Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

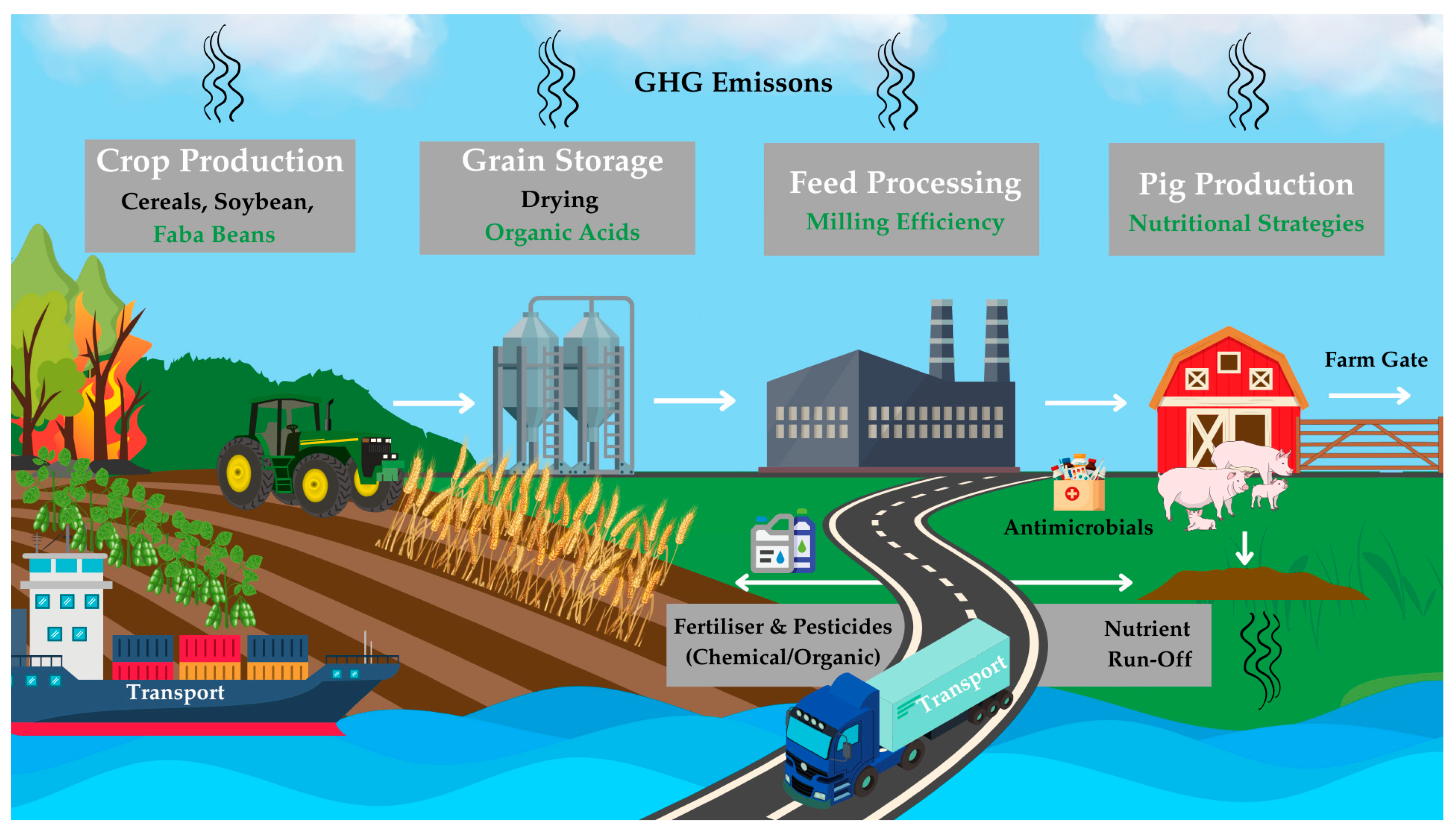

1. Introduction

2. Life Cycle Assessment in Pig Production

2.1. Methodology

2.2. Limitaions and Opportunities

2.3. Production Hotspots

3. Nutritional Strategies for Enhancing Sustainability of Pig Production

3.1. Feed Formulation and Ingredient Sourcing

3.2. Nutritional Interventions for Minimising Nutrient Losses, Manure Emissions, and Odour

3.3. Integrating Faba Beans into Pig Diets: Opportunities and Challeneges

3.4. Importance of Grain Preservation for Feed Sustainability

3.5. The Potential of Organic Acids as Grain Preservatives in Sustainable Pig Production

3.6. The Potential of Organic Acids as Functional Feed Additives in Sustainable Pig Nutrition

3.7. The Role of Organic Acids in Weaner and Grower-Finisher Diets

3.8. The Role of Organic Acids in Sow Diets

| Supplementation Period |

Organic Acid and Inclusion Level |

Parity | Lactation Length | Main Effects on Sow | Main Effects on Offspring | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 days (d90 of gestation) |

Citric acid (0.5, 1.0, or 1.5%) |

3.8 | 24 days |

|

|

[263] |

| 41 days (d95 of gestation) |

Fumaric, citric, malic, caprylic, and capric acid blend (0.1 and 0.2%) | 4.0 | 21 days |

|

|

[264] |

| 70 days (d73 of gestation) |

Fumaric, citric, malic, caprylic and capric acid blend (0.1 and 0.2%) | 3.3 | 28 days |

|

|

[265] |

| 51 days (d85 of gestation) |

Formic, propionic, butyric acid and ammonium salt blend (0.25%) | 4.4 | 21 days |

|

|

[267] |

| 29 days (d107 of gestation) |

Formic, acetic, lactic, citric, propionic, sorbic, caprylic, capric and lauric acid blend (0.1 and 0.3%) |

2.6 | 21 days |

|

|

[268] |

| 52 days (d85 of gestation) |

Sodium butyrate (0.1%) | 3.0 | 22 days |

|

|

[271] |

| 35 days (d100 of gestation) |

Butyric (Tributyrin 0.05%) |

N/A | 21 days |

|

|

[278] |

| N/A Entire cycle |

K-diformate and formic acid (0.8 and 1.2%) | 3.4 | 28 days |

|

|

[279] |

| 32 days (d108 of gestation) |

Citric and sorbic acid blend (0.05 or 0.1%) | 1.5 | 25 days |

|

|

[280] |

| N/A Late gestation |

Sodium butyrate (0.05% or 0.1%) |

3.6 | N/A |

|

|

[281] |

| 26 days (d110 of gestation) |

Sorbic, formic, acetic, lactic, propionic and MCFA blend (0.3%) |

4.8 | 21 days |

|

|

[282] |

| 40 days (d100 of gestation) |

Organic acid-preserved grain (65% propionic acid blend) | 3.2 | 26 days |

|

|

[283] |

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Dijk, M.; Morley, T.; Rau, M.L.; Saghai, Y. A Meta-Analysis of Projected Global Food Demand and Population at Risk of Hunger for the Period 2010–2050. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcon, W.P.; Naylor, R.L.; Shankar, N.D. Rethinking Global Food Demand for 2050. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2022, 48, 921–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, B.; Sharma, P. A Review of Literature on Climate Change and Its Impacts on Agriculture Productivity. J. Public Aff. 2019, 19, e1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneralp, B.; Reba, M.; Hales, B.U.; Wentz, E.A.; Seto, K.C. Trends in Urban Land Expansion, Density, and Land Transitions from 1970 to 2010: A Global Synthesis. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 044015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, M.; de Boer, I.J.M. Comparing Environmental Impacts for Livestock Products: A Review of Life Cycle Assessments. Livest. Sci. 2010, 128, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crop Production and Global Environmental Issues; Hakeem, K. R., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-23161-7. [Google Scholar]

- FAO Meat Market Review: Emerging Trends and Outlook in 2024; Rome, Italy, 2024.

- Pereira, P.M.D.C.C.; Vicente, A.F.D.R.B. Meat Nutritional Composition and Nutritive Role in the Human Diet. Meat Sci. 2013, 93, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.S.; Imran, A.; Hussain, M.B. Nutritional Composition of Meat. In Meat Science and Nutrition; Arshad, M.S., Ed.; InTech, 2018 ISBN 978-1-78984-233-3.

- Dutt, T. Commercial Pig Farming Scenario, Challenges, and Prospects. In Commercial Pig Farming; Elsevier, 2025; pp. 1–14 ISBN 978-0-443-23769-0.

- Diana, A.; Snijders, S.; Rieple, A.; Boyle, L.A. Why Do Irish Pig Farmers Use Medications? Barriers for Effective Reduction of Antimicrobials in Irish Pig Production. Ir. Vet. J. 2021, 74, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, H.; Balmford, A.; Wood, J.L.N.; Holmes, M.A. Identifying Ways of Producing Pigs More Sustainably: Tradeoffs and Co-Benefits in Land and Antimicrobial Use. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pexas, G.; Kyriazakis, I. Hotspots and Bottlenecks for the Enhancement of the Environmental Sustainability of Pig Systems, with Emphasis on European Pig Systems. Porc. Health Manag. 2023, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.-J.; Humphreys, J.; Holden, N.M. Evaluation of Process and Input–Output-Based Life-Cycle Assessment of Irish Milk Production. J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 151, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herron, J.; Curran, T.P.; Moloney, A.P.; McGee, M.; O’Riordan, E.G.; O’Brien, D. Life Cycle Assessment of Pasture-Based Suckler Steer Weanling-to-Beef Production Systems: Effect of Breed and Slaughter Age. Animal 2021, 15, 100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, D.; Lanigan, G.; Tresise, M.; Wynn, S.; Kealy, J.; Ryan, P.; Spink, J. A Life Cycle Assessment Model of Irish Grain Cropping Systems Focused on Carbon Footprint. Ir. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinee, J.B. Handbook on Life Cycle Assessment Operational Guide to the ISO Standards. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2002, 7, 311, BF02978897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gislason, S.; Birkved, M.; Maresca, A. A Systematic Literature Review of Life Cycle Assessments on Primary Pig Production: Impacts, Comparisons, and Mitigation Areas. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 42, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuliffe, G.A.; Chapman, D.V.; Sage, C.L. A Thematic Review of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Applied to Pig Production. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2016, 56, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andretta, I.; Hickmann, F.M.W.; Remus, A.; Franceschi, C.H.; Mariani, A.B.; Orso, C.; Kipper, M.; Létourneau-Montminy, M.-P.; Pomar, C. Environmental Impacts of Pig and Poultry Production: Insights From a Systematic Review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 750733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkar, H.P.S.; Ankers, P. Towards Sustainable Animal Diets: A Survey-Based Study. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2014, 198, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Quelen, F.; Brossard, L.; Wilfart, A.; Dourmad, J.-Y.; Garcia-Launay, F. Eco-Friendly Feed Formulation and On-Farm Feed Production as Ways to Reduce the Environmental Impacts of Pig Production Without Consequences on Animal Performance. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 689012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollnow, F.; Hissa, L.D.B.V.; Rufin, P.; Lakes, T. Property-Level Direct and Indirect Deforestation for Soybean Production in the Amazon Region of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pexas, G.; Doherty, B.; Kyriazakis, I. The Future of Protein Sources in Livestock Feeds: Implications for Sustainability and Food Safety. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1188467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestingi, A. Alternative and Sustainable Protein Sources in Pig Diet: A Review. Animals 2024, 14, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jezierny, D.; Mosenthin, R.; Bauer, E. The Use of Grain Legumes as a Protein Source in Pig Nutrition: A Review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2010, 157, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, K.J.; Dahal, P.; Van Asbrouck, J.; Kunusoth, K.; Bello, P.; Thompson, J.; Wu, F. The Dry Chain: Reducing Postharvest Losses and Improving Food Safety in Humid Climates. In Food Industry Wastes; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 375–389 ISBN 978-0-12-817121-9.

- Wang, X.; Dou, Z.; Feng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Zou, C.; Bai, Z.; Lakshmanan, P.; Shi, X.; Liu, D.; et al. Global Food Nutrients Analysis Reveals Alarming Gaps and Daunting Challenges. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolawole, O.; Siri-Anusornsak, W.; Petchkongkaew, A.; Elliott, C. A Systematic Review of Global Occurrence of Emerging Mycotoxins in Crops and Animal Feeds, and Their Toxicity in Livestock. Emerg. Contam. 2024, 10, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Farhad, Md.; Aonti, A.J.; Kabir, P.; Hossain, M.; Ahmed, B.; Haq, I.; Azim, J. Cereals Production under Changing Climate. In Challenges and Solutions of Climate Impact on Agriculture; Elsevier, 2025; pp. 63–83 ISBN 978-0-443-23707-2.

- Menon, A.; Stojceska, V.; Tassou, S.A. A Systematic Review on the Recent Advances of the Energy Efficiency Improvements in Non-Conventional Food Drying Technologies. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 100, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, K.; Mikula, K.; Izydorczyk, G.; Skrzypczak, D.; Witek-Krowiak, A.; Moustakas, K.; Ludwig, W.; Kułażyński, M. Improvements in Drying Technologies - Efficient Solutions for Cleaner Production with Higher Energy Efficiency and Reduced Emission. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Amer, A.; Elsebaee, I.; Sabahe, A.; Amer, M.A. Applied Insight: Studying Reducing the Carbon Footprint of the Drying Process and Its Environmental Impact and Financial Return. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1355133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, H.T.; Sarker, S.H. Comprehensive Energy Analysis and Environmental Sustainability of Industrial Grain Drying. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, H.L.; Li, P.; Zeng, Z.K.; Tian, Q.Y.; Piao, X.S.; Kuang, E.Y.W. A Comparison of the Nutritional Value of Organic-Acid Preserved Corn and Heat-Dried Corn for Pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2016, 214, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Pitarch, A.; Perez-Vendrell, A.M.; Manzanilla, E.G.; Gardiner, G.E.; Ryan, T.; O Doherty, J.V.; Torrallardona, D.; Lawlor, P.G. Effect of Raw and Extruded Propionic Acid-Treated Field Beans on Energy and Crude Protein Digestibility (In-Vitro and In-Vivo), Growth and Carcass Quality in Grow-Finisher Pigs. Animals 2021, 11, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konieczka, P.; Józefiak, D.; Kinsner, M.; Smulikowska, S. Effects of High-Moisture Corn Preserved with Organic Acids Combined with Rapeseed Meal and Peas on Performance and Gut Microbiota Activity of Broiler Chickens. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2021, 280, 115063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Long, W.; Chadwick, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Piao, X.; Hou, Y. Dietary Acidifiers as an Alternative to Antibiotics for Promoting Pig Growth Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2022, 289, 115320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suiryanrayna, M.V.A.N.; Ramana, J.V. A Review of the Effects of Dietary Organic Acids Fed to Swine. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugnoli, B.; Giovagnoni, G.; Piva, A.; Grilli, E. From Acidifiers to Intestinal Health Enhancers: How Organic Acids Can Improve Growth Efficiency of Pigs. Animals 2020, 10, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, M.E.E.; Smyth, S.; Beattie, V.E.; McCracken, K.J.; McCormack, U.; Muns, R.; Gordon, F.J.; Bradford, R.; Reid, L.A.; Magowan, E. The Environmental Impact of Lowering Dietary Crude Protein in Finishing Pig Diets—The Effect on Ammonia, Odour and Slurry Production. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Cho, S.B.; Kim, I.H. Strategies for Reducing Noxious Gas Emissions in Pig Production: A Comprehensive Review on the Role of Feed Additives. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2024, 66, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormley, A.; Jang, K.B.; Garavito-Duarte, Y.; Deng, Z.; Kim, S.W. Impacts of Maternal Nutrition on Sow Performance and Potential Positive Effects on Piglet Performance. Animals 2024, 14, 1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoiu, D.; Ionescu, G.H.; Cismaș, C.M.; Costin, M.P.; Cismaș, L.M.; Ciobanu, Ștefan C. F. Sustainable Production and Consumption in EU Member States: Achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 12). Sustainability 2025, 17, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabato, W.; Getnet, G.T.; Sinore, T.; Nemeth, A.; Molnár, Z. Towards Climate-Smart Agriculture: Strategies for Sustainable Agricultural Production, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Reduction. Agronomy 2025, 15, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinée, J. Handbook on Life Cycle Assessment — Operational Guide to the ISO Standards. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2001, 6, 255–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosnier, E.; Van Der Werf, H.M.G.; Boissy, J.; Dourmad, J.-Y. Evaluation of the Environmental Implications of the Incorporation of Feed-Use Amino Acids in the Manufacturing of Pig and Broiler Feeds Using Life Cycle Assessment. Animal 2011, 5, 1972–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reckmann, K.; Traulsen, I.; Krieter, J. Environmental Impact Assessment – Methodology with Special Emphasis on European Pork Production. J. Environ. Manage. 2012, 107, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dourmad, J.Y.; Ryschawy, J.; Trousson, T.; Bonneau, M.; Gonzàlez, J.; Houwers, H.W.J.; Hviid, M.; Zimmer, C.; Nguyen, T.L.T.; Morgensen, L. Evaluating Environmental Impacts of Contrasting Pig Farming Systems with Life Cycle Assessment. Animal 2014, 8, 2027–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAuliffe, G.A.; Takahashi, T.; Mogensen, L.; Hermansen, J.E.; Sage, C.L.; Chapman, D.V.; Lee, M.R.F. Environmental Trade-Offs of Pig Production Systems under Varied Operational Efficiencies. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noya, I.; Villanueva-Rey, P.; González-García, S.; Fernandez, M.D.; Rodriguez, M.R.; Moreira, M.T. Life Cycle Assessment of Pig Production: A Case Study in Galicia. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 4327–4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Grinsven, H.J.M.; Van Eerdt, M.M.; Westhoek, H.; Kruitwagen, S. Benchmarking Eco-Efficiency and Footprints of Dutch Agriculture in European Context and Implications for Policies for Climate and Environment. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottosen, M.; Mackenzie, S.G.; Filipe, J.A.N.; Misiura, M.M.; Kyriazakis, I. Changes in the Environmental Impacts of Pig Production Systems in Great Britain over the Last 18 Years. Agric. Syst. 2021, 189, 103063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, M.C.; Keoleian, G.A.; Willett, W.C. Toward a Life Cycle-Based, Diet-Level Framework for Food Environmental Impact and Nutritional Quality Assessment: A Critical Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 12632–12647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonesson, U.; Davis, J.; Flysjö, A.; Gustavsson, J.; Witthöft, C. Protein Quality as Functional Unit – A Methodological Framework for Inclusion in Life Cycle Assessment of Food. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuliffe, G.A.; Takahashi, T.; Lee, M.R.F. Applications of Nutritional Functional Units in Commodity-Level Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Agri-Food Systems. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnveden, G.; Hauschild, M.Z.; Ekvall, T.; Guinée, J.; Heijungs, R.; Hellweg, S.; Koehler, A.; Pennington, D.; Suh, S. Recent Developments in Life Cycle Assessment. J. Environ. Manage. 2009, 91, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colomb, V.; Ait Amar, S.; Mens, C.B.; Gac, A.; Gaillard, G.; Koch, P.; Mousset, J.; Salou, T.; Tailleur, A.; Van Der Werf, H.M.G. AGRIBALYSE ®, the French LCI Database for Agricultural Products: High Quality Data for Producers and Environmental Labelling. OCL 2015, 22, D104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernet, G.; Bauer, C.; Steubing, B.; Reinhard, J.; Moreno-Ruiz, E.; Weidema, B. The Ecoinvent Database Version 3 (Part I): Overview and Methodology. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlinger, B.; Koukouna, E.; Broekema, R.; van Paassen, M.; Scholten, J. Agri-Footprint 3.0; Blonk Consultants: Gouda, Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Poultry and Pig Nutrition: Challenges of the 21st Century; Hendriks, W. H., Verstegen, M.W.A., Babinszky, L., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, 2019; ISBN 978-90-8686-884-1. [Google Scholar]

- Starostka-Patyk, M. New Products Design Decision Making Support by SimaPro Software on the Base of Defective Products Management. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 65, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu, R.; Ab Aziz, M.A.; Che Hassan, C.H.; Noor, Z.Z.; Abd Jalil, R. Life Cycle Assessment Analyzing with Gabi Software for Food Waste Management Using Windrow and Hybrid Composting Technologies. J. Teknol. 2021, 83, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamu, Y.; Kumar, V.S.S.; Shakir, M.A.; Ubbana, H. Life Cycle Assessment of a Building Using Open-LCA Software. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 52, 1968–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brentrup, F.; Küsters, J.; Kuhlmann, H.; Lammel, J. Environmental Impact Assessment of Agricultural Production Systems Using the Life Cycle Assessment Methodology. Eur. J. Agron. 2004, 20, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebreab, E.; Liedke, A.; Caro, D.; Deimling, S.; Binder, M.; Finkbeiner, M. Environmental Impact of Using Specialty Feed Ingredients in Swine and Poultry Production: A Life Cycle Assessment1. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 2664–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, J.H.; Griffiths, A.; McNeill, R.; Halvorson, S.; Schenker, U.; Espinoza-Orias, N.; Morse, S.; Yang, A.; Sadhukhan, J. A Framework for Increasing the Availability of Life Cycle Inventory Data Based on the Role of Multinational Companies. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 1744–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brossard, L.; Van Milgen, J.; Dourmad, J.-Y.; Gaillard, C. Smart Pig Nutrition in the Digital Era. In Smart Livestock Nutrition; Kyriazakis, I., Ed.; Smart Animal Production; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; Vol. 1, pp. 169–199. ISBN 978-3-031-22583-3.

- Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing Food’s Environmental Impacts through Producers and Consumers. Science 2018, 360, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.V.; Andersen, H.M.-L.; Kristensen, T.; Schlægelberger, S.V.; Udesen, F.; Christensen, T.; Sandøe, P. Multidimensional Sustainability Assessment of Pig Production Systems at Herd Level – The Case of Denmark. Livest. Sci. 2023, 270, 105208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savian, M.; Da Penha Simon, C.; Holden, N.M. Evaluating Environmental, Economic, and Social Aspects of an Intensive Pig Production Farm in the South of Brazil: A Case Study. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2023, 28, 1544–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, P.; Steinfield, H.; Henderson, B.; Mottet, A.; Opio, C.; Dijkman, J.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G. Tackling Climate Change through Livestock A Global Assessment of Emissions and Mitigation Opportunities; Food and agriculture organization oF the united nations: Rome, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mielcarek-Bocheńska, P.; Rzeźnik, W. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Agriculture in EU Countries—State and Perspectives. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zervas, G.; Tsiplakou, E. An Assessment of GHG Emissions from Small Ruminants in Comparison with GHG Emissions from Large Ruminants and Monogastric Livestock. Atmos. Environ. 2012, 49, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferket, P.R.; Van Heugten, E.; Van Kempen, T.A.T.G.; Angel, R. Nutritional Strategies to Reduce Environmental Emissions from Nonruminants. J. Anim. Sci. 2002, 80, E168–E182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andretta, I.; Hauschild, L.; Kipper, M.; Pires, P.G.S.; Pomar, C. Environmental Impacts of Precision Feeding Programs Applied in Pig Production. Animal 2018, 12, 1990–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.L.T.; Hermansen, J.E.; Mogensen, L. Fossil Energy and GHG Saving Potentials of Pig Farming in the EU. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 2561–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanheira, É.G.; Freire, F. Greenhouse Gas Assessment of Soybean Production: Implications of Land Use Change and Different Cultivation Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 54, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, K.; Mikula, K.; Izydorczyk, G.; Skrzypczak, D.; Witek-Krowiak, A.; Moustakas, K.; Ludwig, W.; Kułażyński, M. Improvements in Drying Technologies - Efficient Solutions for Cleaner Production with Higher Energy Efficiency and Reduced Emission. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pexas, G.; Mackenzie, S.G.; Wallace, M.; Kyriazakis, I. Environmental Impacts of Housing Conditions and Manure Management in European Pig Production Systems through a Life Cycle Perspective: A Case Study in Denmark. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 120005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadero, A.; Aubry, A.; Brun, F.; Dourmad, J.Y.; Salaün, Y.; Garcia-Launay, F. Global Sensitivity Analysis of a Pig Fattening Unit Model Simulating Technico-Economic Performance and Environmental Impacts. Agric. Syst. 2018, 165, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meda, B.; Belloir, P.; Nancy, A.; Wilfart, A. Improving Environmental Sustainability of Poultry Production Using Innovative Feeding Strategies. 22nd Eur. Symp. Poult. Nutr. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Niemi, J.K.; Sevón-Aimonen, M.-L.; Pietola, K.; Stalder, K.J. The Value of Precision Feeding Technologies for Grow–Finish Swine. Livest. Sci. 2010, 129, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, J.E. Review: Nutrient and Energy Supply in Monogastric Food Producing Animals with Reduced Environmental and Climatic Footprint and Improved Gut Health. animal 2023, 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautrou, M.; Cappelaere, L.; Létourneau Montminy, M.-P. Phosphorus and Nitrogen Nutrition in Swine Production. Anim. Front. 2022, 12, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, H.H.; Lagos, L.V.; Casas, G.A. Nutritional Value of Feed Ingredients of Plant Origin Fed to Pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2016, 218, 33–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igiebor, F.A.; Uwuigiaren, N.J. Influence of Soil Microplastic Contamination on Maize (Zea Mays) Development and Microbial Dynamics. Discov. Environ. 2024, 2, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrie, S.B.; Bertolo, R.F.; Sauer, W.C.; Ball, R.O. Effect of Common Antinutritive Factors and Fibrous Feedstuffs in Pig Diets on Amino Acid Digestibilities with Special Emphasis on Threonine1,2. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 86, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach Knudsen, K.E.; Nørskov, N.P.; Bolvig, A.K.; Hedemann, M.S.; Laerke, H.N. Dietary Fibers and Associated Phytochemicals in Cereals. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiarie, E.; Walsh, M.C.; Nyachoti, C.M. Performance, Digestive Function, and Mucosal Responses to Selected Feed Additives for Pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dersjant-Li, Y.; Awati, A.; Schulze, H.; Partridge, G. Phytase in Non-ruminant Animal Nutrition: A Critical Review on Phytase Activities in the Gastrointestinal Tract and Influencing Factors. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 878–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Symeou, V.; Leinonen, I.; Kyriazakis, I. Modelling Phosphorus Intake, Digestion, Retention and Excretion in Growing and Finishing Pigs: Model Description. Animal 2014, 8, 1612–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahashon, S.; Kilonzo-Nthenge, A. Soybean in Monogastric Nutrition: Modifications to Add Value and Disease Prevention Properties. In Soybean - Bio-Active Compounds; El-Shemy, H., Ed.; InTech, 2013 ISBN 978-953-51-0977-8.

- Semper-Pascual, A.; Decarre, J.; Baumann, M.; Busso, J.M.; Camino, M.; Gómez-Valencia, B.; Kuemmerle, T. Biodiversity Loss in Deforestation Frontiers: Linking Occupancy Modelling and Physiological Stress Indicators to Understand Local Extinctions. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 236, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomone, R.; Saija, G.; Mondello, G.; Giannetto, A.; Fasulo, S.; Savastano, D. Environmental Impact of Food Waste Bioconversion by Insects: Application of Life Cycle Assessment to Process Using Hermetia Illucens. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 890–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malila, Y.; Owolabi, I.O.; Chotanaphuti, T.; Sakdibhornssup, N.; Elliott, C.T.; Visessanguan, W.; Karoonuthaisiri, N.; Petchkongkaew, A. Current Challenges of Alternative Proteins as Future Foods. Npj Sci. Food 2024, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traynor, A.; Burns, D.T.; Wu, D.; Karoonuthaisiri, N.; Petchkongkaew, A.; Elliott, C.T. An Analysis of Emerging Food Safety and Fraud Risks of Novel Insect Proteins within Complex Supply Chains. Npj Sci. Food 2024, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabue, S.L.; Kerr, B.J.; Scoggin, K.D.; Andersen, D.; Van Weelden, M. Swine Diets Impact Manure Characteristics and Gas Emissions: Part I Protein Level. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonderohe, C.E.; Brizgys, L.A.; Richert, J.A.; Radcliffe, J.S. Swine Production: How Sustainable Is Sustainability? Anim. Front. 2022, 12, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarnink, A.J.A.; Verstegen, M.W.A. Nutrition, Key Factor to Reduce Environmental Load from Pig Production. Livest. Sci. 2007, 109, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.B.; O’Shea, C.J.; Sweeney, T.; Callan, J.J.; O’Doherty, J.V. Effect of Crude Protein Concentration and Sugar-Beet Pulp on Nutrient Digestibility, Nitrogen Excretion, Intestinal Fermentation and Manure Ammonia and Odour Emissions from Finisher Pigs. Animal 2008, 2, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, C.J.; Gahan, D.A.; Lynch, M.B.; Callan, J.J.; O’Doherty, J.V. Effect of β-Glucan Source and Exogenous Enzyme Supplementation on Intestinal Fermentation and Manure Odour and Ammonia Emissions from Finisher Boars. Livest. Sci. 2010, 134, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, D.; O’Mara, F.P.; O’Doherty, J.V. The Effect of Dietary Crude Protein Concentration on Growth Performance, Carcass Composition and Nitrogen Excretion in Entire Grower-Finisher Pigs. Irish Journal of Agricultural and Food Research 2004, 43, 227–236. [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon, G.; Quinn, A.J. Pig Manure: A Valuable Fertiliser; Second.; Teagasc: Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dourmad, J.Y.; Guingand, N.; Latimier, P.; Sève, B. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Consumption, Utilisation and Losses in Pig Production: France. Livest. Prod. Sci. 1999, 58, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.J.A. Amino Acid Nutrition of the Pig. In Recent advances in animal nutrition; Butterworths: London, 1978; pp. 71–95. [Google Scholar]

- Achieving Sustainable Production of Pig Meat; Wiseman, J., Ed.; 0 ed.; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing, 2018; Vol. 2; ISBN 978-1-78676-095-1.

- Monteiro, A.N.T.R.; Dourmad, J.-Y.; Pozza, P.C. Life Cycle Assessment as a Tool to Evaluate the Impact of Reducing Crude Protein in Pig Diets. Ciênc. Rural 2017, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, L.A.C.; Monteiro, A.N.T.R.; Sitanaka, N.Y.; Oliveira, P.C.; Castilha, L.D.; Paula, V.R.C.; Pozza, P.C. The Reduction of Crude Protein with the Supplementation of Amino Acids in the Diet Reduces the Environmental Impact of Growing Pigs Production Evaluated through Life Cycle Assessment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, H.L.; Hausinger, R.P. Microbial Ureases: Significance, Regulation, and Molecular Characterization. Microbiol. Rev. 1989, 53, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canh, T.T.; Aarnink, A.J.A.; Schutte, J.B.; Sutton, A.; Langhout, D.J.; Verstegen, M.W.A. Dietary Protein Affects Nitrogen Excretion and Ammonia Emission from Slurry of Growing–Finishing Pigs. Livest. Prod. Sci. 1998, 56, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.B.; Sweeney, T.; Callan, B. Flynn, J.J.; O’Doherty, J.V. The Effect of High and Low Dietary Crude Protein and Inulin Supplementation on Nutrient Digestibility, Nitrogen Excretion, Intestinal Microflora and Manure Ammonia Emissions from Finisher Pigs. Animal 2007, 1, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.N.T.R.; Bertol, T.M.; De Oliveira, P.A.V.; Dourmad, J.-Y.; Coldebella, A.; Kessler, A.M. The Impact of Feeding Growing-Finishing Pigs with Reduced Dietary Protein Levels on Performance, Carcass Traits, Meat Quality and Environmental Impacts. Livest. Sci. 2017, 198, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabue, S.L.; Kerr, B.J.; Scoggin, K.D.; Andersen, D.; Van Weelden, M. Swine Diets Impact Manure Characteristics and Gas Emissions: Part II Protein Source. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 763, 144207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Dinh, P.; Van Der Peet-Schwering, C.; Ogink, N.; Aarnink, A. Effect of Diet Composition on Excreta Composition and Ammonia Emissions from Growing-Finishing Pigs. Animals 2022, 12, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Hu, L.; Liu, Y.; Yan, C.; Fang, Z.F.; Lin, Y.; Xu, S.Y.; Li, J.; Wu, C.M.; Chen, D.W.; et al. Effects of Low-Protein Diets Supplemented with Indispensable Amino Acids on Growth Performance, Intestinal Morphology and Immunological Parameters in 13 to 35 Kg Pigs. animal 2016, 10, 1812–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rattigan, R.; Sweeney, T.; Maher, S.; Ryan, M.T.; Thornton, K.; O’Doherty, J.V. Effects of Reducing Dietary Crude Protein Concentration and Supplementation with Either Laminarin or Zinc Oxide on the Growth Performance and Intestinal Health of Newly Weaned Pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 270, 114693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, P.D.; Aarnink, A.J.A.; Jongbloed, A.W. Odour and Ammonia Emission from Pig Manure as Affected by Dietary Crude Protein Level. Livest. Sci. 2009, 121, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, H.V.; Canibe, N.; Finster, K.; Jensen, B.B. Concentration of Volatile Sulphur-Containing Compounds along the Gastrointestinal Tract of Pigs Fed a High-Sulphur or a Low-Sulphur Diet. Livest. Sci. 2010, 133, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, J.M.; Callan, J.J.; O’Doherty, J.V. The Effect of Dietary Crude Protein Level, Cereal Type and Exogenous Enzyme Supplementation on Nutrient Digestibility, Nitrogen Excretion, Faecal Volatile Fatty Acid Concentration and Ammonia Emissions from Pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2006, 127, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.P.; O’Doherty, J.V.; Boland, T.M.; O’Shea, C.J.; Callan, J.J.; Pierce, K.M.; Lynch, M.B. The Effect of Benzoic Acid Concentration on Nitrogen Metabolism, Manure Ammonia and Odour Emissions in Finishing Pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2011, 163, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garry, B.P.; Fogarty, M.; Curran, T.P.; O’Connell, M.J.; O’Doherty, J.V. The Effect of Cereal Type and Enzyme Addition on Pig Performance, Intestinal Microflora, and Ammonia and Odour Emissions. Animal 2007, 1, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.B.; Sweeney, T.; Callan, J.J.; O’Doherty, J.V. Effects of Increasing the Intake of Dietary β-Glucans by Exchanging Wheat for Barley on Nutrient Digestibility, Nitrogen Excretion, Intestinal Microflora, Volatile Fatty Acid Concentration and Manure Ammonia Emissions in Finishing Pigs. Animal 2007, 1, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, C.J.; Sweeney, T.; Lynch, M.B.; Gahan, D.A.; Callan, J.J.; O’Doherty, J.V. Effect of -Glucans Contained in Barley- and Oat-Based Diets and Exogenous Enzyme Supplementation on Gastrointestinal Fermentation of Finisher Pigs and Subsequent Manure Odor and Ammonia Emissions. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, 1411–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, R.; Leterme, P. Feed Ingredients Differing in Fermentable Fibre and Indigestible Protein Content Affect Fermentation Metabolites and Faecal Nitrogen Excretion in Growing Pigs. Animal 2012, 6, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilfart, A.; Montagne, L.; Simmins, P.H.; Van Milgen, J.; Noblet, J. Sites of Nutrient Digestion in Growing Pigs: Effect of Dietary Fiber. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guggenbuhl, P.; Waché, Y.; Wilson, J.W. Effects of Dietary Supplementation with a Protease on the Apparent Ileal Digestibility of the Weaned Piglet. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 152–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Alpine, P.O.; O’Shea, C.J.; Varley, P.F.; Solan, P.; Curran, T.; O’Doherty, J.V. The Effect of Protease and Nonstarch Polysaccharide Enzymes on Manure Odor and Ammonia Emissions from Finisher Pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 369–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, C.J.; Mc Alpine, P.O.; Solan, P.; Curran, T.; Varley, P.F.; Walsh, A.M.; Doherty, J.V.O. The Effect of Protease and Xylanase Enzymes on Growth Performance, Nutrient Digestibility, and Manure Odour in Grower–Finisher Pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2014, 189, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Pitarch, A.; Manzanilla, E.G.; Gardiner, G.E.; O’Doherty, J.V.; Lawlor, P.G. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Feed Enzymes on Growth and Nutrient Digestibility in Grow-Finisher Pigs: Effect of Enzyme Type and Cereal Source. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2019, 251, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen, K.; Jalava, T.; Valaja, J.; Perttilä, S.; Siljander-Rasi, H.; Lindeberg, H. Effect of Dietary Carbadox or Formic Acid and Fibre Level on Ileal and Faecal Nutrient Digestibility and Microbial Metabolite Concentrations in Ileal Digesta of the Pig. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2001, 93, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagi, G.; Piva, A. In Vitro Effects of Some Organic Acids on Swine Cecal Microflora. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 6, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen, K.; Jalava, T.; Valaja, J. Effects of a Dietary Organic Acid Mixture and of Dietary Fibre Levels on Ileal and Faecal Nutrient Apparent Digestibility, Bacterial Nitrogen Flow, Microbial Metabolite Concentrations and Rate of Passage in the Digestive Tract of Pigs. Animal 2007, 1, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Jayaraman, B.; Kim, S.C.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, I.H.; Nyachoti, C.M. Effects of a Matrix-Coated Organic Acids and Medium-Chain Fatty Acids Blend on Performance, and in Vitro Fecal Noxious Gas Emissions in Growing Pigs Fed in-Feed Antibiotic-Free Diets. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 98, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, J.; Adamsen, A.P.S.; Nørgaard, J.V.; Poulsen, H.D.; Jensen, B.B.; Petersen, S.O. Emissions of Sulfur-Containing Odorants, Ammonia, and Methane from Pig Slurry: Effects of Dietary Methionine and Benzoic Acid. J. Environ. Qual. 2010, 39, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.B.; Song, Y.S.; Seo, S.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, B.G. Effects of Benzoic Acid in Pig Diets on Nitrogen Utilization, Urinary pH, Slurry pH, and Odorous Compounds. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 37, 2137–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Shea, C.J.; Sweeney, T.; Bahar, B.; Ryan, M.T.; Thornton, K.; O’Doherty, J.V. Indices of Gastrointestinal Fermentation and Manure Emissions of Growing-Finishing Pigs as Influenced through Singular or Combined Consumption of Lactobacillus Plantarum and Inulin. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 3848–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Shea, C.J.; Lynch, M.B.; Sweeney, T.; Gahan, D.A.; Callan, J.J.; O’Doherty, J.V. Comparison of a Wheat-Based Diet Supplemented with Purified β-Glucans, with an Oat-Based Diet on Nutrient Digestibility, Nitrogen Utilization, Distal Gastrointestinal Tract Composition, and Manure Odor and Ammonia Emissions from Finishing Pigs1. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, M.S.; Ijssennagger, N.; Kies, A.K.; Van Mil, S.W.C. Protein Fermentation in the Gut; Implications for Intestinal Dysfunction in Humans, Pigs, and Poultry. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2018, 315, G159–G170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrini, S.; Aquilani, C.; Pugliese, C.; Bozzi, R.; Sirtori, F. Soybean Replacement by Alternative Protein Sources in Pig Nutrition and Its Effect on Meat Quality. Animals 2023, 13, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD; FAO OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2024-2033; OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook; OECD, 2024; ISBN 978-92-64-72259-0.

- DAFM, D. Protein Aid Scheme; Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine, 2023.

- Prandini, A.; Sigolo, S.; Morlacchini, M.; Cerioli, C.; Masoero, F. Pea ( Pisum Sativum ) and Faba Bean ( Vicia Faba L. ) Seeds as Protein Sources in Growing-Finishing Heavy Pig Diets: Effect on Growth Performance, Carcass Characteristics and on Fresh and Seasoned Parma Ham Quality. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 10, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.A.; Houdijk, J.G.M.; Homer, D.; Kyriazakis, I. Effects of Dietary Inclusion of Pea and Faba Bean as a Replacement for Soybean Meal on Grower and Finisher Pig Performance and Carcass Quality1. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 3733–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, G.A.; Smith, L.A.; Houdijk, J.G.M.; Homer, D.; Kyriazakis, I.; Wiseman, J. Replacement of Soya Bean Meal with Peas and Faba Beans in Growing/Finishing Pig Diets: Effect on Performance, Carcass Composition and Nutrient Excretion. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2015, 209, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherif, C.; Hassanat, F.; Claveau, S.; Girard, J.; Gervais, R.; Benchaar, C. Faba Bean (Vicia Faba) Inclusion in Dairy Cow Diets: Effect on Nutrient Digestion, Rumen Fermentation, Nitrogen Utilization, Methane Production, and Milk Performance. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 8916–8928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahran, H.H. Rhizobium-Legume Symbiosis and Nitrogen Fixation under Severe Conditions and in an Arid Climate. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999, 63, 968–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neugschwandtner, R.; Ziegler, K.; Kriegner, S.; Wagentristl, H.; Kaul, H.-P. Nitrogen Yield and Nitrogen Fixation of Winter Faba Beans. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B — Soil Plant Sci. 2015, 65, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, J.P.; Teixeira, R.D.S.; Da Silva, I.R.; Soares, E.M.B.; Lima, A.M.N. Decomposition and Nutrient Release from Legume and Non-legume Residues in a Tropical Soil. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoussac, L.; Journet, E.-P.; Hauggaard-Nielsen, H.; Naudin, C.; Corre-Hellou, G.; Jensen, E.S.; Prieur, L.; Justes, E. Ecological Principles Underlying the Increase of Productivity Achieved by Cereal-Grain Legume Intercrops in Organic Farming. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 911–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocira, A.; Staniak, M.; Tomaszewska, M.; Kornas, R.; Cymerman, J.; Panasiewicz, K.; Lipińska, H. Legume Cover Crops as One of the Elements of Strategic Weed Management and Soil Quality Improvement. A Review. Agriculture 2020, 10, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahate, K.A.; Madhumita, M.; Prabhakar, P.K. Nutritional Composition, Anti-Nutritional Factors, Pretreatments-Cum-Processing Impact and Food Formulation Potential of Faba Bean (Vicia Faba L.): A Comprehensive Review. LWT 2021, 138, 110796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvant, D.; Perez, J.; Tran, G. Tables of Composition and Nutritional Value of Feed Materials: Pigs, Poultry, Cattle, Sheep, Goats, Rabbits, Horses and Fish; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Amstelveen, The Netherlands, 2004; ISBN 90-8686-668-9. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, H.H.; Sève, B.; Fuller, M.F.; Moughan, P.J.; De Lange, C.F.M. Invited Review: Amino Acid Bioavailability and Digestibility in Pig Feed Ingredients: Terminology and Application. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbas, B.; Machado, N.; Pathania, S.; Brites, C.; Rosa, E.A.; Barros, A.I. Potential of Legumes: Nutritional Value, Bioactive Properties, Innovative Food Products, and Application of Eco-Friendly Tools for Their Assessment. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 160–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusztai, A.; Bardocz, S. ; M A Martín-Cabrejas The Mode of Action of ANFs on the Gastrointestinal Tract and Its Microflora; Recent Advances of Research in Antinutritional Factors in Legume Seeds and Oilseeds; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, 2004; pp. 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer Labba, I.-C.; Frøkiær, H.; Sandberg, A.-S. Nutritional and Antinutritional Composition of Fava Bean (Vicia Faba L., Var. Minor) Cultivars. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 110038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerman, A.E.; Butler, L.G. Condensed Tannin Purification and Characterization of Tannin-Associated Proteins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1980, 28, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivarsson, E.; Neil, M. Variations in Nutritional and Antinutritional Contents among Faba Bean Cultivars and Effects on Growth Performance of Weaner Pigs. Livest. Sci. 2018, 212, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriquez, B.; Olson, M.A.; Hoy, C.F.; Jackson, M.; Wouda, T. Frost Tolerance of Faba Bean Cultivars (Vicia Faba L.) in Central Alberta. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2017; CJPS-2017-0078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houdijk, J.G.M.; Hartemink, R.; Verstegen, M.W.A.; Bosch, M. Effects of Dietary Non-Digestible Oligosaccharides on Microbial Characteristics of Ileal Chyme and Faeces in Weaner Pigs. Arch. Für Tierernaehrung 2002, 56, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, B.K. Drying and Storage of Cereal Grains; Second.; Wiley, 2016.

- Barrozo, M.A.S.; Mujumdar, A.; Freire, J.T. Air-Drying of Seeds: A Review. Dry. Technol. 2014, 32, 1127–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Los, A.; Ziuzina, D.; Bourke, P. Current and Future Technologies for Microbiological Decontamination of Cereal Grains: Decontamination Methods of Cereal Grains…. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 1484–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, V.; Paraginski, R.T.; Ferreira, C.D. Grain Storage Systems and Effects of Moisture, Temperature and Time on Grain Quality - A Review. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2021, 91, 101770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleurat-Lessard, F. STORED GRAIN | Physico-Chemical Treatment. In Encyclopedia of Grain Science; Elsevier, 2004; pp. 254–263 ISBN 978-0-12-765490-4.

- Jouany, J.P. Methods for Preventing, Decontaminating and Minimizing the Toxicity of Mycotoxins in Feeds. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2007, 137, 342–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimoh, K.A. Recent Advances in the Drying Process of Grains. Food Eng. Rev. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidhe, E. A Review of the Application of Modeling and Simulation to Drying Systems for Improved Grain and Seed Quality. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciorowski, K.G.; Herrera, P.; Jones, F.T.; Pillai, S.D.; Ricke, S.C. Effects on Poultry and Livestock of Feed Contamination with Bacteria and Fungi. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2007, 133, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryden, W.L. Mycotoxin Contamination of the Feed Supply Chain: Implications for Animal Productivity and Feed Security. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2012, 173, 134–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Song, G.; Lim, W. Effects of Mycotoxin-Contaminated Feed on Farm Animals. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 389, 122087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summers, K.L. Chapter 10 Mycotoxins and Swine Gut Health. In; Wageningen Academic: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 198–212. ISBN 978-90-04-69546-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pierron, A.; Alassane-Kpembi, I.; Oswald, I.P. Impact of Mycotoxin on Immune Response and Consequences for Pig Health. Anim. Nutr. 2016, 2, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneely, J.; Greer, B.; Kolawole, O.; Elliott, C. T-2 and HT-2 Toxins: Toxicity, Occurrence and Analysis: A Review. Toxins 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minervini, F.; Dell’Aquila, M.E. Zearalenone and Reproductive Function in Farm Animals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2008, 9, 2570–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denli, M.; Perez, J. Ochratoxins in Feed, a Risk for Animal and Human Health: Control Strategies. Toxins 2010, 2, 1065–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber-Dorninger, C.; Jenkins, T.; Schatzmayr, G. Global Mycotoxin Occurrence in Feed: A Ten-Year Survey. Toxins 2019, 11, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, Á.; González-Jartín, J.M.; Sainz, M.J. Impact of Global Warming on Mycotoxins. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2017, 18, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabak, B.; Dobson, A.D.W. Mycotoxins in Spices and Herbs–An Update. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manubolu, M.; Goodla, L.; Pathakoti, K.; Malmlöf, K. Enzymes as Direct Decontaminating Agents—Mycotoxins. In Enzymes in Human and Animal Nutrition; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 313–330 ISBN 978-0-12-805419-2.

- Ji, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, L. Review on Biological Degradation of Mycotoxins. Anim. Nutr. 2016, 2, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L.C.; Sweeney, T.; Curley, E.; Duffy, S.K.; Vigors, S.; Rajauria, G.; O’Doherty, J.V. Mycotoxin Binder Increases Growth Performance, Nutrient Digestibility and Digestive Health of Finisher Pigs Offered Wheat Based Diets Grown under Different Agronomical Conditions. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2018, 240, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolosova, A.; Stroka, J. Substances for Reduction of the Contamination of Feed by Mycotoxins: A Review. World Mycotoxin J. 2011, 4, 225–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, C.T.; Connolly, L.; Kolawole, O. Potential Adverse Effects on Animal Health and Performance Caused by the Addition of Mineral Adsorbents to Feeds to Reduce Mycotoxin Exposure. Mycotoxin Res. 2020, 36, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jokiniemi, H.T.; Ahokas, J.M. Drying Process Optimisation in a Mixed-Flow Batch Grain Dryer. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 121, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Adeola, O. Techniques for Evaluating Digestibility of Energy, Amino Acids, Phosphorus, and Calcium in Feed Ingredients for Pigs. Anim. Nutr. 2017, 3, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Chandel, S.S. Performance and Degradation Analysis for Long Term Reliability of Solar Photovoltaic Systems: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 27, 753–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL-Mesery, H.S.; EL-Seesy, A.I.; Hu, Z.; Li, Y. Recent Developments in Solar Drying Technology of Food and Agricultural Products: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 157, 112070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivkar, P.R.; Katekar, V.P.; Deshmukh, S.S.; Palatkar, S.V. Effect of Sensible Heat Storage Materials on the Thermal Performance of Solar Air Heaters: State-of-the-Art Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 157, 112085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, S.S.; Luthra, K.; Singh, C.B.; Atungulu, G.; Corscadden, K. On-Farm Grain Drying System Sustainability: Current Energy and Carbon Footprint Assessment with Potential Reform Measures. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 60, 103430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyuncu, S.; Andersson, M.G.; Löfström, C.; Skandamis, P.N.; Gounadaki, A.; Zentek, J.; Häggblom, P. Organic Acids for Control of Salmonella in Different Feed Materials. BMC Vet. Res. 2013, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijksterhuis, J.; Meijer, M.; Van Doorn, T.; Houbraken, J.; Bruinenberg, P. The Preservative Propionic Acid Differentially Affects Survival of Conidia and Germ Tubes of Feed Spoilage Fungi. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 306, 108258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Zannini, E.; Lynch, K.M.; Arendt, E.K. Novel Approaches for Chemical and Microbiological Shelf Life Extension of Cereal Crops. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 3395–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, S.; Sweeney, T.; Kiernan, D.P.; Ryan, M.T.; Gath, V.; Vigors, S.; Connolly, K.R.; O’Doherty, J.V. Organic Acid Preservation of Cereal Grains Improves Grain Quality, Growth Performance, and Intestinal Health of Post-Weaned Pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2024, 316, 116078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, K.R.; Sweeney, T.; Kiernan, D.P.; Round, A.; Ryan, M.T.; Gath, V.; Maher, S.; Vigors, S.; O’Doherty, J.V. The Role of Propionic Acid as a Feed Additive and Grain Preservative on Weanling Pig Performance and Digestive Health. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2025, 321, 116237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, K.R.; Sweeney, T.; Ryan, M.T.; Vigors, S.; O’Doherty, J.V. Impact of Reduced Dietary Crude Protein and Propionic Acid Preservation on Intestinal Health and Growth Performance in Post-Weaned Pigs. Animals 2025, 15, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, K.R.; Sweeney, T.; Ryan, M.T.; Vigors, S.; O’Doherty, J.V. Effects of Butyric Acid Supplementation on the Gut Microbiome and Growth Performance of Weanling Pigs Fed a Low-Crude Protein, Propionic Acid-Preserved Grain Diet. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, S.; Sweeney, T.; Vigors, S.; O’Doherty, J.V. Maternal and/or Direct Feeding of Organic Acid-Preserved Cereal Grains Improves Performance and Digestive Health of Pigs from Birth to Slaughter. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2025, 323, 116295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetti, A.; Tugnoli, B.; Piva, A.; Grilli, E. Towards Zero Zinc Oxide: Feeding Strategies to Manage Post-Weaning Diarrhea in Piglets. Animals 2021, 11, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadéro, A.; Aubry, A.; Dourmad, J.Y.; Salaün, Y.; Garcia-Launay, F. Effects of Interactions between Feeding Practices, Animal Health and Farm Infrastructure on Technical, Economic and Environmental Performances of a Pig-Fattening Unit. Animal 2020, 14, s348–s359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferronato, G.; Prandini, A. Dietary Supplementation of Inorganic, Organic, and Fatty Acids in Pig: A Review. Animals 2020, 10, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, B.V.; Muthuvel, S.; Govidasamy, P.; Villavan, M.; Alagawany, M.; Ragab Farag, M.; Dhama, K.; Gopi, M. Role of Acidifiers in Livestock Nutrition and Health: A Review. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 104, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, P.; Zaworska-Zakrzewska, A.; Frankiewicz, A.; Kasprowicz-Potocka, M. The Effects and Mechanisms of Acids on the Health of Piglets and Weaners – a Review. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2021, 21, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, D.; Mun, H.S.; Dilawar, M.A.; Baek, K.S.; Yang, C.J. Time for a Paradigm Shift in Animal Nutrition Metabolic Pathway: Dietary Inclusion of Organic Acids on the Production Parameters, Nutrient Digestibility, and Meat Quality Traits of Swine and Broilers. Life 2021, 11, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, Z.-X.; Tokach, M.D.; Woodworth, J.C.; DeRouchey, J.M.; Goodband, R.D.; Gebhardt, J.T. Effects of Various Feed Additives on Finishing Pig Growth Performance and Carcass Characteristics: A Review. Animals 2023, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, K.R.; Sweeney, T.; O’Doherty, J.V. Sustainable Nutritional Strategies for Gut Health in Weaned Pigs: The Role of Reduced Dietary Crude Protein, Organic Acids and Butyrate Production. Animals 2024, 15, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.B.; Diez-Gonzalez, F. The Effects of Fermentation Acids on Bacterial Growth. In Advances in Microbial Physiology; Elsevier, 1998; Vol. 39, pp. 205–234 ISBN 978-0-12-027739-1.

- Brul, S.; Coote, P. Preservative Agents in Foods Mode of Action and Microbial Resistance Mechanisms. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1999, 50, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’ Meara, F.M.; Gardiner, G.E.; O’ Doherty, J.V.; Lawlor, P.G. Effect of Dietary Inclusion of Benzoic Acid (VevoVitall®) on the Microbial Quality of Liquid Feed and the Growth and Carcass Quality of Grow-Finisher Pigs. Livest. Sci. 2020, 237, 104043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.Y.; Kil, D.Y.; Oh, H.K.; Han, I.K. Acidifier as an Alternative Material to Antibiotics in Animal Feed. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 18, 1048–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.M.; Opapeju, F.O.; Pluske, J.R.; Kim, J.C.; Hampson, D.J.; Nyachoti, C.M. Gastrointestinal Health and Function in Weaned Pigs: A Review of Feeding Strategies to Control Post-Weaning Diarrhoea without Using in-Feed Antimicrobial Compounds: Feeding Strategies without Using in-Feed Antibiotics. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2013, 97, 207–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, C.M.; Pettigrew, J.E. Critical Review of Acidifiers; National Pork Board: Des Moines, IA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Paulicks, B.R.; Roth, F.X.; Kirchgessner, M. Effects of Potassium Diformate (Formi® LHS) in Combination with Different Grains and Energy Densities in the Feed on Growth Performance of Weaned Piglets. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2000, 84, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Espinosa, C.D.; Abelilla, J.J.; Casas, G.A.; Lagos, L.V.; Lee, S.A.; Kwon, W.B.; Mathai, J.K.; Navarro, D.M.D.L.; Jaworski, N.W.; et al. Non-Antibiotic Feed Additives in Diets for Pigs: A Review. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 4, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecco, H.A.T.; Amorim, A.B.; Saleh, M.A.D.; Tse, M.L.P.; Telles, F.G.; Miassi, G.M.; Pimenta, G.M.; Berto, D.A. Evaluation of Growth Performance and Gastro-Intestinal Parameters on the Response of Weaned Piglets to Dietary Organic Acids. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2018, 90, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, C.F.; Riis, A.L.; Bresson, S.; Højbjerg, O.; Jensen, B.B. Feeding Organic Acids Enhances the Barrier Function against Pathogenic Bacteria of the Piglet Stomach. Livest. Sci. 2007, 108, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranwell, P.D.; Noakes, D.E.; Hill, K.J. Gastric Secretion and Fermentation in the Suckling Pig. Br. J. Nutr. 1976, 36, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawlor, P.G.; Lynch, P.B.; Caffrey, P.J.; O’Reilly, J.J.; O’Connell, M.K. Measurements of the Acid-Binding Capacity of Ingredients Used in Pig Diets. Ir. Vet. J. 2005, 58, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieper, R.; Villodre Tudela, C.; Taciak, M.; Bindelle, J.; Pérez, J.F.; Zentek, J. Health Relevance of Intestinal Protein Fermentation in Young Pigs. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2016, 17, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Y.; Che, L.; Xu, S.; Wu, D.; Xue, B.; et al. Effects of Dietary Combinations of Organic Acids and Medium Chain Fatty Acids as a Replacement of Zinc Oxide on Growth, Digestibility and Immunity of Weaned Pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2015, 208, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, J.W.; Hall, H.; Nyachoti, C.M. Effect of Dietary Organic Acids Supplementation on Growth Performance, Nutrient Digestibility, and Gut Morphology in Weaned Pigs. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 102, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walia, K.; Argüello, H.; Lynch, H.; Leonard, F.C.; Grant, J.; Yearsley, D.; Kelly, S.; Duffy, G.; Gardiner, G.E.; Lawlor, P.G. Effect of Strategic Administration of an Encapsulated Blend of Formic Acid, Citric Acid, and Essential Oils on Salmonella Carriage, Seroprevalence, and Growth of Finishing Pigs. Prev. Vet. Med. 2017, 137, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.H.; Seok, W.J.; Kim, I.H. Organic Acids Mixture as a Dietary Additive for Pigs—A Review. Animals 2020, 10, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiloyiannis, V.K.; Kyriakis, S.C.; Vlemmas, J.; Sarris, K. The Effect of Organic Acids on the Control of Porcine Post-Weaning Diarrhoea. Res. Vet. Sci. 2001, 70, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.J.; Park, J.W.; Baek, D.H.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, I.H. Feeding the Blend of Organic Acids and Medium Chain Fatty Acids Reduces the Diarrhea in Piglets Orally Challenged with Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli K88. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2017, 224, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluske, J.R.; Turpin, D.L.; Sahibzada, S.; Pineda, L.; Han, Y.; Collins, A. Impacts of Feeding Organic Acid-Based Feed Additives on Diarrhea, Performance, and Fecal Microbiome Characteristics of Pigs after Weaning Challenged with an Enterotoxigenic Strain of Escherichia Coli. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2021, 5, txab212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluske, J.R.; Hampson, D.J.; Williams, I.H. Factors Influencing the Structure and Function of the Small Intestine in the Weaned Pig: A Review. Livest. Prod. Sci. 1997, 51, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallès, J.-P.; Boudry, G.; Favier, C.; Le Floc’h, N.; Luron, I.; Montagne, L.; Oswald, I.P.; Pié, S.; Piel, C.; Sève, B. Gut Function and Dysfunction in Young Pigs: Physiology. Anim. Res. 2004, 53, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.-S.; J.-J.L.; X.-T.Z. Effects of Sodium Butyrate on the Intestinal Morphology and DNA-Binding Activity of Intestinal Nuclear Factor-κB in Weanling Pigs. J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2012, 11, 814–821. [CrossRef]

- Diao, H.; Gao, Z.; Yu, B.; Zheng, P.; He, J.; Yu, J.; Huang, Z.; Chen, D.; Mao, X. Effects of Benzoic Acid (VevoVitall®) on the Performance and Jejunal Digestive Physiology in Young Pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zheng, J.; Deng, K.; Chen, L.; Zhao, X.L.; Jiang, X.M.; Fang, Z.F.; Che, L.Q.; Xu, S.Y.; Feng, B.; et al. Supplementation with Organic Acids Showing Different Effects on Growth Performance, Gut Morphology and Microbiota of Weaned Pigs Fed with Highly or Less Digestible Diets. J. Anim. Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.F.; Xu, Y.T.; Pan, L.; Wang, Q.Q.; Wang, C.L.; Wu, J.Y.; Wu, Y.Y.; Han, Y.M.; Yun, C.H.; Piao, X.S. Mixed Organic Acids as Antibiotic Substitutes Improve Performance, Serum Immunity, Intestinal Morphology and Microbiota for Weaned Piglets. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2018, 235, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luise, D.; Motta, V.; Salvarani, C.; Chiappelli, M.; Fusco, L.; Bertocchi, M.; Mazzoni, M.; Maiorano, G.; Costa, L.N.; Van Milgen, J.; et al. Long-Term Administration of Formic Acid to Weaners: Influence on Intestinal Microbiota, Immunity Parameters and Growth Performance. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2017, 232, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wensley, M.R.; Tokach, M.D.; Woodworth, J.C.; Goodband, R.D.; Gebhardt, J.T.; DeRouchey, J.M.; McKilligan, D. Maintaining Continuity of Nutrient Intake after Weaning. II. Review of Post-Weaning Strategies. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2021, 5, txab022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholif, A.E.; Gouda, G.A.; Olafadehan, O.A.; Sallam, S.M.; Anele, U.Y. Acidifiers and Organic Acids in Livestock Nutrition and Health. In Organic Feed Additives for Livestock; Elsevier, 2025; pp. 43–56 ISBN 978-0-443-13510-1.

- Ottosen, M.; Mackenzie, S.G.; Wallace, M.; Kyriazakis, I. A Method to Estimate the Environmental Impacts from Genetic Change in Pig Production Systems. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosenthin, R.; Sauer, W.C.; Ahrens, F.; De Lange, C.F.M.; Bornholdt, U. Effect of Dietary Supplements of Propionic Acid, Siliceous Earth or a Combination of These on the Energy, Protein and Amino Acid Digestibilities and Concentrations of Microbial Metabolites in the Digestive Tract of Growing Pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1992, 37, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroz, Z.; Jongbloed, A.W.; Partanen, K.H.; Vreman, K.; Kemme, P.A.; Kogut, J. The Effects of Calcium Benzoate in Diets with or without Organic Acids on Dietary Buffering Capacity, Apparent Digestibility, Retention of Nutrients, and Manure Characteristics in Swine. J. Anim. Sci. 2000, 78, 2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhara, R.B.; Marume, U.; Nantapo, C.W.T. Potential of Organic Acids, Essential Oils and Their Blends in Pig Diets as Alternatives to Antibiotic Growth Promoters. Animals 2024, 14, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkosi, D.V.; Bekker, J.L.; Hoffman, L.C. The Use of Organic Acids (Lactic and Acetic) as a Microbial Decontaminant during the Slaughter of Meat Animal Species: A Review. Foods 2021, 10, 2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcenilla, C.; Ducic, M.; López, M.; Prieto, M.; Álvarez-Ordóñez, A. Application of Lactic Acid Bacteria for the Biopreservation of Meat Products: A Systematic Review. Meat Sci. 2022, 183, 108661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yi, G.; Yin, J.; Sun, P.; Li, D.; Knight, C. Effects of Organic Acids on Growth Performance, Gastrointestinal pH, Intestinal Microbial Populations and Immune Responses of Weaned Pigs. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 21, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.T.; Hwang, J.A.; Hoon, J.; Mun, H.S.; Yang, C.J. Comparison of Single and Blend Acidifiers as Alternative to Antibiotics on Growth Performance, Fecal Microflora, and Humoral Immunity in Weaned Piglets. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 27, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.S.; Tang, C.H.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Zhan, T.F.; Zhang, K.; Han, Y.M.; Zhang, J.M. Effects of Dietary Supplementation with Combinations of Organic and Medium Chain Fatty Acids as Replacements for Chlortetracycline on Growth Performance, Serum Immunity, and Fecal Microbiota of Weaned Piglets. Livest. Sci. 2018, 216, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zheng, J.; Deng, K.; Chen, L.; Zhao, X.L.; Jiang, X.M.; Fang, Z.F.; Che, L.Q.; Xu, S.Y.; Feng, B.; et al. Supplementation with Organic Acids Showing Different Effects on Growth Performance, Gut Morphology and Microbiota of Weaned Pigs Fed with Highly or Less Digestible Diets. J. Anim. Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, N.; Fariñas, F.; Cabrera-Gómez, C.G.; Pallares, F.J.; Ramis, G. Blend of Organic Acids Improves Gut Morphology and Affects Inflammation Response in Piglets after Weaning. Front. Anim. Sci. 2024, 5, 1308514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.T.; Liu, Li.; Long, S.F.; Pan, L.; Piao, X.S. Effect of Organic Acids and Essential Oils on Performance, Intestinal Health and Digestive Enzyme Activities of Weaned Pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2018, 235, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, I.H. Effects of Dietary Protected Organic Acids on Growth Performance, Nutrient Digestibility, Fecal Microflora, Diarrhea Score, and Fecal Gas Emission in Weanling Pigs. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 99, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.-D.; Deng, Z.-C.; Wang, Y.-W.; Sun, H.; Wang, L.; Han, Y.-M.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Liu, J.-G.; Sun, L.-H. Organic Acids Improve Growth Performance with Potential Regulation of Redox Homeostasis, Immunity, and Microflora in Intestines of Weaned Piglets. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhaya, S.D.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, I.H. Influence of Protected Organic Acid Blends and Diets with Different Nutrient Densities on Growth Performance, Nutrient Digestibility and Faecal Noxious Gas Emission in Growing Pigs. Veterinární Medicína 2014, 59, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhaya, S.D.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, I.H. Effect of Protected Organic Acid Blends on Growth Performance, Nutrient Digestibility and Faecal Micro Flora in Growing Pigs. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2016, 44, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhaya, S.D.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, I.H. Protected Organic Acid Blends as an Alternative to Antibiotics in Finishing Pigs. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 27, 1600–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffield, K.N.; Becker, G.J.; Smallfield, J.L.; DeRouchey, J.M.; Tokach, M.D.; Woodworth, J.C.; Goodband, R.D.; Lohrmann, T.; Lückstädt, C.; Menegat, M.B.; et al. Evaluating Increasing Levels of Sodium Diformate in Diets for Nursery and Finishing Pigs on Growth Performance, Fecal Dry Matter, and Carcass Characteristics. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2024, 8, txae085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blavi, L.; Solà-Oriol, D.; Llonch, P.; López-Vergé, S.; Martín-Orúe, S.M.; Pérez, J.F. Management and Feeding Strategies in Early Life to Increase Piglet Performance and Welfare around Weaning: A Review. Animals 2021, 11, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, Dillon. P.; O’Doherty, J.V.; Ryan, M.T.; Sweeney, T. Effects of Maternal Probiotics and Piglet Dietary Tryptophan Level on Gastric Function Pre- and Post-Weaning. Agriculture 2025, 15, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Piazuelo, D.; Gardiner, G.E.; Ranjitkar, S.; Bouwhuis, M.A.; Ham, R.; Phelan, J.P.; Marsh, A.; Lawlor, P.G. Maternal Supplementation with Bacillus Altitudinis Spores Improves Porcine Offspring Growth Performance and Carcass Weight. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 127, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heim, G.; Sweeney, T.; O’Shea, C.J.; Doyle, D.N.; O’Doherty, J.V. Effect of Maternal Supplementation with Seaweed Extracts on Growth Performance and Aspects of Gastrointestinal Health of Newly Weaned Piglets after Challenge with Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli K88. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 1955–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowley, A.; O’Doherty, J.V.; Mukhopadhya, A.; Conway, E.; Vigors, S.; Maher, S.; Ryan, M.T.; Sweeney, T. Maternal Supplementation with a Casein Hydrolysate and Yeast Beta-Glucan from Late Gestation through Lactation Improves Gastrointestinal Health of Piglets at Weaning. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rooney, H.B.; O’Driscoll, K.; O’Doherty, J.V.; Lawlor, P.G. Effect of L-Carnitine Supplementation and Sugar Beet Pulp Inclusion in Gilt Gestation Diets on Gilt Live Weight, Lactation Feed Intake, and Offspring Growth from Birth to Slaughter1. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 4208–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, D.P.; O’Doherty, J.V.; Sweeney, T. The Effect of Prebiotic Supplements on the Gastrointestinal Microbiota and Associated Health Parameters in Pigs. Animals 2023, 13, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A.K.; DeRouchey, J.M.; Gebhardt, J.T.; Tokach, M.D.; Woodworth, J.C.; Goodband, R.D.; Loughmiller, J.A.; Kremer, B.T. Effect of Yeast Probiotics in Lactation and Yeast Cell Wall Prebiotic and Bacillus Subtilis Probiotic in Nursery on Lifetime Growth Performance, Immune Response, and Carcass Characteristics. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.T.; Hou, W.X.; Cheng, S.Y.; Shi, B.M.; Shan, A.S. Effects of Dietary Citric Acid on Performance, Digestibility of Calcium and Phosphorus, Milk Composition and Immunoglobulin in Sows during Late Gestation and Lactation. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2014, 191, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, S.M.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, I.H. Analysis of the Effect of Dietary Protected Organic Acid Blend on Lactating Sows and Their Piglets. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2016, 45, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, R.; Kim, I. Effects of Organic Acid and Medium Chain Fatty Acid Blends on the Performance of Sows and Their Piglets. Anim. Sci. J. 2018, 89, 1673–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokach, M.D.; Menegat, M.B.; Gourley, K.M.; Goodband, R.D. Review: Nutrient Requirements of the Modern High-Producing Lactating Sow, with an Emphasis on Amino Acid Requirements. Animal 2019, 13, 2967–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Guo, J.; Guan, W.; Song, J.-J.; Deng, Z.-X.; Cheng, L.; Deng, Y.-L.; Chen, F.; Zhang, S.-H.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; et al. Effect of Pad-Fan Cooling and Dietary Organic Acid Supplementation during Late Gestation and Lactation on Reproductive Performance and Antioxidant Status of Multiparous Sows in Hot Weather. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2018, 50, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampath, V.; Park, J.H.; Pineda, L.; Han, Y.; Kim, I.H. Impact of Synergistic Blend of Organic Acids on the Performance of Late Gestating Sows and Their Offspring. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 21, 1334–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devillers, N.; Le Dividich, J.; Prunier, A. Influence of Colostrum Intake on Piglet Survival and Immunity. Animal 2011, 5, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, G.; Hou, C.; Li, N.; Yu, H.; Shang, L.; Zhang, X.; Trevisi, P.; Yang, F.; et al. Maternal Milk and Fecal Microbes Guide the Spatiotemporal Development of Mucosa-Associated Microbiota and Barrier Function in the Porcine Neonatal Gut. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, Q.; Li, Y.; Tang, Z.; Sun, W.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J.; Sun, Z. Comparative Effects of Dietary Supplementations with Sodium Butyrate, Medium-Chain Fatty Acids, and n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Late Pregnancy and Lactation on the Reproductive Performance of Sows and Growth Performance of Suckling Piglets. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 4256–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblois, J.; Massart, S.; Li, B.; Wavreille, J.; Bindelle, J.; Everaert, N. Modulation of Piglets’ Microbiota: Differential Effects by a High Wheat Bran Maternal Diet during Gestation and Lactation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, D.P.; O’Doherty, J.V.; Sweeney, T. The Effect of Maternal Probiotic or Synbiotic Supplementation on Sow and Offspring Gastrointestinal Microbiota, Health, and Performance. Animals 2023, 13, 2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.; Lozinski, B.; Torres, I.; Davison, S.; Hilbrands, A.; Nelson, E.; Parra-Suescun, J.; Johnston, L.; Gomez, A. Disinfection of Maternal Environments Is Associated with Piglet Microbiome Composition from Birth to Weaning. mSphere 2021, 6, e00663-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xu, J.; Ren, E.; Su, Y.; Zhu, W. Co-Occurrence of Early Gut Colonization in Neonatal Piglets with Microbiota in the Maternal and Surrounding Delivery Environments. Anaerobe 2018, 49, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yu, B.; Sun, J.; Chen, H.; Liu, Z.; Ge, L.; Chen, D. Comparison of Maternal and Neonatal Gut Microbial Community and Function in a Porcine Model. Anim. Biotechnol. 2023, 34, 2972–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huting, A.M.S.; Middelkoop, A.; Guan, X.; Molist, F. Using Nutritional Strategies to Shape the Gastro-Intestinal Tracts of Suckling and Weaned Piglets. Animals 2021, 11, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Li, D.; Ma, Z.; Che, L.; Feng, B.; Fang, Z.; Xu, S.; Zhuo, Y.; Li, J.; Hua, L.; et al. Maternal Tributyrin Supplementation in Late Pregnancy and Lactation Improves Offspring Immunity, Gut Microbiota, and Diarrhea Rate in a Sow Model. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1142174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Øverland, M.; Bikker, P.; Fledderus, J. Potassium Diformate in the Diet of Reproducing Sows: Effect on Performance of Sows and Litters. Livest. Sci. 2009, 122, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, B.; Park, J.W.; Kim, I.H. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Supplementing Micro-Encapsulated Organic Acids and Essential Oils in Diets for Sows and Suckling Piglets. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 15, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.D.; Lindemann, M.D.; Monegue, H.J.; Monegue, J.S. The Effect of Coated Sodium Butyrate Supplementation in Sow and Nursery Diets on Lactation Performance and Nursery Pig Growth Performance. Livest. Sci. 2017, 195, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagómez-Estrada, S.; Melo-Durán, D.; Van Kuijk, S.; Pérez, J.F.; Solà-Oriol, D. Specialized Feed-Additive Blends of Short- and Medium-Chain Fatty Acids Improve Sow and Pig Performance During Nursery and Post-Weaning Phase. Animals 2024, 14, 3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, S.; Sweeney, T.; Vigors, S.; McDonald, M.; O’Doherty, J.V. Effects of Organic Acid-Preserved Cereal Grains in Sow Diets during Late Gestation and Lactation on the Performance and Faecal Microbiota of Sows and Their Offspring. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 16, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Huang, X.; Fang, S.; Xin, W.; Huang, L.; Chen, C. Uncovering the Composition of Microbial Community Structure and Metagenomics among Three Gut Locations in Pigs with Distinct Fatness. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropp, C.; Le Corf, K.; Relizani, K.; Tambosco, K.; Martinez, C.; Chain, F.; Rawadi, G.; Langella, P.; Claus, S.P.; Martin, R. The Keystone Commensal Bacterium Christensenella Minuta DSM 22607 Displays Anti-Inflammatory Properties Both in Vitro and in Vivo. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Production Stage | Organic Acid | Effects on Intestinal Health and Digestive Function | Effects on Growth Performance | Ref. |

| Exp. 1 and 2: Growing Exp. 3: Weaning | Organic acid-preserved grain (57% formic acid blend) |

|

|

[35] |

| Weaning (7-22 kg) | Organic acid-preserved grain (65% propionic acid blend) |

|

|

[195] |

| Weaning (7-21 kg) | Organic acid-preserved grain (65% propionic acid blend) |

|

|

[196] |

| Weaning (7-24 kg) | Organic acid-preserved grain (65% propionic acid blend) |

|

|

[197] |

| Weaning (7-23 kg) | Organic acid-preserved grain (65% propionic acid blend) |

|

|

[198] |

| Suckling to Slaughter (3-120 kg) |

Organic acid-preserved grain (65% propionic acid blend) |

|

|

[199] |

| Production Stage | Organic Acid and Inclusion Level | Effects on Intestinal Health and Digestive Function | Effects on Growth Performance | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weaning (7-26 kg) |

|

|

|

[216] |

| Weaning (9-18 kg) | Ca-formate, Ca-lactate, lauric, myristic, and capric acid and citric acid blend (0.3%) |

|

|

[221] |

| Weaning (8-32 kg) |

|

|

|

[222] |

| Weaning (6-12 kg) | Fumaric, citric, malic, caprylic and capric acids blend (0.2% or 0.4%) |

|

|

[226] |

| Weaning (6-13 kg) | Sodium butyrate (0.05 and 0.1%) |

|

|

[230] |

| Weaning (9-20 kg) |

|

|

|

[233] |

| Weaning (7-28 kg) | Formic acid (0.14 or 0.64%) |

|

|

[234] |

| Weaning (8-18 kg) | Butryic, fumaric and benzoic acid blend (0.5 and 1.0%) |

|

|

[243] |

| Weaning (8-16 kg) |

|

|

|

[244] |

| Weaning (8-13 kg) |

|

|

|

[245] |

| Exp. 1: Weaning(7-24 kg) |

|

|

|

[246] |

| Exp. 2: Weaning(7-24 kg) |

|

|

|

|

| Weaning (6-20 kg) | Sorbic, benzoic, butyric, capric, caprylic, and lauric acid blend (0.2%) |

|

|

[247] |

| Weaning (9-20 kg) | Benzoic acid, Ca-formate, fumaric acid blend (0.15%) |

|

|

[248] |

| Weaning (7-25 kg) | Fumaric, citric, malic, caprylic and capric acids blend (0.1% or 0.2%) |

|

|

[249] |

| Weaning (5-24 kg) |

|

|

|

[250] |

| Growing (19-28 kg) | Benzoic acid (0.5%) |

|

|

[231] |

| Growing (23-50 kg) | Fumaric, citric, malic, caprylic and capric acid blend (0.1% or 0.2%) |

|

|

[251] |

| Growing (23-54 kg) | Fumaric, citric, malic, caprylic and capric acid blend (0.1%, 0.2% or 0.4%) |

|

|

[252] |

| Finishing (48-93 kg) | Fumaric, citric, malic, caprylic and capric acid blend (0.2%) |

|

|

[134] |

| Finishing (50-117 kg) | Fumaric, citric, malic, caprylic and capric acid blend (0.1% or 0.2%) |

|

|

[253] |

| Exp. 1: Weaning (6-22 kg) Exp 2: Grow-Finishing (24-140 kg) |

Sodium diformate Exp 1: (0.4%, 0.6%, 0.8%, 1% or 1.2%) Exp 2: (0.25%, 0.5%, or 0.75%) |

Exp 1:

|

|

[254] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).