1. Preliminaries

Quantum field theory (QFT) was developed long ago to describe elementary particles, such as the electrons and neutrons, their interaction with each other and with their environment. However, the theory had to be augmented by ad hoc rules for computing physical processes because all such computations are plagued with infinities. Up to date, all efforts to develop a practical QFT without these ad hoc rules (called renormalization) were not fully satisfactory. In this work, we attempt at a resolution of this shortcoming by introducing an algebraic version of QFT based on orthogonal polynomials and special functions that does not require renormalization. That, is a theory in which closed-loop integrals in the Feynman diagrams for calculating transition amplitudes are finite. We assume basic knowledge of QFT and thus will not dwell on a review of the theory. Interested readers may consult any of the classic textbooks on the subject such as those in Refs. [

1,

2,

3]. Additionally, we will not assume advanced knowledge in the theory of special functions and orthogonal polynomials. It is sufficient that the reader be familiar with the properties of well-known polynomials such as the Hermite, Laguerre, Chebyshev, Gegenbauer, ...etc. At least, one must know where to find such properties by looking at any of the numerous books on orthogonal polynomials like those listed in [

4,

5,

6,

7]. For the purpose of the present development, one should be aware that an orthogonal set of polynomials has an associated weight function, satisfies a three-term recursion relation and an orthogonality.

We start by showing that the conventional representation of the free quantum field in the linear momentum space could be rewritten in an equivalent form in the energy space with an algebraic structure built on orthogonal polynomials. For example, the differential wave equation in conventional QFT becomes an algebraic three-term recursion relation satisfied by the orthogonal polynomials associated with the given quantum field. Therefore, instead of solving a differential wave equation, one can simply solve an algebraic equation. We should note, however, that the algebraic structure of this theory is fundamentally and technically different from that which is commonly known in the mathematics/physics literature as Algebraic Quantum Field Theory (AQFT). A survey of AQFT can be found in [

8] and references cited therein. Next, we show that the equal-time commutation relation of the quantum field and its canonical conjugate in this equivalent algebraic theory is a direct consequence of the orthogonality of the associated polynomials and the completeness of a corresponding set of spatial functions. Additionally, we show how the basic singular two-point function, whose time ordering leads to the Feynman propagator, is constructed in a simple and transparent form using these orthogonality and completeness. Nonetheless, a free QFT (i.e., a theory without interaction) does not carry much physical significance beyond the obvious requirement of being physically and mathematically consistent and preferably elegant. Hence, we come to our most important findings where we show that closed loop integrals in the Feynman diagrams used for calculating transition amplitudes in interacting models in this algebraic theory are finite. We verify this claim in a typical model for few sample diagrams. This property relies predominantly on the orthogonality property of the associated polynomials. We give a numerical illustration showing that the finiteness property of this model continues to higher order loops. It remains to be seen whether this remarkable property is maintained in other physically relevant interaction models.

To make the presentation clear and simple, we work in 1+1 Minkowski space-time and adopt the conventional relativistic units

. We do acknowledge that spinors and vector fields in such space-time may not carry much of a physical significance. However, the mathematical formulation introduced here could easily be extended to higher dimensions. Readers interested in the 3+1 space-time version of the formulation can refer to Ref. [

9] for details.

2. Algebraic Structure in Conventional QFT

In conventional QFT, the positive energy component of the free quantum field

associated with a scalar particle in 1+1 space-time is written as the following continuous Fourier expansion in the linear momentum

k-space [

1,

2,

3]

where the creation/annihilation field operators satisfy the commutation algebra

The free Kelin-Gordon wave equation

gives the energy-momentum relation for a free particle as

.

Now, it is well-known that the oscillatory function

(plane wave) in Eq. (1) has the following point-wise convergent expansion

where

is the Hermite polynomial of degree

n in

y, and

λ is an arbitrary scale parameter with the dimension of energy. Applying the differential operator

on this expression and using the differential equation of the Hermite polynomial,

, we get

where

. To compute the term

, we repeat the recursion relation of the Hermite polynomial,

, twice resulting in

Therefore, if we write

where

or

, then

becomes a linear combination of

and

with constant coefficients that depend on the index

n. That is,

results in a three-term recursion relation for

that can be made symmetric by adopting the following normalization

Consequently, we can write

for

and where

Therefore, if we write the series (2) as follows

then

with

or

, and Eq. (4) becomes

Making the replacement

and

in the second and third terms in the sum, respectively, we obtain

for

. We write

making

. Therefore, the free Klein-Gordon wave equation

becomes the following algebraic three-term recursion relation

where

and making

a polynomial in

z of degree

n. In fact, one can easily verify that

(where

or

)

1 solves the recursion (11). We call

the “spectral polynomials” and

z the “spectral parameter”. Using the orthogonality of the Hermite polynomials,

, we obtain the following orthogonality of the spectral polynomials

where

is the associated weight function that reads

, which is positive definite for

, and

. Therefore, given the algebraic structure defined by the spectral polynomials

and the associated complete spatial functions

, we can rewrite the quantum field (1) as

In

Appendix A, we give another representation equivalent to (13) but with a different set of spectral polynomials

(the Gegenbauer polynomials) and spatial functions

(the Bessel functions). Inspired by these expansions and the algebraic structure associated with the spectral polynomials, we consider in the next section the following quantum field representation, which is an

E-space equivalent to the

k-space representation (1) or (13), that reads

where

,

and

to be determined. Based on this (and other similar) mapping of the quantum fields from the

k-space to

E-space using such an expansion, we present in the following section a systematic formulation of our proposed algebraic QFT.

3. The Algebraic QFT

In this proposed theory, the positive energy component of the scalar quantum field in 1+1 Minkowski space-time is represented by the following continuous Fourier expansion in the energy

where

and

making

.

are

real and dimensionless set of functions of the spectral parameter

z whereas

is operator-valued (the annihilation operator) that satisfies the following commutation algebra

where the function

is positive definite to be determined below by canonical quantization. Consequently, unlike the conventional theory where the operator

creates/annihilates the entire quantum field, here

creates/annihilates a single spectral mode (the

nth mode) of the quantum field.

is a complete set of spatial functions in configuration space that satisfy the following differential relation

where

is a universal constant of inverse length dimension (a universal scale/mass). The coefficients

are real dimensionless parameters that are independent of the energy and such that

for all

n. Using (17), the free Klein-Gordon wave equation

becomes the algebraic relation (11) for

and with

. Equation (11) is a symmetric three-term recursion relation that makes

a sequence of polynomials in

z with the two initial values

and

a two-parameter linear function of

z. Now, Eq. (11) has two linearly independent polynomial solutions. We choose the solution with the initial values

and

. The spectral theorem (a.k.a. Favard theorem) [

4,

5,

6,

7] states that the polynomial solutions of the recursion (11), with the recursion coefficients

being positive definite, must satisfy the orthogonality relation (12) with

being the associated weight function, which is positive definite and will be related to

by canonical quantization. The fundamental algebraic relation (11), which is equivalent to the free Klein-Gordon wave equation, is the reason behind the algebraic setup of the theory and for which we qualify this QFT as algebraic. In fact, postulating the three-term recursion relation (11) eliminates the need for specifying a free field wave equation. Furthermore, once the set of spectral polynomials

is given then all physical properties of the corresponding particle are determined.

Now, the conjugate quantum field

is obtained from (15) by complex conjugation and the replacement

where the pair

satisfy the following orthogonality and completeness relations

Therefore, we write

as

Using the commutators of the creation/annihilation operators shown above as Eq. (16) and noting that

, we can write

The orthogonality (12) and the completeness (18b) turn this equation with

into

provided that we take

, which makes the commutation (16) read as follows

Moreover, it is straightforward to write

In the canonical quantization of fields [

1,

2,

3], equations (21) and (23) give the canonical conjugate to

as

. Moreover, in analogy with conventional QFT [

1,

2,

3], we can write Eq. (20) as

giving the singular two-point function

as follows

Moreover, Eq. (21) and Eq. (25) give: . The vacuum expectation of the time ordered gives the Feynman propagator . Therefore, the elements needed to define the free sector of this algebraic theory are: the spectral polynomials and the spatial set of functions together with their conjugates .

It is interesting to note that if we identify the scalar quantum field given by the conventional representation (1) with the new algebraic representation (15), then using the expansion (2) we obtain: , as given by Eq. (5), and . Hence, we obtain the annihilation operator map between the two representations where and we have used the on-shell relation for free fields.

A real (neutral) scalar particle in 1+1 space-time is represented by the quantum field with . On the other hand, a complex (charged) scalar particle is represented by a quantum field whose positive-energy component is and its negative-energy component is where is identical to (15) but with the associated spectral polynomials along with their recursion coefficients , weight functions , and with the annihilation operators that satisfy where r and stand for ±.

The particle propagator is an operator that takes the particle from the space-time point

to

with

. In other words, the particle is created from vacuum at

then annihilated later at

. In the algebraic formulation, the equivalent “spectral propagator” reads

where

is the vacuum. Now, since

, then we can write

We designate the spectral propagator by

that takes

[more precisely,

]. That is, the propagator must satisfy

The orthogonality (12) shows that the representation

satisfies (27). This is also suggested by the two-point function of equation (26) that could be rewritten as follows

Consequently, is the propagator for individual spectral modes of the quantum field () leaving other modes unaffected, which is unlike in the conventional theory where the entire quantum field is propagated. Moreover, using the completeness of the spectral polynomials that reads , one can also show that this propagator has the property . Furthermore, using the orthogonality (12), it is evident that . Additionally, it has the exchange symmetry . Energy conservation, on the other hand, which is evident by the presence of the Dirac delta function in the propagator equation (26), implies that . In the following Section, we show how this propagator enters in the calculation of the scattering amplitudes via the Feynman diagrams.

4. Interaction in the Algebraic QFT

In this Section, we show how to calculate the scattering amplitude

in a generic interaction model. We consider the interaction Lagrangian

and choose

to be a scalar,

a spinor

2, and

a dimensionless coupling tensor of rank three that couples individual spectral field modes. This interaction Lagrangian resembles that of QED where the scalar field is replaced by the massless vector field (the photon). If we designate

as the set of spectral polynomials associated with the spinor component

, then we can write the corresponding spinor annihilation operators

and their anti-commutation relation

where

and

is the spinor weight function. For simplicity, we consider neutral particles and a single spinor component where we can write

where

is the two-component spinor basis functions that satisfy equations (B5) and (B9) in

Appendix B of Ref. [

9]. The fermionic structure of the interaction dictates that the coupling tensor is antisymmetric in the fermionic indices. That is,

.

As illustrative example of calculating the scattering amplitudes, we start by considering the first order (one-loop) correction to the free propagator (i.e., self-energy).

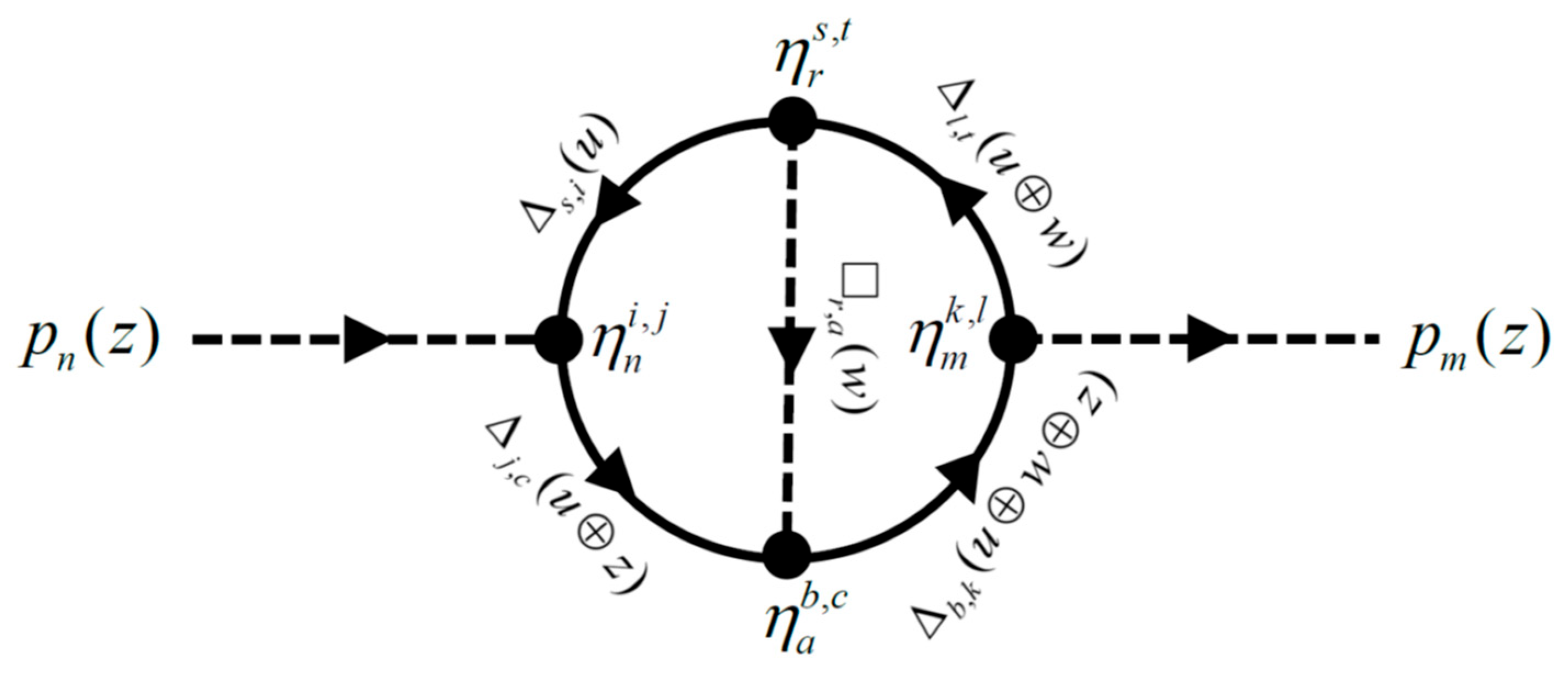

Figure 1 represents the associated Feynman diagram in this model where the propagator for the scalar (spinor) is represented by a dashed (solid) curve. In the following figures, we designate the spectral propagator for the spinor as

with

and for the scalar as

with

. Note that conservation of energy gives

.

Since the spectral polynomials carry a faithful representation of the quantum field, we adopt the notation

for the amplitude shown in the Figure with

. Moreover, the spinor propagator for the top part of the closed loop is

with

whereas for the bottom part it reads

with

and

(i.e., the signs of

E and

are the same) since

w should be positive. In the algebraic system introduced in Ref. [

10], the spectral parameter addition (30) is written as

. Therefore, to compute the amplitude

of

Figure 1, we integrate over all possible values of

u and sum over all possible indices (polynomial degrees)

. That is, to first order, we obtain the following spectral propagator for the scalar particle

The integral in this amplitude is one of the “fundamental SAQFT integrals” introduced in Ref. [

9] and denoted by

for

and

(i.e., for “monochrome propagation”)

3. In general, transition amplitudes like (31) are written as

where

is the term (or sum of terms) in the perturbation series that corresponds to a Feynman diagram (or rather topologically distinct Feynman diagrams) with

n vertices and

m loops.

4 Therefore, in (31)

and

whereas

is the second term in (31). The finiteness of the scattering amplitude is two-fold; one for integrals and another for sums. The first, is the finiteness of the integral, which is guaranteed by the orthogonality (12) of the spectral polynomials. In fact, we have shown in [

9] that the value of

falls within the interval [0,1] for all spectral polynomials satisfying the orthogonality (12). Moreover, its value goes to zero fast enough if any of the indices

i or

j go to infinity. The second issue in the finiteness of the scattering amplitude is the convergence of the series shown in Eq. (31), which depends on the asymptotics and sign signature of the components of the coupling tensor

.

In the integral of Eq. (31), the spectral parameter u assumes values that correspond to all possible ranges of the energy (i.e., and ). Therefore, the integral runs over all positive values of u from 0 to since . In the following section, we give a numerical illustration of the finiteness of the scattering amplitude (31) and show that monochrome propagation enhances the scattering amplitude. Additionally, we compute a truncated version of the series in (31) demonstrating converges as the number of terms increase.

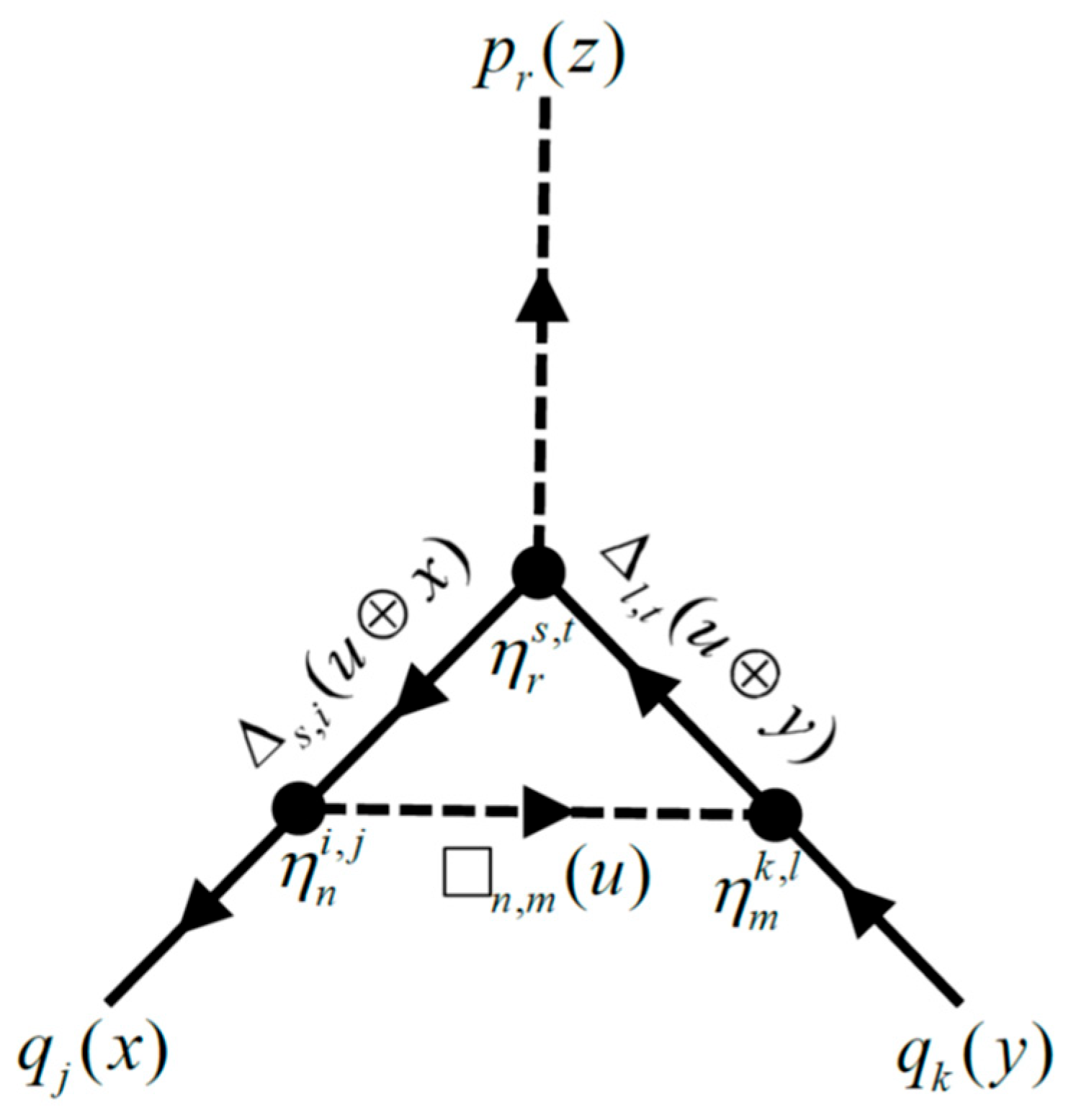

The second order (two-loop) correction to the scalar propagator contains several diagrams one of which is shown below as

Figure 2. To compute this second order correction, we integrate over all possible values of

u and

w and sum over all possible indices

and

. To simplify, we assume monochrome propagation where the degrees of the spectral polynomials are preserved in propagation. That is,

and

. In the diagram of

Figure 2, this is equivalent to the replacement

and

. Accordingly, we obtain the following second order contribution to the self-energy of the scalar propagator

Where

In the following section, we evaluate the double integral (32) for a given range of the scalar energy and a fixed set of the polynomial degrees and show that the value of the integral diminishes as the indices (or some of them) become large.

Finally, we consider the first order correction to the interaction vertex in this model. The associated Feynman diagrams are many (in fact, there are six topologically distinct diagrams). We consider here one of these diagrams, which is shown below as

Figure 3 where the spectral parameters are related by the energy conservation as

. The bare vertex

is just the coupling tensor element

independent of the energy. On the other hand, the value of the diagram in

Figure 3 reads as follows:

For monochrome propagation,

,

, and

, this expression simplifies to read:

In the following section, we show that the value of the integral in (35) falls within the range [0,1] and diminishes rapidly as the polynomial degrees increase.

5. Numerical Results

In this section, we evaluate the transition amplitudes presented in the previous section by the sample Feynman diagrams of

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. The results demonstrate finiteness of the closed-loop integrals for this model in our proposed algebraic QFT. For the purpose of calculation, we choose the model parameters as follows. We take a massless scalar (

) where the associated spectral polynomials

is the even Hermite polynomial

. The spectral polynomial

associated with the massive spinor is taken as the Laguerre polynomial

with

. Now, it is well-known that the odd/even Hermite polynomials could be expressed in terms of the Laguerre polynomials. That is, we can write

. Therefore, the orthonormal spectral polynomials, their normalized weight function and recursion coefficients associated with the scalar are as follows:

where

. On the other hand, for the spinor they read:

where

. In the calculation, we take

and

. Moreover, the elements of the coupling tensor are written in terms of the recursion coefficients (36b) and (37b) as follows

where

is a dimensionless coupling parameter. For a given set of indices

, we evaluate the integral in (31) that reads

with

. To evaluate the integral, we use Gauss quadrature integral approximation (see, for example, Ref. [

11]). In such calculation, we start by computing the eigenvalues and normalized eigenvectors of an

tridiagonal symmetric matrix

J whose diagonal elements are

and off-diagonal elements are

, where

M is the order of the quadrature such that

and

are those given by (37b). If we call such eigenvalues

and the corresponding normalized eigenvectors

, then the integral (39) is approximated as follows

where

is an

diagonal matrix whose elements are

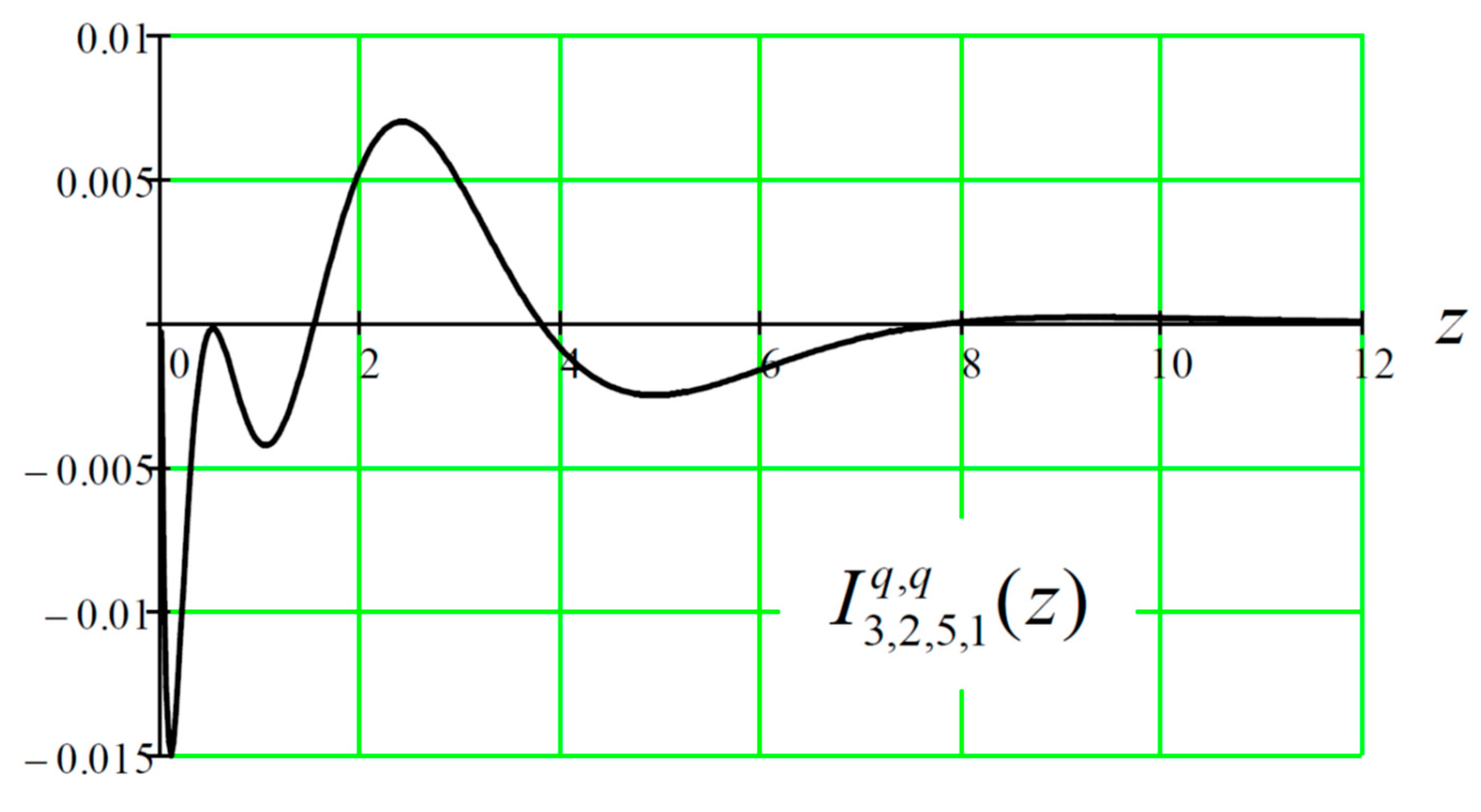

Figure 4 shows the result of such an evaluation for a given range of the scalar energy

.

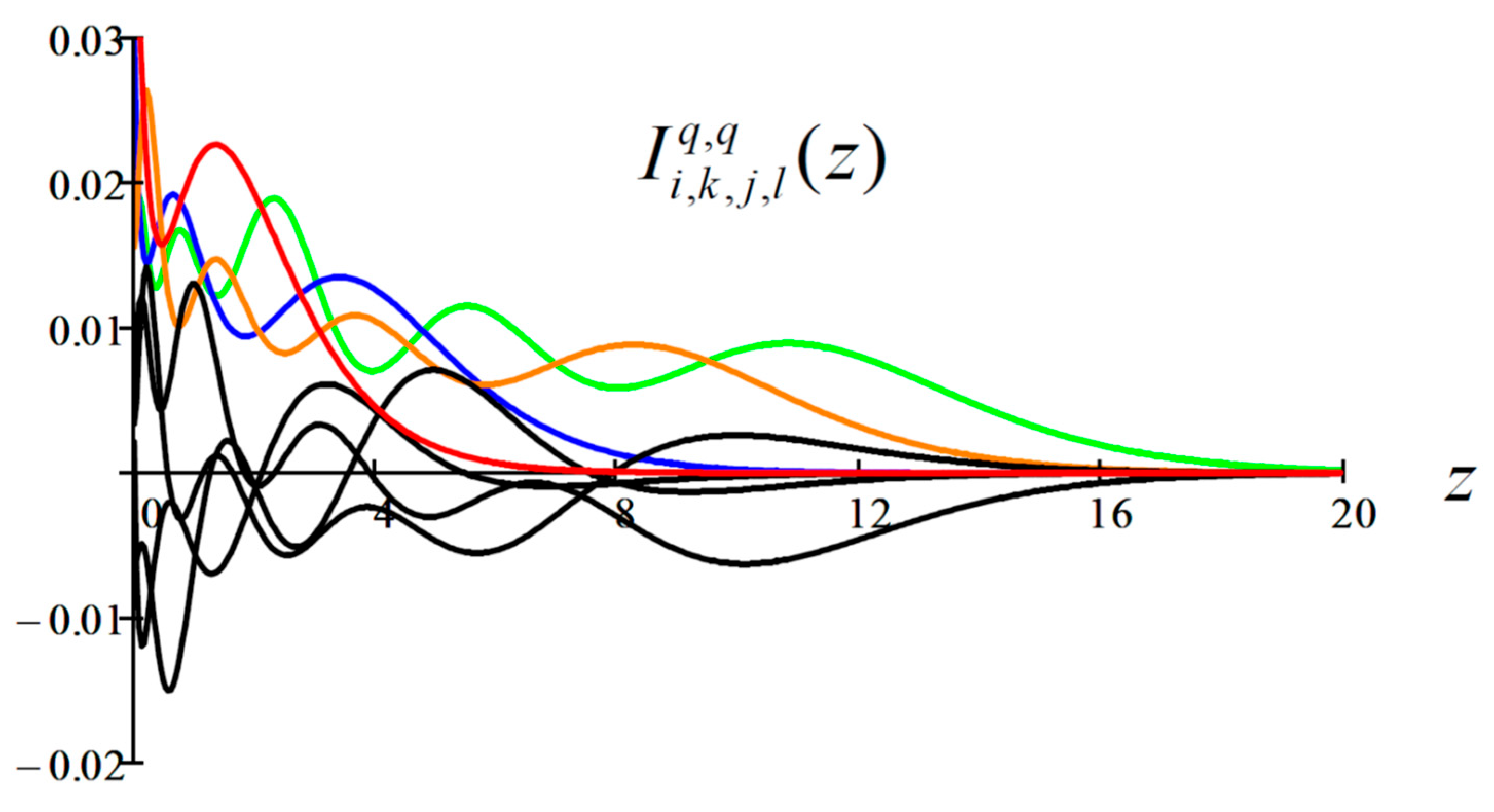

Figure 5 is a plot of

in colors corresponding to monochrome propagation superimposed by several polychrome propagation

in black. This figure shows that monochrome propagation is (as expected) positive definite boosting the value of the sum in (31) whereas polychrome propagation results in cancellations enhancing fast convergence of the sum. It is also evident from these figures that the magnitude of the integral (39) is less than one. In

Appendix B, we use a linearization technique [

12] to simplify the polynomial product in the integral (39).

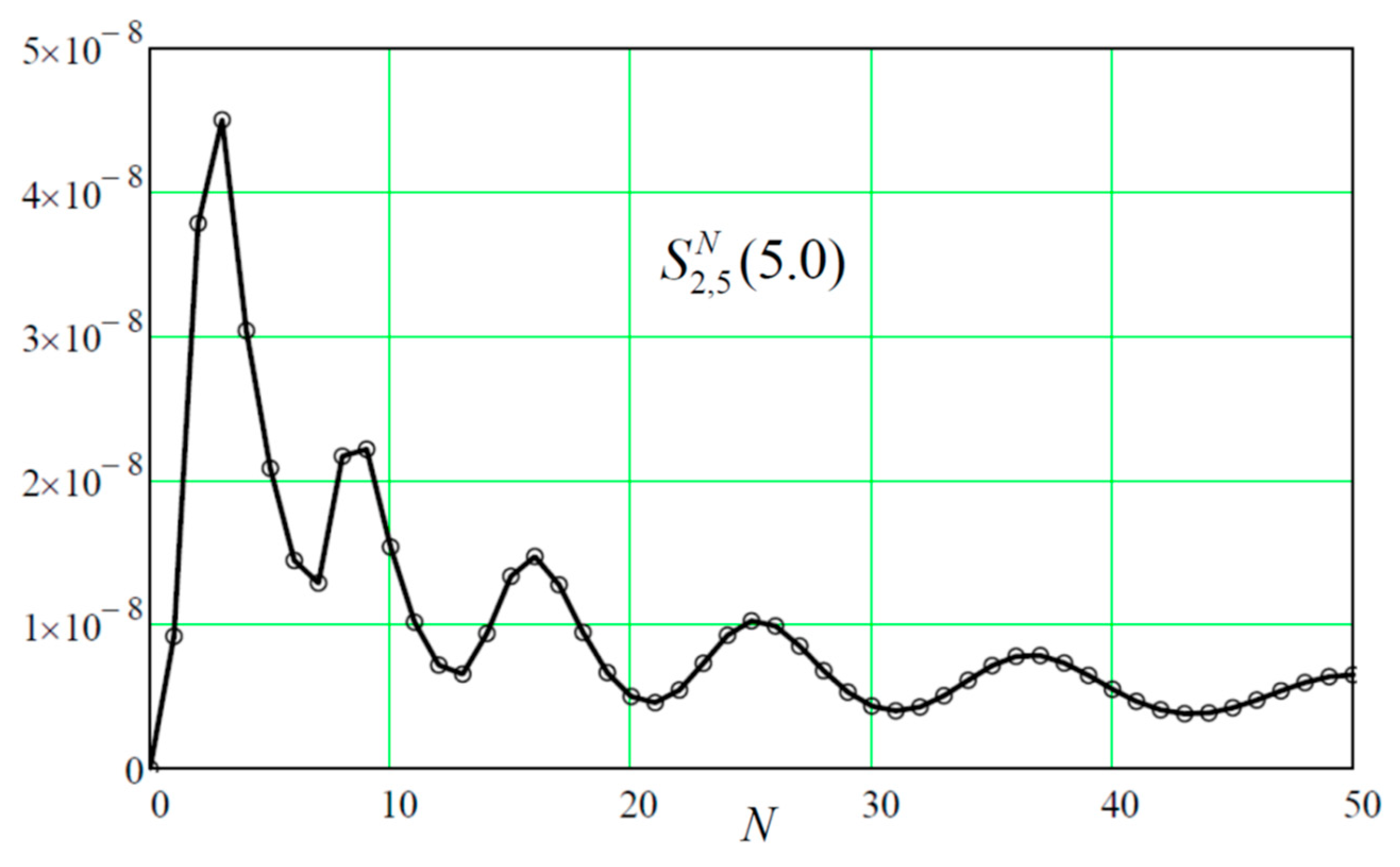

Moreover, to demonstrate convergence of the calculation of the transition amplitude (31), we evaluate the same self-energy diagram to first order for a fixed energy and polynomial degrees

n and

m but as a function of the number of terms

N in the sum

Figure 6 illustrates convergence of the series

as

N increases where we took

.

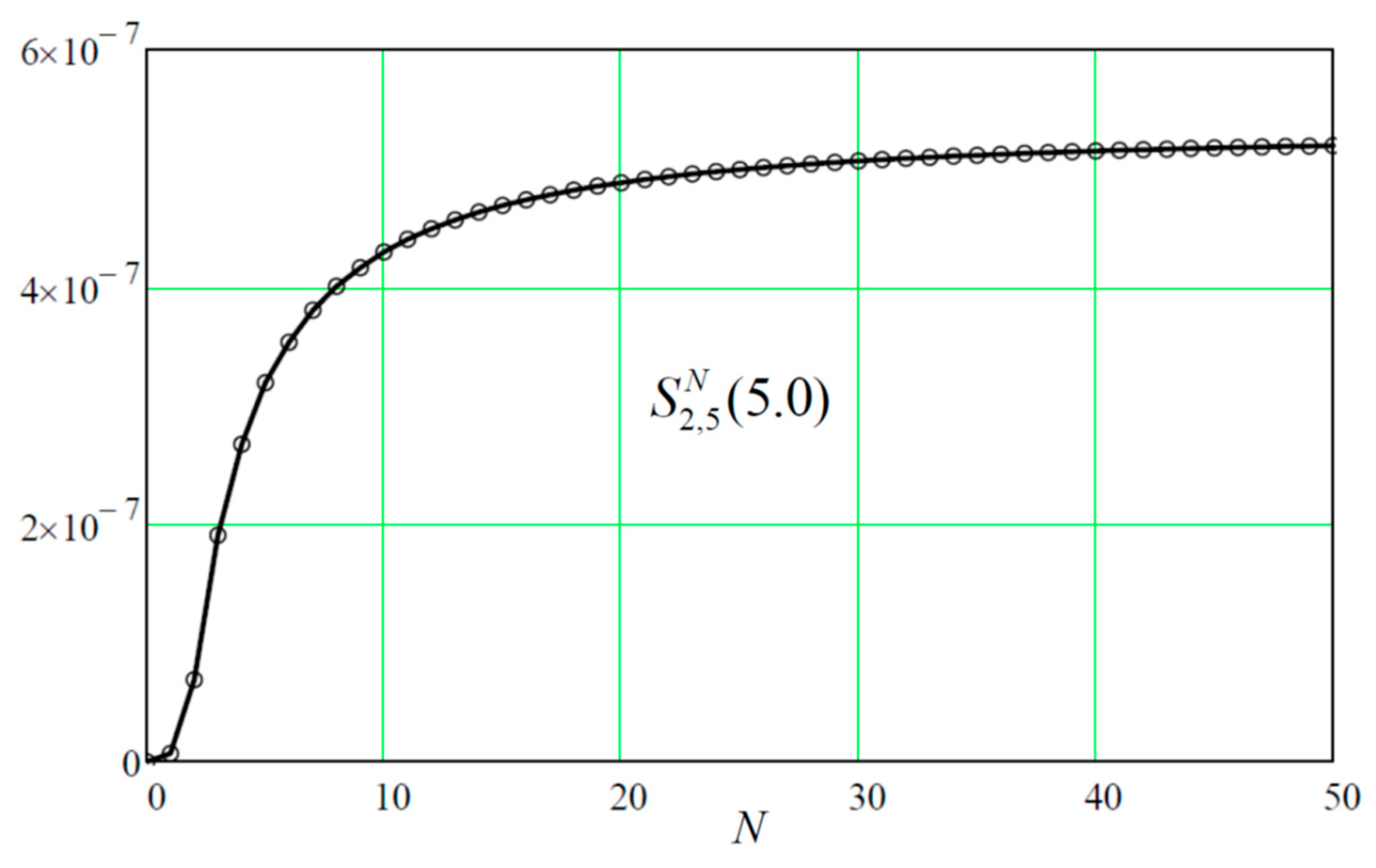

Figure 7 is a reproduction of

Figure 6 after imposing monochrome propagation where

. Therefore, the scalar propagator could be written to first order as follows:

where

could be interpreted as the square of the energy dependent coupling parameter of the model.

Table 1 is a list of

for monochrome propagation and for several values of the energy

and spinor parameter

.

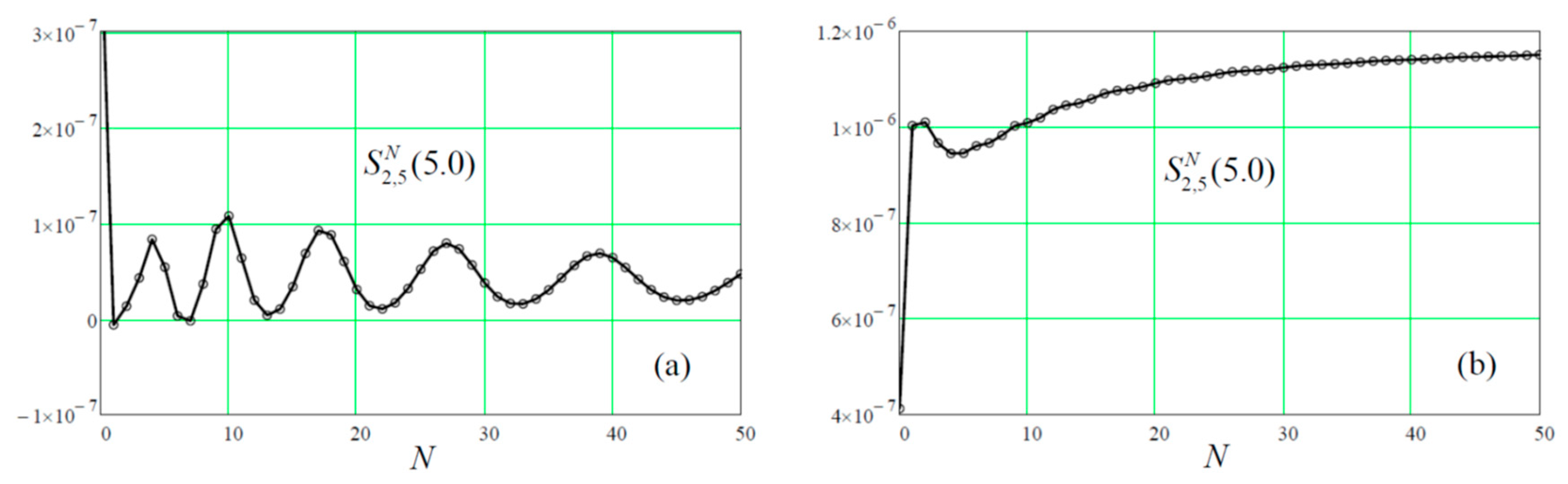

If we repeat the same self-energy calculation but for the spinor propagator, we obtain the following result to first order

Next, we evaluate the double integral associated with the diagram of

Figure 2 for mono-chrome propagation and given by Eq. (32) that reads

where

,

and

.

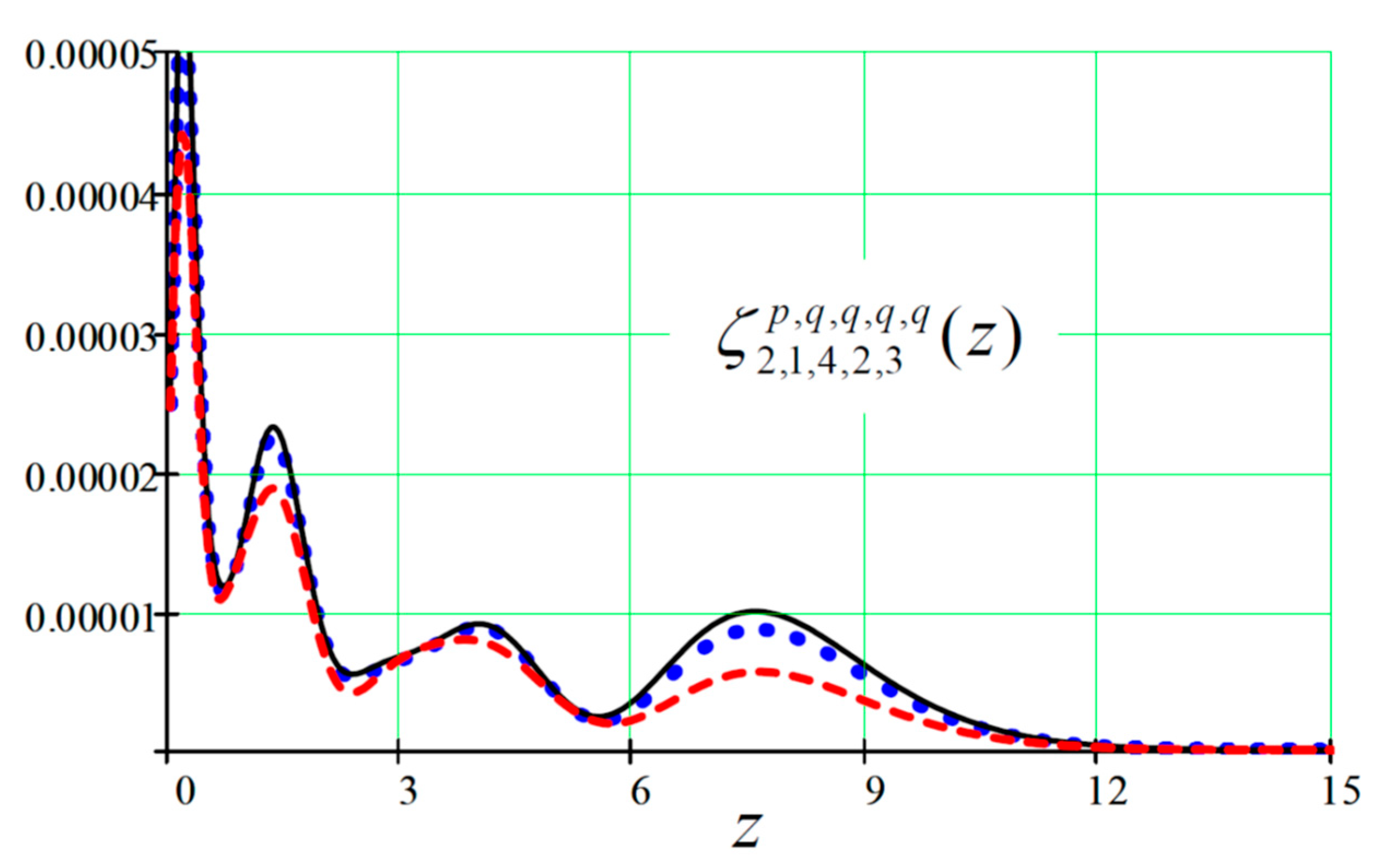

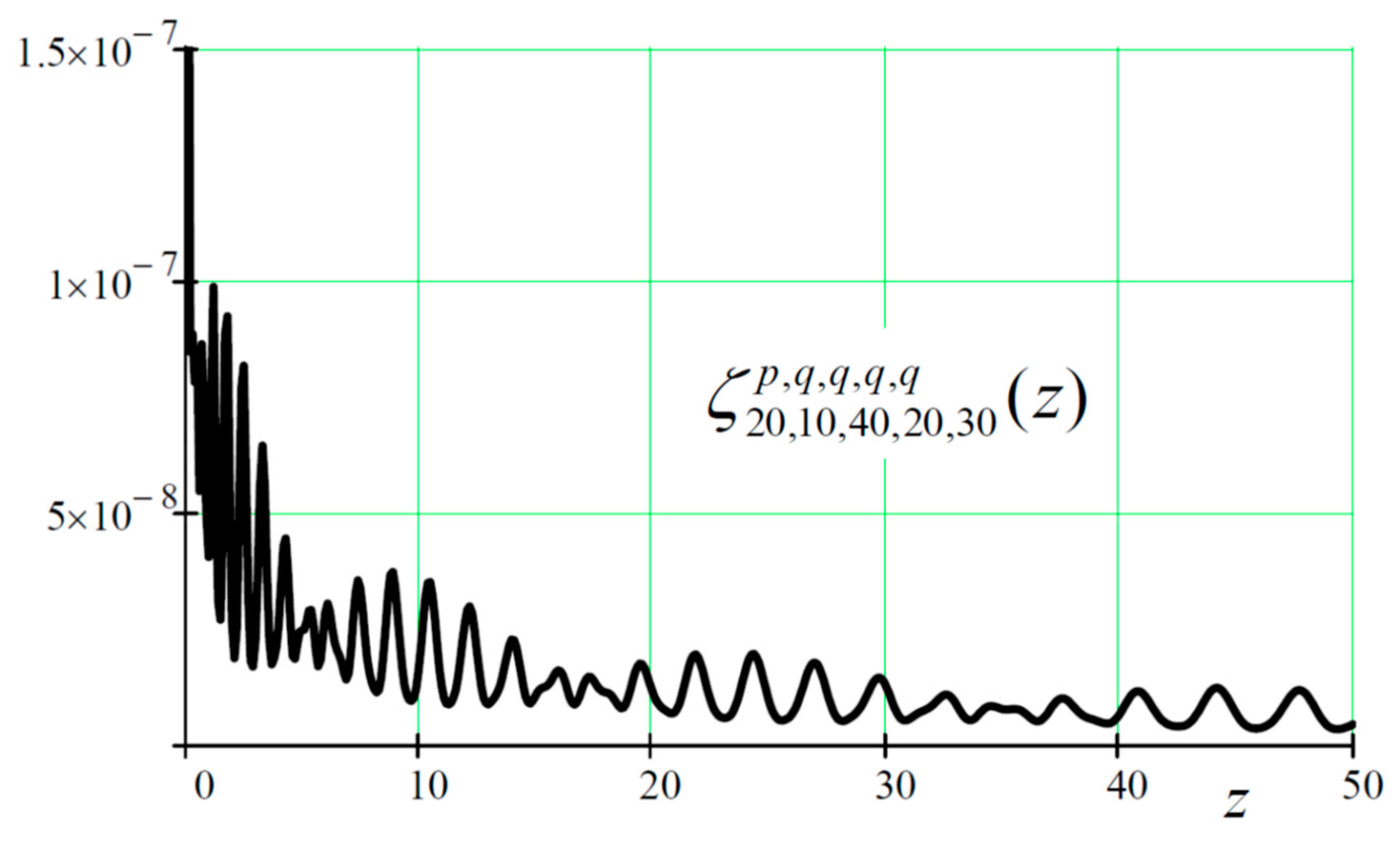

Figure 9 is a plot of

for a given set of indices and range of scalar energy. The figure is a superposition of three evaluations of the integral using an increasing order of Gauss quadrature: 20 (dashed red), 40 (dotted blue), and 60 (solid black).

Figure 10 is a reproduction of

Figure 9 (with a Gauss quadrature order of 60) but for large values of the indices (10 times those of

Figure 9). The figure demonstrates diminishing values for the integral (of the order of 200 times less). For this latter calculation, we used the large degree asymptotics of the Laguerre polynomials to write

where we have used

.

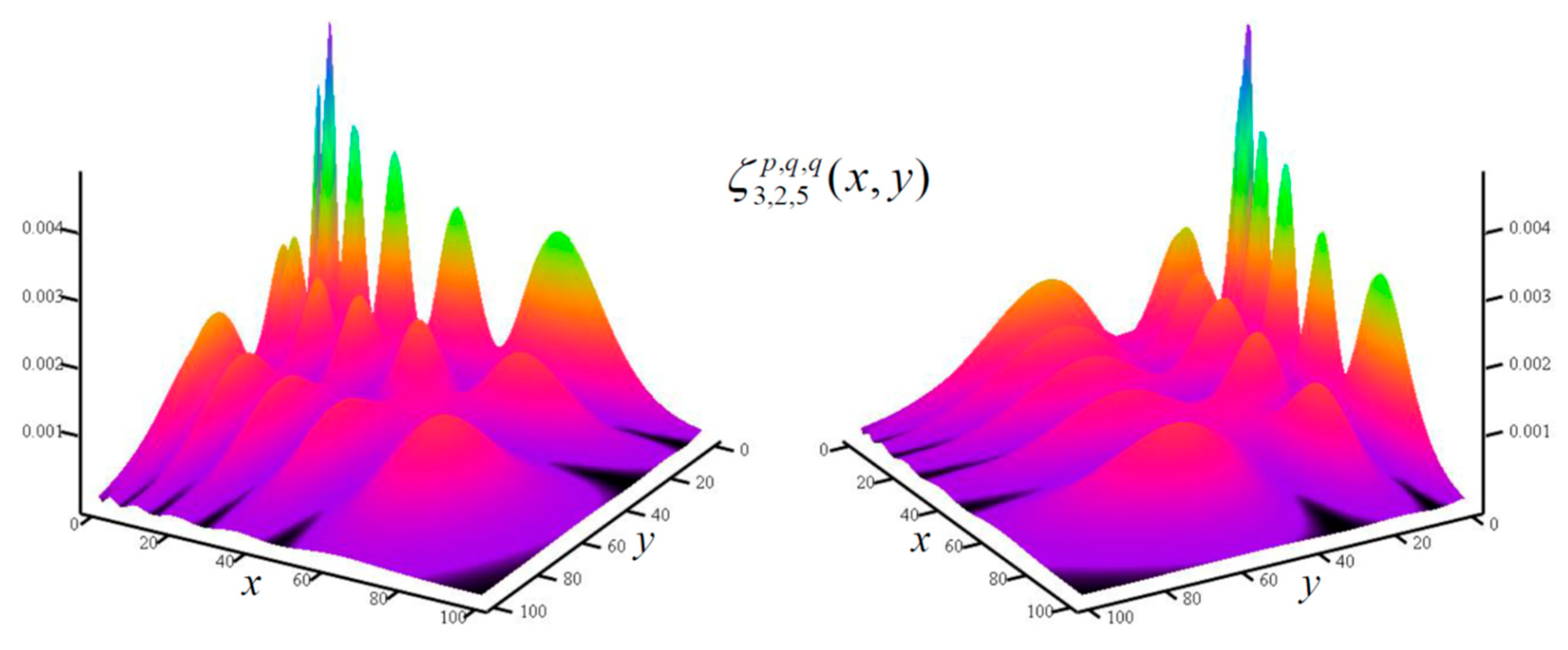

Finally, we evaluate the integral in the vertex diagram of

Figure 3 for monochrome propagation as given by Eq. (35) that reads

where

and

.

Figure 11 is a 2D plot of

for the indices

and spinor particle energy ranges

and

.

Figure 1.

Feynman diagram for the first order (single loop) correction to the scalar propagator (i.e., self-energy) in the model .

Figure 1.

Feynman diagram for the first order (single loop) correction to the scalar propagator (i.e., self-energy) in the model .

Figure 2.

One of the Feynman diagrams contributing to the second order (two-loop) correction to the scalar propagator (i.e., self-energy) in the model

Figure 2.

One of the Feynman diagrams contributing to the second order (two-loop) correction to the scalar propagator (i.e., self-energy) in the model

Figure 3.

One of the Feynman diagrams contributing to the first order (one-loop) correction to the interaction vertex in the model .

Figure 3.

One of the Feynman diagrams contributing to the first order (one-loop) correction to the interaction vertex in the model .

Figure 4.

Gauss quadrature approximation of the integral (39) with a quadrature order of 100.

Figure 4.

Gauss quadrature approximation of the integral (39) with a quadrature order of 100.

Figure 5.

Plot of the integral (39) corresponding to monochrome propagation as in red, in green, in blue, and in brown. Plots in black correspond to polychrome propagation for , , , and .

Figure 5.

Plot of the integral (39) corresponding to monochrome propagation as in red, in green, in blue, and in brown. Plots in black correspond to polychrome propagation for , , , and .

Figure 6.

The partial sum defined by Eq. (41) for , , , and . The elements of the coupling tensor in this model are given by Eq. (38).

Figure 6.

The partial sum defined by Eq. (41) for , , , and . The elements of the coupling tensor in this model are given by Eq. (38).

Figure 7.

Reproduction of

Figure 6 after imposing monochrome propagation.

Figure 7.

Reproduction of

Figure 6 after imposing monochrome propagation.

Figure 8.

Reproduction of

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 for the spinor particle: (a) polychrome propagation, (b) monochrome propagation.

Figure 8.

Reproduction of

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 for the spinor particle: (a) polychrome propagation, (b) monochrome propagation.

Figure 9.

Plot of the integral (44) demonstrating convergence by increasing the Gauss quadrature order from 20 (dashed red), to 40 (dotted blue), to 60 (solid black).

Figure 9.

Plot of the integral (44) demonstrating convergence by increasing the Gauss quadrature order from 20 (dashed red), to 40 (dotted blue), to 60 (solid black).

Figure 10.

Reproduction of

Figure 9 (with a Gauss quadrature order of 60) but for 10 times the values of the indices demonstrating diminishing values (of the order of 200 times less) where we used the asymptotic formula (45) for the spectral polynomials.

Figure 10.

Reproduction of

Figure 9 (with a Gauss quadrature order of 60) but for 10 times the values of the indices demonstrating diminishing values (of the order of 200 times less) where we used the asymptotic formula (45) for the spectral polynomials.

Figure 11.

Two-dimensional plot of the integral (46) viewed from two different angles. The x-axis scale is 0.15 while the y-axis scale is 0.30.

Figure 11.

Two-dimensional plot of the integral (46) viewed from two different angles. The x-axis scale is 0.15 while the y-axis scale is 0.30.

Table 1.

A list of for monochrome propagation and for several values of the energy and spinor parameter . In the formula (42), we took in calculating .

Table 1.

A list of for monochrome propagation and for several values of the energy and spinor parameter . In the formula (42), we took in calculating .

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

21.742 |

24.385 |

4.150 |

0.750 |

1.042 |

|

4.508 |

7.765 |

1.716 |

0.379 |

0.618 |

|

3.034 |

5.281 |

1.148 |

0.251 |

0.422 |

|

2.240 |

4.048 |

0.894 |

0.197 |

0.335 |

|

1.739 |

3.257 |

0.738 |

0.165 |

0.287 |

|

1.397 |

2.695 |

0.626 |

0.144 |

0.256 |