Submitted:

04 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

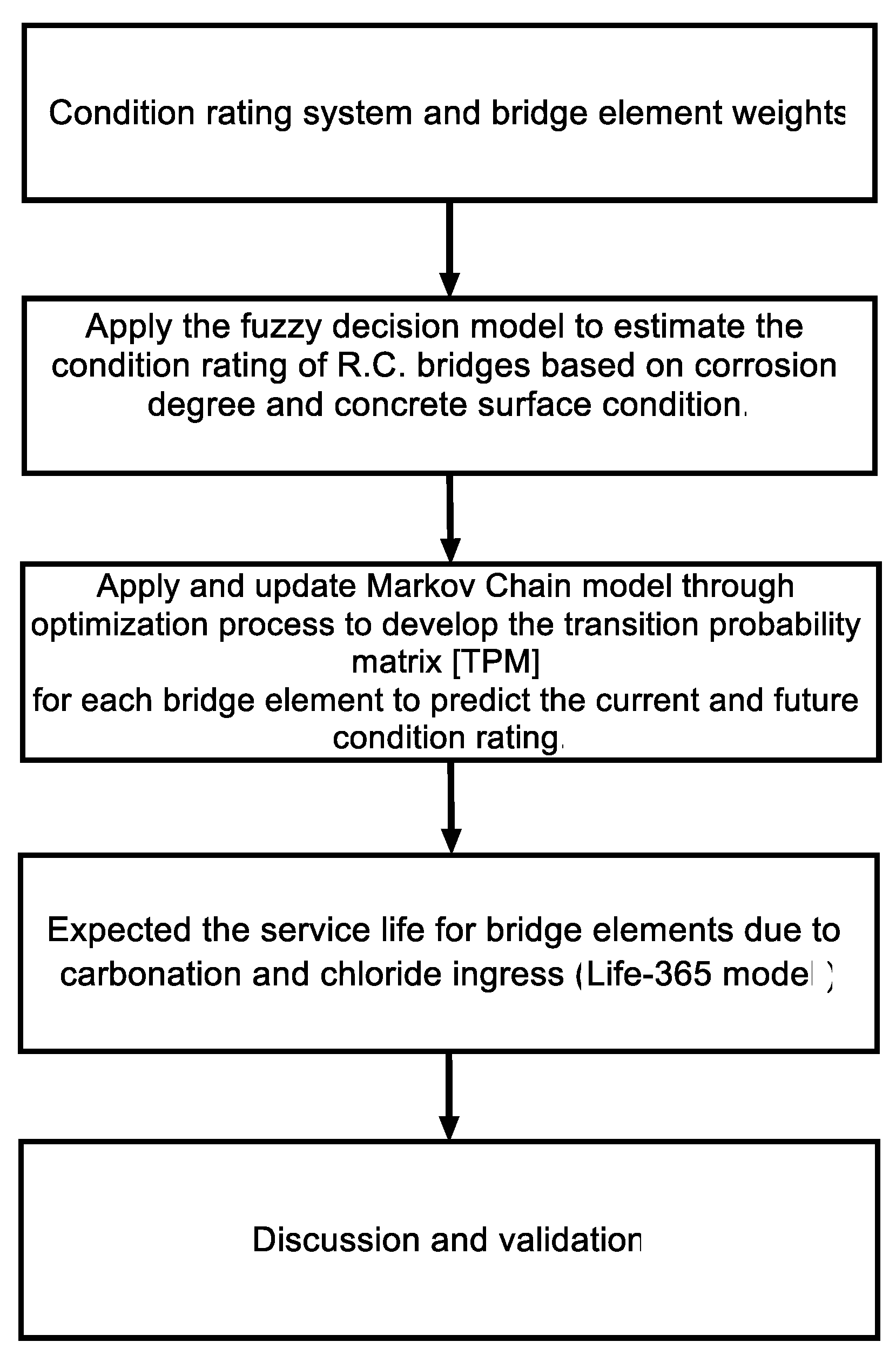

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Method Overview

2.1. Condition Rating System and Bridge Element Weights

2.2. Predicting the Condition Rating of Reinforced Concrete Bridges by Fuzzy Decision Model

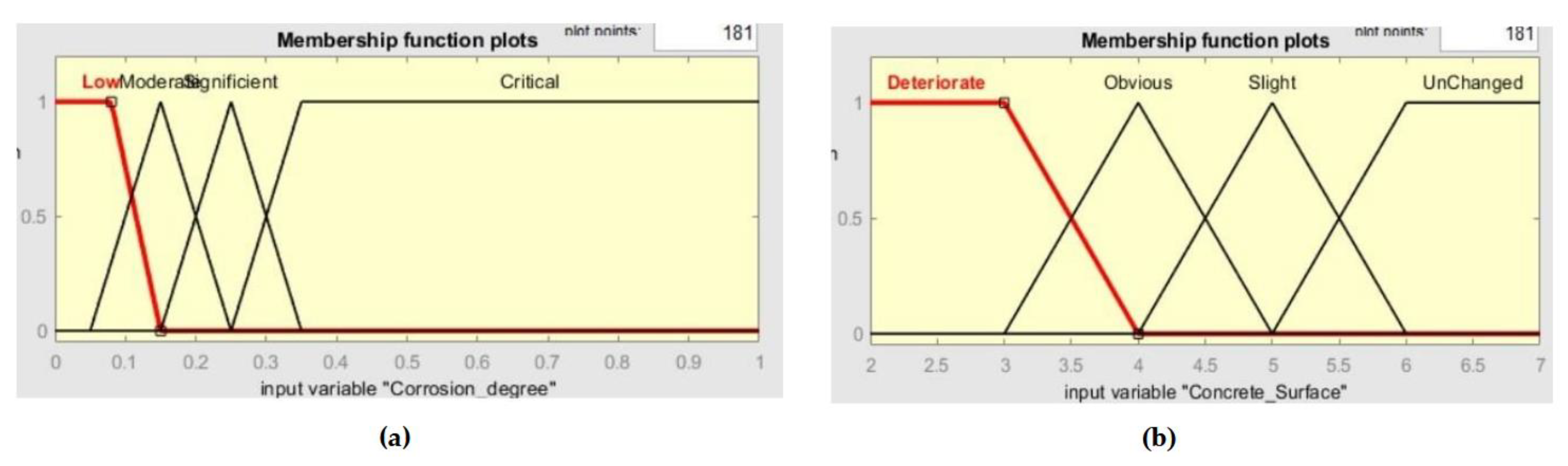

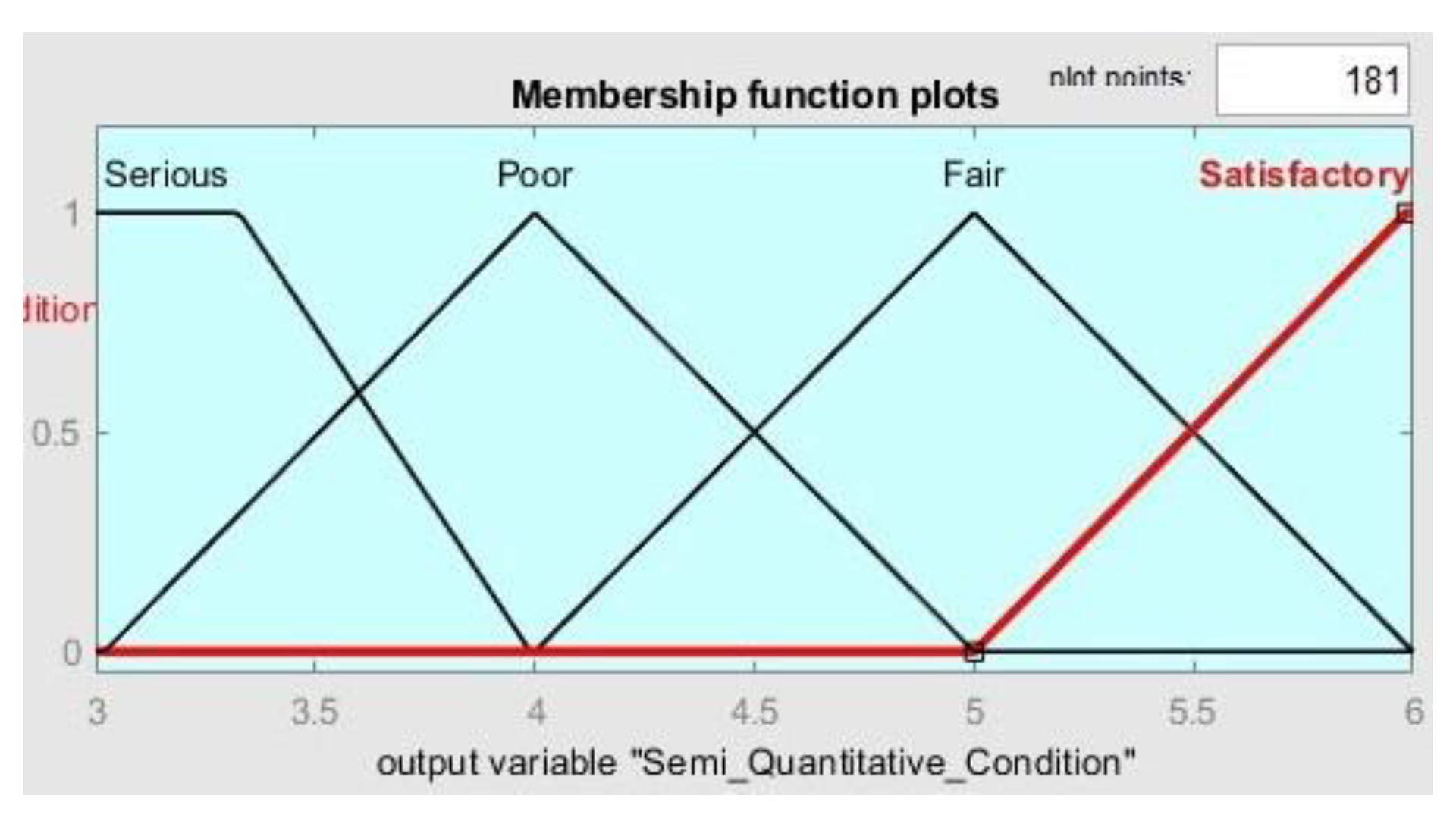

2.2.1. The Membership Functions

- First case:

- Second case:

- Third case:

2.2.2. Applying Fuzzy Decision Rules

2.3. Predicting the Condition Rating of Reinforced Concrete Bridges by Markov Chain Model

2.3.1. Spreadsheet Modelling for Markov Chains

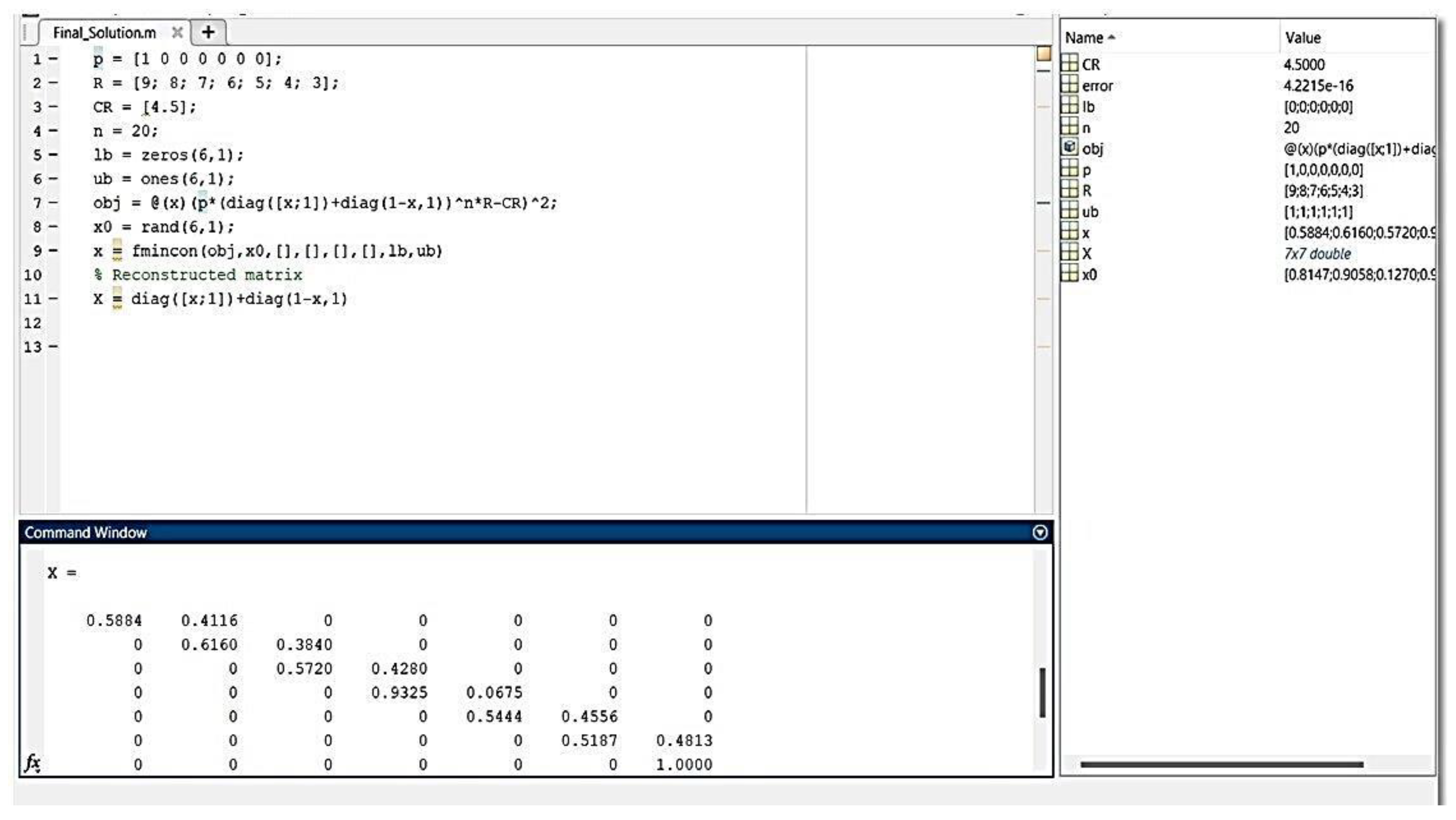

2.3.2. Optimizing [TPM] Probabilities

2.3.3. Objective Function

2.3.4. Variables

2.4. Expected the Service Life for the Reinforced Concrete Bridge Elements

2.4.1. Service Life Prediction Based on Carbonation Attack

2.4.2. Life-365 Model for Service Life Prediction Due to Chloride-Induced

3. Discussion & Validation

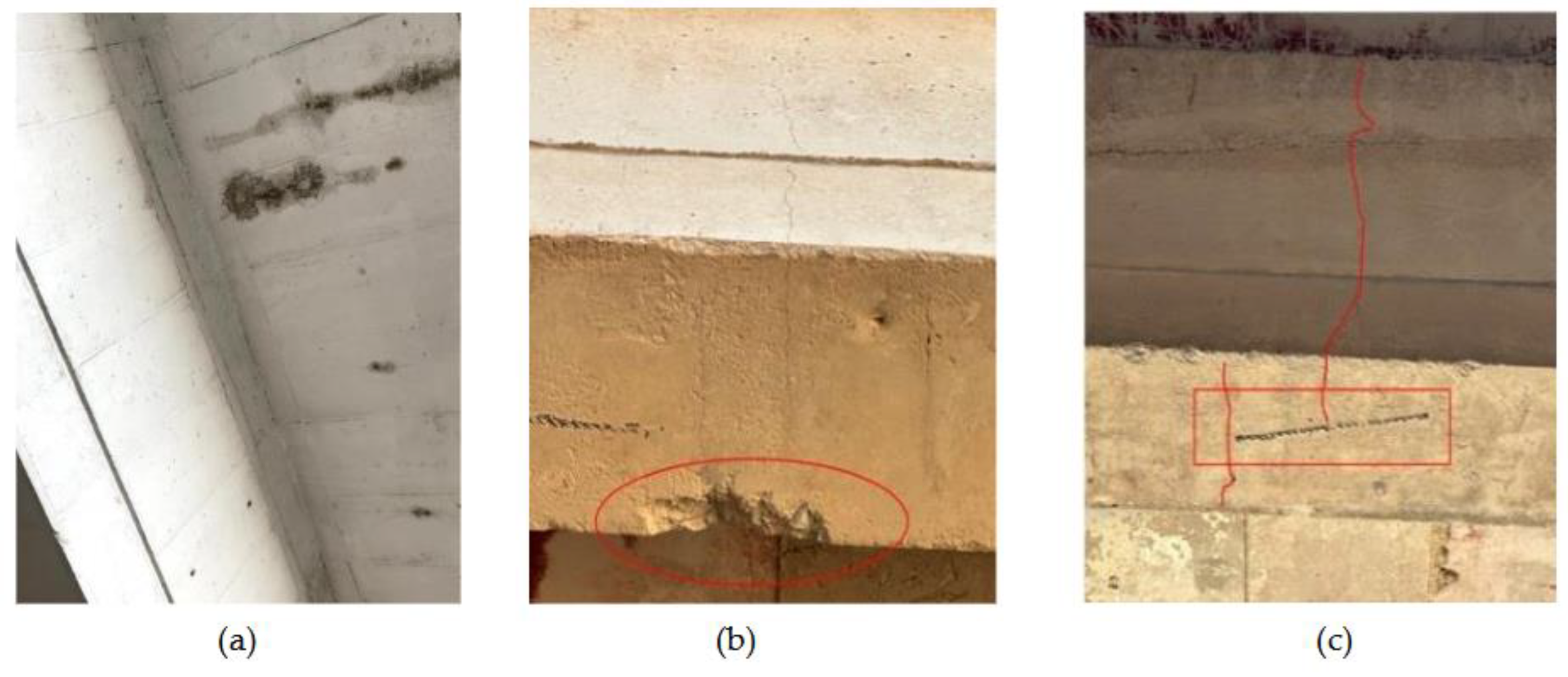

3.1. Data Gathering, Historical Data, Inventory of R.C. Bridge Elements

3.3. Expected the Service Life for Bridge Elements Due to Carbonation and Chloride-Induced

3.3.1. Corrosion Due to Carbonation for Bridge Elements

3.3.2. Chloride Induced Corrosion of Reinforcing Steel

3.4. Condition Assessment for R.C Bridges Due to Dual Approach, 1) Fuzzy Logic Analysis Technique, 2) Markov Chain Model

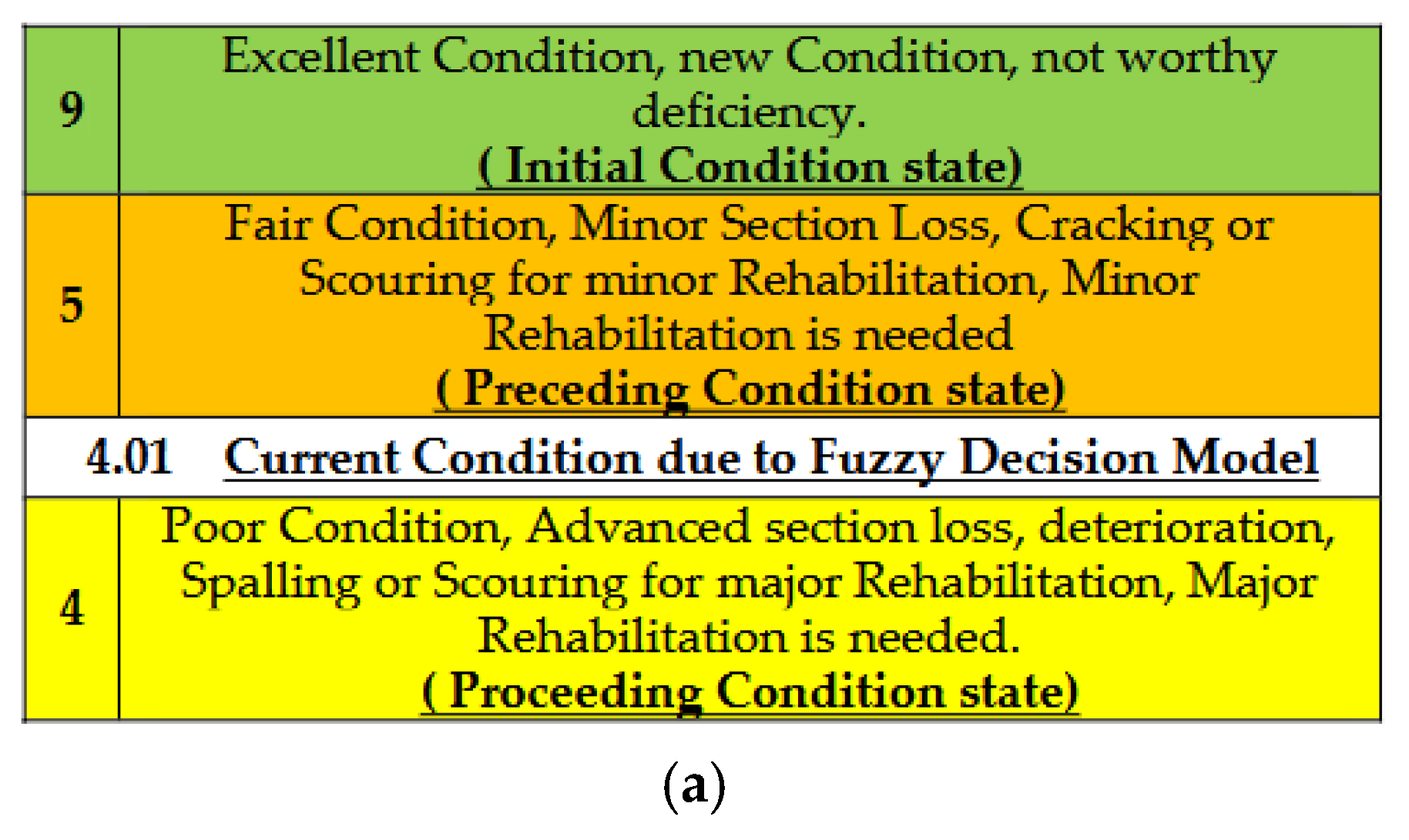

3.4.1. Fuzzy Decision Model

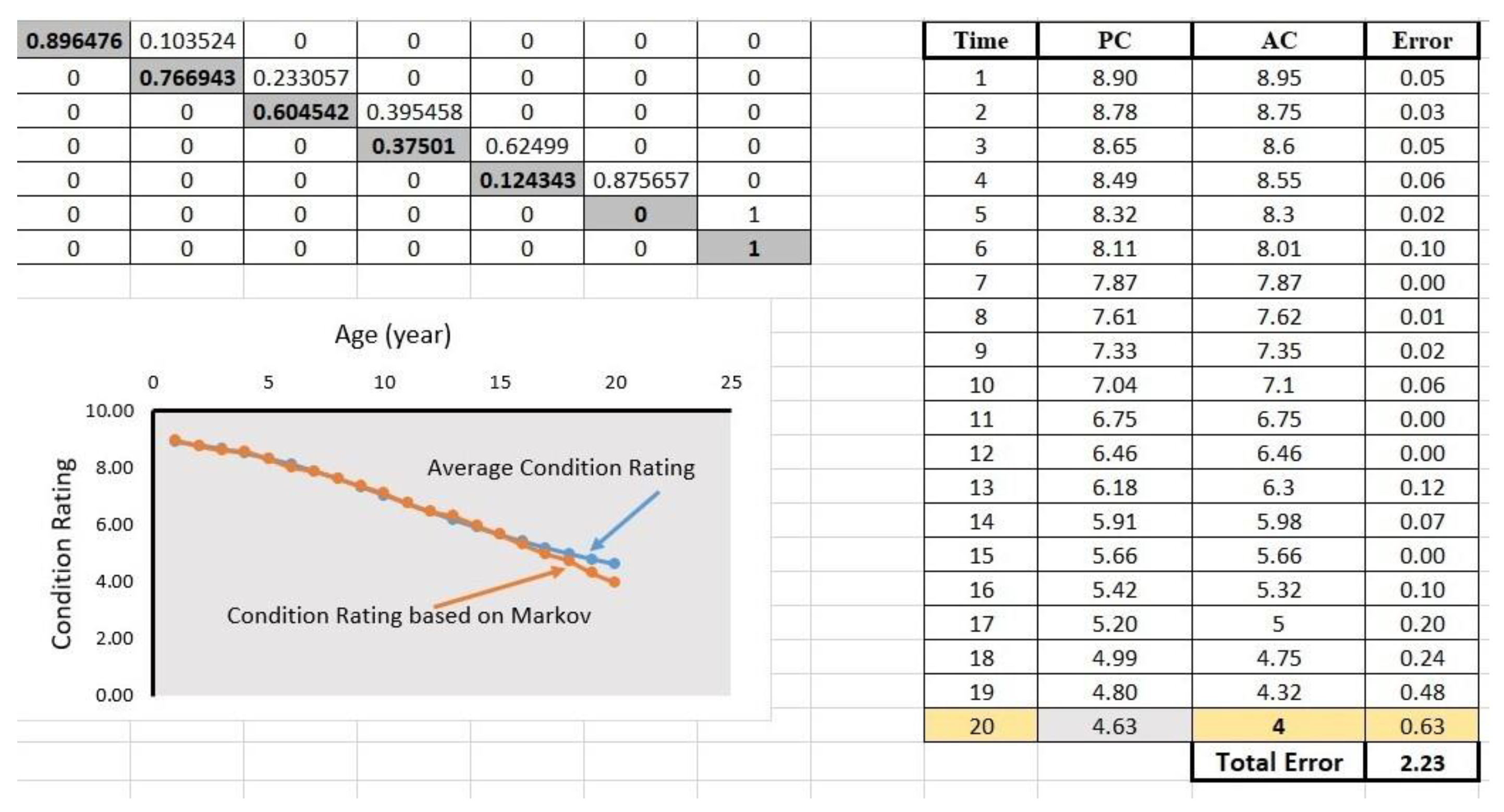

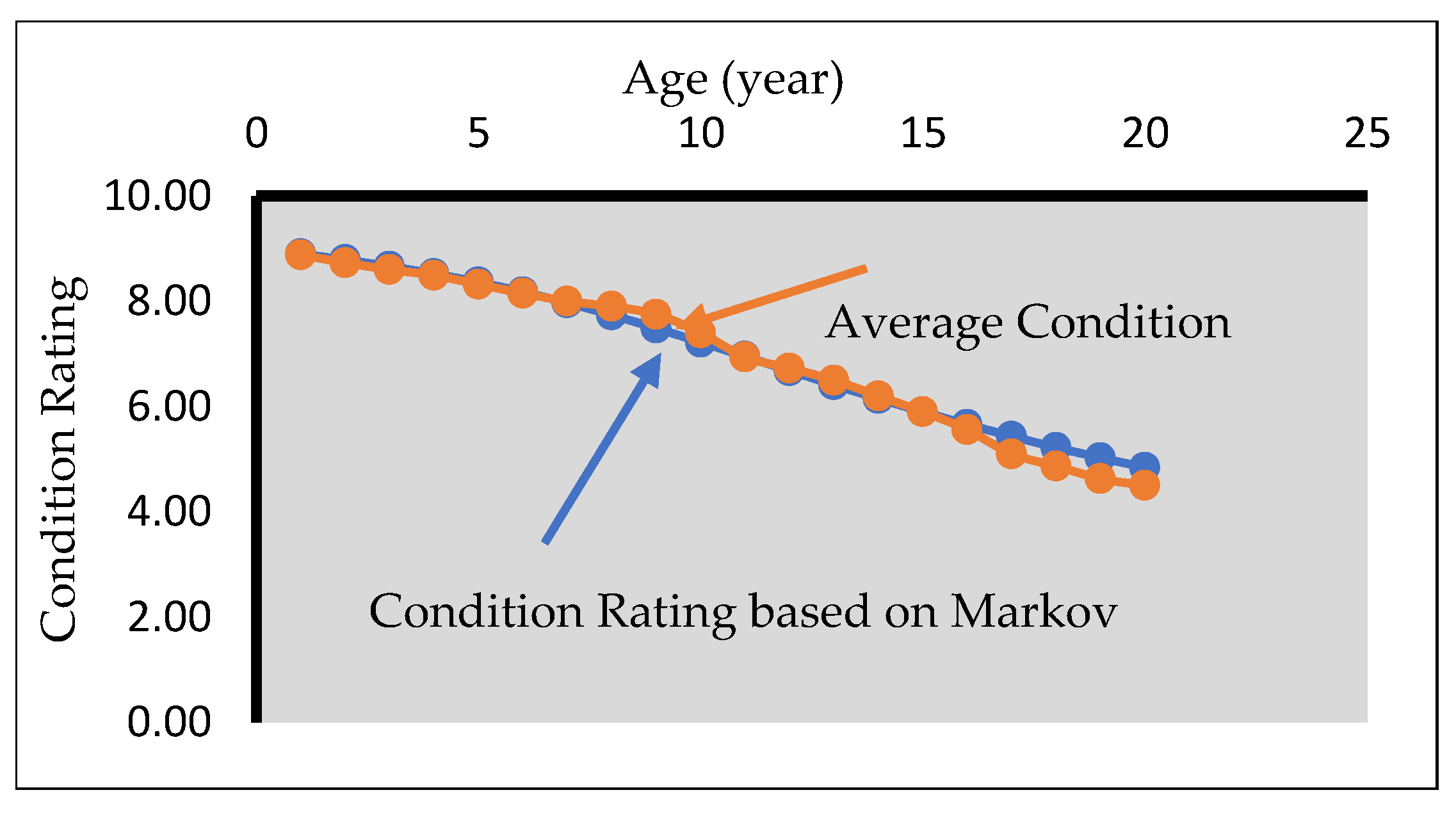

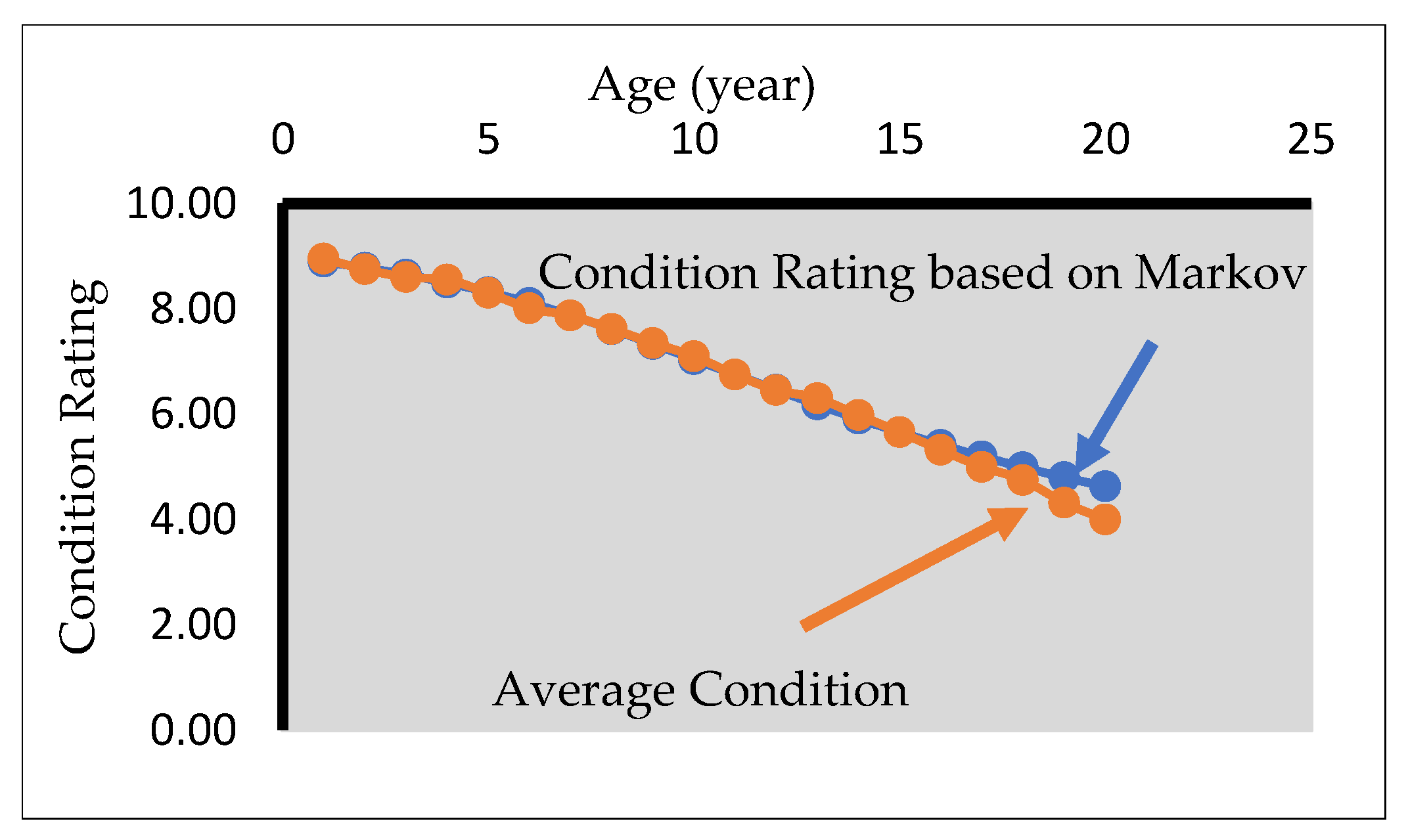

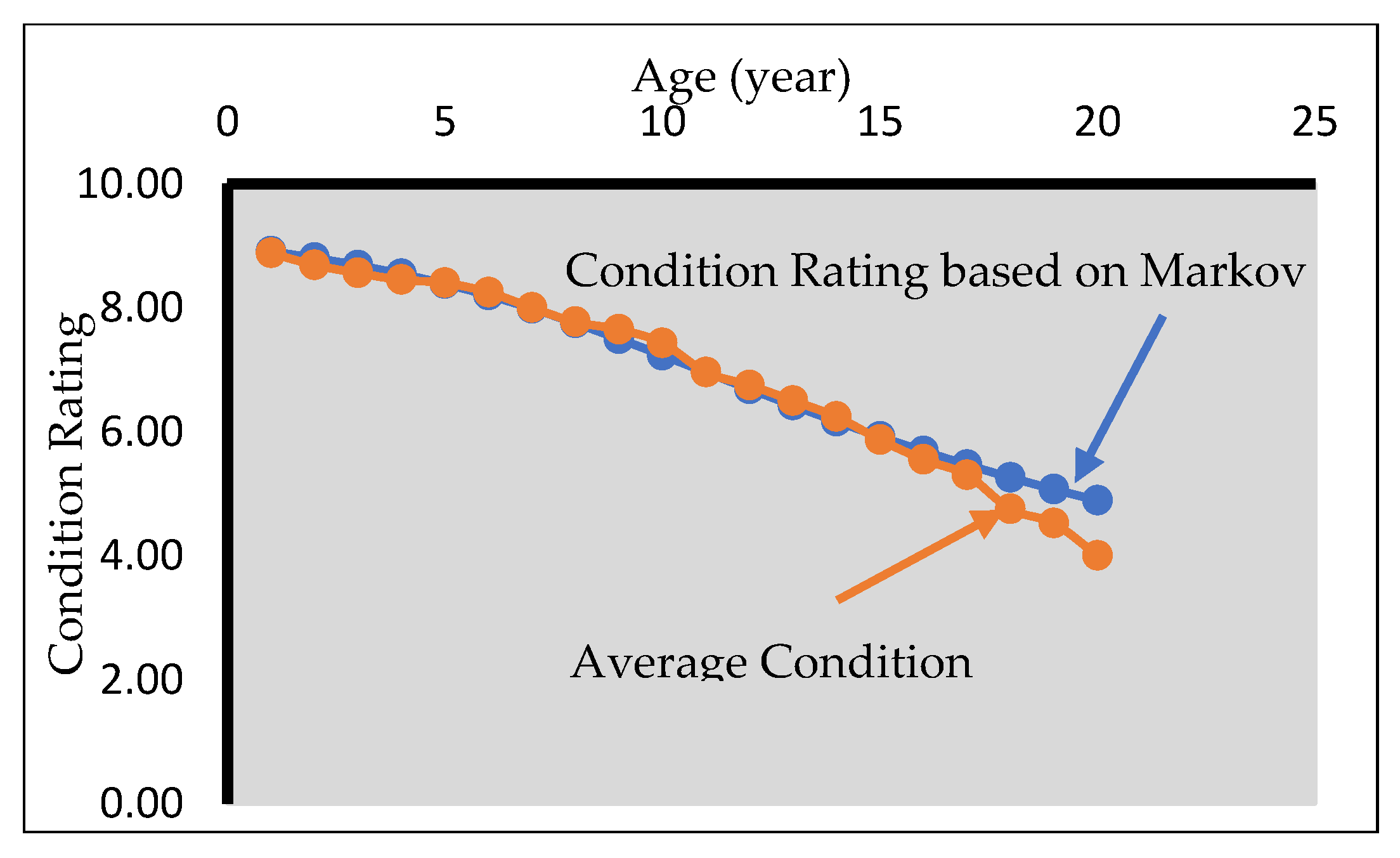

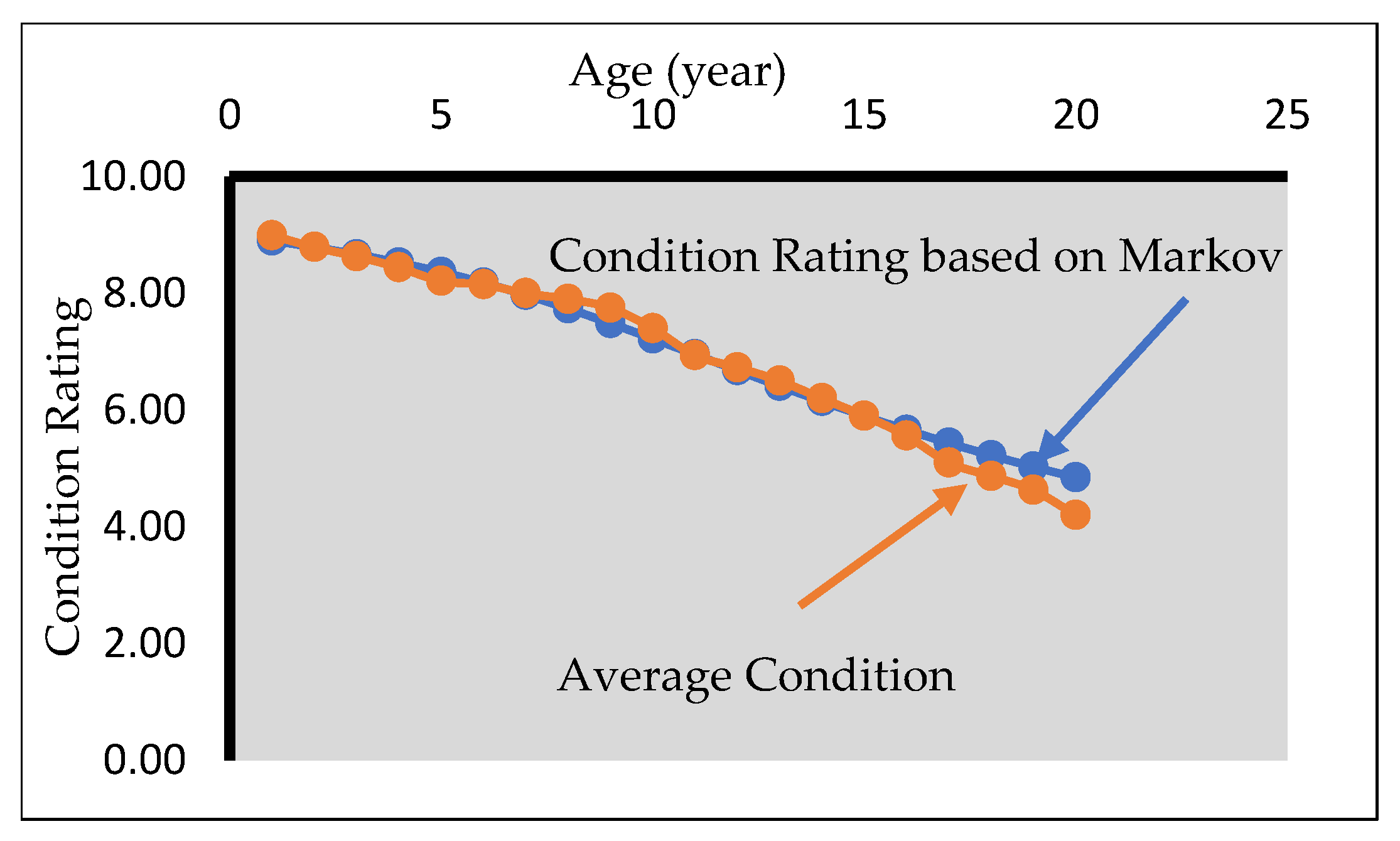

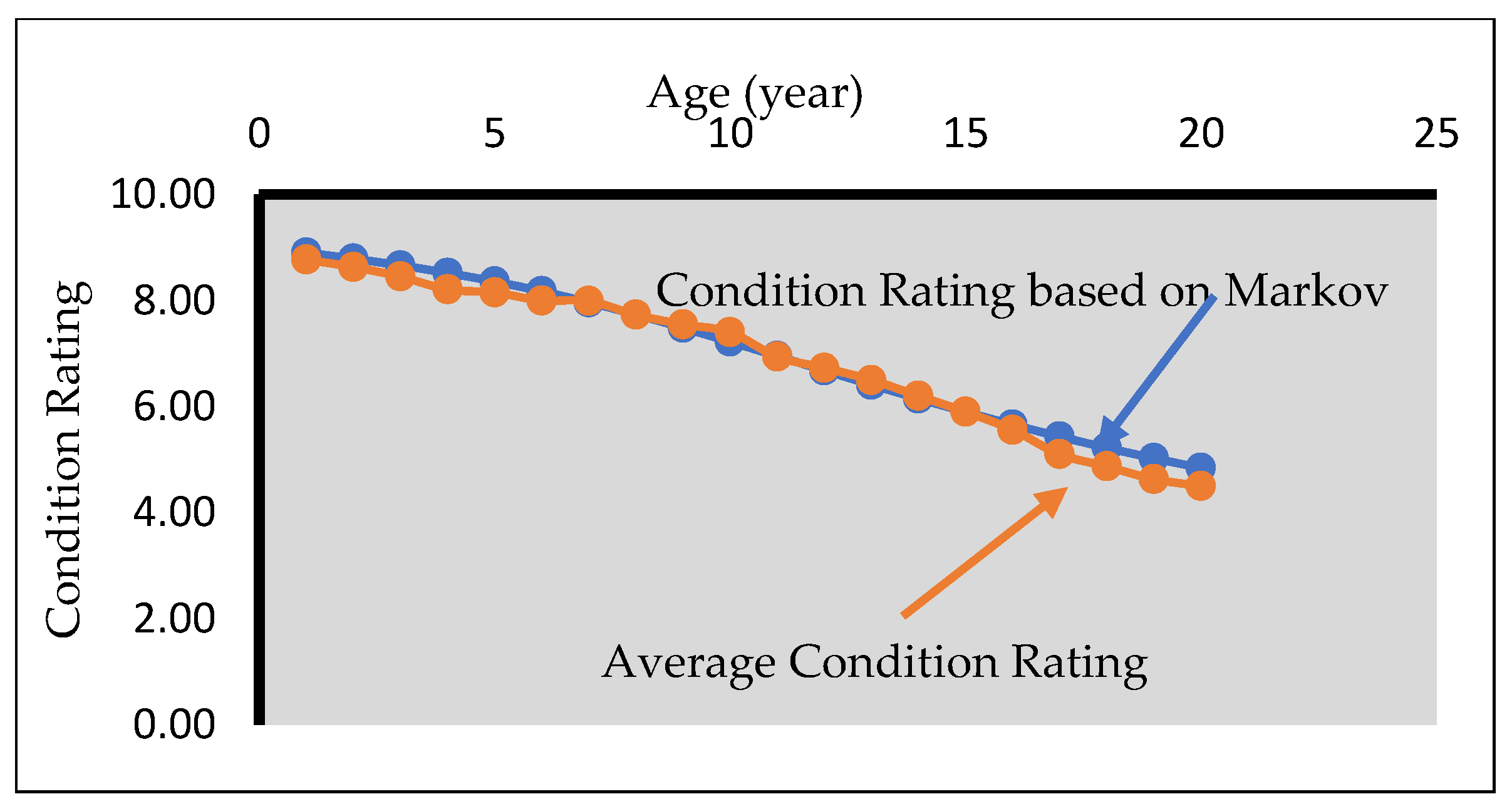

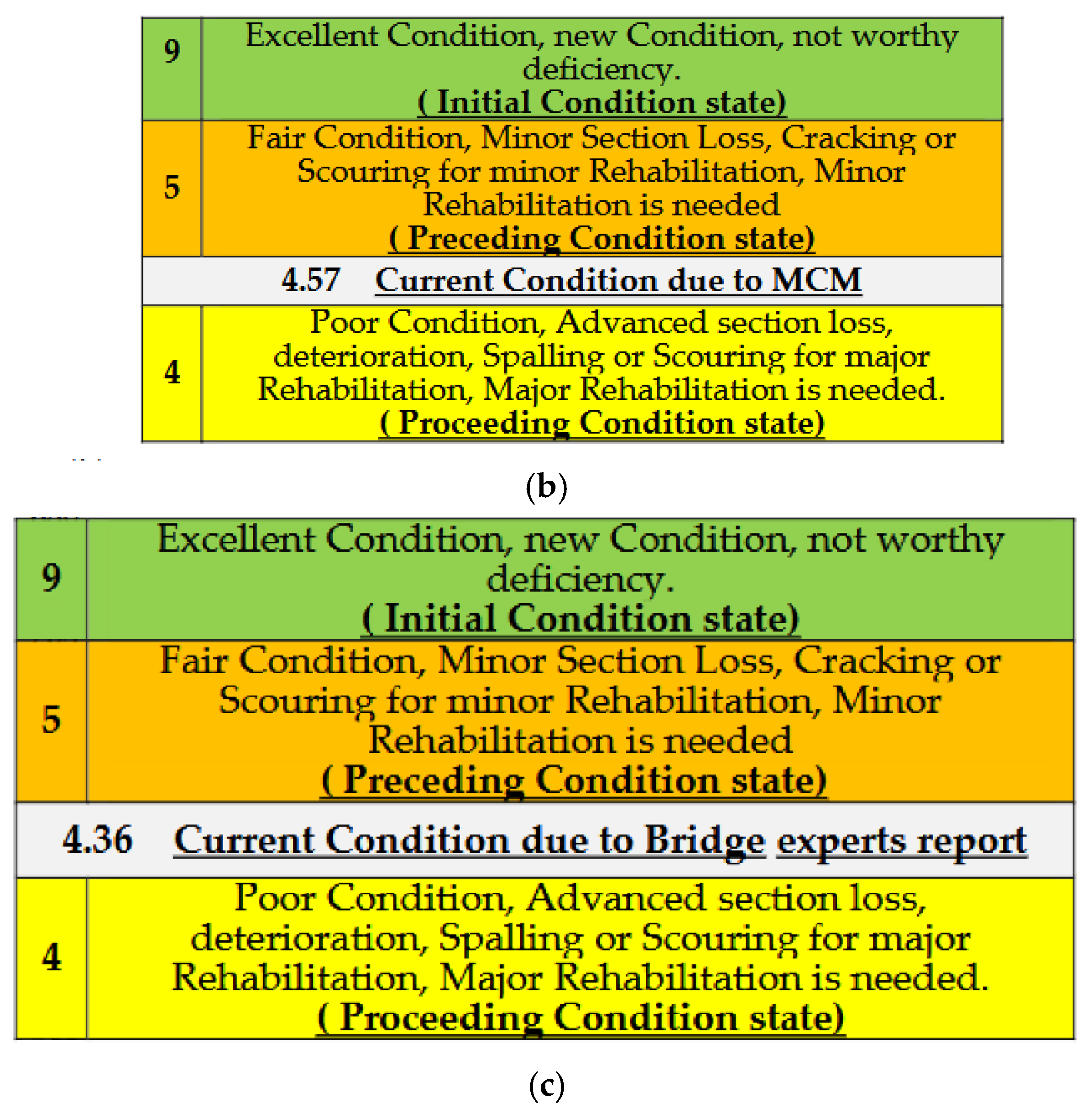

3.4.2. Markov Chain Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| MRR | Maintenance, Repair, and Replacement |

| RC | Reinforced concrete |

| BMS | Bridge Management System |

| GPR | Ground Penetrating Radar |

| AASHTO | American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials |

| GARB | General Authority for Roads and Bridges |

| MCM | Markov Chain Modelling |

| WEM | Weight Evaluation Method |

| BCR | Bridge Condition Rating |

| TPM | Transition Probability Matrix |

| FHWA | Federal Highway Administration classification system |

| NY | New York ranking system |

Appendix A

| Element Parameter |

S1L1 | S6L1 | G1L1 | G2L1 | G3L1 | G4L1 | G5L1 | D1L1 | AB1 | AB2 | W21 | W22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Evaluation | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| pH-value | 7.38 | 12.28 | 7.28 | 13.41 | 13.12 | 7.18 | 13.66 | 8 | 13.99 | 11.98 | 12.71 | 13.12 | |

| Rate of corrosion due to pH (mm/yr.) | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.042 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.095 | 0.06 | 0.042 | |

| Concrete resistivity (ohm.cm) | 8000 | 11500 | 8000 | 11800 | 11800 | 8000 | 11800 | 8500 | 11800 | 11200 | 11500 | 11800 | |

| C.C (mm) | 15 | 15 | 15 | 18 | 15 | 15 | 18 | 12 | 18 | 18 | 15 | 15 | |

| Measured carbonation test (mm) (Laboratory test) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Uncarbonated depth (dc)=min cover-carbonation depth | 10 | 10 | 10 | 13 | 10 | 10 | 13 | 10 | 13 | 13 | 10 | 10 | |

| Steel Diameter | 14 | 14 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 25 | 25 | 18 | 18 | |

| T1: initiation period (years) | 25 | 25 | 25 | 42.25 | 25 | 25 | 42.25 | 25 | 42.25 | 42.25 | 25 | 25 | |

| T2: Propagation Period (years) | 0.659 | 1.071 | 0.218 | 2.182 | 1.299 | 0.218 | 3.273 | 0.175 | 5.760 | 0.606 | 1.111 | 1.587 | |

| Tt= T1+T2 (Due to carbonation) | 25.66 | 26.07 | 25.22 | 44.43 | 26.30 | 25.22 | 45.52 | 25.17 | 48.01 | 42.86 | 26.11 | 26.59 | |

| Service life due toChloride Induced (Life -365) | 26.80 | 28.10 | 23.50 | 23.60 | 20.30 | 21.30 | 26.30 | 24.50 | 39.60 | 38.40 | 23.80 | 27.70 |

| Time | Predicted CR | Actual CR | Error |

| 1 | 8.90 | 8.95 | 0.05 |

| 2 | 8.78 | 8.75 | 0.03 |

| 3 | 8.65 | 8.6 | 0.05 |

| 4 | 8.49 | 8.55 | 0.06 |

| 5 | 8.32 | 8.3 | 0.02 |

| 6 | 8.11 | 8.01 | 0.10 |

| 7 | 7.87 | 7.87 | 0.00 |

| 8 | 7.61 | 7.62 | 0.01 |

| 9 | 7.33 | 7.35 | 0.02 |

| 10 | 7.04 | 7.1 | 0.06 |

| 11 | 6.75 | 6.75 | 0.00 |

| 12 | 6.46 | 6.46 | 0.00 |

| 13 | 6.18 | 6.3 | 0.12 |

| 14 | 5.91 | 5.98 | 0.07 |

| 15 | 5.66 | 5.66 | 0.00 |

| 16 | 5.42 | 5.32 | 0.10 |

| 17 | 5.20 | 5 | 0.20 |

| 18 | 4.99 | 4.75 | 0.24 |

| 19 | 4.80 | 4.32 | 0.48 |

| 20 | 4.63 | 4 | 0.63 |

| 21 | 4.47 | ||

| 22 | 4.32 | ||

| 23 | 4.19 | ||

| 24 | 4.07 | ||

| 25 | 3.97 | ||

| 26 | 3.87 | ||

| 27 | 3.78 | ||

| 28 | 3.70 | ||

| 29 | 3.63 | ||

| 30 | 3.57 | ||

| 31 | 3.51 | ||

| 32 | 3.46 | ||

| 33 | 3.41 | ||

| 34 | 3.37 | ||

| 35 | 3.33 | ||

| 36 | 3.30 | ||

| 37 | 3.27 | ||

| 38 | 3.24 | ||

| 39 | 3.21 | ||

| 40 | 3.19 | ||

| 41 | 3.17 | ||

| 42 | 3.15 | ||

| 43 | 3.14 | ||

| 44 | 3.12 | ||

| 45 | 3.11 | ||

| 46 | 3.10 | ||

| 47 | 3.09 | ||

| 48 | 3.08 | ||

| 49 | 3.07 | ||

| 50 | 3.06 | ||

| 51 | 3.06 | ||

| 52 | 3.05 | ||

| 53 | 3.05 | ||

| 54 | 3.04 | ||

| 55 | 3.04 | ||

| 56 | 3.03 | ||

| 57 | 3.03 | ||

| 58 | 3.03 | ||

| 59 | 3.02 | ||

| 60 | 3.02 | ||

| 61 | 3.02 | ||

| Time | Predicted CR | Actual CR | Error |

| 62 | 3.02 | ||

| 63 | 3.02 | ||

| 64 | 3.01 | ||

| 65 | 3.01 | ||

| 66 | 3.01 | ||

| 67 | 3.01 | ||

| 68 | 3.01 | ||

| 69 | 3.01 | ||

| 70 | 3.01 | ||

| 71 | 3.01 | ||

| 72 | 3.01 | ||

| 73 | 3.01 | ||

| 74 | 3.00 |

| Time | Predicted CR | Actual CR | Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.90 | 8.88 | 0.02 |

| 2 | 8.79 | 8.73 | 0.06 |

| 3 | 8.66 | 8.6 | 0.06 |

| 4 | 8.52 | 8.49 | 0.03 |

| 5 | 8.36 | 8.32 | 0.04 |

| 6 | 8.18 | 8.15 | 0.03 |

| 7 | 7.97 | 8 | 0.03 |

| 8 | 7.74 | 7.9 | 0.16 |

| 9 | 7.49 | 7.75 | 0.26 |

| 10 | 7.22 | 7.4 | 0.18 |

| 11 | 6.95 | 6.94 | 0.01 |

| 12 | 6.68 | 6.73 | 0.05 |

| 13 | 6.41 | 6.5 | 0.09 |

| 14 | 6.15 | 6.2 | 0.05 |

| 15 | 5.90 | 5.9 | 0.00 |

| 16 | 5.66 | 5.56 | 0.10 |

| 17 | 5.44 | 5.1 | 0.34 |

| 18 | 5.22 | 4.87 | 0.35 |

| 19 | 5.03 | 4.63 | 0.40 |

| 20 | 4.84 | 4.5 | 0.34 |

| 21 | 4.67 | ||

| 22 | 4.52 | ||

| 23 | 4.38 | ||

| 24 | 4.25 | ||

| 25 | 4.13 | ||

| 26 | 4.02 | ||

| 27 | 3.92 | ||

| 28 | 3.83 | ||

| 29 | 3.75 | ||

| 30 | 3.68 | ||

| 31 | 3.61 | ||

| 32 | 3.55 | ||

| 33 | 3.49 | ||

| 34 | 3.45 | ||

| 35 | 3.40 | ||

| 36 | 3.36 | ||

| 37 | 3.32 | ||

| 38 | 3.29 | ||

| 39 | 3.26 | ||

| 40 | 3.24 | ||

| 41 | 3.21 | ||

| 42 | 3.19 | ||

| 43 | 3.17 | ||

| 44 | 3.16 | ||

| 45 | 3.14 | ||

| 46 | 3.13 | ||

| 47 | 3.11 | ||

| 48 | 3.10 | ||

| 49 | 3.09 | ||

| 50 | 3.08 | ||

| 51 | 3.07 | ||

| 52 | 3.07 | ||

| 53 | 3.06 | ||

| 54 | 3.05 | ||

| 55 | 3.05 | ||

| 56 | 3.04 | ||

| 57 | 3.04 | ||

| 58 | 3.04 | ||

| 59 | 3.03 | ||

| 60 | 3.03 | ||

| 61 | 3.03 | ||

| 62 | 3.02 | ||

| 63 | 3.02 | ||

| Time | Predicted CR | Actual CR | Error |

| 64 | 3.02 | ||

| 65 | 3.02 | ||

| 66 | 3.02 | ||

| 67 | 3.01 | ||

| 68 | 3.01 | ||

| 69 | 3.01 | ||

| 70 | 3.01 | ||

| 71 | 3.01 | ||

| 72 | 3.01 | ||

| 73 | 3.01 | ||

| 74 | 3.01 | ||

| 75 | 3.01 | ||

| 76 | 3.01 | ||

| 77 | 3.00 |

| Time | Predicted CR | Actual CR | Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.91 | 8.88 | 0.03 |

| 2 | 8.80 | 8.69 | 0.11 |

| 3 | 8.68 | 8.56 | 0.12 |

| 4 | 8.54 | 8.45 | 0.09 |

| 5 | 8.38 | 8.4 | 0.02 |

| 6 | 8.20 | 8.25 | 0.05 |

| 7 | 7.99 | 8 | 0.01 |

| 8 | 7.75 | 7.77 | 0.02 |

| 9 | 7.50 | 7.65 | 0.15 |

| 10 | 7.23 | 7.43 | 0.20 |

| 11 | 6.96 | 6.96 | 0.00 |

| 12 | 6.69 | 6.75 | 0.06 |

| 13 | 6.42 | 6.5 | 0.08 |

| 14 | 6.17 | 6.24 | 0.07 |

| 15 | 5.92 | 5.87 | 0.05 |

| 16 | 5.69 | 5.55 | 0.14 |

| 17 | 5.47 | 5.3 | 0.17 |

| 18 | 5.26 | 4.75 | 0.51 |

| 19 | 5.07 | 4.52 | 0.55 |

| 20 | 4.89 | 4 | 0.89 |

| 21 | 4.73 | ||

| 22 | 4.58 | ||

| 23 | 4.44 | ||

| 24 | 4.31 | ||

| 25 | 4.19 | ||

| 26 | 4.09 | ||

| 27 | 3.99 | ||

| 28 | 3.90 | ||

| 29 | 3.82 | ||

| 30 | 3.82 | ||

| 31 | 3.68 | ||

| 32 | 3.62 | ||

| 33 | 3.56 | ||

| 34 | 3.51 | ||

| 35 | 3.46 | ||

| 36 | 3.42 | ||

| 37 | 3.38 | ||

| 38 | 3.35 | ||

| Time | Predicted CR | Actual CR | Error |

| 39 | 3.32 | ||

| 40 | 3.29 | ||

| 41 | 3.26 | ||

| 42 | 3.24 | ||

| 43 | 3.21 | ||

| 44 | 3.20 | ||

| 45 | 3.18 | ||

| 46 | 3.16 | ||

| 47 | 3.15 | ||

| 48 | 3.13 | ||

| 49 | 3.12 | ||

| 50 | 3.11 | ||

| 51 | 3.10 | ||

| 52 | 3.09 | ||

| 53 | 3.08 | ||

| 54 | 3.07 | ||

| 55 | 3.07 | ||

| 56 | 3.06 | ||

| 57 | 3.06 | ||

| 58 | 3.05 | ||

| 59 | 3.05 | ||

| 60 | 3.04 | ||

| 61 | 3.04 | ||

| 62 | 3.03 | ||

| 63 | 3.03 | ||

| 64 | 3.03 | ||

| 65 | 3.03 | ||

| 66 | 3.02 | ||

| 67 | 3.02 | ||

| 68 | 3.02 | ||

| 69 | 3.02 | ||

| 70 | 3.02 | ||

| 71 | 3.01 | ||

| 72 | 3.01 | ||

| 73 | 3.01 | ||

| 74 | 3.01 | ||

| 75 | 3.01 | ||

| 76 | 3.01 | ||

| 77 | 3.01 | ||

| 78 | 3.01 | ||

| 79 | 3.01 | ||

| 80 | 3.01 | ||

| 81 | 3.01 | ||

| 82 | 3.01 | ||

| 83 | 3.01 | ||

| 84 | 3.00 |

| Time | Predicted CR | Actual CR | Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.90 | 8.99 | 0.09 |

| 2 | 8.79 | 8.79 | 0.00 |

| 3 | 8.67 | 8.63 | 0.04 |

| 4 | 8.52 | 8.44 | 0.08 |

| 5 | 8.36 | 8.21 | 0.15 |

| 6 | 8.18 | 8.15 | 0.03 |

| 7 | 7.97 | 8 | 0.03 |

| 8 | 7.74 | 7.9 | 0.16 |

| 9 | 7.49 | 7.75 | 0.26 |

| 10 | 7.22 | 7.4 | 0.18 |

| 11 | 6.95 | 6.94 | 0.01 |

| 12 | 6.68 | 6.73 | 0.05 |

| 13 | 6.41 | 6.5 | 0.09 |

| 14 | 6.15 | 6.2 | 0.05 |

| 15 | 5.90 | 5.9 | 0.00 |

| 16 | 5.66 | 5.56 | 0.10 |

| 17 | 5.44 | 5.1 | 0.34 |

| 18 | 5.23 | 4.87 | 0.36 |

| 19 | 5.03 | 4.63 | 0.40 |

| 20 | 4.85 | 4.2 | 0.65 |

| 21 | 4.68 | ||

| 22 | 4.52 | ||

| 23 | 4.38 | ||

| 24 | 4.25 | ||

| 25 | 4.13 | ||

| 26 | 4.02 | ||

| 27 | 3.93 | ||

| 28 | 3.84 | ||

| 29 | 3.76 | ||

| 30 | 3.68 | ||

| 31 | 3.62 | ||

| 32 | 3.56 | ||

| 33 | 3.50 | ||

| 34 | 3.45 | ||

| 35 | 3.41 | ||

| 36 | 3.37 | ||

| 37 | 3.33 | ||

| 38 | 3.30 | ||

| 39 | 3.27 | ||

| 40 | 3.24 | ||

| 41 | 3.22 | ||

| 42 | 3.20 | ||

| 43 | 3.18 | ||

| 44 | 3.16 | ||

| 45 | 3.14 | ||

| 46 | 3.13 | ||

| 47 | 3.12 | ||

| 48 | 3.11 | ||

| 49 | 3.10 | ||

| 50 | 3.09 | ||

| 51 | 3.08 | ||

| 52 | 3.07 | ||

| 53 | 3.06 | ||

| 54 | 3.06 | ||

| 55 | 3.05 | ||

| 56 | 3.05 | ||

| 57 | 3.04 | ||

| 58 | 3.04 | ||

| 59 | 3.03 | ||

| 60 | 3.03 | ||

| 61 | 3.03 | ||

| 62 | 3.02 | ||

| Time | Predicted CR | Actual CR | Error |

| 63 | 3.02 | ||

| 64 | 3.02 | ||

| 65 | 3.02 | ||

| 66 | 3.02 | ||

| 67 | 3.01 | ||

| 68 | 3.01 | ||

| 69 | 3.01 | ||

| 70 | 3.01 | ||

| 71 | 3.01 | ||

| 72 | 3.01 | ||

| 73 | 3.01 | ||

| 74 | 3.01 | ||

| 75 | 3.01 | ||

| 76 | 3.01 | ||

| 77 | 3.01 | ||

| 78 | 3.00 |

| Time | Predicted CR | Actual CR | Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.90 | 8.77 | 0.13 |

| 2 | 8.79 | 8.63 | 0.16 |

| 3 | 8.66 | 8.45 | 0.21 |

| 4 | 8.52 | 8.21 | 0.31 |

| 5 | 8.36 | 8.15 | 0.21 |

| 6 | 8.17 | 8 | 0.17 |

| 7 | 7.96 | 7.99 | 0.03 |

| 8 | 7.73 | 7.73 | 0.00 |

| 9 | 7.48 | 7.55 | 0.07 |

| 10 | 7.22 | 7.4 | 0.18 |

| 11 | 6.95 | 6.94 | 0.01 |

| 12 | 6.68 | 6.73 | 0.05 |

| 13 | 6.41 | 6.5 | 0.09 |

| 14 | 6.15 | 6.2 | 0.05 |

| 15 | 5.90 | 5.9 | 0.00 |

| 16 | 5.66 | 5.56 | 0.10 |

| 17 | 5.43 | 5.1 | 0.33 |

| 18 | 5.22 | 4.87 | 0.35 |

| 19 | 5.02 | 4.63 | 0.39 |

| 20 | 4.84 | 4.5 | 0.34 |

| 21 | 4.67 | ||

| 22 | 4.52 | ||

| 23 | 4.37 | ||

| 24 | 4.24 | ||

| 25 | 4.13 | ||

| 26 | 4.02 | ||

| 27 | 3.92 | ||

| 28 | 3.83 | ||

| 29 | 3.75 | ||

| 30 | 3.68 | ||

| 31 | 3.61 | ||

| 32 | 3.55 | ||

| 33 | 3.50 | ||

| 34 | 3.45 | ||

| 35 | 3.40 | ||

| 36 | 3.36 | ||

| 37 | 3.33 | ||

| 38 | 3.27 | ||

| 39 | 3.27 | ||

| 40 | 3.24 | ||

| 41 | 3.22 | ||

| Time | Predicted CR | Actual CR | Error |

| 42 | 3.19 | ||

| 43 | 3.18 | ||

| 44 | 3.16 | ||

| 45 | 3.14 | ||

| 46 | 3.13 | ||

| 47 | 3.12 | ||

| 48 | 3.10 | ||

| 49 | 3.09 | ||

| 50 | 3.08 | ||

| 51 | 3.08 | ||

| 52 | 3.07 | ||

| 53 | 3.06 | ||

| 54 | 3.06 | ||

| 55 | 3.05 | ||

| 56 | 3.04 | ||

| 57 | 3.04 | ||

| 58 | 3.04 | ||

| 59 | 3.03 | ||

| 60 | 3.03 | ||

| 61 | 3.03 | ||

| 62 | 3.02 | ||

| 63 | 3.02 | ||

| 64 | 3.02 | ||

| 65 | 3.02 | ||

| 66 | 3.02 | ||

| 67 | 3.01 | ||

| 68 | 3.01 | ||

| 69 | 3.01 | ||

| 70 | 3.01 | ||

| 71 | 3.01 | ||

| 72 | 3.01 | ||

| 73 | 3.01 | ||

| 74 | 3.01 | ||

| 75 | 3.01 | ||

| 76 | 3.01 | ||

| 77 | 3.00 |

References

- General authority for roads and bridges (GARB), Arab Republic of Egypt (July 2015). The project for improvement of the bridge management capacity. Project completion report.

- Figueiredo, E., Moldovan, I., & Marques, M. B. (2013). Condition Assessment of Bridges: Past, Present, and Future. A Comple mentary Approach. Universidade Católica Editora.

- AASHTO — American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (2008). Bridging the Gap: Restoring and Rebuilding the Nation’s Bridges. July.

- Herrmann AW. ASCE 2013 report card for america's infrastructure. International Association for Bridge and Structural Engineering; 2013:9-10.

- Omar, T., & Nehdi, M. L. (2018). Condition assessment of reinforced concrete bridges: Current practice and research challenges. Infrastructures, 3(3), 36. [CrossRef]

- Abdelalim, A. M., Shalaby, Y., Ebrahim, G. A., & Badawy, M. (2024). An Article Review on Vision-Based Defect Detection Technologies for Reinforced Concrete Bridges. Ann Civ Eng Manag, 1(1), 01-17. [CrossRef]

- Transportation Officials. Subcommittee on Bridges. (2018). The manual for bridge evaluation. AASHTO.

- Kim, H., Ahn, E., Shin, M., & Sim, S. H. (2019). Crack and noncrack classification from concrete surface images using machine learning. Structural Health Monitoring, 18(3), 725-738. [CrossRef]

- Ali Mohamed, N., Mohammed Abdel-Alim, A., Hamdy Ghith, H., & Gamal Sherif, A. (2020). Assessment and Prediction Planning of RC Structures Using BIM Technology. Engineering Research Journal, 167, 394-403. [CrossRef]

- Abdelalim, A.M. and Said, S.O.M., 2021. “Dynamic labor tracking system in construction project using BIM technology”, International Journal of Civil and Structural Engineering Research ISSN 2348-7607 (Online), Vol. 9, Issue 1, pp: (10-20), Month: April 2021 - September 2021.

- Shawky, K. A., Abdelalim, A. M., & Sherif, A. G. (2024). Standardization of BIM Execution Plans (BEP’s) for Mega Construction Projects: A Comparative and Scientometric Study. [CrossRef]

- Shehab, A., & Abdelalim, A. M. Utilization BIM for Integrating Cost Estimation and Cost Control Using BIM in Construction Projects, 2023.

- Abdelalim, A. M., & Abo. elsaud, Y. (2019). Integrating BIM-based simulation technique for sustainable building design. In Project Management and BIM for Sustainable Modern Cities: Proceedings of the 2nd GeoMEast International Congress and Exhibition on Sustainable Civil Infrastructures, Egypt 2018–The Official International Congress of the Soil-Structure Interaction Group in Egypt (SSIGE) (pp. 209-238). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Abdelalim, A. M. (2019). A novel diagnostic prognostic approach for rehabilitated RC structures based on integrated probabilistic deterioration models. International Journal of Decision Sciences, Risk and Management, 8(3), 119-134. [CrossRef]

- Abdelalim, A.M., Nahla Ali Mohamed fahmy, Hatem Hamdy Ghith, Alaa Gamal sheriff (2020). Condition Assessment and Deterioration Prediction of RC Structures, International Journal of Civil and StructuralEngineering Research, 8(1), 173-181, available at: https://www.researchpublish.com/papers/condition-assessment-and-deterioration-prediction-of-rc-structures.

- Alsharqawi, M., Zayed, T., & Abu Dabous, S. (2020). Integrated condition-based rating model for sustainable bridgeManagement. Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities, 34(5), 04020091. [CrossRef]

- Rhee, J. Y., Park, K. E., Lee, K. H., & Kee, S. H. (2020). A practical approach to condition assessment of asphalt-covered concrete bridge decks on Korean expressways by dielectric constant measurements using air-coupled GPR. Sensors, 20(9), 2497. [CrossRef]

- Rogulj, K., Kilić Pamuković, J., & Jajac, N. (2021). Knowledge-based fuzzy expert system to the condition assessment of historic road bridges. Applied Sciences, 11(3), 1021. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y., Lei, X., Wang, P., & Sun, L. (2022). A data-driven approach for regional bridge condition assessment using inspection reports. Structural Control and Health Monitoring, 29(4), e2915. [CrossRef]

- Bertagnoli, G., Ferrara, M., Miceli, E., Castaldo, P., & Giordano, L. (2024). Safety assessment of an existing bridge deck subject to different damage scenarios through the global safety format ECOV. Engineering Structures, 306, 117859. [CrossRef]

- Shivam, S. (2024). Efficient Bridge Management System: A Comprehensive Approach for Sustainability of Bridge. Chemical Health Risks, JCHR (2024) 14(3), 1831-1845 (2251–6727).

- FHWA, N. (2012). Bridge inspector’s reference manual.

- Egyptian standard code for planning, designing, and constructing bridges and intersections (2015), No. (207/10).

- Abdelalim, A. M. (2010) ' Safety Assessment In The Rehabilitation Of RC Structures' Ain Shams University.

- Lin, S. S., Shen, S. L., Zhou, A., & Xu, Y. S. (2021). Risk assessment and management of excavation system based on fuzzy set theory and machine learning methods. Automation in Construction, 122, 103490.28. [CrossRef]

- Hachani, D., & Ounelli, H. (2008). Membership functions generation based on density function. Computational Intelligence and Security.

- Elbeltagi, E., Hosny, O. A., Elhakeem, A., Abd-Elrazek, M. E., & Abdullah, A. (2011). Selection of slab formwork system using fuzzy logic. Construction Management and Economics, 29(7), 659-670. [CrossRef]

- Bowman, M. D. (1988). The development of optimal strategies for maintenance, rehabilitation and replacement of highway bridges, Vol. 1: The elements of the Indiana bridge management system (IBMS). [CrossRef]

- Yeo, G. L., & Cornell, C. A. (2009). Building life-cycle cost analysis due to mainshock and aftershock occurrences. Structural safety, 31(5), 396-408.31. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Sinha, K. C., Saito, M., Murthy, S., Tee, A. B., & Bowman, M. D. (1990). The development of optimal strategies for maintenance, rehabilitation and replacement of highway bridges, Vol. 1: The elements of the Indiana bridge management system (IBMS).

- Elhakeem, A. A. (2005). An asset management framework for educational buildings with life-cycle cost analysis. Waterloo: University of Waterloo.

- Hu, J. Y., Zhang, S. S., Chen, E., & Li, W. G. (2022). A review on corrosion detection and protection of existing reinforced concrete (RC) structures. Construction and Building Materials, 325, 126718. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. (2003). Reinforcement corrosion in concrete structures, its monitoring and service life prediction––a review. Cement and concrete . composites, 25(4-5), 459-471. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C 1556 – 04 (2009) ASTM C 1556: Standard Test Method for Determining the Apparent Chloride Diffusion Coefficient of Cementitious Mixtures by Bulk Diffusion.

- Riding, K. A., Thomas, M. D., & Folliard, K. J. (2013). Apparent diffusivity model for concrete containing supplementary cementitious materials. ACI Materials Journal, 110(6), 705-714.

- Mangat, P. S., and Molloy, B. T., “Prediction of Long Term Chloride Concentrations in Concrete,” Materials and Structures, V. 27, 1994, pp. 338-346. [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, T. J., Weyers, R. E., Anderson-Cook, C. M., & Sprinkel, M. M. (2002). Probabilistic model for the chloride-induced corrosion service life of bridge decks. Cement and concrete research, 32(12), 1943-1960. [CrossRef]

- Weyers, R.E., Fitch, M.G., Larsen, E.P., Al-Quadi, I.L., Chamberlin, W.P., and Hoffman, P.C., 1993. Concrete Bridge Protection and Rehabilitation: Chemical Physical Techniques, Service Life Estimates, SHRP-S-668, Strategic Highway Research Program, National Research Council, Washington, D.C., 357 p.

- Weyers, R.E. 1998. “Service life model for concrete structures in chloride laden environments.” ACI Materials Journal, Vol. 95 (4), pp. 445-453.

- Ehlen, Mark A., Michael DA Thomas, and Evan C. Bentz. "Life-365 Service Life Prediction Model™ Version 2.2.3 " Concrete international 31, no. 5 (2020).

| Rating | Description |

|---|---|

| 10-N | Not applicable ( Just-Constructed) |

| 9 | Excellent Condition, new Condition, not worthy deficiency. |

| 8 | Very Good Condition, No repair is needed |

| 7 | Good Condition, Some minor Problems for Minor maintenance. |

| 6 | Satisfactory Condition, some minor deterioration for major maintenance. |

| 5 | Fair Condition, Minor Section Loss, Cracking or Scouring for minor Rehabilitation, Minor Rehabilitation is needed |

| 4 | Poor Condition, Advanced section loss, deterioration, Spalling or Scouring for major Rehabilitation, Major Rehabilitation is needed. |

| 3 | Serious Condition, Section Loss, Deterioration, Spalling or Scouring have seriously affected primary Structural components, Immediate Rehabilitation is needed. |

| 2 | Critical Condition, advanced deterioration of Primary Structural elements, Urgent Rehabilitation, the Structure may be closed until Corrective Actions taken. |

| 1 | Imminent Failure Condition, Major Deterioration or Section loss, Structure may be closed until Corrective actions which may put it back into light service. |

| 0 | Failed Condition, Beyond Corrective action, Out-of Service |

| Component | Weight | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Primary members | 15 |

| 2 | Deck | 12 |

| 3 | Abutment | 12 |

| 4 | Piers | 12 |

| 5 | Bearings | 9 |

| 6 | Bridge Seats | 9 |

| 7 | Wing walls | 7 |

| 8 | Back Wall | 7 |

| 9 | Secondary members | 6.5 |

| 10 | Joints | 4.5 |

| 11 | Wearing Surface | 4.5 |

| 12 | Sidewalks | 1 |

| 13 | Curb | 0.5 |

| Component | Weight | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Primary members | 10 |

| 2 | Deck | 8 |

| 3 | Abutment | 8 |

| 4 | Piers | 8 |

| 5 | Bearings | 6 |

| 6 | Bridge Seats | 6 |

| 7 | Wing walls | 5 |

| 8 | Back Wall | 5 |

| 9 | Secondary members | 5 |

| 10 | Joints | 4 |

| 11 | Wearing Surface | 4 |

| 12 | Sidewalks | 2 |

| 13 | Curb | 1 |

| Corrosion Degree | Steel Bars Condition |

|---|---|

| Condition-1 | Mill scale remains on the surface of steel bars, rust forms on the surface of reinforcing bars, but it is "thin" and the bar is "solid" throughout; rust is not formed on the surface of concrete. |

| Condition-2 | Small region covered by the "partly floating rust" and the rust is spotty too |

| Condition-3 | "Floating rust" is seen across the the entire circumstance or length of the reinforcement bars, although there is no observable loss of cross section area. |

| Condition-4 | "Loss of cross sectional area" is observed in reinforcing bars. |

| Corrosion Degree | Concrete Surface Condition | Subjective Assessment of Concrete Surface |

|---|---|---|

| Condition-1 | Unchanged | 6 |

| Condition-2 | Slight | 5 |

| Condition-3 | Obvious | 4 |

| Condition-4 | Deteriorated | 3 |

| pH value | f(x): Corrosion rate (mm/year) | Corrosion degree |

|---|---|---|

| 14 | 0.007214286 | Low |

| 13.6 | 0.022588235 | |

| 13.2 | 0.038893939 | |

| 12.8 | 0.05621875 | |

| 12.4 | 0.07466129 | |

| 12 | 0.094333333 | |

| 11.6 | 0.115362069 | Moderate |

| 11.2 | 0.137892857 | |

| 10.8 | 0.162092593 | |

| 10.4 | 0.188153846 | |

| 10 | 0.2163 | |

| 9.6 | 0.25 | Significant |

| 9.2 | 0.25 | |

| 8.8 | 0.25 | |

| 8.4 | 0.25 | |

| 8 | 0.25 | |

| 7.6 | 0.25 | |

| 7.2 | 0.25 | |

| 6.8 | 0.25 | |

| 6.4 | 0.25 | |

| 6 | 0.25 | |

| 5.6 | 0.25 | |

| 5.2 | 0.25 | |

| 4.8 | 0.25 | |

| 4.4 | 0.25 | |

| 4 | 0.25 | |

| 3.6 | 3.227719136 | Critical |

| 3.2 | 3.494957031 | |

| 2.8 | 3.854637755 | |

| 2.4 | 4.362368056 | |

| 2 | 5.12725 | |

| 1.6 | 6.392828125 | |

| 1.2 | 8.817472222 | |

| 0.8 | 14.8493125 | |

| 0.4 | 42.40525 |

| 6 | Satisfactory Condition |

| 5 | Fair Condition |

| 4 | Poor Condition |

| 3 | Serious Condition. |

| Rule no | Corrosion degree | Concrete surface condition | Semi-quantitative condition rating |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Low (L) | Unchanged (UC) | Satisfactory (ST) |

| 2 | Low (L) | Slight (SL) | Fair (F) |

| 3 | Low (L) | Obvious (O) | Poor (P) |

| 4 | Low (L) | Deteriorate (D) | Serious (S) |

| 5 | Moderate (M) | Unchanged (UC) | Satisfactory (ST) |

| 6 | Moderate (M) | Slight (SL) | Fair (F) |

| 7 | Moderate (M) | Obvious (O) | Poor (P) |

| 8 | Moderate (M) | Deteriorate (D) | Serious (S) |

| 9 | Significant (SI) | Unchanged (UC) | Fair (F) |

| 10 | Significant (SI) | Slight (SL) | Poor (P) |

| 11 | Significant (SI) | Obvious (O) | Poor (P) |

| 12 | Significant (SI) | Deteriorate (D) | Serious (S) |

| 13 | Critical ( C) | Unchanged (UC) | Poor (P) |

| 14 | Critical ( C) | Slight (SL) | Poor (P) |

| 15 | Critical ( C) | Obvious (O) | Serious (S) |

| 16 | Critical ( C) | Deteriorate (D) | Serious (S) |

| Corrosion Rate( mm/yr) | Semi Quantitative Condition Rating Score | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 3.87 | 3.35 | 3.41 | 3.35 | 3.35 |

| 0.45 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 3.87 | 3.35 | 3.41 | 3.35 | 3.35 |

| 0.4 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 3.87 | 3.35 | 3.41 | 3.35 | 3.35 |

| 0.35 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 3.87 | 3.35 | 3.41 | 3.35 | 3.35 |

| 0.3 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4 .5 | 4.5 | 4.01 | 3.87 | 3.86 | 3.87 | 3.41 | 3.41 |

| 0.25 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4.5 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 3.87 | 3.35 | 3.35 |

| 0.2 | 5.13 | 5.13 | 5.13 | 4.51 | 4.5 | 4.51 | 4.01 | 3.87 | 3.41 | 3.41 |

| 0.15 | 5.68 | 5.68 | 5.68 | 5.12 | 5 | 4.51 | 4.01 | 3.87 | 3.35 | 3.35 |

| 0.1 | 5.65 | 5.65 | 5.65 | 5.12 | 5 | 4.51 | 4.01 | 3.87 | 3.38 | 3.38 |

| 0.05 | 5.68 | 5.68 | 5.68 | 5.12 | 5 | 4.51 | 4.01 | 3.87 | 3.35 | 3.35 |

| Concrete Surface Condition | 7 | 6.5 | 6 | 5.5 | 5 | 4.5 | 4 | 3.5 | 3 | 2.5 |

| Corrosion Degree | Semi Quantitative Condition Rating Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3.87 | 3.32 | 3.38 | 3.32 |

| 0.28 | 4.4 | 4.44 | 4 | 3.87 | 3.8 | 3.85 | 3.36 |

| 0.23 | 5.03 | 4.54 | 4.29 | 4.33 | 4 | 3.87 | 3.36 |

| 0.18 | 5.67 | 5.13 | 5 | 4.5 | 4 | 3.87 | 3.33 |

| 0.13 | 5.61 | 5.11 | 5 | 4.5 | 4 | 3.89 | 3.39 |

| 0.08 | 5.62 | 5.12 | 5 | 4.5 | 4 | 3.88 | 3.38 |

| 0.03 | 5.67 | 5.13 | 5 | 4.5 | 4 | 3.87 | 3.33 |

| Concrete Surface Condition | 6 | 5.5 | 5 | 4.5 | 4 | 3.5 | 3 |

| Corrosion Degree | Semi Quantitative Condition Rating Score | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.48 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3.87 | 3.32 | 3.38 | 3.32 | 3.32 |

| 0.43 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3.87 | 3.32 | 3.38 | 3.32 | 3.32 |

| 0.38 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3.87 | 3.32 | 3.38 | 3.32 | 3.32 |

| 0.33 | 4.29 | 4.29 | 4.29 | 4.29 | 4 | 3.87 | 3.72 | 3.73 | 3.38 | 3.38 |

| 0.28 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4.5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3.87 | 3.35 | 3.35 |

| 0.23 | 5.02 | 5.02 | 5.02 | 4.52 | 4.21 | 4.26 | 4 | 3.87 | 3..34 | 3.34 |

| 0.18 | 5.31 | 5.31 | 5.31 | 4.82 | 4.73 | 4.5 | 4 | 3.87 | 3.35 | 3.35 |

| 0.13 | 5.66 | 5.66 | 5.66 | 5.13 | 5 | 4.5 | 4 | 3.87 | 3.34 | 3.34 |

| 0.08 | 5.68 | 5.68 | 5.68 | 5.13 | 5 | 4.5 | 4 | 3.87 | 3.37 | 3.37 |

| 0.03 | 5.68 | 5.68 | 5.68 | 5.13 | 5 | 4.5 | 4 | 3.87 | 3.32 | 3.32 |

| Concrete Surface Condition | 7 | 6.5 | 6 | 5.5 | 5 | 4.5 | 4 | 3.5 | 3 | 2.5 |

| Type of cement | C1 |

|---|---|

| Ordinary Portland cement ( type I ) | 1 |

| Ordinary Portland cement (type II) | 0.6 |

| Ferrous cement (ferrous slag 30% - 40%) | 1.4 |

| Ferrous cement (ferrous slag 60%) | 2.2 |

| Concrete atmospheric condition | C2 |

|---|---|

| wet concrete | 0.3 |

| Externally exposed concrete members | 0.5 |

| Internally exposed members. | 1 |

| Component No | Corrosion rate based on PH value (mm/yr) | Corrosion Degree | Concrete Surface Condition | Subjective assessment of concrete surface | Semi-quantitative condition Semi-quantitative condition | Average rate | Component rate* Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1L1 | 0.13 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4.5 | 54 |

| S6L1 | 0.08 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 5 | ||

| G1L1 | 0.065 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4.2 | 63 |

| G2L1 | 0.03 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ||

| G3L1 | 0.042 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 5 | ||

| G4L1 | 0.25 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ||

| G5L1 | 0.02 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ||

| AB1 | 0.01 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 48 |

| AB2 | 0.095 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ||

| W21 | 0.06 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4.5 | 31.5 |

| W22 | 0.042 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 5 | ||

| D1L1 | 0.25 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 60 |

| BCR 1 = 4.01 | |||||||

| Element | Predicted condition rating | CR*Wt |

|---|---|---|

| Deck Slabs | 4.84 | 58.08 |

| Girder | 4.85 | 72.75 |

| abutment | 4.89 | 58.68 |

| wing wall | 4.84 | 33.88 |

| Diaphragm | 4.63 | 69.45 |

| Overall BCR 2= 4.576 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).