1. Introduction

Rice cultivation in Brazil is characterized by the flood irrigation system (SOSBAI, 2022; Sousa et al., 2021). Under these conditions, a series of physical, chemical and biological transformations take place in the soil (Freitas et al., 2024), resulting in a change from an aerobic (oxidized) environment to an anaerobic (reduced) environment (Sousa et al., 2002). The main chemical change that occurs during flooding is the reduction of poorly soluble Fe3+ to highly soluble Fe2+, with a consequent increase in pH to values close to 6.5-7.0 in 3 to 4 weeks (Carmona et al., 2021; Suriyagoda et al., 2017). Manganese (Mn) is another cation whose oxidation-reduction is altered by flooding, changing from Mn+4 to more soluble Mn+2, and significant amounts of Mn2+ begin to accumulate in the exchange complex (Sparrow & Uren, 2014). However, the determination of these exchangeable cations in soil samples after flooding is normally underestimated, since in this reduced condition they are very susceptible to oxidation, especially Fe2+, which is very unstable, causing serious determination errors. The cations Na+, K+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ are not directly involved in the oxidation-reduction reactions and what generally occurs is a displacement of these cations from the exchange sites to the soil solution (Nel et al., 2023). As the pH increases to values above 6.0, almost all of the exchangeable Al will precipitate and disappear from the exchangeable phase (Martins et al., 2020).

The CEC of soils under dryland conditions is composed mainly of the cations K+, Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+ and Al3+ (Nel et al., 2023). However, with the changes caused by flooding, the effective CEC of a soil after three to four weeks of flooding will be composed of K+, Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Mn2+ and Fe2+, with Fe2+ being able to occupy a very significant portion of the exchange complex due to the large amounts of this element that can be reduced during flooding (Sousa et al., 2002). Another change caused by the increase in pH is the increase in variable soil charges or pH-dependent charges. Thus, the effective CEC after flooding is expected to assume values close to those of the potential CEC (pH 7.0) (Barrow & Hartemink, 2023).

The process of reducing Mn and Fe and increasing the concentration of these elements in the soil solution are beneficial for rice, as they increase the pH, the availability of Mn and Fe, displace other cations into the soil solution, and mainly by increasing the availability of phosphorus (Sparrow & Uren, 2014). All these changes favor the growth and development of rice, by increasing the availability of nutrients to plants (Borin et al., 2016; Carlos et al., 2020). However, under certain situations, Fe can reach toxic levels, impairing plant growth and rice productivity (Carmona et al., 2021; Holzschuh et al., 2014).

Fe toxicity in irrigated rice is one of the most important abiotic stresses limiting rice production worldwide (Schmidt et al., 2013). In severe cases, it can cause plant death and reduce rice production up to 100%, depending on the intensity of toxicity and the tolerance of the rice cultivar (Sahrawat, 2004). Predicting the occurrence of Fe toxicity in irrigated rice in each soil is important for the use of measures to minimize this disturbance. To this end, an indicator for this prediction can be the ratio between Fe2+ accumulated after soil flooding and other exchangeable cations in the soil (Ullah et al., 2023). This ratio is based on cation levels after flooding, but the aim is to obtain these data even before rice cultivation (Carmona et al., 2021). However, the simple interpretation of the analysis of soil samples carried out under dryland conditions does not fit with the condition after flooding, given all the transformations caused by it. In order to solve this problem, it may be possible to estimate the cation levels in the flooded soil through soil characteristics that are related to the chemical transformations during flooding, determined in samples under dryland conditions. However, to establish all these relationships, it is necessary to have the amount of Fe2+ accumulated during flooding, but since acquiring this variable is very difficult, obtaining this data via estimation would allow establishing the relationships between before and after flooding and, consequently, a way to predict the occurrence of Fe toxicity (Carmona et al., 2021; Ullah et al., 2023). Thus, the hypothesis of the work is the possibility of estimating, from a sample collected before flooding, the effective CEC after flooding through a linear relationship between the variation of pH before and after flooding with the variation of the effective CEC and CEC pH 7.0, and assigning the difference between this estimated effective CEC and the sum of the cations Ca, Mg, Mn, K and Na to the amount of exchangeable Fe2+ that starts to occupy the exchange sites after flooding. Based on the above, the objective of this work is to estimate the effective CEC after flooding by increasing the soil pH and, subtracting it from the sum of Ca, Mg, Mn, K and Na, to estimate the exchangeable Fe2+ after flooding.

3. Results

The concentrations of Mn and Fe in the solution of the 21 soil samples are presented in

Table 2, before and after flooding. The Mn concentration increased in all soil samples with flooding. On average, it went from 0.03 mmol L

-1 before to 1.12 mmol L

-1 after flooding. The increase in Mn concentration with soil flooding was also observed in a study carried out by Sousa et al. (2002), due to the reduction of Mn

4+ (manganic oxides) to Mn

2+ (manganous oxides) and the consequent release into the soil solution (Sparrow & Uren, 2014).

Soil flooding promoted an increase in the Fe concentration in the soil solution, on average from 0.06 mmol L-1 before to 3.19 mmol L-1 after flooding. Other authors also observed in their works an increase in Fe concentrations with soil flooding, with peak Fe concentration varying between soils (Sousa et al., 2002). The increase in the concentration of this cation in the soil solution is due to the reduction of Fe3+ (ferric oxides) to Fe2+ (ferrous oxides) and the consequent release into the soil solution (Carmona et al., 2021).

Table 2 also shows the pH values before and after a 50-day flooding period. The pH increased with the flooding in all samples. On average, it went from 4.89 before to 6.71 after the flooding. The increase in pH in flooded acidic soils is due to the reduction reactions of oxidized compounds in the soil, which always occur with the consumption of H

+ ions (Ding et al., 2019). The increase in pH promotes the increase of negative charges in the soil (pH-dependent charges), through the dissociation of organic and mineral radicals. In the case of the soils under study, organic matter is the main contributor to these variable soil charges (Ding et al., 2019).

With soil flooding, the pH of acidic soils converges to values close to 7.0, except for soils with low Fe contents (Sousa et al., 2002). An example of this exception may be soil 5, which had a pH of 5.44, well below the average of 6.71, and was the only soil with a pH value after flooding lower than 6.0. The concentrations of both Mn and Fe in the soil solution are low in this soil (

Table 2), that is, as there are few reduction products, soil reduction was probably low and H

+ consumption was small, consequently the pH after flooding was well below that of other soils. Another probable cause may be the low organic C content (unpublished data) causing less soil reduction, resulting in a small increase in pH (Ding et al., 2019).

The optimum pH of the soil solution for rice plants is approximately 6.6 (Ponnamperuma, 1972), since at this pH value the supply of most nutrients is adequate and the concentration of toxic substances is below the levels capable of causing toxicity. The soil solution samples in the present study maintained their pH after flooding close to this optimum value, with the exception of sample 5, which had a pH well below, as already mentioned.

Table 3 presents the data on the concentrations of K, Ca and Mg in the solution of the soil samples before and after flooding. In general, K was little affected by flooding, with an average concentration of 0.20 mmol L

-1 before and 0.24 mmol L

-1 after flooding.

The concentrations of Ca and Mg increased in all samples with flooding (

Table 3), on average going from 1.30 to 5.07 mmol L

-1 and from 0.73 to 2.57 mmol L

-1 after flooding, respectively.

Although the cations K, Ca and Mg are not directly involved in the oxidation-reduction reactions of flooded soils, their kinetics are closely related to the kinetics of Fe and Mn, being displaced from the exchange complex to the soil solution by these cations. Fe, Mn and Ca have similar selectivity for adsorption on the surface of clays (Saeki, et al, 2004), so when there is an increase in Fe or Mn in the solution, the exchange and displacement of Ca from the exchange site to the soil solution will occur concurrantly (Orucoglu et al., 2022).

Table 4 presents the results of the exchangeable cation contents of the soil samples before flooding. There was a wide range of variation in the contents among the soil samples. The K contents ranged from 0.12 to 0.54 cmol

c dm

-3, the Na contents from 0.00 to 1.18 cmol

c dm

-3, the Ca contents from 0.48 to 37.31 cmol

c dm

-3, the Mg contents from 0.10 to 15.53 cmol

c dm

-3, the Mn contents from 0.01 to 0.36 cmol

c dm

-3, the Al contents from 0.10 to 1.74 cmol

c dm

-3 and the H

+Al contents from 2.01 to 8.42 cmol

c dm

-3.

In a study carried out by Silva (2008) with 16 samples of floodplain soils from southern Brazil, K levels ranging from 0.08 to 0.48 cmolc dm-3, Ca levels from 0.60 to 20.80 cmolc dm-3, Mg levels from 0.60 to 9.30 cmolc dm-3 and Al levels from 0.00 to 2.60 cmolc dm-3 were observed. Reis (2008), working with 57 soil samples from floodplains in southern Brazil, observed variations in K levels from 0.03 to 0.75 cmolc dm-3, Na levels from 0.02 to 1.32 cmolc dm-3, Ca levels from 0.00 to 20.40 cmolc dm-3, Mg levels from 0.00 to 8.33 cmolc dm-3and H+Al levels from 1.19 to 16.93 cmolc dm-3. Comparing the results with data in the literature, it is observed that the levels obtained in this work are within the range cited in the literature, except in two soil samples (19 and 21), whose maximum values of Ca and Mg are above the limits observed by Silva (2008) and Reis (2008).

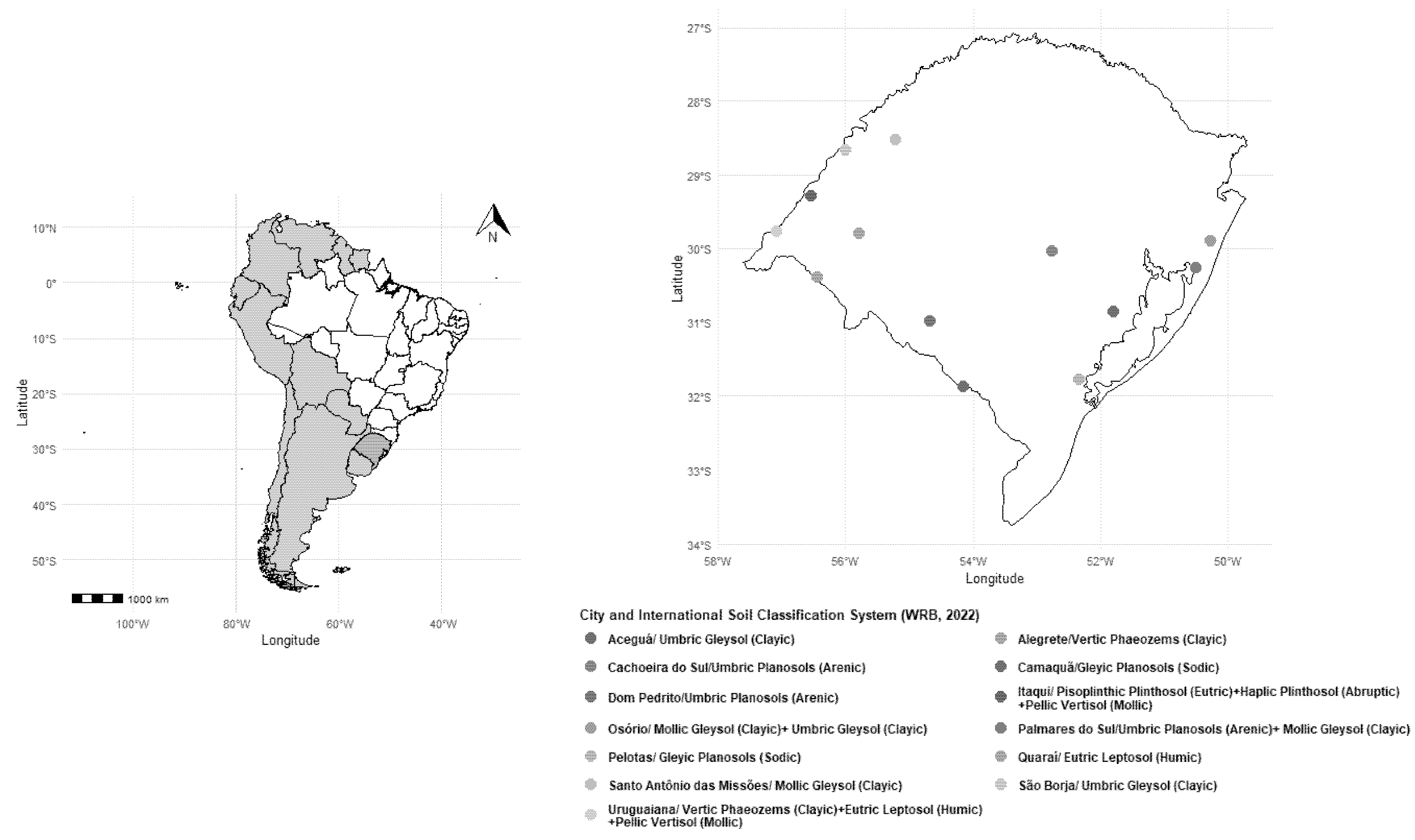

As the floodplain soils used in irrigated rice cultivation in southern Brazil originate from a very wide variety of rocks and sediments associated with environmental factors, soils with very distinct chemical and physical characteristics were formed (Streck et al., 2008).

Table 4 also presents the results of the effective CEC and CEC at pH 7.0 of the 21 soil samples used in the experiment. There was a wide range of variation in the CEC values in the soil samples, both for the effective and for pH 7.0, which is necessary in studies such as this. The values of the effective CEC ranged from 1.27 to 54.43 cmol

c dm

-3, while those of the CEC at pH 7.0 ranged from 2.93 to 56.54 cmol

c dm

-3. In both cases, the CEC was lower in soil 5 and higher in soil 21. Similar results were found by Reis (2008), who observed a range of 3.01 to 42.07 cmol

c dm

-3 of CEC at pH 7.0 in 57 soil samples from southern Brazil.

The lowest CEC values were observed in Planosol samples, while the highest were observed in Gleysols. Planosols generally have a sandy texture and low organic matter content, while Gleysols have a medium to clayey texture with high organic matter content, which gives them a high CEC (Streck et al., 2008).

Table 5 shows the values of exchangeable cations and effective CEC of the 21 soil samples subjected to 50 days of flooding. It should be noted that the exchangeable H content was not determined, since the pH of the soils after flooding was on average 6.7 (

Table 2), at which pH the H is found in precipitated forms. When the soil reaches pH values between 5.5 and 6.0, the exchangeable H is completely neutralized (Martins et al., 2020).

Flooding of the soil did not cause pronounced effects on the exchangeable K contents, which showed small variations both upwards and downwards in the samples, but the average of all soils after flooding remained the same as before flooding, 0.23 cmol

c dm

-3 (

Table 5 and

Table 4). This result is consistent, since K is not directly involved in oxidation-reduction reactions, and since there were no major changes in the concentrations in the soil solution (

Table 3), exchangeable K was not affected.

The exchangeable Na contents behaved similarly to K, presenting small variations both upwards and downwards in the samples, and on average went from 0.45 cmol

c dm

-3 before (

Table 4) to 0.41 cmol

c dm

-3 after flooding (

Table 5), not being as affected by soil reduction.

The Ca and Mg contents decreased in the exchangeable phase with the reduction of the soil due to flooding. As the concentrations of these elements increased in the soil solution with flooding (

Table 3), there was a displacement of these elements to the soil solution, decreasing the values in the exchangeable phase (

Table 5).

The Mn contents in the exchangeable phase increased in all samples with soil reduction. On average, they went from 0.11 cmol

c dm

-3 before flooding (

Table 4) to 1.17 cmol

c dm

-3 after 50 days of flooding (

Table 5). The exchangeable Mn

2+ content is low in most soils, but as flooding promotes an increase in the concentration of this cation in the soil solution, due to the reduction of Mn from manganic to manganous oxides (Sparrow & Uren, 2014), the adsorption of Mn

2+ from the soil solution to the exchangeable phase begins to occur, considerably increasing its quantities.

The exchangeable Fe content after flooding showed wide variation in the samples, ranging from 0.04 to 3.76 cmol

c dm

-3 (

Table 5). In soil under aerobic conditions, Fe does not participate significantly in the exchange complex, due to its low solubility and small quantity in free form, but with soil reduction, Fe changes from valence

3+ to

2+, increasing its solubility and quantity.

The effective CEC of soils after flooding is determined by the sum of the exchangeable contents of K, Na, Ca, Mg, Fe and Mn. The values found varied widely, from 1.34 to 54.25 cmol

c dm

-3 (

Table 5). On average, the CEC was 16.44 cmol

c dm

-3, a value that was below expectations, since on average the effective CEC of samples under rainfed conditions was 15.11 cmol

c dm

-3 and the average CEC at pH 7.0 was 18.85 cmol

c dm

-3 (

Table 4), with a difference of 3.74 cmol

c dm

-3. As the soil pH had an average value of 6.71 after the flooding period (

Table 2), being 1.82 higher than before the flooding and close to pH 7.0, a higher effective CEC was expected after flooding, closer to the CEC pH 7.0.

Considering that after flooding there are no significant concentrations of exchangeable Al

3+ due to the increase in pH and that the concentrations of exchangeable K, Na, Ca and Mg do not change significantly, it is believed that there are no errors in the determination of these cations. Thus, it is expected that the differences may be related to the determination of Mn and Fe, which are the cations that increase greatly with soil reduction. Possibly, the difference between the measured and estimated CEC values are in these cations, that is, they must be underestimated, considering that in the reduced form these elements are not stable, since they oxidize easily in contact with oxygen. Since soils generally have greater amounts of Fe than Mn and because Fe is much more unstable than Mn, most of the difference must be in the determination of this cation.Therefore, it was not possible to test the hypothesis of the study experimentally. Thus, we attempted to correct this possible underestimation of Fe and the consequent effective CEC by estimating the effective CEC after flooding, based on the effective CEC and CEC at pH 7.0 determined in dry soil, and the pH variation before and after flooding, according to equations 1 and 2.

Table 6 presents the values of the effective CEC estimated after flooding, with an average of 18.41 cmol

c dm

-3, 1.97 cmol

c dm

-3 higher than the effective CEC determined after flooding. These values were closer to the CEC determined at pH 7.0, which was 18.85 cmol

c dm

-3 (

Table 4), which is expected since the pH of the solution after flooding was on average 6.7, close to the CEC value of 7.0.

Table 6 also presents the values of exchangeable Fe estimated after flooding. The values were higher than those determined (

Table 5), indicating a certain correction, since the determined values presented possible underestimation by the determination method, as discussed previously.

The cations Fe2+, Mn2+ and Ca2+ have similar selectivity coefficients, that is, there is no adsorption preference in the solid phase between these cations (Saeki et al., 2004). Thus, it is assumed that the molar fraction between these divalent cations in the soil solution is proportional to the percentage they occupy in the exchangeable phase. Therefore, if we compare the molar fractions of these between the soil solution and the fraction in the exchangeable phase, the values should be very similar.

Table 7 presents the molar fractions of the cations in the soil solution and in the exchangeable phase. Comparing the fractions in the soil solution with the fractions in the CEC determined after flooding, the fractions are very similar for Mn and Mg, but there is a discrepancy between the fractions for Ca and Fe (

Table 7). Taking the two methods of determining Fe (soil solution and exchange complex) as a basis, it is possible that in both cases the levels are underestimated. However, it is likely that this underestimation is much smaller in the determination of the solution, considering all the care that is taken at the time of collection to avoid contact of the sample with oxygen in the air. It is also worth mentioning that the quantity in the solution is much smaller than in the exchangeable phase. With this evaluation, it is clear that most of the error is in fact in the exchangeable Fe after flooding, since the fraction in the solution of Mn was very similar to the molar fraction in the exchange complex.

Now comparing the molar fractions in the solution with the fractions estimating the effective CEC and exchangeable Fe (

Table 7), an improvement in the results is noted, where the proportion of Mg, Fe and Mn are equal in the soil solution with the exchangeable phase, confirming the correction of the amounts of Fe underestimated by the determination.