1. Introduction

The overarching thematic context for this article is the topic of sustainable and ecological green city and building design. In response to the increasingly negative impact of human transformation of the Earth’s global and local environments, the United Nations formulated the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a call for action [

1]. This includes the impact of urbanisation and construction which is addressed as part of SDG 11 on “Sustainable Cities and Communities”. Yet, it stands to reason that SDG11 cannot be addressed in isolation. In order to accomplish sustainable cities, urban climate plays a vital role, as does the question of ecology and biodiversity and the necessary resource water to accomplish green cities. This points towards the vital role of SDG 13 on “Climate Action”, SDG 15 on “Life on Land”, and SDG 6 on “Clean Water and Sanitation”. And, furthermore, the intended impact of sustainable and ecological green cities is human health and well-being, as related to SDG 3 “Good Health and Well-being”. Alarmingly, the United Nations 2024 report on the global progress towards the SDGs in the period from 2015 to 2024 shows only medium progress on SDG 11, marginal progress mixed with stagnation or regression on SDG 3, SDG 6, SDG 13, and SDG 15 [

2]. A corresponding report provided by EUROSTAT on the European context shows a similar result for the recent 5 year period [

3], in spite of the announcement of the announcement of the announcement of the “European Green Deal”, which recognises climate change and environmental degradation as “an existential threat to Europe” [

4].

The linkage and dynamic interaction between the different SDGs implies that stagnation or regression of some or several SDGs negatively impacts on the development of other SDGs. We argue therefore that in order to accomplish green and ecological cities and buildings these linkages need to be closely considered and dealt with on equal hierarchical level. One item that is of great importance in this context is soil. The European Environment Agency pointed out that many SDGs “cannot be accomplished without health soils and sustainable land use” [

5]. We propose to address the question of the linkage and dynamic interaction of the above listed SDGs and soil within the framework of

critical zone (CZ) research [

6]. CZ research focuses on “the heterogeneous near-surface environment in which complex interactions involving rock, soil, water, air and living organisms regulate the natural habitat and determine the availability of life-sustaining resources” [

7]. CZ research is an interdisciplinary research field involving hydrology, geomorphology, soil science, sedimentology, geochemistry, biology and ecology, as well as climatology. Embracing the systems that make up the critical zone entails that the way sites are prepared for construction and how construction is executed is no longer viable. Typically, the preparation of construction sites entails the removal of vegetation and often also significant amounts of soil, resulting in massive alteration or destruction of local soil and water regimes. This can be especially observed in urban densification areas where soil is frequently removed (and precipitation water is channelled away leading frequently to concurrent drought and flooding) to make way for often multi-storey underground basements and parking, thereby making it difficult if not impossible to support biodiversity and urban ecosystems.

In the context of the European Horizon 2020 Future and Emerging Technology research project ECOLOPES - ECOlogical building envelopes, we argue that even intensive greening of leftover spaces, such as streets, courtyards, and balconies, is not sufficient in providing a game-changing approach to making cities substantially more green, ecological, biodiverse, and healthy (e.g., humans benefiting from increased human-nature interaction and ecosystem services. Instead, we argue that in order to significantly expand the space and surface available for the species that inhabit or could inhabit urban environments, the exterior surfaces of buildings, in other words building enclosures or envelopes, need to be utilized for the purpose of multi-species design, providing adequate spaces, conditions and resources for plants, animals and (soil) microbiota.

This then is also the aim of the research, namely to develop a conceptual and methodological framework that enables practitioners in architecture and planning to design ecological building envelopes. The overarching question is therefore how to integrate architectural and ecological domain knowledge into a conceptual and methodological framework and how to derive a valid design workflow for ecological building envelopes and as key part of this a computational design workflow and related tools that.

Doing so requires an interdisciplinary approach that involves architects, landscape architects, ecologists, and computer and data scientists, in order to develop an adequate computational framework, workflow, and tools [

8,

9,

10]. The partners in the ECOLOPES research project work on a variety of aspects of this conceptual, methodological and computational framework, including ecological models [

11,

12], performance of urban soils [

13], criteria for multi-species design [

14], the initial computational design process (portrayed in this article), multi-criteria decision making [

15] and optimization process [ref] and validation processes for both the design outcomes [

16] and the usability of the approach in architectural practice, etc.

In this article we portray the conceptual framework for the initial or early stage design process for ecological building envelopes, which we term “ontology-aided generative computational design process”. In the results section we first describe the key concepts that underlie our approach, followed the design cases for which we develop the design process, the key computational components, our computational design workflow, and finally the way we validate the ability of architects in training to uptake and work within the conceptual and methodological framework set forth thus far.

2. Materials and Methods

The research portrayed in this article required a mixed-method approach. To undertake a detailed inquiry into the state-of-the-art of various topics we produced scoping literature reviews that have been published separately. These literature reviews were paralleled by a narrative literature review to establish a theoretical framework, principal approach and key concepts that ground and frame this research. This led to the formulation of a computational design workflow for the early design stage of ecological building envelopes, which we term ontology-aided generative computational design process, followed by identifying required computational components and tools.

The conceptual development phase of the

ontology-aided generative computational design process was paralleled by a process of validating whether architects in training, in this case master-level students at TU Wien, were able to comprehend the defined approach, key concepts, as well as the intended workflow. For this purpose we conducted six consecutive master-level design studios focused on defined design cases. Research-through-design, research processes that utilize design as mode of inquiry, played a key role in the work with master-level students in the dedicated design studios. As Lenzholzer et al. pointed out that design “can be research, provided it complies with the procedures, protocols and values of academic research [...] Creswell [

17] described three different types of research strategies: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed. He further distinguished four substantially different worldviews within which these approaches can be applied: (post)positivist, constructivist, transformative, and pragmatic. Regardless of the worldview, the choice of the appropriate research strategy is always guided by the research question(s)” [

18] (p. 59). In accordance with the definitions provided by Cresswell and Lenzholzer et al., we employed pragmatic research (real-world problems, mixed method approach), with elements of the (post)positivist approach (physical, prescriptive, generalisable, quantitative) and the constructivist approaches (new forms, contextual, qualitative, inductive). In our case, the pragmatic approach employs mixed methods for the purpose of testing design hypotheses, form generation and computational evaluation based on simulation tools . In this context, the below described computational components and the computational workflow were developed through a series of design experiments conducted in master-level design studios at TU Wien, followed by phases of conceptual and technological advancement performed by the research team.

In order to facilitate the development and operation of a data-driven design process for the purpose of designing ecological building envelopes it is necessary to have access to and operate on multi-domain and multi-scale spatio-temporal datasets. Required datasets either already exist or need to be generated. Multi-domain datasets also need to be structured and correlated. Open-access data provided in the municipal geoportal of the City of Vienna [

19] was used as a starting point of the computational design process. The developed design process requires typical raster datasets provided by municipal portals, such as Digital Surface Models (DSM) and Digital Elevation Models (DEM). The DSM dataset describes the height values of buildings and vegetation, while the DEM is constructed by extracting and interpolating heights of the terrain. Additionally, orthophoto data containing point colors and land-use classification data were sourced from the municipal geoportal and included in the ECOLOPES Voxel Model. Open source software frameworks, such as QGIS (v. 3.22) and SAGA GIS (7.9.1) were used for GIS data processing. Finally, the whitebox tools [

20] were used to execute environmental analysis, i.e., locally specific solar and wind exposure of a given site. The analysis results were stored as a series of raster layers and imported into the ECOLOPES Voxel Model to inform the data-driven and ontology-aided generative computational design process.

3. Results

In this section we first describe the key concepts that we developed on the basis of which an early stage design process for ecological building envelopes can be developed, followed by an outline of the practice-based design cases that we address. Thirdly we describe the computational components that are required for our approach, followed by an elaboration of the computational workflow. Finally, we describe how we used master-level architecture studios to validate whether architects are able to uptake the necessary key concepts that provide design aims, as well as the conceptual aspects of the design workflow.

3.1. Principal Approach and Key Concepts

In this section we describe our principal approach to early-stage or initial design of ecological building envelopes. In principal terms, we aim for a computational design approach that can iteratively along a number of defined steps generate different design outcomes, e.g., generation of design variation, whereby each individual design can be validated and all design variants can be ranked and accordingly selected for optimization. This is not a novel approach as the possibilities of generating design variation have been recognised as early as in the 1970s [

21]. The general idea behind generating multiple outcomes is that complex design problems can be better tackled when there is a possibility to analyse different outcomes in relation to a list of different domain specific performance criteria, i.e., architectural as well as ecological criteria. Given the multi-domain and multi-scale characteristics of this approach to designing building envelopes this entails a series of domain-specific datasets and requirements that cannot be tackled by a planner or architect alone. To support this type of design it is therefore necessary to provide decision-support to designers, especially concerning requirements of other domains, i.e., ecology, and also in relation to cross-domain relations and items, i.e., linked architectural

and ecological items or relations. Linked to that is the need to deploy different domain-specific spatio-temporal and multi-scale datasets that are required for rule-based and data-driven design processes. These aspects are not only important from a methodological perspective, but instead need to be comprehended from a conceptual perspective to enable meaningful engagement with the ontology-aided generative computational design process.

In our ongoing research we have examined, developed and used data-driven methods for analysing and understanding environments, as well as for designing environments [

22]. In this context we have shown that in order to advance data-driven approaches for understanding and designing environments it is necessary to employ a multi-domain and a multi-scale approach in relation to spatial, temporal and functional scales. Moreover, we have shown that it is useful to link analytical and generative workflows for the purpose of addressing multi-domain design problems.

Two key concepts have been identified for the purpose of developing the ontology-aided generative computational design process. The first concept concerns nodes and network relations.

3.1.1. Networks, Nodes and Relations

The comprehension of relations between items expressed in networks is a central approach in our research. We approach this topic from an actor-network theory perspective. Dwiartarma and Rosin explained that “actor-network theory (ANT) asserts that agency is manifest only in the relation of actors to each other. Within this framing, material objects exert agency in a similar manner to humans. (…) ANT (…) asserts that any entity that exists within the social system is meaningful because of the network of relationships it shapes with others (...) To account for this attribution of meaning, ANT uses the term actant to distinguish its conception of an actor as embedded within network relationships (…) An actant is thus defined as ‘an effect generated by a network of heterogeneous, interacting, materials’ [

23]” [

24] (p.28). In the context of our research nodes network relations framed within an ANT perspective includes ecological networks (e.g., the relation between local species), human-nature interactions (e.g., the relation between humans and other species in an ecological network), and the relation between architectural items and features and ecological items, e.g., local species (including the resources required by them). Establishing these nodes and networks is our inroad into preparing instructions for design, as discussed in

Section 3.4. Furthermore, such nodes or items and their relations also underlie the preparation of computational ontologies and knowledge graphs, as well as the selection of relevant datasets for the design process, as shown in

Section 3.3.

3.1.2. Urban LandForm

The following fundamentally challenges the currently prevailing understanding of urban form and the form of buildings, and regarding the latter also their status as discrete technical objects that are clearly separate from their surroundings.

The study of urban form or urban morphology, has been described as “the science of form, or of various factors that govern and influence form” [

25]. Araújo de Olivera stated that “urban morphology means the study of urban forms, and the agents and processes responsible for their transformation; and that urban form refers to the main physical elements that structure and shape cities - streets (and squares), street blocks, plots, and common singular buildings, to name the most important” [

26] (p. 2). The problem we perceive that is associated with understanding urban morphology or urban form as an assemblage of discrete systems and objects is that this approach foregrounds what separates items, by placing emphasis on the distinction between systems, spaces and objects, and thereby on the features that separate them. The understanding of urban form as a set of discrete items and systems, evolved from a tradition of surveying (as can, for instance, be seen in the work of Giambattista Nolli, e.g., in his survey of Rome (1736-1748)). This survey is shown as a so-called

figure-ground map, which separates a figure (building) from a background (urban surface), and thereby built space (object) from unbuilt space. This separation of figure from ground led to an understanding of the architectural object as a discrete item [ref], i.e., building, that is clearly set apart from its surroundings. In this context the question arises whether an approach based on dissociation of items and hence emphasis on boundaries and discontinuity is best suited as a framework for planning and design when the design task requires correlating and operating on overlapping and extensive territories and exigencies of different actors in urban ecosystems. This question can be formulated as follows: What is the most adequate framework for understanding urban form and architectures in the context of the objectives of promoting urban ecosystems and biodiversity?

Regarding urban ecosystems it is necessary to foreground connectivity, which necessitates deriving an approach to emphasize connection and common features, rather than separation and distinct features. This is highlighted by the recognition that the way cities are organised and divided into a mosaic of plots, resulting in fine-scale heterogeneity, runs counter to requirements for landscape connectivity. Landscape connectivity “has been recognized for its importance to dispersal, foraging, species interactions, population persistence, gene flow, and evolution [

27] [...] these processes are notoriously difficult to observe empirically [...] [yet] Measuring and maintaining these ecological processes may be more important than ever in the face of intense anthropogenic impacts, such as climate and land cover changes [

28]. Urban ecosystems have unique properties and have the potential to uniquely contribute to local, regional, and global biodiversity” [

29]. Lookingbill et al. pointed out that “urban areas are pervasive and growing, and landscape connectivity is one of the key drivers that shape urban evolutionary dynamics [

30]. Understanding the impact of urbanization on movement of organisms and eco-evolutionary processes will be important for long-term sustainability of urban areas and global biodiversity [...] In social-ecological systems such as cities, landscape connectivity may be an indicator of resilient systems that are able to persist, adapt, and transform in response to disturbances and change [

31,

32]” [

33] (p. 2).

In this context we propose an approach that we term Urban LandForm, which introduces a hybrid condition that fuses urban form and systems and landscape form and systems to achieve a continuous and continuously varied urban terrain or landscape in which the different systems and objects, e.g., buildings, partake. This is in itself not an entirely new approach. Two precedents or influences need to be pointed out. The first is the notion of first landscape urbanism, later repositioned as ecological urbanism and second the notion of landform buildings.

Waldheim explained that “‘ecological urbanism’ has been proposed to [...] describe the aspirations of an urban practice informed by environmental issues and imbued with the sensibilities associated with landscape [...] Ecological urbanism proposes [...] to multiply the available lines of thought on the contemporary city to include environmental and ecological concepts, while expanding traditional disciplinary and professional frameworks for describing those urban conditions” [

34] (p. 179). This approach resonates with the research portrayed in this article but does not incorporate the building scale in a sufficiently defined manner. The landform building approach initially seems to close that gap. Stan Allen stated that: “Throughout the decade of the 1990s, architects looked increasingly to landscape architecture – and later to Landscape Urbanism – as models for a productive synthesis of formal continuity and programmatic flexibility … Landform Building traces an alternative history of architecture understood as artificial landscape … [and] repositions conventional understandings of object and field – architecture and landscape – within the new domain of contemporary ecological theories” [

35] (pp. 22, 30-31).

However, the buildings associated with the landform buildings approach did generally not fully deliver the incorporation of ecological theories, nor fundamentally different types of constructions that incorporate provisions for multiple species and local ecosystems. A systematic approach was lacking that would relate questions of form to microclimate and biodiversity. Recent research on the relation between geodiversity, microclimate variation, and biodiversity may fill this gap. Landform can be instrumentalised as a way of providing geodiversity, which entails geological and geomorphological diversity [

36]. More specifically geodiversity entails “the natural range (diversity) of geological (rocks, minerals, fossils), geomorphological (landform, processes) and soil features” and “their assemblages, relationships, properties, interpretations and systems” [

37]. Geodiversity is a key factor in influencing local environmental conditions like microclimate [

38], thereby providing a useful way of modulating microclimate on an architectural scale and on urban scales. Furthermore, recent research has shown that geodiversity supports the provision of ecosystem services [

39] , as well as biodiversity [

40,

41]. Tukiainen et al. elaborated that “Geodiversity is an emerging, multi-faceted concept in Earth and environmental sciences. Knowledge on geo-diversity is crucial for understanding functions of natural systems and in guiding sustainable development. Despite the critical nature of geodiversity information, data acquisition and analytical methods have lagged behind the conceptual developments in biosciences. Thus, we propose that geodiversity research could adopt the framework of alpha, beta and gamma concepts widely used in biodiversity research. ... Thus, this study not only develops the geodiversity concept, but also paves the way for simultaneous understanding of both geodiversity and biodiversity within a unified conceptual approach” [

42].

Approaching Urban LandForm from a geodiversity perspective in support of biodiversity, requires examining how to consider relevant correlations between varied landform and the varied conditions that derive from them, as well as the dynamics that shape these diversities. In order to do this systematically a system of defining land form or terrain features is needed. A detailed description of our approach to this topic is provided in

Section 3.4 Computational Workflow.

3.2. Design Cases

In order to develop a design workflow that is relevant for practice we decided to address the two most common design cases that occur in architectural practice.

Design case 1 entails the design of a master-plan for a given site. In this case the number and distribution of buildings, including building footprint, floor area ratio, maximum volume, and maximum height are typically not defined and the purpose of the design case is to determine these items. In the context of this research this entails that spatial organization through the distribution of architectural, biomass and soil volumes (for design case one we refer to these as primary volumes), as well as geometric articulation of site and buildings (for design case one we refer to this geometry as primary landform). This makes it possible to derive continuous landform across the site including all buildings as part of this landform.

Design case 2 entails the design of individual buildings for which all constraints such as building footprint, floor area ratio, maximum volume and building height etc are already defined by an existing master-plan. Since the maximum volume is already given and hence the primary volume is given and to some extent the primary geometry is limited in modification due to given constraints, this design case is to partition a primary volume into secondary and tertiary architectural, biomass and soil volumes. In a second step the specific building geometry that is secondary and tertiary landform is derived that can enable access for different species to the biomass volumes, especially if these are elevated above ground.

3.3. Computational Components

Three key components were developed for the ontology-aided generative computational design process, which include: (1) the EIM Ontologies that guide the design process in its different stages and can be queried by the designer, (2) the ECOLOPES Voxel Model that integrates relevant datasets for the design process, (3) the ECOLOPES Computational Model that generates design outcomes in the Rhinoceros 3D environment. A fourth part is a designer interface in the Rhinoceros 3D Grasshopper environment. The approach to the first three components is described in the following Sections.

3.3.1. EIM Ontologies & Knowledge Graph

Ontology is a technical term referring to an artifact designed to model the knowledge of a domain of discourse at a certain level of detail [

43], more specifically, it as an explicit and formal specification of a shared conceptualization [

44]. A conceptualisation is an abstract and simplified model of a domain of application that needs to be represented. Ontologies make it possible to conceptually and formally model the domain, by specifying the relevant concepts, and the relations between them in a consensual manner. There exist a large number of ontologies that are published online in RDFS or OWL ontology languages with the aim of reusing the domain knowledge in a standardized form.

Knowledge graphs increase interoperability by expressing explicit facts or statements using an ontology [

45]. Concepts and relations from the ontology as a unified schema are used to describe, and therefore align various data sources. In addition, axioms in ontologies are used to reason with explicit facts in the knowledge graph in order to deduce implicit facts. Another definition states that “Knowledge Graphs are very large semantic nets that integrate various and heterogeneous information sources to represent knowledge about certain domains of discourse” [

46].

To establish the current state-of-the-art and research gaps we undertook a scoping literature review regarding the use of information modelling and computational ontologies in planning, designing and maintaining urban environments [

47].

The EIM (Ecolopes Information Model) ontologies, developed in collaboration with domain experts and adhering to Semantic Web and Linked Data best practices, serve as a mediator between life sciences data (e.g., species distribution and habitats) and geometric information (e.g., maps, voxel models of building structures). In this context, the ontologies and the knowledge graph are used to answer different questions that are asked by the designer, or so-called “competency questions”. Usually competency questions are used to define the scope of the knowledge graph and identify the gaps in knowledge in a feedback manner. A detailed technical description of the development of EIM Ontology 1 (Knowledge Graph) has been published separately [

48].

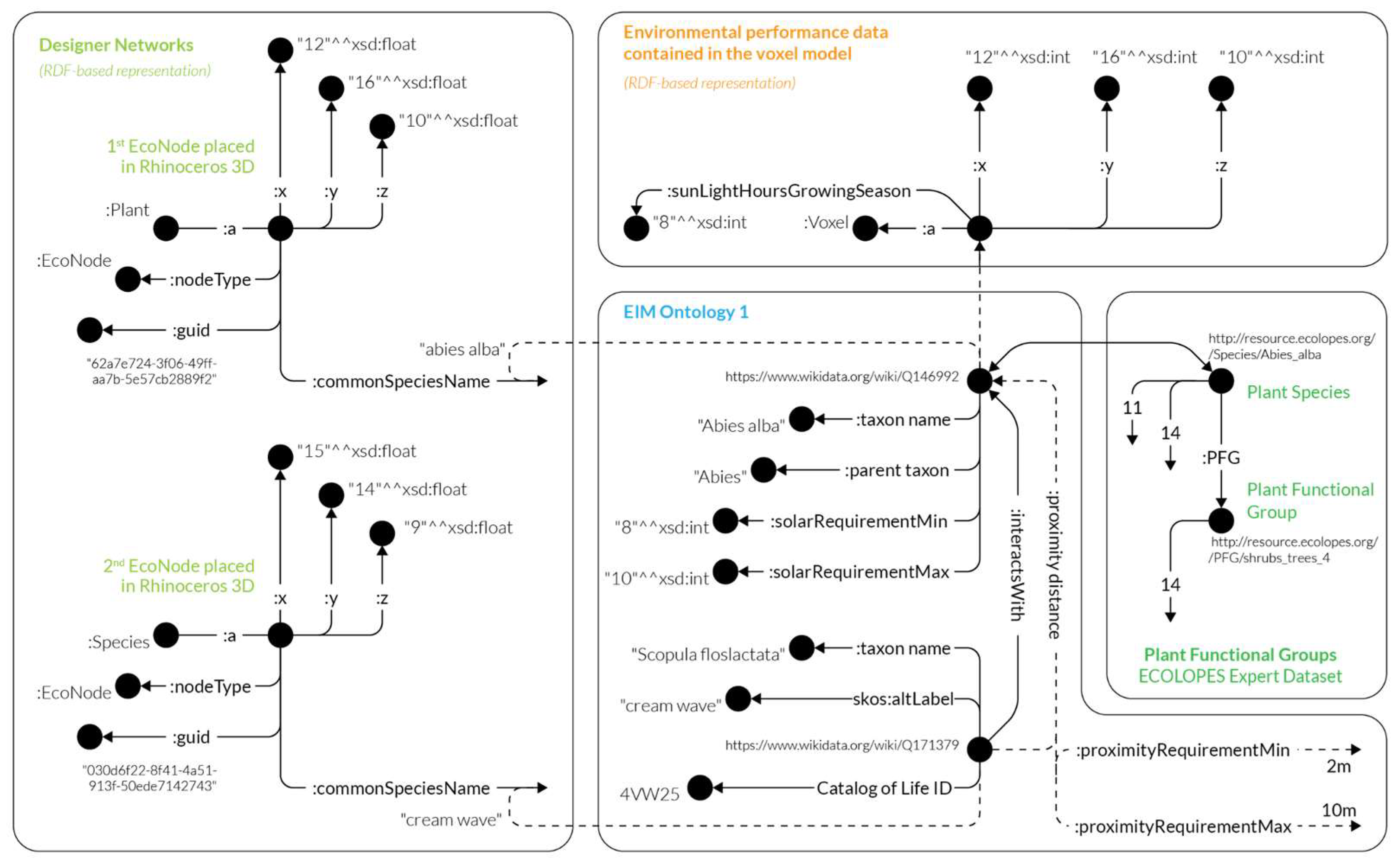

Figure 1.

This figure show a diagram of EIM Ontology 1 (Knowledge Graph) that describes species metadata, including interactions to other species, their proximity requirements, as well as crossovers to other parts of the knowledge graph including designer networks (deduced based on species common name), PFGs and data contained in the voxel model respectively (deduced based on coordinates).

Figure 1.

This figure show a diagram of EIM Ontology 1 (Knowledge Graph) that describes species metadata, including interactions to other species, their proximity requirements, as well as crossovers to other parts of the knowledge graph including designer networks (deduced based on species common name), PFGs and data contained in the voxel model respectively (deduced based on coordinates).

3.3.2. ECOLOPES Voxel Model

To commence the research on voxel models we undertook a semi-systematic literature review on the role of voxel models in supporting data-integrated design processes [

49]. Voxel models are conventionally understood as 3D equivalents of 2D pixels, typically visualized as spatial aggregations of 3D box-shaped geometries. Each of the 3D box-shaped volumes is placed on a regular grid of 3D points, referred to as voxel

nodal points. Often individual 3D boxes are visualized in different colors, representing properties assigned to the individual

nodal points. Although voxel models are commonly associated with their box-based 3D representation, the actual definition of a voxel model states that “each voxel is a unit of volume and has a numeric value (or values) associated with it that represents some measurable properties or independent variables of a real object or phenomenon” [

50]. Voxel models can be represented as collections of 3D boxes, 3D spheres or rendered as continuous isosurfaces. An important property of a voxel model is its capacity to represent or encode numeric values that represent real world properties of studied objects. By developing computational methods that make it possible to integrate diverse datasets and engage the end users with the voxel-based representation of real world objects, we see our approach to be aligned with Srihari’s definition of voxel models as “spatial-knowledge representation schemata” [

51].

The ECOLOPES voxel model contains and correlates multi-domain spatialized data for the design process and its interactions with other components of the ontology-aided generative computational design process for ecological building envelopes. Technically it is implemented in a database system, enabling real-time interaction with the ontology and 3D CAD environment, to enable designers to evaluate complex spatial constraints and work with multi-dimensional data in multiple scales [

52]. The integration of voxel- and ontological modeling is one of the central aims of this research, and builds up on the RDB technology to implement an interoperable voxel modeling environment, establishing an interactive link with ontologies implemented in the GraphDB environment. The technical implementation of the ECOLOPES Voxel Model is based on anticipating varied levels of computational proficiency on the part of the designer. For this reason an easy-entry solution was chosen in the format of relational databases, i.e., SQL databases, which are widely implemented. User interaction will be realized through the ECOLOPES front-end tools based on the Rhinoceros 3D & Grasshopper CAD environment, which is widely used in architectural design (see

Figure 2). The detailed development of the ECOLOPES Voxel Model has been reported in a separate article [

53].

3.3.3. ECOLOPES Computational Model (Rule-Based Process)

We employ a rule-based computational model based on the designer’s input that constitutes the input for generating design outcomes. This approach computes the design outcomes based on the selected rules that can be run in a designated order. The selected rules can range from the selection of solar requirements, proximity constraints, to the more elaborate in terms of space such as the rules for volume spatial distribution or the generation of the geometry, i.e., geometry articulation. The ECOLOPES rule-based process is orchestrated by the Grasshopper 3D environment and the results are visualised in the Rhinoceros 3D CAD interface. The generation of design outcomes varies based on the selection of rules and their respective order of application. The rule-based computational model is used to generate design variations for spatial organisation and geometric articulation (Urban LandForm) as described in

Section 3.4 Computational Workflow.

To facilitate interaction with ontologies, we selected to use a RDF triple store to store and manage the knowledge graph and ontologies. Each triple store implements a SPARQL endpoint functionality that allows the knowledge graph and ontologies to be queried or updated. The rule-based approach is implemented by running a set of SPARQL queries in a specified order to achieve the intended result. SPARQL endpoint provides basic reasoning capabilities by enabling execution of SPARQL queries, namely the CONSTRUCT type queries, which are used to mimic the rules within a rule-based process [

54]. This can be achieved by running a set of SPARQL CONSTRUCT queries in a designated manner, representative of consecutive steps in a rule-based process. Our approach facilitates this rule-based processes, based on the designers’ interaction within the Rhinoceros 3D and Grasshopper environment. Designers are able to execute individual steps within the rule-based process, by executing a series of Grasshopper components for predefined SPARQL queries. This approach enables simple interaction between the designers and the ontologies within a familiar computational design environment.

In the context of Loop 1, the implementation of rule-based process provides designers feedback on the placement of ArchiNodes and EcoNodes, which represent provisions for ecological and architectural functions. Currently, the rule-based system evaluates proximity and solar requirements constraints between all Nodes placed by the designer. To satisfy both the proximity and solar requirements, a sequential rule-based process is employed. A series of SPARQL queries is executed, inferring if the first requirement is satisfied, followed by the second requirement evaluation, etc. This assures generalization of the approach, allowing for an arbitrary number of requirements. In the case of proximity requirements, spatial requirements of the EcoNodes and ArchiNodes placed by the designers are represented as

proximityMin and

proximityMax relations computed within the environment hosting the ontology. In the case of solar requirements, information on the solar exposure of each location needs to be retrieved from the ECOLOPES Voxel Model. Currently, the voxel model contains solar exposure information for each location on the case study site where the designers can place an EcoNode or ArchiNode. The ECOLOPES Voxel Model is implemented within an Relational Database (RDB) framework, mapping information on solar exposure throughout the year to dedicated columns in the database, Moreover, this information is interactively linked with the knowledge graph. To achieve this we employed a set of mappings that allow the voxel model – stored in a RDB – to be virtualized as a knowledge graph. The mappings basically specify how each column of a table (or a query) in RDB is mapped to an ontological term, thus exposing it as a knowledge graph using the ontological terms specified in the mappings. This data integration framework is called OBDA [

55] (Ontology-based Data Access). This functionality is available off-the-shelf in the triple stores such as GraphDB. In the context of virtualisation, the knowledge graph is not (physically) stored, meaning that the SPARQL queries are translated to SQL queries on-the-fly against the voxel model stored in RDB.

In the context of Loop 2 and Loop 3, the ontology-aided rule-based process provides ongoing feedback on the placement of individual volumes and the generation of geometric expression, as described in the

Section 3.4.2. The generative process. In the generative process, a series of design solutions is generated in the interaction between the designers and computational components constituting the rule-based process. In Loop 2, designers define the

initial generation criteria, such as the amount of architectural, soil and biomass volumes and the rule-based process generates a series of

spatial organizations that fulfill both the

generation criteria and the spatial constraints between the individual volumes. For example, placement of each biomass volume is constrained by the spatial constraint, requiring a biomass volume placed directly underneath. To initiate the rule-based process implemented for Loop 3, designers define the starting criteria by selecting a single

spatial organization created in the previous Loop and defining target values for the evaluation criteria, such as geodiversity. Multiple geometric solutions are generated for the selected spatial solution and the evaluation criteria as described in

Section 3.4.2. The generative process. Designers are interacting with the rule-based process in Loop 3 by adjusting the target values for the evaluation criteria, based on the interactive 3D visualisation in the Rhinoceros 3D CAD environment. By making an informed decision, supported by the proposed computational process, designers can accept the current geometric solution and materialize the generated geometry as standard 3D CAD surfaces within the Rhinoceros 3D environment.

3.4. Computational Workflow

Two distinct processes make up the workflow of the ontology-aided generative computational design process: (1) the

translational Process and (2) the

generative Process.These two processes, described in the following

Sections, consist of three distinct sequential steps that we refer to as loops.

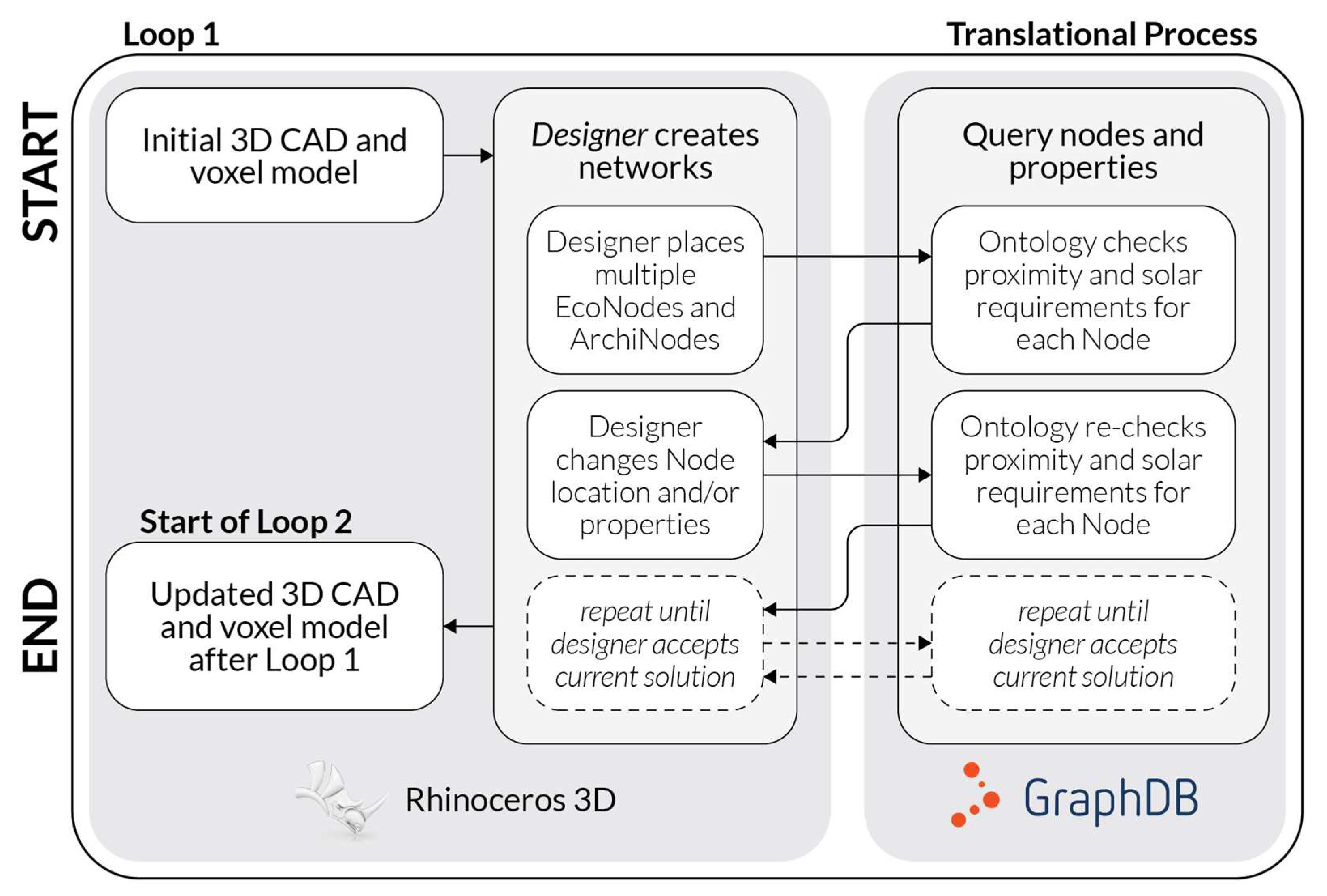

Figure 3 shows the complete generalised workflow.

3.4.1. The Translational Process

The

translational process comprises Loop 1 (

Figure 4), in which the designer analyses, correlates, and locates spatially architectural and ecological requirements contained in a given design brief, as well as design-specific determinations, while taking into consideration relevant constraints (i.e., planning regulations). The key components of Loop 1 are EIM Ontology 1 in the format of a knowledge graph that can be queried by the designer, and datasets contained in the Ecolopes Voxel Model that can be utilized by the designer in the process of preparing required input for the generative computational design process.

Figure 4.

This figure describes the translational process, which comprises Loop 1 in which the designer creates networks, by placing ArchiNodes and EcoNodes in the Rhinoceros 3D CAD environment. The spatial configuration of the network nodes is evaluated by the rule-based process to check the proximity and solar requirements, providing computational feedback for the designer.

Figure 4.

This figure describes the translational process, which comprises Loop 1 in which the designer creates networks, by placing ArchiNodes and EcoNodes in the Rhinoceros 3D CAD environment. The spatial configuration of the network nodes is evaluated by the rule-based process to check the proximity and solar requirements, providing computational feedback for the designer.

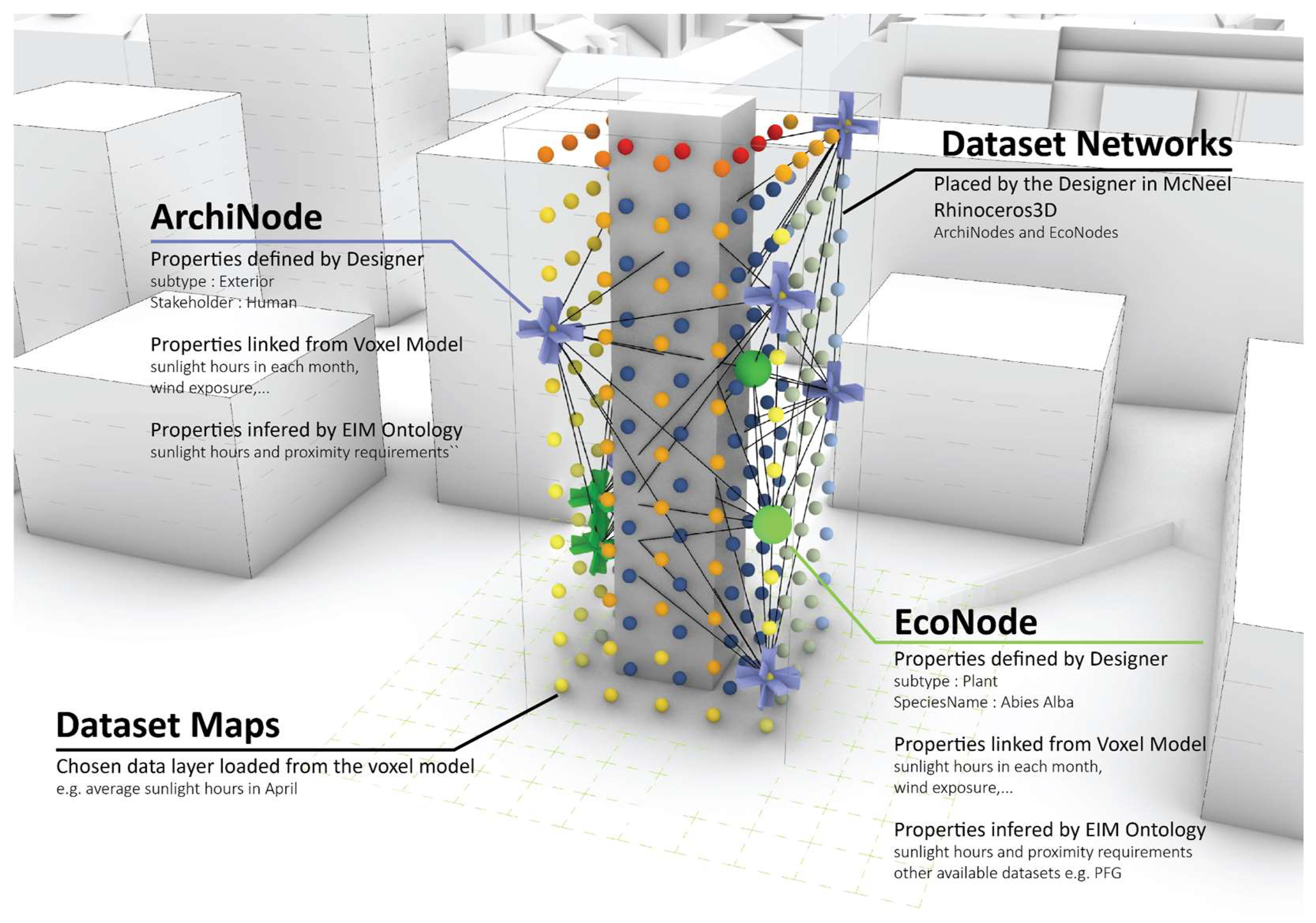

Figure 5.

Visual representation of the Loop 1 results in which designers create networks by placing EcoNodes and ArchiNodes based on the feedback provided by the dedicated components of the computational framework.

Figure 5.

Visual representation of the Loop 1 results in which designers create networks by placing EcoNodes and ArchiNodes based on the feedback provided by the dedicated components of the computational framework.

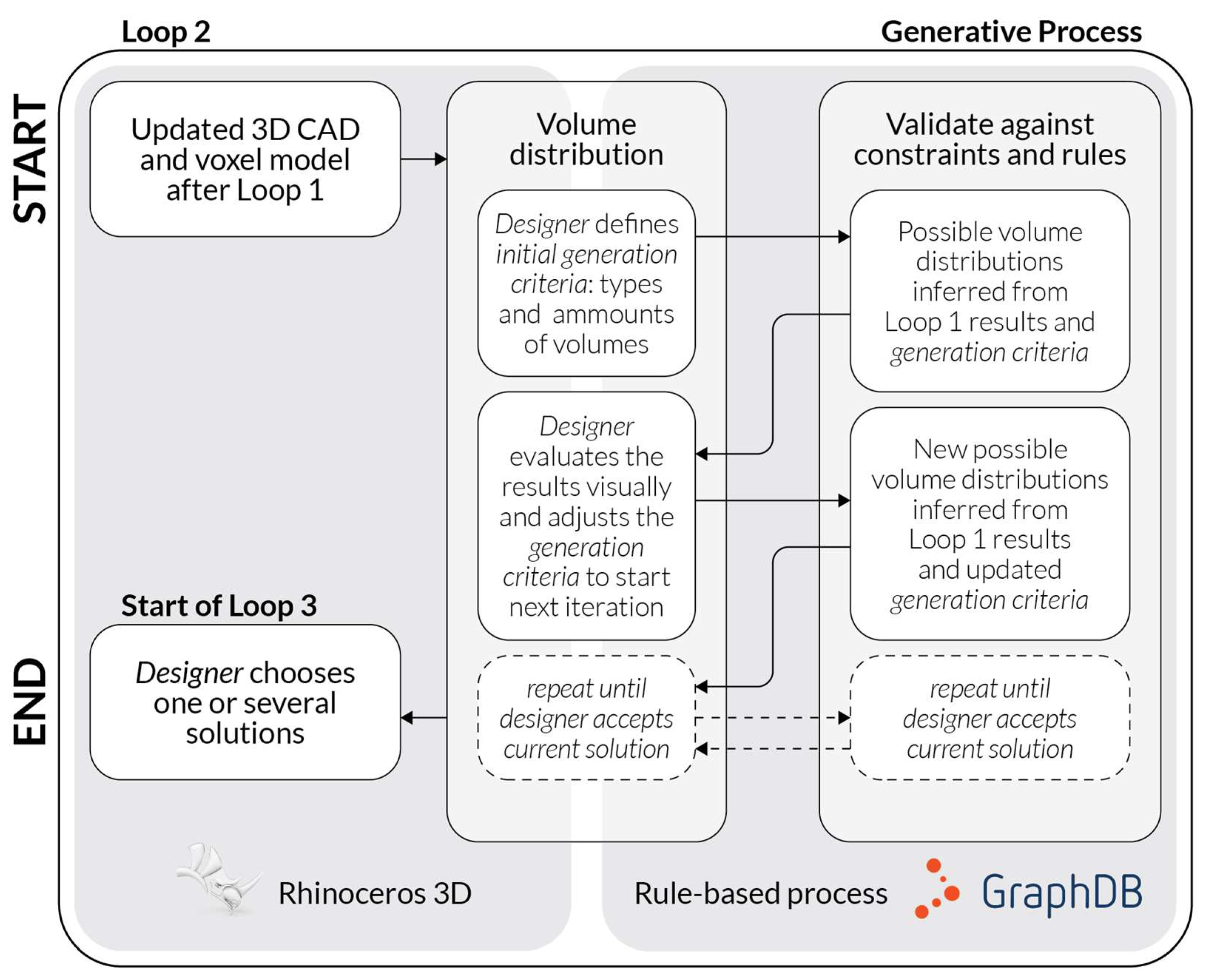

3.4.2. The Generative Process

The

generative process comprises Loop 2 (

Figure 6) and Loop 3 (

Figure 8). In Loop 2 variations of spatial organization are generated and evaluated. In Loop 3 specific surface geometries are generated for selected outputs of Loop 2. The outputs are then evaluated according to defined criteria, i.e., key performance indicators. Design outputs combine 3D geometry in the Rhinoceros 3D software, datasets contained in the ECOLOPES Voxel Model, as well as ontological output.

For the purpose of deriving spatial organization we defined three distinct types of volumes: (1) architectural volumes that indicate either buildings or parts thereof, (2) biomass volumes, and (3) soil volumes (

Figure 7). Together these three types of volumes constitute the spatial organization of an

ecolope. For design case 1 (masterplanning) this entails spatial organization of the entire site or plot. For design case 2 (building design) this entails spatial organization of the permitted building volume defined by planning regulations. We anticipate that in the process of developing the approach each principle volume type will need to be developed into subtypes, e.g., dense and sparse biomass volumes as shelter or area for movement for different animal species.

Figure 6.

This figure describes step one (Loop2) of the generative process, in which variants of spatial organisation are iteratively generated for a given site based on (1) designers feedback expressed through generation criteria (amounts and types of volumes) and (2) computational feedback facilitated as evaluation of spatial constraints between the individual volume, based on the generation criteria.

Figure 6.

This figure describes step one (Loop2) of the generative process, in which variants of spatial organisation are iteratively generated for a given site based on (1) designers feedback expressed through generation criteria (amounts and types of volumes) and (2) computational feedback facilitated as evaluation of spatial constraints between the individual volume, based on the generation criteria.

Figure 7.

In the first step of the generative process (Loop 2) EIM Ontology 2 aids a rule-based process initial volume distributions are iteratively generated. Three types of cuboidal spatial volumes are distributed: (1) architectural volumes (grey), (2) soil volumes (brown), and (3) biomass volumes (green).

Figure 7.

In the first step of the generative process (Loop 2) EIM Ontology 2 aids a rule-based process initial volume distributions are iteratively generated. Three types of cuboidal spatial volumes are distributed: (1) architectural volumes (grey), (2) soil volumes (brown), and (3) biomass volumes (green).

Figure 8.

This figure describes step two (Loop 3) of the generative process, in which variants of geometric articulation for a given site and / or building volume. The output of Loop 2 (spatial organisation) is used as input for step three in which EIM Ontology 3 aids the generation of variants of geometric articulation to accomplish desired levels of landscape connectivity.

Figure 8.

This figure describes step two (Loop 3) of the generative process, in which variants of geometric articulation for a given site and / or building volume. The output of Loop 2 (spatial organisation) is used as input for step three in which EIM Ontology 3 aids the generation of variants of geometric articulation to accomplish desired levels of landscape connectivity.

As described in

Section 3.1.2 our approach to generating geometry for urban and building form, is based on our concept of Urban LandForm. This necessitates a systematic way of defining and identifying terrain features, which can be based on geomorphometry [

56], which is the scientific analysis of land surface [

57]. Land surface is understood as continuous. General geomorphometry is used to analyze landforms that are “bound segments of a land surface and may be discontinuous” [

58]. Specific geomorphometry entails the analysis of geometric and topological traits of landforms [

59]. A clear definition and delineation of landforms can pose ontological challenges [

60]. However, geomorphometric parameters [

61] can describe the morphology of the land surface and geomorphons can be used to classify and map landform elements. Recent research outlined a “novel method for classification and mapping of landform elements […] based on the principle of pattern recognition”[

62]. Since various types of urban geometry are not included in the geomorphons we extended and adapted this method to the study and development of urban form understood as continuous terrain.

The main premise that guides the development of the

Topographic Pattern approach is the existing limitation of the

geomorphons approach related to their possible application for generation of fully 3D geometry, to enable the generation of landform now extended to Urban LandForm. Three properties of the

geomorphons are decisive in this regard. Firstly, geomorphons describe terrain surface in terms of

ternary patterns, consisting of a

central point and eight directly

neighboring points. Geomorphons encode the relative height difference between the

central point and eight

neighboring points, denoted with three symbols (+, - or 0). Since this notation refers to the relative height difference, no assumptions about the absolute vertical position of the points constituting the pattern can be made.

Figure 1 in Jasiewicz and Stepinski [

62] provides an intuitive description of this property. Secondly, the algorithmic definition of the geomorphons is intentionally constructed to accommodate for different sizes of the terrain features representing the same geomorphon. Therefore, the position of the nine points constituting the

ternary pattern is not fixed on the horizontal plane. The original geomorphon algorithm calculates nadir and zenith angles to derive the horizontal position of the eight neighbouring points. The original paper [ref] [

62], explains the concept of the zenith and nadir angles and demonstrates how four different geometries are representative of a

valley geomorphon. Finally, since the original geomorphons approach is based on a 2.5D terrain surface representation, it does not take into consideration surface thickness, surface discontinuity or undercuts, vertical surfaces and transitions between horizontal and vertical surfaces. Addressing these limitations required the development of an extended approach, that we refer to as

Topographic Patterns. Initially, four categories of Topographic Patterns were proposed. The first category was directly derived from the geomorphons approach and referred to as horizontal topographic patterns. The second category reapplies the logic of geomorphons to vertical surfaces. The third category facilitates the transition between vertical and horizontal surfaces and the fourth category represents undercut geometries.

Figure 9 describes the four groups of topographic patterns.

Although each group contains only ten individual patterns, the application of this computational logic is challenging. This is due to the fact that each of the geometric patterns is representative of a large group of ternary patterns. In the case of geomorphons, if we consider three possible signs (-, 0, +) and eight neighboring points in the pattern, all possible pattern combinations can be created by computing a cartesian product of this set, resulting in 6561 possible combinations. In the geomorphons approach, a combination of deduplication strategy and a lookup table was used to distill all possible configurations into the ten canonical geomorphons. In particular, the role of the lookup table was to classify the ternary patterns representing an imperfect valley and a perfect valley into a single “valley” geomorphon. For reference see

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 in Jasiewicz and Stepinski [

62]. The challenge for the

Topographic Patterns approach and UrbanLandForm geometry generation is twofold. Firstly, the proposed approach needs to facilitate absolute vertical position of the points constituting the

Topographic Pattern, instead of the relative height difference denoted within the geomorphons approach with the three symbols (-, 0, +). Because of this the amount of possible pattern combinations is much larger. Moreover, the lookup table strategy is only partially applicable, since the ternary patterns would yield different 3D geometries.

Based on the identified constraints, our current study addresses a subset of 3D geometries that can be derived from the Topographic Pattern approach. The presented experimental study is based on horizontal topographic patterns and fixed vertical positions of the eight neighboring points. We decided to investigate the affordances of the proposed approach, based on research-through-design inquiry, instead of the exhaustive evaluation of the computational approach followed by a feasibility evaluation. Since the overarching goal is the utility in the design process, this approach allows us to manage the complexity of the proposed Urban LandForm approach. At the same time, we are able to identify and proactively solve upcoming problems based on a reduced set of possible geometries.

The proposed ontology-aided design process is guided by the interaction between the designers and the ontology, to facilitate the geometric expression of the Urban LandForm (

Figure 10). This interaction facilitates the initial creation and iterative refinement of the spatial organization, expressed as the three types of volumes. Individual volumes are defined through their position and additional properties, both derived from the designer decisions and from inferred through the ontological reasoning. In the first case, designers can make explicit spatial decisions by positioning nodes in the translational process, such as a placement of an EcoNode. In the ontology-aided design process, node properties are mapped to the individual volumes and additional properties, such as the minimum solid content, required by the plant indicated through the designer, are inferred by the ontology. In Loop 3, geometric expressions of the design are created and this expression is informed by (1) volume properties defined in Loop 1 and (2) designers feedback informed by the achievement of the defined criteria i.e., key performance indicators. To facilitate the synergy between biodiversity and geodiversity discussed in

Section 3.1.2, we guide the process of geometry generation by incorporating designers’ interactive feedback on (1) the amount of soil and (2) geodiversity, while (3) assuring connectivity of the created surface with focus on landscape connectivity. Representative metrics are inferred by the ontology, based on the properties describing individual topographic patterns and the properties derived from the previous loops.

3.5. Validation of the Conceptual Framework

The overarching ambition of the ECOLOPES project is to develop a robust design approach together with a computational framework and workflow and related tools to practitioners, e.g., architects and planners. The validation of the overall approach has been led by another partner in the project consortium and will be published separately. Regarding the development of the conceptual approach to the early design of ecological building envelopes, as facilitated by the ontology-aided generative computational design process, we wanted to validate whether practitioners are able to adequately familiarise themselves with the principal approach in a reasonable amount of time in order then to work with it. To pursue this we considered master-level students who had already received basic training during their bachelor level studies, as representative young practitioners with limited practice experience. To provide the context for this we ran a series of seven one-semester long master-level studios.

The first two studios focused on design case 1 as described in

Section 3.2, namely the design of a kindergarten at the western perimeter of the city of Vienna, directly adjacent to Wienerwald and a Habitat 2000 nature preserve area. In this way students had access to information regarding the local plant and animal species pool via the cadaster website of the City of Vienna and other available sources. The third and fourth studio focused on a large inner urban redevelopment area in Vienna with some existing ecosystems. The fifth, sixth and seventh studio focused on the particular topics of human-nature interactions, soil bodies, and the natural hydrological cycle respectively, asking for the design of a plot with a visitor centre. Each studio commenced with two-week workshop on various topics including data collection on local plant and animal species; information on local soils; information or simulation of local climate; the hydrological cycle; the evolution of the river Danube; construction methods in landscape engineering and landscape architecture; calculating ratios of architecture, biomass, and soil volumes of current state-of-the-art green buildings; etc. In parallel various Geographic Information Systems tools for analysis were introduced, to enhance the skill set in generating relevant datasets on local climate, water run off, terrain form, etc. This phase served to ground the design work in accumulated knowledge and skills. During the following 14 weeks projects were developed that were closely supervised by the teaching staff, who also delivered themed lectures and seminars to support the design development of the projects. As described in section 2 on Materials and Methods, research-through-design methodology was applied. To support the students with necessary ecological knowledge, ecologists from within and from outside the research project consortium were invited to give feedback and required information to the students.

During the first two runs of the studio it became clear that students could not be expected to acquire the entire range of necessary knowledge and skills related to our approach to the early design stage of ecological building envelopes. To accomplish this a broader educational agenda and courses would be necessary. Nevertheless, students frequently excelled in the uptake of the principal approach and key concepts, as well as one or several specific aspects of the design process. The following examples show the way in which students focused on specific aspects that demonstrate their capacities to comprehend and instrumentalise these aspects within a feasible amount of time and effort.

During the first two runs the master-level ECOLOPES studio at the Research Department for Digital Architecture and Planning at TU Wien focused on the design of a kindergarten with an ecological building envelope including close integration with the site. The site for this project is located at the Western perimeter of the city of Vienna where the suburban fabric transitions into the Wienerwald and the Natura 2000 protected nature area. During this first run of the ECOLOPES studio focus was placed on a species-rich area to focus on (1) the interactions between the children in the kindergarten and the other species on site, (2) the types of provisions the selected species require, and (3) the development of conceptual and methodological approaches to evidence and data-driven multi-species design. Both presented projects made use of networks to describe and operate on relations between environmental conditions, plant species and their locations, animal species provisions, and human and plant and animal species interactions. Two conceptual and methodological developments were directly related to the ontology-aided generative computational design process (1) the dataset maps, which contains spatio-temporal and multi-domain data for the design process, and (2) the dataset networks, which describes relations between individual architectural and ecological items and which is used to initiate the design process by localising and correlating items described in the architectural and ecological design brief.

Master students Filip Larsen and Juliana Schuch focused primarily on the development of methodological approaches to data-driven multi-species design. In their project a series of environmental and topographical analyses resulted in the datasets

maps and

networks, and ways in which these datasets can be correlated and can cross-inform one another to subsequently inform the distribution of plant species or location of provisions for animals. The methodological development required the formulation of a rule-based system that resolves how different datasets can inform one another in a meaningful manner for the purpose of executing the

translational process, which initiates the

generative design process (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12).

Master student Victoria Nemeth focused primarily on the interactions between the children in the kindergarten and plant and animal species on site, and the types of provisions the selected species require. The project was developed through a detailed list of selected species, as well as the intended interactions between the kindergarten children and the selected species. This was followed by the development of a strategy for the distribution of plant species or provisions for animals, and describing the different provisions required by each selected species and defining measures to integrate these either in the envelope of the kindergarten or the surrounding site (

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15).

In its third and forth run the master-level ECOLOPES studio focused on the centrally located urban development area Nordbahnhof Freie Mitte in Vienna. This area, which was a former major rail yard, features several ecosystems. The selected project example is for design Case 2, the design of an individual building for which all constraints, such as footprint, floor area ratio, maximum volume, and maximum height, etc. are already defined by an existing municipal master plan. Since the generic maximum allowed volume is already given by the masterplan, the task was to define the spatial organization and geometric articulation of the building, together with the placement of soil volumes, plant species, and accessibility and provisions for animal species. Master students Julien Doyen and Blandine Seguin first calculated the ratios of architectural, soil and biomass volumes for a series of current state-of-the-art green buildings to define a target ratio that goes significantly beyond current state of the art (

Figure 16). Subsequently, a series of green volume types were established (

Figure 17), solar exposure analysis of the surfaces of the allowed maximum volume was undertaken and the different types of green volumes were distributed within the overall allowed building volume, in accordance with their individual solar exposure requirements (

Figure 18). In the final step the connectivity between these green spaces was addressed, soil volumes were allocated, plants from a selected species list were placed, and accessibility and resources for animal species were defined (

Figure 19 and

Figure 20). This project followed closely the Urban LandForm approach for building design, thereby corresponding with the envisioned outcomes of Loop 3 of the generative process.

The examples of student work discussed above demonstrate that master-level architecture students are able to uptake the principal approach and key topics even though some of these challenge the currently prevailing understanding, modus operandi and related workflows on a fundamental level. In general, the topic seems to have resonated with students as a number of them, who participated in the studios, continued by focusing their master thesis on the ECOLOPES topic. One of the students who took the studio and did her master thesis on the topic recently commenced her PhD on an ECOLOPES related topic. This indicates that a younger generation of future architects are sincerely interested in more complex approaches to sustainability and the specific ECOLOPES topic and approach and are ready to invest time and commitment into interdisciplinary and sustainability related topics, even though this currently entails a significant extra effort.

4. Discussion

In this section we discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of the working hypotheses. As part of the reflection necessary further research directions and steps are indicated.

The principal approach and key concepts are currently developed to a level that facilitates a closely defined design approach, as shown in

Section 3.5. In general, the uptake of the principal approach, as well as key concepts and methodologies has been effective in the group of master-level students we worked with. However, further development and refinement is required to advance the approach.

Regarding the key concept of networks of items and relations and related methodology the master-level students demonstrated the capacity to uptake and utilize it effectively. However, the methodology - together with the associated computational components - needs to be advanced to become more instrumental in its application. This is by necessity an ongoing process since the composition of content, e.g., items and relations in networks, is always locally specific and related to the specifically selected design intentions and ecological strategies. Due to this, the network approach is always incomplete since there exists no finite set of relations that work for every condition and context. For the key components ontologies, including the knowledge graph, this implies that further content for logical reasoning needs to be developed continuously. What makes this a considerable challenge is that domain-specific or multi-domain worldviews might change, i.e., fostered by advancement of ecological approaches, which can entail significant changes of current content, e.g., redefinition of items and their relations. As such this entails ongoing conceptual and technical developments of content, and the computational processes and components that operate on network relations. This is in general the case with computational ontologies and can be addressed in various ways, i.e., by modularizing ontologies so that revisions or extensions can be apportioned in a more feasible manner. Further research is needed to establish the most promising way forward.

Regarding Urban LandForm several further developments are needed. First, it will be necessary to develop the geometric approach in such a manner that geometric articulation across several levels of hierarchy become possible. Since the underlying logic of Topographic Patterns derived from the geomorphons, is not bound to a specific geometric resolution, this is generally possible, but will require further research into how one terrain form can be nested within another without resulting in surface discontinuity in the process of form-generation in Loop 3. Second, an extensive library of relations between different terrain forms, their microclimate modulation capacities, as well as the capacities of microclimate to cater for biodiversity needs to be set up. This presents a considerable challenge for two reasons: (1) since research into the relation between geodiversity, microclimate variation, and biodiversity is fairly new and requires further development; (2) climate change impacts on how terrain forms in specific local contexts might result in or modulate specific microclimates. Addressing these aspects is a complex interdisciplinary undertaking that necessitates considerable research efforts.

Third, landscape dynamics need to be addressed and embedded within the overall approach to Urban LandForm. Wood and Handley explained that “[l]andscape dynamics refers to a process of landscape evolution, tracing the relationship between humankind and the natural environment. Its study is related to, but not coextensive with, land-use and land-cover change [

63], and views landscapes as holistic entities which reflect physical and cultural influence [

64,

65]. A systems perspective is helpful in understanding the nature of landscape dynamics whereby a process of feedback complements a linear relationship of inputs, process and outputs; inshort, a group of parts interacting in manifold processes [

66]” [

67]. Marcucci elaborated that “[l]

andscapes are constantly changing, both ecologically and culturally, and the vectors of change occur over many time scales. In order to plan landscapes, they must be understood within their spatial and temporal contexts. [...] the inevitable dynamism in a landscape requires planning to explain and to deal with change [...] planning has been slow to do this, in part because it is inadequately equipped to analyze both rapid change and gradual evolution. A landscape history exposes the evolutionary patterns of a specific landscape by revealing its ecological stages, cultural periods, and keystone processes. Such a history can be a valuable tool as it has the potential to improve description, prediction, and prescription in landscape planning” [

68]

. In principal terms landscape dynamics run counter to the perceived mandate for urban design and architecture to produce stable conditions. However, cities evolve over time and urban evolution and planning could be linked with landscape dynamics. This would necessitate commencing an entirely new field of research, with the intent to facilitate urban and landscape hybrid conditions, likely leading to novel forms of hybrid land use and related land cover arrangements that could be significantly more sustainable, thereby operating on enhancing the linkages between SDG 11 on “Sustainable Cities and Communities”, SDG 13 on “Climate Action”, SDG 15 on “Life on Land”, and SDG 6 on “Clean Water and Sanitation”. Forth, the question as to how to construct Urban LandForm requires addressing. In parallel to the research portrayed in this article we have made first steps into this direction by investigating construction approaches and methods in landscape architecture and landscape engineering as a way of engendering architecture and landscape architecture hybrid typologies that can incorporate much greater soil volume than current architectures and state-of-the-art green buildings. We term this approach

geomorphic tectonics [ref]. Initial research has commenced, but needs to be related to the three aforementioned points of developing the Urban LandForm approach.

Overall, the ECOLOPES research project, and more specifically the task of our team, has raised a series of fundamental questions that challenge significantly how urban planning and design and architecture are practised today. A lot more research and development efforts need to be invested to commence a trajectory that is as inclusive and holistic as described in the introduction. As part of this undertaking it is necessary to communicate and collaborate with people in governance, urban planners, and architects to generate interest in and awareness of the presented approach and collaborating with domain experts from Earth, environmental and life sciences towards a common goal. Finally, the general public needs to be addressed since it cannot be taken for granted that urban dwellers will see an expanded urban human-nature interface inherently as an advantage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H., A.A., J.T., and D.S.H.; methodology, M.H., A.A., J.T., and D.S.H; software, A.A. and J.T..; validation, M.H., A.A., J.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H., A.A., J.T., and D.S.H.; writing—review and editing, M.H., A.A., J.T., and D.S.H.; visualization, M.H., A.A., J.T., and D.S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is funded by the European Union Horizon 2020 Future and Emerging Technologies research project ECOLOPES: ECOlogical building enveLOPES (grant number: 964414).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions to this research made by our colleagues at TU Wien Christian Kern, Milica Vujovic, Tina Selami, and Navid Javan Shojamofrad. Furthermore, we acknowledge various members of the project consortium, including Mariasole Calbi from the University of Genoa and Victoria Culshaw from the Technical University Munich, for providing relevant datasets. Finally, we acknowledge valuable feedback on the student work by our colleagues Christian Kern, Milica Vujovic, Ferdinand Ludwig, Thomas Hauck, and Jeffrey Turko.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANT |

Actor Network Theory |

| CZ |

Critical Zone |

EIM

OWL |

ECOLOPES Information Model

Web Ontology Language |

RDB

RDF |

Relational Database

Resource Description Framework |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goal |

| SQL |

Structured Query Language |

References

- Author United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs – Sustainable Development – The 17 Goals (2024) Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed 10 February 2025).

- United Nations - Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (2024) Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/report/2024/SG-SDG-Progress-Report-2024-advanced-unedited-version.pdf (accessed 10 February 2025).

- Eurostat – How has the EU progressed towards the Sustainable Development Goals? Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/wdn-20210615-1 (accessed 10 February 2025).

- European Commission – The European Green Deal. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed 10 February 2025).

- European Environment Agency – Soil and United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/maps-and-charts/soil-and-united-nations-sustainable (accessed 10 February 2025).

- Hensel, M.; Sunguroğlu Hensel, D. Nature-integrated Design - Opportunity and Challenges. In Intelligent Buildings; Clements-Croome Ed.; ICE Publishing: London, UK, 2024; pp. 95-106. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. Basic Research Opportunities in Earth Science. The National Academies Press: Washington DC, USA, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, F.; Hensel, M.; Weisser, W.W. ECOLOPES Gebäudehüllen als biodiverse Lebensräume. In Bauen von morgen – Zukunftsthemen und Szenarien; Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung Eds.; Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung: Bonn, Germany, 2021; pp. 84–89.

- Perini, K.; Barath, S.; Canepa, M.; Hensel, M.; Mimet, A.; Mosca, F.; Roccotiello, E.; Salami, T.; Sunguroglu Hensel, D.; Tyc, J.; Selvan, S.U.; Vogler, V.; Weisser, W.W.. ECOLOPES: A multi-species design approach to building envelope design for regenerative urban ecosystems. In Proceedings Responsive Cities Design with Nature Symposium, Institute of Advanced Architecture Catalonia, Barcelona, Spain, Date of Conference (11-12 November 2021).

- Weisser, W.; Hensel, M.; Barath, S.; Culshaw, V.; Grobman, Y.J.; Hauck, T.E.; Joschinski, J.; Ludwig, F.; Mimet, A.; Perini, K.; Roccotiello, E.; Schloter, M.; Shwartz, A.; Sunguroğlu Hensel, D.; Vogler, V. Creating ecologically sound buildings by integrating ecology, architecture, and computational design. People & Nature 2022, 5(1), 4-20. [CrossRef]

- Calbi,M., Boenisch, G.; Boulangeat, I.; Bunker, D.; Catford, J.A.; Changenet, A.; Culshaw, V.; Dias, A.S.; Hauck, T.E.; Joschinski, J.; Kattge, J.; Mimet, A.; Pianta, M.; Poschlod, P.; Weisser, W.W.; Roccotiello E. A novel framework to generate plant functional groups for ecological modelling. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112370. [CrossRef]

- Joschinski, J.; Boulangeat, I.; Calbi, M.; Hauck, T.E.; Vogler, V.; Mimet, A. The ECOLOPES PLANT MODEL: a high-resolution model to simulate plant community dynamics in cities and other human-dominated and managed environments. bioRxiv. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Schröder, A.; Schloter, M.; Roccotiello, E.; Weisser, W.W.; Schulz, S. Improving ecosystem services of urban soils - how to manage the microbiome of Technosols?. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1460099. [CrossRef]

- Grobman, Y.J.; Weisser, W.W.; Shwartz, A.; Kozlovsky, R.; Ferdman, A.; Ludwig, F.; Hoek, T.; Perini, K.; Selvan, S.U.; Saroglu, S.; Barath, S.; Windorfer, L. Architectural Multispecies Building Design: concepts, challenges, and design process. Sustainability. 2024, 15(21), 15480. [CrossRef]

- Selvan, S.U.; Saroglou, S.T.; Joschinski, J.; Calbi, M.; Vogler, V.; Barath, S.; Grobman, Y.J. Towards multi-species building envelopes: A critical literature review of multi-criteria decision-making for design support. Building and Environment 2023, 231, 110006. [CrossRef]

- Mosca, F.; Calbi, M.; Roccotiello, E.; Perini, K. A computational approach to assess the effects of ecological building envelopes on outdoor thermal comfort. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 120, 106170. [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, J.W. Research Design, Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Method Approaches 4th Ed. Sage: Thousand Oaks CA, USA, 2014.

- Lenzholzer, S.; Duchhart, I.; van den Brink, A. The relationship between research and design. In Research in Landscape Architecture - Methods and Methodology; van den Brink, A.; Bruns, D.; Tobi, H.; Bell, S. Eds. Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2017; pp. 54–64.

- Stadt Wien. (2024). ViennaGIS - das Geografische Informationssystem der Stadt Wien—Daten und Nutzung. Available online: https://www.wien.gv.at/viennagis/ (accessed 28 October 2024).

- Lindsay, J. B. Whitebox GAT: A case study in geomorphometric analysis. Computers & Geosciences 2016, 95, 75–84. [CrossRef]

- Rittel, H. Der Planungsprocess als iterativer Vorgang von Varietätserzeugung und Varietätseinschränkung. In Arbeitsberichte zur Planungsmethodik - Entwurfsmethoden in der Bauplanung; Joedicke, J. Ed.; Karl Krämer Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 1970; pp. 17–31.

- Sunguroğlu Hensel, D.; Tyc, J.; Hensel, M. Data-driven Design for Architecture and Environment Integration: Convergence of data-integrated workflows for understanding and designing environments. Spool 2022, 9(1), 19-34. [CrossRef]

- Law, J. Notes on the theory of the actor-network: ordering, strategy, and heterogeneity. Systems Practice 1992, 5, 379–393. [CrossRef]

- Dwiartama, A. and Rosin, C. Exploring agency beyond humans: the compatibility of Actor-Network Theory (ANT) and resilience thinking. Ecology & Society 2014, 19(3), 28. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, E. Community design and cultures in cities. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990.

- Olivera, V.M.A.; Urban Morphology - An Introduction to the Study of the Physical Form of Cities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016.

- Rudnick, D., Ryan, S., Beier, S., Cushman, S.,Diefenbach, F., Epps, C., Gerber, L., Harrter, J., Jenness, J., Kintsch, J., Merenlender, A., Perkl, R., Preziosi, D., Trombulak, S. The role of landscape connectivity in planning and implementing conservation and restoration priorities. Issues in Ecology 2012, 16, 1–20.

- Costanza, J.K., Terando, A.J. Landscape connectivity planning for adaptation to future climate and land-use change. Curr Landscape Ecol Rep. 2019 ,4(1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Lookingbill, T.R., Minor, E.S., Mullis, C.S., Nunez-Mir, G.C., Johnson, P. Connectivity in the Urban Landscape (2015–2020): Who? Where? What? When? Why? and How?. Curr Landscape Ecol Rep 2022, 7, 1–14.. [CrossRef]

- Alberti, M.; Palkovac, E.P.; Des Roches, S.; De Meester, L.; Brans, K.I.; Govaert, L.; Grimm, N.B.; Harris, N.C.; Hendry, A.P.; Schell, C.J.; Szulkin, M.; Munshi-South, J.; Urban, M.C.; Verrelli, B.C. The complexity of urban eco-evolutionary dynamics. BioScience. 2020, 70(9), 772–93. [CrossRef]

- Zurlini, G.; Jones, K.B.; Riitters, K.H.; Li, B.L.; Petrosillo, I. Early warning signals of regime shifts from cross-scale connectivity of land-cover patterns. Ecol Indic. 2014, 45, 549–60. [CrossRef]

- Pelorosso, R.; Gobattoni, F.; Geri, F.; Monaco, R.; Leone, A. Evaluation of ecosystem services related to bio-energy landscape connectivity (BELC) for land use decision making across different planning scales. Ecol Indic. 2016, 61, 114–29. [CrossRef]

- Lookingbill, T.R., Minor, E.S., Mullis, C.S., Nunez-Mir, G.C., Johnson, P. Connectivity in the Urban Landscape (2015–2020): Who? Where? What? When? Why? and How?. Curr Landscape Ecol Rep 2022, 7, 1–14.. [CrossRef]

- Waldheim, C.. Landscape as Urbanism; Princeton University Press: Princeton NJ, USA, 2016.

- Allen, S. From the Biological to the Geological. In Landform Building; Allen, S.; McQuade, M. Eds.; Lars Müller: Baden, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 20–37.

- Gray, M. Geodiversity: Valuing and Conserving Abiotic Nature. Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2008.

- Gray, M. Geodiversity: developing the paradigm. Proceedings of the Geologists Association P 2004, 119(3-4), 287-298. [CrossRef]

- Vernham, G., Bailey, J.J., Chase, J.M., Hjort, J., Field, R., Schrodt, F. (2023) Understanding trait diversity: the role of geodiversity. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2023, 38(8), 736-748. [CrossRef]

- Alahuta, J.; Ala-Hulkko, T.; Tukiainen, H.; Purola, L.; Akujärvi, A.; Lampinen, R.; Hjort, J. The role of geodiversity in providing ecosystem services at broader scales. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 91, 47-56. [CrossRef]

- Brazier, V., Bruneau, P.M.C., Gordon, J.E., Rennie, A.F. Making Space for Nature in a Changing Climate: The Role of Geodiversity in Biodiversity Conservation’. Scot. Geogr. J. 2012, 128(3-4), 211-233. [CrossRef]

- Tukiainen, H., Kiuttu, M., Kalliola, R., Alahuta, J., and Hjort, J. Landforms contribute to plant biodiversity at alpha, beta, and gamma levels. J. Biogeogr. 2019, 46 (8), 1699-1710. [CrossRef]

- Tukiainen, H., Maliniemi, T., Alahuta, J., Hjort, J., Lindholm, M., Salminen, H., Snåre, H., Toivanen, M., Vilmi, A., and Heino, J., 2022. Quantifying alpha, beta and gamma geodiversity. Prog. Phys. Geog. 2022, 47 (1), 140-151. [CrossRef]

- Gruber, T. (2016). Ontology. In Encyclopedia of Database Systems; L. Liu, M. Özsu Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; pp. 1-3. [CrossRef]

- Gruber, T. R. A translation approach to portable ontology specifications. Knowledge Acquisition 1993, 5(2), 199–220. [CrossRef]