Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

11 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

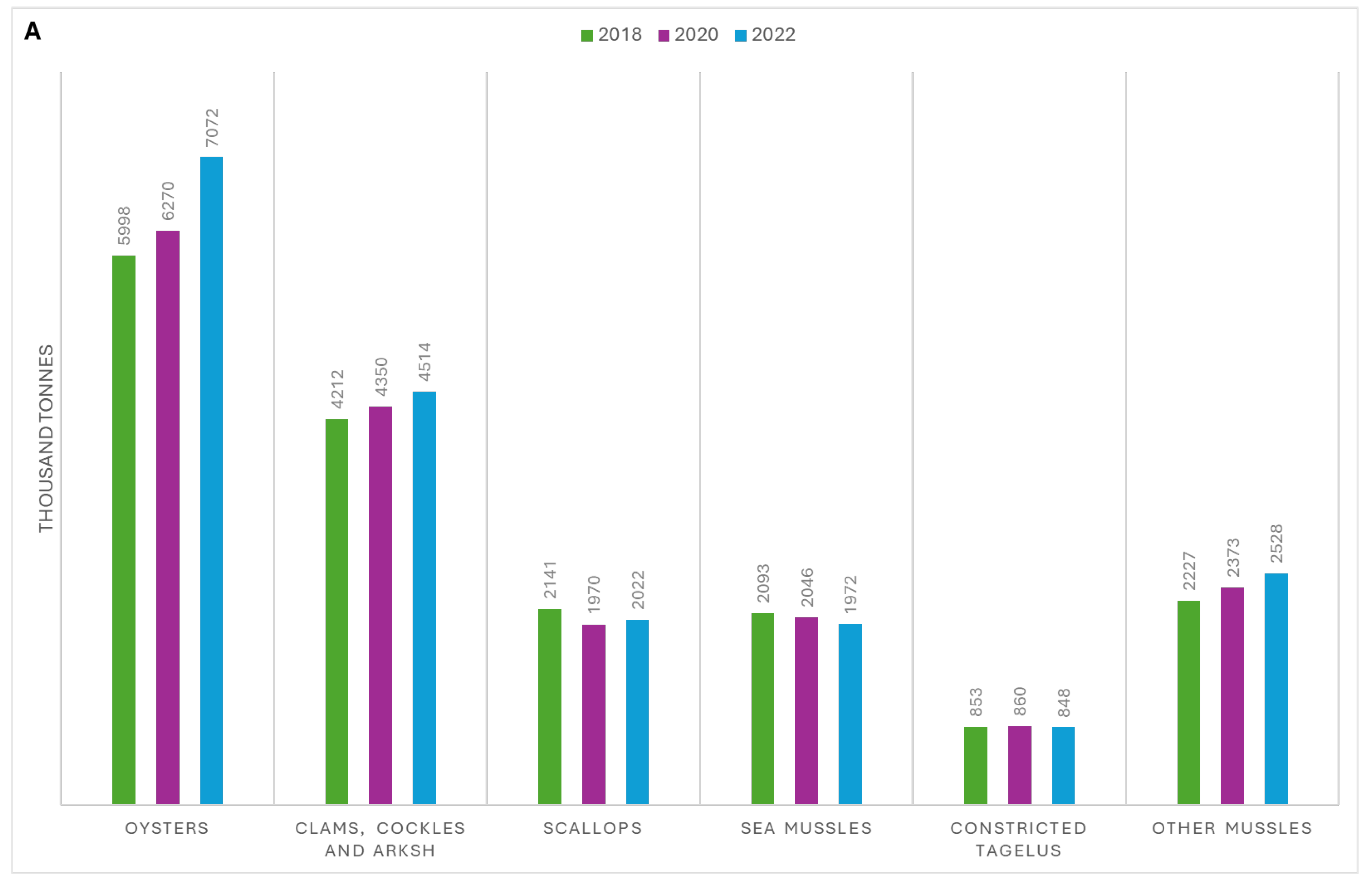

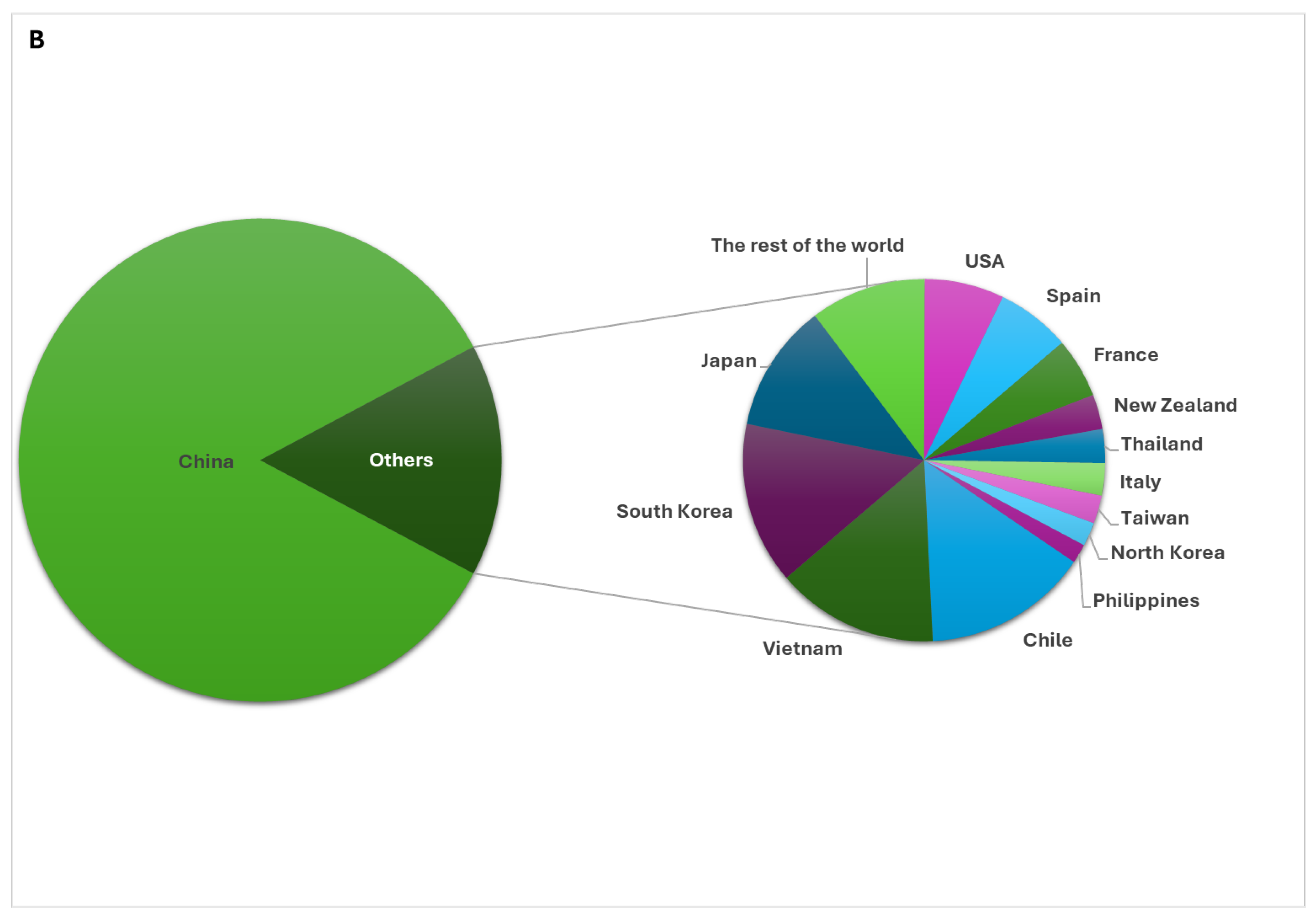

1. Introduction

2. Pathogens of High Biosecurity Concern in Global Mollusc Production and Their Current Molecular Diagnostic Methods

2.1. Viral Diseases Affecting Molluscs

2.1.1. Abalone Viral Ganglioneuritis (AVG)

2.1.2. Abalone Shrivelling Syndrome (AbSS)

2.1.3. Acute Viral Necrobiotic Disease

2.1.4. Infection with Ostreid Herpesvirus -1

2.2. Parasitic Diseases Affecting Molluscs

2.2.1. Haplosporidiosis

2.2.2. Bonamiosis

2.2.3. Marteiliosis

2.2.4. Marteilioides

2.2.5. Denman Island Disease

2.2.6. Perkinsosis

| Pathogen | Susceptible mollusc (s)# | Detection method |

|---|---|---|

| Virus | ||

| Abalone herpesvirus (AbHV) | Blacklip abalone1 Brown abalone2 Disc abalone2 Greenlip abalone1 Pink abalone2 Small abalone1 Tiger abalone1 |

cPCR [133] Sequencing [133] qPCR [29,30] ISH [25,134] |

| Abalone shrivelling syndrome (ASSV) | Disc abalone Small abalone |

qPCR [35] nPCR [34] |

| Acute Viral Necrobiotic Virus (AVNV | Scallops | cPCR [42] qPCR [42,135,136] |

| Ostreid herpesvirus-1 (OsHV-1) | Ark clams Australian flat oyster Bay scallops Blood clam Blue mussels Chilean oyster European clam Flat oyster Great scallop Hairy mussels Manila clam Pacific oyster Portuguese oyster Sydney cockle Sydney rock oysters Telline Virescent Oyster Whelks |

PCR [49] ISH [52,53] qPCR [54] |

| Parasite | ||

| Bonamiaspp. | Australian flat oyster3 Chilean oyster1 Crested oyster1 Dwarf oyster1 European flat oyster1 Hawaiian oyster1 Jinjiang oysters2 Olympia oyster Pacific oyster1 Portuguese oyster1 Suminoe oyster1 Sydney rock oysters |

cPCR [78,79] qPCR [80] mPCR [18] ISH [79,81] |

| Bonamia exitiosa | Argentinian flat oyster Australian flat oyster1 Chilean oyster1 Dwarf oyster1 Eastern oyster European flat oyster1 Olympia oyster Pacific oyster Sydney rock oyster |

qPCR [70] cPCR and sequencing [79,137,138] PCR-RFLP [73] mPCR [70] ISH [79,81,139] |

| Bonamia ostreae | Argentinian flat oyster3 Asiatic oyster Australian flat oyster Chilean oyster European flat oyster1 Pacific oyster3 Portuguese oyster Suminoe oyster1 |

ISH [79,108] qPCR [80,140,141] cPCR [78,79,142] mPCR [70] PCR-RFLP [73] |

| Haplosporidiumspp. | Australian flat oyster Blue mussel California mussel Cockles Eastern oyster European flat oyster Fresh water snails |

qPCR [143,144] cPCR [61,145,146] mPCR [63] ISH [61] |

| Haplosporidium nelson | Eastern oyster Pacific oyster |

ISH [147] cPCR [148] qPCR [149] mPCR [63] |

| Marteiliaspp. | Argentinian flat oyster3 Australian flat oyster Banded Carpet Shell Blacklip oyster Blacklip pearl oyster Blue mussel Calico scallop Chilean oyster Common cockle Dwarf oyster Eastern oyster European flat oyster Grooved razor clam Hooded oyster Iwagaki oyster Jackknife clam Manila clam Maxima clam Mediterranean mussel Northern horse mussel Pacific oyster Palourde clam Peppery furrow shell Pod razor Puelchean Oyster Pullet carpet shell Rock oyster Striped venus clam Suminoe oyster Venerid clam |

cPCR [90,91,94] ISH [94] RFLP-PCR [150] |

|

Marteilia refringens |

Argentinian flat oyster2 Asiatic oyster1 Australian flat oyster2 Banded Carpet Shell Blue mussela1 Calico scallop2 Chilean oyster oyster1 Common cockle1 Dwarf oyster2 Eastern oyster1 European flat oyster1 Grooved razor clam1 Hooded oyster1 Jackknife clam Mediterranean mussel1 Olympia oyster1 Pacific oyster2 Palourde clam Planktonic copepods2 Pod razor Pullet carpet shell Small brown mussel2 Striped venus clam1 |

nPCR [91,151] cPCR and sequencing [90,94,98] mPCR [18] qPCR [152] ISH [90,91,100,153] |

| Marteilia sydneyi | Flat oyster Sydney rock oyster |

cPCR [154] mPCR [18] ISH [155] |

| Marteilioidesspp. | Manila Clam Northern blacklip oyster Pacific oyster Suminoe Oyster |

nPCR [156] |

|

Marteilioides chungmuensis |

Iwagaki oyster Manila clam Pacific Oyster Pacific oyster Suminoe Oyster |

cPCR [103,157] ISH [103] |

| Mikrocytos mackini | Eastern oyster European flat oyster Olympia flat oyster Pacific oyster |

cPCR [158] qPCR [109] ISH [159] FISH [158] |

| Perkinsusspp. | Asian littleneck clam Baltic clam Eastern oyster European flat oyster Hong Kong oyster Mangrove oyster Manila Clam Palourde clam Soft shell clam Stout tagelus Suminoe Oyster Sydney cockle1 Yesso scallop |

cPCR [124,160] ISH [126] PCR—DGGE1 [161] mPCR-ELISA [131] |

| Perkinsusandrewsi | Baltic Clam | cPCR [129] |

| Perkinsusatlanticus | Palourde clam | cPCR [162] mPCR-ELISA [131] |

| Perkinsosis marinus | Baltic macoma Blue mussel Cortez oyster1 Eastern oyster1 Mangrove oyster1 Pacific oyster1 Soft shelled clam Suminoe oyster1 |

cPCR [125,160] ISH# [126,128,163] qPCR [122,125] mPCR-ELISA [131] RFLP-PCR [164] |

| Perkinsosis olseni | Akoya pearl oyster1 Asian littleneck clam1 Australian flat oyster1 Blacklip abalone1 Blacklip pearl oyster1 Crocus clam1 European aurora venus clam1 Giant clam1 Greenlip abalone1 Green-lipped mussel1 Japanese pearl oyster1 Kumamoto oyster Manila clam1 Maxima clam1 New Zealand ark shell1 New Zealand cockle1 New Zealand pauaa1 New Zealand pipia1 New Zealand scallop1 Pacific oyster1 Pearl oyster1 Pullet carpet shell1 Sand cockle Silverlip pearl oyster1 Staircase abalone1 Suminoe oyster1 Sydney cockle1 Venerid clam1 Venerid commercial clam Venus clam Wedge shell Whirling abalone1 |

ISH [126,163,165] cPCR [125,163] qPCR [125] |

3. Isothermal Nucleic Acid Detection Methods

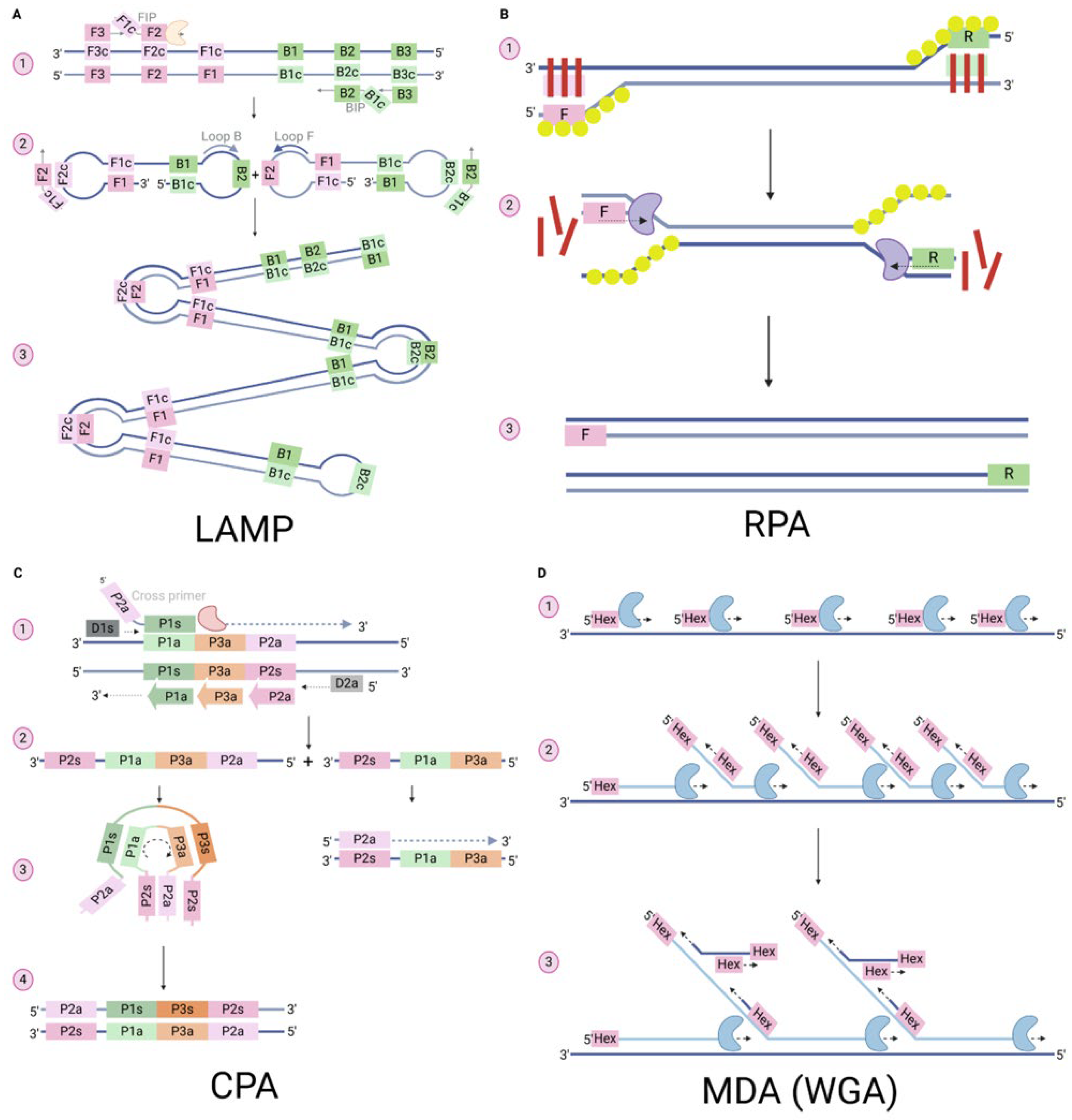

3.1. Loop Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP)

3.2. Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA)

3.3. Cross-Priming Isothermal Amplification (CPA)

3.4. Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA)

4. Application of Isothermal Amplification of Viral Pathogens Infecting Molluscs

5. Application of Isothermal Amplification of Parasitic Pathogens Infecting Molluscs

| Pathogen | Type | Target | Sample | Duration (minutes) |

Sensitivity# | In-field | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus | |||||||

| Abalone herpesvirus (AVG) | LAMP | DNA polymerase gene | Nerve tissues | 60 | 100 copies/µL | No | [176] |

| Abalone herpesvirus (AVG) | RPA | ORF38 | Muscle tissue | 20 | 100 copies | No | [170] |

| Acute Viral Necrobiotic Virus (AVNV) | LAMP | - | Tissues | 60 | 1 fg | No | [199] |

| Abalone shrivelling syndrome associated virus (AbSV) | LAMP | ORF2 | Water | 60 | 10 copies | No | [200] |

| OsHV-1 | LAMP | ORF 109 | Tissues except for gonad and adductor muscle | 60 | 20 copies | No | [201] |

| OsHV-1 | LAMP | ORF 4 | Tissues | 60 | 103 copies | No | [202] |

| OsHV-1 | RPA | ORF 95 | Tissues | 20 | 207 copies | No | [204] |

| OsHV-1 | RPA | ORF 95 | Tissues | 20 | 5 copies | No | [203] |

| OsHV-1- SB* | CPA | - | - | 60 | 30 copies /µL | No | [171] |

| Parasites | |||||||

| B. exitiosa | MDA-WGA | Actin | Gill tissues | 90 | - | No | [19] |

| B. exitiosa | LAMP | Actin | Gill tissues | 30 | 50 copies/µL | No | [206] |

| B. ostreae | LAMP | Actin-1 | Gill tissues | 30 | 50 copies/µL | No | [206] |

| Bonamia spp. | LAMP | 18S | Gill tissues | 30 | 50 copies/µL | No | [206] |

| Marteilia refringens | LAMP | - | 60 | 20 fg | No | [207] | |

| Perkinsus spp. | LAMP | Internal Transcribed spacer 2 (ITS-2) | Gills/ body tissues | 49.8 |

10 copies of plasmid DNA |

No | [177] |

| Perkinsus spp. | LAMP | ITS2 | Tissues | 30-60 | 3.6-36 ng | No | [208] |

| Perkinsus beihaiensis | RPA | ITS | Gills | 25 | 26 copies | No | [209] |

| Perkinsus olseni | LAMP | ITS 5.8S rDNA | - | 60 | 30 copies | No | [210] |

| Perkinsus olseni | LAMP | Between 5.8S and ITS 2 | - | - | 100 fg | No | [172] |

6. Future Improvements in Application of Isothermal Amplification

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Worldometer. [cited 2024 04/10/2022]; Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/.

- Carnegie, R.B., I. Arzul, and D. Bushek, Managing marine mollusc diseases in the context of regional and international commerce: policy issues and emerging concerns. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B, 2016. 371(1689): p. 20150215. [CrossRef]

- FAO, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2018-Meeting the sustainable development goals, in Fisheries and Aquaculture Department, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. 2020.

- FAO, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024. Blue Transformation in action, in The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (SOFIA). 2024, FAO ;: Rome, Italy ;.

- Benkendorff, K., Molluscan biological and chemical diversity: Secondary metabolites and medicinal resources produced by marine molluscs. Biol. Rev, 2010. 85(4): p. 757-775. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S., S. Singh, and B. Pal, Superior adsorption removal of dye and high catalytic activity for transesterification reaction displayed by crystalline CaO nanocubes extracted from mollusc shells. FPT, 2021. 213: p. 106707. [CrossRef]

- Marín Aguilera, B., F. Iacono, and M. Gleba, Colouring the mediterranean: Production and consumption of purple-dyed textiles in pre-roman times. J. Mediterr. Archaeol., 2019. [CrossRef]

- Meng, X., et al., Mannan oligosaccharide increases the growth performance, immunity and resistance capability against Vibro Parahemolyticus in juvenile abalone Haliotis discus hannai Ino. Fish Shellfish Immunol., 2019. 94: p. 654-660. [CrossRef]

- Arzul, I., et al., Viruses infecting marine molluscs. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2017. 147: p. 118-135. [CrossRef]

- Renault, T. and B. Novoa, Viruses infecting bivalve molluscs. Aquat. Living Resour., 2004. 17(4): p. 397-409. [CrossRef]

- Paillard, C., F. Le Roux, and J.J. Borrego, Bacterial disease in marine bivalves, a review of recent studies: trends and evolution. Aquat. Living Resour., 2004. 17(4): p. 477-498. [CrossRef]

- Berthe, F.C., et al., Marteiliosis in molluscs: a review. Aquat. Living Resour., 2004. 17(4): p. 433-448. [CrossRef]

- Villalba, A., et al., Perkinsosis in molluscs: a review. Aquat. Living Resour., 2004. 17(4): p. 411-432. [CrossRef]

- Gleason, F.H., et al., The roles of endolithic fungi in bioerosion and disease in marine ecosystems. I. General concepts. Mycology, 2017. 8(3): p. 205-215. [CrossRef]

- OIE. Notifiable Animal Diseases. [cited 2023 22nd November]; Available from: https://www.woah.org/en/what-we-do/animal-health-and-welfare/animal-diseases/?_tax_animal=aquatics%2Cmolluscs.

- Arzul, I., T. Renault, and C. Lipart, Experimental herpes-like viral infections in marine bivalves: demonstration of interspecies transmission. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2001. 46(1): p. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Arzul, I., et al., Evidence for interspecies transmission of oyster herpesvirus in marine bivalves. J. Gen. Virol., 2001. 82(4): p. 865-870. [CrossRef]

- Canier, L., et al., A new multiplex real-time PCR assay to improve the diagnosis of shellfish regulated parasites of the genus Marteilia and Bonamia. Prev. Vet. Med., 2020. 183: p. 105126. [CrossRef]

- Prado Alvarez, M., et al., Whole-genome amplification: a useful approach to characterize new genes in unculturable protozoan parasites such as Bonamia exitiosa. Parasitol., 2015. 142(12): p. 1523-1534. [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.M., et al., Susceptibility of two abalone species, Haliotis diversicolor supertexta and Haliotis discus hannai, to Haliotid herpesvirus 1 infection. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2019. 160: p. 26-32. [CrossRef]

- Corbeil, S., Abalone Viral Ganglioneuritis. Pathogens, 2020. 9(9): p. 720. [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.-W., et al., Exploring the chronic mortality affecting abalones in taiwan: differentiation of abalone herpesvirus-associated acute infection from chronic mortality by pcr and in situ hybridization and histopathology. Taiwan Vet. J., 2016. 42(01): p. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Mouton, A., An Epidemiological Study of Parasites Infecting The South African Abalone (Haliotis Midae) In Western Cape Aquaculture Facilities. 2011, University of Pretoria (South Africa).

- Pen Heng, C., et al., Herpes-like virus infection causing mortality of cultured abalone Haliotis diversicolor supertexta in Taiwan. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2005. 65(1): p. 23-27. [CrossRef]

- Corbeil, S., et al., Abalone viral ganglioneuritis: Establishment and use of an experimental immersion challenge system for the study of abalone herpes virus infections in Australian abalone. Virus Res., 2012. 165(2): p. 207-213. [CrossRef]

- Corbeil, S., et al., Innate resistance of New Zealand paua to abalone viral ganglioneuritis. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2017. 146: p. 31-35. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., et al., Virus infection in cultured abalone, Haliotis diversicolor Reeve in Guangdong Province, China. J. Shellfish Res., 2004. 23(4): p. 1163-1169.

- Hooper, C., P. Hardy-Smith, and J. Handlinger, Ganglioneuritis causing high mortalities in farmed Australian abalone (Haliotis laevigata and Haliotis rubra). Aust. Vet. J., 2007. 85(5): p. 188-193. [CrossRef]

- Caraguel, C.G., et al., Diagnostic test accuracy when screening for Haliotid herpesvirus 1 (AbHV) in apparently healthy populations of Australian abalone Haliotis spp. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2019. 136(2): p. 199-207. [CrossRef]

- Corbeil, S., et al., Development and validation of a TaqMan® PCR assay for the Australian abalone herpes-like virus. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2010. 92(1): p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-H., et al., Evaluation of a bacteriophage-related chimeric marine virus associated with abalone mortality in Taiwan. Taiwan Vet. J., 2014. 40(02): p. 77-82. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Spring explosive epidemic disease of abalone in Dongshan district. Xiamen Univ. Nat. Sci., 1999. 38: p. 644-654.

- Handlinger, J., General pathology and diseases of abalone, in Aquaculture Pathophysiology, F.S.B. Kibenge, B. Baldisserotto, and R.S.-M. Chong, Editors. 2022, Academic Press. p. 405-447.

- Jiang, J.-Z., et al., Nested PCR detection of abalone shriveling syndrome-associated virus in China. J. Virol. Methods, 2012. 184(1-2): p. 21-26. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.Z., et al., Quantitative PCR detection for abalone shriveling syndrome-associated virus. J. Virol. Methods, 2012. 184(1): p. 15-20. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J., et al., A bacteriophage-related chimeric marine virus infecting abalone. PloS one, 2010. 5(11): p. e13850. [CrossRef]

- Yang, R., Molecular epidemiological investigation on abalone shriveling syndrome-associated virus and herpes-like virus and its related research. 2013, ShangHai, China: ShangHai Ocean University.

- Haixin, A., et al., Artificial infection of cultured scallop Chlamys farreri by pathogen from acute virus necrobiotic disease. JFSC, 2003. 10(5): p. 386-391.

- Tang, B., et al., Physiological and immune responses of zhikong scallop Chlamys farreri to the acute viral necrobiotic virus infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol., 2010. 29(1): p. 42-48. [CrossRef]

- Ai, H., et al., Artificial infection of cultured scallop Chlamys farreri by pathogen from acute virus necrobiotic disease. Zhongguo shui chan ke xue = Journal of fishery sciences of China, 2003. 10(5): p. 386-391.

- Chen, G., et al., A preliminary study of differentially expressed genes of the scallop Chlamys farreri against acute viral necrobiotic virus (AVNV). Fish Shellfish Immunol., 2013. 34(6): p. 1619-1627. [CrossRef]

- Ren, W., Detection methods, sequence of the complete genome of acute viral necrobiotic virus isolated from scallop Chlamys farreri. 2009, Ocean University China.

- Chongming, W., et al., Purification and ultrastructure of a spherical virus in cultured scallop Chlamys farreri. Shuichan xuebao, 2002. 26(2): p. 180-183.

- Fu, C., W. Song, and Y. Li, Monoclonal antibodies developed for detection of an epizootic virus associated with mass mortalities of cultured scallop Chlamys farreri. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2005. 65(1): p. 17-22. [CrossRef]

- Yun, L., et al., Detection of Acute Virus Necrobiotic Disease Virus (AVND Virus) in Chlamys farreri Using ELISA Technique. Gaojishu Tongxun, 2003. 13(7): p. 90-92.

- Fuhrmann, M., et al., Ostreid herpesvirus disease, in Aquaculture Pathophysiology, F.S.B. Kibenge, B. Baldisserotto, and R.S.-M. Chong, Editors. 2022, Academic Press. p. 473-488.

- Burge, C.A., et al., The first detection of a novel OsHV-1 microvariant in San Diego, California, USA. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2021. 184: p. 107636. [CrossRef]

- Roque, A., et al., First report of OsHV-1 microvar in Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) cultured in Spain. Aquac., 2012. 324-325: p. 303-306. [CrossRef]

- Renault, T. and C. Lipart. Diagnosis of herpes-like virus infections in oysters using molecular techniques. in Aquaculture and water: fish culture, shellfish culture and water usage. 1998.

- Schikorski, D., et al., Experimental infection of Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas spat by ostreid herpesvirus 1: demonstration of oyster spat susceptibility. Vet. Res., 2011. 42: p. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Arzul, I., et al., Detection of oyster herpesvirus DNA and proteins in asymptomatic Crassostrea gigas adults. Virus Res., 2002. 84(1-2): p. 151-160. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa Solomieu, V., et al., Diagnosis of Ostreid herpesvirus 1 in fixed paraffin-embedded archival samples using PCR and in situ hybridisation. J. Virol. Methods, 2004. 119(2): p. 65-72. [CrossRef]

- Lipart, C. and T. Renault, Herpes-like virus detection in infected Crassostrea gigas spat using DIG-labelled probes. J. Virol. Methods, 2002. 101(1-2): p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Pepin, J.F., A. Riou, and T. Renault, Rapid and sensitive detection of ostreid herpesvirus 1 in oyster samples by real-time PCR. J. Virol. Methods, 2008. 149(2): p. 269-276. [CrossRef]

- Burreson, E.M. and S.E. Ford, A review of recent information on the Haplosporidia, with special reference to Haplosporidium nelsoni (MSX disease). Aquat. Living Resour., 2004. 17(4): p. 499-517. [CrossRef]

- Comps, M. and Y. Pichot, Fine spore structure of a haplosporidan parasitizing Crassostrea gigas: taxonomic implications. Dis. Aquat. Org, 1991. 11: p. 73-77.

- Andrews, J.D. Oyster mortality studies in Virginia IV. MSX in James River public seed beds. in Proceedings of the National Shellfisheries Association. 1964.

- Ford, S.E. and H.H. Haskin, History and epizootiology of Haplosporidium nelsoni (MSX), an oyster pathogen in Delaware Bay, 1957–1980. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 1982. 40(1): p. 118-141. [CrossRef]

- Ford, S.E., et al., Investigating the life cycle of Haplosporidium nelsoni (MSX): A review. J. Shellfish Res., 2018. 37(4): p. 679-693. [CrossRef]

- Barber, B.J., S.E. Ford, and D. Littlewood, A physiological comparison of resistant and susceptible oysters Crassostrea virginica (Gmelin) exposed to the endoparasite Haplosporidium nelsoni (Haskin, Stauber & Mackin). J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol., 1991. 146(1): p. 101-112. [CrossRef]

- Stokes, N.A. and E.M. Burreson, Differential diagnosis of mixed Haplosporidium costale and Haplosporidium nelsoni infections in the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, using DNA probes. J. Shellfish Res., 2001. 20(1): p. 207.

- Arzul, I. and R.B. Carnegie, New perspective on the haplosporidian parasites of molluscs. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2015. 131: p. 32-42. [CrossRef]

- Penna, M.S., M. Khan, and R.A. French, Development of a multiplex PCR for the detection of Haplosporidium nelsoni, Haplosporidium costale andPerkinsus marinus in the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica, Gmelin, 1971). MCP, 2001. 15(6): p. 385-390. [CrossRef]

- Carnegie, R.B., et al., Bonamia perspora n. sp.(Haplosporidia), a parasite of the oyster Ostreola equestris, is the first Bonamia species known to produce spores. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol., 2006. 53(4): p. 232-245. [CrossRef]

- Dinamani, P., M. Hine, and J. Jones, Occurrence and characteristics of the haemocyte parasite Bonamia ostreae in the New Zealand dredge oyster Tiostrea lutaria. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 1987. 3: p. 37-44.

- Culloty, S.C. and M.F. Mulcahy, Bonamia ostreae in the native oyster Ostrea edulis. Fish. Bull. Mar. Inst. Dublin, 2007.

- European Commission, D.-G.f.H.a.F.S., Commission implementing regulations (EU) 2018/1882 in Official Journal of the European Union. 2022.

- Bower, S.M., S.E. McGladdery, and I.M. Price, Synopsis of infectious diseases and parasites of commercially exploited shellfish. Annu. Rev. Fish Dis., 1994. 4: p. 1-199. [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, L.v.G., et al., A non-lethal method for detection of Bonamia ostreae in flat oyster (Ostrea edulis) using environmental DNA. Sci. Rep., 2020. 10(1): p. 16143. [CrossRef]

- Ramilo, A., et al., Species-specific diagnostic assays for Bonamia ostreae and B. exitiosa in European flat oyster Ostrea edulis: conventional, real-time and multiplex PCR. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2013. 104(2): p. 149-161. [CrossRef]

- Pichot, Y., et al., Recherches sur Bonamia ostreae gen. n., sp. n., parasite nouveau de l'huître plate Ostrea edulis L. Rev. Trav. Off. Pech. Marit., 1979. 43(1): p. 131-140.

- Van Banning, P., The life cycle of the oyster pathogen Bonamia ostreae with a presumptive phase in the ovarian tissue of the European flat oyster, Ostrea edulis. Aquac., 1990. 84(2): p. 189-192. [CrossRef]

- Abollo, E., et al., First detection of the protozoan parasite Bonamia exitiosa (Haplosporidia) infecting flat oyster Ostrea edulis grown in European waters. Aquaculture, 2008. 274(2): p. 201-207. [CrossRef]

- Lane, H.S., Studies on Bonamia parasites (Haplosporidia) in the New Zealand flat oyster Ostrea chilensis. 2018, University of Otago.

- Hine, P., et al., Ultrastructure of Mikrocytos mackini, the cause of Denman Island disease in oysters Crassostrea spp. and Ostrea spp. in British Columbia, Canada. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2001. 45(3): p. 215-227. [CrossRef]

- Culloty, S.C., M.A. Cronin, and M.F. Mulcahy, Potential resistance of a number of populations of the oyster Ostrea edulis to the parasite Bonamia ostreae. Aquac., 2004. 237(1): p. 41-58. [CrossRef]

- Van Banning, P., Observations on bonamiasis in the stock of the European flat oyster, Ostrea edulis, in the Netherlands, with special reference to the recent developments in Lake Grevelingen. Aquac., 1991. 93(3): p. 205-211. [CrossRef]

- Carnegie, R.B., et al., Development of a PCR assay for detection of the oyster pathogen Bonamia ostreae and support for its inclusion in the Haplosporidia. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2000. 42(3): p. 199-206. [CrossRef]

- Cochennec, N., et al., Detection of Bonamia ostreae Based on Small Subunit Ribosomal Probe. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2000. 76(1): p. 26-32. [CrossRef]

- Corbeil, S., et al., Development of a TaqMan PCR assay for the detection of Bonamia species. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2006. 71(1): p. 75-80. [CrossRef]

- Hill, K.M., et al., Observation of a Bonamia sp. infecting the oyster Ostrea stentina in Tunisia, and a consideration of its phylogenetic affinities. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2010. 103(3): p. 179-185. [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, N., et al., Bonamia exitiosa (Haplosporidia) observed infecting the European flat oyster Ostrea edulis cultured on the Spanish Mediterranean coast. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2012. 110(3): p. 307-313. [CrossRef]

- Hine, P., Severe apicomplexan infection in the oyster Ostrea chilensis: a possible predisposing factor in bonamiosis. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2002. 51(1): p. 49-60. [CrossRef]

- Calvo, L.M.R., G.W. Calvo, and E.M. Burreson, Dual disease resistance in a selectively bred eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, strain tested in Chesapeake Bay. Aquac., 2003. 220(1-4): p. 69-87. [CrossRef]

- Comps, M., Marteilia lengehi n. sp., parasite de l'huître Crassostrea cucullata Born. Rev. Trav. Off. Pech. Marit., 1976. 40(2): p. 347-349.

- Perkins, F.O. and P.H. Wolf, Fine structure of Marteilia sydneyi sp. n.: haplosporidan pathogen of Australian oysters. J. Parasitol., 1976: p. 528-538. [CrossRef]

- Villalba, A., et al., Cockle Cerastoderma edule fishery collapse in the Ría de Arousa (Galicia, NW Spain) associated with the protistan parasite Marteilia cochillia. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2014. 109(1): p. 55-80. [CrossRef]

- Norton, J., F. Perkins, and E. Ledua, Marteilia-like infection in a giant clam, Tridacna maxima, in Fiji. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 1993. [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, N., T. Green, and N. Itoh, Marteilia spp. parasites in bivalves: A revision of recent studies. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2015. 131: p. 43-57. [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, F., et al., DNA probes as potential tools for the detection of Marteilia refringens. Mar. Biotechnol., 1999. 1(6): p. 588-597. [CrossRef]

- Lopez Flores, I., et al., The molecular diagnosis of Marteilia refringens and differentiation between Marteilia strains infecting oysters and mussels based on the rDNA IGS sequence. Parasitol., 2004. 129(4): p. 411-419. [CrossRef]

- Birch, G., C. Apostolatos, and S. Taylor, A remarkable recovery in the Sydney rock oyster (Saccostrea glomerata) population in a highly urbanised estuary (Sydney estuary, Australia). J. Coast. Res., 2013. 29(5): p. 1009-1015. [CrossRef]

- Grizel, H., Etude des récentes épizooties de l'huître plate Ostrea edulis Linné et de leur impact sur l'ostréiculture bretonne. 1985, Universite des sciences et techniques du Languedoc.

- Le Roux, F., et al., Molecular evidence for the existence of two species of Marteilia in Europe. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol., 2001. 48(4): p. 449-454. [CrossRef]

- Audemard, C., et al., Needle in a haystack: involvement of the copepod Paracartia grani in the life-cycle of the oyster pathogen Marteilia refringens. Parasitol., 2002. 124(3): p. 315-323. [CrossRef]

- Villalba, A., et al., Marteiliasis affecting cultured mussels Mytilus galloprovincialis of Galicia (NW Spain). I. Etiology, phases of the infection, and temporal and spatial variability in prevalence. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 1993. [CrossRef]

- Wetchateng, T., et al., Withering syndrome in the abalone Haliotis diversicolor supertexta. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2010. 90(1): p. 69-76. [CrossRef]

- Grizel, H., et al., Recherche sur l'agent de la maladie de la glande digestive de Ostrea edulis Linné. Sci. Pech. , 1974(240): p. 7-30.

- Grizel, H., et al., Etude d'un parasite de la glande digestive observé au cours de l'épizootie actuelle de l'huître plate. C. R. Acad. Sci., 1974. 279: p. 783-785.

- Thébault, A., et al., Validation of in situ hybridisation and histology assays for the detection of the oyster parasite Marteilia refringens. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2005. 65(1): p. 9-16. [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.K., Preliminary studies on the sporozoan parasites in oysters on the southern coast of Korea. Bull. Korean Fish. Soc., 1972. 5: p. 76-82.

- Comps, M. and I. Desportes, Etude ultrastructurale des Marteilioides chungmuensis NG, N. SP. parasite des ovocytes de l'huître Crassostrea gigas Th. Protist., 1986. 22(3): p. 279-285.

- Itoh, N., et al., DNA probes for detection of Marteilioides chungmuensis from the ovary of Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Fish Pathol., 2003. 38(4): p. 163-169. [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T.T., F.C. Berthe, and K.-S. Choi, Prevalence and infection intensity of the ovarian parasite Marteilioides chungmuensis during an annual reproductive cycle of the oyster Crassostrea gigas. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2003. 56(3): p. 259-267. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T. and R. Lester, Sporulation of Marteilioides branchialis n. sp.(Paramyxea) in the Sydney rock oyster, Saccostrea commercialis: an electron microscope study. The Journal of protozoology, 1992. 39(4): p. 502-508. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J., et al., A study of diagnostic methods for Marteilioides chungmuensis infections in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. "J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2012. 111(1): p. 27-32. [CrossRef]

- Burki, F., et al., Phylogenomics of the Intracellular Parasite Mikrocytos mackini Reveals Evidence for a Mitosome in Rhizaria. Curr. Biol., 2013. 23(16): p. 1541-1547. [CrossRef]

- Carnegie, R.B., B.J. Barber, and D.L. Distel, Detection of the oyster parasite Bonamia ostreae by fluorescent in situ hybridization. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2003. 55(3): p. 247-252. [CrossRef]

- Polinski, M., et al., Molecular detection of Mikrocytos mackini in Pacific oysters using quantitative PCR. Mol Biochem Parasitol., 2015. 200(1-2): p. 19-24. [CrossRef]

- Auzoux-Bordenave, S., et al., In vitro sporulation of the clam pathogen Perkinsus atlanticus (Apicomplexa, Perkinsea) under various environmental conditions. Oceanogr. Lit. Rev., 1996. 9(43): p. 926.

- Dantas Neto, M.P., et al., First record of Perkinsus chesapeaki infecting Crassostrea rhizophorae in South America. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2016. 141: p. 53-56. [CrossRef]

- Park, K.I. and K.S. Choi, Application of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for studying of reproduction in the Manila clam Ruditapes philippinarum (Mollusca: Bivalvia): I. Quantifying eggs. Aquac., 2004. 241(1-4): p. 667-687. [CrossRef]

- Park, K.-I., et al., Pathology survey of the short-neck clam Ruditapes philippinarum occurring on sandy tidal flats along the coast of Ariake Bay, Kyushu, Japan. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2008. 99(2): p. 212-219. [CrossRef]

- Neto, M.P.D., et al., First record of Perkinsus chesapeaki infecting Crassostrea rhizophorae in South America. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2016. 141: p. 53-56. [CrossRef]

- Hanrio, E., et al., Immunoassays and diagnostic antibodies for Perkinsus spp. pathogens of marine molluscs. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2021. 147: p. 13-23. [CrossRef]

- Dungan, C.F. and K.S. Reece, 5.2. 1 Perkinsus spp. Infections of Marine Molluscs (2020). AFS-FHS, 2020.

- Valencia, J., et al., New data on Perkinsus mediterraneus in the Balearic Archipelago: locations and affected species. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2014. 112(1): p. 69-82. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.D., Epizootiology of the disease caused by the oyster pathogen Perkinsus marinus and its effects on the oyster industry. American Fisheries Society, 1988. 18.

- Cook, T., et al., The Relationship Between Increasing Sea-surface Temperature and the Northward Spread ofPerkinsus marinus (Dermo) Disease Epizootics in Oysters. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci., 1998. 46(4): p. 587-597. [CrossRef]

- Pires, D., et al., Histopathologic Lesions in Bivalve Mollusks Found in Portugal: Etiology and Risk Factors. J. mar. sci. eng., 2022. 10(2): p. 133. [CrossRef]

- Casas, S.M., A. Villalba, and K.S. Reece, Study of perkinsosis in the carpet shell clam Tapes decussatus in Galicia (NW Spain). I. Identification of the aetiological agent and in vitro modulation of zoosporulation by temperature and salinity. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2002. 50(1): p. 51-65. [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, J., C. Miller, and A.E. Wilbur, TaqMan® MGB real-time PCR approach to quantification of Perkinsus marinus and Perkinsus spp. in oysters. J. Shellfish Res., 2006. 25(2): p. 619-624. [CrossRef]

- Lenaers, G., et al., Dinoflagellates in evolution. A molecular phylogenetic analysis of large subunit ribosomal RNA. J. Mol. Evol., 1989. 29(1): p. 40-51. [CrossRef]

- Moss, J.A., et al., Description of Perkinsus beihaiensis n. sp., a new Perkinsus sp. parasite in oysters of southern China. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol., 2008. 55(2): p. 117-130. [CrossRef]

- Audemard, C., K.S. Reece, and E.M. Burreson, Real-time PCR for detection and quantification of the protistan parasite Perkinsus marinus in environmental waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 2004. 70(11): p. 6611-6618. [CrossRef]

- Elston, R.A., et al., Perkiasus sp infection risk for manila clams, Venerupis philippinarum (A. Adams and Reeve, 1850) on the Pacific coast of North and Central America. J. Shellfish Res., 2004. 23(1): p. 101.

- Ramilo, A., et al., Update of information on perkinsosis in NW Mediterranean coast: Identification of Perkinsus spp.(Protista) in new locations and hosts. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2015. 125: p. 37-41. [CrossRef]

- Reece, K.S., C.F. Dungan, and E.M. Burreson, Molecular epizootiology of Perkinsus marinus and P. chesapeaki infections among wild oysters and clams in Chesapeake Bay, USA. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2008. 82(3): p. 237-248. [CrossRef]

- COSS, C.A., et al., Description of Perkinsus andrewsi n. sp. isolated from the Baltic clam (Macoma balthica) by characterization of the ribosomal RNA locus, and development of a species-specific PCR-based diagnostic assay. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol., 2001. 48(1): p. 52-61. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.-S., et al., Survey on Perkinsus species in Manila clam Ruditapes philippinarum in Korean waters using species-specific PCR. Fish Pathol., 2017. 52(4): p. 202-205. [CrossRef]

- Elandalloussi, L.M., et al., Development of a PCR-ELISA assay for diagnosis of Perkinsus marinus and Perkinsus atlanticus infections in bivalve molluscs. MCP, 2004. 18(2): p. 89-96. [CrossRef]

- Moss, J.A., Characterization of exotic pathogens associated with the suminoe oyster, Crassostrea ariakensis. 2007.

- Chen, M.H., et al., Development of a polymerase chain reaction for the detection of abalone herpesvirus infection based on the DNA polymerase gene. J. Virol. Methods, 2012. 185(1): p. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Fegan, M., et al. Development of an in situ hybridisation assay for the detection and identification of the abalone herpes-like virus. in 4th FRDC Aquatic Animal Health Subprogram Scientific Conference, Cairns. 2009.

- Ren, W., et al., Development and application of a FQ-PCR assay for detection of Chlamys farreri acute viral necrobiotic virus. JFSC, 2009. 16(4): p. 564-571.

- Xing, J., T. Lin, and W. Zhan, Variations of enzyme activities in the haemocytes of scallop Chlamys farreri after infection with the acute virus necrobiotic virus (AVNV). Fish Shellfish Immunol., 2008. 25(6): p. 847-852. [CrossRef]

- Narcisi, V., et al., Detection of Bonamia ostreae and B. exitiosa (Haplosporidia) in Ostrea edulis from the Adriatic Sea (Italy). Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2010. 89(1): p. 79-85. [CrossRef]

- Carnegie, R.B. and N. Cochennec-Laureau, Microcell parasites of oysters: recent insights and future trends. Aquat. Living Resour., 2004. 17(4): p. 519-528. [CrossRef]

- Ramilo, A., A. Villalba, and E. Abollo, Species-specific oligonucleotide probe for detection of Bonamia exitiosa (Haplosporidia) using in situ hybridisation assay. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2014. 110(1-2): p. 81-91. [CrossRef]

- Marty, G.D., et al., Histopathology and a real-time PCR assay for detection of Bonamia ostreae in Ostrea edulis cultured in western Canada. Aquac., 2006. 261(1): p. 33-42. [CrossRef]

- Robert, M., et al., Molecular detection and quantification of the protozoan Bonamia ostreae in the flat oyster, Ostrea edulis. MCP, 2009. 23(6): p. 264-271. [CrossRef]

- Engelsma, M.Y., et al., Epidemiology of Bonamia ostreae infecting european flat oysters ostrea edulis from Lake Grevelingen, The Netherlands. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 2010. 409: p. 131-142. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z., et al., A duplex quantitative real-time PCR assay for the detection of Haplosporidium and Perkinsus species in shellfish. Parasitol. Res., 2013. 112(4): p. 1597-1606. [CrossRef]

- Arzul, I., et al., First characterization of the parasite Haplosporidium costale in France and development of a real-time PCR assay for its rapid detection in the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Transbound. Emerg. Dis., 2022. 69(5): p. e2041-e2058. [CrossRef]

- Lopez Nuñez, R., et al., Detection of Haplosporidium pinnae from Pinna nobilis Faeces. J. mar. sci. eng., 2022. 10(2): p. 276. [CrossRef]

- Carella, F., et al., In the wake of the ongoing mass mortality events: Co-occurrence of Mycobacterium, Haplosporidium and other pathogens in Pinna nobilis collected in Italy and Spain (Mediterranean Sea). Front. mar. sci., 2020. 7: p. 48. [CrossRef]

- Stokes, N.A., Burreson, Eugene M., A sensitive and specific DNA probe for the oyster pathogen Haplosporidium nelsoni. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol., 1995. 42(4): p. 350-357. [CrossRef]

- Stokes, N.A., M.E. Siddall, and E.M. Burreson, Detection of Haplosporidium nelsoni (Haplosporidia: Haplosporidiidae) in oysters by PCR amplification. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 1995. 23(2): p. 145-152. [CrossRef]

- Day, J.M., D.E. Franklin, and B.L. Brown, Use of Competitive PCR to Detect and Quantify Haplosporidium nelsoni Infection (MSX disease) in the Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica). Mar Biotechnol (NY), 2000. 2(5): p. 456-465. [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, N., et al., Molecular characterization of the Marteilia parasite infecting the common edible cockle Cerastoderma edule in the Spanish Mediterranean coast: a new Marteilia species affecting bivalves in Europe? Aquac., 2012. 324: p. 20-26. [CrossRef]

- Pernas, M., et al., Molecular methods for the diagnosis of Marteilia refringens. B EUR ASSOC FISH PAT., 2001. 21(5): p. 200-208.

- Carrasco, N., et al., Application of a competitive real time PCR for detection of Marteilia refringens genotype “O” and “M” in two geographical locations: The Ebro Delta, Spain and the Rhine-Meuse Delta, the Netherlands. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2017. 149: p. 51-55. [CrossRef]

- Berthe, F., et al., The existence of the phylum Paramyxea Desportes and Perkins, 1990 is validated by the phylogenetic analysis of the Marteilia refringens small subunit ribosomal RNA. J. Euk. Microbiol, 2000. 47: p. 288-293.

- Anderson, T., R. Adlard, and R. Lester, Molecular diagnosis of Marteilia sydneyi (Paramyxea) in Sydney rock oysters, Saccostrea commercialis (Angas). Journal of Fish Diseases, 1995. 18(6): p. 507-510. [CrossRef]

- Kleeman, S., et al., Specificity of PCR and in situ hybridization assays designed for detection of Marteilia sydneyi and M. refringens. Parasitology, 2002. 125(2): p. 131-141. [CrossRef]

- Yanin, L., et al., Molecular and histological identification of Marteilioides infection in Suminoe Oyster Crassostrea ariakensis, Manila Clam Ruditapes philippinarum and Pacific Oyster Crassostrea gigas on the south coast of Korea. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2013. 114(3): p. 277-284. [CrossRef]

- Itoh, N., et al., An ovarian infection in the Iwagaki oyster, Crassostrea nippona, with the protozoan parasite Marteilioides chungmuensis. J. Fish Dis., 2004. 27(5): p. 311-314.

- Carnegie, R.B., et al., Molecular detection of the oyster parasite Mikrocytos mackini, and a preliminary phylogenetic analysis. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2003. 54(3): p. 219-227. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, G.R., S.M. Bower, and R.B. Carnegie, Sensitivity of a digoxigenin-labelled DNA probe in detecting Mikrocytos mackini, causative agent of Denman Island disease (mikrocytosis), in oysters. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2005. 88(2): p. 89-94. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, A.G., J.D. Gauthier, and G.R. Vasta, A semiquantitative PCR assay for assessing Perkinsus marinus infections in the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica. J. Parasitol., 1995: p. 577-583.

- Ramilo, A., et al., Perkinsus olseni and P. chesapeaki detected in a survey of perkinsosis of various clam species in Galicia (NW Spain) using PCR–DGGE as a screening tool. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2016. 133: p. 50-58. [CrossRef]

- De la Herrán, R., et al., Molecular characterization of the ribosomal RNA gene region of Perkinsus atlanticus: its use in phylogenetic analysis and as a target for a molecular diagnosis. Parasitol., 2000. 120(4): p. 345-353. [CrossRef]

- Moss, J.A., E.M. Burreson, and K.S. Reece, Advanced Perkinsus marinus infections in Crassostrea ariakensis maintained under laboratory conditions. J. Shellfish Res., 2006. 25(1): p. 65-72. [CrossRef]

- Abollo, E., et al., Differential diagnosis of Perkinsus species by polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism assay. Molecular and Cellular Probes, 2006. 20(6): p. 323-329. [CrossRef]

- Reece, K.S., et al., A novel monoclonal Perkinsus chesapeaki in vitro isolate from an Australian cockle, Anadara trapezia. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2017. 148: p. 86-93. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J., et al., Mass mortality in Korean bay scallop (Argopecten irradians) associated with Ostreid Herpesvirus-1 μVar. Transbound. Emerg. Dis., 2019. 66(4): p. 1442-1448. [CrossRef]

- Roque, A., et al., Detection and identification of tdh-and trh-positive Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains from four species of cultured bivalve molluscs on the Spanish Mediterranean Coast. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 2009. 75(23): p. 7574-7577. [CrossRef]

- Schikorski, D., et al., Development of TaqMan real-time PCR assays for monitoring Vibrio harveyi infection and a plasmid harbored by virulent strains in European abalone Haliotis tuberculata aquaculture. Aquac., 2013. 392-395: p. 106-112. [CrossRef]

- Piepenburg, O., et al., DNA detection using recombination proteins. PLoS Biol., 2006. 4(7): p. e204. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F., et al., Real-time isothermal detection of Abalone herpes-like virus and red-spotted grouper nervous necrosis virus using recombinase polymerase amplification. J. Virol. Methods, 2018. 251: p. 92-98. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., et al., Establishment and application of a cross priming isothermal amplification technique for detection of SB strain of Ostreid herpesvirus-1. J. Fish. China. , 2015. 39(4): p. 580-588.

- Pang, Y., et al., Establishment and application of visual LAMP assay on Perkinsus olseni. Southwest China Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 2012. 25(1): p. 302-305.

- Notomi, T., et al., Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic acids res. , 2000. 28(12): p. e63-e63. [CrossRef]

- Fakruddin, M., Loop mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP)–an alternative to polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Bangladesh Res. Publ. J, 2011. 5(4).

- Tao, Y., et al., High-performance detection of Mycobacterium bovis in milk using digital LAMP. Food chem., 2020. 327: p. 126945. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.H., et al., The development of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for rapid and sensitive detection of abalone herpesvirus DNA. J. Virol. Methods, 2014. 196: p. 199-203. [CrossRef]

- Feng, C., et al., Development of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification method for detection of Perkinsus spp. in mollusks. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2013. 104(2): p. 141-148. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., et al., Development of a real-time loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay and visual LAMP assay for detection of African swine fever virus (ASFV). J. Virol. Methods, 2020. 276: p. 113775. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, G. and M. Sakai, Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assays for detection and identification of aquaculture pathogens: current state and perspectives. AMBB, 2014. 98(7): p. 2881-2895. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J. and X. Zhao, Isothermal Amplification Technologies for the Detection of Foodborne Pathogens. Food Anal. Methods, 2018. 11(6): p. 1543-1560. [CrossRef]

- Daher, R.K., et al., Recombinase Polymerase Amplification for Diagnostic Applications. Clin. Chem., 2016. 62(7): p. 947-958. [CrossRef]

- Lobato, I.M. and C.K. O'Sullivan, Recombinase polymerase amplification: Basics, applications and recent advances. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem., 2018. 98: p. 19-35. [CrossRef]

- Dai, T., et al., Comparative evaluation of a novel recombinase polymerase amplification-lateral flow dipstick (RPA-LFD) assay, LAMP, conventional PCR, and leaf-disc baiting methods for detection of Phytophthora sojae. Front. microbiol., 2019. 10: p. 1884. [CrossRef]

- TwistDx. TwistDx. [cited 2024 02/09]; Available from: https://www.twistdx.co.uk/rpa/.

- Xu, G., et al., Cross priming amplification: mechanism and optimization for isothermal DNA amplification. Sci Rep, 2012. 2: p. 246. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y., Isothermal amplification-based methods for assessment of microbiological safety and authenticity of meat and meat products. Food Control, 2021. 121: p. 107679. [CrossRef]

- Fang, R., et al., Cross-Priming Amplification for Rapid Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Sputum Specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol., 2009. 47(3): p. 845-847. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z., et al., Isothermal cross-priming amplification implementation study. Lett. Appl. Microbiol, 2015. 60(3): p. 205-209. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z., et al., Rapid Detection of Food-Borne Escherichia coli O157:H7 with Visual Inspection by Crossing Priming Amplification (CPA). Food Anal. Methods, 2020. 13(2): p. 474-481. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al., Rapid and sensitive detection of Listeria monocytogenes by cross-priming amplification of lmo0733 gene. FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 2014. 361(1): p. 43-51. [CrossRef]

- Long, N., et al., Recent advances and application in whole-genome multiple displacement amplification. Quant. Biol., 2020. 8(4): p. 279-294. [CrossRef]

- Dean, F.B., et al., Comprehensive human genome amplification using multiple displacement amplification. PNAS, 2002. 99(8): p. 5261-5266. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S., et al., The use of whole genome amplification in the study of human disease. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol., 2005. 88(1): p. 173-189. [CrossRef]

- Konakandla, B., Y. Park, and D. Margolies, Whole genome amplification of Chelex-extracted DNA from a single mite: a method for studying genetics of the predatory mite Phytoseiulus persimilis. Exp. Appl. Acarol., 2006. 40(3): p. 241-247. [CrossRef]

- Lepere, C., et al., Whole-genome amplification (WGA) of marine photosynthetic eukaryote populations. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 2011. 76(3): p. 513-523. [CrossRef]

- Sabina, J. and J.H. Leamon, Bias in whole genome amplification: causes and considerations. WGA, 2015: p. 15-41. [CrossRef]

- Berthet, N., et al., Phi29 polymerase based random amplification of viral RNA as an alternative to random RT-PCR. BMC Mol. Biol., 2008. 9(1): p. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., et al., Single-Cell Whole-Genome Amplification and Sequencing: Methodology and Applications. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet., 2015. 16(1): p. 79-102. [CrossRef]

- Ren, W., C. Wang, and Y. Cai, Loop-mediated isothermal amplification for rapid detection of acute viral necrobiotic virus in scallop Chlamys farreri. Acta Virol., 2009. 53(3): p. 161-167. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J., et al., Detection of abalone shrivelling syndrome-associated virus using loop-mediated isothermal amplification. J Fish Dis, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ren, W., et al., Development of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for rapid and sensitive detection of ostreid herpesvirus 1 DNA. J. Virol. Methods, 2010. 170(1-2): p. 30-36. [CrossRef]

- Zaczek Moczydłowska, M.A., et al., A single-tube HNB-based loop-mediated isothermal amplification for the robust detection of the Ostreid herpesvirus 1. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2020. 21(18): p. 6605. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F., et al., Real-time quantitative isothermal detection of Ostreid herpesvirus-1 DNA in Scapharca subcrenata using recombinase polymerase amplification. J. Virol. Methods, 2018. 255: p. 71-75. [CrossRef]

- Toldrà, A., et al., Detection of isothermally amplified ostreid herpesvirus 1 DNA in Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) using a miniaturised electrochemical biosensor. Talanta, 2020. 207: p. 120308. [CrossRef]

- Xia, J., et al., Complete genome sequence of Ostreid herpesvirus-1 associated with mortalities of Scapharca broughtonii broodstocks. Virol J, 2015. 12: p. 110. [CrossRef]

- Cano, I., et al., Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification for the Fast Detection of Bonamia ostreae and Bonamia exitiosa in Flat Oysters. Pathogens, 2024. 13(2): p. 132. [CrossRef]

- Xie, L., et al., Development of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for visual detection of Marteilia refringens in shellfish. Chin. J. Vet. Sci., 2012. 32(7): p. 993-996.

- Mendoza Avilés, I., et al., Loop-mediated isothermal amplification for diagnosing marine pathogens in tissues of Crassostrea spp. and white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, farmed in Mexico. Cienc. Mar., 2021. 47(4): p. 227–239-227–239. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L., et al., Utilization of recombinase polymerase amplification combined with a lateral flow strip for detection of Perkinsus beihaiensis in the oyster Crassostrea hongkongensis. Parasit. Vectors., 2019. 12(1): p. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Qu, P., et al., Establishment and application of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) method for Perkinsus olseni detection. J. Fish. China. , 2012. 36(8): p. 1281-1289.

- Bass, D., et al., Diverse Applications of Environmental DNA Methods in Parasitology. Trends Parasitol., 2015. 31(10): p. 499-513. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, C.S., et al., Validation of a quantitative PCR assay for detection and quantification of ‘Candidatus Xenohaliotis californiensis’. Dis. Aquat. Organ., 2014. 108(3): p. 251-259. [CrossRef]

- Vincent-Hubert, F., et al., Adsorption of norovirus and ostreid herpesvirus type 1 to polymer membranes for the development of passive samplers. J. Appl. Microbiol., 2017. 122(4): p. 1039-1047. [CrossRef]

- Toldrà, A., et al., Rapid capture and detection of ostreid herpesvirus-1 from Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas and seawater using magnetic beads. PLoS One, 2018. 13(10): p. e0205207. [CrossRef]

- Morga, B., et al., Haemocytes from Crassostrea gigas and OsHV-1: A promising in vitro system to study host/virus interactions. J. Invertebr. Pathol., 2017. 150: p. 45-53. [CrossRef]

- Sakudo, A. and T. Onodera, Virus capture using anionic polymer-coated magnetic beads. "Int. J. Mol. Med., 2012. 30(1): p. 3-7. [CrossRef]

- Sakudo, A., et al., Capture of dengue virus type 3 using anionic polymer-coated magnetic beads. Int. J. Mol. Med., 2011. 28(4): p. 625-628. [CrossRef]

- Chomczynski, P. and M. Rymaszewski, Alkaline polyethylene glycol-based method for direct PCR from bacteria, eukaryotic tissue samples, and whole blood. Biotechniques, 2006. 40(4): p. 454-458. [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakopoulou, M.-E., et al., Boiling extraction method vs commercial kits for bacterial DNA isolation from food samples. J. Food Nutr. Res., 2020. 3(4): p. 311-319.

- Barreda García, S., et al., Helicase-dependent isothermal amplification: a novel tool in the development of molecular-based analytical systems for rapid pathogen detection. Anal. Bioanal. Chem., 2018. 410(3): p. 679-693. [CrossRef]

- Nagamine, K., T. Hase, and T. Notomi, Accelerated reaction by loop-mediated isothermal amplification using loop primers. MCP, 2002. 16(3): p. 223-229. [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.t., et al., Betaine-assisted recombinase polymerase assay for rapid hepatitis B virus detection. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem., 2021. 68(3): p. 469-475. [CrossRef]

- Pasookhush, P., et al., Development of duplex loop-mediated isothermal amplification (dLAMP) combined with lateral flow dipstick (LFD) for the rapid and specific detection of Vibrio vulnificus and V. parahaemolyticus. N. Am. J. Aquac., 2016. 78(4): p. 327-336. [CrossRef]

- Surasilp, T., et al., Rapid and sensitive detection of Vibrio vulnificus by loop-mediated isothermal amplification combined with lateral flow dipstick targeted to rpoS gene. MCP, 2011. 25(4): p. 158-163. [CrossRef]

- Chu, F.L. and R. Hale, Relationship between pollution and susceptibility to infectious disease in the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica. Mar. Environ. Res., 1994. 38(4): p. 243-256. [CrossRef]

- Renault, T., Viruses infecting marine mollusks Studies in viral ecol., 2021: p. 275-303.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).