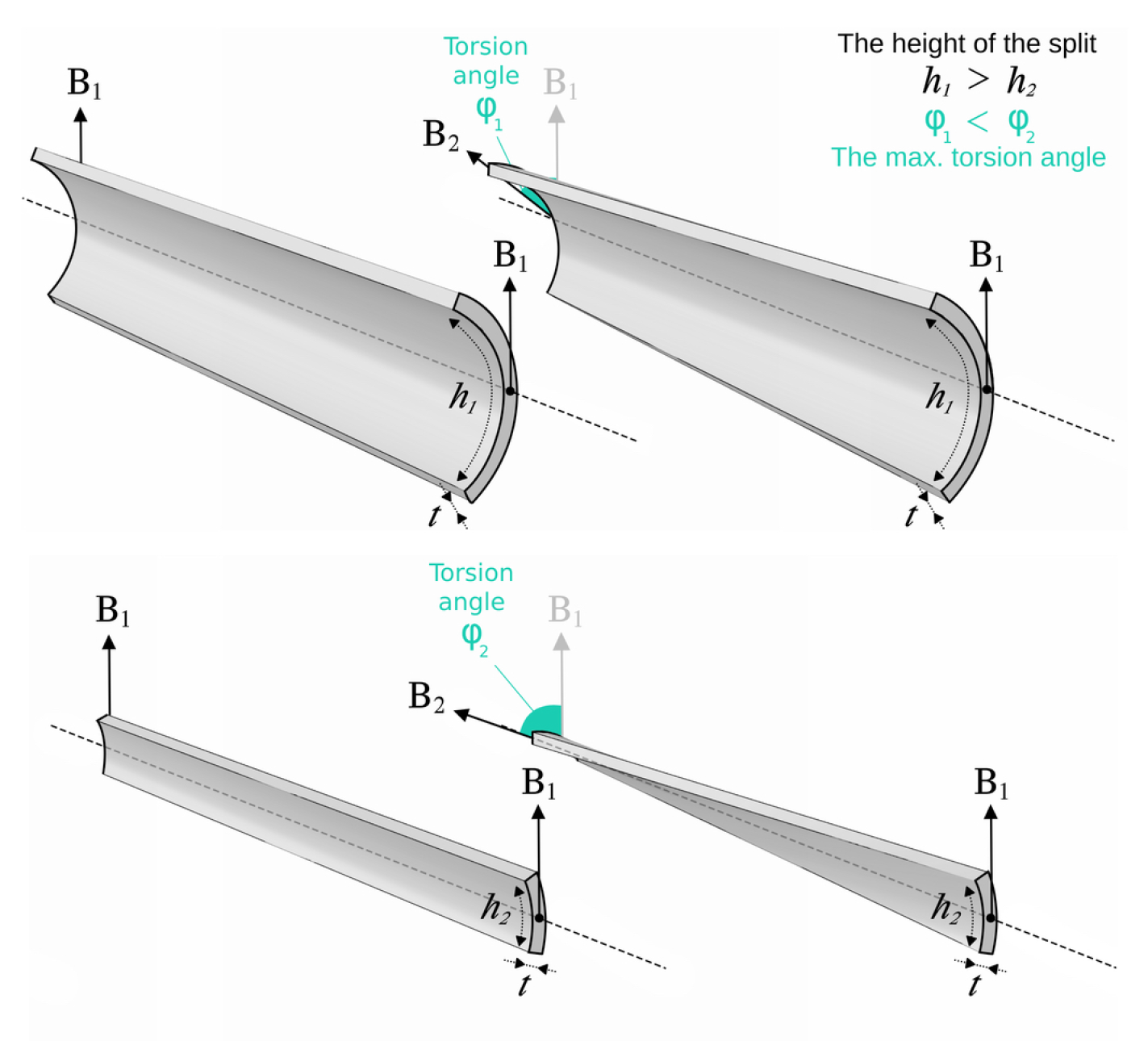

It is important to note that while a bamboo split tracing an asymptotic curve may exhibit slight curvature, its significant characteristic is the torsion angle or twist angle . Mechanically, denotes the rotation of the profile or cross-section about its longitudinal axis. Geometrically, it represents the angle between the binormal vector at point and the binormal vector at point in the plane perpendicular to the tangent vector .

We have three main structural factors: cross-section of the split, distance between intersection points, and number of splits. In the case of bracing with individual splits, our primary concern was the correlation between the cross-section h and twisting capacity .

Figure 19.

Relation between height and twisting.

Figure 19.

Relation between height and twisting.

3.2. Falsework-Free Construction

Falsework serves as a temporary support structure that holds discrete structural components in place until they are joined together and the structure becomes stable [

9]. While the vast majority of constructions require some form of temporary support during assembly, conventional falsework methods for complex or non-standard constructions are often costly, generate significant waste, and rely heavily on digital fabrication facilities [

6,

7]. Although there have been explorations into bending-active or reusable falseworks, these approaches remain experimental and are typically limited to certain types of doubly curved shapes [

6] and some recent work on construction Without Formwork by [

8]. To address these challenges and considering project constraints outlined in

Table 1, we have pursued a falsework-free construction approach. This method utilizes the prefabricated primary structure (as depicted in

Section 3) as a foundational support for assembling other structural components that require active bending, such as the secondary structure and bracing elements. By adopting this strategy, we circumvent the complexities associated with conventional falsework, including high costs and installation challenges.

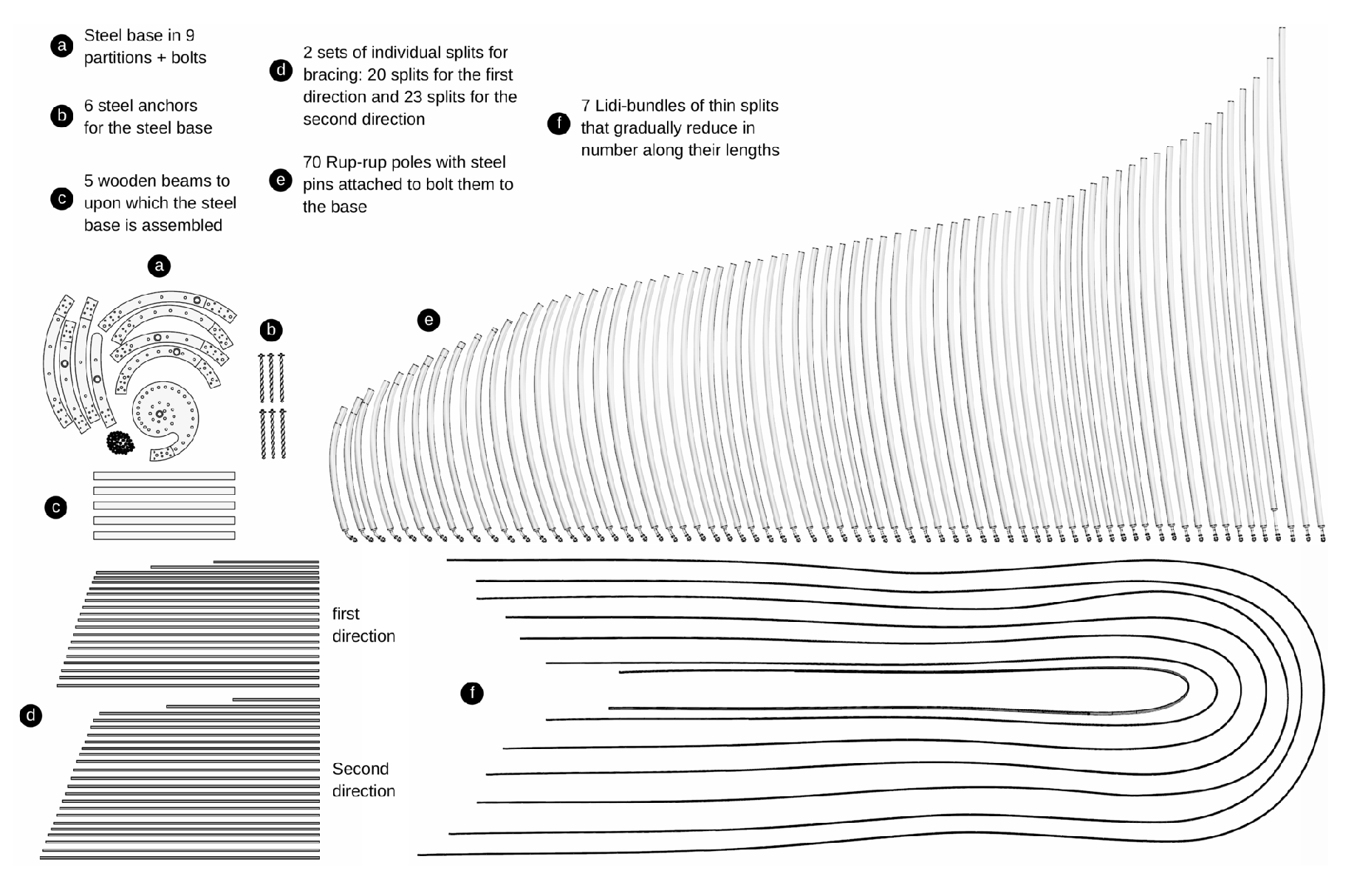

• Layout of the structural components: In

Figure 20, we can see a layout of the prefabricated structural components, including the steel base with its anchors, the bracing splits divided into two sets, the

Rup-rup poles with steel pins attached, the

Lidi-bundles of splits, and wooden beams.

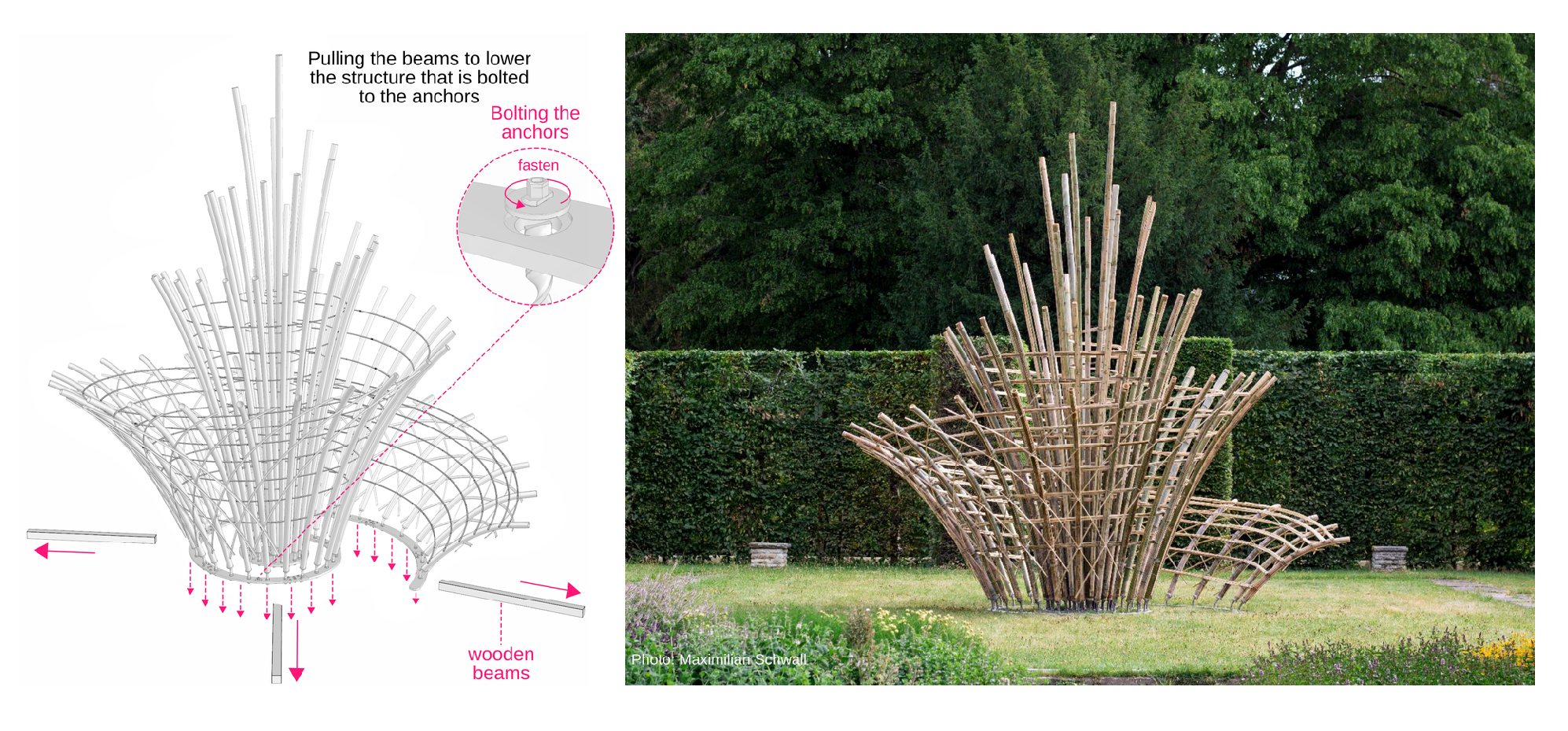

• Sequence of assembly without falsework:

The decision to opt for on-site assembly of prefabricated structural components without falsework was motivated by several factors, some of which were highlighted in

Table 1, particularly those linked to the nature of the construction site. The sequential, falsework-free assembly of prefabricated structural components proceeded as follows:

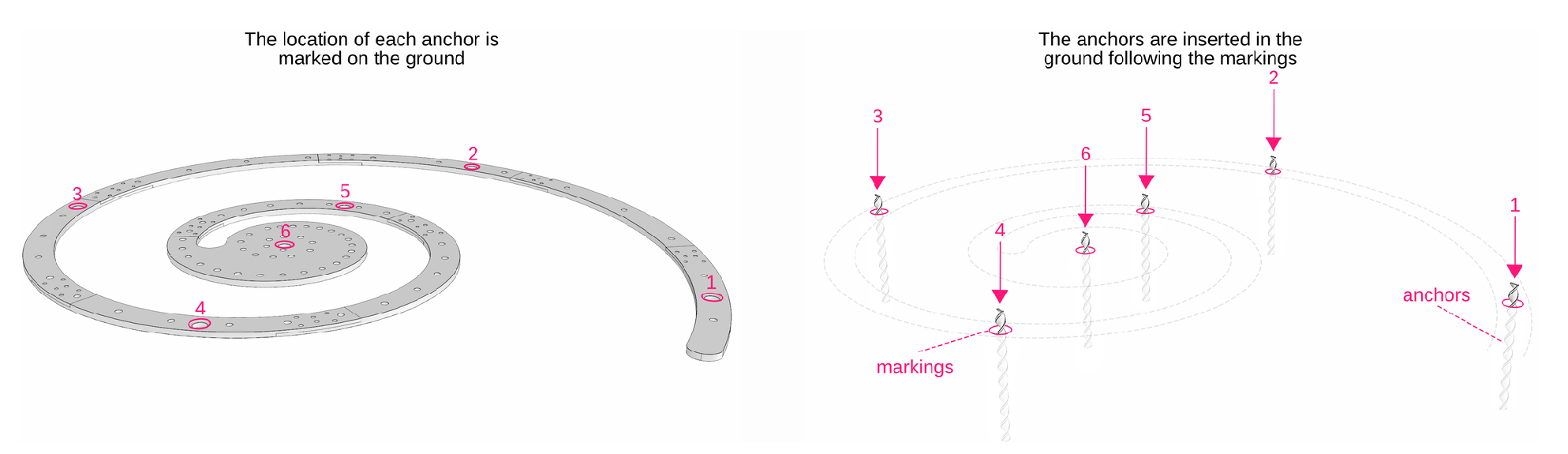

Step 1. First, we begin by placing the partitions of the steel base (unbolted) in their correct positions on the ground to mark the locations of the 6 anchors, as depicted in

Figure 21 (left). Once this is completed, the partitions of the steel base are removed, and the anchors are inserted into the ground, as shown in

Figure 21 (right).

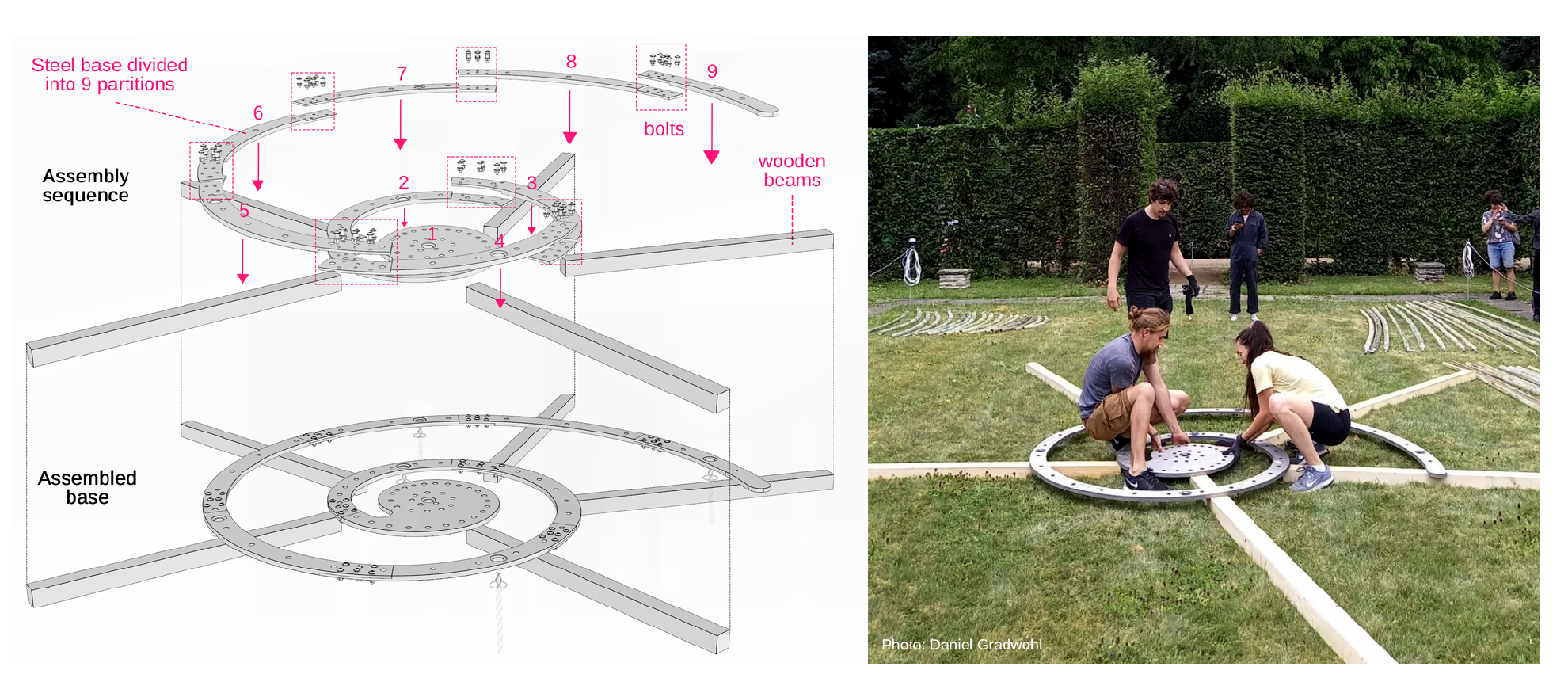

Step 2. Next, we reassemble the steel base, which consists of 9 partitions, over 5 wooden beams as illustrated in

Figure 22. The wooden beams create enough space underneath the steel base to allow access for bolting its partitions together and later assembling the primary structure onto the base. This ’shallow’ foundation with a small footprint was chosen to comply with site restrictions, being less invasive and not damaging to the grass. Dividing the base into parts facilitates easy transportation by stacking them, handling through narrow pathways, and installation without heavy machinery.

Step 3. Following that, we install the first batch of 6

Rup-rup poles (primary structure) onto the base. First, we align them according to the markings made on both the base and the poles beforehand. Then, the poles are securely fastened in place using bolts, accessible via the space underneath the elevated steel base, as depicted in

Figure 23. Due to their rigidity, the

Rup-rup poles are easy to install without rebounding. They also serve as a form of falsework or guide for tracing the secondary structure.

Step 4. Once the first batch of the rigid

Rup-rup poles is securely installed, we begin elastically bending the

Lidi-bundles of splits one by one into position against the

Rup-rup poles, following the earlier markings. We then screw them sequentially onto the poles, starting from the innermost pole outwards, as shown in

Figure 24. Due to the Dini’s particular shape that narrows towards the center, we alternate between bolting batches of the

Rup-rup poles to the base and screwing the

Lidi-bundles onto them. This alternating process is repeated until all components of the primary and secondary structures are assembled.

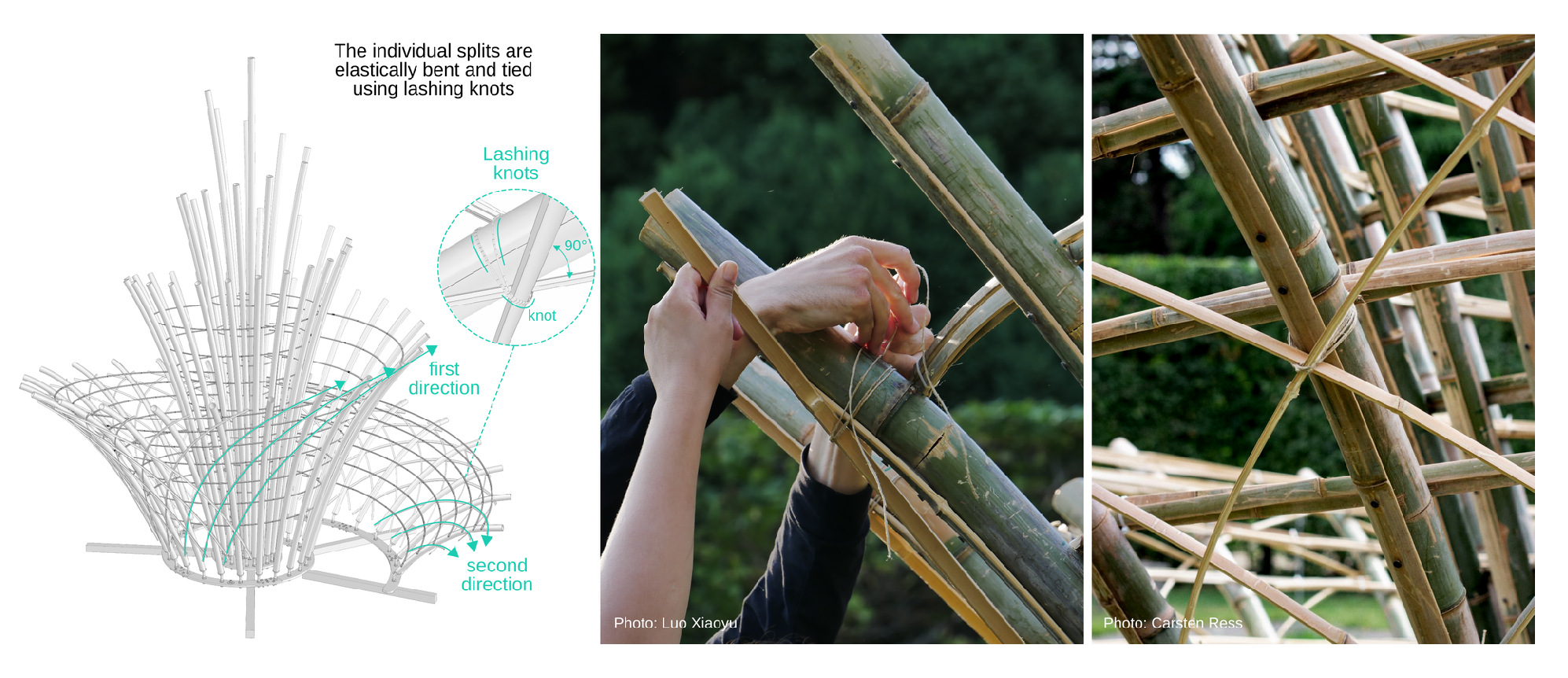

Step 5. Having assembled the primary and secondary structures (Rup-rup poles and Lidi-bundles of splits respectively), both sets of the bracing elements made from individual bamboo splits.

These are elastically bent to trace diagonally and bisect the orthogonal intersections between the primary and secondary structures (as explained in Sub

Section 2.1). Once in place, the bracing elements are tied to the structure at those intersection points using traditional lashing knots (courtesy of artist

Masayo Ave), as shown in

Figure 25. These lashing knots ensure a secure and stable connection, enhancing the structural integrity of the assembly, and contributing to the aesthetic appeal of the design.

Step 6. Finally, the wooden beams beneath the steel base are gradually pulled out, lowering the base until it rests securely on the ground ensuring precise alignment and stability. Once the base is in its designated position, the structure is fastened in place using bolts, securing it to the anchors previously inserted into the ground, as depicted in

Figure 26.