1. Introduction

Prion diseases, also referred to as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSE), occupy a unique position among neurodegenerative conditions due to their infectious nature and the central role played by misfolded scrapie prion protein (PrP

Sc) [

1,

2]. According to the “protein-only” hypothesis, prion pathogenesis arises when the normally soluble cellular prion protein (PrP

C) adopts a pathogenic β-sheet-rich conformation (PrP

Sc) capable of templating the misfolding of additional PrP

C molecules [

1]. This self-propagating mechanism has profoundly influenced how researchers conceive of other protein misfolding disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and bovine spongiform encephalopathy, all of which appear to share pathological features such as aberrant protein conformers and progressive neuronal degeneration [

3,

4]. Despite these conceptual advances, significant gaps persist in our understanding of precisely how prion-like mechanisms intersect with inflammatory processes, particularly those driven by bacterial components, during the onset and progression of brain neurodegeneration.

Emerging evidence suggests that bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a key molecule from the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, might contribute to or exacerbate prion-like processes. In vitro studies have demonstrated that LPS can induce the formation of protease-resistant recombinant prion protein (moPrP

Res) [

5,

6], raising intriguing possibilities about the ability of bacterial factors to modulate pathological protein folding in vivo. Moreover, chronic peripheral administration of LPS has been shown to exacerbate the pathophysiology of other neurodegenerative proteinopathies, including Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. In these conditions, LPS activates the immune system [

12,

13], leading to microglial overactivation and sustained neuroinflammation within the central nervous system (CNS), key processes that further promote neuronal damage [

14,

15,

16]. Indeed, prolonged peripheral exposure to LPS can compromise the blood–brain barrier, alter cytokine networks, and potentiate protein misfolding, thereby driving or exacerbating neurodegenerative pathology [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Traditionally, experimental models of scrapie rely on intracerebral inoculation because it yields relatively short incubation periods. However, to better mimic natural prion transmission, alternative peripheral routes, such as subcutaneous injection, have also been used, even though they typically require longer incubation times [

12,

21]. Importantly, subcutaneous administration has been shown to be equally effective for disease transmission in various animal models and may provide a more physiologically relevant approximation of how prions disseminate from peripheral tissues to the CNS [

12,

21].

Whether LPS alone, or in combination with a prion-like substrate, can trigger or accelerate prion-like neurodegeneration in healthy animals remains unclear. Addressing this gap is crucial because it could resolve whether misfolded prion protein isoforms indeed require additional factors such as LPS to exert their full pathogenic effects in vivo, or whether prion-like neurodegeneration can be wholly attributed to misfolded protein conformers. A clearer delineation of these processes is particularly important given the rapidly expanding recognition that many neurodegenerative syndromes likely exist on a spectrum of protein misfolding and inflammatory pathologies, rather than being wholly distinct entities.

Thus, in this study, we aimed to determine whether LPS-converted recombinant prion protein (moPrPRes), generated entirely in vitro by incubation with Escherichia coli 0111:B4 LPS, without traditional amplification methods such as seeding or serial protein misfolding cyclic amplification (sPMCA), could independently induce prion-like neurodegeneration in wild-type mice following subcutaneous administration. Additionally, we sought to assess whether chronic peripheral exposure to bacterial LPS, in the absence of classical prion agents, might trigger spongiform brain pathology and associated neurodegenerative changes. Finally, we investigated the synergistic effects of co-administering LPS with a classical scrapie strain (Rocky Mountain Laboratory, RML) and moPrPRes, focusing on its impact on disease progression, neuropathological severity, and prion protein deposition. By exploring these mechanisms, our study aims to investigate the complex interactions between inflammatory triggers and prion-like processes, shedding light on how these interactions may contribute to the early stages of prion and other protein-misfolding neurodegenerative disorders.

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

7. Materials and Methods

7.1. Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in compliance with ethical standards and received approval from the University of Alberta Animal Care and Use Committee for Health Sciences Laboratory Animal Services. The procedures adhered to the guidelines established by the Canadian Council on Animal Care [

22]. All aspects of animal care and use conformed to the University of Alberta's animal welfare laws, guidelines, and policies, ensuring that the welfare of the experimental animals was prioritized throughout the research.

7.2. Experimental Design and Animals

A total of ninety wild-type female FVB/N mice, sourced from Charles River Laboratories in Wilmington, USA, were utilized for this study. These mice were five weeks old at the start of the experiment and were randomly assigned to one of six treatment groups, each comprising fifteen mice. The treatment groups included: saline (negative control), LPS derived from Escherichia coli 0111:B4, moPrPRes (29-232) generated by incubation with E. coli 0111:B4 LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA), moPrPRes combined with LPS, RML (Rocky Mountain Laboratory) + LPS, and RML (positive control).

For the administration of treatments, bacterial LPS and saline were delivered subcutaneously using ALZET® osmotic mini pumps (ALZET, Cupertino, CA). These pumps were surgically implanted on the backs of the mice, allowing for continuous infusion at a rate of 0.11 µL/h over a period of six weeks. The dosage of bacterial LPS was set at 0.1 µg per gram of body weight. Concurrently, a single subcutaneous injection of either moPrP

Res (29-232) at a dosage of 45 µg per mouse or RML, containing 107 ID50 units of scrapie prions, was administered at the time of pump implantation, according to the designated treatment group. The recombinant mouse prion protein (29-232) was provided by Dr. David Wishart’s laboratory at the University of Alberta and was injected in a total volume of 200 µL per mouse. For further details regarding the experimental design, readers can refer to the work by Hailemariam et al. [

6].

7.3. Weight Measurement

To monitor the health and development of the mice throughout the study, body weight measurements were taken for each individual mouse in all treatment groups. This monitoring commenced at six weeks of age, immediately following the initiation of treatment. Weight measurements were conducted monthly to assess the overall health status of the mice. As the experiment progressed and mortality rates increased, the remaining mice from each treatment group were weighed again at 102 and 110 weeks of age, providing valuable data on the long-term effects of the treatments administered.

7.4. Mouse Recombinant Prion Protein

Lyophilized lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) was reconstituted with Milli-Q ddH₂O to achieve an initial working concentration of 5 mg/mL. This stock solution was then used to reconstitute lyophilized mouse recombinant prion protein (moPrP, 29-232) to approximately 0.5 mg/mL, resulting in a weight ratio of moPrP:LPS of 1:1 when mixed. Given that the average molecular weight of LPS is approximately 10 kDa, which is roughly half that of the prion protein, this weight ratio corresponds to a molar ratio of approximately 2:1. Due to the absence of a definitive molecular weight for LPS, weight (mg) ratios were utilized in this study to maintain consistency and facilitate comparison.

The prion conversion reactions were monitored using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, performed in the far-UV region (190-260 nm) at 25 ºC in a 0.02 cm path-length quartz cell using an Olis DSM 17 spectropolarimeter. Five scans were averaged for each CD spectrum collected, with protein concentrations maintained at 0.5 mg/mL (25 µM). Reference spectra were acquired under the same conditions and were subtracted from the measured prion spectra prior to calculating molar ellipticity. Molar ellipticity values were determined using an average amino acid molecular weight of 113.64 g/mol. Additionally, the secondary structure content was analyzed with CDPro, employing the CONTINLL algorithm and the SP22X reference set. The endpoint for β-sheet conversion was defined when the helical content (as measured by CD) dropped to 15% and the β-sheet content exceeded 25%. The endpoint for fibril propagation was established when the helical content fell to 10% and the β-sheet content surpassed 30%.

To facilitate conversion, lyophilized moPrP was reconstituted to 0.5 mg/mL with the previously prepared LPS solution. Following this, LPS was removed from the LPS-converted prion solution using polymyxin B agarose resin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). Five hundred µL of the resin was added to a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube and equilibrated with three separate volumes of 500 µL ammonium bicarbonate buffer (100 mM, pH 8.0; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). Subsequently, 250 µL of the PrP sample was added and incubated at room temperature for 60 minutes, allowing any unbound LPS to attach to the resin. The resin was then pelleted by centrifugation at 850 g for 5 minutes, and the supernatant was discarded. This washing procedure was repeated three additional times, with the supernatant applied to freshly equilibrated resin. The final supernatant was analyzed using the Pyrochrome Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Associates of Cape Cod Inc., East Falmouth, MA) to quantify any residual LPS contamination, while the secondary structure of the moPrPres was confirmed by CD spectroscopy.

7.5. Euthanasia

The euthanasia of the animals was conducted at two critical time points: 11 weeks post-infection (wpi) and at the terminal stage of the disease. Five mice from each treatment group were euthanized at 11 wpi, all exhibiting normal body weights and showing no clinical signs of prion disease or any abnormalities. The remaining ten mice per treatment group were euthanized at the terminal stage, characterized by clinical signs including kyphosis, ataxia, dysmetria, tremors, head tilt, tail rigidity, bradykinesia, proprioceptive deficits, stupor, loss of deep pain sensation, and significant weight loss.

7.6. Tissue Preparation

Prior to euthanasia, mice were anesthetized using isoflurane gas. Reflexes were assessed to ensure loss of pain sensation before proceeding with euthanasia through cardiac puncture to draw all blood. Following euthanasia, brain samples were collected immediately and sectioned in a sagittal orientation. The samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA), using a fixation volume ten times greater than that of the tissue for a minimum of 48 hours at room temperature. After fixation, brain samples were rinsed with tap water for 20 minutes and subsequently placed in 15 mL tubes containing 70% ethanol (Commercial Alcohol, Winnipeg, Canada). The fixed brain samples were stored at 4 ºC until further processing for immunohistochemical (IHC) staining.

The samples underwent a series of IHC stainings to evaluate the pattern and distribution of PrPSc and amyloid plaque (Ap) deposition across various regions of the brain, along with assessments of astrogliosis and spongiform vacuolation.

7.7. Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining

Brain tissue samples were processed following the methodology described by Chishti et al. [

23]. All brain tissues were mounted on adhesive-treated slides and embedded in paraffin (Formula “R” paraffin, Surgipath®, Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Germany), then dried overnight at 37 ºC. The paraffin-embedded tissues were deparaffinized and rehydrated using a graded series of ethanol and deionized water. Slides were then incubated in filtered Mayer’s Hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) and subsequently in eosin Y. After drying, images of each slide were captured using a digital slide scanner (NanoZoomer XR, Hamamatsu, SZK, Japan).

7.8. PrPSc Staining

Brain samples were processed for PrP

Sc staining following the protocol outlined by Bell et al. [

24]. The procedure aimed to achieve maximum clearance of PrP

C from the tissues. A series of incubations were performed using the following reagents: formic acid, 4 M guanidine thiocyanate, and 3% hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2). Afterward, the samples were treated with a mouse monoclonal SAF83 antibody (1:500 dilution; Cayman Chemical, Michigan, USA), followed by incubation with streptavidin-peroxidase. The development of the staining was facilitated by the addition of diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate, and the slides were counterstained with Mayer’s Hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) to enhance visualization.

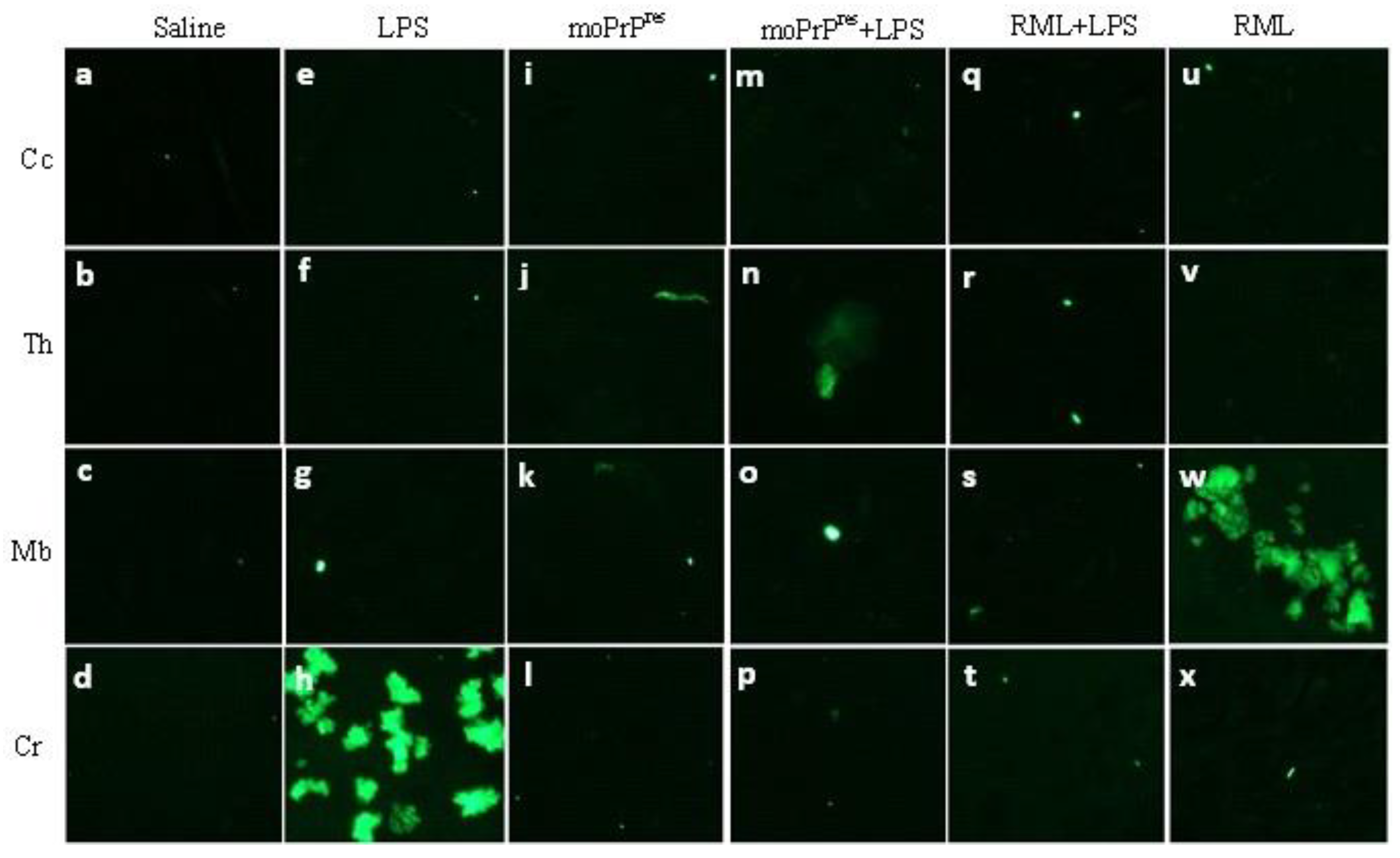

7.9. Amyloid Plaque Staining

The amyloid plaque staining was conducted as described by Chishti et al. [

23]. Brain slices were incubated in thioflavine S (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA), which is a fluorescent dye specific for amyloid plaques. Following incubation, the samples underwent treatment with alcohol to differentiate and dehydrate the plaques. After drying in the dark, the samples were examined for amyloid plaque (Ap) deposition using a Nikon microscope (Eclipse 90i; Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, USA).

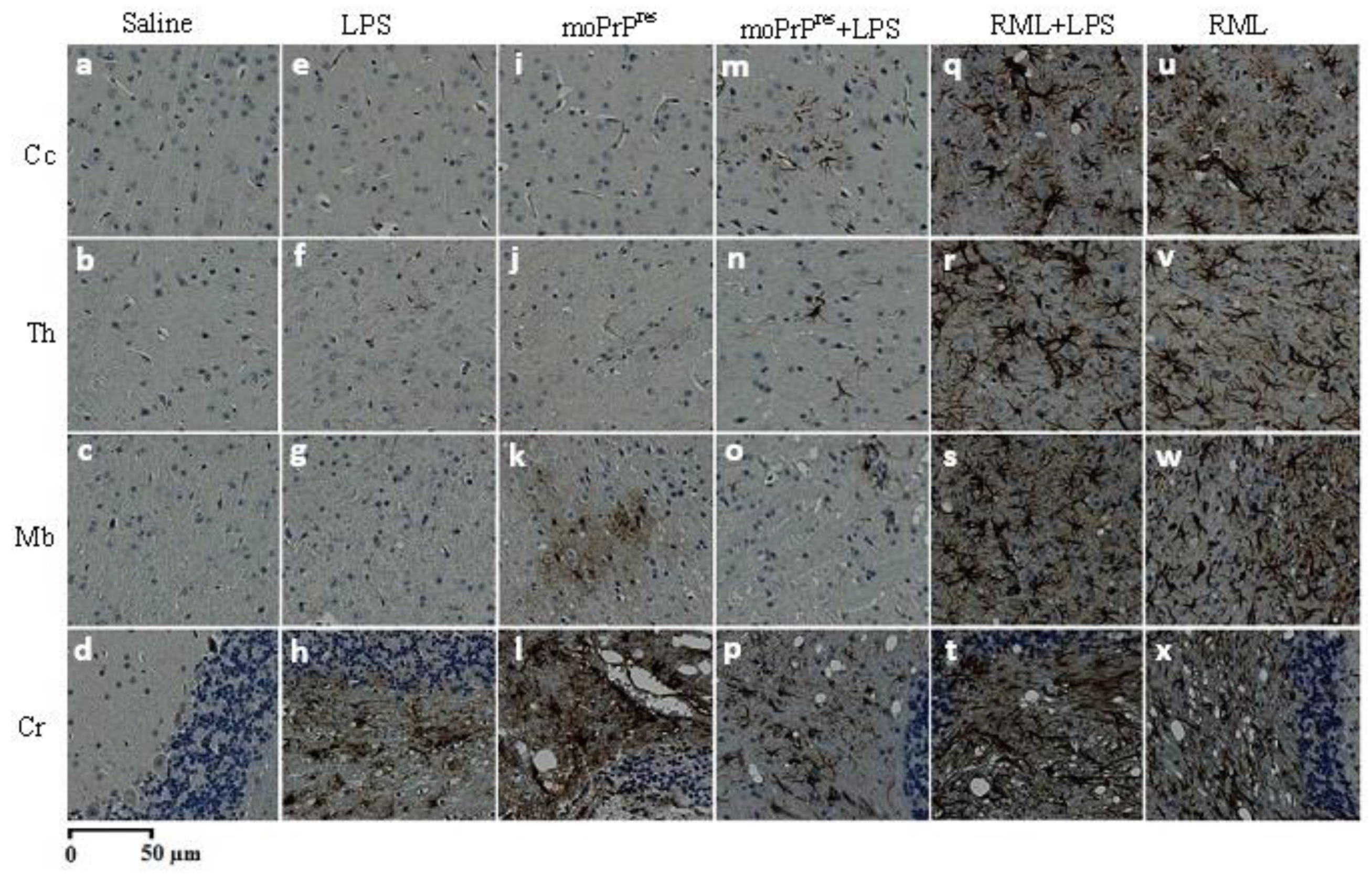

7.10. Astrogliosis Staining

Astrogliosis staining was performed using the methodology established by Chishti et al. [

23]. Following initial processing, brain slides were treated with a glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA; BD Pharmingen, Mississauga, Canada) to label reactive astrocytes. The samples were then incubated with streptavidin-peroxidase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) for 16 minutes, followed by treatment with DAB (BD Pharmingen, Mississauga, Canada) for up to 20 minutes to develop the characteristic brown color indicative of GFAP presence. A counterstaining with Mayer’s Hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) was also performed. Subsequently, brain slices were treated with xylene (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) for clearing. Finally, the slides were mounted with Cytoseal (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) and left to dry at room temperature for 48 hours.

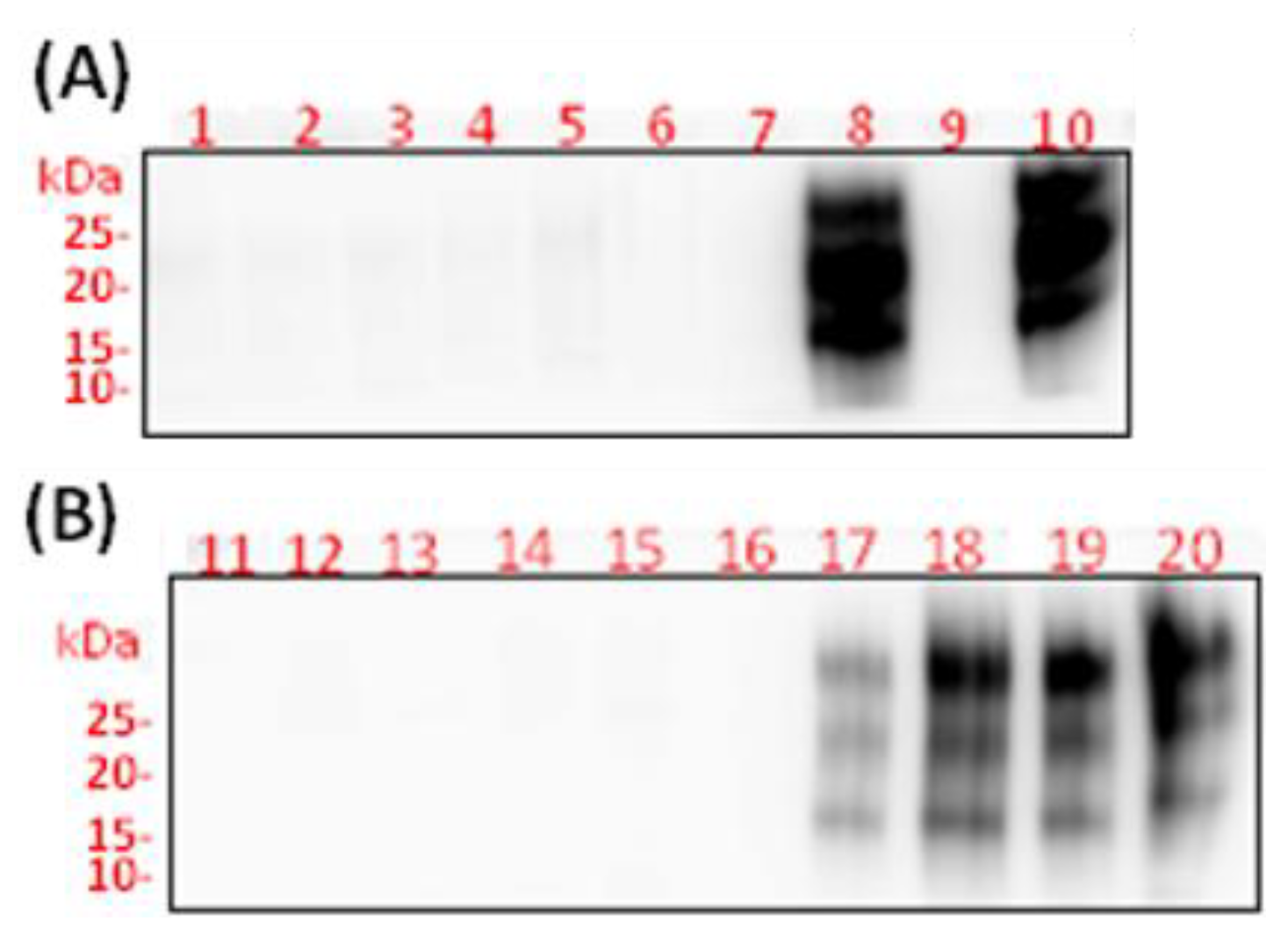

7.11. Western Blot Assay

Brain and spleen samples were prepared to create a 10% tissue homogenate in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (1X; Bio-RAD, Hercules, USA). The total protein concentration was quantified using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA), with 250 µg of protein obtained from brain samples and 400 µg from spleen samples. Each protein sample was then diluted in 250 µL of radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (RIPA; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA), and 50 µg/mL of proteinase K (PK) was added to the homogenate.

To facilitate visualization, 2 µL of 0.02% bromophenol blue (Bio-RAD, Hercules, USA) was incorporated into the solution. The samples were briefly vortexed and allowed to digest with PK for one hour at 37 °C. The reaction was subsequently terminated by adding 25 µL of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) to achieve a final concentration of 5 mM (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). After cooling the samples at room temperature for 5 minutes, they were centrifuged at 20,000 g for 60 minutes at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and 15 µL of 2X sample buffer (SB) was added to the resulting pellet, followed by boiling for 10 minutes to denature the proteins.

Each sample (20-25 µL) was loaded into the corresponding wells of NuPAGE Bis-Tris mini gels (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA). The samples were then subjected to electrophoresis using a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) apparatus (Bio-RAD, Hercules, USA) at 200 volts for 50 minutes. Chemiluminescent molecular weight standards (Precision Plus Protein™ WesternC Standards, Bio-RAD, Hercules, USA) were included in each gel for reference.

Membrane transfer was performed overnight using a wet Western blotting apparatus (Bio-RAD, Hercules, USA) at a voltage of 20 volts. Following the transfer, membranes were quickly rinsed in 1X TBS-Tween (0.5%; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) and incubated with the prion protein monoclonal Sha31 antibody (1:30,000; Bertin Pharma, Montigny le Bretonneux, France) in 1X TBS-Tween (0.5%) overnight at 4 °C. After washing, the membranes were incubated with a secondary goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate antibody (1:10,000; Bio-RAD, Hercules, USA) in 1X TBS-Tween (0.1%) containing 5% skim milk (Carnation, Smucker Foods of Canada, Ontario, Canada).

Imaging of the blots was performed using Pierce® ECL Plus Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) and captured with an ImageQuant LAS 4000 series imaging system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Quebec, Canada).

7.12. Scrapie Cell Assay

The standard scrapie cell assay methodology was adapted from Mahal et al. [

25]. In this assay, L929 mouse fibroblast cells (ATCC, Manassas, USA) were exposed to prion samples prepared as brain homogenates in 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a concentration of 10%. A series of control samples, including saline (negative control),

Escherichia coli 0111

Lipopolysaccharide, moPrPres, moPrPres+LPS, RML+LPS, and RML (positive control), were prepared at a volume of 30 µL each and loaded into a 96-well tissue culture plate (Corning Costar, Tewksbury, USA). The samples underwent a dilution series ranging from 0.1% to 0.0001% and were tested in six replicates. To each well, 20 µL of a cell suspension containing approximately 5,000 L929 cells was added.

The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 3-5 minutes before adding 150 µL of Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% horse serum (Sigma, St. Louis, USA). Following this, the plates were placed in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for a total of five days. After the incubation period, the cells were passaged twice (1:4 and 1:7 dilutions), with each passage followed by a 5-day incubation at 37 °C.

To prepare the ELISPOT assay, 96-well ELISPOT plates (Millipore, Billerica, USA) were activated by washing with 70% ethanol (60 µL for 3 minutes; Commercial Alcohol, Winnipeg, Canada) and rinsing three times with 1X TBS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). Thirty µL of 1X TBS was added to the wells to keep the membranes wet, and 20,000 L929 cells were loaded into each well of the ELISPOT plate. The filtered cells on each plate were then subjected to vacuum and dried at 50 °C for one hour.

To digest the cells, 60 µL of RIPA lysis buffer containing 5 µg/mL proteinase K (PK; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) was added to each well. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 90 minutes, after which the lysis buffer was removed, and each well was washed three times with 1X TBS. Subsequently, 100 µL of 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) prepared in TBS was added to each well, and the plates were incubated on a rocker (3D rotator, model 4631, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, USA) at room temperature for 10 minutes. After removing the PMSF, the wells were washed three times with 1X TBS.

Next, 100 µL of 3 M guanidine thiocyanate (GdnSCN; Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) was added to each well, followed by another 10-minute incubation on the rocker at room temperature. Afterward, GdnSCN was removed, and the wells were washed four times with 1X TBS. Subsequently, 100 µL of 5% skim milk (prepared in 1X TBS; Carnation®, Alberta, Canada) was added, and the plates were incubated at room temperature for 60 minutes. After removing the milk and washing three times with 1X TBS, the primary antibody (SAF83, 1:1,000 dilution in 1X TBS; Cayman Chemical, Michigan, USA) was added and incubated on the rocker for 120 minutes at room temperature. Following this, the SAF83 was washed away with three rinses of 1X TBS, and the secondary antibody (1:5,000 dilution, goat anti-mouse alkaline phosphatase conjugate; Bio-RAD, Hercules, USA) was added for a 90-minute incubation at room temperature on the rocker.

After removing the secondary antibody with three washes of 1X TBS, 60 µL of alkaline phosphatase buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2·6H2O; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) was added to each well, followed by a 10-minute incubation on the rocker. The alkaline phosphatase buffer was then removed, and 60 µL of BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate)/NBT (nitro blue tetrazolium) substrate solution (Promega, Madison, USA) was added, with subsequent incubation for 20 minutes. Following this, the BCIP/NBT solution was removed, and the wells were washed four times with distilled water. The plates were then allowed to dry overnight in the dark.

7.13. Statistics

Weight trends were analyzed using the MIXED procedure in SAS (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The statistical model utilized for the analysis was as follows:

In this equation, Yijkl represents the dependent variable, μ is the population mean, ti denotes the fixed effect of treatment, pj indicates the fixed effect of the period (age in weeks), tpij accounts for the interaction between treatment and period, and εijkl represents the residual error, which is assumed to follow a normal distribution. The degrees of freedom were calculated using the Kenward-Roger method. Results were presented through comparisons of least squares means, utilizing the SAS probability difference option. The significance level was set at a cut-off value of P < 0.05. Additionally, survival analysis was performed using PRISM software (Prism Software Corporation) to evaluate differences in survival rates across treatment groups.

8. Conclusions

Overall, this work provides multiple paradigm-shifting insights for prion biology and the broader field of neurodegenerative disorders:

1. Pathogenic moPrPRes without detectable PrPSc: We demonstrate that purely recombinant prion protein, converted in vitro with LPS but lacking classical PrPSc, can still induce neurodegeneration in wild-type mice.

2. LPS-driven Alzheimer’s-like pathology: Prolonged subcutaneous LPS exposure (6 weeks) alone is sufficient to cause widespread brain vacuolation, neuroinflammation, and a substantial mortality rate in otherwise healthy animals, suggesting that chronic bacterial endotoxin exposure may be a key driver of non-prion neurodegeneration.

3. Synergistic impact of LPS and RML: Co-administration of LPS with a classical prion strain (RML) dramatically exacerbates pathological outcomes, accelerating mortality and increasing spongiform changes and astrogliosis, thereby reinforcing the importance of inflammatory cofactors in prion diseases.

Ultimately, these insights underscore the multifactorial nature of prion diseases and highlight the importance of investigating similar inflammatory mechanisms in other protein misfolding syndromes. Further mechanistic work is warranted to dissect the molecular foundations of moPrPRes-induced neurodegeneration and to leverage these discoveries in the pursuit of novel strategies to prevent or mitigate prion-like disorders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, David Wishart and Burim Ametaj; Data curation, Grzegorz Zwierzchowski, Seyed Ali Goldansaz, Dagnachew Hailemariam and Burim Ametaj; Funding acquisition, David Wishart and Burim Ametaj; Investigation, Seyed Ali Goldansaz, Dagnachew Hailemariam, Elda Dervishi, David Wishart and Burim Ametaj; Methodology, David Wishart and Burim Ametaj; Project administration, David Wishart and Burim Ametaj; Resources, Roman Wójcik, David Wishart and Burim Ametaj; Validation, Seyed Ali Goldansaz, Dagnache Hailemariam, and Burim Ametaj; Writing – original draft, Seyed Ali Goldansaz, Dagnache Hailemariam, and Burim Ametaj; Writing – review & editing, Grzegorz Zwierzchowski, Seyed Ali Goldansaz, Dagnachew Hailemariam, Elda Dervishi, Roman Wójcik, David Wishart and Burim Ametaj. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

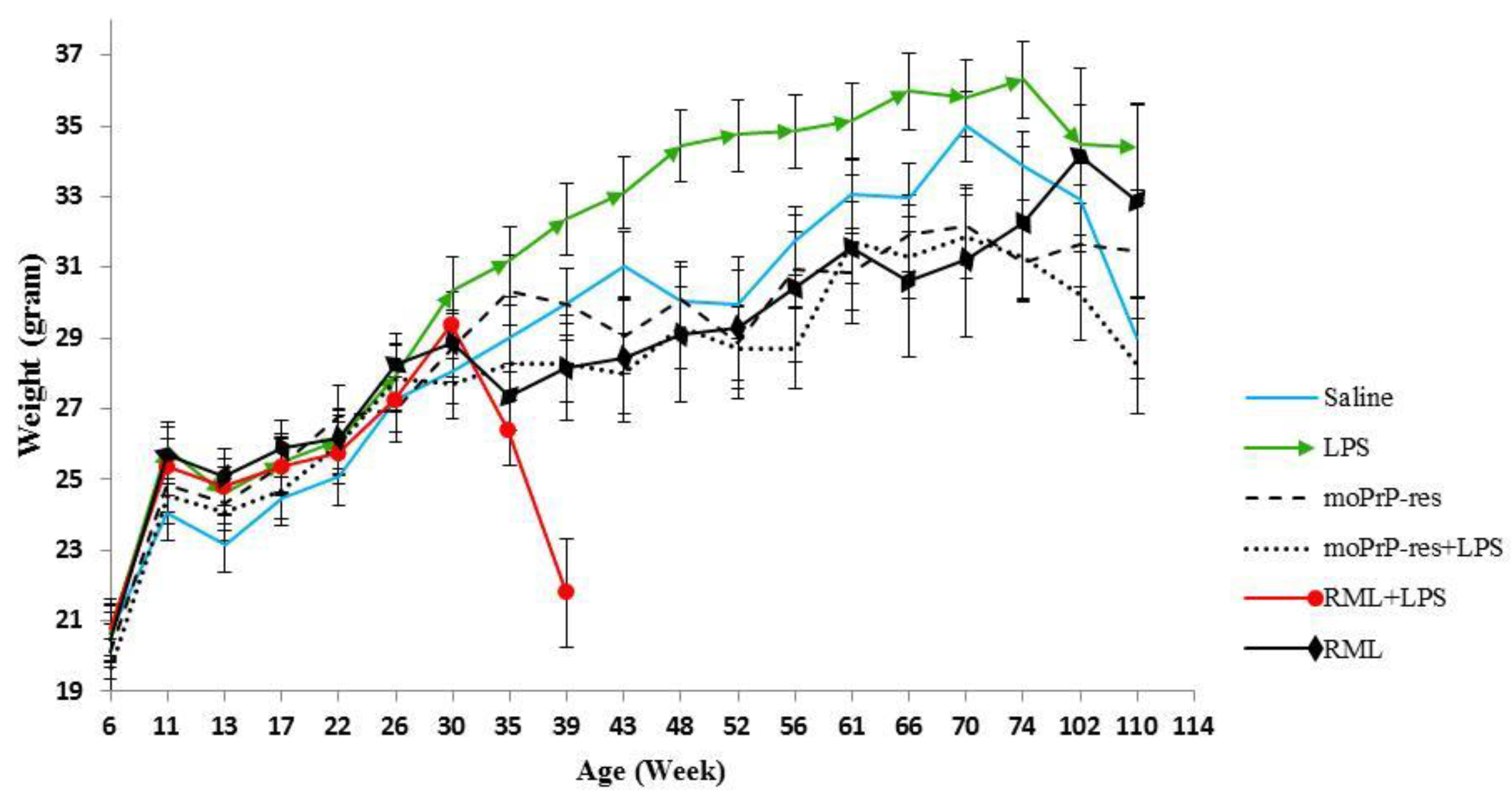

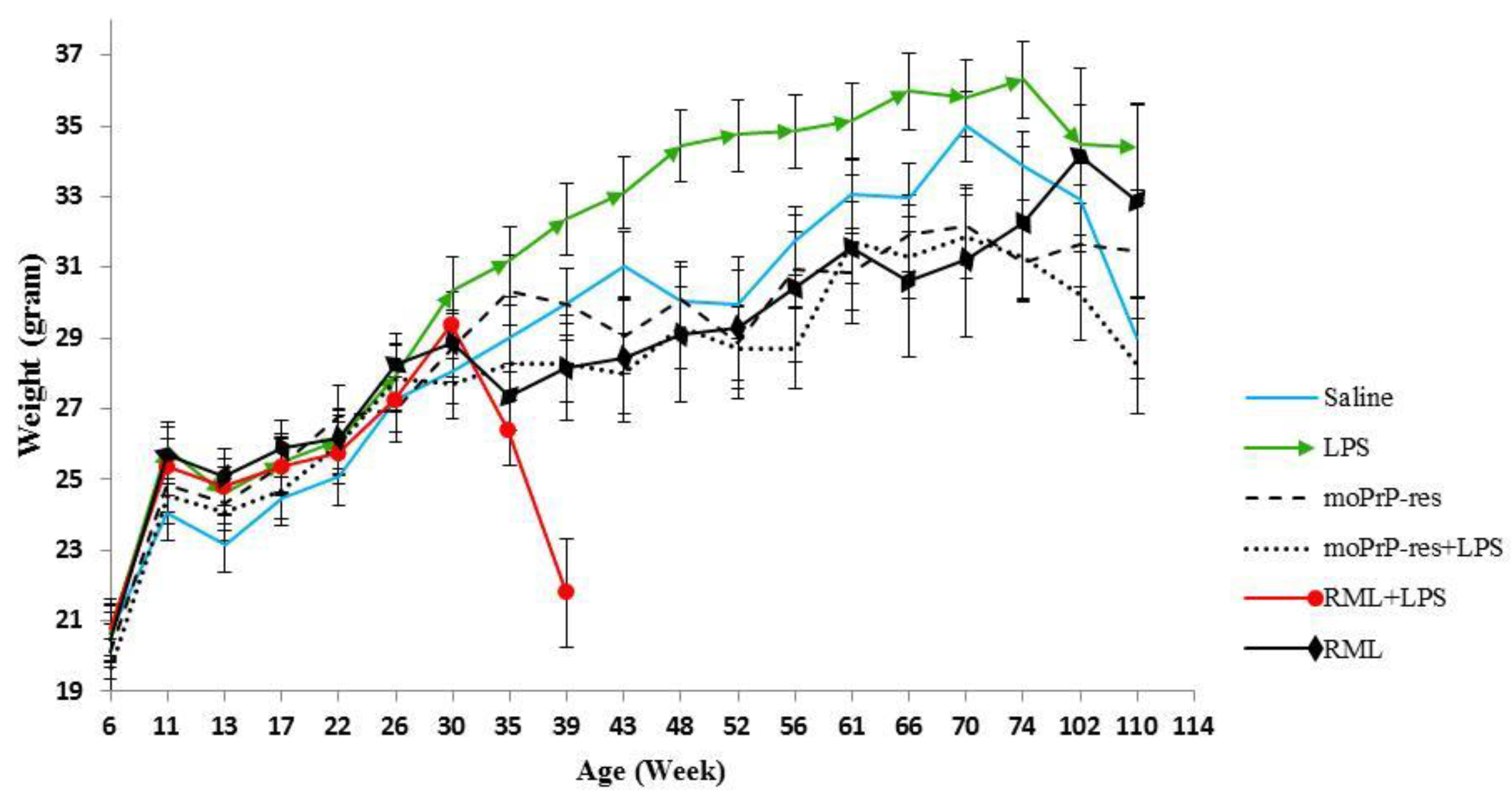

Figure 1.

Monthly weights of different treatment groups, including saline (negative control), bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), mouse recombinant PrP proteinase-K resistant (moPrPres), moPrPres+LPS, RML+LPS, and RML (positive control). Lipopolysaccharide or saline were administered subcutaneously for 6 weeks through ALZET® osmotic mini pumps (ALZET, Cupertino, CA). A single injection of moPrPres or RML was administered at the time of mini pump implantation. Statistical comparisons indicate significant differences between LPS vs. RML (at 35, 39, 43, 48, 52, and 66 weeks), LPS vs. saline (48, 52, 56, 66, and 110 weeks; marked with a star), LPS vs. RML+LPS (35 and 39 weeks), LPS vs. moPrPres (43, 48, 52, 56, 61, 66, 70, and 74 weeks), LPS vs. moPrPres + LPS (39, 43, 48, 52, 56, 61, 66, 70, 74, 102, and 110 weeks), moPrPres vs. RML (35 weeks), moPrPres vs. RML+LPS (35 and 39 weeks), moPrPres+LPS vs. RML+LPS (39 weeks), moPrPres+LPS vs. saline (56 and 70 weeks), RML vs. RML+LPS (39 weeks), and RML+LPS vs. saline (39 weeks).

Figure 1.

Monthly weights of different treatment groups, including saline (negative control), bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), mouse recombinant PrP proteinase-K resistant (moPrPres), moPrPres+LPS, RML+LPS, and RML (positive control). Lipopolysaccharide or saline were administered subcutaneously for 6 weeks through ALZET® osmotic mini pumps (ALZET, Cupertino, CA). A single injection of moPrPres or RML was administered at the time of mini pump implantation. Statistical comparisons indicate significant differences between LPS vs. RML (at 35, 39, 43, 48, 52, and 66 weeks), LPS vs. saline (48, 52, 56, 66, and 110 weeks; marked with a star), LPS vs. RML+LPS (35 and 39 weeks), LPS vs. moPrPres (43, 48, 52, 56, 61, 66, 70, and 74 weeks), LPS vs. moPrPres + LPS (39, 43, 48, 52, 56, 61, 66, 70, 74, 102, and 110 weeks), moPrPres vs. RML (35 weeks), moPrPres vs. RML+LPS (35 and 39 weeks), moPrPres+LPS vs. RML+LPS (39 weeks), moPrPres+LPS vs. saline (56 and 70 weeks), RML vs. RML+LPS (39 weeks), and RML+LPS vs. saline (39 weeks).

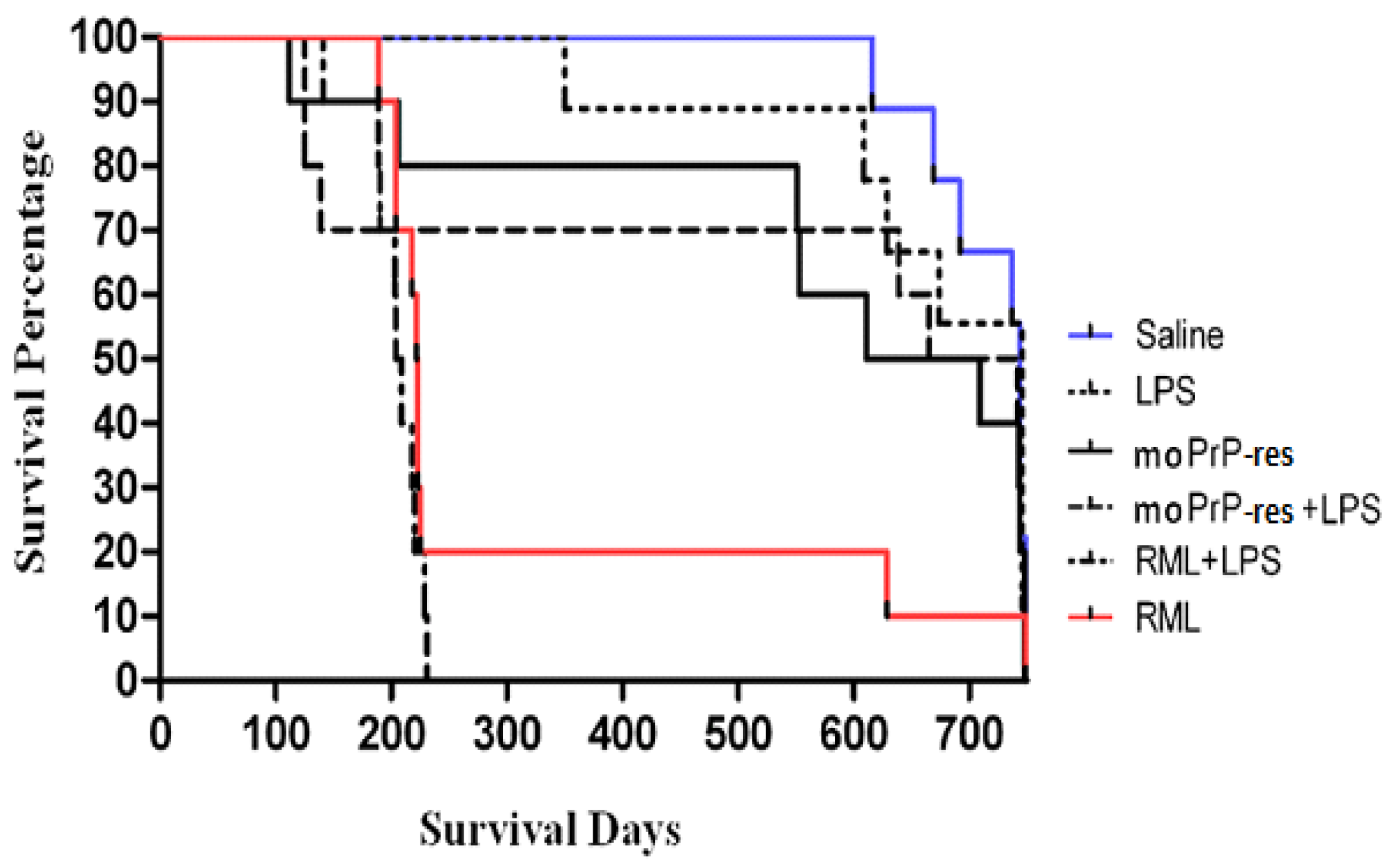

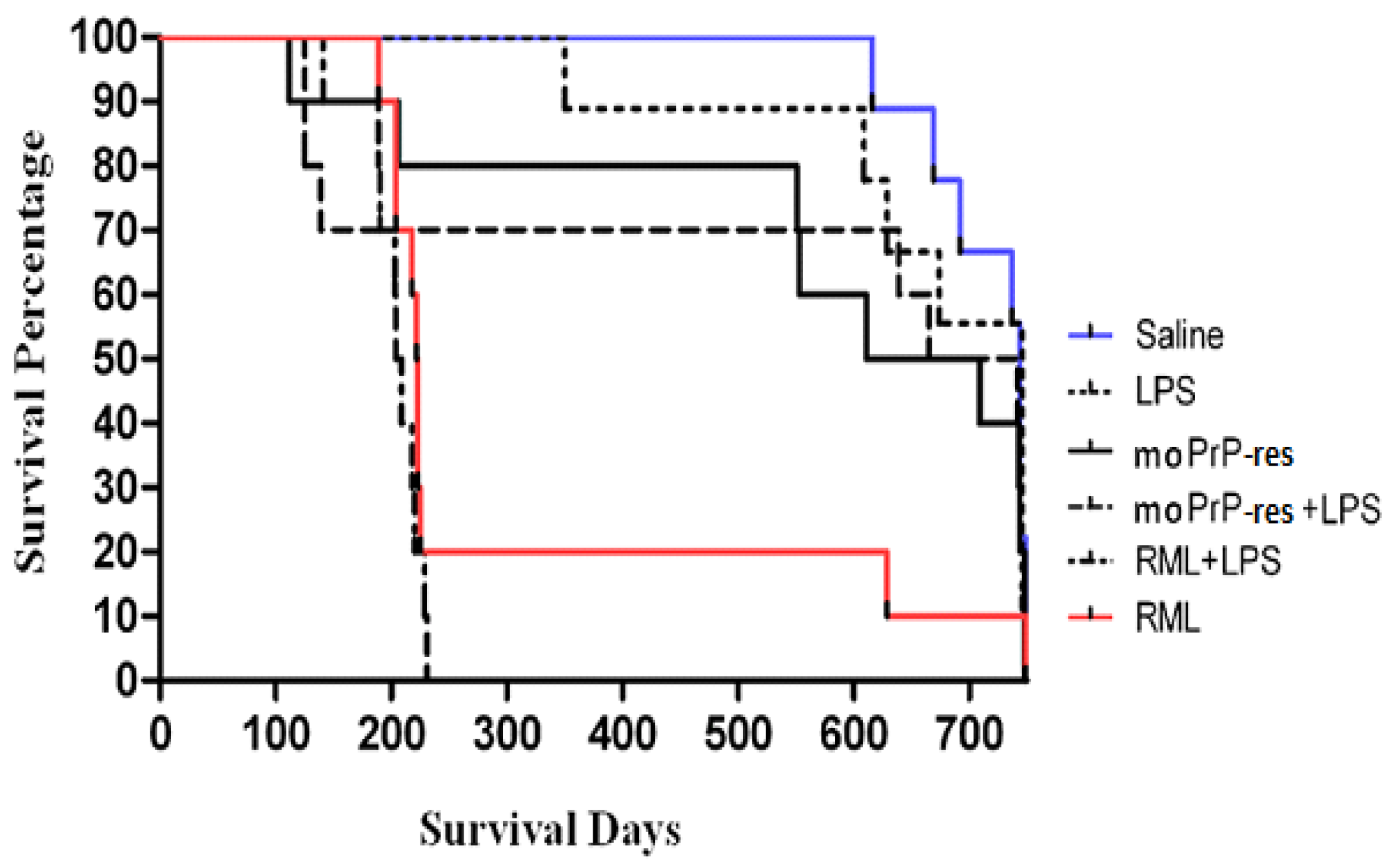

Figure 2.

Survival analysis of terminally sick FVB/N female mice. All mice were monitored for clinical signs of prion disease until 750 days post-inoculation and were subsequently euthanized or found dead after maintaining clinical signs for a minimum of 72 h. Negative controls (saline-treated animals) exhibited no clinical signs of prion disease, with all being found dead in the cage without prior symptoms. Most treated animals were euthanized or found dead with clinical signs resembling prion disease. Twenty percent of the RML positive controls survived until the termination of the experiment. The combination of RML with LPS caused earlier mortality (within 100–150 days), with all mice dead by 200 days. Sixty percent of the moPrPres-treated mice died before termination, with four showing clinical signs of neurodegeneration. The moPrPres+LPS treatment group had a mortality rate of 50%, with three mice showing clinical signs. Additionally, 40% of the LPS-treated animals exhibited clinical signs and were subsequently euthanized.

Figure 2.

Survival analysis of terminally sick FVB/N female mice. All mice were monitored for clinical signs of prion disease until 750 days post-inoculation and were subsequently euthanized or found dead after maintaining clinical signs for a minimum of 72 h. Negative controls (saline-treated animals) exhibited no clinical signs of prion disease, with all being found dead in the cage without prior symptoms. Most treated animals were euthanized or found dead with clinical signs resembling prion disease. Twenty percent of the RML positive controls survived until the termination of the experiment. The combination of RML with LPS caused earlier mortality (within 100–150 days), with all mice dead by 200 days. Sixty percent of the moPrPres-treated mice died before termination, with four showing clinical signs of neurodegeneration. The moPrPres+LPS treatment group had a mortality rate of 50%, with three mice showing clinical signs. Additionally, 40% of the LPS-treated animals exhibited clinical signs and were subsequently euthanized.

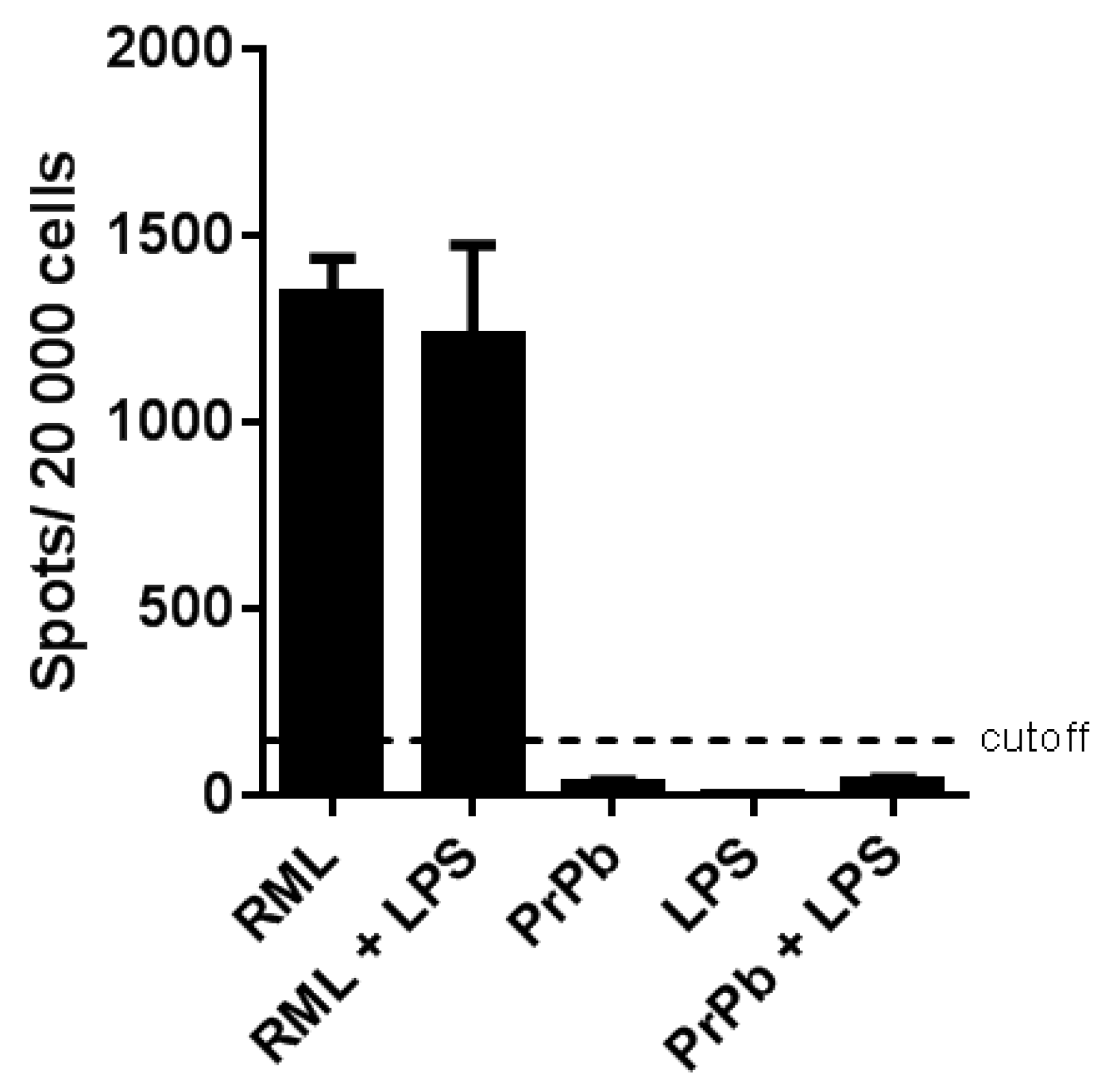

Figure 10.

Scrapie cell assay utilizing the L929 mouse fibroblast cell line and brain homogenates from terminally sick FVB/N female mice. Three brain homogenates from each of the terminally sick LPS, moPrPRes, moPrPRes+LPS, RML+LPS, and RML treatment groups were exposed to L929 cells in a dilution series of 0.1% to 0.0001%, with six replicates per dilution. The cut-off value was set at 150 spots/20,000 cells.

Figure 10.

Scrapie cell assay utilizing the L929 mouse fibroblast cell line and brain homogenates from terminally sick FVB/N female mice. Three brain homogenates from each of the terminally sick LPS, moPrPRes, moPrPRes+LPS, RML+LPS, and RML treatment groups were exposed to L929 cells in a dilution series of 0.1% to 0.0001%, with six replicates per dilution. The cut-off value was set at 150 spots/20,000 cells.