1. Introduction

Pseudorabies virus (PRV), also known as Aujeszky's disease virus (ADV) or suid herpesvirus type 1 (SuHV-1), belongs to the genus Varicellovirus of the subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae with the family Herpesviridae. PRV is an enveloped virus with a large double-stranded linear DNA genome of approximately 150 kb in length and encodes at least 70 proteins [

1,

2]. PRV is the causative agent of Pseudorabies (PR) or Aujeszky’s disease (AD), and it has the capacity to infect a wide variety of wildlife, domestic animals, and livestock, including ruminants, carnivores, and rodents. However, pigs constitute the sole natural reservoir for PRV, and the host to become latent carriers, which can lead to acute infection and great economic losses in the swine industry worldwide, particularly in developing countries [

1,

2]. PRV is a highly neurotropic virus that causes neurological disorders and frequently results in a high rate of mortality in newborn piglets. Conversely, older pigs usually exhibit subclinical symptoms such as respiratory disturbance, malaise and decreased appetite. Furthermore, PRV infections in pregnant sows may lead to breeding obstacles, including stillbirths, abortions, and weakling piglets [

1,

2]. Following the acute stage of infection, PRV can establish a latent infection that persists throughout the life of the infected pig. However, it is noteworthy that latently infected pigs can be re-infected due to the spontaneous reactivation of the latent viral genome or reactivation by stress, a phenomenon that weakens the immune system of latently infected pigs, thereby facilitating a more severe infection [

1,

2].

In China, PR was effectively mitigated through the implementation of extensive vaccination programmers in swine populations using the Bartha-K61 vaccine from the early 1990s until late 2011. However, by the conclusion of 2011, a significant resurgence of PR outbreaks had occurred on numerous Bartha-K61 vaccinated swine farms, rapidly disseminating to various regions across China and resulting in substantial economic losses [

3,

4]. It had been demonstrated that the traditional Bartha-K61 vaccine was incapable of providing complete protection against novel emerging PRV strains in China [

5]. Genetic analysis revealed several mutations in most viral proteins of the PRV variants, including substitutions, insertions and/or deletions. These findings indicated that novel emerging PRV variant strains had begun to circulate among populations of infected pigs in China [

6,

7]. Furthermore, studies have indicated that increased virulence and antigenic variation of the novel PRV mutant strains are the primary cause of the serious spread in China, which could explain why there have been large-scale outbreaks of PRV variant strains in China since late 2011[

6,

7,

8]. Consequently, much attention has been focused on how to prevent and control the recurrence of this disease. Notably, more than 30 clinical cases of PRV infection in humans so far have been reported in China [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Moreover, A human-originated PRV variant strain, designated hSD-1/2019, was successfully isolated from a patient with cerebrospinal fluid in 2019, providing direct evidence of PRV infection in humans, thus classifying the PRV variant strain as an emerging zoonotic pathogen [

15,

16]. However, epidemiological data, genomic characterization, and pathogenicity of the PRV variant strains currently circulating in China, especially in Gansu Province, remain limited. In the present study, a novel PRV variant strain, designated as PRV/Gansu/China/2021, was isolated and identified from a PRV-suspected clinical brain tissue sample from deceased piglets on a Bartha-K61-vaccinated pig farm in Gansu Province, China, in 2021 and further investigation was conducted to ascertain the biological characteristics, genetic features and evolution, and pathogenicity of the strain in mice. Our results suggest that the PRV GS-2021 is a higher virulence variant strain and could have already circulated in Gansu Province of China before 2021.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells, Viruses, Antibodies, and Animals

The propagation or titration of the virus was carried out in Vero cells (SCSP-520, CAS, China) and PK-15 cells (CCL-33, ATCC, USA) with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (11995073, Gibco, China) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (10091148, Gibco, New Zealand) at 37 ◦C in 5 % CO2. The PRV vaccine strain Bartha-K61 was isolated from a commercial vaccine and used as a control virus, while brain tissue from specific-pathogen-free (SPF) piglets used as a negative control. The primary antibodies employed in this study were rabbit anti-pseudorabies virus gB antiserum (PSRVGB11-S, Alpha Diagnostic International, USA) and rabbit anti-pseudorabies virus antibody (ab3534, Abcam, USA). The secondary antibodies employed were goat anti-rabbit IgG alexa fluor®488 (H+L) (GB25303, Servicebio, China) and goat anti-rabbit IgG alexa fluor®594 (H+L) (GB28301, Servicebio, China). Adult BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks, 16–20 g body weight) from the Animal Experimental Center of the Lanzhou Veterinary Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

2.2. Clinical Sample Collection and Virus Detection

Clinical brain samples were obtained from PRV-suspected dead piglets on a Bartha-K61-vaccinated pig farm in Gansu Province, China, in 2021. The brain samples were then homogenized in DMEM at 4 °C, after which the DNA was extracted from the tissue homogenate using a Viral RNA/DNA Extraction Kit (9766, TaKaRa, Japan). The primers for the partial gB and gE gene fragments of PRV were designed according to the PRV gene sequence on GenBank (GenBank accession number: KP722022). The amplified fragments of the target genes were 282 bp and 258 bp. The extracted DNA samples were identified with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using PRV gB and gE-specific pairs primers (

Table 1). The PCR products were then subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm their identity.

2.3. Viral Isolation and Identification

PRV PCR gB and gE-positive homogenates were treated with antibiotics and subjected to a centrifugation process at 5000 g/min for 15 min at 4 °C. Subsequently, the resultant filtrate was filtered through a 0.45-µm filter (0000240486, Merck Millipore, Germany) and inoculated into a monolayer of Vero cells. The cells were then incubated in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) (11095080, Gibco, USA) with 1% FBS in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. The presence of a cytopathic effect (CPE) was examined daily, and the observation of cell morphology and the anchorage-dependent rate were recorded using a microscope. At 85-95% CPE, the Vero cells were subjected to freeze-thaw cycles with the culture medium, after which the cell culture medium was collected. Following amplification, cultivation and six rounds of plaque purification, the virus was identified using PCR and Sanger sequencing, indirect immunofluorescent assay (IFA) and transmission electron microscope (TEM) system HT7800 (Hitachi, Japan).

2.4. Plaque Assay and Plaque Sizes Determination

Vero cells were seeded in 12-well plates, after which a serial 10-fold dilution of the virus was added to the cells. Following a one-hour incubation period, the cells were washed three times with PBS and overlaid with 0.75% carboxy methyl cellulose (M352, Fisher Scientific, USA) in DMEM medium containing 2% FBS. The plates were then incubated at 37°C for 2–3 days until visible plaques formed. The cells were then fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde (252549, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and then stained with 500 μl of crystal violet (C0775, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The plaque-forming units (PFU) of the isolated PRV GS-2021 strain were then calculated by plaque assay. Fifty plaques of each virus were randomly selected, and their diameters were measured using ImageJ software. The relative diameter of the plaque was then calculated as the product of the diameter of the PRV GS-2021 strain divided by those of the Bartha-K61 strain.

2.5. One-Step Growth Curve of the PRV GS-2021 Strain

Vero cell monolayers in 12-well plates were infected with the virus at an MOI of 1. Following incubation at 37°C for 1 h, the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 2% FBS. The cells and the remaining fluid were harvested at 6-, 12-, 24-, 36-, and 48-hour post-infection (hpi) and stored in aliquots at −80°C. Following three freeze-thaw cycles, the virus was tittered by the plaque formation assay in Vero cells.

2.6. Amplification and Sequencing of gB, gC, gD, and gE Genes of the PRV GS-2021 Strain

The complete gB, gC, gD, and gE genes of PRV strain were amplified by PCR through specific primers (

Table 1). The PCR reaction was conducted in the volume of 100 μl containing 20 ng of extracted DNA, 20 μl 5 × PrimerSTAR GXL Buffer, 2 μl PrimeSTAR GXL DNA polymerase (R050A, TaKaRa, China), 8 μL 2.5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 0.25 μM of each primer, add Nuclease-free water supplement to 100 μl. Thermal cycling parameters were 95 ℃ for 4 sec, then 35 cycles of denaturation at 98 ℃ for 10 sec, annealing at 55 ℃ for 10 sec, and extension at 68 ℃ for 3 min 20 sec, followed by final extension at 72 ℃ for 10 min. The purified PCR products were connected to the pJET1.2 vector with the Clone JET PCR Cloning Kit (K1231, Thermo Scientific, USA) and verified by sequencing to obtain the final assembly results.

2.7. Complete Genome Sequencing of the PRV GS-2021 Strain

The whole-genome of the purified PRV GS-2021 strain was sequenced through next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology on PE150 platform with a high-throughput the Illumina Nova 6000 (Magigen Biotech, Guangzhou, China). To assemble the genome, reads were mapped to the reference genome (GenBank accession number: KP722022) and the assembled whole genomic sequence.

2.8. Phylogenetic Analyses of the PRV GS-2021 Strain

Forty-one genome sequences of PRV representing wild strains or vaccine strains from different endemic countries were obtained from GenBank (

Table 1). The sequence was compared to those of viral strains from different endemic countries. The sequences alignment of the nucleic acid and amino acid sequences were conducted by MegAlign module in DNASTAR Lasergene 7 software. Phylogenetic trees were also calculated using the maximum-likelihood method of the MEGA-X software based on the General-Time-Reversible model for the gB gene sequences, the General-Time-Reversible with Invariant Sites Substitution model for the gC gene sequences, the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano with Invariant Sites substitution model for the gD gene sequences, the General-Time-Reversible model for the gE gene sequences, and the General-Time-Reversible with Gamma Distribution Substitution model for the complete genomic sequences, and bootstrap values were calculated with 1000 replicates.

Table 2.

PRV reference strains in this study.

Table 2.

PRV reference strains in this study.

| Strain |

Accession Number |

Genotype (I/IIa/IIb) |

Country |

Species |

Isolate Date |

| TJ |

KJ789182 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2012 |

| ZJ01 |

KM061380 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2012 |

| HNX |

KM189912 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2012 |

| HNB |

KM189914 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2012 |

| HeN1 |

KP098534 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2012 |

| JS-2012 |

KP257591 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2012 |

| DX |

OK338076 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2012 |

| HLJ8 |

KT824771 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2013 |

| GD-YH |

MT197597 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2014 |

| HN1201 |

KP722022 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2015 |

| XJ |

MW893682 |

IIb |

China |

Dog |

2015 |

| JS-XJ5 |

OP512542 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2016 |

| JX |

MK806387 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2016 |

| HeNZM |

MT775883 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2017 |

| HeNLH |

MT775883 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2017 |

| JSY13 |

MT157263 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2018 |

| HuBXY |

MT468549 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2018 |

| FJ |

OP727803 |

IIb |

China |

Tiger |

2018 |

| FJ |

MW286330 |

IIb |

China |

wine |

2019 |

| SX1910 |

OL606749 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2019 |

| hSD-1 |

MT468550 |

IIb |

China |

Human |

2019 |

| SD18 |

MT949536 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2020 |

| GD |

OK338076 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2020 |

| JM |

OK338077 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2021 |

| CD22 |

OR666765 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2022 |

| HLJPRVJ |

OR365764 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2023 |

| DCD-1 |

OL639029 |

IIb |

China |

Swine |

2017 |

| HLJ-2013 |

MK080279 |

IIa |

China |

Swine |

2013 |

| GXGG |

OP605538 |

IIa |

China |

Swine |

2016 |

| HuB17 |

MT949537 |

IIa |

China |

Swine |

2020 |

| JS-2020 |

OR271601 |

IIa |

China |

Swine |

2020 |

| SC |

KT809429 |

IIa |

China |

Swine |

1986 |

| Ea |

KU315430 |

IIa |

China |

Swine |

1990 |

| LA |

KU552118 |

IIa |

China |

Swine |

1997 |

| Fa |

KM189913 |

IIa |

China |

Swine |

2012 |

| MY-1 |

AP018925 |

IIa |

Japan |

Swine |

2015 |

| Kolchis |

KT983811 |

I |

Greece |

Tiger |

2010 |

| Bartha |

JF797217 |

I |

Hungary |

Swine |

1960 |

| Kaplan |

JF797218 |

I |

Hungary |

Swine |

2011 |

| Becker |

JF797219 |

I |

USA |

Swine |

1967 |

| NIA3 |

KU900059 |

I |

UK |

Swine |

2016 |

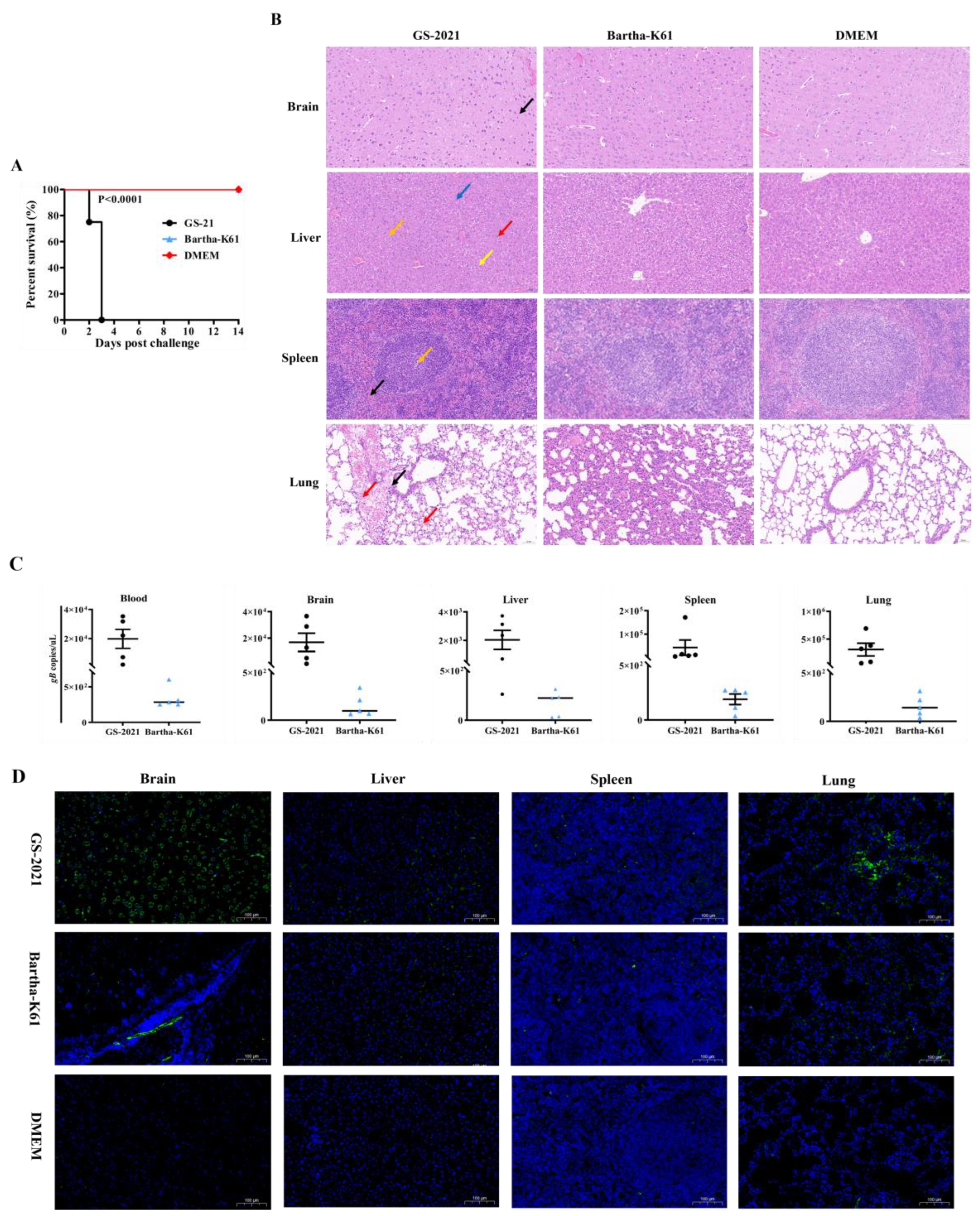

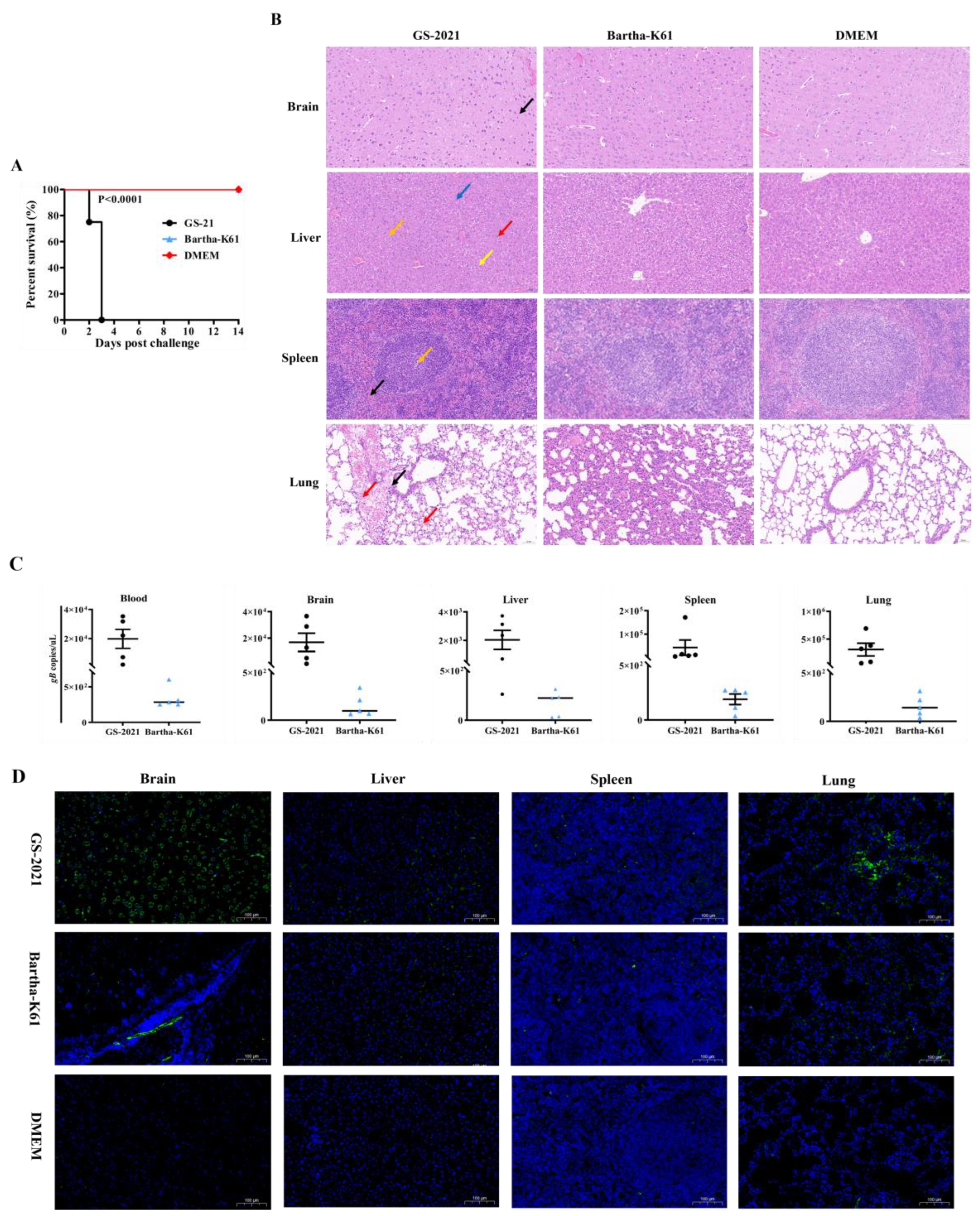

2.9. Challenge of Mice with the PRV GS-2021 Strain

For the pathogenicity of the PRV GS-2021 strain, 24 six-week-old specific-pathogen-free (SPF) BALB/c mice were intranasally (I.N.) injected with 10

4, 10

3, and 10

2 PFU of the variant strain in 10 µl DMEM. At the same time, 32 mice were designated as controls and injected with 10

6, 10

5, and 10

4 PFU of the Bartha-K61 strain and equivalent volume of DMEM. After inoculation, the mice were observed each day for clinical symptoms and death, and lethal dose (LD50) of the virus strains were calculated by the Spearman-Karber method. Liver, spleen, lung, brain and/or blood were collected from the GS-2021 and Bartha-K61-infected mice at 3rd day post-infection for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and IFA, and the virus was detected using gB-speciffc TaqMan quantitative PCR (

Table 1).

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean from 3 independent assays. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 software. The significance of differences between groups was evaluated using a student’s t-test or 2-way analysis of variance. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant: ∗, p<0.05; ∗∗, p<0.01; ∗∗∗, p<0.001, ∗∗∗∗, p<0.0001.

4. Discussion

PRV is a widely spread, highly pathogenic virus that infects multiple domestic and wild animals, and humans. The different PRV virus isolated strains the exhibited varied virulence and biological characteristics, although it still has only one strain type. Since late 2011, several emerging PRV variants have been identified in Bartha-K61-vaccinated pig farms, and then the variant strain rapidly spread to most regions of China and caused significant economic losses to the swine industry in China [

3,

4,

5,

6]. When compared to the foreign and Chinese classical PRV strains, the PRV variant strains shown higher virulence and pathogenicity and the Bartha-K61 vaccine strain fails to provide effective protection [

3,

4,

5]. From 2012 to 2021, some reports showed that there was a high risk of the variant PRV strains substantial epidemic and the need for continuous monitoring [

6,

7,

8]. Therefore, further understanding the biological and genetic characteristics of the prevalent PRV variant strains are important for preventing and controlling PR in China. However, it has always been debated whether the PRV variant strains currently persisting in Gansu Province of China, and its biological characteristics, genetic features, evolutionary relationship and pathogenicity are still unknown.

In the current study, a novel emerging field PRV variant strain called PRV/Gansu/China/2021 (PRV GS-2021) was successfully isolated and identified from the PRV-suspected clinical brain tissue sample of the dead piglets in a conventional Bartha-K61-vaccinated pig farm in Gansu Province of China, 2021, suggesting the PRV variant strain was already circulating in Gansu Province in China before 2021. Moreover, one-step growth curves revealed that the PRV isolated variant strain had similar growth characteristics with Bartha-K61 vaccine strains in vitro, but it grew to high titers in Vero cells. In particular, the PRV GS-2021 strain propagated slightly slower than the Bartha-K61 in PK-15 cells, suggesting the Bartha-K61 strain has a better ability to adapt to this cell line. However, the plaque diameter of the PRV GS-2021 strain was significantly bigger than that of Bartha-K61 in Vero cells. The results showed that the PRV GS-2021 strain had similar biological characteristics with previously isolated PRV variant strains. It is believed that several PRV infection cases in Gansu province of China in recent years were also caused by PRV variant strains, including the PRV GS-2021 variant strain.

At present, PRV strains prevalent worldwide are classified into clades I and II according to the phylogenetic and epidemiologic features [

7]. Clades I mainly contain classical PRV strains from most regions of Europe and America, whereas clades II contain classical and variant PRV strains and mainly prevalent in China [

7]. The variant PRV strains are currently further classified into two sub-clades: Clades IIa, also known as classical PRV strains, which were more common before 2011 and Clades IIb, also known as novel PRV variants, which were first observed in late 2011 and since then have been dominant in China [

7]. We found that the PRV GS-2021 strain belongs to clade II and was closely related to the variant strains in China (clade IIb) based on the gB, gC, gD, and gE genes sequences and the complete genome, respectively. As of now, it is believed that clade IIb remains the predominant epidemic clade affecting substantial economic losses in the pig industry in China, including Gansu province. Meanwhile, we found PRV GS-2021 strain showed high homology with clades II, including Chinese PRV variant strains and variant PRV strains, but it showed low homology with clades I, including Bartha-K61 vaccine strain, based on the nucleotide and amino acid sequence of gB, gC, gD, and gE genes and complete genome sequences of PRV. It is well known that the PRV gB, gC and gD proteins are the major immunogenetic antigens that can induce neutralizing antibody production [

17,

18,

19]. Therefore, these results provided a possible explanation for why the Bartha-K61 vaccine strain provides only partial protection for PRV variants infection. Interestingly, two Aspartate (Asp) insertions are detected at sites 48 and 497 in the gE protein of the PRV Chinese variant strains, including the PRV GS-2021 strain, one Asp insertions are detected at sites 48 in the gE protein of the Chinese classical PRV strains, but Asp insertions are not discovered at sites 48 and 497 in the gE protein of the classical PRV strains in other countries, which are consistent with previously has been reported [

4,

5,

20]. However, glutamate (Glu) is replaced by glycine (Gly) at position 91 only in the gE protein of the PRV GS-2021 strain that increased hydrophobicity of the gE protein. These results suggest that the insertion and/or substitution events in the gE protein of the PRV variants are not coincidental phenomenon, and that may be related to the host’s immune pressure from the Bartha-K6 vaccine strain and may cause changes in pathogenicity and antigen characteristics of the PRV variant strains, including the PRV GS-2021 strain. Recently, several natural recombinant PRV variant strains were isolated and identified on Bartha-K61 vaccinated-pig farm and the natural recombination events maybe occurred in between different PRV genotypes or between wild-type strains and vaccine, although the recombination events were not detected in the PRV GS-2021 strain. Therefore, these results further explained that why the Bartha-K6 vaccine strain provides ineffective protection against the PRV variant strains, and it is necessary to continuously monitor the epidemiological trend and genetic evolution of PRV in China.

At the same time, it is interesting that the PRV GS-2021 strain clustered with two PRV variant strains named PRV/Xinjiang/China/2015 and PRV/Fujian/China/2018 from dog and tiger, respectively. Of note, more interspecies transmission events were observed with clade IIb PRV, including foxes, sheep, minks, raccoons and bovine, in recent years [

1,

2,

6,

7,

21]. Importantly, a Chinese PRV variant strain called PRV/hSD-1/China/2019 was isolated from an acute human encephalitis case in 2019 and can effectively infect human cells and is genetically closest to those PRV variant strains currently circulating in pigs in China [

15,

16]. Besides, since 2017, some reports shown that PRV might infect humans through detection of nucleic acids for PRV by PCR and metagenomic next-generation sequencing or PRV-gE/gB specific antibody by ELISA in China [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Moreover, it was previously reported that PRV gD has ability to bind human and swine-origin nectin-1 receptor with similar binding affinity to initiate virus entry into host cells [

1,

2]. Therefore, these findings largely supported the close phylogenetic relationship and similar etiological characteristics of the PRV GS-2021 and hSD-1/2019 with other variant strains, suggesting the PRV variant strain is an emerging zoonotic pathogen that can infect humans in particular conditions and further implying the great risk of the PRV variant strains transmission from pigs to other animals, pigs to humans, humans to other animals or humans to humans. However, more information regarding the more PRV variant strains derived from human infection cases requires further investigation. For example, whether the different PRV strains have the different virulence and pathogenicity in humans and whether the current vaccines or antivirus drugs are safe and effective enough for humans to prevent novel PRV variants infections? And whether there is a correlation between PRV human infection cases and PRV infection level in pigs? Alternatively, whether the PRV GS-2021 strain can cross the species barrier and be transmitted to humans is unknown.

Furthermore, the pathogenicity of PRV GS-2021 strain was evaluated in mice in this study. All the infected mice died on the 3rd day, and typical PRV-caused symptoms were observed, when infected with 10

4 and 10

3 PFU of the PRV GS-2021. Even if infected with 10

2 PFU of the PRV GS-2021, three mice have only died on the 5th day after infection. In contrast, the all mice infected with 10

4 PFU Bartha-K61 vaccine strain exhibited normal behavior at 5th day post-infection, and did not cause the death of all mice at end of experiment at 14th day, although one and five mice died at 14th day post-inoculation in the infection dose of 10

6 and 10

5 PFU, respectively. In addition, the LD50 of the PRV GS-2021 strain is significantly lower than that of Bartha-K61 vaccine strain, which have also been reported in a previous study [

22,

23,

24], indicating the PRV GS-2021 could a higher virulence variant strain. PRV DNA and antigens-specific fluorescence signals were further detected in different tissue samples from infected mice with 104 PFU of the PRV GS-2021 within 3 days post-infection. Moreover, the PRV GS-2021 strain infection in mice leads to encephalitis in brain including meningeal congestion, hemorrhage, edema and local necrosis, and multiple lesion sites such as, apoptosis, congestion, lymphocytes infiltrating in the live, spleen or lung, were observed by histopathological examination, suggested that the multiple organ damage with PRV infection may be the main cause of death in these mice. About the underlying mechanism involving multiple organ damage, we speculate that a break begins in the site of PRV infection, where the virus will replicate and then disseminate via the lymphatics and viraemia occurs when virus is released into the bloodstream, which then permits infection of the lung, spleen, brain and other organs and the virus replicates uncontrolled, the mice suffer multiple organ damage and most of them die. Notably, histopathologic examinations were normal in all tissues of the Bartha-K61 vaccine strain infected mice, which may be related to the infection route, dose and time, the virulence of the virus strain, and the age of animal model. Herein, we further demonstrated that the PRV GS-2021 strain is a higher virulence variant strain. However, the pathogenicity of the PRV GS-2021 strain and other different strains will be better evaluated in other animals, including pigs, bovine, sheep, and rhesus monkeys, in future experiments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. and Z.J.; methodology, X.H., H.Y., P.J., G.C. and Y.F.; software, X.H., P.J. and G.C.; validation, X.H. and H.Y.; formal analysis, X.H.; investigation, X.H., P.J., G.C. and Y.F.; data curation, X.H.; writing—original draft preparation, X.H.; writing—review and editing, X.H., P.J., Y.W. and Z.J.; visualization, X.H.; supervision, Y.W. and Z.J.; project administration, X.H. and H.Y; funding acquisition, X.H. and H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Detection of the PRV gB or gE genes in clinical brain samples by PCR. (A) Amplified PCR product of partial PRV gB gene (258 bp). (B) Amplified PCR product of partial PRV gE gene (282 bp). Negative sample from a specific-pathogen-free (SPF) piglet used as negative control and Bartha-K61 used as positive control.

Figure 1.

Detection of the PRV gB or gE genes in clinical brain samples by PCR. (A) Amplified PCR product of partial PRV gB gene (258 bp). (B) Amplified PCR product of partial PRV gE gene (282 bp). Negative sample from a specific-pathogen-free (SPF) piglet used as negative control and Bartha-K61 used as positive control.

Figure 2.

Isolation and identification of PRV GS-2021 strain. (A) The cytopathic effect (CPE) of Vero cells caused by GS-2021. The CPE in Bartha-K61-infected Vero cells was considered as positive control (left panels). Indirect immunofluorescence assay detection of gB (green) protein in GS-2021 or Bartha-K61-challenged Vero cells, and the nucleus was stained with DAPI (right panels). (B) Viral particles in Vero cells (top panel) or purified virus (bottom panel) of GS-2021 and Bartha-K61 under the transmission electron microscope. (C) PCR amplification of PRV gC (1605 bp) and gE (1786 bp) fragments from passage 6 cultures of GS-2021-inoculated Vero cells. Bartha-K61 was positive control and DMEM was negative control.

Figure 2.

Isolation and identification of PRV GS-2021 strain. (A) The cytopathic effect (CPE) of Vero cells caused by GS-2021. The CPE in Bartha-K61-infected Vero cells was considered as positive control (left panels). Indirect immunofluorescence assay detection of gB (green) protein in GS-2021 or Bartha-K61-challenged Vero cells, and the nucleus was stained with DAPI (right panels). (B) Viral particles in Vero cells (top panel) or purified virus (bottom panel) of GS-2021 and Bartha-K61 under the transmission electron microscope. (C) PCR amplification of PRV gC (1605 bp) and gE (1786 bp) fragments from passage 6 cultures of GS-2021-inoculated Vero cells. Bartha-K61 was positive control and DMEM was negative control.

Figure 3.

Biological characteristics of the PRV GS-2021 strain in vitro. (A) Plaque formation in Vero cells infected by the GS-2021 and Bartha-K61. (B) The relative plaque size of each virus was normalized to that of Bartha-K61. Significant differences were considered: **P <0.01. (C, D) One-step growth curves of the two PRV strains in Vero cells and PK-15 cells at an MOI of 1, respectively, and the viral titers were determined in Vero cells by plaque assay method.

Figure 3.

Biological characteristics of the PRV GS-2021 strain in vitro. (A) Plaque formation in Vero cells infected by the GS-2021 and Bartha-K61. (B) The relative plaque size of each virus was normalized to that of Bartha-K61. Significant differences were considered: **P <0.01. (C, D) One-step growth curves of the two PRV strains in Vero cells and PK-15 cells at an MOI of 1, respectively, and the viral titers were determined in Vero cells by plaque assay method.

Figure 4.

Comparative sequence alignment of PRV gE proteins. 42 gE amino acid sequences of the PRV strains with complete genome sequences are available in GenBank and were compared using DNASTAR Lasergene 7 software and the sequences were aligned using the Clustal W method.

Figure 4.

Comparative sequence alignment of PRV gE proteins. 42 gE amino acid sequences of the PRV strains with complete genome sequences are available in GenBank and were compared using DNASTAR Lasergene 7 software and the sequences were aligned using the Clustal W method.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic analysis of the PRV strains. (A) Phylogenetic tree based on complete genomic nucleotide sequences. (B-E) Phylogenetic tree based on the nucleotide sequences of gB, gC, gD, and gE genes. Phylogenetic trees were constructed by using MEGA-X software with the ML method and bootstrapping with 1,000 replicates was performed to determine the percentage reliability for each internal node.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic analysis of the PRV strains. (A) Phylogenetic tree based on complete genomic nucleotide sequences. (B-E) Phylogenetic tree based on the nucleotide sequences of gB, gC, gD, and gE genes. Phylogenetic trees were constructed by using MEGA-X software with the ML method and bootstrapping with 1,000 replicates was performed to determine the percentage reliability for each internal node.

Figure 6.

Pathogenicity of the PRV GS-2021 and Bartha-K61 strain in mice. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice challenged with 104 PFU of GS-2021 and Bartha-K61 by intranasal routes (n=8 in each group). (B) Histopathological changes in different tissues of mice infected with GS-2021. Paraffin sections of brain, liver, spleen, and lung tissues from control, 104 PFU GS-2021, and 104 PFU Bartha-K61 groups were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (n=3 in each group). Infiltration of inflammatory cells (black arrows), hemorrhage (red arrows), local necrosis (orange arrows), vacuoles in the cytoplasm (yellow arrows), cell swelling and cytoplasm vacuolar (blue arrows). (C) PRV gB gene copies in blood, brain, liver, lung, and spleen samples of the mice intranasally challenged by GS-2021 and Bartha-K61, determined by gB-specific TaqMan real-time PCR. Each dot represents 1 mouse, and the data were collected and presented as mean ± SEM from 5 mice in each group. (D) Identification of viral particles in brain, liver, lung, and spleen tissues by IFA analysis (n=3 in each group). Anti-PRV Polyclonal antibody was used as the primary antibody, and goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor®488 (H+L) was used as the secondary antibody, and the nucleus was stained with DAPI.

Figure 6.

Pathogenicity of the PRV GS-2021 and Bartha-K61 strain in mice. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice challenged with 104 PFU of GS-2021 and Bartha-K61 by intranasal routes (n=8 in each group). (B) Histopathological changes in different tissues of mice infected with GS-2021. Paraffin sections of brain, liver, spleen, and lung tissues from control, 104 PFU GS-2021, and 104 PFU Bartha-K61 groups were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (n=3 in each group). Infiltration of inflammatory cells (black arrows), hemorrhage (red arrows), local necrosis (orange arrows), vacuoles in the cytoplasm (yellow arrows), cell swelling and cytoplasm vacuolar (blue arrows). (C) PRV gB gene copies in blood, brain, liver, lung, and spleen samples of the mice intranasally challenged by GS-2021 and Bartha-K61, determined by gB-specific TaqMan real-time PCR. Each dot represents 1 mouse, and the data were collected and presented as mean ± SEM from 5 mice in each group. (D) Identification of viral particles in brain, liver, lung, and spleen tissues by IFA analysis (n=3 in each group). Anti-PRV Polyclonal antibody was used as the primary antibody, and goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor®488 (H+L) was used as the secondary antibody, and the nucleus was stained with DAPI.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study.

| Reference Sequence |

|

Gene |

Primer Sequence (5' - 3') |

Length |

KP257591

KP257591

KP257591

KP257591

KP257591

KP257591

KP257591

|

|

gB

gC

gD

gE

gE

gB

gB

|

TGTACCTGACCTACGAGGCGTCATG

GTGGGAGCCGTCACACGCGCCAGC

TGTGTGCCACTAGCATTAAATCCGTT GTTCAACGCGCGGTCGTTTATTGAT

ATACACTCACCTGCCAGCGCCATG

ACCATCATCATCGACGCCGGTACT

GTTGAGACCATGCGGCCCTTTCT

GGACCGGTTCTCCCGGTATTTAAG

TGCCCACGCACGAGGACTACTACG

CGCCATAGTTGGGTCCATTCGTCAC

TGCAGAACAAGGACCGCACCCTGT

GCGAGATGAGGAGCTCGTTGTCGT

AAGTTCAAGGCCCACATCT

TGAAGCGGTTCGTGATGG

FAM-CAAGAACGTCATCGTCACGACCG-BHQ |

2818 bp

1605 bp

1262 bp

1786 bp

258 bp

282 bp

88 bp

|

Table 3.

PRV reference strains in this study.

Table 3.

PRV reference strains in this study.

| Strain |

Complete Genome |

T(%) |

C(%) |

A(%) |

G(%) |

G+C(%) |

A+T(%) |

TJ

ZJ01 |

143642 |

13.27 |

36.94 |

13.10 |

36.69 |

73.63 |

26.37 |

| 141028 |

13.20 |

36.97 |

13.06 |

36.76 |

73.74 |

26.26 |

HNX

HNB |

142294 |

13.30 |

36.82 |

13.14 |

36.74 |

73.56 |

26.44 |

| 142255 |

13.27 |

36.87 |

13.12 |

36.74 |

73.61 |

26.39 |

| HeN1 |

141803 |

13.26 |

36.96 |

13.05 |

36.73 |

73.69 |

26.31 |

| JS-2012 |

145312 |

13.29 |

36.78 |

13.21 |

36.73 |

73.50 |

26.50 |

| DX |

143754 |

13.27 |

36.83 |

13.14 |

36.76 |

73.59 |

26.41 |

| HLJ8 |

142298 |

13.22 |

36.91 |

13.08 |

36.79 |

73.70 |

26.30 |

| GD-YH |

146012 |

13.17 |

36.83 |

13.07 |

36.93 |

73.76 |

26.24 |

| HN1201 |

144173 |

13.27 |

36.81 |

13.18 |

36.73 |

73.54 |

26.46 |

| XJ |

144483 |

13.28 |

36.89 |

13.13 |

36.71 |

73.60 |

26.40 |

| JS-XJ5 |

141955 |

13.22 |

37.05 |

12.99 |

36.75 |

73.79 |

26.21 |

| JX |

143156 |

13.32 |

36.89 |

13.12 |

36.68 |

73.57 |

26.43 |

| HeNZM |

144235 |

13.33 |

36.61 |

13.09 |

36.98 |

73.58 |

26.42 |

| HeNLH |

143254 |

13.21 |

37.04 |

13.01 |

36.74 |

73.78 |

26.22 |

| JSY13 |

143452 |

13.17 |

36.98 |

13.01 |

3684 |

73.82 |

26.18 |

| HuBXY |

143859 |

13.22 |

36.83 |

13.04 |

36.92 |

73.75 |

26.25 |

| FJ |

144795 |

13.23 |

36.79 |

13.14 |

36.84 |

73.63 |

26.37 |

| FJ |

142763 |

13.19 |

36.86 |

13.43 |

36.52 |

73.38 |

26.62 |

| SX1910 |

143703 |

13.23 |

36.78 |

13.14 |

36.84 |

73.62 |

26.38 |

| hSD-1 |

143236 |

13.25 |

36.88 |

13.12 |

36.75 |

73.63 |

26.37 |

| SD18 |

143905 |

13.24 |

36.87 |

13.10 |

36.79 |

73.66 |

26.34 |

| GD |

143418 |

13.27 |

36.93 |

13.10 |

36.70 |

73.63 |

26.37 |

| JM |

144046 |

13.19 |

36.92 |

13.06 |

36.83 |

73.75 |

26.25 |

| CD22 |

142472 |

13.23 |

37.05 |

13.03 |

36.69 |

73.74 |

26.26 |

| HLJPRVJ |

143520 |

13.29 |

36.93 |

13.10 |

36.69 |

73.61 |

26.39 |

| DCD-1 |

143218 |

13.20 |

36.93 |

13.07 |

36.81 |

73.73 |

26.27 |

| HLJ-2013 |

142560 |

13.23 |

36.95 |

13.09 |

36.73 |

73.67 |

26.33 |

| GXGG |

142288 |

13.25 |

36.89 |

13.08 |

36.77 |

73.67 |

26.33 |

| HuB17 |

141631 |

13.19 |

37.06 |

13.03 |

36.72 |

73.78 |

26.22 |

| JS-2020 |

143246 |

13.27 |

36.88 |

13.10 |

36.74 |

73.62 |

26.38 |

| SC |

142825 |

13.26 |

36.93 |

13.13 |

36.68 |

73.61 |

26.39 |

| Ea |

142334 |

13.28 |

36.89 |

13.12 |

36.72 |

73.60 |

26.40 |

| LA |

141428 |

13.28 |

36.97 |

13.06 |

36.69 |

73.66 |

26.34 |

| Fa |

141930 |

13.25 |

36.89 |

13.06 |

36.80 |

73.70 |

26.30 |

| MY-1 |

143277 |

13.28 |

36.83 |

13.14 |

36.75 |

73.58 |

26.42 |

| Kolchis |

141542 |

13.23 |

37.11 |

13.08 |

36.58 |

73.69 |

26.31 |

| Bartha |

137764 |

13.19 |

36.98 |

13.10 |

36.73 |

73.71 |

26.29 |

| Kaplan |

140377 |

13.22 |

37.05 |

13.10 |

36.63 |

73.68 |

26.32 |

| Becker |

141113 |

13.15 |

37.00 |

13.11 |

36.74 |

73.74 |

26.26 |

| NIA3 |

142228 |

13.15 |

36.97 |

13.11 |

36.77 |

73.74 |

26.26 |

Table 3.

Comparison of complete genome and gB, gC, gD, and gE genes sequences of the PRV strains.

Table 3.

Comparison of complete genome and gB, gC, gD, and gE genes sequences of the PRV strains.

Comparison with

the PRV GS-2021 Strain |

Nucleotide Sequence (%) |

| Genome Sequence |

gB |

gC |

gD |

gE |

| Chinese variant PRV strains |

99.59-99.96 |

99.90-100.00 |

99.90-100.00 |

99.80-100.00 |

99.70-99.90 |

| Chinese classical PRV strains |

98.40-99.48 |

99.30-99.80 |

96.90-99.70 |

99.50-99.70 |

99.70 |

| Foreign classical PRV strains |

96.02-97.31 |

98.40-98.50 |

94.90-96.30 |

98.90-99.30 |

97.70-98.0 |

Table 5.

The LD50 values of the PRV strains in BALB/c mice.

Table 5.

The LD50 values of the PRV strains in BALB/c mice.

| Group |

Mice number

in each group |

Dose (PFU) |

Mortality |

LD50 |

| GS-2021 |

8 |

104

|

8/8 |

102.125/0.01ul |

| 8 |

103

|

8/8 |

|

| 8 |

102

|

3/8 |

|

| Bartha-K61 |

8 |

106

|

5/8 |

105.75/0.01ul |

| 8 |

105

|

1/8 |

|

| |

8 |

104

|

0/8 |

|

| DMEM |

8 |

/ |

0/8 |

/ |