Introduction

Academic environments, especially those in specialized fields like medicine and healthcare education, encounter distinct challenges in managing visitor interactions, providing institutional information, and addressing administrative inquiries. These challenges are exacerbated by budget limitations, diverse multilingual learner and visitor populations, and the necessity of maintaining a professional yet welcoming atmosphere. Additionally, many medical and healthcare education institutions have advanced simulation equipment, including high-fidelity mannequins, that has completed its lifetime.

Recent advancements in AI-enabled reception systems have demonstrated their effectiveness across various sectors, including healthcare, hospitality, and corporate environments (Bazzano & Lamberti, 2018). These systems provide significant advantages in consistent service delivery, 24/7 availability, and multilingual support. However, purpose-built robotic receptionists often entail substantial investments that may be hard to justify in academic settings budgets.

Background and Context

The Institute of Learning includes four departments—Health Professions Education, Healthcare Simulation, Organizational Learning, and the Research Center—creating a complex reception environment with specific information needs and visitor types for each department. Learners, faculty, researchers, and external partners seek information that covers educational programs, simulation resources, organizational development initiatives, and research activities. International learners and visitors require multilingual support, particularly in specialized fields where technical terminology makes communication difficult. Furthermore, the Institute must handle variable traffic patterns related to academic calendars, with activity peaks occurring during registration, workshops, and special events.

The various departments of the Institute encounter specialized challenges concerning clinical placements, access to simulation laboratories, scheduling organizational training, and coordinating with research partners. These unique needs require a reception system that can integrate with diverse information systems while offering personalized assistance to learners, faculty, visitors, and researchers collaborators.

Research Aim and Questions

This research explores the feasibility, implementation, and initial effectiveness of repurposing medical simulation mannequins as AI-enabled receptionist systems for the Institute of Learning. It will focus on addressing the unique needs of its four specialized areas departments.

Specifically, this pilot study addresses the following research questions:

How can existing medical simulation mannequins effectively be used as AI-enabled receptionist systems for the Institute of Learning’s four departments?

What hardware and software architecture best supports AI receptionist functions on resource-constrained computing platforms typical in academic environments?

What adaptations are needed to meet the unique reception requirements of the Institute’s departments, especially concerning multilingual support and department-specific knowledge management?

How does a repurposed AI receptionist based on a mannequin perform during initial pilot testing compared to traditional receptionists’ approaches?

Methods

System Design and Implementation

Design Considerations

The Badr project was conceived to address specific challenges by repurposing an existing medical simulation mannequin as an AI-enabled robot receptionist for the Institute of Learning. The design process prioritized several key requirements: handling diverse inquiries spanning the Institute’s four departments—Health Professions Education, Healthcare Simulation, Organizational Learning, and the Research Center; providing multilingual support for international learners and visitors; integrating with departmental information systems; adapting to academic calendar-driven traffic patterns; and maintaining institutional branding and professionalism.

The system was designed to handle common reception scenarios specific to each department. For Health Professions Education, this included program information, faculty contacts, and course schedules. The Healthcare Simulation department required information on accessing simulation laboratories, reserving equipment, and training schedules. The Organizational Learning department needs to include workshop registration, consulting services, and resources for organizational development. The Research Center needed visitor management for research collaborators, information on ongoing projects, and grant details opportunities.

Physical Implementation

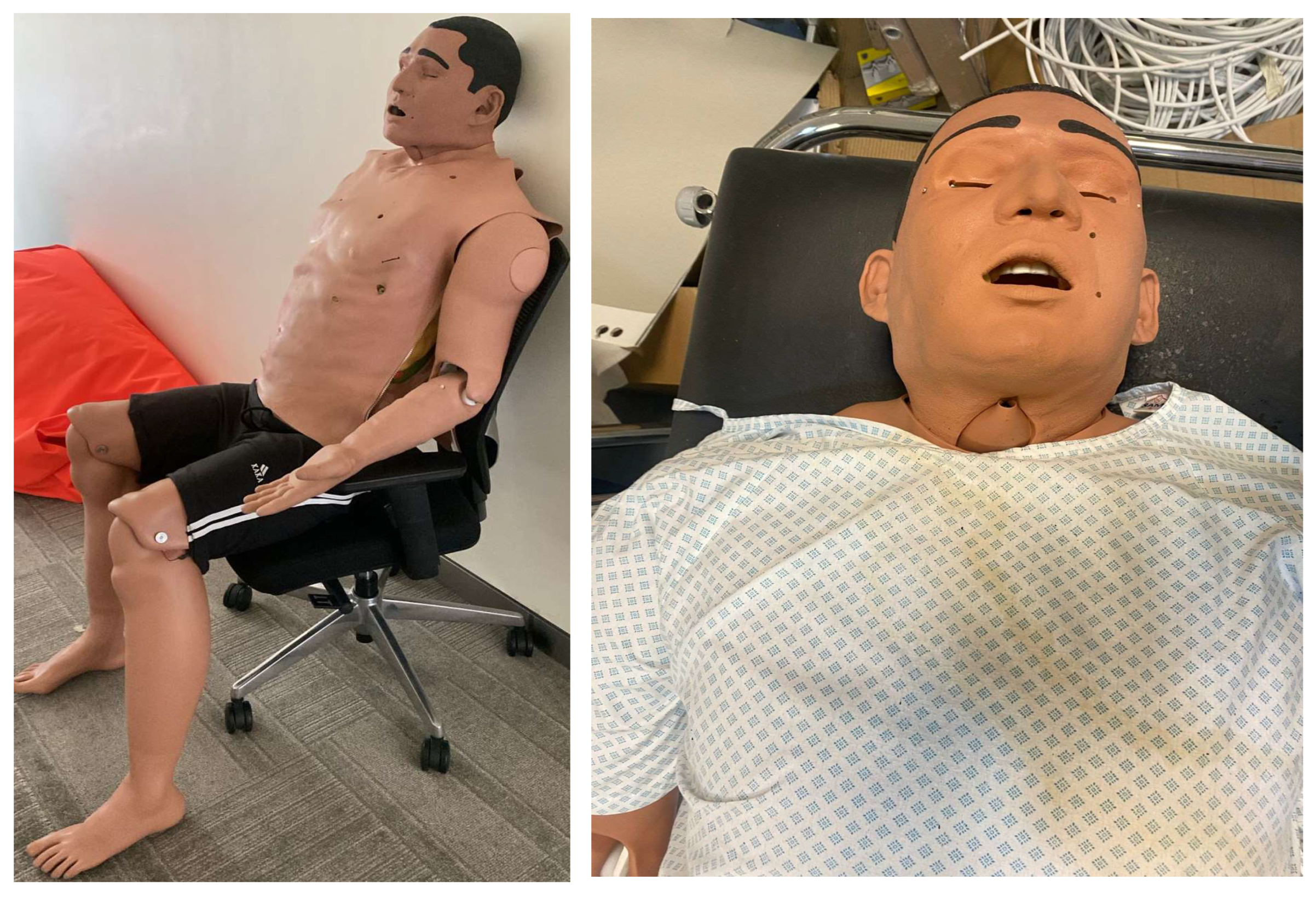

The project utilized an existing high-fidelity adult medical simulation mannequin, retrofitted to support the necessary hardware components for reception functionality at the Institute of Learning. Physical adaptations included internal structural changes to accommodate computing and audio components, integration of camera systems for facial recognition and visitor tracking, installation of motion-sensing capabilities for energy-efficient operation, embedding of audio input/output systems for natural conversation, and preservation of anthropomorphic features crucial for a human-like appearance interaction.

Figure 1 shows the original medical simulation mannequin before modification. This high-fidelity adult mannequin, initially designed for clinical training, provided an ideal anthropomorphic platform for repurposing due to its realistic proportions and structural integrity.

The mannequin’s positioning was carefully planned to comply with the Institute’s reception protocols. It was set semi-seated at the main reception desk, maintaining an eye level suitable for standing visitors and wheelchairs. Institutional branding elements were integrated through suitable attire and backdrop design, ensuring consistency with the Institute’s visual identity.

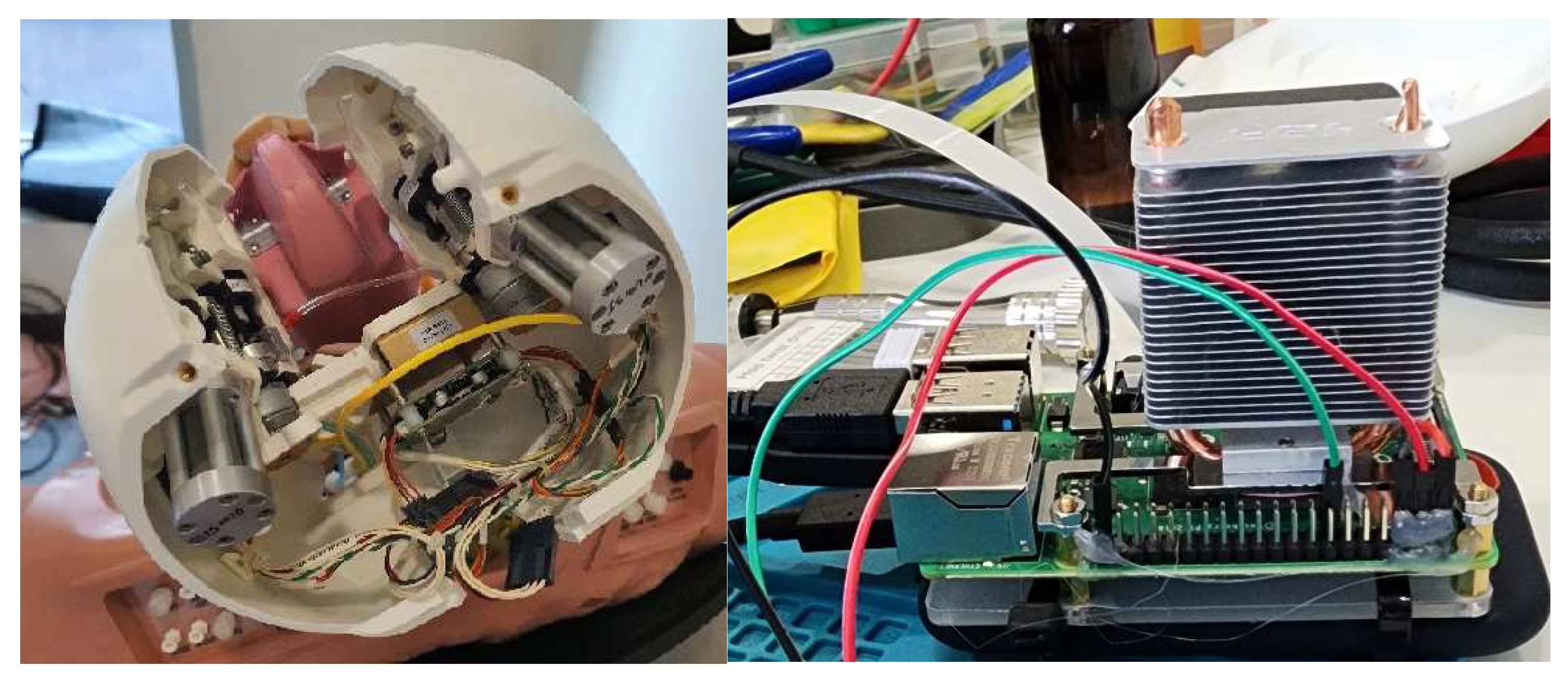

Following an iterative development process that tackled various hardware challenges, the final implementation featured a dual Raspberry Pi configuration. The primary computing system utilized a Raspberry Pi 4 Model B (Controller) for hardware interfaces, motion detection, and system orchestration. In contrast, the secondary system employed a Raspberry Pi 5 with HAT+ AI accelerator (Processor) for AI-intensive tasks. A Neore Model 3 Camera offered visual input with autofocus capabilities, while the audio system relied on a USB soundboard (4-pin speaker & mic combination). A PIR Motion Sensor connected via GPIO facilitated energy-efficient activation, and a SanDisk Extreme Pro X3 1TB SSD ensured reliable, high-performance storage. A radiator cooling system was implemented to prevent performance issues degradation.

Software Architecture

The software architecture employs a modular design pattern tailored to the Institute’s reception requirements, with components arranged into four primary layers. The Core System Layer includes a State Machine that manages conversation flow and system states, an Event Handler that coordinates responses to environmental triggers and user interactions, and a Resource Manager that optimizes resource allocation across the distributed system. This layer was created to accommodate the diverse interaction patterns typical of the Institute’s reception environment, ranging from brief directional inquiries to complex department-specific requests.

The Hardware Interface Layer includes a Camera Controller that manages image capture and preprocessing, an Audio Interface that handles speech input/output with noise filtering and adaptive gain control, and a Motion Detection module that processes PIR sensor data to trigger system activation. These components were optimized for the Institute’s reception context, focusing specifically on managing background noise during peak transition periods and adjusting to variable lighting conditions throughout the day.

The AI Component Layer features Face Recognition, which identifies returning visitors using a Multi-Sample Approach for improved accuracy; Natural Language Processing, which processes speech input and generates appropriate responses; and Speech Processing, which converts text to speech with enhanced naturalistic qualities. The natural language processing components were tailored to recognize terminology relevant to the Institute’s four departments, including educational terms, simulation equipment, organizational development concepts, and research methodologies.

The Institute Integration Layer includes systems for Email Notification, which alerts faculty and staff when visitors arrive; Calendar Integration, which verifies and manages appointment information across departmental scheduling systems; and a Departmental Systems Interface, which connects with information systems for the four departments, allowing access to relevant resources, events, and contact information. This layer enables Badr to provide accurate, up-to-date information specific to each department while maintaining appropriate privacy and security protocols.

Distributed Processing Implementation

A key innovation in Badr’s architecture is its distributed processing approach, which addresses the computational intensity of modern AI components while ensuring cost-effectiveness appropriate for academic budgets. The system allocates tasks based on processing requirements and real-time constraints, with the Raspberry Pi 4 (Controller) managing hardware interfaces, motion detection, basic state management, and system orchestration, while the Raspberry Pi 5 with AI accelerator (Processor) handles computationally intensive tasks including face recognition and NLP analytics.

This distribution enables real-time responsiveness for critical interaction functions while supporting advanced AI capabilities that would be impractical on a single embedded computing platform. The implementation includes inter-process communication mechanisms with optimized latency, failover capabilities to maintain basic functionality if the processor unit encounters issues, dynamic resource allocation based on current interaction needs, and synchronized state management across both computing systems units.

Institute-Specific Features

Multilingual Capabilities

A distinctive feature of Badr is its support for both English and Arabic, including the Emirati dialect. This capability addresses the specific needs of the Institute’s diverse learner and visitor population. The speech processing system employs Whisper-based speech recognition optimized for multilingual performance, incorporates context-aware language detection to switch processing pipelines automatically, provides dialect-specific adaptation for enhanced recognition of Emirati Arabic, and utilizes noise filtering and adaptive gain control to improve recognition in variable acoustic environments. Additionally, it delivers natural-sounding text-to-speech synthesis for both English and Arabic responses.

These multilingual capabilities are especially valuable in the Institute’s context, where international learners may encounter language barriers when accessing departmental services. The system includes specialized vocabulary relevant to each department in both languages, ensuring precise understanding and communication of technical terms, program information, and institutional resources procedures.

Visitor Management System

Badr implements a comprehensive visitor management system tailored to the Institute’s needs. The system differentiates among various visitor categories, including learners, faculty, researchers, external partners, and general visitors, further classifying them based on their intended department. This categorization allows for customized interaction flows according to visitor type and department destination.

Badr provides prospective learners information about educational programs in the institute’s departments. Current students receive assistance with course information, access to simulation laboratories, and research opportunities. Faculty and staff visitors are promptly notified to their hosts via email. Research collaborators are guided to the appropriate contacts within the Research Center. This organized approach facilitates efficient management of the various visitor types that characterize the Institute’s multidisciplinary environment.

Faculty Notification System

The faculty and staff notification system was designed to accommodate the dynamic schedules typical of the Institute’s academic environment. When a visitor arrives for a faculty or staff member in any of the four departments, Badr verifies the appointment against the faculty member’s calendar, sends a notification through the preferred channel (email or text message), provides status updates to the visitor regarding their host’s availability, and offers alternative contact options if the faculty member is unavailable.

The system offers customizable notification preferences for faculty members across all departments. This lets them specify their preferred notification methods and protocols based on their teaching, research, and administrative schedules. This flexibility is especially crucial in the Institute’s environment, where faculty commitments extend across multiple departments and activities.

Energy Efficiency System

Badr has implemented an energy-efficient activation system centered around the PIR motion sensor to align with institutional sustainability goals. This approach significantly reduces power consumption and computational load when the system is not actively engaged with visitors, supporting the Institute’s sustainability initiatives while maintaining responsive interaction capabilities.

The activation framework employs a tiered approach with four distinct modes: Standby Mode, which has minimal systems active while monitoring motion sensor input; Awareness Mode, where basic visual systems are activated upon motion detection to assess if interaction is necessary; Engagement Mode, which engages full AI capabilities upon direct interaction detection; and Processing Mode, which maintains interactions with optimized resources allocation.

This energy-efficient design supports the Institute’s sustainability objectives while ensuring that the system remains responsive during operating hours, even during the variable traffic typical in a multidepartmental academic setting environment.

Evaluation Methods

For this pilot phase, the Badr system was initially assessed through preliminary technical performance evaluations and limited user testing within the Institute of Learning environment. The evaluation metrics included evaluating the functionality of facial recognition, testing motion detection response, assessing speech recognition performance in the Institute’s acoustic setting, observing basic system reliability, sampling response times for typical queries from each department, and testing failover during simulated processor situations.

Given the pilot nature of the implementation, these evaluations were performed as formative assessments to pinpoint immediate areas for enhancement instead of serving as summative evaluations of the overall system’s effectiveness. A more comprehensive evaluation framework is planned for future development phases.

Results

Figure 2 presents the completed Badr system installed at the Institute of Learning’s reception desk. The final implementation maintains a professional appearance aligned with institutional branding while incorporating all necessary hardware components within the mannequin’s frame to create a functional AI receptionist system.

Implementation Challenges and Solutions

The development of Badr faced several significant challenges specific to its implementation within the Institute of Learning, which demanded innovative solutions. Hardware reliability was a significant concern, especially considering the need for consistent operation during the Institute’s various departmental activities and events. Initial hardware configurations experienced reliability issues when the Neore Model 3 camera proved incompatible with the Raspberry Pi 5, USB audio devices caused port conflicts, and microSD storage showed signs of potential failure under continuous use.

To address these challenges, the project implemented a more robust hardware configuration designed to meet the Institute’s reliability requirements. The final system utilized a Raspberry Pi 4 for hardware interfaces, replaced individual USB audio devices with a single soundboard, and substituted a high-reliability SSD for microSD storage. These changes enhanced system stability during initial testing, although long-term reliability remains to be assessed and evaluated.

Figure 3 illustrates key phases in Badr’s hardware integration process. These images document the iterative solutions developed to address the compatibility issues, showing the progressive integration of the camera system, computing components, and cooling solutions that were essential to creating a stable platform for the Institute’s reception environment.

Acoustic management presented another significant challenge. The Institute’s reception area has a challenging acoustic environment with variable background noise from learner traffic, nearby classrooms, and departmental activities. This created obstacles to speech recognition and natural language understanding. The solution involved implementing noise filtering algorithms and adaptive gain control to improve audio quality in variable conditions. However, further refinement is needed to address the full range of acoustic scenarios.

Visual privacy concerns also had to be addressed. The Institute’s reception area is a public space where multiple visitors may be present simultaneously, creating potential privacy concerns when displaying or discussing personal information. The solution incorporated directional audio techniques to focus the sound toward the current user and implemented privacy-aware interaction protocols that verify identity before discussing personal information. These measures support compliance with institutional privacy requirements, though additional refinement is needed as the system moves beyond the pilot phase.

Discussion

Addressing the Research Questions

The first research question explored how existing medical simulation mannequins can be effectively repurposed to function as AI-enabled receptionist systems for the Institute of Learning’s four departments. The Badr pilot project demonstrates a promising initial methodology for this transformation, preserving anthropomorphic features while integrating computing hardware, maintaining structural integrity, positioning the mannequin appropriately for reception interactions, adapting internal spaces to accommodate computing and sensing components, and incorporating the Institute’s branding elements. While the implementation is still in the pilot phase, these initial adaptations suggest a viable approach to mannequin repurposing, though further refinement will be necessary for full-scale deployment.

Regarding the second research question on hardware and software architecture that best supports AI receptionist functionalities on resource-constrained computing platforms, the distributed dual-Raspberry Pi architecture shows initial promise. This approach separates hardware interface tasks from AI-intensive processing, enables selective activation of power-intensive components, and provides basic failover capabilities. Early observations suggest that this architecture can support the essential AI functionalities required for departmental interactions, though performance optimization remains an ongoing process.

The third research question investigated the specific adaptations necessary to address the unique reception requirements of the Institute’s departments. The pilot implementation includes initial versions of several specialized adaptations: multilingual capabilities with Arabic dialect support, a departmentally-organized knowledge base, faculty notification systems accommodating academic schedules, visitor categorization specific to the Institute’s organizational structure, integration with key departmental systems, energy efficiency features, and privacy-preserving interaction protocols. These adaptations demonstrate potential for addressing department-specific needs, though user testing across all departments remains limited during this pilot phase.

The fourth research question examined preliminary performance aspects during the pilot phase. Initial testing indicates that Badr can provide basic reception services for the Institute’s departments, with visitor recognition, motion detection, and multilingual communication functionality. However, comprehensive performance evaluation will require extended testing beyond this pilot implementation, particularly regarding long-term reliability, user acceptance across all departments, and comparative effectiveness against traditional reception approaches.

Implications for Institute Operations

The Badr pilot project demonstrates the potential feasibility of implementing AI reception systems for the Institute of Learning through creative repurposing of existing assets. This approach offers several promising advantages for the Institute. Cost-effective implementation by leveraging existing resources represents a significant benefit for the Institute’s budget considerations. The solution aligns with the Institute’s educational mission by extending the utility of teaching equipment beyond traditional simulation contexts. The anthropomorphic presence provides a distinctive and recognizable interface for the Institute’s reception area. The departmentally-structured knowledge base offers potential for consistent information delivery across all four departments.

These initial findings suggest that the Institute of Learning could potentially implement more comprehensive reception automation without the substantial investments typically associated with commercial robotic systems. However, further development and evaluation are necessary to validate this approach. The early results also indicate the potential for the system to serve as an interdepartmental information resource, though this capability requires additional refinement.

Table 2 provides a preliminary comparison of Badr with potential commercial alternatives for academic environments.

Potential Applications Beyond Reception

While Badr was designed primarily as a reception system for the Institute of Learning, the pilot project suggests potential for broader applications across the Institute’s departments. For example, the Healthcare Simulation department could potentially utilize similar technology for enhanced mannequin-based educational scenarios. The Health Professions Education department might explore conversational interfaces for educational assessment and student support. The Organizational Learning department could investigate embodied interfaces for organizational development activities. The Research Center might explore multimodal data collection methodologies using similar sensor integration approaches.

These potential applications suggest that Badr’s repurposing approach could have broader implications for technological integration across the Institute’s departments. However, such extensions would require significant additional development beyond the current pilot implementation.

Limitations and Future Directions

As a pilot implementation, Badr exhibits several limitations that indicate directions for future development. Processing constraints of the current architecture restrict the sophistication of AI components and require further optimization for more complex departmental interactions. Environmental sensitivity affects performance based on lighting and acoustic conditions within the Institute’s reception area. Knowledge base development remains incomplete across all four departments, requiring substantial content development. Initial integration with departmental systems provides limited functionality that requires expansion. User testing has been minimal during this pilot phase, necessitating comprehensive evaluation with diverse visitor types from all departments.

Future directions for the Badr system include refining its multilingual capabilities with expanded Arabic dialect support specific to departmental terminology, enhancing its integration with each department’s information systems, improving speech recognition performance in variable acoustic environments, expanding its knowledge base coverage across all departments, implementing anonymous analytics to identify common departmental information needs, and developing a systematic maintenance and update framework to ensure ongoing functionality. As the system moves beyond the pilot phase, a comprehensive evaluation framework will be essential to assess effectiveness across all four departments.

Conclusion

The Badr AI Receptionist pilot project demonstrates the initial feasibility of repurposing a medical simulation mannequin to create an AI-driven reception system specifically designed for the Institute of Learning and its four departments: Health Professions Education, Healthcare Simulation, Organizational Learning, and the Research Center. By embedding computing capabilities within an anthropomorphic platform, Badr shows potential for providing a unique interface for Institute visitor interactions that leverages existing simulation assets while addressing department-specific information needs.

The project’s preliminary contributions include an initial methodology for repurposing educational simulation equipment for administrative applications, a distributed computing approach that shows promise for balancing performance with cost-effectiveness, and a framework for addressing department-specific reception needs through specialized knowledge organization and interaction patterns.

While still in the pilot phase, with significant development and evaluation needed, the initial implementation suggests that repurposing existing simulation assets could provide a cost-effective approach to enhancing reception services across all Institute departments. The project demonstrates how educational institutions might leverage existing assets to implement AI systems that potentially enhance administrative efficiency and visitor experiences without significant additional investment in purpose-built technologies.

As the Badr system progresses beyond this pilot implementation, comprehensive evaluation across all departments will be essential to determine its effectiveness in meeting the diverse needs of the Institute of Learning’s multidisciplinary environment. The lessons learned from this pilot phase provide valuable direction for subsequent development and potential expansion to other areas of the Institute’s operations.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge the support of the Institute of Learning and its four departments—Health Professions Education, Healthcare Simulation, Organizational Learning, and the Research Center—for providing the facilities, resources, and practical context for this pilot project. We also thank the IoL staff who assisted with the physical adaptation of the medical simulation mannequin and the installation of the system, as well as the administrative staff and departmental representatives who provided valuable feedback during the initial implementation phase.

References

- Bazzano, F., & Lamberti, F. (2018). Human-Robot Interfaces for Interactive Receptionist Systems and Wayfinding Applications. Robotics, 7(3), 56. [CrossRef]

- Samosky, J. T., et al. (2012). BodyExplorerAR: Enhancing a mannequin medical simulator with sensing and projective augmented reality for exploring anatomy, physiology and interventional procedures. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 7282, 220-230.

- Thielen, M. & Delbressine, F. (2016). Rib Cage Recreation: Anatomical Fidelity for Neonatal Mannequins. Journal of Medical and Biological Engineering, 36(3), 329-337.

- Cann, et al. (2020). Sim on a Shoestring: Framework for Low-Cost Procedural Mannequins. Journal of Medical Education and Training, 4(2), 45-52.

- Zary, N., Alfroukh, J., & Alali, M. (2024). Bridging Medical Simulation and Robotics: A Systematic Analysis of Manikin Adaptation for Advanced Applications. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Freire Fiallos, A. A., et al. (2019). A low-cost robotic medical simulator for CPR training. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 575(1), 012019. [CrossRef]

- Freire Fiallos, A. A., et al. (2020). Adaptive sensor integration for robotic medical simulators. IEEE Sensors Journal, 20(15), 8763-8772.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).