Submitted:

21 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

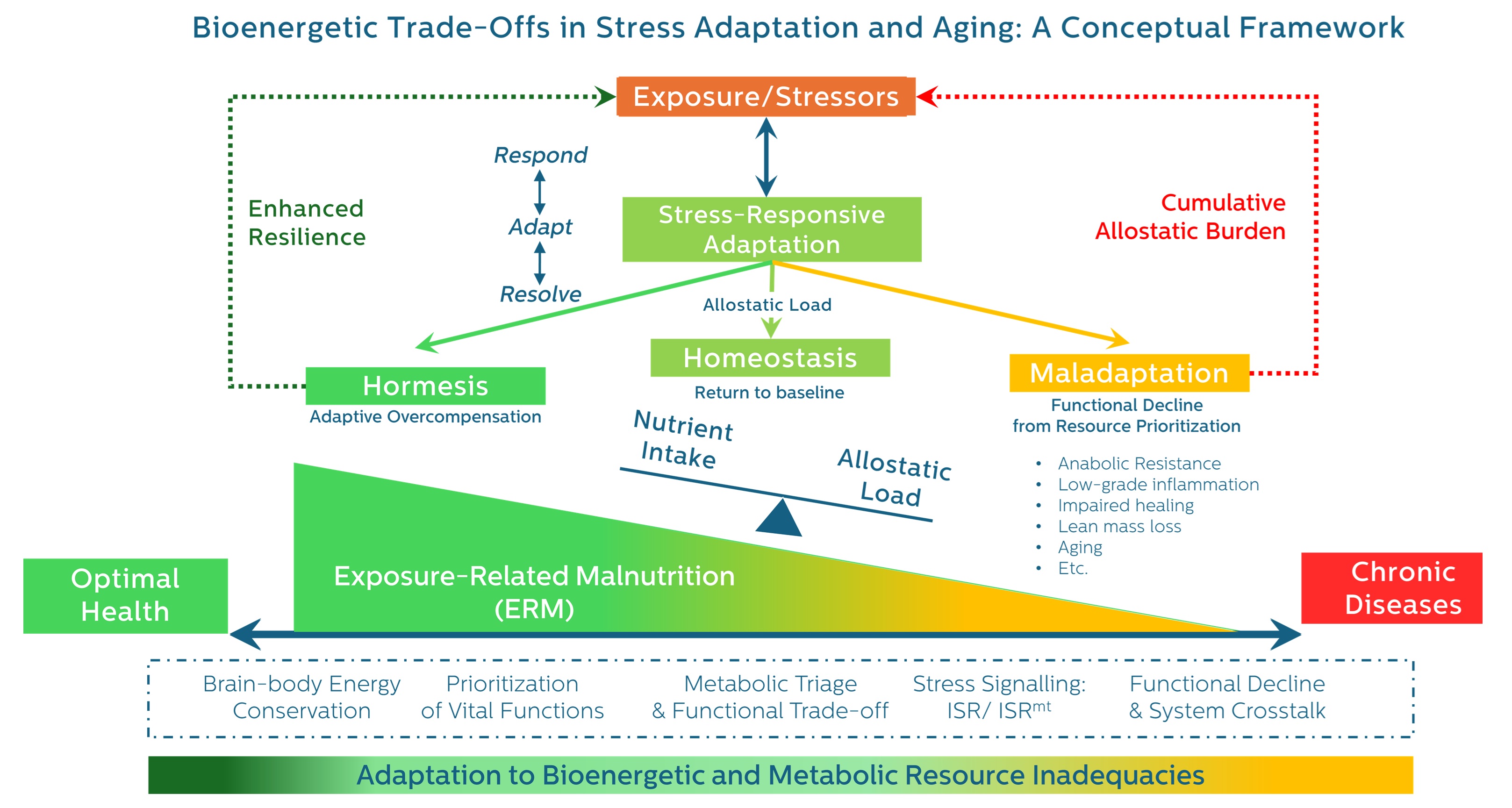

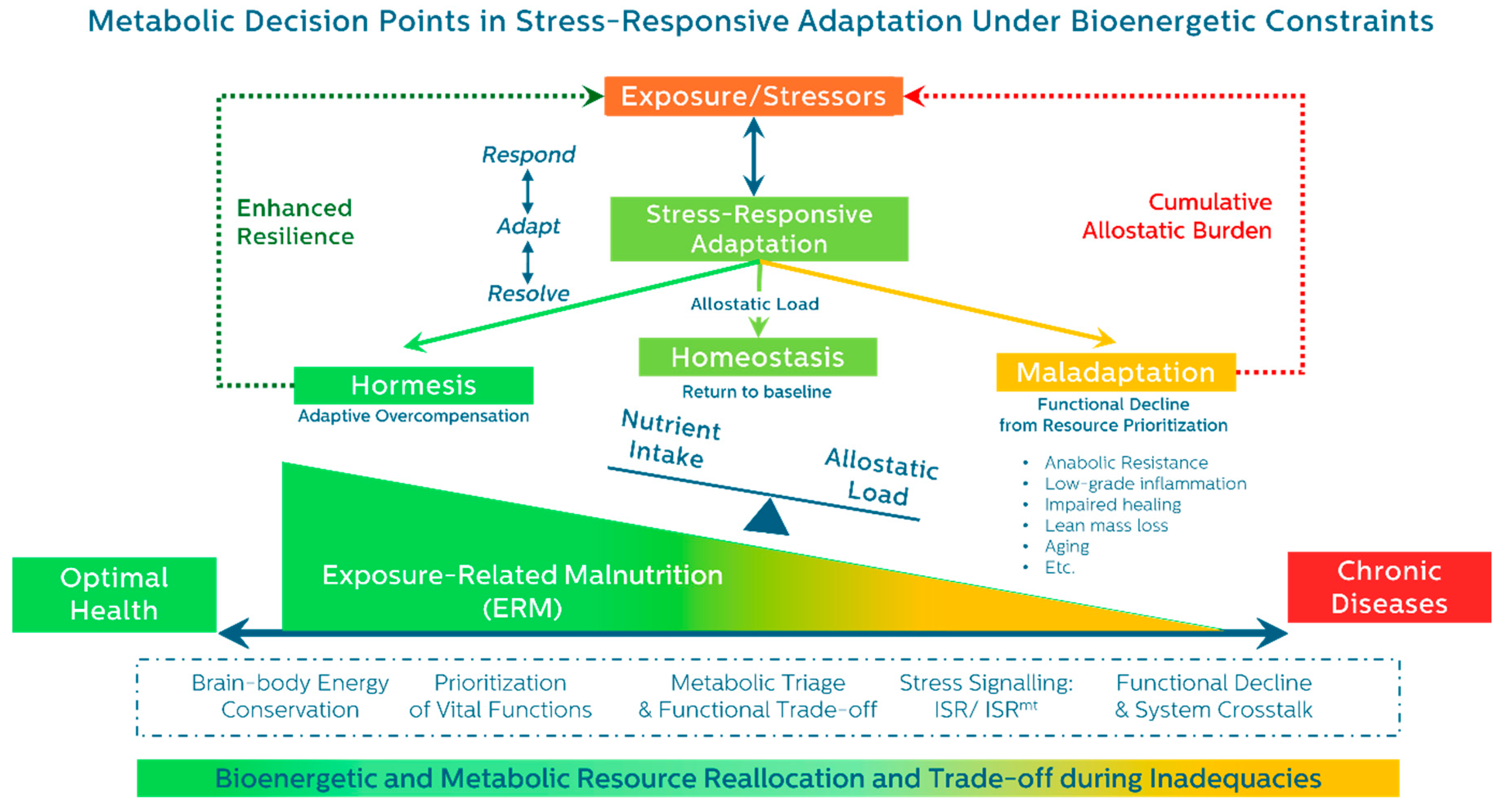

While global lifespan continues to rise, healthspan—the period of life spent in good health—remains stagnant or in decline. This widening gap reflects more than chronic disease burden; it signals the hidden metabolic cost of prolonged stress adaptation. Under sustained physiological strain, the body reallocates energy and nutrients away from maintenance and repair toward short-term survival priorities such as immune defense and glucose mobilization. Although initially protective, these trade-offs progressively impair recovery, erode resilience, and accelerate biological aging.

Current stress and aging frameworks, including allostatic load, describe cumulative burden but lack the resolution to detect early, reversible stages of metabolic compromise—especially in individuals without weight loss or intake deficiency. To address this, we propose Exposure-Related Malnutrition (ERM): a subclinical condition marked by chronic substrate misallocation under stress, despite adequate caloric intake or BMI. ERM represents an early inflection point of adaptive failure with implications for aging, resilience, and chronic disease.

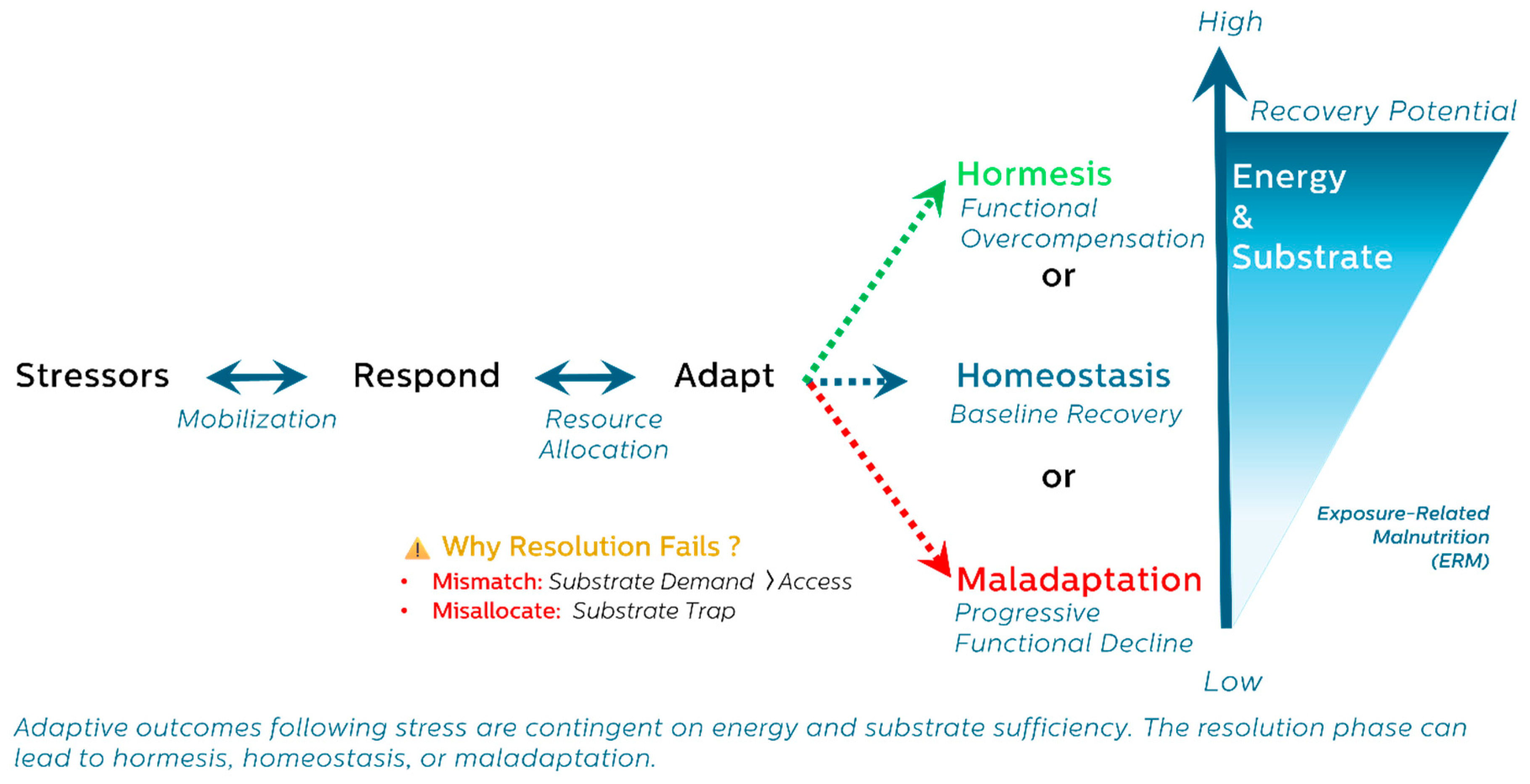

This thematic narrative review integrates findings from endocrinology, immunometabolism, mitochondrial biology, and systems physiology. We present a unifying three-phase model of stress response—Respond → Adapt → Resolve—and show how bioenergetic constraints during the resolution phase shape divergent outcomes: homeostasis, hormesis, or maladaptation.

Clinically, ERM reframes unexplained fatigue, anabolic resistance, or immune dysfunction as signs of early metabolic imbalance. Recognizing ERM enables earlier detection and supports biomarker-guided, resilience-informed interventions aimed at preserving healthspan by addressing the energetic cost of unresolved adaptation.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Paradox of Longevity: Rising Lifespan, Declining Healthspan

1.2. A Critical Gap in Stress and Aging Models

1.3. Purpose and Scope: Introducing ERM as a Conceptual Bridge

- Identifying a reversible stage of adaptation failure that precedes traditional disease markers;

- Integrating energy availability and substrate allocation as central regulators of stress resolution and resilience;

- Bridging molecular stress models with clinical presentations; and

- Providing a systems-level framework for early detection and intervention before irreversible aging-related decline.

1.4. Structure of the Review

- Energetic adaptation: We describe the trajectory of stress response using the Respond → Adapt → Resolve framework and outline how this process may lead to homeostasis, hormesis, or maladaptation.

- System-level trade-offs: We examine how neuroendocrine, immune, muscular, mitochondrial, and cellular networks navigate energetic constraints and reallocate resources under stress.

- Clinical implications: We outline the presentation, staging, and early biomarkers of ERM and propose practical strategies for detection, intervention, and prevention of chronic disease rooted in adaptive energy failure.

2. Methodology: A Thematic Narrative Review

3. The Energetic Trajectory of Stress Adaptation: From Response to Resolution

3.1. General Adaptation and the Cost of Resolution

- Restored homeostasis

- Adaptive overcompensation (hormesis)

- Progressive maladaptation and decline (exhaustion)

3.2. Hormesis: A Metabolic Bet on Adaptive Remodeling

3.3. Substrate Limitation and Trade-Offs

3.4. A Unifying Trajectory: Respond → Adapt → Resolve

- Phase 1: Respond – Emergency mobilization of energy and substrate.

- Phase 2: Adapt – Resource reallocation, stress programming, and metabolic reprioritization.

- Phase 3: Resolve – Withdrawal of stress programs, restoration of balance, or collapse into dysfunction.

4. The Energetic Architecture of Adaptation: Substrate Reallocation in Systemic Stress Responses

4.1. Phase 1—Respond: Emergency Signaling and Energy Mobilization

- Neuroendocrine System: The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) system initiate a coordinated stress response, rapidly mobilizing glucose while suppressing growth and reproduction (Tsigos & Chrousos, 2002).

- Immune System: Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) activate acute inflammation and drive metabolic polarization toward glycolysis, supporting cytokine production (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) (Alack et al., 2019; Straub, 2017).

- Skeletal muscle: Acts as a metabolic reservoir, supplying gluconeogenic substrates through proteolysis (Cahill, 2006; Wolfe, 2006).

- Cellular ISR halts general protein synthesis via eIF2α phosphorylation while promoting selective translation of stress-resilient genes (Pakos-Zebrucka et al., 2016).

- Mitochondria toward ATP generation, activate antioxidant pathways, and initiate the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) (Picard & Shirihai, 2022).

4.2. Phase 2— Adapt: Metabolic Prioritization and Stress Programming

- Neuroendocrine System: Cortisol orchestrates systemic prioritization, supporting cerebral glucose supply while suppressing insulin, growth, and reproduction (McEwen & Wingfield, 2003).

- Immune cells undergo metabolic polarization: pro-inflammatory cells rely on glycolysis, while regulatory or reparative cells depend on oxidative phosphorylation (Olenchock et al., 2017; Willmann & Moita, 2024) (Geric et al., 2019; Olenchock et al., 2017). Chronic stress can trap cells in inflammatory states.

- Skeletal muscle, a major metabolic sink, attempts to transition from catabolism to repair. This shift requires amino acid availability and immune–muscle coordination, both of which are impaired under conditions of anabolic resistance. Anabolic resistance is not only a consequence but also a signal of unresolved adaptation, a state in which substrates and signaling are insufficient to restore muscle regeneration (Paulussen et al., 2021).

- Cellular ISR, when energetically supported, transitions from acute translation suppression to remodeling via autophagy, stress granule formation, and selective translation of repair-promoting factors (Gambardella et al., 2020). This metabolic reprioritization also drives epigenetic remodeling that accelerates cellular aging, especially under persistent stress (Gambardella et al., 2020).

- Mitochondria undergo remodeling, including mitophagy, fission/fusion dynamics, and shifts in substrate utilization to meet tissue-specific energy demands (Lockhart et al., 2020).

4.3. Phase 3—Resolve: Transitioning from Adaptation to Outcome

- Neuroendocrine system downregulates HPA activity and reinstates circadian and metabolic rhythms. Persistent flattening of cortisol indicates impaired resolution (McEwen, 2007; Sapolsky, 2004).

- Immune systems transition from inflammation to repair, with M1 macrophages converting to M2 phenotypes and resolution pathways (e.g., resolvins, lipoxins) facilitating tissue remodeling (Olenchock et al., 2017). Micronutrient sufficiency—particularly zinc, selenium, and iron—is critical to this process.

- Skeletal muscle resumes protein synthesis and regeneration, but only if inflammation resolves and energy/nutrient levels support mTORC1 and satellite cell activation. Without adequate support, fibrosis or sarcopenia may ensue (Paulussen et al., 2021).

- Cellular ISR mechanisms, such as GADD34-mediated dephosphorylation of eIF2α, permit selective restoration of protein synthesis. This reactivation depends on sufficient ATP, proteostasis, and redox control (Gambardella et al., 2020).

- Mitochondria stabilize through restored fission/fusion dynamics and mitophagy, allowing redox homeostasis and efficient energy production. Transient mitokine signaling subsides as systemic demands normalize (Picard & Shirihai, 2022).

5. Resolution and Its Consequences: Divergent Outcomes Shaped by Energy and Resource Allocation

- Homeostasis – restoration of baseline function

- Hormesis – adaptive overcompensation and enhanced resilience

- Maladaptation – incomplete resolution and functional deterioration

5.1. Homeostasis: Energetic Recovery and Structural Recalibration

- Neuroendocrine recovery: HPA axis normalization and restored circadian rhythm with cortisol and sympathetic output declining. Parasympathetic tone is restored, and insulin sensitivity improves (Bobba-Alves et al., 2022).

- Immune recalibration: Immune resolution involves clearance of apoptotic cells, matrix remodeling, and macrophage transition from M1 to M2 phenotypes—processes that rely on mitochondrial OxPhos, redox regulation, and micronutrients like zinc, iron, and selenium (Alack et al., 2019; Laurent et al., 2017; Olenchock et al., 2017).

- Muscle regeneration: Recovery depends on satellite cell activation and nutrient-sensitive pathways such as mTORC1, supported by leucine, vitamin D, and redox cofactors (Beaudart et al., 2017; Careccia et al., 2023; Paulussen et al., 2021).

- Cellular ISR resolves through GADD34-mediated dephosphorylation of eIF2α, enabling proteostasis and selective translation restoration (Gambardella et al., 2020; Novoa et al., 2001).

- Mitochondrial recovery via mitophagy and biogenesis restores ATP production and oxidative balance; transient ROS bursts activate adaptive pathways via NRF2 and FOXO, while sustained oxidative stress impairs recovery (Picard & Shirihai, 2022).

5.2. Hormesis: Energetic Overcompensation and Adaptive Remodeling

- Trained immunity: Monocytes, macrophages, and NK cells undergo glycolytic and epigenetic reprogramming via mTOR–HIF-1α signaling, increasing responsiveness and tolerance (Netea et al., 2016; Ochando et al., 2023; Vuscan et al., 2024).

- Immune resolution and tolerance: Regulatory T cells and M2 macrophages mediate inflammation resolution and tissue repair via mitochondrial metabolism (Vuscan et al., 2024).

- Exercise-induced muscle remodeling: IL-13–producing ILC2s, IL-33–expressing stromal cells, and macrophage–Treg signaling coordinate mitochondrial biogenesis and type 2 immunity in recovery (Langston & Mathis, 2024; Metallo & Vander Heiden, 2013).

- Mild ISR activation: Transient eIF2α phosphorylation enhances redox balance, proteostasis, and metabolic flexibility via ATF4/CHOP signaling (Costa-Mattioli & Walter, 2020; Sparkenbaugh et al., 2011).

- Mitohormesis: Low-level ROS from mitochondrial stress induces biogenesis, antioxidant upregulation, and mitokine release (e.g., FGF21, MOTS-c) for systemic coordination (Lockhart et al., 2020; Ristow & Schmeisser, 2014).

5.3. Maladaptation: Energetic Collapse and Structural Degeneration

- Neuroendocrine: Sustained cortisol, insulin resistance, hippocampal atrophy, and central fatigue due to prolonged stress signaling (Chrousos, 2009; Meeusen et al., 2006; Shaulson et al., 2024).

- Immune: Inflammaging and immunosenescence from persistent IL-6, TNF-α, SASP signaling, and impaired clearance of senescent cells(Franceschi et al., 2018; Fulop et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2024).

- Skeletal muscle: Anabolic resistance, mitochondrial dysfunction, and catabolism lead to sarcopenia and frailty, compounded by aging, nutrient deficits, and inflammation(Cruz-Jentoft et al., 2023; Walrand et al., 2021).

- Cellular ISR: Chronic eIF2α phosphorylation impairs translation, promotes apoptosis, and drives redox imbalance and mitochondrial damage (Hetz & Papa, 2018; Wek, 2018).

- Mitochondria: PGAM5-driven mitochondrial fragmentation, ROS generation, and mtDNA-triggered inflammasome activation fuel a cycle of mitophagy failure, pyroptosis, and degeneration (Qi et al., 2025; Youle & van der Bliek, 2012; Yuk et al., 2020)

5.4. Interpreting Resolution as a Metabolic Decision Point

- Stressor burden and duration

- Substrate availability and recovery efficiency

- System-specific thresholds for adaptation or collapse.

6. Recognizing the Spectrum of Malnutrition: From Demand to Distribution Dysfunction

6.1. Demand-Driven Malnutrition: Elevated Needs, Silent Deficits

- Disease-Related Malnutrition (DRM): Triggered by inflammation-induced hypermetabolism and catabolism in acute or chronic disease, even when feeding is maintained (Cederholm & Bosaeus, 2024; Muscaritoli et al., 2023).

- Chronic Energy Deficiency (CED): Seen in conditions like pregnancy or undernutrition in low-resource settings, where demand outpaces supply despite normal or near-normal BMI (Prisabela et al., 2023; Taylor-Baer & Herman, 2018).

- Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs): Affects athletes with chronic low energy availability, leading to multisystem compromise despite preserved weight or caloric intake (Cabre et al., 2022; Mountjoy et al., 2018).

6.2. Substrate Trapping: When Energy Is Present but Misallocated

6.3. Type 5 Diabetes: A Visible Phenotype of Stress-Driven Reallocation

6.4. ERM: A Preclinical Framework of Bioenergetic Adaptation Failure

- No overt intake deficit – energy intake may appear normal, and BMI may be stable or elevated.

- Triggered by cumulative exposome burden – including inflammation, toxin exposure, psychosocial stress, circadian disruption, or chronic low-grade infections (Pizzorno, 2020; Vermeulen et al., 2020).

- Manifests through the metabolic trade-offs pattern – such as impaired muscle recovery, fatigue, immunosuppression, or anabolic resistance, often before clinical thresholds of dysfunction are met.

7. Recognizing ERM in Clinical Practice: From Substrate Trade-Offs to Resilience-Informed Care

7.1. Functional Clues: Detecting ERM Beyond Deficiency

- Chronic fatigue despite adequate sleep and nutrition

- Poor exercise recovery or delayed wound healing

- Frequent mild infections or persistent low-grade inflammation

- Difficulty maintaining or building lean mass despite sufficient intake

- Subtle shifts in lab values suggesting nutrient redistribution

7.2. Drivers of ERM: The Cumulative Exposome

- External triggers: air pollution, persistent organic pollutants (POPs), heavy metals (e.g., lead, arsenic, mercury), microplastics, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and circadian rhythm disruption

- Internal triggers: chronic inflammation, dysbiosis, latent infections, psychosocial stress, and trauma

7.3. Staging ERM: A Functional Continuum of Decline

- Mild ERM: Slight reductions in stamina, cognition, or stress recovery. Reversible with timely substrate support and stress mitigation.

- Moderate ERM: Onset of measurable trade-offs—low-grade inflammation, anabolic resistance, suppressed protein turnover, hormonal shifts.

- Severe ERM: Entrenched catabolism, immune dysfunction, sarcopenia, and system rigidity—often preceding overt disease.

7.4. Biomarkers of Trade-Offs: Functional Patterns over Static Values

- Positive acute-phase proteins (e.g., CRP, ferritin, fibrinogen) increase in response to inflammation.

- Negative acute-phase proteins (e.g., albumin, prealbumin, transferrin) decrease as the liver reallocates amino acids (Cederholm & Bosaeus, 2024; Gulhar et al., 2024; Sganga et al., 1985).

7.5. Hidden Catabolism: Intracellular Proteins and Cellular Turnover

7.6. Body Composition: Bioimpedance as an Early Warning Tool

7.7. Endocrine Clues: Adrenal Reserve and HPA Flexibility

7.8. Clinical Implication: Interpreting Patterns, Not Points

- Persistent elevation of CRP alongside declining prealbumin or transferrin

- Declining phase angle and lean body mass, even with preserved or rising body weight

- Elevated intracellular enzymes (e.g., ALT, AST, CPK) without clear organ-specific pathology

- Persistent hypercholesterolemia or hyperglycemia despite appropriate dietary and lifestyle interventions

- “What phase of adaptation is this patient in?”

- “What exposures, stressors, or nutritional deficits are sustaining this trade-off—and what interventions could restore metabolic balance?”

7.9. Timeliness and Reversibility: Catching ERM Early

7.10. Toward Resilience-Informed Healthspan Care

- Targeted Dietary support: Emphasize high-quality protein and healthy fats, with controlled and context-specific carbohydrate intake

- Micronutrient repletion: Address subclinical deficiencies in protein and their critical cofactors for metabolic and immune functions such as zinc, selenium, magnesium, and iron

- Exposome reduction: Minimize environmental and dietary stressors through clean air and water, toxin avoidance, and anti-inflammatory, nutrient-dense foods

- Circadian and metabolic tempo optimization: align light exposure, sleep-wake cycles, and feeding-fasting windows to support hormonal and metabolic coherence

- Lifestyle-based resilience building: Encourage regular physical activity, stress reduction techniques, restorative sleep, and social connectedness

- Functional monitoring tools: utilize technologies such as BIA and AI-powered wearables to track recovery and adaptation capacity in real time

8. Conclusion: The Metabolic Cost of Resilience

- Validation of ERM-related biomarker clusters (e.g., patterns of acute phase proteins, mitochondrial stress markers, and metabolic flexibility indicators) to predict risk for sarcopenia, frailty, or chronic disease.

- Prospective trials of resilience-informed nutritional interventions—targeting protein quality, micronutrient cofactors, and circadian alignment—to reverse ERM and improve recovery in high-stress populations.

- Development of ERM staging algorithms based on dynamic, cross-system biomarker trends and clinical phenotypes for early detection and monitoring.

- Exploration of ERM phenotypes in specific clinical contexts, such as long COVID, environmental exposure syndromes, or post-intensive care recovery, where metabolic misallocation is suspected.

- Integration of digital health technologies (e.g., bioimpedance, wearables, AI-based recovery tracking) to monitor real-time adaptation and substrate sufficiency in outpatient or preventive care settings.

Funding

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

Written Consent for publication

Availability of data and material

Code availability

Authors' contributions

Acknowledgments

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

List of Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Term |

| ACE | Adverse Childhood Experiences |

| ACTH | Adrenocorticotropic Hormone |

| ALT | Alanine Transaminase |

| AMPK | AMP-Activated Protein Kinase |

| APP | Acute Phase Proteins |

| AST | Aspartate Transaminase |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| BIA | Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CED | Chronic Energy Deficiency |

| CPK | Creatine Phosphokinase |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| DHEA | Dehydroepiandrosterone |

| DRM | Disease-Related Malnutrition |

| eIF2α | Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2 Alpha |

| ERM | Exposure-Related Malnutrition |

| FGF21 | Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 |

| GADD34 | Growth Arrest and DNA Damage-Inducible Protein 34 |

| GAS | General Adaptation Syndrome |

| GDF15 | Growth Differentiation Factor 15 |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-Alpha |

| HPA axis | Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis |

| IL | Interleukin (e.g., IL-6, IL-13, IL-33) |

| ISR | Integrated Stress Response |

| ISRmt | Mitochondrial Integrated Stress Response |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| M1/M2 | Macrophage Polarization States (Pro-inflammatory / Anti-inflammatory) |

| mTORC1 | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 |

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| NK cells | Natural Killer Cells |

| NCDs | Non-Communicable Diseases |

| NRF2 | Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2–Related Factor 2 |

| OxPhos | Oxidative Phosphorylation |

| POPs | Persistent Organic Pollutants |

| PRR | Pattern Recognition Receptor |

| REDs | Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SAM system | Sympathetic–Adrenal–Medullary System |

| SASP | Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype |

| Treg | Regulatory T Cells |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| UPRmt | Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein Response |

References

- Adams, S. H., Anthony, J. C., Carvajal, R., Chae, L., Khoo, C. S. H., Latulippe, M. E.,…Yan, W. (2020). Perspective: Guiding Principles for the Implementation of Personalized Nutrition Approaches That Benefit Health and Function. Adv Nutr, 11(1), 25-34. [CrossRef]

- Alack, K., Pilat, C., & Krüger K*Shared, a. (2019). Current Knowledge and New Challenges in Exercise Immunology. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Sportmedizin, Volume 70(No. 10), 250-260. [CrossRef]

- Ames, B. N. (2006). Low micronutrient intake may accelerate the degenerative diseases of aging through allocation of scarce micronutrients by triage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 103(47), 17589-17594. [CrossRef]

- Aujla, R. S., Zubair, M., & Patel, R. (2025). Creatine Phosphokinase. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Bar-Ziv, R., Bolas, T., & Dillin, A. (2020). Systemic effects of mitochondrial stress. EMBO reports, 21(6), e50094. [CrossRef]

- Beaudart, C., Dawson, A., Shaw, S. C., Harvey, N. C., Kanis, J. A., Binkley, N.,…Dennison, E. M. (2017). Nutrition and physical activity in the prevention and treatment of sarcopenia: Systematic review. Osteoporos Int, 28(6), 1817-1833. [CrossRef]

- Bobba-Alves, N., Juster, R.-P., & Picard, M. (2022). The energetic cost of allostasis and allostatic load. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 146, 105951. [CrossRef]

- Bobba-Alves, N., Sturm, G., Lin, J., Ware, S. A., Karan, K. R., Monzel, A. S.,…Picard, M. (2023). Cellular allostatic load is linked to increased energy expenditure and accelerated biological aging. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 155, 106322. [CrossRef]

- Branco, M. G., Mateus, C., Capelas, M. L., Pimenta, N., Santos, T., Mäkitie, A.,…Ravasco, P. (2023). Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) for the Assessment of Body Composition in Oncology: A Scoping Review. Nutrients, 15(22), 4792. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/15/22/4792.

- Bresnahan, K. A., & Tanumihardjo, S. A. (2014). Undernutrition, the acute phase response to infection, and its effects on micronutrient status indicators. Adv Nutr, 5(6), 702-711. [CrossRef]

- Cabre, H. E., Moore, S. R., Smith-Ryan, A. E., & Hackney, A. C. (2022). Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): Scientific, Clinical, and Practical Implications for the Female Athlete. Dtsch Z Sportmed, 73(7), 225-234. [CrossRef]

- Cahill, G. F., Jr. (2006). Fuel metabolism in starvation. Annu Rev Nutr, 26, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, E. J., & Agathokleous, E. (2019). Building Biological Shields via Hormesis. Trends Pharmacol Sci, 40(1), 8-10. [CrossRef]

- Careccia, G., Mangiavini, L., & Cirillo, F. (2023). Regulation of Satellite Cells Functions during Skeletal Muscle Regeneration: A Critical Step in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Int J Mol Sci, 25(1). [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, T., & Bosaeus, I. (2024). Malnutrition in Adults. New England Journal of Medicine, 391(2), 155-165. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., & Kahn, C. R. (2024). Insulin. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. [CrossRef]

- Chrousos, G. P. (2009). Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nat Rev Endocrinol, 5(7), 374-381. [CrossRef]

- Costa-Mattioli, M., & Walter, P. (2020). The integrated stress response: From mechanism to disease. Science, 368(6489), eaat5314. [CrossRef]

- Crane, P. A., Wilkinson, G., & Teare, H. (2022). Healthspan versus lifespan: New medicines to close the gap. Nature Aging, 2(11), 984-988. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A. J., Gonzalez, M. C., & Prado, C. M. (2023). Sarcopenia ≠ low muscle mass. European Geriatric Medicine, 14(2), 225-228. [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, R. P., & Finlay, D. K. (2015). Glucose, glycolysis and lymphocyte responses. Mol Immunol, 68(2 Pt C), 513-519. [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. C., Corkins, M. R., Malone, A., Miller, S., Mogensen, K. M., Guenter, P.,…Committee, A. M. (2021). The Use of Visceral Proteins as Nutrition Markers: An ASPEN Position Paper. Nutr Clin Pract, 36(1), 22-28. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y., Li, Z., Yang, L., Li, W., Wang, Y., Kong, Z.,…Zeng, L. (2024). Emerging roles of lactate in acute and chronic inflammation. Cell Communication and Signaling, 22(1), 276. [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C., Garagnani, P., Parini, P., Giuliani, C., & Santoro, A. (2018). Inflammaging: A new immune–metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 14(10), 576-590. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. I., Sørensen, T. I. A., Taubes, G., Lund, J., & Ludwig, D. S. (2024). Trapped fat: Obesity pathogenesis as an intrinsic disorder in metabolic fuel partitioning. Obesity Reviews, n/a(n/a). [CrossRef]

- Fulop, T., Larbi, A., Dupuis, G., Le Page, A., Frost, E. H., Cohen, A. A.,…Franceschi, C. (2018). Immunosenescence and Inflamm-Aging As Two Sides of the Same Coin: Friends or Foes? [Review]. Front Immunol, 8(1960). [CrossRef]

- Gambardella, G., Staiano, L., Moretti, M. N., De Cegli, R., Fagnocchi, L., Di Tullio, G.,…di Bernardo, D. (2020). GADD34 is a modulator of autophagy during starvation. Science Advances, 6(39), eabb0205. [CrossRef]

- Geric, I., Schoors, S., Claes, C., Gressens, P., Verderio, C., Verfaillie, C. M.,…Baes, M. (2019). Metabolic Reprogramming during Microglia Activation. Immunometabolism, 1(1), e190002, Article e190002. [CrossRef]

- Gulhar, R., Ashraf, M. A., & Jialal, I. (2024). Physiology, Acute Phase Reactants. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Herman, J. P. (2013). Neural control of chronic stress adaptation. Front Behav Neurosci, 7, 61. [CrossRef]

- Hetz, C., & Papa, F. R. (2018). The Unfolded Protein Response and Cell Fate Control. Molecular Cell, 69(2), 169-181. [CrossRef]

- Hugh-Jones, P. (1955). DIABETES IN JAMAICA. The Lancet, 266(6896), 891-897. [CrossRef]

- IDF. (2025, 2025 Apr 8). IDF Endorses New Classification of Type 5 Diabetes at World Diabetes Congress. International Diabetes Federation. Retrieved 2025 Apr 18 from https://idf.org/news/new-type-5-diabetes-working-group.

- Johnson, R. J., Sánchez-Lozada, L. G., & Lanaspa, M. A. (2024). The fructose survival hypothesis as a mechanism for unifying the various obesity hypotheses. Obesity, 32(1), 12-22. [CrossRef]

- Kalinkovich, A., & Livshits, G. (2017). Sarcopenic obesity or obese sarcopenia: A cross talk between age-associated adipose tissue and skeletal muscle inflammation as a main mechanism of the pathogenesis. Ageing Res Rev, 35, 200-221. [CrossRef]

- Langston, P. K., & Mathis, D. (2024). Immunological regulation of skeletal muscle adaptation to exercise. Cell Metab. [CrossRef]

- Larabee, C. M., Neely, O. C., & Domingos, A. I. (2020). Obesity: A neuroimmunometabolic perspective. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 16(1), 30-43. [CrossRef]

- Laurent, P., Jolivel, V., Manicki, P., Chiu, L., Contin-Bordes, C., Truchetet, M.-E., & Pradeu, T. (2017). Immune-Mediated Repair: A Matter of Plasticity [Mini Review]. Front Immunol, 8. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Y., Lee, Y. J., Yang, J. H., Kim, C. M., & Choi, W. S. (2014). The Association between Phase Angle of Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis and Survival Time in Advanced Cancer Patients: Preliminary Study. Korean J Fam Med, 35(5), 251-256. [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, S. M., Saudek, V., & O'Rahilly, S. (2020). GDF15: A Hormone Conveying Somatic Distress to the Brain. Endocr Rev, 41(4). [CrossRef]

- Lontchi-Yimagou, E., Dasgupta, R., Anoop, S., Kehlenbrink, S., Koppaka, S., Goyal, A.,…Hawkins, M. (2022). An Atypical Form of Diabetes Among Individuals With Low BMI. Diabetes Care, 45(6), 1428-1437. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, D. S. (2023). Carbohydrate-insulin model: Does the conventional view of obesity reverse cause and effect? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 378(1888), 20220211. [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B. S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiol Rev, 87(3), 873-904. [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B. S., & Wingfield, J. C. (2003). The concept of allostasis in biology and biomedicine. Hormones and Behavior, 43(1), 2-15. [CrossRef]

- Meeusen, R., Watson, P., Hasegawa, H., Roelands, B., & Piacentini, M. F. (2006). Central fatigue: The serotonin hypothesis and beyond. Sports Med, 36(10), 881-909. [CrossRef]

- Metallo, Christian M., & Vander Heiden, Matthew G. (2013). Understanding Metabolic Regulation and Its Influence on Cell Physiology. Molecular Cell, 49(3), 388-398. [CrossRef]

- Monzel, A. S., Levin, M., & Picard, M. (2023). The energetics of cellular life transitions. Life Metabolism, 3(3). [CrossRef]

- Mountjoy, M., Sundgot-Borgen, J. K., Burke, L. M., Ackerman, K. E., Blauwet, C., Constantini, N.,…Budgett, R. (2018). IOC consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update. Br J Sports Med, 52(11), 687-697. [CrossRef]

- Muscaritoli, M., Imbimbo, G., Jager-Wittenaar, H., Cederholm, T., Rothenberg, E., di Girolamo, F. G.,…Molfino, A. (2023). Disease-related malnutrition with inflammation and cachexia. Clin Nutr, 42(8), 1475-1479. [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, K., Yuno, M., Tanaka, K., & Nakamura, T. (2022). High Aspartate Aminotransferase/Alanine Aminotransferase Ratio May Be Associated with All-Cause Mortality in the Elderly: A Retrospective Cohort Study Using Artificial Intelligence and Conventional Analysis. Healthcare (Basel), 10(4). [CrossRef]

- Netea, M. G., Joosten, L. A., Latz, E., Mills, K. H., Natoli, G., Stunnenberg, H. G.,…Xavier, R. J. (2016). Trained immunity: A program of innate immune memory in health and disease. Science, 352(6284), aaf1098. [CrossRef]

- Novoa, I., Zeng, H., Harding, H. P., & Ron, D. (2001). Feedback inhibition of the unfolded protein response by GADD34-mediated dephosphorylation of eIF2alpha. J Cell Biol, 153(5), 1011-1022. [CrossRef]

- Ochando, J., Mulder, W. J. M., Madsen, J. C., Netea, M. G., & Duivenvoorden, R. (2023). Trained immunity — basic concepts and contributions to immunopathology. Nature Reviews Nephrology, 19(1), 23-37. [CrossRef]

- Olcay Güngör, Oya Kıreker Köylü, Tahir Dalkıran, Serkan Kırık, Elif Tepe, Derya Cevizli,…Dilber, C. (2018). Evaluation of blood neuron specific enolase and S-100 beta protein levels in acute mercury toxicity. Trace Elements and Electrolytes, 35(131-136. ). [CrossRef]

- Olenchock, B. A., Rathmell, J. C., & Vander Heiden, M. G. (2017). Biochemical Underpinnings of Immune Cell Metabolic Phenotypes. Immunity, 46(5), 703-713. [CrossRef]

- Pakos-Zebrucka, K., Koryga, I., Mnich, K., Ljujic, M., Samali, A., & Gorman, A. M. (2016). The integrated stress response. EMBO reports, 17(10), 1374-1395. [CrossRef]

- Paulussen, K. J. M., McKenna, C. F., Beals, J. W., Wilund, K. R., Salvador, A. F., & Burd, N. A. (2021). Anabolic Resistance of Muscle Protein Turnover Comes in Various Shapes and Sizes. Front Nutr, 8, 615849. [CrossRef]

- Payea, M. J., Dar, S. A., Anerillas, C., Martindale, J. L., Belair, C., Munk, R.,…Maragkakis, M. (2024). Senescence suppresses the integrated stress response and activates a stress-remodeled secretory phenotype. Molecular Cell, 84(22), 4454-4469.e4457. [CrossRef]

- Peeri, N. C., Chai, W., Cooney, R. V., & Tao, M. H. (2021). Association of serum levels of antioxidant micronutrients with mortality in US adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2002. Public Health Nutr, 24(15), 4859-4868. [CrossRef]

- Picard, M., & Shirihai, O. S. (2022). Mitochondrial signal transduction. Cell Metab, 34(11), 1620-1653. [CrossRef]

- Pizzorno, J. (2020). Thoughts on a Unified Theory of Disease. Integrative medicine (Encinitas, Calif.), 19(6), 8-17.

- Polidori, M. C. (2024). Aging hallmarks, biomarkers, and clocks for personalized medicine: (re)positioning the limelight. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Prisabela, M., Nadhiroh, S. R., & Isaura, E. R. (2023). Characteristics of Pregnant Woman with Chronic Energy Deficiency in Puskesmas Gesang, Lumajang on 2020: Descriptive Analysis. Media Gizi Kesmas, 12(2), 643-648. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y., Rajbanshi, B., Hao, R., Dang, Y., Xu, C., Lu, W.,…Zhang, X. (2025). The dual role of PGAM5 in inflammation. Exp Mol Med, 57(2), 298-311. [CrossRef]

- Ristow, M., & Schmeisser, K. (2014). Mitohormesis: Promoting Health and Lifespan by Increased Levels of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). Dose-Response, 12(2), dose-response.13-035.Ristow. [CrossRef]

- Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers: The acclaimed guide to stress, stress-related diseases, and coping (3rd ed.). Henry Holt.

- Seiler, A., Fagundes, C. P., & Christian, L. M. (2020). The Impact of Everyday Stressors on the Immune System and Health. In A. Choukèr (Ed.), Stress Challenges and Immunity in Space: From Mechanisms to Monitoring and Preventive Strategies (pp. 71-92). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Selye, H. (1950). Stress and the General Adaptation Syndrome. British Medical Journal, 1(4667), 1383-1392. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2038162/.

- Sganga, G., Siegel, J. H., Brown, G., Coleman, B., Wiles, C. E., 3rd, Belzberg, H.,…Placko, R. (1985). Reprioritization of hepatic plasma protein release in trauma and sepsis. Arch Surg, 120(2), 187-199. [CrossRef]

- Shaulson, E. D., Cohen, A. A., & Picard, M. (2024). The brain–body energy conservation model of aging. Nature Aging, 4(10), 1354-1371. [CrossRef]

- Sparkenbaugh, E. M., Saini, Y., Greenwood, K. K., LaPres, J. J., Luyendyk, J. P., Copple, B. L.,…Roth, R. A. (2011). The Role of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α in Acetaminophen Hepatotoxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 338(2), 492-502. [CrossRef]

- Speakman, J. R., & Hall, K. D. (2021). Carbohydrates, insulin, and obesity. Science, 372(6542), 577-578. [CrossRef]

- Straub, R. H. (2017). The brain and immune system prompt energy shortage in chronic inflammation and ageing [Perspective]. Nat Rev Rheumatol, 13, 743–75. [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Baer, M., & Herman, D. (2018). From Epidemiology to Epigenetics: Evidence for the Importance of Nutrition to Optimal Health Development Across the Life Course. In N. Halfon, C. B. Forrest, R. M. Lerner, & E. M. Faustman (Eds.), Handbook of Life Course Health Development (pp. 431-462). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Tsigos, C., & Chrousos, G. P. (2002). Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53(4), 865-871. [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, R., Schymanski, E. L., Barabási, A. L., & Miller, G. W. (2020). The exposome and health: Where chemistry meets biology. Science, 367(6476), 392-396. [CrossRef]

- Vuscan, P., Kischkel, B., Joosten, L. A. B., & Netea, M. G. (2024). Trained immunity: General and emerging concepts. Immunological Reviews, 323(1), 164-185. [CrossRef]

- Walrand, S., Guillet, C., & Boirie, Y. (2021). Nutrition, Protein Turnover and Muscle Mass. In Sarcopenia (pp. 45-62). [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Hong, W., Zhu, H., He, Q., Yang, B., Wang, J., & Weng, Q. (2024). Macrophage senescence in health and diseases. Acta Pharm Sin B, 14(4), 1508-1524. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., & Zhang, G. (2025). The mitochondrial integrated stress response: A novel approach to anti-aging and pro-longevity. Ageing Res Rev, 103, 102603. [CrossRef]

- Warde, K. M., Smith, L. J., & Basham, K. J. (2023). Age-related Changes in the Adrenal Cortex: Insights and Implications. Journal of the Endocrine Society, 7(9), bvad097. [CrossRef]

- Wek, R. C. (2018). Role of eIF2α Kinases in Translational Control and Adaptation to Cellular Stress. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 10(7). [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2025). Noncommunicable diseases. WHO. Retrieved March 25 from https://www.who.int/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases#tab=tab_1.

- Willmann, K., & Moita, L. F. (2024). Physiologic disruption and metabolic reprogramming in infection and sepsis. Cell Metab. [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, R. R. (2006). The underappreciated role of muscle in health and disease. Am J Clin Nutr, 84(3), 475-482. [CrossRef]

- Yiallouris, A., Tsioutis, C., Agapidaki, E., Zafeiri, M., Agouridis, A. P., Ntourakis, D., & Johnson, E. O. (2019). Adrenal Aging and Its Implications on Stress Responsiveness in Humans [Review]. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 10(54). [CrossRef]

- Youle, R. J., & van der Bliek, A. M. (2012). Mitochondrial Fission, Fusion, and Stress. Science, 337(6098), 1062-1065. [CrossRef]

- Yuk, J.-M., Silwal, P., & Jo, E.-K. (2020). Inflammasome and Mitophagy Connection in Health and Disease. Int J Mol Sci, 21(13), 4714. https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/21/13/4714.

- Zera, A. J., & Harshman, L. G. (2001). The Physiology of Life History Trade-Offs in Animals. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 32(Volume 32, 2001), 95-126. [CrossRef]

| System | Primary Adaptive Role Under Stress | Preferred Energy Substrates | Recovery Potential (if Stress Resolves) | Vulnerabilities Under Deficit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroendocrine | Glucose mobilization, survival triage | Gluconeogenesis, lipolysis | Moderate (via HPA feedback and cortisol tapering) | HPA overactivation, insulin resistance |

| Immune | Inflammation, defense coordination | Glycolysis (pro-inflammatory), OXPHOS (resolution) | High (if inflammatory–resolving balance restored) | Chronic inflammation, immune senescence |

| Muscle | Amino acid reservoir, metabolic buffering | Glycogen, fatty acids, protein catabolism | High (if nutrient repletion and anti-inflammatory signaling occur) | Anabolic resistance, sarcopenia |

| Cellular ISR | Proteostasis, autophagy, stress signaling | Internal recycling, selective translation | Moderate to high (if ATP/redox status is restored) | Persistent translation block, proteostasis failure, apoptosis |

| Mitochondria | Energy production, redox balance, mitokine release | OXPHOS, glycolysis, fatty acids | High (if mitophagy and fission/fusion are restored) | ROS overload, mitokine dysfunction |

| Feature | ✔️Homeostasis “Return to Baseline” |

➕Hormesis “Adaptive Overcompensation” |

⚠️Maladaptation “Chronic Dysregulation” |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Availability | Restored baseline levels | Sufficient with transient surplus | Depleted or misallocated |

| Functional Outcome | Functional recovery | Enhanced resilience or capacity | Progressive dysfunction |

| Immune Response | Inflammation resolves | Trained immunity and regulatory tolerance | Chronic inflammation, immune exhaustion |

| Muscle Remodeling | Repair of damaged fibers | Functional hypertrophy, mitochondrial gains | Catabolism, fibrosis, loss of regenerative signaling, sarcopenia |

| ISR Recovery | Reinstated proteostasis | Increased stress resilience, adaptive proteostatic memory | Persistent translation block, apoptosis |

| Mitochondrial Dynamics | Normalized bioenergetics | Improved redox balance, adaptive signaling | ROS overload, mitophagy failure, fragmentation, fission–fusion imbalance |

| Recovery Prerequisites | Energy repletion, stress withdrawal | Surplus energy, time, micronutrient support | Insufficient recovery, chronic demand |

| Feature | DRM | CED | REDs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predominant Affected Populations | Hospitalized or chronically ill patients or elderly patients | Pregnant women, children, low-resource settings | Endurance athletes, dancers, military recruits |

| Typical Onset Pattern | Insi | Gradual under chronic physiological strain (e.g., pregnancy) | Subacute with high training load |

| Primary Triggers | Inflammation, disease burden | Increased physiological need, low intake, low protein quality, micronutrient dilution | Prolonged mismatch between training intensity and caloric intake |

| Common Nutritional Biomarker Patterns | Often abnormal (e.g., prealbumin ↓) | Subclinical changes; may appear normal in standard labs | May have normal BMI, hormonal suppression, low leptin, low T3 |

| Typical Misinterpretation | Mistaken for cachexia or age-related wasting; underrecognized in patients with stable weight but ongoing inflammation | Often overlooked due to normal BMI; perceived as low priority unless accompanied by weight loss or overt signs of undernutrition | Frequently missed due to normal or athletic appearance; symptoms attributed to overtraining, psychological stress, or lifestyle choice |

| Characteristic Clinical Features | Weight loss, immune dysfunction, poor healing | Maternal fatigue, micronutrient depletion, fetal risk, growth restriction | Performance decline, bone loss, menstrual irregularity |

| Response to Nutritional Intervention | Requires nutritional support alongside anti-inflammatory therapy | Improves with energy/nutrient repletion | Requires coordinated refeeding and training load recalibration |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).