In this section, we define the geometric constructs.

2.1. PU-Patches and Developable V-Strips

Let

be the standard Euclidean scalar product on

with

its norm and × the cross product. In this paper, a curve is given by a smooth map

and a surface by a smooth patch

, both maps with values in

. The derivatives of

denoted by

give rise to the curvature and torsion of the curve, denoted by

. While the partial derivatives of

X denoted by

with its surface normal

N, give rise to the fundamental coefficients

and the Gaussian and Mean curvatures of the surface, denoted by

, (for detailed formulas, cf. [

12]). Recall that a patch is called conjugate if it satisfies

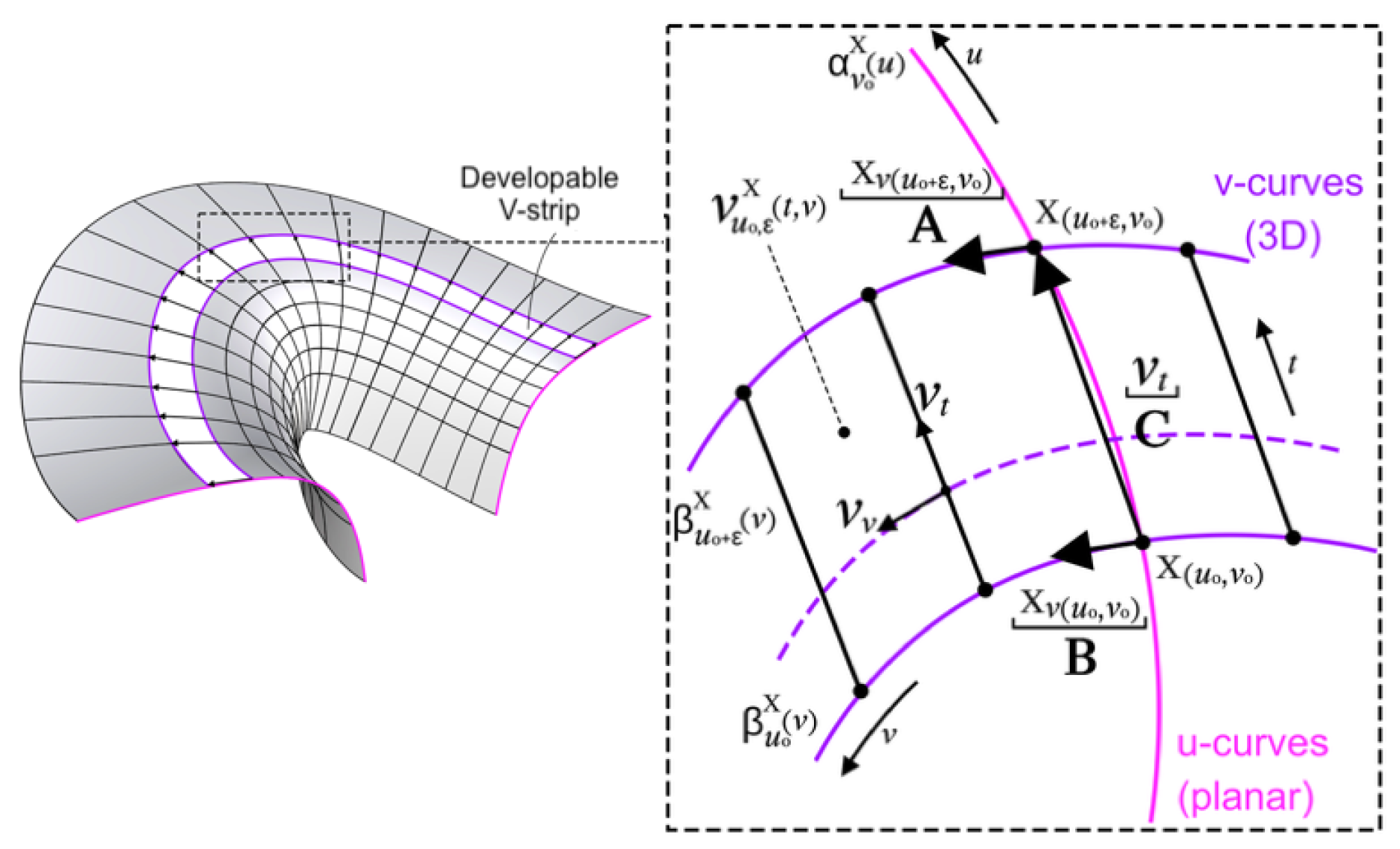

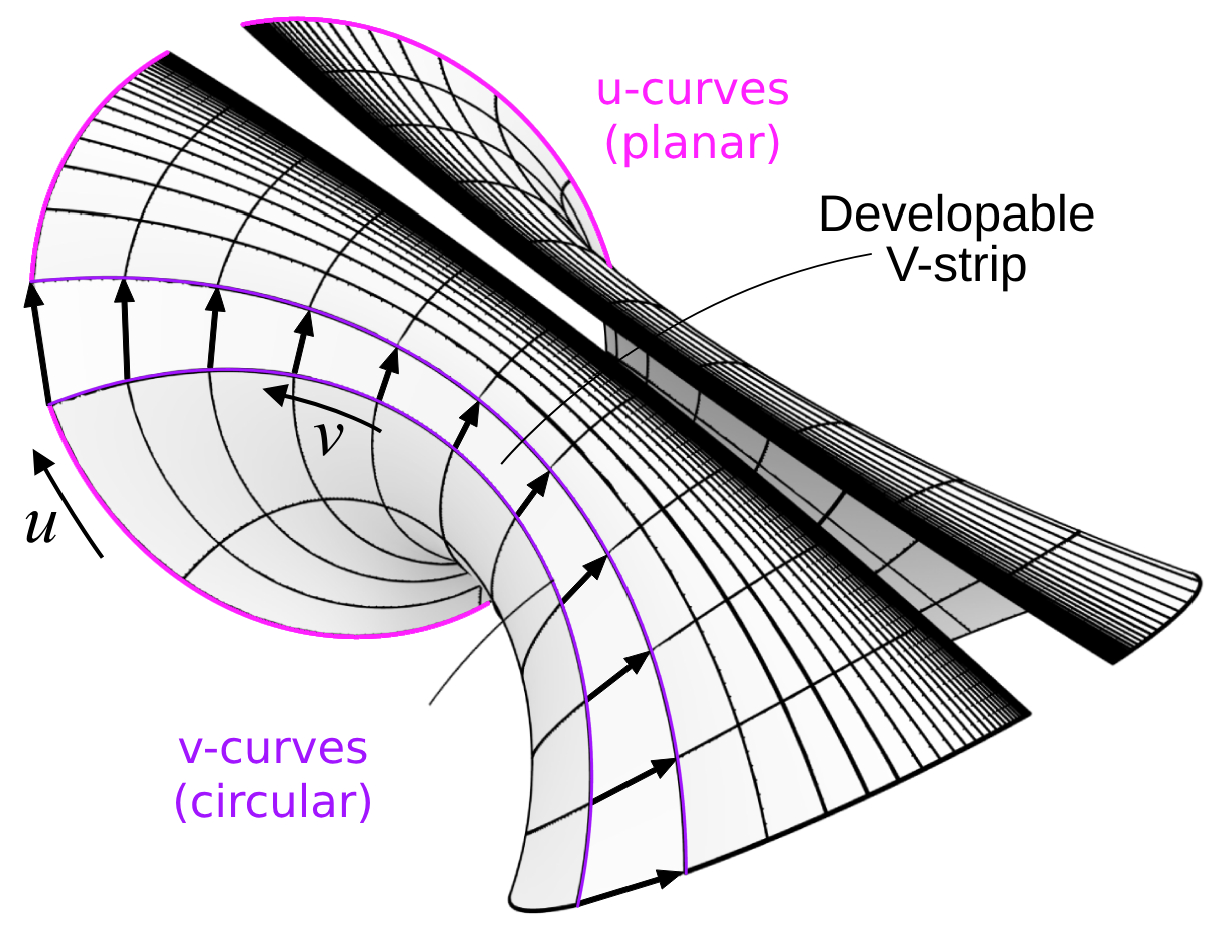

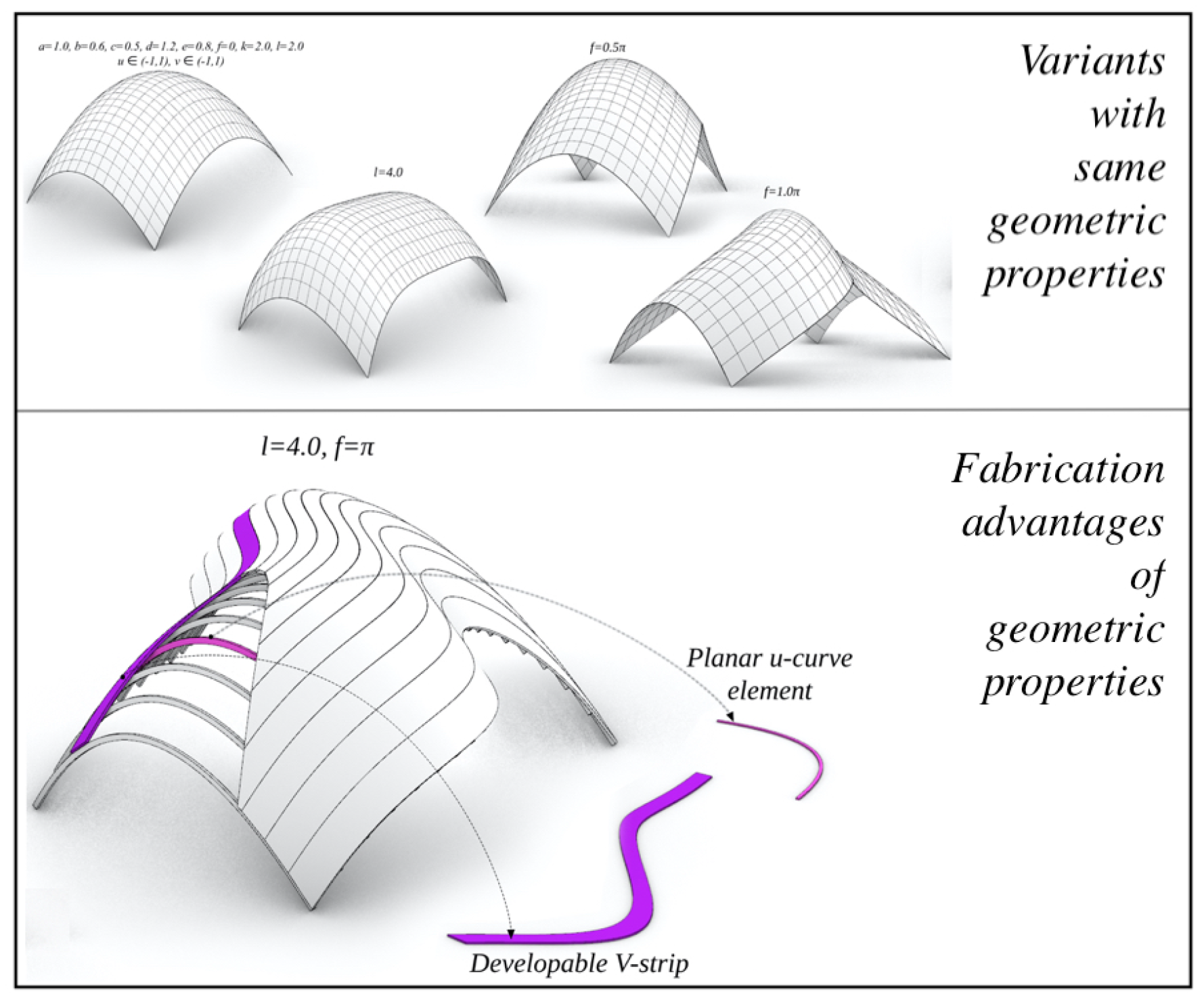

everywhere. Next, by a PU-patch, we mean one for which all its

u-curves are planar, i.e. having

everywhere and by a V-strip we mean the ruled surface constructed by the joins of two neighboring

v-curves:

for some fixed

. In particular, if these strips satisfy having

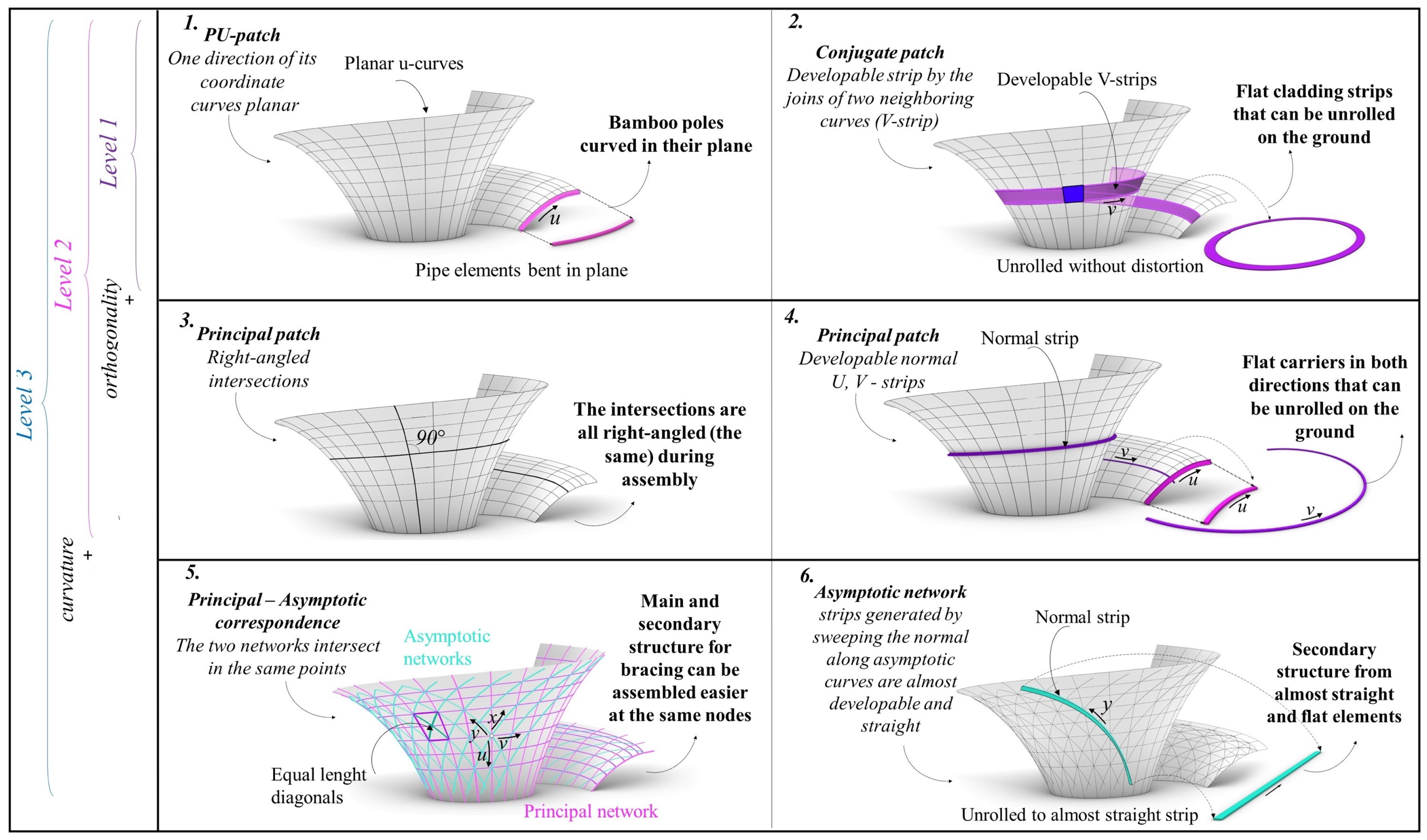

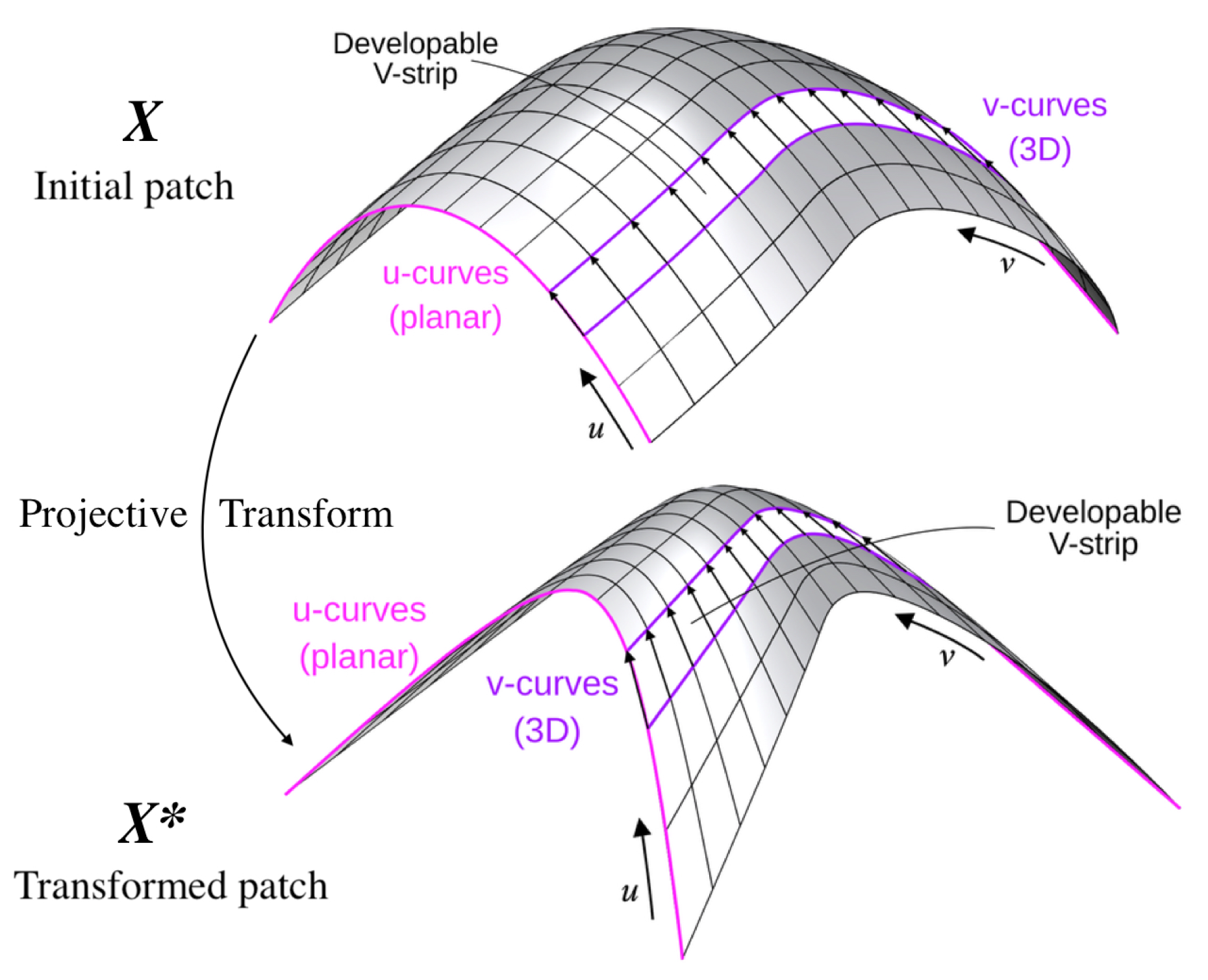

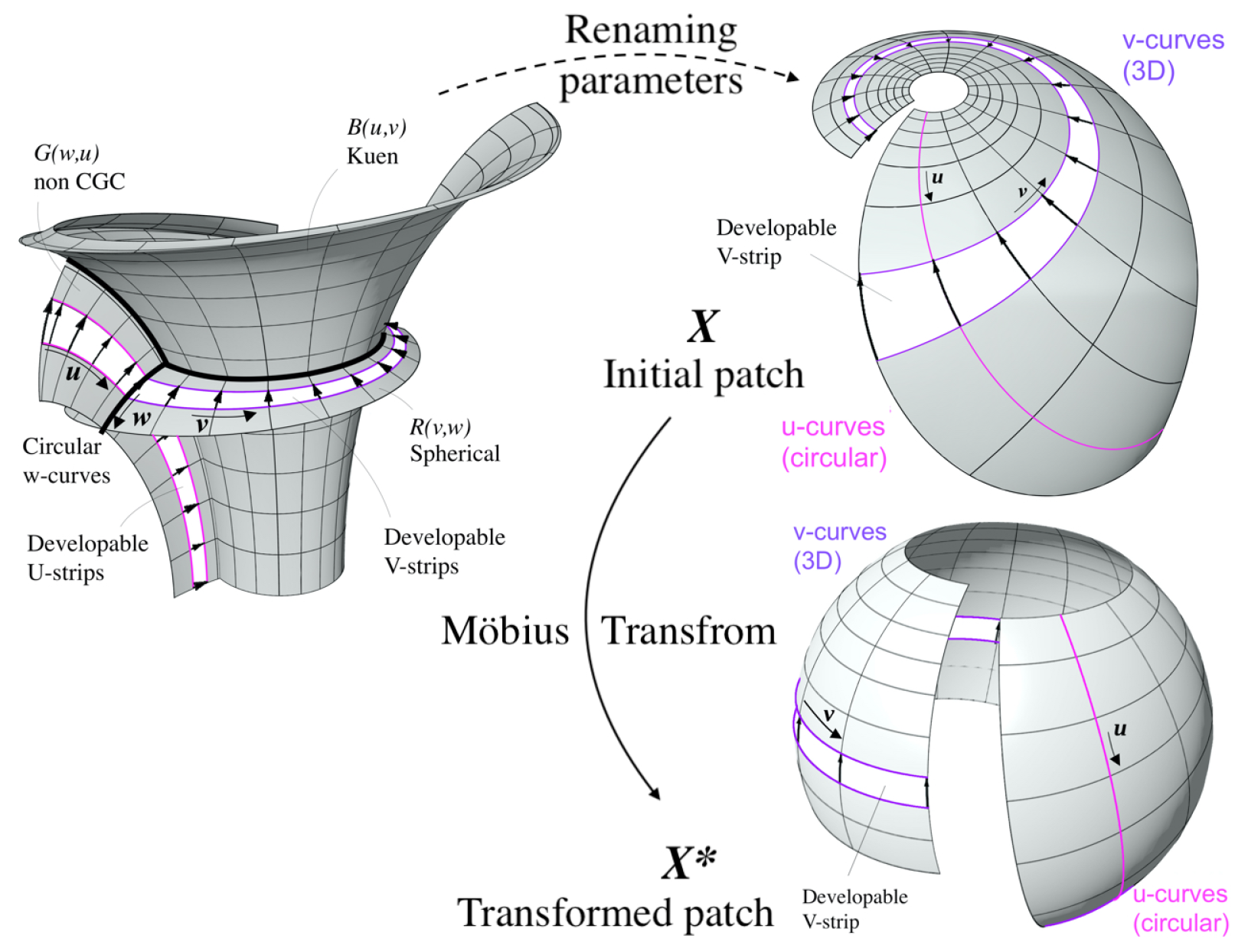

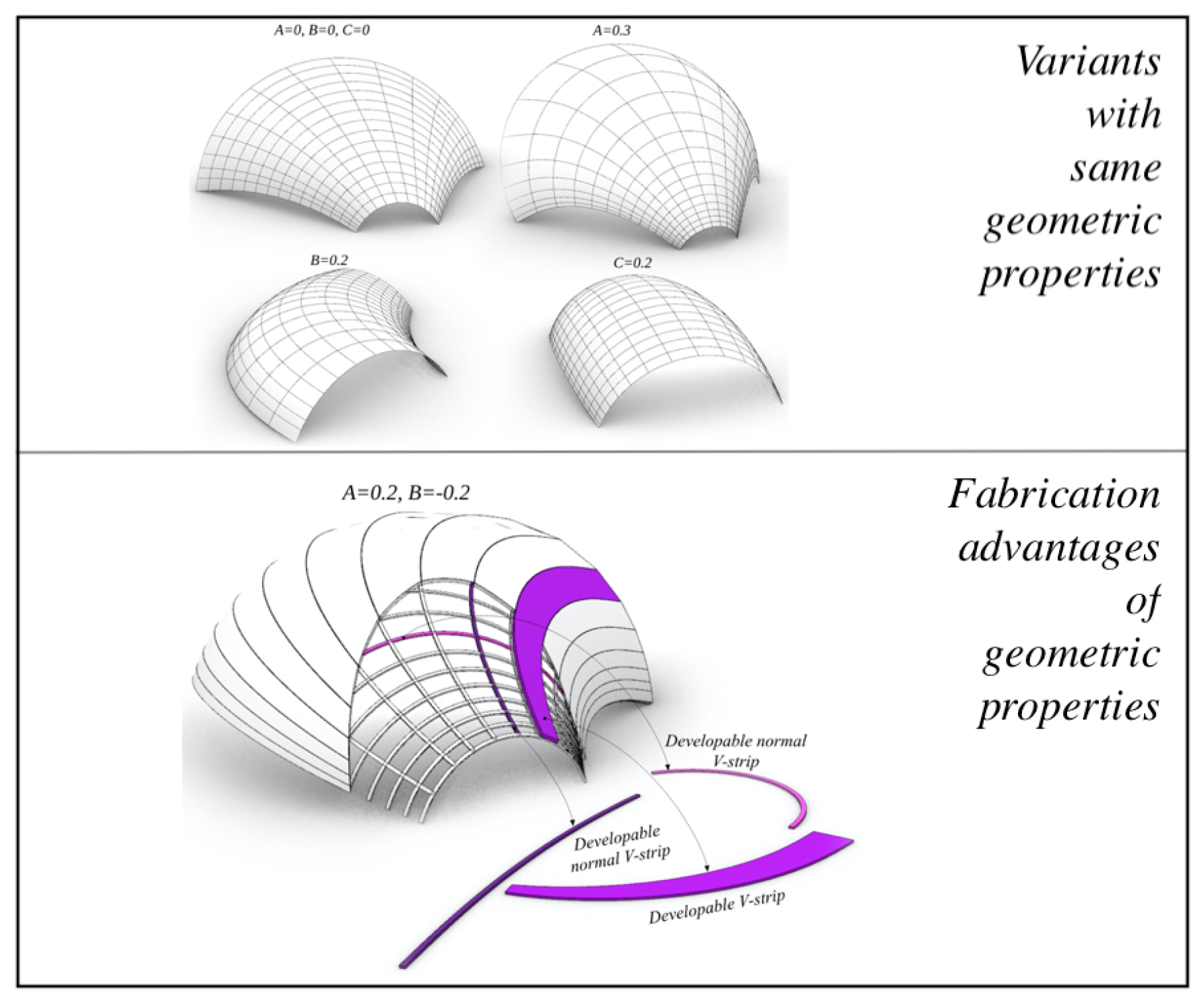

everywhere, then they are said to be developable. Clearly, the notions of a PV-patch and developable U-strip is analogous, hence will be omitted. Since we are interested in conjugate PU-patches with developable V-strips (because of their fabrication advantages, cf. Figure (

Figure 1)), it is then useful to have simple conditions to characterize them. Now, applying the formula for torsion on

u-curves of a patch

X and the formula for Gaussian curvature on V-strips, we are able to formulate the following characterization. A patch

X has:

for

,

and

for any

fixed and

. Recall that, if

X is conjugate, its V-strips are "quasi-developable", (

), since, a developable strip is the smooth analog of a sequence of PQ-mesh faces, cf. [

9,

13,

14,

15].

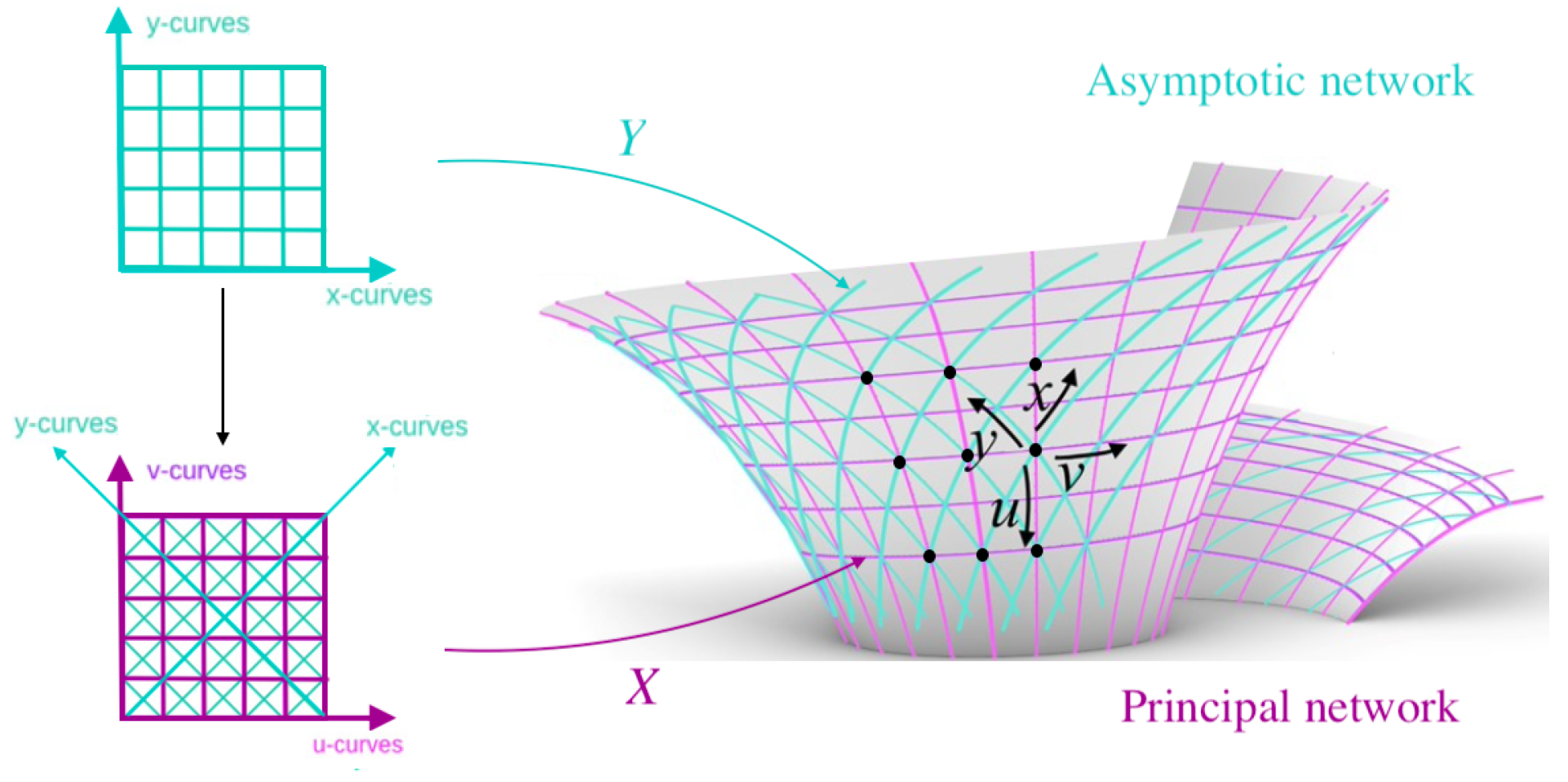

2.2. Geometric Constructs on Three Levels

We construct PU-patches with developable V-strips.

• Level 1 - Conjugate: The archetypal patch in this level, is the

Translation-type obtained by translating a planar generatrix curve

along a (spatial) directrix curve

, that is:

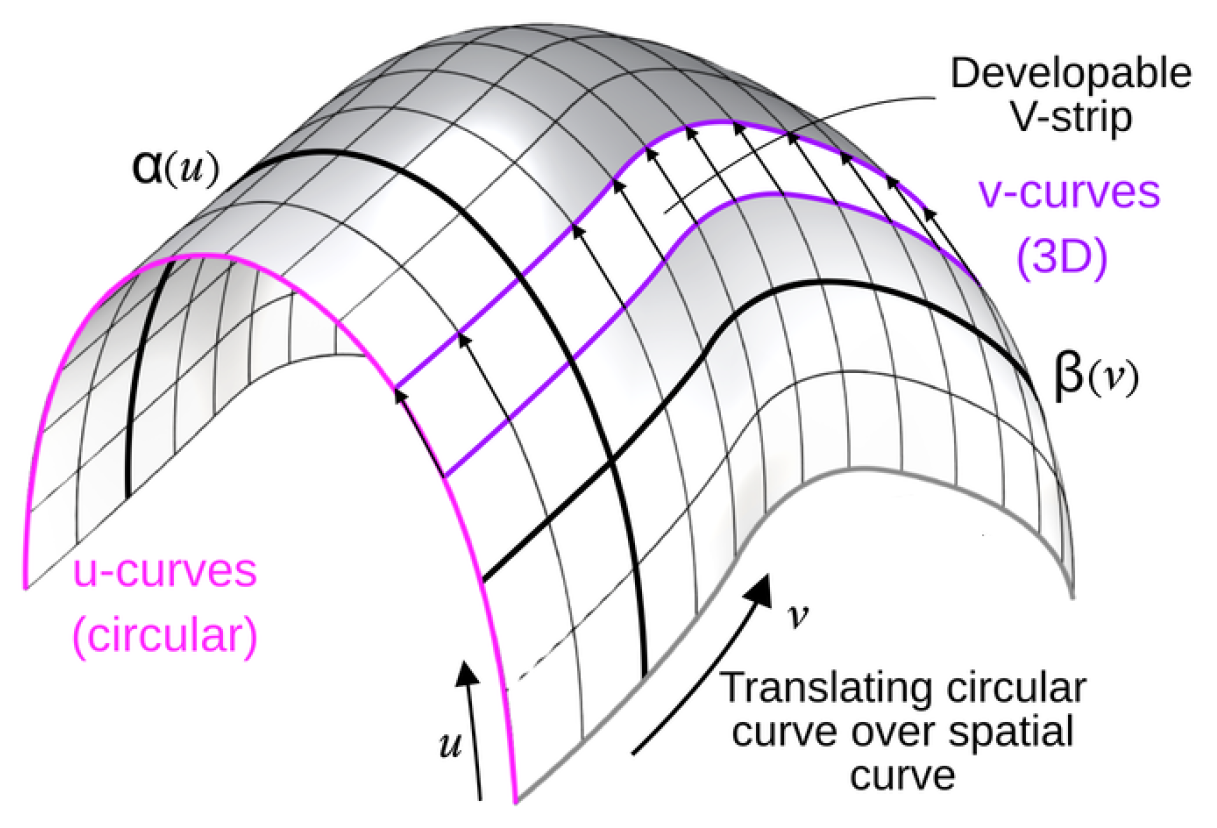

If the

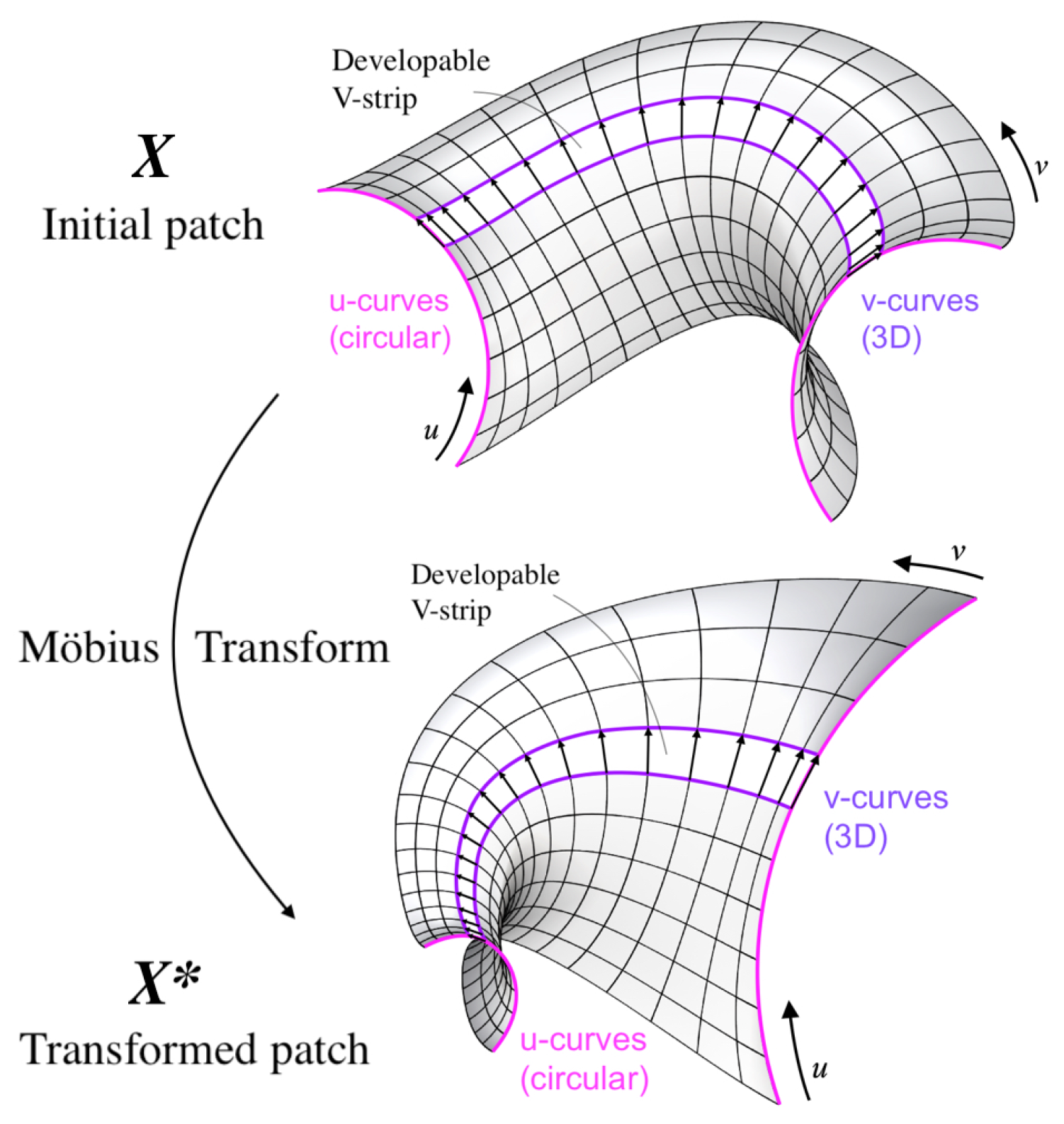

u-curves of a PU-patch are circular, then it is called a CU-patch, as seen in Figure (

Figure 3). Note that, the Translation-type (

3) is conjugate, satisfying Conditions (

2), hence, is PU with developable V-strips.

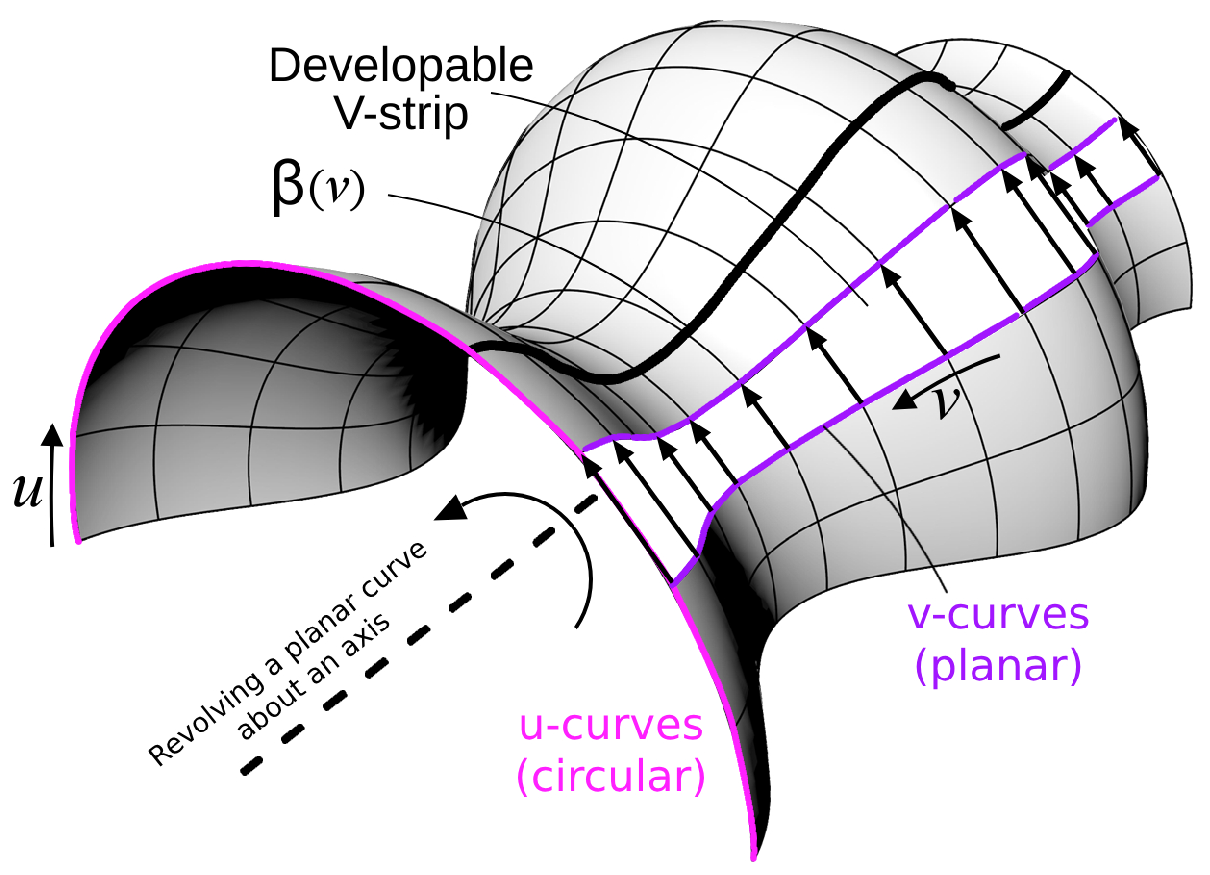

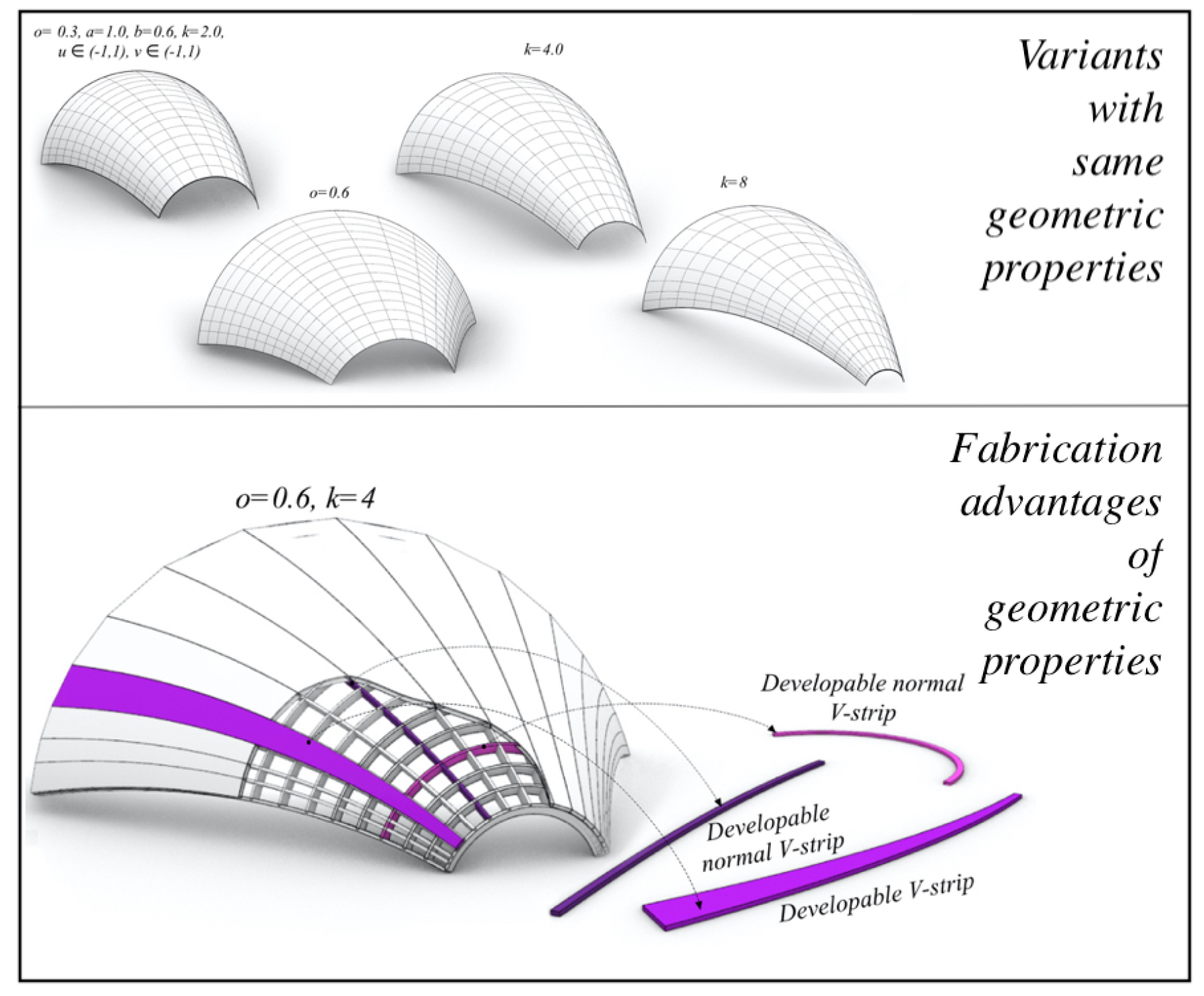

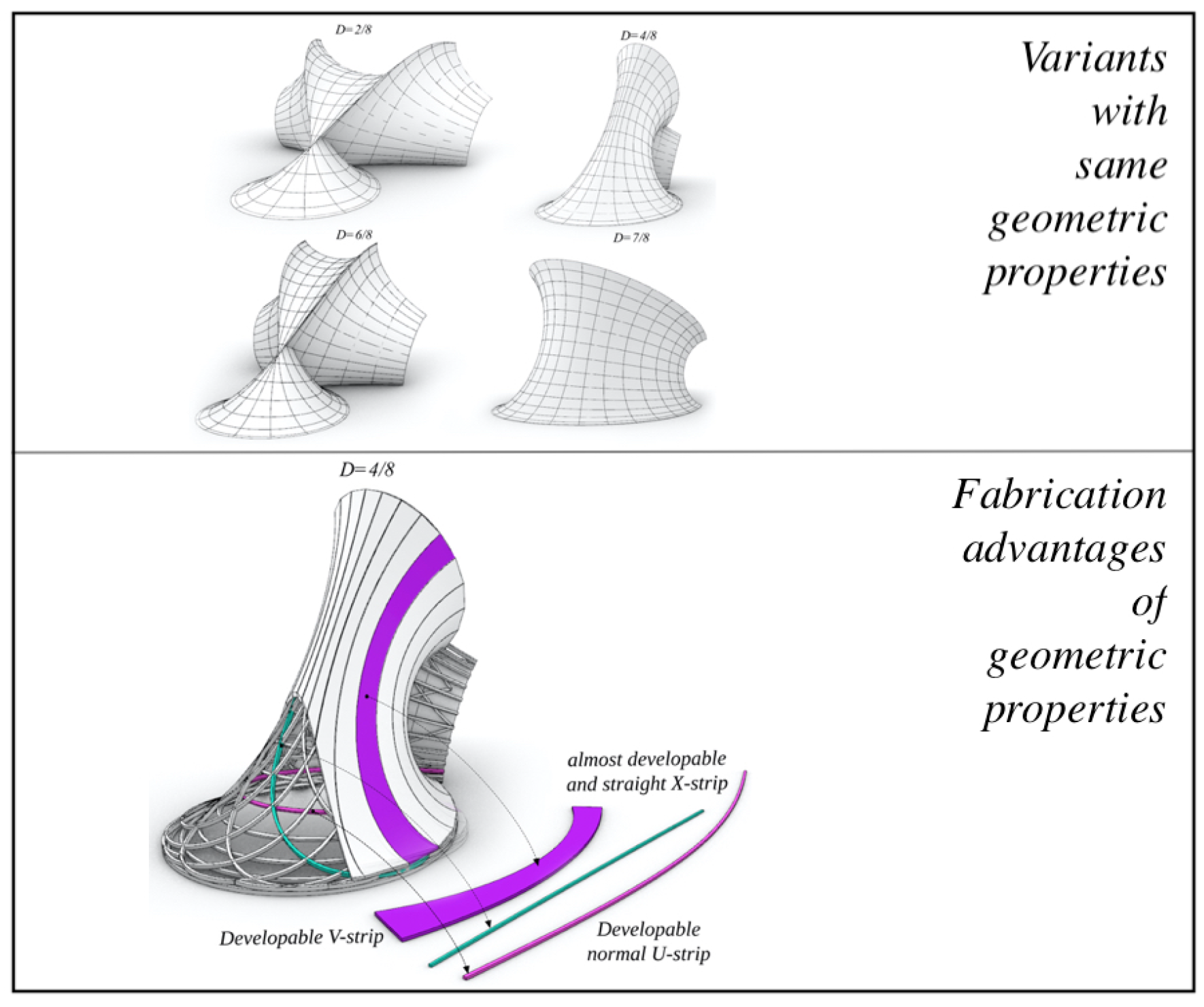

• Level 2 - Principal: The second level of geometric constraint on our conjugate PU-patch

X with developable V-strips, is requiring it to be orthogonal. This turns

X into a principal patch, meaning, its coordinate

-curves are curvature lines. This property adds further fabrication advantages, since any lath based on a strip obtained by sweeping the surface normal

N along any coordinate curve is developable, cf. Introduction

Section 1. The archetypal patch in this level, is the

Revolution-type obtained by revolving a planar curve

about an axis, that is:

This is clearly a CU-patch, as seen in Figure (

Figure 4). The second patch example in this level, is obtained as the envelope of spheres, known as Dupin cyclide. Geometrically, this involves two quadratic curves

called the focal directrices, on which the locus of centers of a family of spheres lie, cf. [

16]. Now, when

is an ellipse and

is a hyperbola, we obtain an ellipto-hyperbolic cyclide, while, when

are parabolas then we have a parabolic cyclide, as seen in Figure (

Figure 5). The

Cyclide-type is:

with

,

(for the first patch) and

(for the second patch). Finally, it is directly verified that any patch

X of Revolution-type (

4) or Cyclide-type (

5) has

everywhere and satisfies Conditions (

2). Hence, it is a principal PU-patch with developable V-strips.

The next patch on Level 2, is the

Monge-type given by the union of (2 by 2) parallel curves (i.e. having the same normal planes at corresponding points) and their orthogonal trajectories. In more accurate terms, it is given by a family of planar generatrix curves

drawn in the rectified normal planes along a spatial directrix curve

. The rectification means rotating the normal and binormal vectors

- generating the normal plane - of the directrix curve

, about its tangent by, the torsion angle

(integral of the torsion

), yielding

. More precisely:

Note that by construction the v-curves are parallel curves, hence all the V-strips are developable.

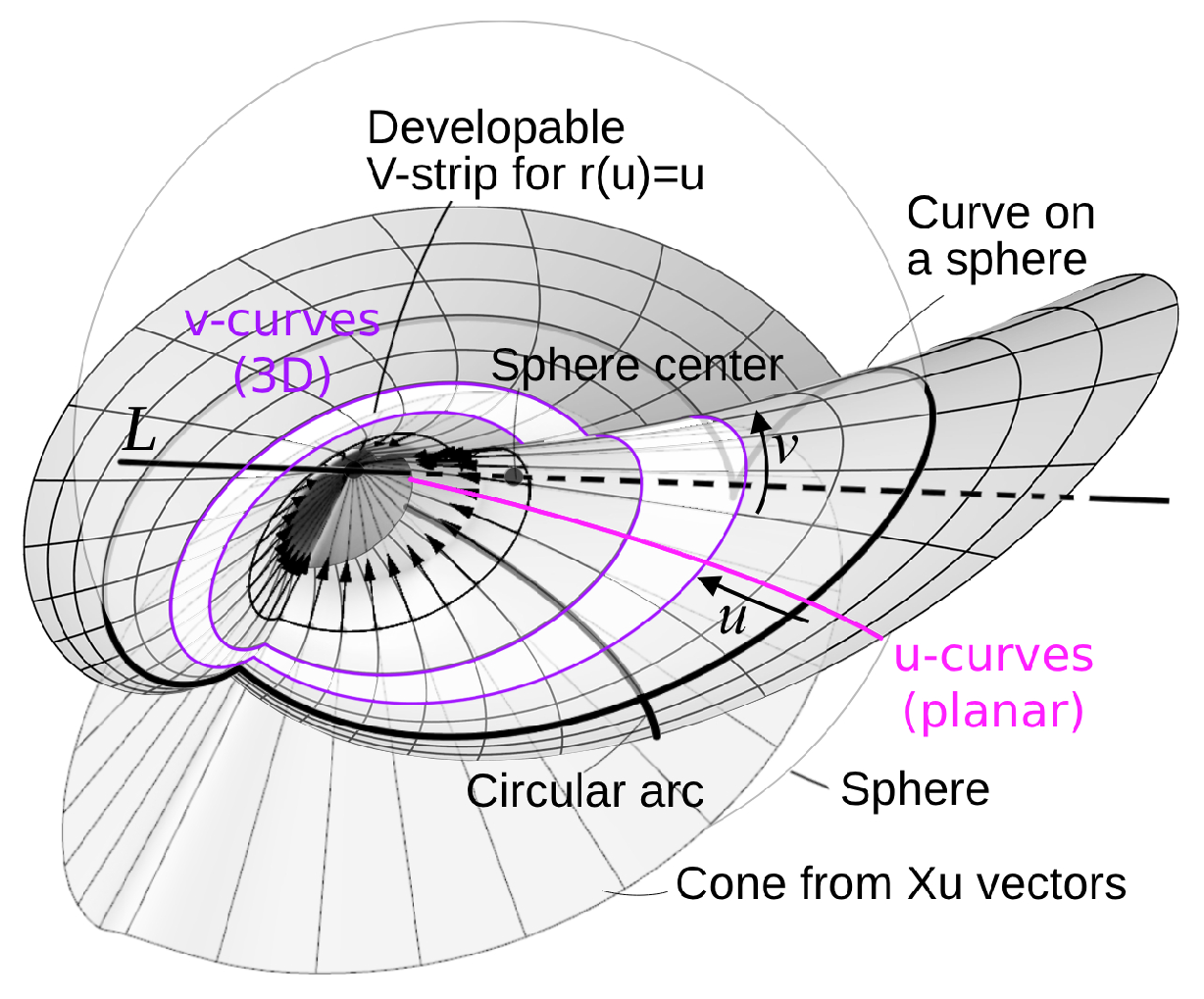

The following patch on level 2, is

Joachimsthal-type, it is given by a family of circular curves that are orthogonal trajectories to spherical curves, whose spheres’ centers lie on a straight line

L. More precisely, it is given by the parameterization:

Note that, the vectors

along any

v-curve, generate a cone whose vertex

o lies on the straight line

L. Moreover, the

v-curve is the intersection of the surface with a sphere centered at the point

o, and cutting the surface orthogonally, as seen in Figure (

Figure 7). We observe that any patch

X of Monge-type (

4) or Joachimsthal-type (

5) is a principal PU-patch, cf. [

17]. Moreover, if

X is any Monge-type or any Joachimsthal-type (with

) then, the Condition (

2)(2) is satisfied, turning the patch

X into a principal PU-patch with developable V-strips.

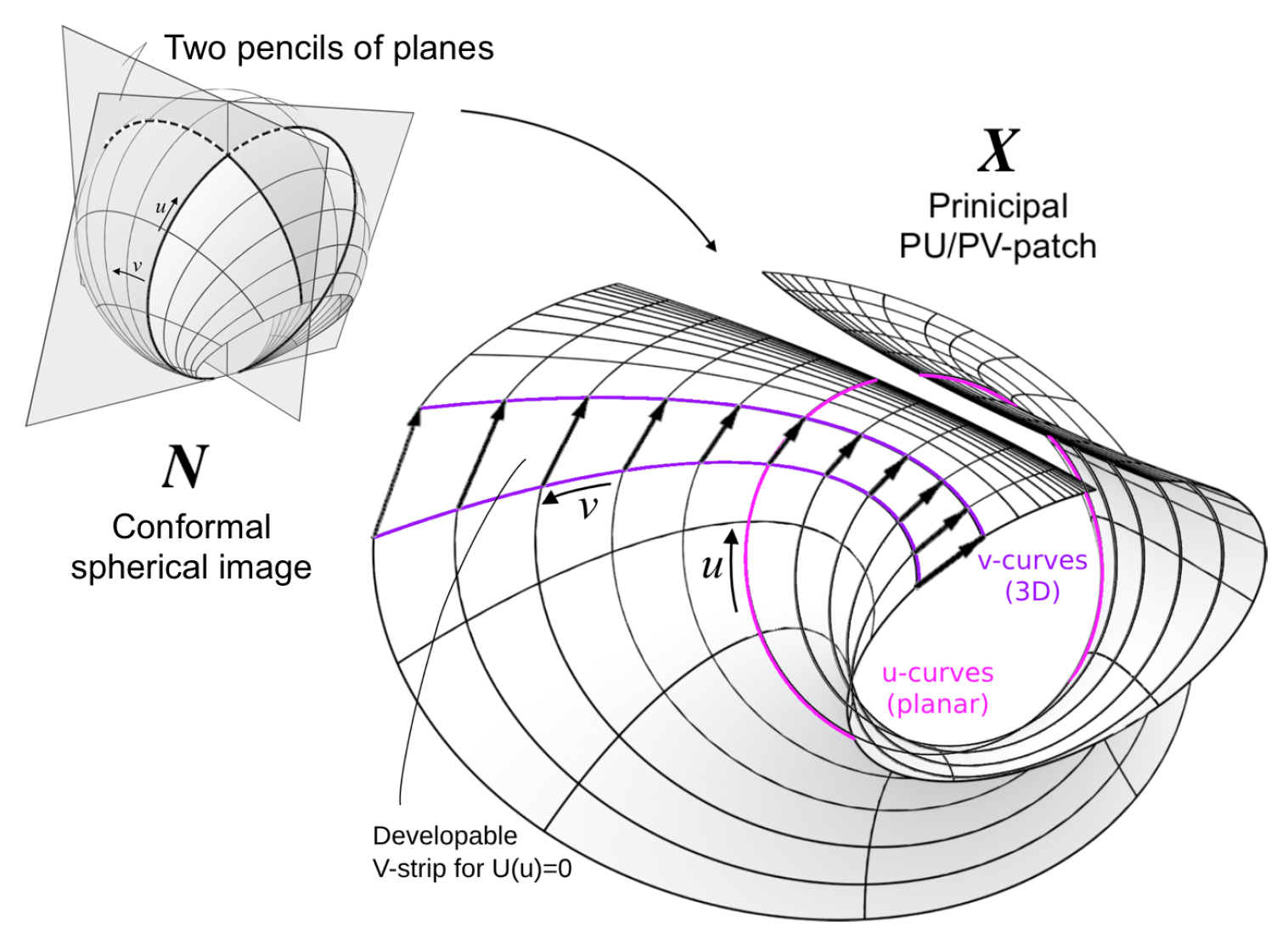

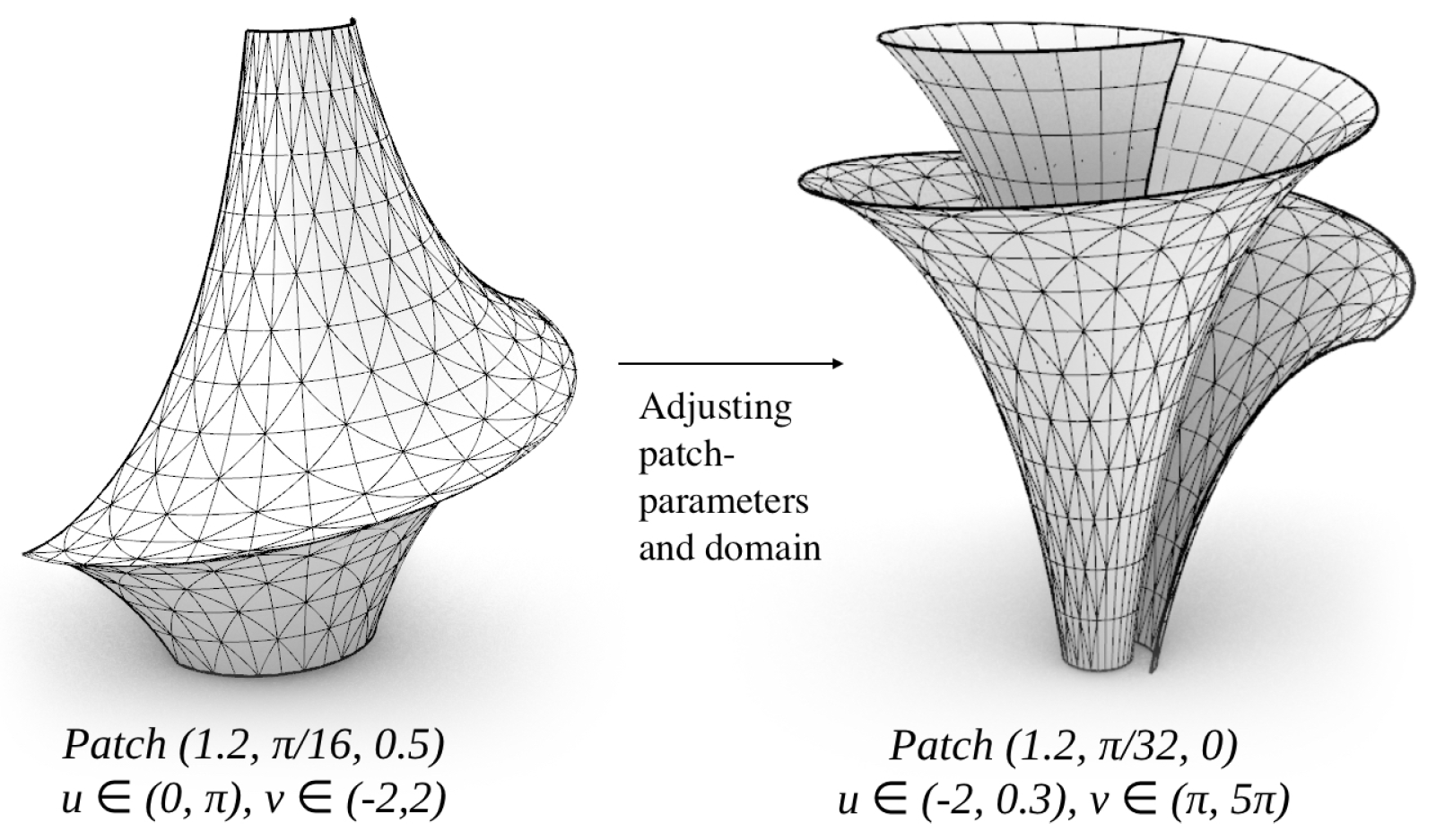

The final example we present in level 2, is what we will call the

Pencil-type. In this construction the desired PU-patch

X is obtained from its spherical image

N (i.e. surface normal), where the map

N parameterizes a system of orthogonal circular arcs on the unit sphere. The circular arcs are in fact the intersections of two pencils of planes with the sphere, hence the name “pencil-type”. We observe that the spherical patch

N arising in this way is conformal, with conformal factor

, that is, its fundamental coefficients satisfy

,

and the patch

X (from

N) is given by the formula:

where the

are functions

u alone, resp.

v alone. Note that, any patch

X of Pencil-type (

8) is principal with both its

-curves planar, in other words, it is a PU-patch and a PV-patch. Notice, if

then

-curves are circular, as seen in Figure (

Figure 8) and Condition (

2)(2) is satisfied, hence

X has developable V-strips. For a discrete construction of this, cf. [

4,

5].

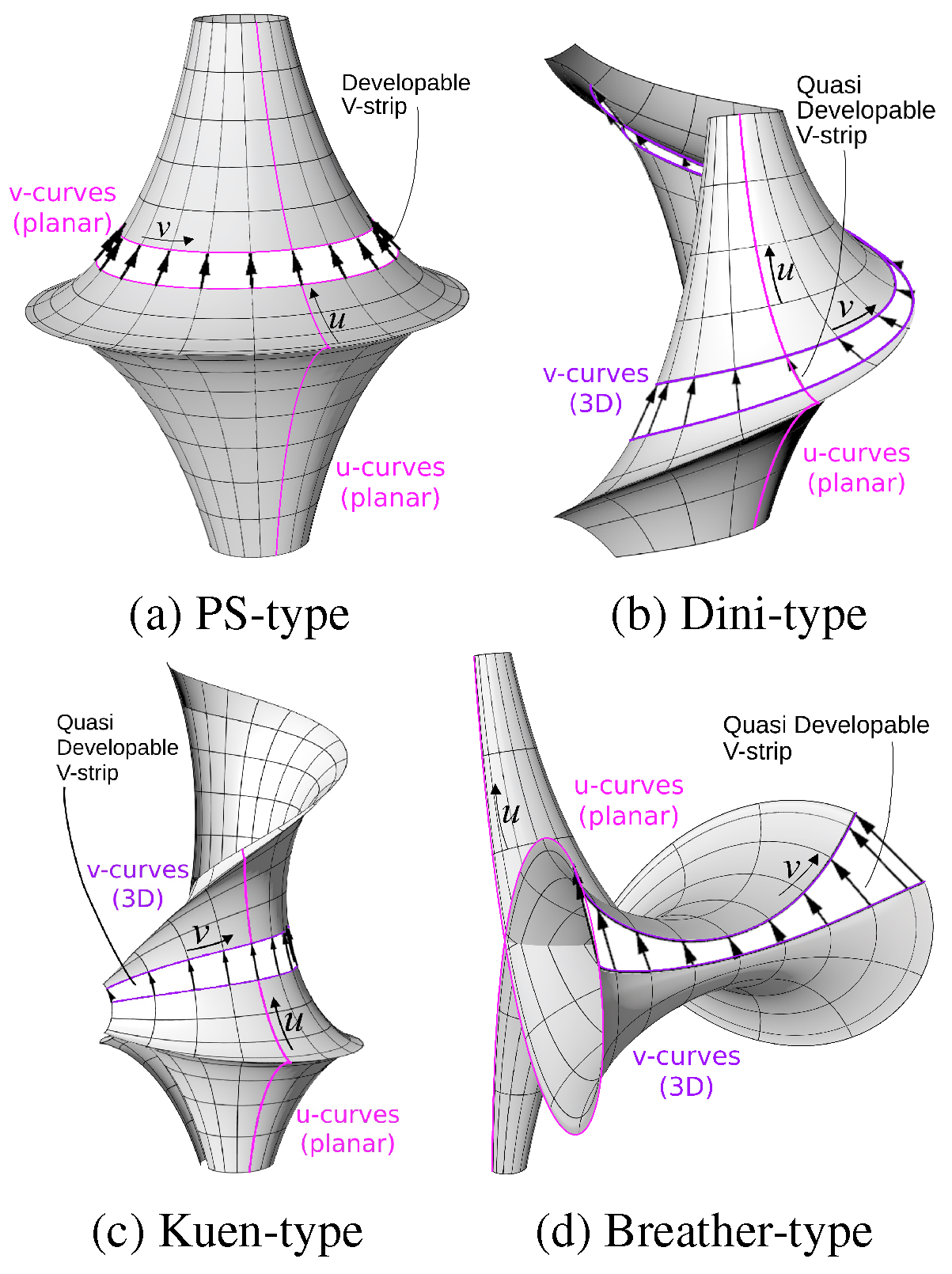

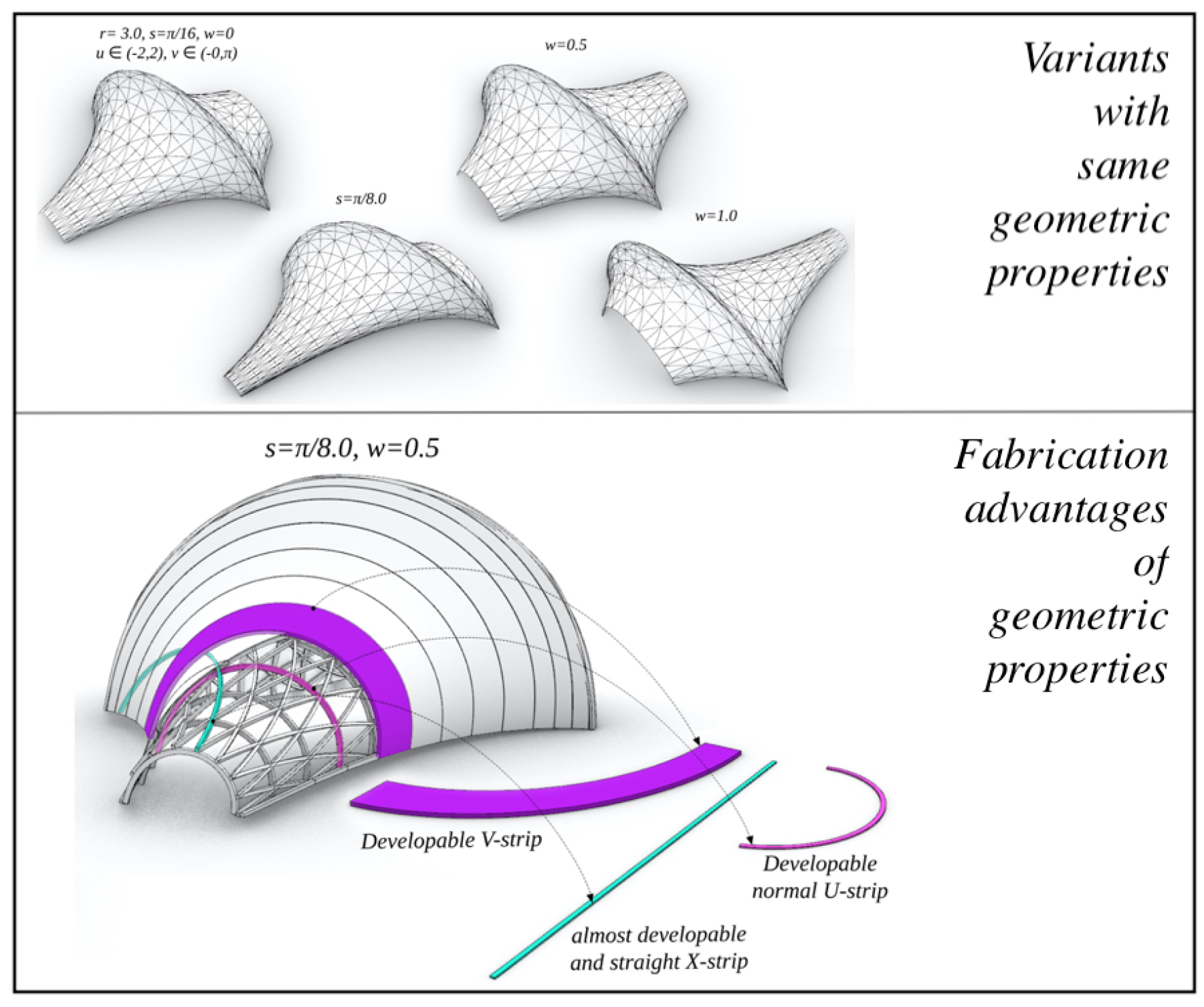

• Level 3 - Principal nCGC: The third level of geometric constraints is to require our PU-patches to be principal with nCGC

, with

. The construction is based on principal Tchebyshef patches of radius

and angle

(half the angle between asymptotic directions). The fundamental coefficients satisfy

,

,

and

,

with

satisfying the Sine-Gordon Equation:

. Moreover, a principal Tchebyshef patch

has the property of being associated to an asymptotic Tchebyshef patch

by the reparameterization

. We will consider the four types:

Pseudosphere-type (PS),

Dini-type,

Kuen-type, and

Breather-type, obtained by Equation (

11) (cf. [

18]) yielding:

Each of the types above, is a principal patch that satisfies Condition (

2)(1) making it a PU-patch, and, as a conjugate patch, it has quasi-developable V-strips.

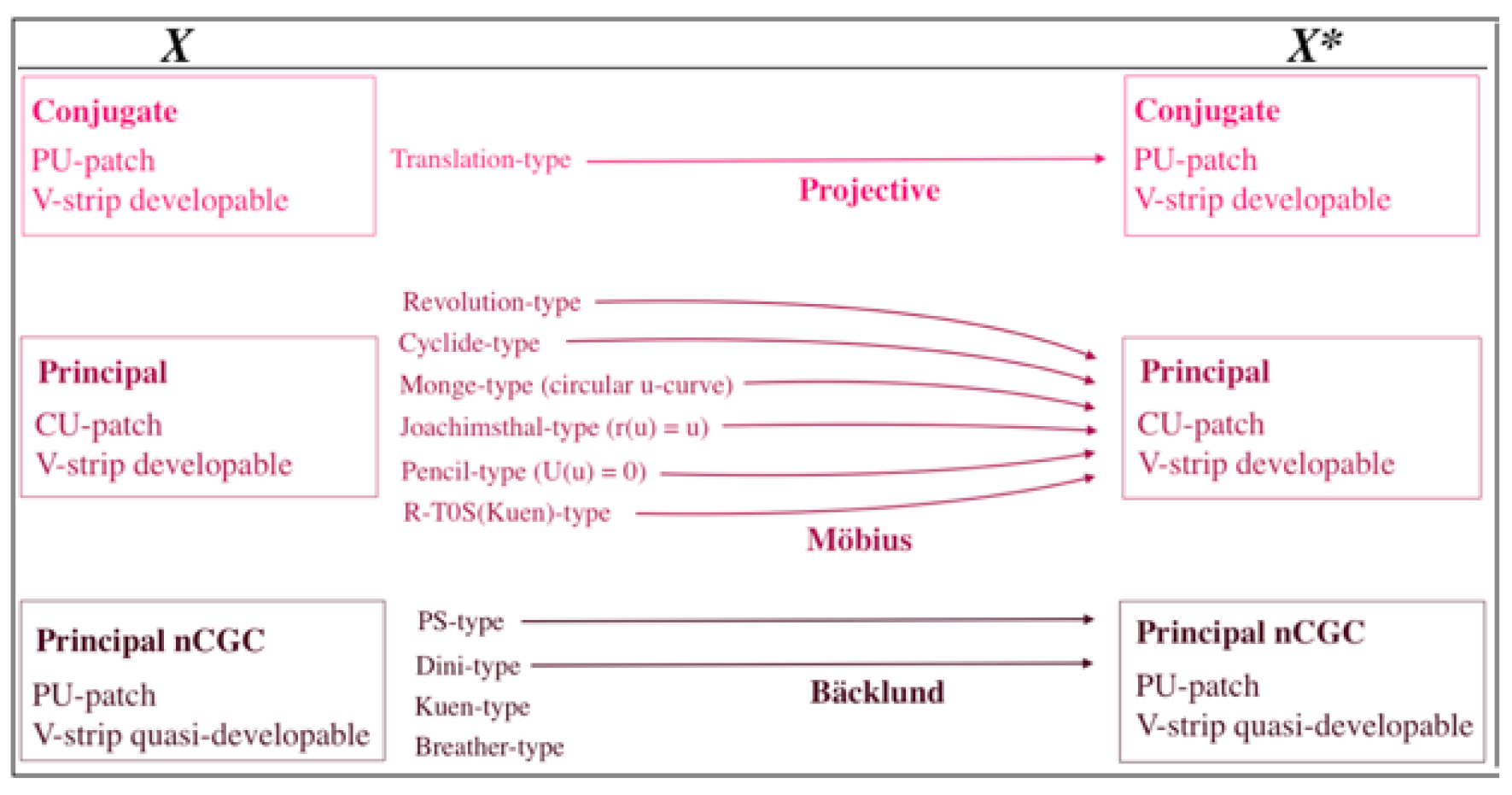

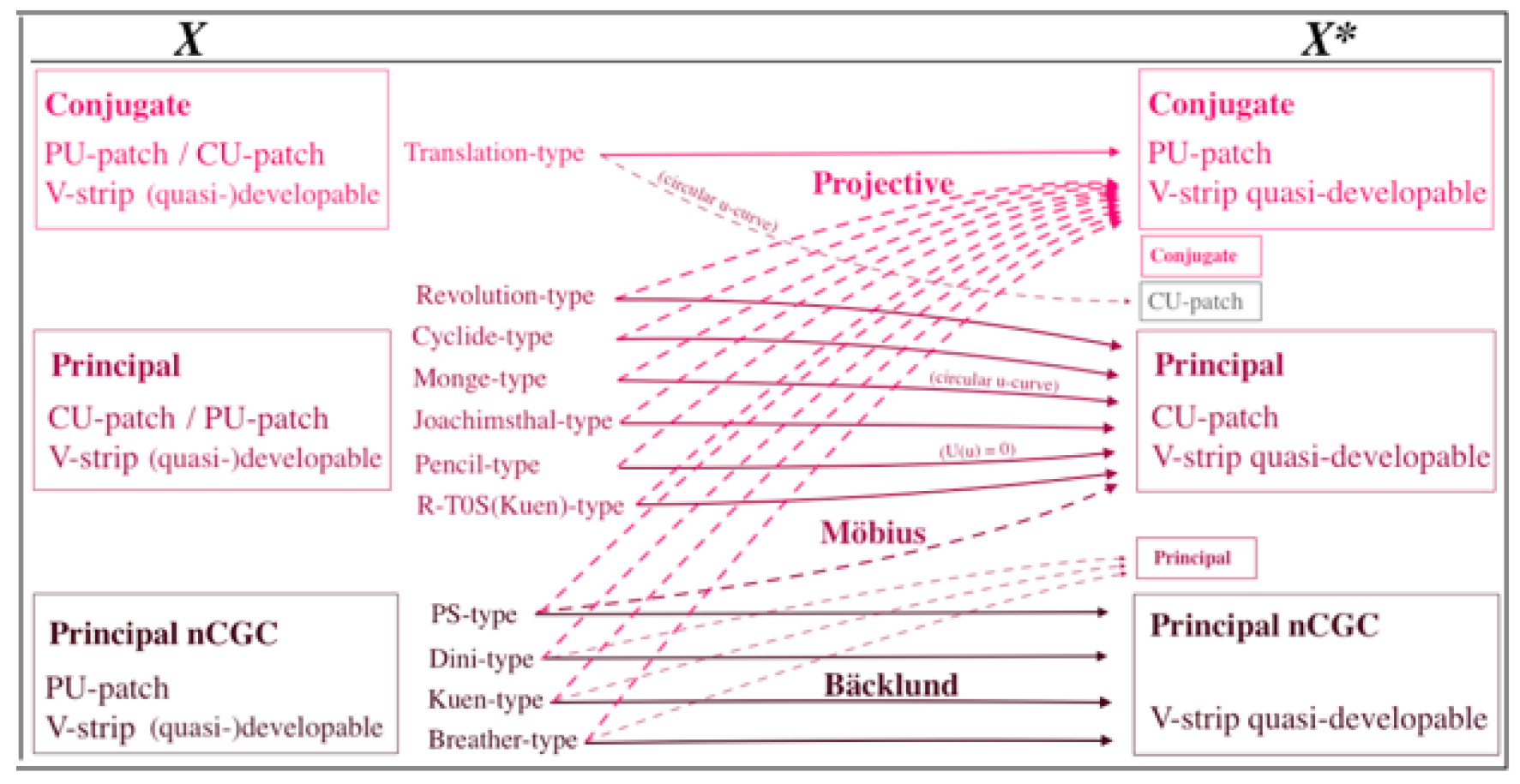

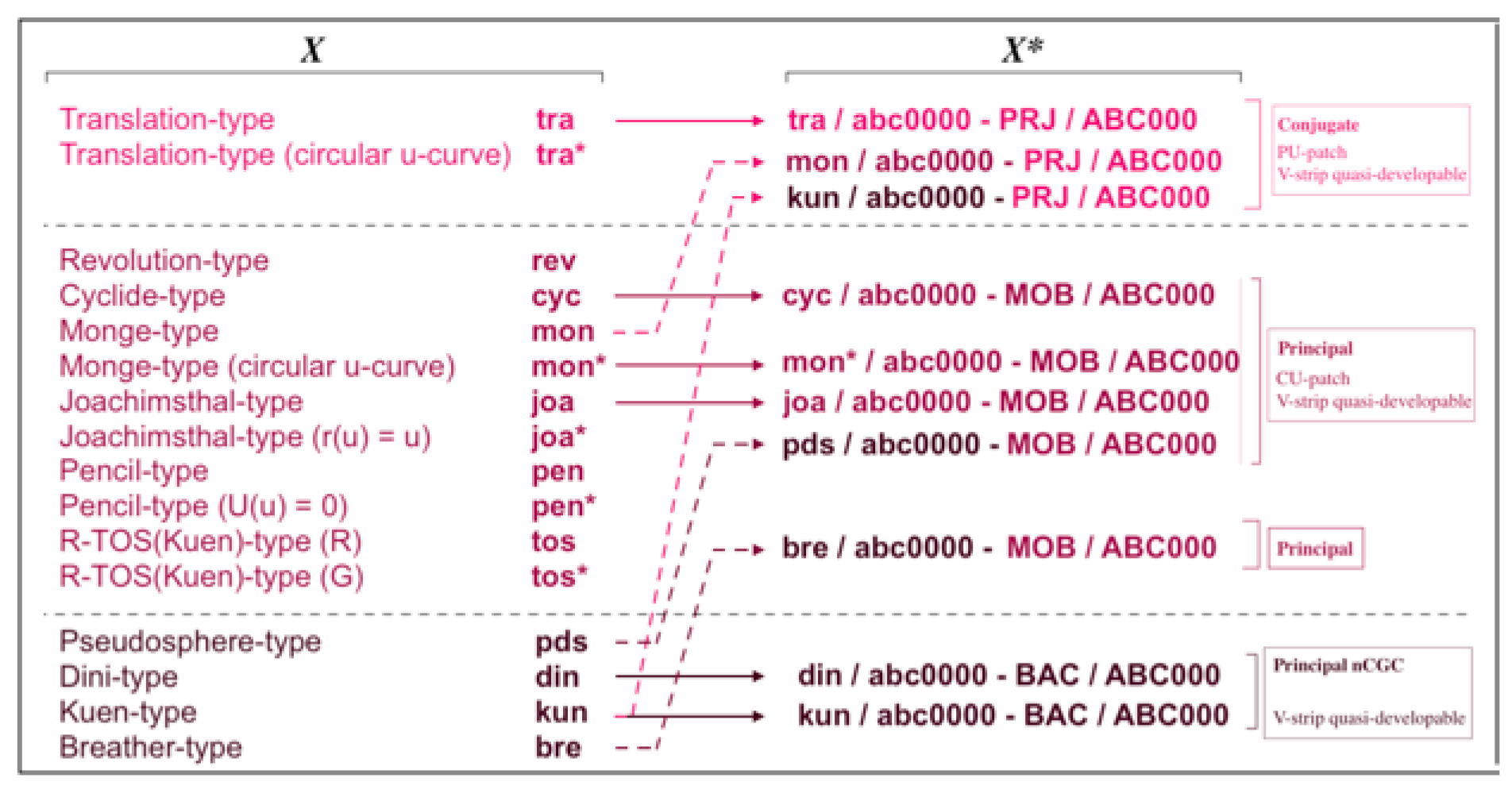

2.3. Geometric Transforms on Three Levels

We construct geometric transforms preserving the geometric properties of the patches constructed above on the three levels. More precisely, we have the corresponding scheme:

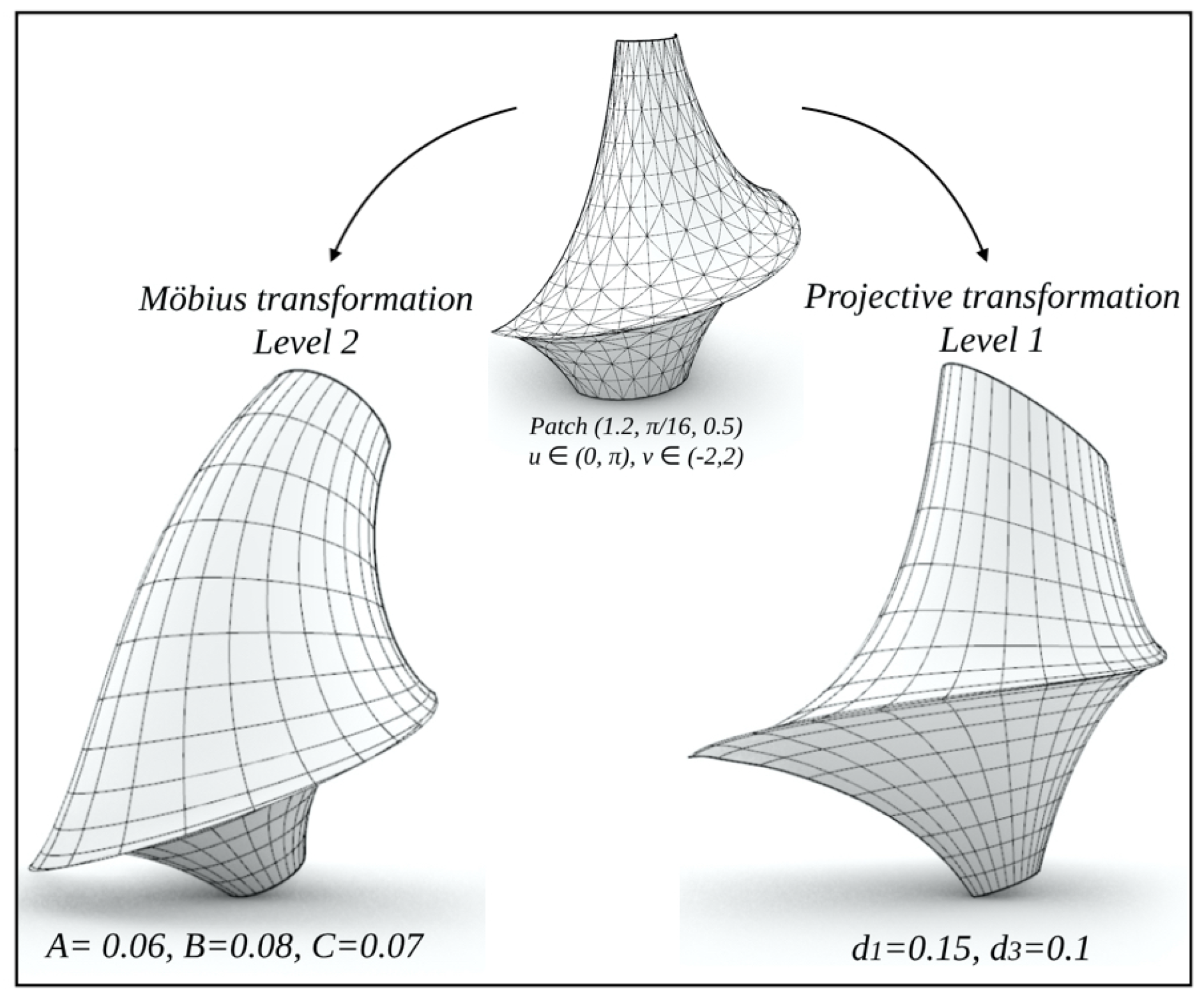

• Level 1 - Projective transform: This is a bijective mapping of the projective space

(seen as the lines through the origin in

), applied as multiplication by a regular (

)-matrix

on elements

of

. Upon seeing

as the affine subspace

, the projective transform of any patch

, as seen in Figure (

Figure 10), is given by:

Observe that, if the initial patch

X is a conjugate PU-patch, then its projective transform

will also be a conjugate PU-patch. This follows from the fact that, a projective transform preserves linear subspaces and conjugate patches, cf. [

17,

19]. Moreover, if the initial patch

X is of a Translation-type (

3), then its projective transform

will satisfy Condition (

2)(2), hence the developability of V-strips will be preserved as well.

• Level 2 - Möbius transform: This is a bijective mapping of the 3-sphere

(seen as the compactification of

), cf. [

20]. By restricting to

, a Möbius transform can be given by compositions of translations, homotheties (uniform scaling), linear-orthogonal maps (Euclidean motion) and inversions. In more accurate terms, a Möbius transform

of a patch

, as seen in Figure (

Figure 11), can thus be expressed by the formula:

Note that, if the initial patch

X is a principal CU-patch, then its Möbius transform

will also be a principal CU-patch. This follows from the fact that, a Möbius transform preserves circles and principal patches, cf. [

17,

19]. Furthermore, if we let in addition the initial patch

X to have developable V-strips and also be any of the above defined types (geometric constructs): Revolution-type (

4), Cyclide-type (

5), Monge-type (

6) (with

circular), Joachimsthal-type (

7) (with

), or Pencil-type (

8) (with

). It then follows that, its Möbius transform

will have developable V-strips as well. To see this, recall that developability is preserved by translation, homothety and linear-orthogonal maps. Thus, to conclude, we only need to verify that the inversion

satisfy Condition (

2)(2) in the stated types, which is indeed true.

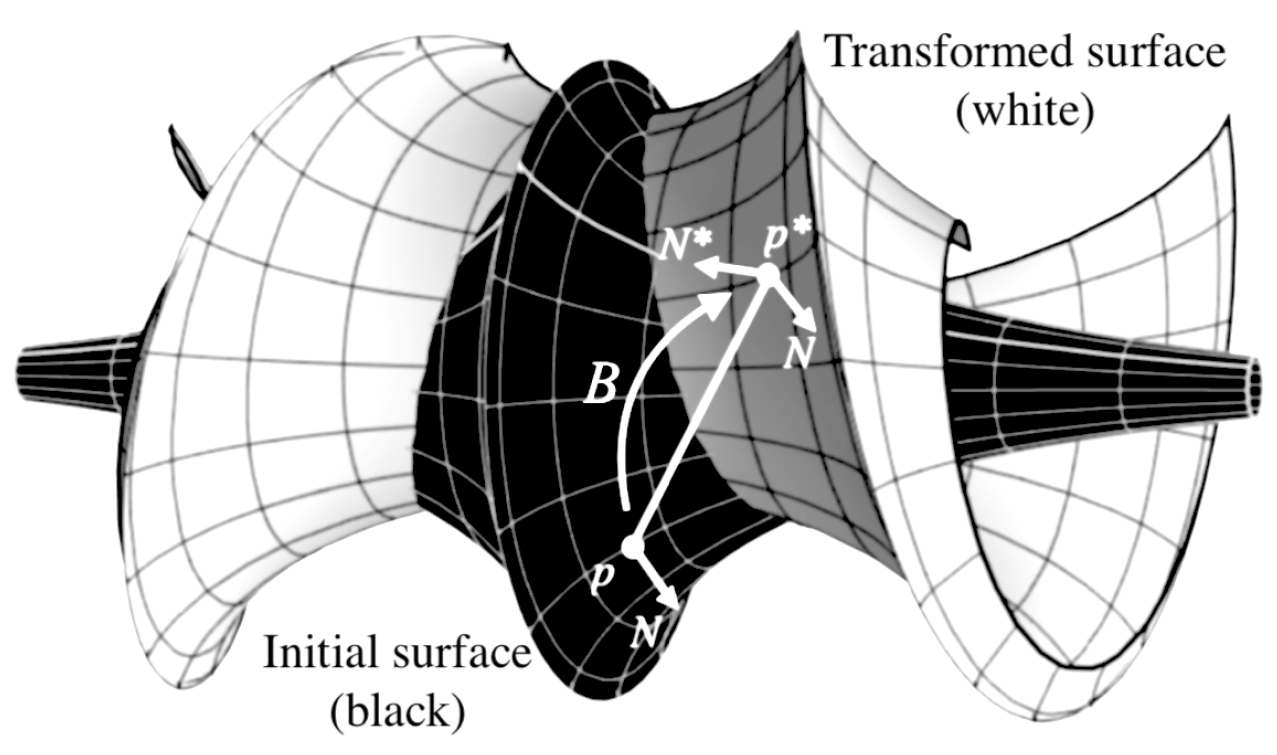

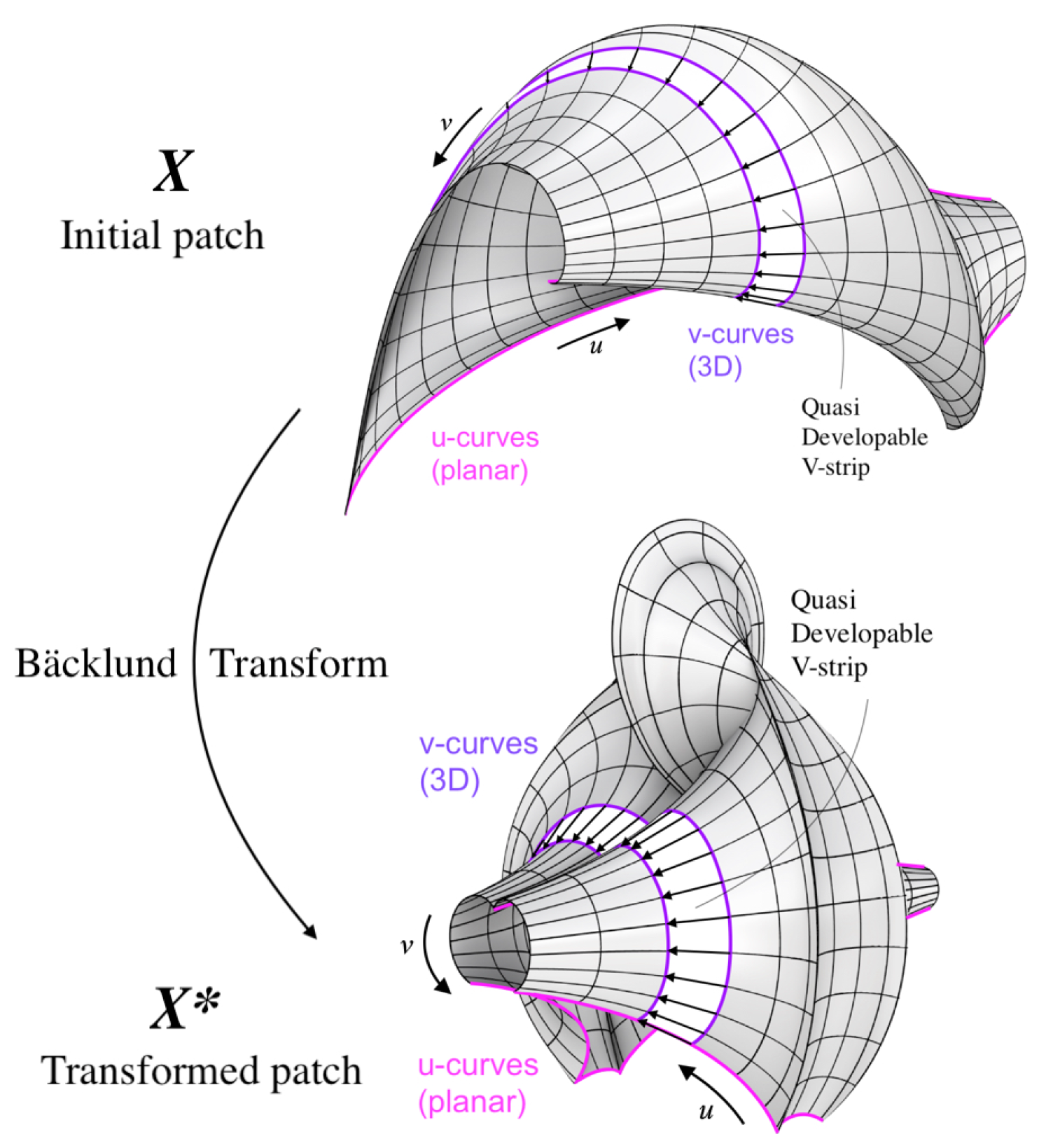

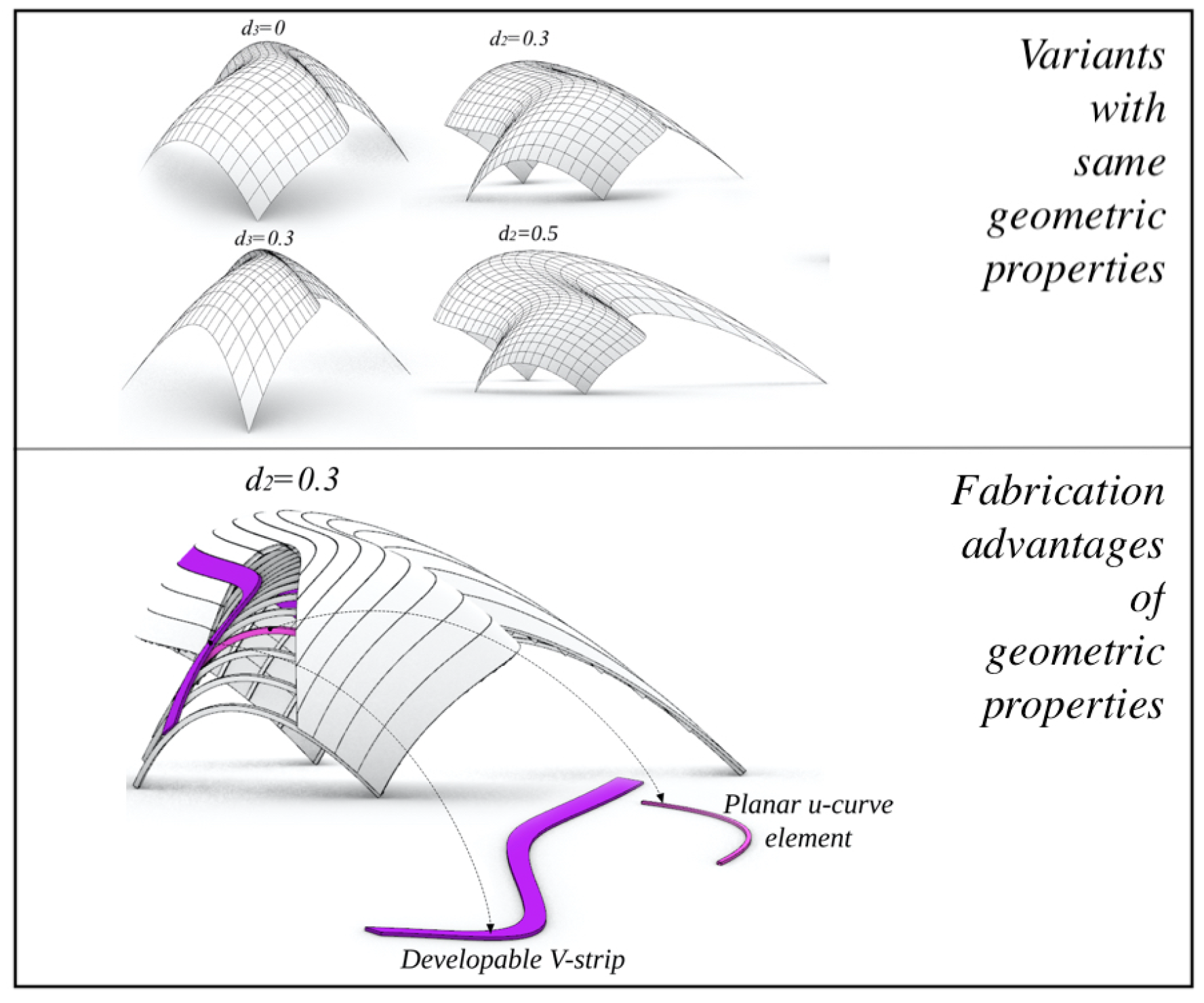

• Level 3 - Bäcklund transform: This is a bijective mapping

B between two surfaces of the same nCGC

for some

. Such that each line joining corresponding points

is tangent to both surfaces, and has constant length

, while the normals

to both surfaces have a constant angle

, as seen in Figure (

Figure 12).

More analytically, a Bäcklund transform

of

X (a principal nCGC Tchebyshef patch of angle

) is:

Starting with a degenerate patch

(with

), applying Bäcklund transform with generic inclination

yields the Dini-type, while applying it with

yields PS-type and upon second application with

yields Kuen-type (for more details cf. [

18]).

2.4. Extra Possibilities

We can also mix levels of transforms and properties to increase the design options by extra possibilities.

• Extra possibilities - Projective transform: Applying a projective transform to a principal CU-patch, yields a conjugate PU-patch. If in addition the initial patch has developable V-strips and is: Revolution-type (

4), Cyclide-type (

5), Joachimsthal-type (

7) (with

), Pencil-type (

8) (with

), its projective transform also has developable V-strips.

• Extra possibilities - Möbius transform: Applying a Möbius transform to a principal nCGC Tchebyshef PU-patch, yields a principal patch with spherical

u-curves. In fact, a Möbius transform of a conjugate CU-patch is just a CU-patch, while a Möbius transform of a principal PU-patch of Monge-type (

6) or Pencil-type (

8), is just a principal patch.

• Extra possibilities - Bäcklund transform: Observe that using the parameter

w appearing in the expressions of the Kuen-type, as a coordinate, yields a 3-dimensional patch

, parameterizing a triply orthogonal system of surfaces (TOS) called Ribaucour TOS (R-TOS). Note that, patches

are principal nCGC Tchebyshef PU-patches, while the patches

and

are principal with

w-curves circular, for any fixed

. Up to renaming parameters, the principal patches

will be considered CU-patches with developable V-strips (which we will call R-TOS-Type). The same goes for their Möbius transforms, as seen in Figure (

Figure 14).