Submitted:

24 March 2025

Posted:

25 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Sampling and Granulosa Cell Culture

2.3. Immunofluorescence Staining

2.4. Western Blot Analysis

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

2.6. Flow Cytometric Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

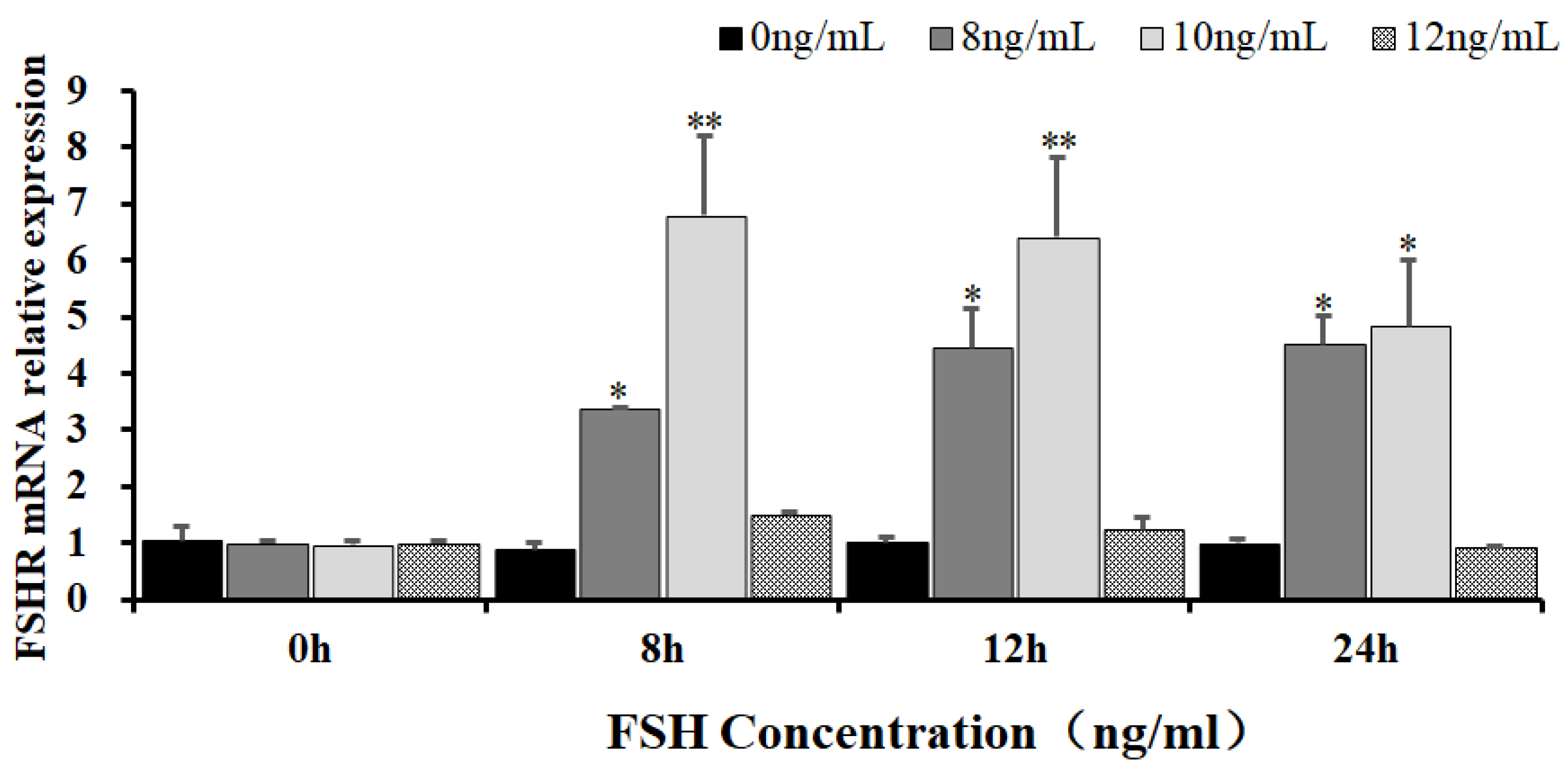

3.1. The Expression of FSHR mRNA in the GCs Regulated by FSH

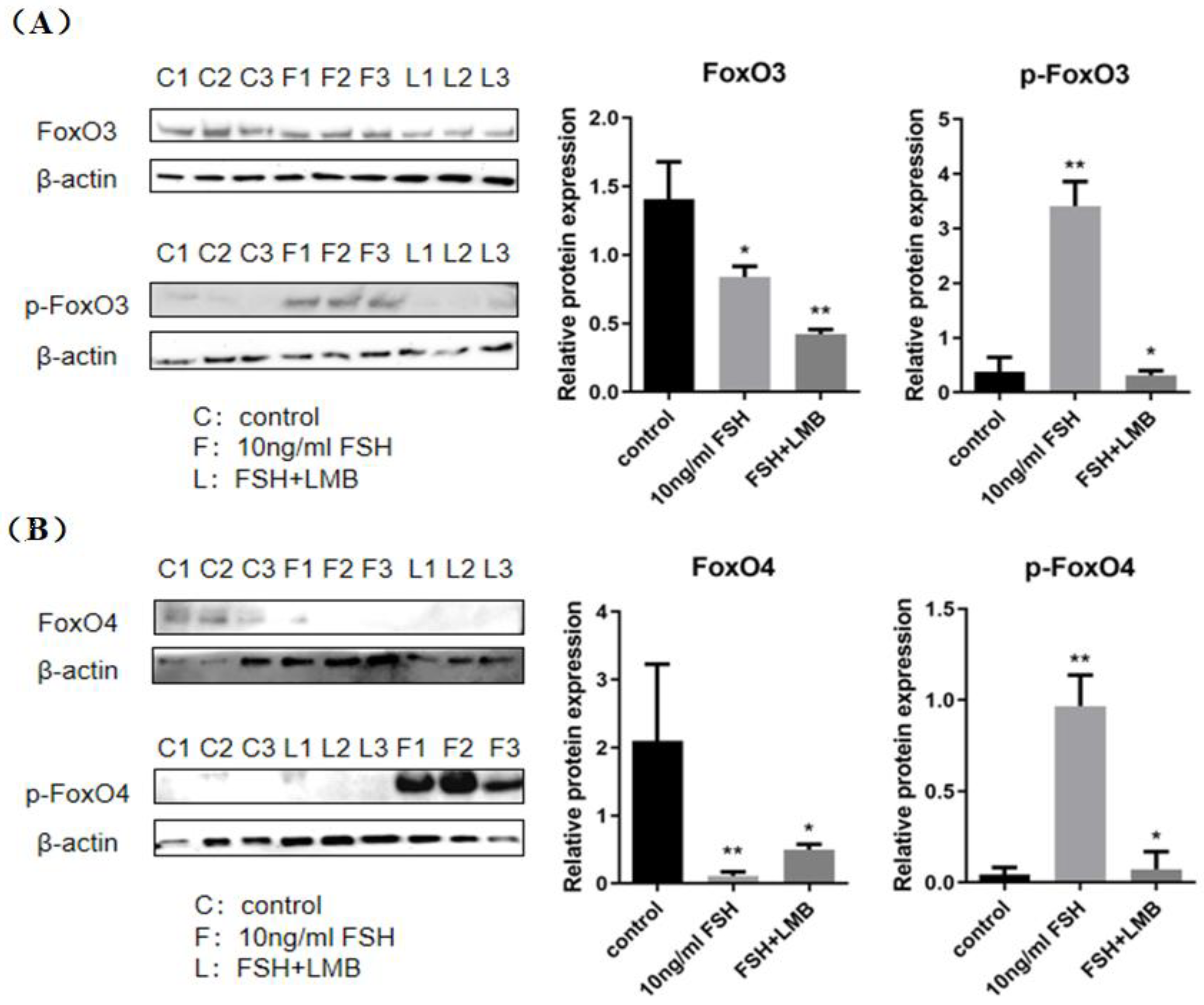

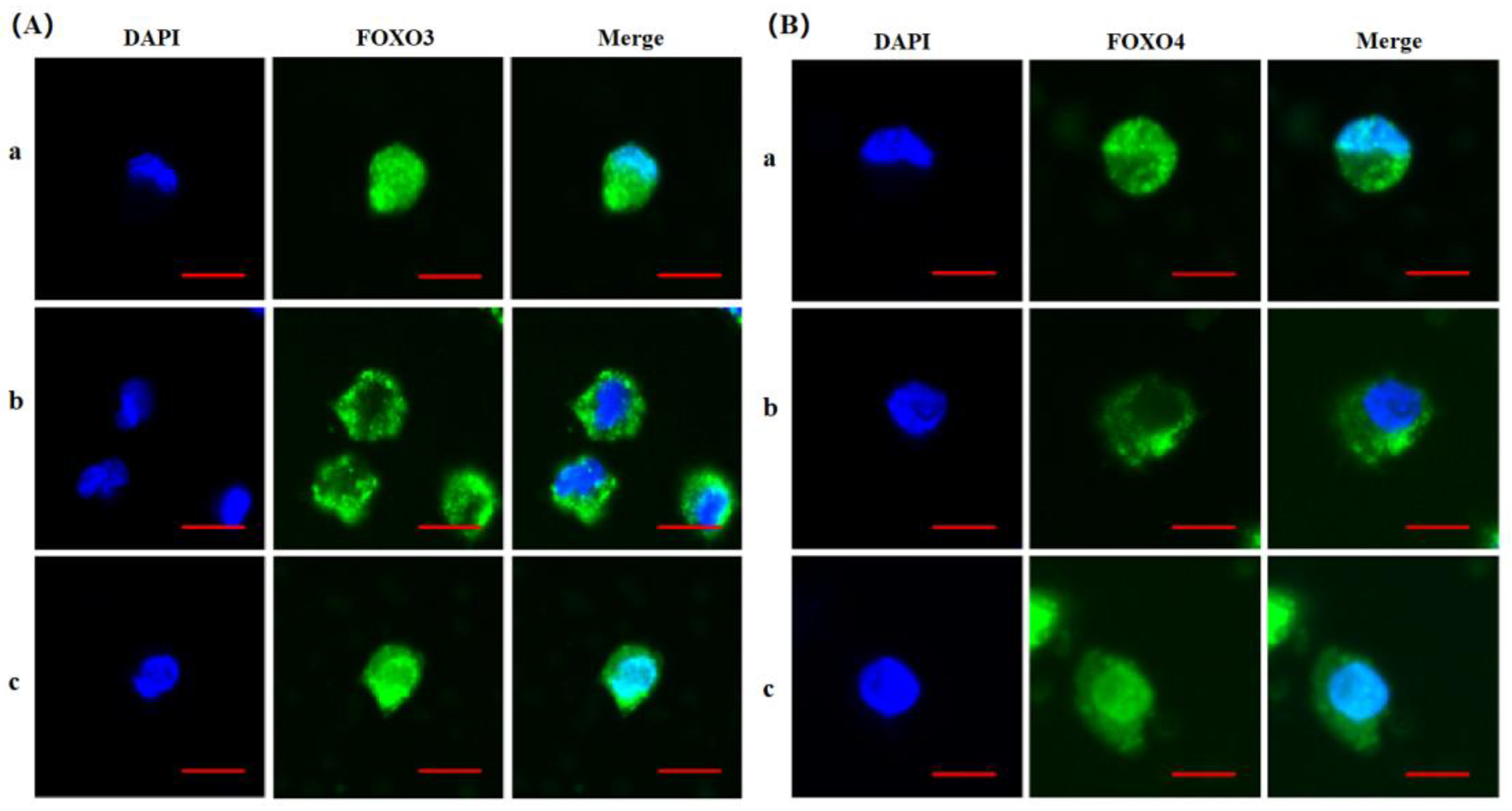

3.2. FoxO3/4 Phosphorylation and Nuclear Exclusion Induced by FSH

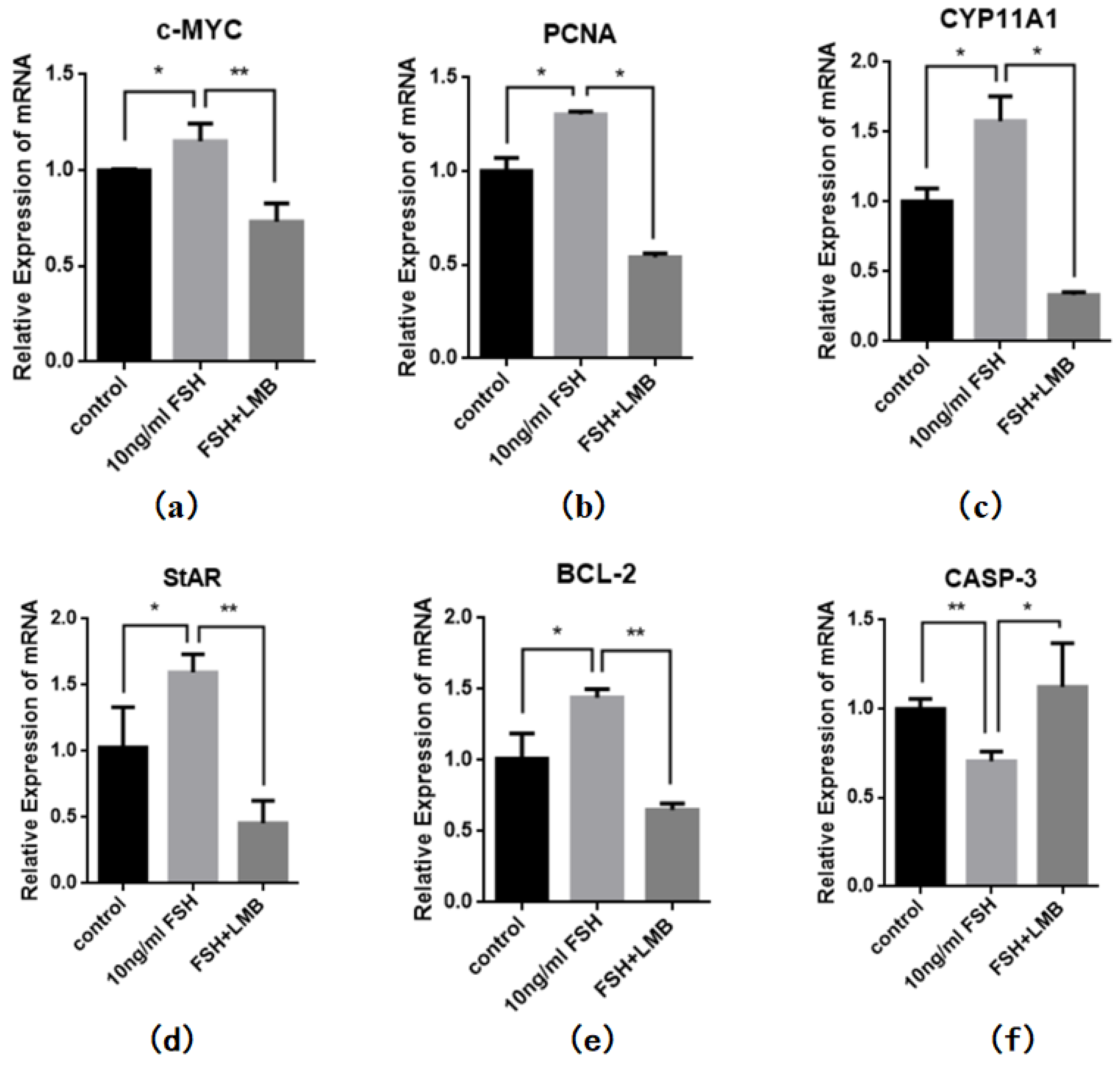

3.3. Expression of the Genes Associated with Cell Proliferation, Differentiation and Apoptosis of the GCs Induced by FSH

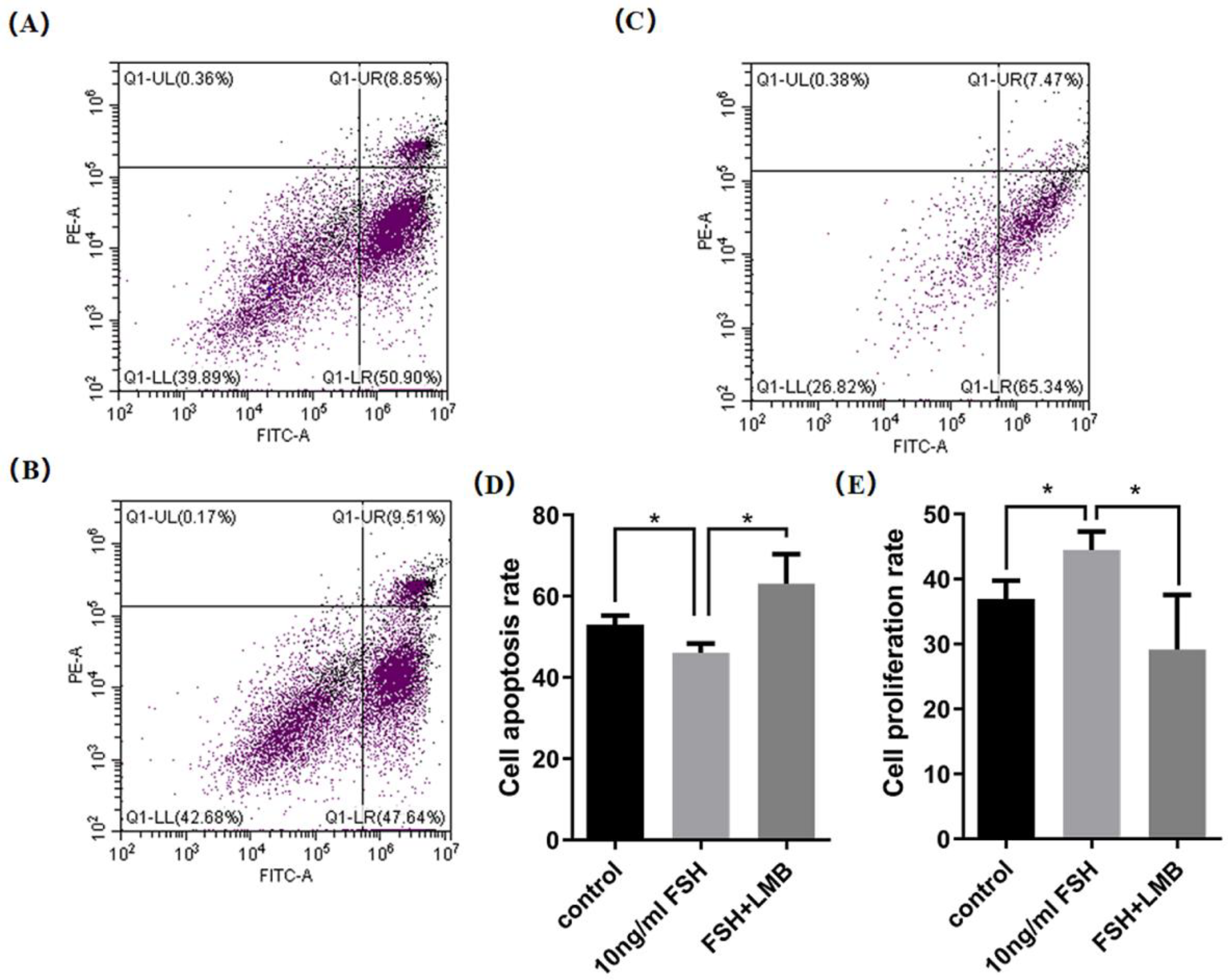

3.4. Effects of FSH-Induced Phosphorylation and Nuclear Exclusion of FoxO3/4 on GCs Proliferation and Apoptosis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, X.; Liswaniso, S.; Shan, X.; Zhao, J.; Chimbaka, I.M.; Xu, R.; et al. The opposite effects of VGLL1 and VGLL4 genes on granulosa cell proliferation and apoptosis of hen ovarian prehierarchical follicles. Theriogenology. 2022, 181, 95-104. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.L.; Woods, D.C. Dynamics of avian ovarian follicle development: cellular mechanisms of granulosa cell differentiation. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2009, 163, 12-17. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.L. Ovarian follicle selection and granulosa cell differentiation. Poult Sci. 2015, 94, 781-785. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Niu, X.; Qin, N.; Shan, X.; Zhao, J.; Ma, C.; et al. Novel insights into the regulation of LATS2 kinase in prehierarchical follicle development via the Hippo pathway in hen ovary. Poult Sci. 2021, 100, 101454. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.L.; Bridgham, J.T. Regulation of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein and luteinizing hormone receptor messenger ribonucleic acid in hen granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 2001, 142, 3116-24. [CrossRef]

- Tilly, J.L.; Kowalski, K.I.; Johnson, A.L. Cytochrome P450 side-chain cleavage (P450scc) in the hen ovary. II. P450scc messenger RNA, immunoreactive protein, and enzyme activity in developing granulosa cells. Biol Reprod. 1991, 45, 967-74. [CrossRef]

- Stocco, D.M. StAR protein and the regulation of steroid hormone biosynthesis. Annu Rev Physiol.2001, 63, 193-213. [CrossRef]

- Morgenbesser, S.D.; Schreiber-Agus, N.; Bidder, M.; Mahon, K.A.; Overbeek, P.A.; Horner, J.; et al. Contrasting roles for c-Myc and L-Myc in the regulation of cellular growth and differentiation in vivo. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 743-56. [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, D.R.; Seo, K.W.; Jung, J.W.; Kim, H.S.; Yang, S.R.; Kang, K.S. The regulatory role of c-MYC on HDAC2 and PcG expression in human multipotent stem cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2011, 15, 1603-14. [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Xin, T.; Nancai, Y.; Yanxia, W.; Qian, L.; Wei, M.; et al. Short-interfering RNA-mediated silencing of proliferating cell nuclear antigen inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in HeLa cells. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008, 18, 36-42. [CrossRef]

- Strzalka, W.; Ziemienowicz, A. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA): a key factor in DNA replication and cell cycle regulation. Ann Bot. 2011, 107, 1127-40. [CrossRef]

- Tsujimoto, Y. Role of Bcl-2 family proteins in apoptosis: apoptosomes or mitochondria? Genes Cells. 1998, 3, 697-707. [CrossRef]

- Ola, M.S.; Nawaz, M.; Ahsan, H. Role of Bcl-2 family proteins and caspases in the regulation of apoptosis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011, 351, 41-58. [CrossRef]

- Tilly, J.L.; LaPolt, P.S.; Hsueh, A.J. Hormonal regulation of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor messenger ribonucleic acid levels in cultured rat granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 1992, 130, 1296-302. [CrossRef]

- Woods, D.C.; Johnson, A.L. Regulation of follicle-stimulating hormone-receptor messenger RNA in hen granulosa cells relative to follicle selection. Biol Reprod. 2005, 72, 643-50. [CrossRef]

- de Souza, D.K.; Salles, L.P.; Camargo, R.; Gulart, L.V.M.; Costa, E. Silva, S.; de Lima, B.D.; et al. Effects of PI3K and FSH on steroidogenesis, viability and embryo development of the cumulus-oocyte complex after in vitro culture. Zygote. 2018, 26, 50-61. [CrossRef]

- Urban, R.J.; Garmey, J.C.; Shupnik, M.A.; Veldhuis, J.D. Follicle-stimulating hormone increases concentrations of messenger ribonucleic acid encoding cytochrome P450 cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme in primary cultures of porcine granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 1991, 128, 2000-2007. [CrossRef]

- Bhartiya, D.; Patel, H. An overview of FSH-FSHR biology and explaining the existing conundrums. J Ovarian Res. 2021, 14, 144. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.H.; Chen, J.L.; Xu, H.; Liu, J.W.; Xu, R.F. Cloning and Expression of FSHb Gene and the Effect of FSH on the mRNA Levels of FSHR in the Local Chicken. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences. 2010, 23, 292-301.

- Johnson, A.L.; Lee, J. Granulosa cell responsiveness to follicle stimulating hormone during early growth of hen ovarian follicles. Poult Sci. 2016, 95, 108-14. [CrossRef]

- Sassone-Corsi, P. Coupling gene expression to cAMP signalling: role of CREB and CREM. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1998, 30, 27-38. [CrossRef]

- Francis, S.H.; Corbin, J.D. Cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases: intracellular receptors for cAMP and cGMP action. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1999, 36, 275-328. [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Kumar, T.R. Molecular regulation of follicle-stimulating hormone synthesis, secretion and action. J Mol Endocrinol. 2018, 60, R131-55. [CrossRef]

- Casarini, L.; Crépieux, P. Molecular Mechanisms of Action of FSH. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019, 10, 305. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, F.; Inoue, N.; Maeda, A.; Cheng, Y.; Sai, T.; Gonda, H.; et al. Expression and function of apoptosis initiator FOXO3 in granulosa cells during follicular atresia in pig ovaries. J Reprod Dev. 2011, 57, 151-8. [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Lin, F.; Zhang, J.; Tang, Y.; Chen, W.K.; Liu, H. Involvement of the up-regulated FoxO1 expression in follicular granulosa cell apoptosis induced by oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2012, 287, 25727-40. [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Han, S.; Yin, H.; Luo, B.; Shen, X.; Yang, F.; et al. FOXO3 is expressed in ovarian tissues and acts as an apoptosis initiator in granulosa cells of chickens. Biomed Res Int. 2019, 6902906. [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Lin, F.; Zhang, J.; Tang, Y.; Chen, W.K.; Liu, H. Involvement of the up-regulated FoxO1 expression in follicular granulosa cell apoptosis induced by oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2012, 287, 25727-40. [CrossRef]

- Mikaeili, S.; Rashidi, B.H.; Safa, M.; Najafi, A.; Sobhani, A.; Asadi, E.; et al. Altered FoxO3 expression and apoptosis in granulosa cells of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016, 294, 185-92. [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.Y.; Eisenhauer, K.M.; Minami, S.; Billig, H.; Perlas, E.; Hsueh, A.J. Hormonal regulation of apoptosis in early antral follicles: follicle-stimulating hormone as a major survival factor. Endocrinology. 1996; 1447-56. [CrossRef]

- Hunzicker-Dunn, M.; Maizels, E.T. FSH signaling pathways in immature granulosa cells that regulate target gene expression: branching out from protein kinase A. Cell Signal. 2006, 18, 1351-9. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Tindall, D.J. Dynamic FoxO transcription factors. J Cell Sci. 2007, 120, 2479-87. [CrossRef]

- de Keizer, P.L.; Burgering, B.M.; Dansen, T.B. Forkhead box o as a sensor, mediator, and regulator of redox signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011, 14, 1093-106. [CrossRef]

- Herndon, M.K.; Law, N.C.; Donaubauer, E.M.; Kyriss, B.; Hunzicker-Dunn, M. Forkhead box O member FOXO1 regulates the majority of follicle-stimulating hormone responsive genes in ovarian granulosa cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016, 434, 116-26. [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Liu, Z.; Li, B.; Teng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tang, Y.; et al. Involvement of FoxO1 in the effects of follicle-stimulating hormone on inhibition of apoptosis in mouse granulosa cells. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1475. [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.S.; Russell, D.L.; Ochsner, S.; Hsieh, M.; Doyle, K.H.; Falender, A.E.; et al. Novel signaling pathways that control ovarian follicular development, ovulation, and luteinization. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2002, 57, 195-220. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, P.H.; Hu, W. Overexpression of FOXO4 induces apoptosis of clear-cell renal carcinoma cells through downregulation of Bim. Mol Med Rep. 2016, 13, 2229-34. [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, S.; Yang, Y.; Han, Y.; Lv, J.; et al. Forkhead box O4 transcription factor in human neoplasms: Cannot afford to lose the novel suppressor. J Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 8647-58. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Luo, B. Current perspective on the regulation of FOXO4 and its role in disease progression. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2020, 77, 651-63. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Heide, L.P.; Hoekman, M.F.; Smidt, M.P. The ins and outs of FoxO shuttling: mechanisms of FoxO translocation and transcriptional regulation. Biochem J. 2004, 380, 297-309. [CrossRef]

- Santos, B. F.; Grenho, I.; Martel, P. J.; Ferreira, B. I.; Link, W. FOXO family isoforms. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 702. [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, H.; Ichino, A.; Hayashi, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Kikkawa, U. Regulation of intracellular localization and transcriptional activity of FOXO4 by protein kinase B through phosphorylation at the motif sites conserved among the FOXO family. J Biochem. 2005, 138, 485–491. [CrossRef]

- Lüpertz, R.; Chovolou, Y.; Unfried, K.; Kampkötter, A.; Wätjen, W.; Kahl, R. The forkhead transcription factor FOXO4 sensitizes cancer cells to doxorubicin-mediated cytotoxicity. Carcinogenesis. 2008, 29, 2045–2052. [CrossRef]

- Manning, B. D.; Cantley, L. C. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007, 129, 1261–1274. [CrossRef]

- Essers, M. A.; Weijzen, S.; de Vries-Smits, A. M.; Saarloos, I.; de Ruiter, N. D.; Bos, J. L.; Burgering, B. M. FOXO transcription factor activation by oxidative stress mediated by the small GTPase Ral and JNK. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 4802–4812. [CrossRef]

- van der Horst, A.; de Vries-Smits, A. M.; Brenkman, A. B.; van Triest, M. H.; van den Broek, N.; Colland, F.; Maurice, M. M.; Burgering, B. M. FOXO4 transcriptional activity is regulated by monoubiquitination and USP7/HAUSP. Nat Cell Biol. 2006, 8, 1064–1073. [CrossRef]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M. T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W. J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I. C.; Dirnagl, U.; Emerson, M.; et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Qin, N.; Xu, X.; Sun, X.; Chen, X.; Zhao, J. Inhibitory effect of SLIT2 on granulosa cell proliferation mediated by the CDC42-PAKs-ERK1/2 MAPK pathway in the prehierarchical follicles of the chicken ovary. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 9168. [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, R. B.; Ritter, L. J.; Myllymaa, S.; Kaivo-Oja, N.; Dragovic, R. A.; Hickey, T. E.; Ritvos, O.; Mottershead, D. G. Molecular basis of oocyte-paracrine signalling that promotes granulosa cell proliferation. J Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 3811-21. 3811–3821. [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, T. K.; Shea, L. D. The role of the extracellular matrix in ovarian follicle development. Reprod Sci. 2007, 14, 6-10. [CrossRef]

- Dias, J. A.; Campo, B.; Weaver, B. A.; Watts, J.; Kluetzman, K.; Thomas, R. M.; Bonnet, B.; Mutel, V.; Poli, S. M. Inhibition of follicle-stimulating hormone-induced preovulatory follicles in rats treated with a nonsteroidal negative allosteric modulator of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor. Biol Reprod. 2014, 90, 19. [CrossRef]

- Rimon-Dahari, N.; Yerushalmi-Heinemann, L.; Alyagor, L.; Dekel, N. Ovarian Folliculogenesis. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2016, 58, 167-90. [CrossRef]

- Ulloa-Aguirre, A.; Zariñán, T.; Pasapera, A. M.; Casas-González, P.; Dias, J. A. Multiple facets of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor function. Endocrine. 2007, 32, 251-63. [CrossRef]

- You, S.; Bridgham, J. T.; Foster, D. N.; Johnson, A. L. Characterization of the chicken follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (cFSH-R) complementary deoxyribonucleic acid, and expression of cFSH-R messenger ribonucleic acid in the ovary. Biol Reprod. 1996, 55, 1055-62. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Ocón-Grove, O.; Johnson, A. L. Bone morphogenetic protein 4 supports the initial differentiation of hen (Gallus gallus) granulosa cells. Biol Reprod. 2013, 88, 161. [CrossRef]

- Li GY. Regulating effect of FSH on apoptosis, secretion of cytokines and genes expression by FSHR/cAMP/Foxo3a of yak follicular granulosa cells. Lanzhou: Doctoral Dissertation of Gansu Agricultural University. 2017 (in Chinese).

- Zheng MX. The research of follicle stimulating hormone regulates the expression of stem cell factor in granulosa cells to promote the follicular development. Yinchuan: Master Dissertation of Ningxia Medical University. 2017 (in Chinese).

- Wang YY. Effects of FSH on gene expression related to steroidogenesis in bovine follicles cultured in vitro. Beijing: Master Dissertation of the Institute of Animal Science of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. 2019 (in Chinese).

- Chen X. Study on difference of ovulation effect induced by FSH in sheep. Hohhot: Master Dissertation of Inner Mongolia University. 2021 (in Chinese).

- Link W. Introduction to FOXO Biology. Methods Mol Biol. 2019, 1890, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Miao, S.; Zhou, W.; Elnesr, S. S.; Dong, X.; Zou, X. Corrigendum to: “MAPK, AKT/FoxO3a and mTOR pathways are involved in cadmium regulating the cell cycle, proliferation and apoptosis of chicken follicular granulosa cells” [Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 214 (2021) 112091]. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021, 214, 112091. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xi, Y.; Li, M.; Wu, Y.; Yan, W.; Dai, J.; Wu, M.; Ding, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, S.; Wang, S. Maternal exposure to PM2.5 decreases ovarian reserve in neonatal offspring mice through activating PI3K/AKT/FoxO3a pathway and ROS-dependent NF-κB pathway. Toxicology. 2022, 481, 153352. [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.; Su, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, K.; Fu, R.; Sui, S. Signaling pathways of Periplaneta americana peptide resist H2O2-induced apoptosis in pig-ovary granulosa cells through FoxO1. Theriogenology. 2022, 183, 108-19. [CrossRef]

- Ting, A. Y.; Zelinski, M. B. Characterization of FOXO1, 3 and 4 transcription factors in ovaries of fetal, prepubertal and adult rhesus macaques. Biol Reprod. 2017, 96, 1052-9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ao, X.; Ding, W.; Ponnusamy, M.; Wu, W.; Hao, X.; Yu, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, J. Critical role of FOXO3a in carcinogenesis. Mol Cancer. 2018, 17, 104. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liu, J.; Bao, D.; Hu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, S. Progress in the study of FOXO3a interacting with microRNA to regulate tumourigenesis development. Front Oncol. 2023, 13, 1293968. [CrossRef]

- Brownawell, A. M.; Kops, G. J.; Macara, I. G.; Burgering, B. M. Inhibition of nuclear import by protein kinase B (Akt) regulates the subcellular distribution and activity of the forkhead transcription factor AFX. Mol Cell Biol. 2001, 21, 3534-46. [CrossRef]

- Rena, G.; Woods, Y. L.; Prescott, A. R.; Peggie, M.; Unterman, T. G.; Williams, M. R.; Cohen, P. Two novel phosphorylation sites on FKHR that are critical for its nuclear exclusion. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 2263-71. [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, M.; Asano, S.; Nakamura, T.; Adachi, M.; Yoshida, M.; Yanagida, M.; Nishida, E. CRM1 is responsible for intracellular transport mediated by the nuclear export signal. Nature. 1997, 390, 308-11. [CrossRef]

- Kudo, N.; Wolff, B.; Sekimoto, T.; Schreiner, E. P.; Yoneda, Y.; Yanagida, M.; Horinouchi, S.; Yoshida, M. Leptomycin B inhibition of signal-mediated nuclear export by direct binding to CRM1. Exp Cell Res. 1998, 242, 540-47. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Fukuda, M.; Yoshida, M.; Yanagida, M.; Nishida, E. Involvement of CRM1, a nuclear export receptor, in mRNA export in mammalian cells and fission yeast. Genes Cells.1999, 4, 291-97. [CrossRef]

- Vogt, P. K.; Jiang, H.; Aoki, M. Triple layer control: phosphorylation, acetylation and ubiquitination of FOXO proteins. Cell Cycle. 2005, 4, 908-13. [CrossRef]

- Obsilova, V.; Vecer, J.; Herman, P.; Pabianova, A.; Sulc, M.; Teisinger, J.; Boura, E.; Obsil, T. 14-3-3 Protein interacts with nuclear localization sequence of forkhead transcription factor FoxO4. Biochemistry. 2005, 44, 11608-17. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M. D.; Luo, X.; Biteau, B.; Syverson, K.; Jasper, H. 14-3-3 Epsilon antagonizes FoxO to control growth, apoptosis and longevity in Drosophila. Aging Cell. 2008, 7, 688-99. [CrossRef]

- Zanella, F.; Rosado, A.; García, B.; Carnero, A.; Link, W. Chemical genetic analysis of FOXO nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling by using image-based cell screening. Chembiochem. 2008, 9, 2229-37. [CrossRef]

- Mutka, S. C.; Yang, W. Q.; Dong, S. D.; Ward, S. L.; Craig, D. A.; Timmermans, P. B.; Murli, S. Identification of nuclear export inhibitors with potent anticancer activity in vivo. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 510-7. [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, K.; Dean, D. A. Leptomycin B alters the subcellular distribution of CRM1 (Exportin 1). Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017, 488, 253-8. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Kong, D.; Li, R.; Sarkar, S. H.; Sarkar, F. H. Regulation of Akt/FOXO3a/GSK-3beta/AR signaling network by isoflavone in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2008, 283, 27707-16. [CrossRef]

- Charvet, C.; Alberti, I.; Luciano, F.; Jacquel, A.; Bernard, A.; Auberger, P.; Deckert, M. Proteolytic regulation of Forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a by caspase-3-like proteases. Oncogene. 2003, 22, 4557-68. [CrossRef]

| Gene | Forward primer(5’-3’) | Reverse primer(5’-3’) | Accession No. | Size |

| FSHR | ATGTCTCCGGCAAAGCAAGA | AACGACTTCGTTGCACAAGC | NM_205079.1 | 147 bp |

| CASP-3 | ATTGAAGCAGACAGTGGACCAGATG | TGCGTTCCTCCAGGAGTAGTAGC | NM_204725.2 | 111 bp |

| PCNA | CTGAGGCGTGCTGGG | ATGGCGATGTTGCGG | NM_204170.3 | 133 bp |

| StAR | AGCAGATGGGCGACTGGAAC | GGGAGCACCGAACACTCACAA | NM_204686.2 | 147 bp |

| CYP11A1 | CCGCTTTGCCTTGGAGTCTGTG | ATGAGGGTGACGGCGTCGATGAA | NM_001001756.1 | 111 bp |

| c-MYC | GAGAACGACAAGAGGCGAAC | CGCCTCAACTGCTCTTTCTC | NM_001030952.2 | 211 bp |

| BCL-2 | CGCTACCAGAGGGAC | GAAGAAGGCGACGAT | NM_205339.3 | 135 bp |

| PDK1 | AGACATCCCGAGCTACACCT | CGCCTTGGAAGTATTGTGCG | NM_001031352.4 | 81bp |

| SGK3 | TGCGTCCAGGAATCAGTCTCAC | AAGTCTGCTTTGCCGATCTTTCTC | NM_001030940.2 | 74bp |

| 18s rRNA | TAGTTGGTGGAGCGATTTGTCT | CGGACATCTAAGGGCATCACA | AF173612.1 | 169 bp |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).