Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Farms and Animals

2.2. Milk Sample Collection

2.3. Milk Chemical Composition, Milk Physical Properties, SCC and TBC

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

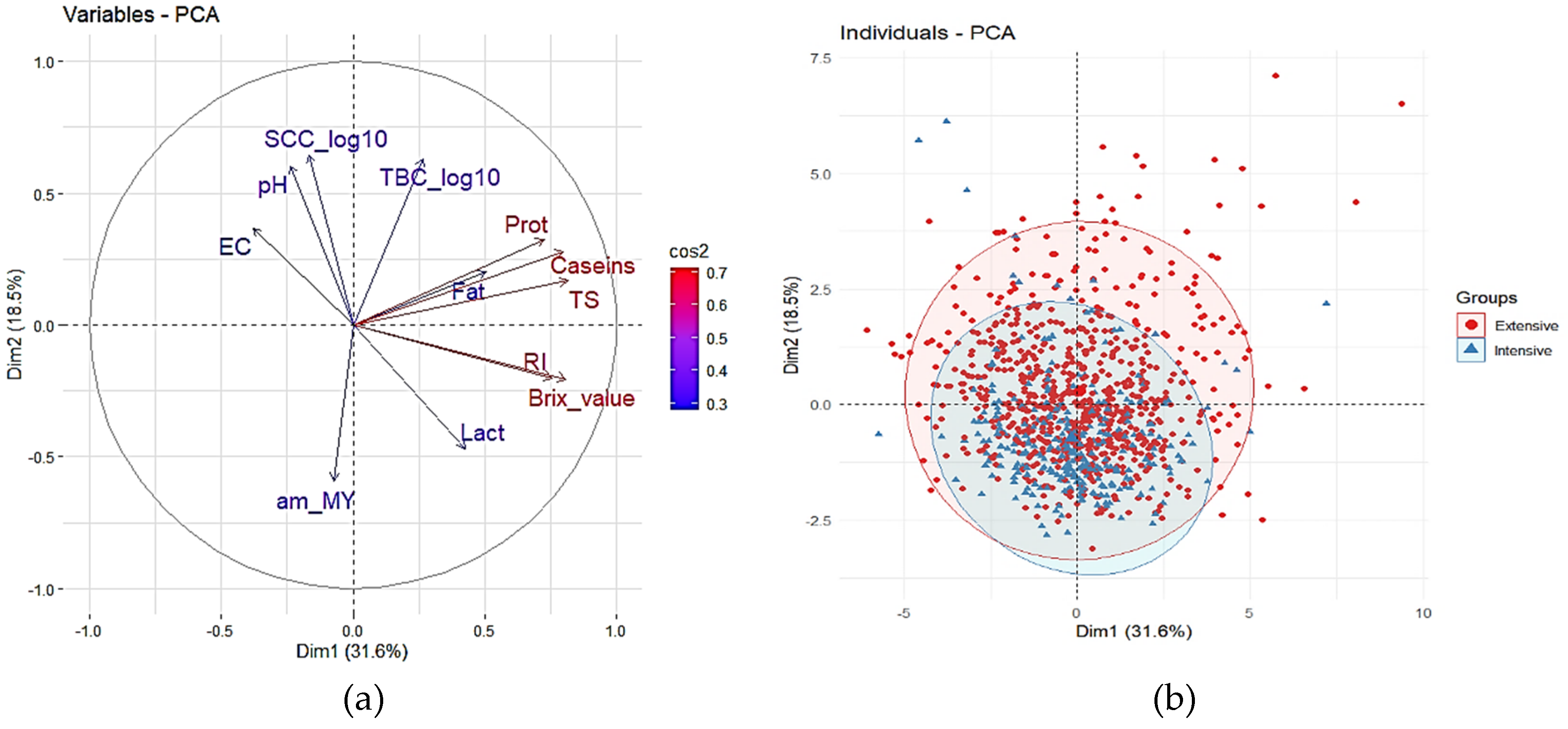

3.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

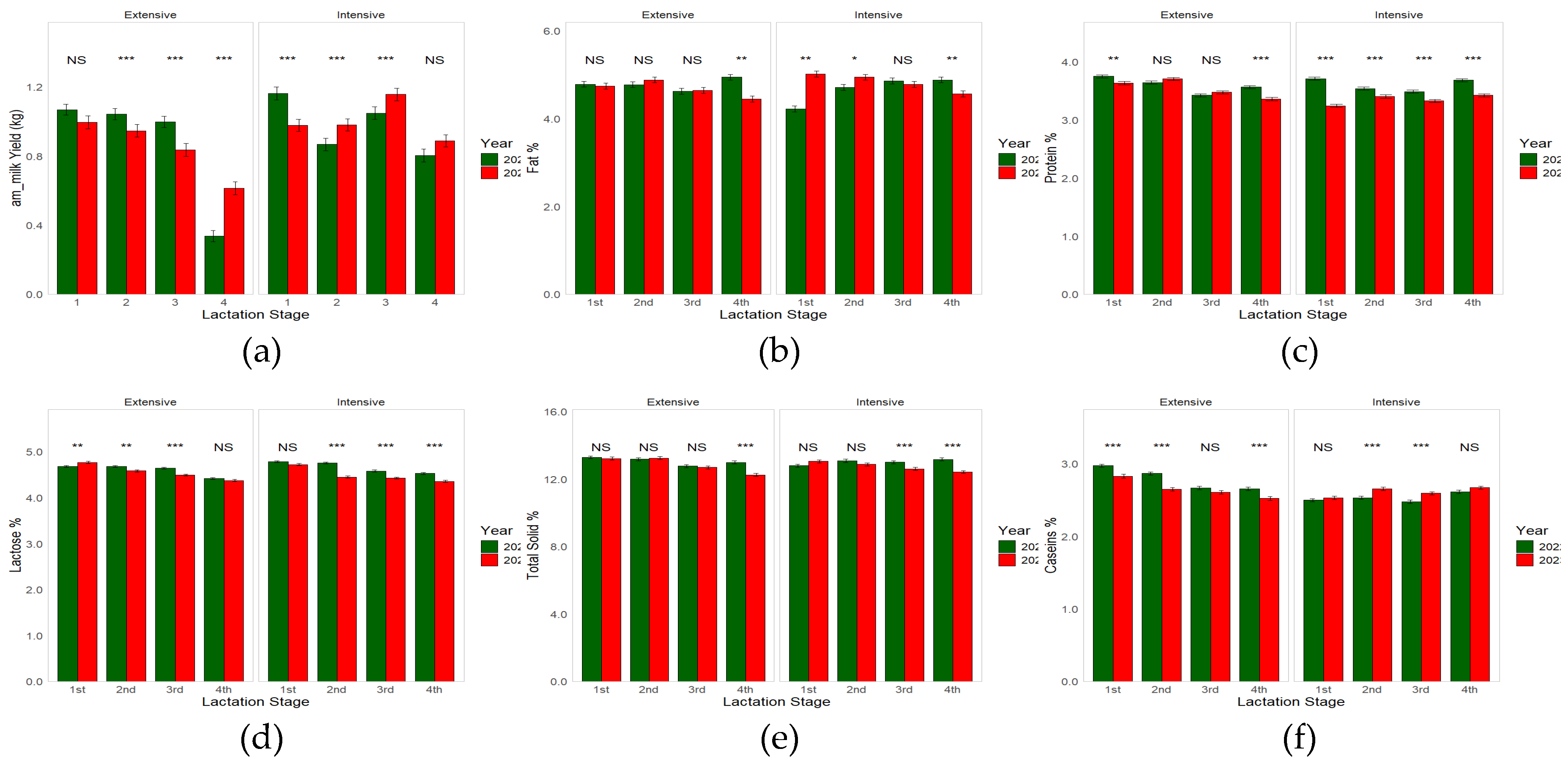

3.2. Effect of Farming System, and Lactation Stage on Milk Yield and Composition Across the Two Lactation Periods

3.3. Effect of Farming System, Year and LS on Milk Physical Properties, SCC and TBC

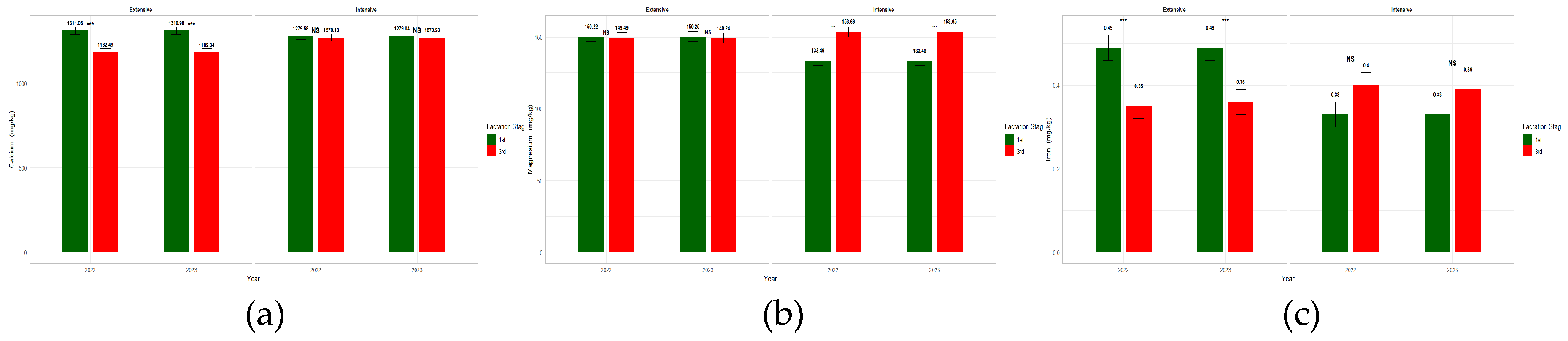

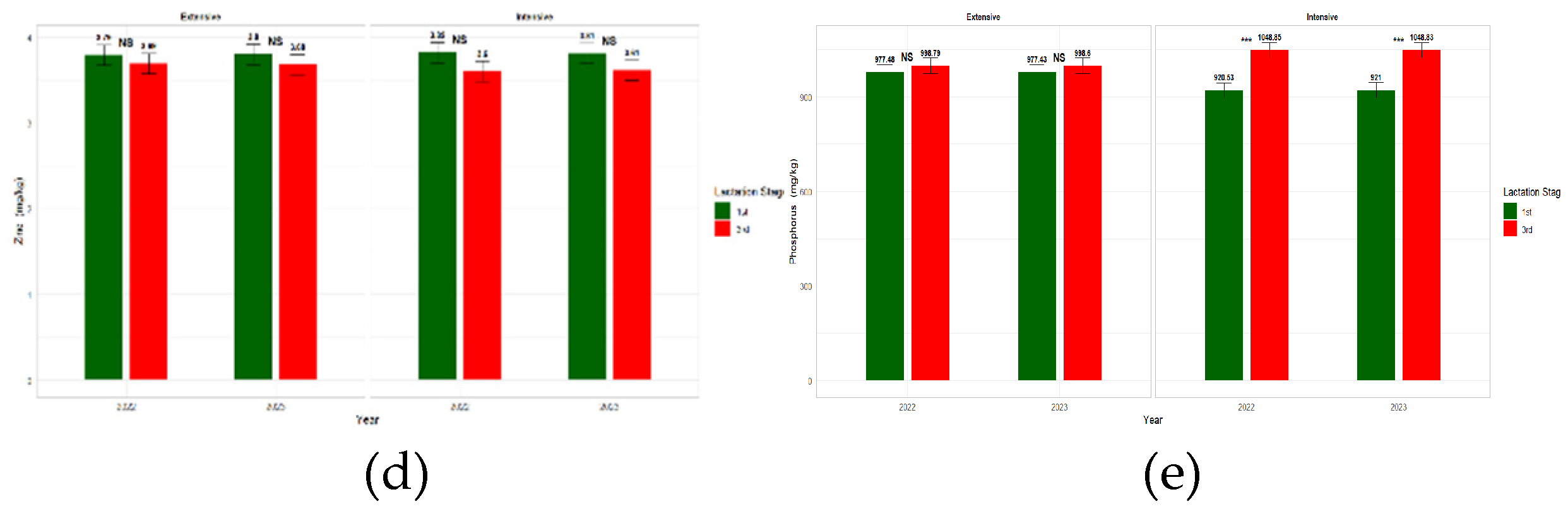

3.4. Effect of Farming System, Year and LS on Milk Mineral Content

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DIM | Days in milk |

| PCA | Principal components analysis |

| am_MY | Am milk yield |

| LS | Lactation stage |

| TS | Total Solid |

| CAS | Total Casein |

| EC | Electrical Conductivity |

| RI | Refractive Index |

| SCC | Somatic Cell Count |

| TBC | Total Bacterial Count |

References

- Pulina, G.; Milán, M.J.; Lavín, M.P.; Theodoridis, A.; Morin, E.; Capote, J.; Thomas, D.L.; Francesconi, A.H.D.; Caja, G. Invited Review: Current Production Trends, Farm Structures, and Economics of the Dairy Sheep and Goat Sectors. Journal of Dairy Science 2018, 101, 6715–6729. [CrossRef]

- Dubeuf, J.-P.; Ruiz Morales, F.D.A.; Guerrero, Y.M. Evolution of Goat Production Systems in the Mediterranean Basin: Between Ecological Intensification and Ecologically Intensive Production Systems. Small Ruminant Research 2018, 163, 2–9. [CrossRef]

- Arsenos, G.; Gelasakis, A.; Pinopoulos, S.; Giannakou, R.; Amarantidis, I. Description and Typology of Dairy Goat Farms in Greece. 2014.

- Lopez, A.; Vasconi, M.; Battini, M.; Mattiello, S.; Moretti, V.M.; Bellagamba, F. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Quality Attributes of Fresh and Semi-Hard Goat Cheese from Low- and High-Input Farming Systems. Animals 2020, 10, 1567. [CrossRef]

- Getaneh G.; Mebrat A.; Wubie A.; Kendie H. Review on Goat Milk Composition and Its Nutritive Value. Journal of Nutrition and Health Sciences 2016, 3. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Jeanjulien, C.; Siddique, A. Factors Affecting Sensory Quality of Goat Milk Cheeses: A Review. J Adv Dairy Res 2017, 05. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi Comforts in Quality and Production of Goat Milk. J Adv Dairy Res 2015, 03. [CrossRef]

- Cyrilla, L.; Purwanto, B.P.; Atabany, A.; Astuti, D.A.; Sukmawati, A. Improving Milk Quality for Dairy Goat Farm Development. Med Pet 2015, 38, 204–211. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. Improving Goat Milk. In Improving the Safety and Quality of Milk; Elsevier, 2010; pp. 304–346 ISBN 978-1-84569-806-5.

- Cruz, A.V.D.; Oliveira, A.L.B.D.; Silva, B.D.S.D.; Silva, E.A.C.D.; Lima, A.L.A. Physicochemical and Microbiological Aspects of Goat Milk. Rev. Sci. Agr. Paranaensis 2021, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Tzamaloukas, O.; Neofytou, M.C.; Simitzis, P.E.; Miltiadou, D. Effect of Farming System (Organic vs. Conventional) and Season on Composition and Fatty Acid Profile of Bovine, Caprine and Ovine Milk and Retail Halloumi Cheese Produced in Cyprus. Foods 2021, 10, 1016. [CrossRef]

- Paskaš, S. The Influence of Grazing and Indoor Systems on Goat Milk, Brined Cheese and Whey Quality. Mljekarstvo 2023, 73, 143–154. [CrossRef]

- Kucevic, D.; Pihler, I.; Plavsic, M.; Vukovic, T. The Composition of Goat Milk in Different Types of Farmings. Bio Anim Husb 2016, 32, 403–412. [CrossRef]

- Pazzola, M.; Amalfitano, N.; Bittante, G.; Dettori, M.L.; Vacca, G.M. Composition, Coagulation Properties, and Predicted Cheesemaking Traits of Bulk Goat Milk from Different Farming Systems, Breeds, and Stages of Production. Journal of Dairy Science 2022, 105, 6724–6738. [CrossRef]

- Kyozaire, J.K.; Veary, C.M.; Petzer, I.-M.; Donkin, E.F. Microbiological Quality of Goat’s Milk Obtained under Different Production Systems. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2005, 76, 69–73. [CrossRef]

- ISO:Milk and Liquid Milk Products, Guidelines for the Application of Mid-Infrared Spectrometry. In International Standard ISO 9622: 2013/IDF 141: 2013. International Dairy Federation; 2013.

- European Standard EN 16943:2017 Foodstuffs - Determination of Calcium, Copper, Iron, Magnesium, Manganese, Phos-Phorus, Potassium, Sodium, Sulfur and Zinc by ICP-OES. 2017.

- AOAC Official Method 2011.14 Calcium, Copper, Iron, Magnesium, Manganese, Po-Tassium, Phosphorus, Sodium, and Zinc in Fortified Food Products Microwave Digestion and Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectrometry. 2011.

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing_. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. <https://Www.R-Project.Org/ 2024.

- Kassambara, A. and Mundt, F. Factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses. R Package Version 1.0.7. Https://CRAN.R-Project.Org/Package=factoextra.

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Soft. 2008, 25. [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Lme4. J. Stat. Soft. 2015, 67. [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, Aka Least-Squares Means. R Package Version 1.8.5, Https://CRAN.R-Project.Org/Package=emmeans. 2023.

- Currò, S.; Manuelian, C.; De Marchi, M.; Claps, S.; Rufrano, D.; Neglia, G. Effects of Breed and Stage of Lactation on Milk Fatty Acid Composition of Italian Goat Breeds. Animals 2019, 9, 764. [CrossRef]

- El-Tarabany, M.S.; El-Tarabany, A.A.; Roushdy, E.M. Impact of Lactation Stage on Milk Composition and Blood Biochemical and Hematological Parameters of Dairy Baladi Goats. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2018, 25, 1632–1638. [CrossRef]

- Morand-Fehr, P.; Fedele, V.; Decandia, M.; Le Frileux, Y. Influence of Farming and Feeding Systems on Composition and Quality of Goat and Sheep Milk. Small Ruminant Research 2007, 68, 20–34. [CrossRef]

- Goetsch, A.L.; Zeng, S.S.; Gipson, T.A. Factors Affecting Goat Milk Production and Quality. Small Ruminant Research 2011, 101, 55–63. [CrossRef]

- Kawas, J.R.; Lopes, J.; Danelon, D.L.; Lu, C.D. Influence of Forage-to-Concentrate Ratios on Intake, Digestibility, Chewing and Milk Production of Dairy Goats. Small Ruminant Research 1991, 4, 11–18. [CrossRef]

- Isidro-Requejo, L.M.; Meza-Herrera, C.A.; Pastor-López, F.J.; Maldonado, J.A.; Salinas-González, H. Physicochemical Characterization of Goat Milk Produced in the Comarca Lagunera, Mexico. Animal Science Journal 2019, 90, 563–573. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.S.; Escobar, E.N. Effect of Breed and Milking Method on Somatic Cell Count, Standard Plate Count and Composition of Goat Milk. Small Ruminant Research 1996, 19, 169–175. [CrossRef]

- Bär, C.; Sutter, M.; Kopp, C.; Neuhaus, P.; Portmann, R.; Egger, L.; Reidy, B.; Bisig, W. Impact of Herbage Proportion, Animal Breed, Lactation Stage and Season on the Fatty Acid and Protein Composition of Milk. International Dairy Journal 2020, 109, 104785. [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, D.P.; Mohapatra, S.; Misra, S.; Sahu, P.S. Milk Derived Bioactive Peptides and Their Impact on Human Health – A Review. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2016, 23, 577–583. [CrossRef]

- Inglingstad, R.A.; Steinshamn, H.; Dagnachew, B.S.; Valenti, B.; Criscione, A.; Rukke, E.O.; Devold, T.G.; Skeie, S.B.; Vegarud, G.E. Grazing Season and Forage Type Influence Goat Milk Composition and Rennet Coagulation Properties. Journal of Dairy Science 2014, 97, 3800–3814. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.S.; Jiang, H.; Wang, C.F.; Cheng, M.; Wang, L.L.; Huang, M.Y.; Zhao, Q.X.; Jiang, H.H. Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Goat Milk Whey Protein and Casein Obtained during Different Lactation Stages. Journal of Dairy Science 2021, 104, 3936–3946. [CrossRef]

- Canul-Medina, G.; Fernandez-Mejia, C. Morphological, Hormonal, and Molecular Changes in Different Maternal Tissues during Lactation and Post-Lactation. J Physiol Sci 2019, 69, 825–835. [CrossRef]

- Oppat, C.A.; Rillema, J.A. Characteristics of the Early Effect of Prolactin on Lactose Biosynthesis in Mouse Mammary Gland Explants. Experimental Biology and Medicine 1988, 188, 342–345. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, F.; Massouras, T.; Barbosa, M.; Roseiro, L.; Ravasco, F.; Kandarakis, I.; Bonnin, V.; Fistakoris, M.; Anifantakis, E.; Jaubert, G.; et al. Characteristics of Goat Milk Collected from Small and Medium Enterprises in Greece, Portugal and France. Small Ruminant Research 2003, 47, 39–49. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, H.K.; Fiechter, G. Physical and Chemical Characteristics of Sheep and Goat Milk in Austria. International Dairy Journal 2012, 24, 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Akbulut Çakır, Ç.; Teker, E. A Comparison of the Acid Gelation Properties of Nonfat Cow, Sheep, and Goat Milk with Standardized Protein Contents. Food Processing Preservation 2022, 46. [CrossRef]

- Fox, P.F.; Uniacke-Lowe, T.; McSweeney, P.L.H.; O’Mahony, J.A. Physical Properties of Milk. In Dairy Chemistry and Biochemistry; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-14891-5.

- Díaz, J.R.; Romero, G.; Muelas, R.; Alejandro, M.; Peris, C. Effect of Intramammary Infection on Milk Electrical Conductivity in Murciano-Granadina Goats. Journal of Dairy Science 2012, 95, 718–726. [CrossRef]

- Paterna, A.; Contreras, A.; Gómez-Martín, A.; Amores, J.; Tatay-Dualde, J.; Prats-van Der Ham, M.; Corrales, J.C.; Sánchez, A.; De La Fe, C. The Diagnosis of Mastitis and Contagious Agalactia in Dairy Goats. Small Ruminant Research 2014, 121, 36–41. [CrossRef]

- Kasapidou, E.; Basdagianni, Z.; Papadopoulos, V.; Karaiskou, C.; Kesidis, A.; Tsiotsias, A. Effects of Intensive and Semi-Intensive Production on Sheep Milk Chemical Composition, Physicochemical Characteristics, Fatty Acid Profile, and Nutritional Indices. Animals 2021, 11, 2578. [CrossRef]

- Smistad, M.; Inglingstad, R.A.; Skeie, S. Seasonal Dynamics of Bulk Milk Somatic Cell Count in Grazing Norwegian Dairy Goats. JDS Communications 2024, 5, 205–209. [CrossRef]

- Desidera, F.; Skeie, S.B.; Devold, T.G.; Inglingstad, R.A.; Porcellato, D. Fluctuations in Somatic Cell Count and Their Impact on Individual Goat Milk Quality throughout Lactation. Journal of Dairy Science 2025, 108, 152–163. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Granado, R.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, M.; Arce, C.; Rodríguez-Estévez, V. Factors Affecting Somatic Cell Count in Dairy Goats: A Review. Span. j. agric. res. 2014, 12, 133–150. [CrossRef]

- Lianou, D.T.; Michael, C.K.; Vasileiou, N.G.C.; Liagka, D.V.; Mavrogianni, V.S.; Caroprese, M.; Fthenakis, G.C. Association of Breed of Sheep or Goats with Somatic Cell Counts and Total Bacterial Counts of Bulk-Tank Milk. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 7356. [CrossRef]

- Paschino, P.; Stocco, G.; Dettori, M.L.; Pazzola, M.; Marongiu, M.L.; Pilo, C.E.; Cipolat-Gotet, C.; Vacca, G.M. Characterization of Milk Composition, Coagulation Properties, and Cheese-Making Ability of Goats Reared in Extensive Farms. Journal of Dairy Science 2020, 103, 5830–5843. [CrossRef]

- Idamokoro, E.; Muchenje, V.; Masika, P. Yield and Milk Composition at Different Stages of Lactation from a Small Herd of Nguni, Boer, and Non-Descript Goats Raised in an Extensive Production System. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1000. [CrossRef]

- Manousidis, T.; Parissi, Z.M.; Kyriazopoulos, A.P.; Malesios, C.; Koutroubas, S.D.; Abas, Z. Relationships among Nutritive Value of Selected Forages, Diet Composition and Milk Quality in Goats Grazing in a Mediterranean Woody Rangeland. Livestock Science 2018, 218, 8–19. [CrossRef]

- Olechnowicz, J.; Sobek, Z. Factors of Variation Influencing Production Level,SCC and Basic Milk Composition in Dairy Goats. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2008, 17, 41–49. [CrossRef]

- Noutfia, Y.; Zantar, S.; Ibnelbachyr, M.; Abdelouahab, S.; Ounas, I. Effect of Stage of Lactation on the Physical and Chemical Composition of Drâa Goat Milk. AJFAND 2014, 14, 9181–9191. [CrossRef]

- Ibnelbachyr, M.; Boujenane, I.; Chikhi, A.; Noutfia, Y. Effect of Some Non-Genetic Factors on Milk Yield and Composition of Draa Indigenous Goats under an Intensive System of Three Kiddings in 2 Years. Trop Anim Health Prod 2015, 47, 727–733. [CrossRef]

- Kondyli, E.; Katsiari, M.C.; Voutsinas, L.P. Variations of Vitamin and Mineral Contents in Raw Goat Milk of the Indigenous Greek Breed during Lactation. Food Chemistry 2007, 100, 226–230. [CrossRef]

- Currò, S.; De Marchi, M.; Claps, S.; Salzano, A.; De Palo, P.; Manuelian, C.; Neglia, G. Differences in the Detailed Milk Mineral Composition of Italian Local and Saanen Goat Breeds. Animals 2019, 9, 412. [CrossRef]

- Stergiadis, S.; Nørskov, N.P.; Purup, S.; Givens, I.; Lee, M.R.F. Comparative Nutrient Profiling of Retail Goat and Cow Milk. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2282. [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Yu, Z.; Jiang, H.; Shi, C.; Du, Q.; Fan, R.; Wang, J.; Bari, L.; Yang, Y.; Han, R. Effect of Lactation on the Distribution of Mineral Elements in Goat Milk. Journal of Dairy Science 2024, 107, 2774–2784. [CrossRef]

- Mestawet, T.A.; Girma, A.; Ådnøy, T.; Devold, T.G.; Narvhus, J.A.; Vegarud, G.E. Milk Production, Composition and Variation at Different Lactation Stages of Four Goat Breeds in Ethiopia. Small Ruminant Research 2012, 105, 176–181. [CrossRef]

| Farming System | Year | Lactation Stage | Significance | ||||||||||||

| Variable | E1 n=919 |

I2 n=909 |

SED3FS | 2022 n=938 |

2023 n=890 |

SED3Y | 1stn=458 | 2ndn=472 | 3rdn=450 | 4thn=448 | SED3LS | FS | Y | LS | YxLS |

| am_MY (kg) | 0.85a | 0.98b | 0.015 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.012 | 1.05a | 0.96b | 1.01a | 0.67c | 0.017 | ** | NS | *** | *** |

| Fat (%) | 4.76 | 4.75 | 0.034 | 4.72 | 4.75 | 0.033 | 4.69a | 4.83b | 4.74a | 4.78a | 0.048 | NS | NS | * | ** |

| Protein (%) | 3.57a | 3.47b | 0.012 | 3.59a | 3.45b | 0.011 | 3.58a | 3.57a | 3.43b | 3.51c | 0.017 | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Lactose (%) | 4.58 | 4.57 | 0.009 | 4.63a | 4.52b | 0.008 | 4.74a | 4.62b | 4.54c | 4.42d | 0.013 | NS | ** | *** | *** |

| TS (%) | 12.95 | 12.88 | 0.034 | 13.04a | 12.83b | 0.033 | 13.09a | 13.09a | 12.77b | 12.71b | 0.046 | NS | *** | *** | *** |

| Cas (%) | 2.72a | 2.57b | 0.009 | 2.66a | 2.63b | 0.008 | 2.71a | 2.68a | 2.58b | 2.62b | 0.012 | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Year | 2022 | 2023 | |||||||||||

| Lactation Stage | 1stn=458 | 2ndn=472 | 3rdn=450 | 4thn=448 | SED1 | Sig | 1stn=458 | 2ndn=472 | 3rdn=450 | 4thn=448 | SED1 | Sig | |

| Extensive | |||||||||||||

| am_MY (kg) | 1.09ab | 1.04b | 0.99ab | 0.34d | 0.03 | *** | 0.99a | 0.95a | 0.84b | 0.61c | 0.03 | *** | |

| Fat (%) | 4.78ab | 4.77ab | 4.62a | 4.94b | 0.05 | *** | 4.74ab | 4.88a | 4.64bc | 4.44c | 0.05 | *** | |

| Protein (%) | 3.75a | 3.64b | 3.42c | 3.56d | 0.02 | *** | 3.63a | 3.70a | 3.47b | 3.36c | 0.02 | *** | |

| Lactose (%) | 4.68a | 4.68a | 4.64a | 4.42b | 0.02 | *** | 4.77a | 4.59b | 4.49c | 4.37d | 0.02 | *** | |

| TS (%) | 13.29a | 13.18a | 12.77b | 12.99b | 0.08 | *** | 13.22a | 13.24a | 12.69b | 12.25c | 0.08 | *** | |

| Cas (%) | 2.97a | 2.87b | 2.67c | 2.66c | 0.02 | *** | 2.83a | 2.65b | 2.61b | 2.52c | 0.02 | *** | |

| Intensive | |||||||||||||

| am_MY (kg) | 1.16a | 0.87b | 1.05c | 0.80b | 0.03 | *** | 0.98a | 0.98a | 1.16b | 0.89a | 0.03 | *** | |

| Fat (%) | 4.22a | 4.71b | 4.86b | 4.88b | 0.05 | *** | 5.01a | 4.94abc | 4.78cd | 4.56d | 0.05 | *** | |

| Protein (%) | 3.71a | 3.54b | 3.49b | 3.68a | 0.02 | *** | 3.24a | 3.40b | 3.33c | 3.42b | 0.02 | *** | |

| Lactose (%) | 4.78a | 4.76a | 4.58b | 4.53b | 0.02 | *** | 4.72a | 4.45b | 4.43b | 4.36c | 0.02 | *** | |

| TS (%) | 12.79a | 13.08b | 13.00ab | 13.17b | 0.08 | *** | 13.06a | 12.88a | 12.61b | 12.42b | 0.08 | *** | |

| Cas (%) | 2.50ab | 2.53b | 2.48ac | 2.61d | 0.02 | *** | 2.53a | 2.65bd | 2.59ab | 2.67cd | 0.02 | *** | |

| Farming System | Year | Lactation Stage | Significance | ||||||||||||

| Variable | E1 n=919 |

I2 n=909 |

SED3FS | 2022 n=938 |

2023 n=890 |

SED3Y | 1st n=458 |

2nd n=472 |

3rd n=450 |

4th n=448 |

SED3LS | FS | Y | LS | Y*LS |

| pH | 6.67 | 6.68 | 0.004 | 6.68 | 6.67 | 0.005 | 6.65a | 6.66a | 6.65a | 6.75b | 0.007 | NS | NS | *** | NS |

| EC (mS/cm) | 5.77a | 5.74b | 0.020 | 5.77 | 5.74 | 0.020 | 5.73a | 5.70a | 5.88b | 5.72a | 0.037 | *** | NS | * | NS |

| RI | 1.348 | 1.349 | 0.001 | 1.349 | 1.348 | 0.001 | 1.349a | 1.349a | 1.348a | 1.347b | 0.001 | NS | NS | *** | NS |

| Brix (°Bx) | 10.51a | 10.11b | 0.043 | 10.51 | 10.26 | 0.003 | 10.72a | 10.44b | 10.23c | 9.86d | 0.061 | ** | NS | *** | NS |

| log10 SCC/ml | 5.687a | 5.504b | 0.024 | 5.487a | 5.705b | 0.020 | 5.529a | 5.439b | 5.623c | 5.792d | 0.028 | *** | * | *** | NS |

| log10 TBC ((cfu/ml) | 1.592a | 1.285b | 0.032 | 1.450 | 1.448 | 0.026 | 1.704a | 1.238b | 1.391c | 1.449c | 0.037 | *** | NS | *** | NS |

| Farming System | Year | Lactation Stage | Significance | ||||||||||

| Variable | E1 n=100 |

I2 n=100 |

SED3FS | 2022 n=100 |

2023 n=100 |

SED3Y | 1st n=100 |

3rd n=100 |

SED3LS | FS | Y | LS | Y*LS |

| Ca mg/Kg | 1246,72 | 1274,76 | 15.37 | 1260.83 | 1260.65 | 15.31 | 1295,17a | 1226,31b | 15.30 | NS | NS | *** | *** |

| Mg mg/Kg | 149,80a | 143,57b | 2.40 | 146,72 | 146,65 | 2.40 | 141,86a | 151,51b | 2.40 | *** | NS | *** | *** |

| Fe mg/Kg | 0.42a | 0.36b | 0.023 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.024 | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.023 | *** | NS | NS | *** |

| Zn mg/Kg | 3.74 | 3.71 | 0.082 | 3.73 | 3.72 | 0.082 | 3.81 | 3.65 | 0.081 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| P mg/Kg | 988.07 | 984.80 | 16.50 | 986.412 | 986.47 | 16.50 | 949.11a | 1023.77b | 16.51 | *** | NS | ** | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).